Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 April 2017

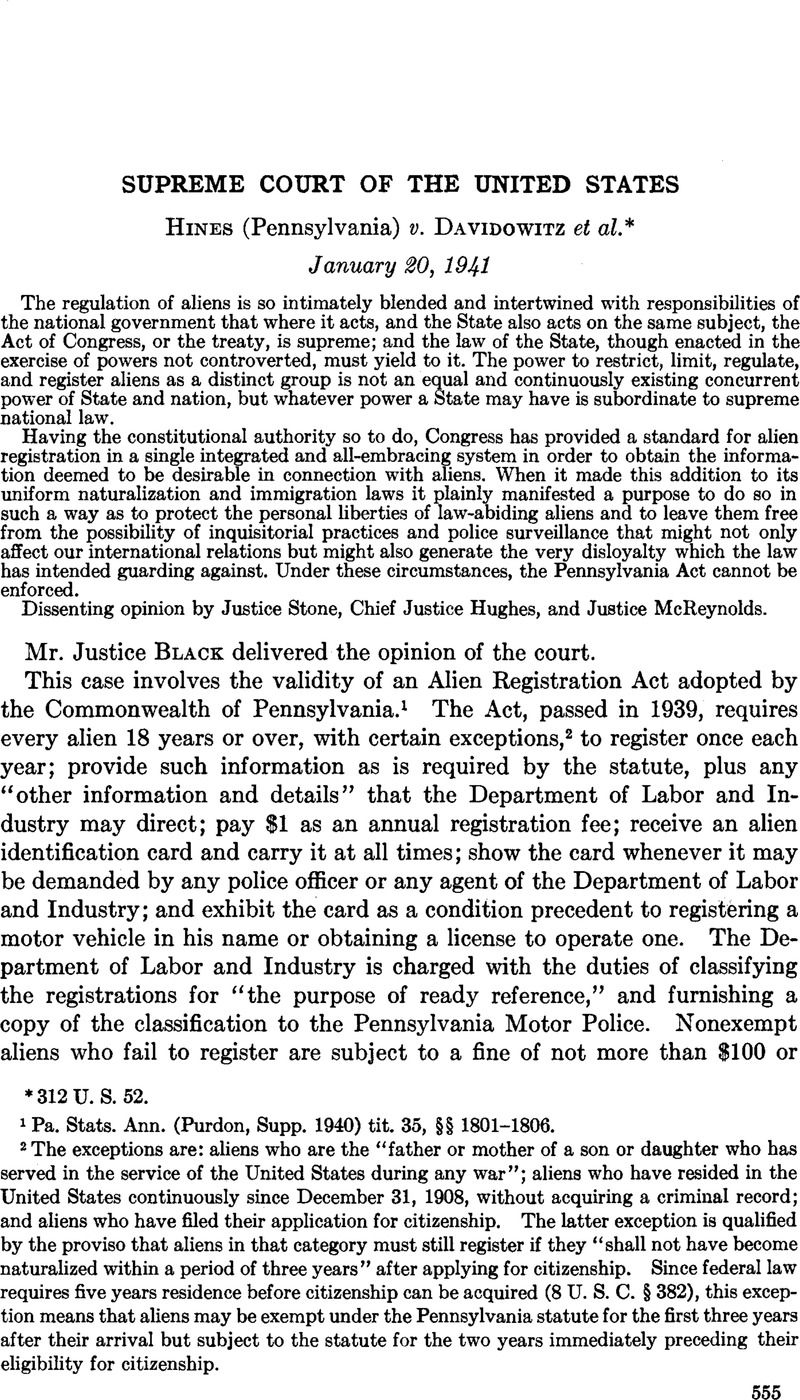

312 U. S. 52.

1 Pa. Stats. Ann. (Purdon, Supp. 1940) cit. 35, §§ 1801–1806.

2 The exceptions are: aliens who are the “father or mother of a son or daughter who has served in the service of the United States during any war”; aliens who have resided in the United States continuously since December 31, 1908, without acquiring a criminal record; and aliens who have filed their application for citizenship. The latter exception is qualified by the proviso that aliens in that category must still register if they “shall not have become naturalized within a period of three years” after applying for citizenship. Since federal law requires five years residence before citizenship can be acquired (8 U. S. C. § 382), this exception means that aliens may be exempt under the Pennsylvania statute for the first three years after their arrival but subject to the statute for the two years immediately preceding their eligibility for citizenship.

3 30 F. Supp. 470. One alien and one naturalized citizen joined in proceedings filed against certain state officials to enjoin enforcement of the Act. The answer of the defendants admitted the material allegations of the petition and defended the Act on the ground that it was within the power of the State. Plaintiffs moved for judgment on the pleadings under Rule 12 (c). The requested relief was denied as to the naturalized citizen but granted as to the alien.

