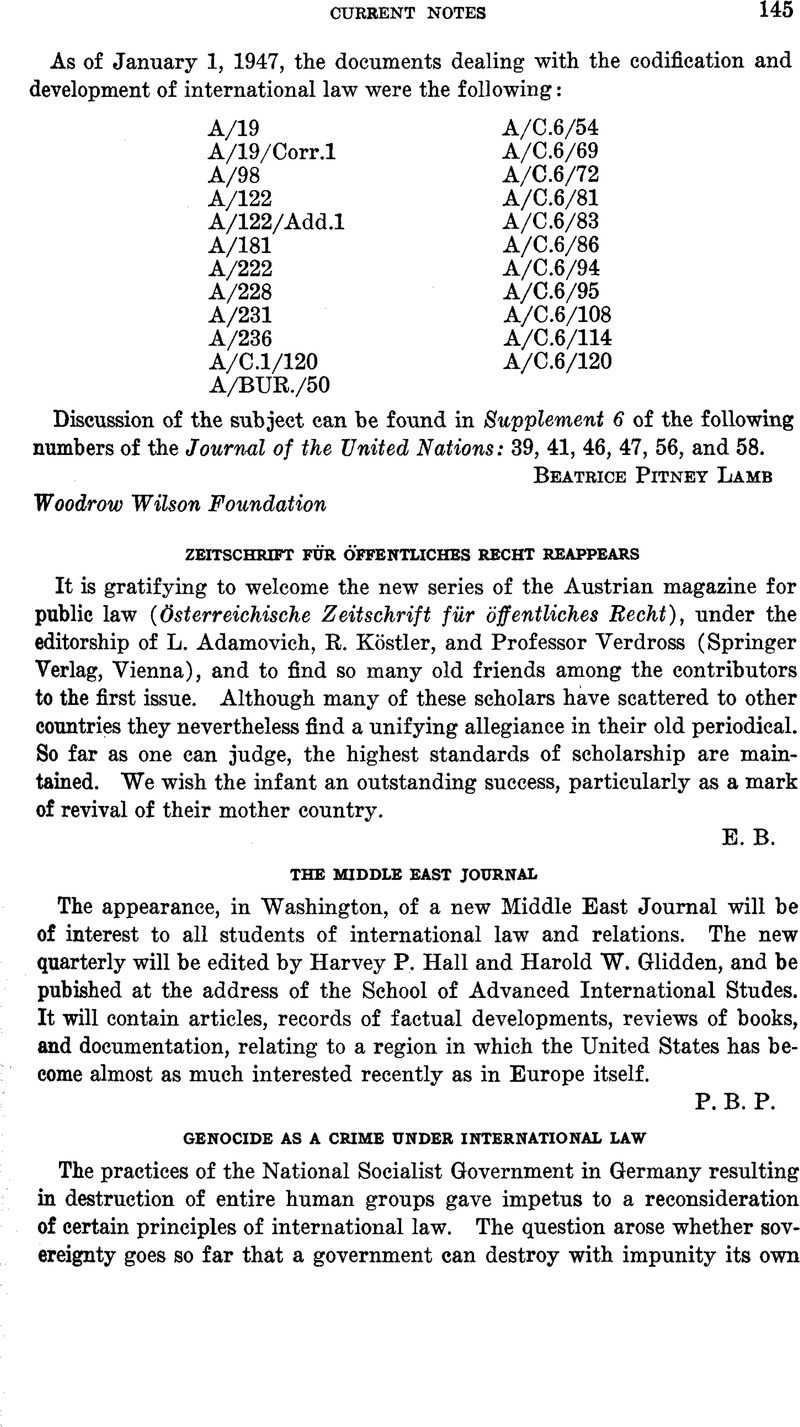

Article contents

Genocide as a Crime under International Law

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 April 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Current Notes

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1947

References

1 Although some humanitarian intervention stigmatized religious persecutions by the use of not-quite-legal terms, it has always been felt that such interventions are based essentially on considerations of international morality. Compare in this respect communication from Secretary of State Hay to Mr. “Wilson, United States Minister to Roumania, on July 17, 1902, in connection with the persecution of the Roumanian Jews: “This government cannot be a tacit party to such an international wrong” (Moore, Digest, Vol. VI, p. 364), but also instructions from Mr. Lansing to Ambassador Morgen-thau to use his good offices for the “amelioration of conditions of the Armenians, informing Turkish Government that this persecution is destroying the feeling of good will which the people of the United States have always held toward Turkey” (Foreign Relations, 1915, Supplement, p. 988).

2 See Lemkin, Baphael, Le terrorisme, in Actes de la Ve Conférence Internationale pour l’Unification du Droit pénal, Paris, Pedone, 1935 Google Scholar, and in particular by the same author the supplement to the above report entitled Les Actes Créant un danger Général (interétatique) considérés comme délits đe droit des gens: Paris, Pedone, 1933.

3 The formulation ran as follows:

Whosoever, out of hatred towards a racial, religious or social collectivty, or with a view to the extermination thereof, undertakes a punishable action against the life, bodily integrity, liberty, dignity or economic existence of a person belonging to such a collectivity, is liable, for the crime of barbarity, to a penalty of . . . unless his deed falls within a more severe provision of the given code.