4 The case is here on appeal under Section 266 of the Judicial Code, as amended (28 U. S. C. § 380). We noted probable jurisdiction on March 25, 1940.

5 Public Act No. 670, 76th Cong., 3d Sess., c. 439.

6 Cf. Vandenbark v. Owens-Illinois Glass Co., No. 141 this term, decided January 6, 1941. And see United States v. Schooner Peggy, 1 Cranch 103, 110, and Carpenter v. Wabash Ry., 309 U. S. 23, 26-27.

7 16 Stat. 140, 144, 8 U. S. C. § 41: “All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall have the same right in every State and Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons and property as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions of every kind, and to no other.”

8 Pennsylvania is not alone among the States in attempting to compel alien registration. Several States still have dormant on their statute books laws passed in 1917–18, empowering the governor to require registration when a state of war exists or when public necessity requires such a step. E. g., Conn. Gen. Stats. (1930) cit. 59, § 6042; Fla. Comp. Gen. Laws (1927) § 2078; Iowa Code (1939) § 503; La. Gen. Stats. (Dart, 1939) cit. 3, § 282; Me. Rev. Stats. (1930) Ch. 34, §3; N. H. Pub. Laws (1926) Ch. 154; N. Y. Cons. Laws (Executive Law) § 10. Other states, like Pennsylvania, have passed registration laws more recently. E. g., S. C. Acts (1940) No. 1014, § 9, p. 1939; N. C. Code (1939) §§ 193 (a)–(h). In several States, municipalities have recently undertaken local alien registration.

Registration statutes of Michigan and California were held unconstitutional in Arrowsmith v. Voorhies, 55 F. (2d) 310, and Ex parte Ah Cue, 101 Cal. 197, 35 Pac. 556.

9 The importance of national power in all matters relating to foreign affairs and the inherent danger of state action in this field are clearly developed in Federalist papers No. 3, 4, 5, 42 and 80.

10 E. g., Henderson v. Mayor of New York, 92 U. S. 259; People v. Compagnie Generale Transatlantique, 107 U. S. 59; Fong Yue Ting v. United States, 149 U. S. 698, 711. Cf. Z. & F. Assets Realization Corp. v. Hull, No. 381 this term, decided January 6, 1941.

11 The Chinese Exclusion Cases, 130 U. S. 581, 606. Thomas Jefferson, who was not generally favorable to broad federal powers, expressed a similar view in 1787: “ My own general idea was, that the States should severally preserve their sovereignty in whatever concerns themselves alone, and that whatever may concern another State, or any foreign nation, should be made a part of the federal sovereignty.” Memoir, Correspondence and Miscellanies from the Papers of Thomas Jefferson (1829), Vol. 2, p. 230, letter to Mr. Wythe. Cf. James Madison in Federalist paper No. 42: “The second class of powers, lodged in the general government, consist of those which regulate the intercourse with foreign nations. . . . This class of powers forms an obvious and essential branch of the federal administration. If we are to be one nation in any respect, it clearly ought to be in respect to other nations.”

12 Chy Lung v. Freeman, 92 U. S. 275, 279. Cf. Alexander Hamilton in Federalist paper No. 80: “The peace of the whole ought not to be left at the disposal of a part. The Union will undoubtedly be answerable to foreign powers for the conduct of its members.” That the Congress was not unaware of the possible international repercussions of registration legislation is apparent from a study of the history of the 1940 federal Act. Congressman Coffee, speaking against an earlier version of the bill, said: “Are we not guilty of deliberately insulting nations with whom we maintain friendly diplomatic relations? Are we not humiliating their nationals? Are we not violating the traditions and experiences of a century and a half?” 84 Cong. Rec. 9536.

13 For a collection of typical international controversies that have arisen in this manner, see Dunn, The Protection of Nationals (1932), p. 13 et seq. Cf. John Jay in Federalist paper No. 3: “The number of wars which have happened or will happen in the world will always be found to be in proportion to the number and weight of the causes, whether real or pretended, which provoke or invite them. If this remark be just, it becomes useful to inquire whether so many just causes of war are likely to be given by United America as by disunited America; for if it should turn out that United America will probably give the fewest, then it will follow that in this respect the Union tends most to preserve the people in a state of peace with other nations.”

14 “In consequence of the right of protection over its subjects abroad which every state enjoys, and the corresponding duty of every state to treat aliens on its territory with a certain consideration, an alien . . . must be afforded protection for his person and property. . . . Every state is by the law of nations compelled to grant to aliens at least equality before the law with its citizens, as far as safety of person and property is concerned. An alien must in particular not be wronged in person or property by the officials and courts of a state. Thus the police must not arrest him without just cause. . . . “1 Oppenheim, International Law (5th ed., 1937), pp. 547–548. And see 4 Moore, International Law Digest, pp. 2, 27, 28; Borchard, The Diplomatic Protection of Citizens Abroad (1928), pp. 25, 37, 73, 104.

15 Todok v. Union State Bank, 281 U. S. 449, 454–455.

16 Henderson v. Mayor of New York, 92 U. S. 259, 273.

17 Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 Wheat. 1, 211; see Charleston and Western Carolina Railway Co. v. Varnville Furniture Co., 237 U. S. 597. Cf. People v. Compagnie Générale Transatlantique, 107 U. S. 59, 63, where the court, speaking of a state law and a federal law dealing with the same type of control over aliens, said that the federal law “covers the same ground as the New York statute, and they cannot co-exist.”

18 Cf. Nielsen v. Johnson, 279 U. S. 47; Asakura v. Seattle, 265 U. S. 332; International Shoe Co. v. Pinkus, 278 U. S. 261, 265, and cases there cited. And see Savage v. Jones, 225 U. S. 501, 539. Appellant relies on Gilbert v. Minnesota, 254 U. S. 325, and Halter v. Nebraska, 205 U. S. 34, but neither of those cases is relevant to the issues here presented.

19 E. g., Hauenstein v. Lynham, 100 U. S. 483, 489; Geofroy v. Riggs, 133 U. S. 258, 267; Asakura v. Seattle, 265 U. S. 332, 340, 342; Nielsen v. Johnson, 279 U. S. 47, 52; Todok v. Union State Bank, 281 U. S. 449, 454; Santovincenzo v. Egan, 284 U. S. 30, 40; United States v. Belmont, 301 U. S. 324, 331 (but compare the affirmance by an equally divided court in United States v. Moscow Fire Ins. Co., 309 U. S. 624); Kelly v. Washington, 302 U. S. 1, 10, 11; Maurer v. Hamilton, 309 U. S. 598, 604; Bacardi Corporation v. Domenech, No. 21 this term, decided December 9, 1940, 85 L. Ed. 179, 183, 188.

20 Cf. Savage v. Jones, 225 U. S. 501, 553: “For when the question is whether a federal act overrides a State law, the entire scheme of the statute must of course be considered and that which needs must be implied is of no less force than that which is expressed. If the purpose of the act cannot otherwise be accomplished—if its operation within its chosen field else must be frustrated and its provisions be refused their natural effect—the state law must yield to the regulation of Congress within the sphere of its delegated power.”

21 Express recognition of the breadth of the concurrent taxing powers of state and nation is found in Federalist paper No. 32.

22 It is true that where the Constitution does not of itself prohibit state action, as in matters related to interstate commerce, and where the Congress, while regulating related matters, has purposely left untouched a distinctive part of a subject which is peculiarly adapted to local regulation, the State may legislate concerning such local matters which Congress could have covered but did not. Kelly v. Washington, 302 U. S. 1, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 (inspection for seaworthiness of hull and machinery of motor-driven tugs). And see Eeid v. Colorado, 187 U. S. 137,147 (prohibition on introduction of diseased cattle or horses); Savage v. Jones, 225 U. S. 501, 529, 532 (requirement that certain labels reveal package contents); Carey v. South Dakota, 250 U. S. 118, 121 (prohibition of shipment by carrier of wild ducks); Dickson v. Uhlmann Grain Co., 288 U. S. 188, 199 (prohibition of margin transactions in grain where there is no intent to deliver); Mintz v. Baldwin, 289 U. S. 346, 350-352 (inspection of cattle for infectious diseases); Maurer v. Hamilton, 309 U. S. 598, 604, 614 (prohibition of car-over-cab trucking).

23 As supporting the contention that the State can enforce its alien registration legislation, even though Congress has acted on the identical subject, appellant relies upon a number of previous opinions of this court. Ohio ex rel. Clarke v. Deckebach, 274 U. S. 392, 395, 396; Frick v. Webb, 263 U. S. 326, 333; Webb v. O’Brien, 263 U. S. 313, 321, 322; Terrace v. Thompson, 263 U. S. 197, 223, 224; Heim v. McCall, 239 U. S. 175, 193, 194. In each of those cases this court sustained state legislation which applied to aliens only, against an attack on the ground that the laws violated the equal protection clause of the Constitution. In each case, however, the court was careful to point out that the state law was not in violation of any valid treaties adopted by the United States, and in no instance did it appear that Congress had passed legislation on the subject. In the only case of this type in which there was an outstanding treaty provision in conflict with the state law, this court held the state law invalid. Asakura v. Seattle, 265 U. S. 332.

24 Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 369.

25 8 U. S. C. § § 152, 373, 377 (c), 382, 398, 399 (a).