Whosoever, either out of hatred towards a racial, religious or social collectivity, or with a view to the extermination thereof, destroys its cultural or artistic works, will be liable for the crime of vandalism, to a penalty of . . . unless his deed falls within a more severe provision of the given code.

The above crimes will be prosecuted and punished irrespective of the place where the crime was committed and of the nationality of the offender, according to the law of the country where the offender was apprehended.

4 Journal of the United Nations, No. 41, 1946, page 52.

5 Washington : Carnegie Endowment for International Peace ; 1944.

6 See especially statements by Sir Hartley Shawcross and Sir David Maxwell Fyfe for the British prosecution, and Champetier de Eibes and Dubost for the French prosecution, who elaborated at length and with great eloquence on the crime of genocide in the course of the Nuremberg proceedings. The concept of genocide was also used recently by the Chief of Counsel in subsequent Nuremberg proceedings, Brigadier General Telford Taylor, in the case against the Nazi doctors who experimented on human beings in concentration camps. In this classical genocide case the defendants practiced experiments in order to develop techniques for outright killings and abortions, on one hand, and sterilizations and castrations on the other hand. The writer calls the first “ktonotechnies” (from the Greek ktonos meaning murder) and the second “sterotechnics” (from the Greek steiros meaning infertile or steirosis meaning infertility). Both “ktonotechnies” and “sterotechnics” were considered by the Nazis as very essential and served the purposes of genocide in its physical and biological aspects. As to various aspects and techniques of genocide see the writer’s volume cited in note 5, above, Chapter, IX, Genocide. If and when “ sterotecnics “ achieves scientific character and is free of its genocidal purposes it could then qualify as sterology (the science of sterilization).

7 The provision of the Charter as signed by the Representatives of the United States, France, Great Britain and the Soviet Uniori on August 8, 1945, reads as follows: “Art. 6 (c) Crimes against humanity: namely, murder, extermination, enslavement, deportaron, and other inhuman acts committed against any civilian population, before or during the war; or persecution on political, racial or religious grounds in execution of or in connection with any crime within the jurisdiction of the Tribunal, whether or not in violation of domestic law of the country where perpetaated.” See United States Department of State, Executive Agreement Series, No. 17, p. 46.

8 The writer wishes to express his deep gratitude to H. E. Guillermo Belt, Ambassador of Cuba, to the Hon. Mrs. Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, Chairman of the Delegation of India, and to H. E.; Dr. Ricardo J. Alfaro, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Panama, for sponsoring the Resolution.

9 The discussions in the Legal Committee were highlighted by the very learned comments of the following: H. E. Dr. Robert Jimenez, former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Panama, Chairman of the Legal Committee of the United Nations Assembly; Mr. Charles Fahy, U. S. A.; Professor Ernesto Dihigo, Representative of Cuba; Justice Chagla, Representative of India; Dr. Jesus Maria Yepes, Legal Advisor of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Colombia; The Honorable Abdul Monim Bey Riad, Representative of Saudi-Arabia; Professor Charles Chaumont, Advisor of the French Delegation; Mr. P. N. Saptu, Alternate Representative of India; Dr. Manfred Lachs, Advisor to the delegation of Poland; Dr. Kerno, Assistant to the Secretary General of the U. N.

10 An important factor in the comparatively quick reception of the concept of genocide in international law was the understanding and support of this idea by the press of the United States and other countries. Especially remarkable contributions were made by The Washington Post (since 1944), The New York Times (since 1945), New York Herald Tribune, Dagens Nyheter in Stockholm, Sunday Times of London. The Nineteenth Century and After, London, LeMonde of Paris, Tribune des Nations in Paris, and other organs of public opinion in Switzerland, Holland, Norway, and India. Also numerous organizations working in the field of international affairs were interested and supported this concept such as The Scandinavian Institute for International Cooperation and the International Womens Alliance, both of Stockholm.

11 On responsibility of persons acting on behalf of states in the crime of genocide see article by present writer in The American Scholar, Vol. XV, No. 2 (April, 1946).

12 Text of letter in The New York Times, February 6, 1947.

13 The outline of such a treaty was offered by the writer in his article “Genocide” published in The American Scholar, as cited; it was republished in La “Revue Beige de Droit Penal et de Criminologie, Brussels, November, 1946, also in Samtiden, Oslo, October, 1946, and in a special pamphlet issued by the Secretariat D’Etat à la Présidence du Conseil et à L’Information in Paris, on September 24, 1946 (Notes Documentaires et Etudes, No. 417) under the title of Le Crime de Génocide.

14 See Memorandum sur la nécessité d’inclure les clauses contre le génocide dans les traités de paix published in the the Annex of the French pamphlet Le Crime de Génocide, cited above, note 13, wherein two alternative formulae of the crime of genocide proposed for peace treaties are introduced as follows: (1) “Whoever, while participating in a conspiracy to destroy a national, racial, or religious group, undertakes an attack against the life, liberty, or property of members of such groups is guilty of the crime of genocide”; (2) “Whoever, while participating in a conspiracy to destroy a national, racial, or religious group undertakes an attack against the life or bodily integrity or practices biological devices on members of such groups, is guilty of the crime of genocide.”

- 75

- Cited by