26 Cf. Prigg v. Pennsylvania, 16 Pet. 539, 622, 623.

27 As early as 1641, in the Massachusetts “Body of Liberties,” we find the statement that “Every person within this Jurisdiction, whether Inhabitant or forreiner, shall enjoy the same justice and law that is generall for the plantation . . .”

28 1 Stat. 570, 577.

29 See Field, J., dissenting in Fong Yue Ting v. United States, 149 U. S. 698, 746–750 Cf. 84 Cong. Rec. 9534.

30 Quoted in Fong Yue Ting v. United States, supra, 743.

31 E.g., H. R. 9101 and H. R. 9147, 71st Cong., 2d Sess.; see 72 Cong. Rec. 3886.

32 The requirement that cards be carried and exhibited has always been regarded as one of the most objectionable features of proposed registration systems, for it is thought to be a feature that best lends itself to tyranny and intimidation. Congressman Celler, speaking in 1928 of the repeated defeat of registration bills and of an attempt by the Secretary of Labor to require registration of incoming aliens by executive order, said: “But here is the real vice of the situation and the core of the difficulty: ‘The admitted alien,’ as the order states, ‘should be cautioned to present [his card] for inspection if and when subsequently requested so to do by an officer of the Immigration Service.’ ” 70 Cong. Rec. 190.

33 Congressman Smith, who introduced the original of the bill that as finally adopted became the 1940 Act, said in committee: “The drafting of the bill is . . . a codification of measures that have been offered from time to time. . . . I have tried to eliminate from the bills that have been offered on the subject those which seemed to me would cause much controversy.” Hearings before Subcommittee No. 3 of the House Judiciary Committee, H. R. 5138, April 12, 1939, p. 71.

34 Cong. Rec, June 15, 1940, p. 12620. Senator Connally made this statement in explaining why it had been found necessary to substitute a new bill for the bill originally sent to the Senate by the House. In detailing the care that had been taken in the drafting of the new measure, he said: “We regretted very much that we had to discard entirely the bill passed by the House and substitute a new bill after the enacting clause. However, we called in Mr. Murphy, of the Drafting Service, who worked with us some 2 weeks every day. . . . We called on the Department of Justice, and had the Solicitor General with us. We called in the Commissioner of Immigration and Naturalization, and together we went over all the existing laws, and worked the new provisions into the existing laws, so as to make a harmonious whole.” This Senate version was substantially the Act as finally adopted; the alien registration provisions are Title III of a broader Act dealing with deportable offenses and advocacy of disloyalty in the armed forces.

35 In Federalist paper No. 42, the reasons for giving this power to the Federal Government are thus explained: “By the laws of several States, certain descriptions of aliens, who had rendered themselves obnoxious, were laid under interdicts inconsistent not only with the rights of citizenship but with the privilege of residence. What would have been the consequence, if such persons, by residence or otherwise, had acquired the character of citizens under the laws of another State. . . . ? Whatever the legal consequences might have been, other consequences would probably have resulted of too serious a nature not to be provided against. The new Constitution has accordingly, with great propriety, made provision against them, and all others proceeding from the defect of the Confederation on this head, by authorizing the general government to establish a uniform rule of naturalization throughout the United States.”

36 That the Congressional decision to punish only wilful transgressions was deliberate rather than inadvertent is conclusively demonstrated by the debates on the bill. E.g., Cong. Rec, June 15, 1940, p. 12621. And see note 37, infra.

37 Congressman Celler, ranking member of the House Judiciary Committee which reported out the bill, said in stating his intention of voting for the 1940 Act: “Mr. Speaker, judging the temper of the nation, I believe this compromise report is the best to be had under the circumstances and I shall vote for it. . . . Furthermore, I think the conferees have done a good job because the punishment is not too great. . . . There must be proof . . . that the alien wilfully refuses to register. . . . I drew the minority report against this bill originally, because it provided some very harsh provisions against aliens. Some of the harshness and some of the severity of the original bill have been eliminated. . . . I must admit that it is the best to be had under the circumstances.” Cong. Rec, June 22, 1940, pp. 13468–9.

1 Tit. 34 § 1311.1001, Purdon’s Perm. Stat. Ann., prohibiting hunting by aliens, was sustained in the Patsone case, 232 U. S. 138. Cf. Tit. 30 § 240. Other Pennsylvania statutes whose validity have not been passed upon regulate the activities of aliens: Tit. 63, setting forth license requirements for the practice of certain professions and occupations, make special requirements for aliens seeking to practice as certified public accountants (§ 1), architects (§ 22), engineers (§ 137), nurses (§ 202), physicians and surgeons (§ 406), and undertakers (§ 478e). The real property holdings of aliens are limited to 5000 acres of land or land producing net income of $20,000 or less (Title 69, § § 28, 32). Taxes are to be deducted from the wages of aliens by their employers when the tax collector requests (Tit. 72, § 5681).