No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 November 2018

1 Edelman, M., The Political Uses of Social Problems (unpublished paper delivered May 7, 1985, as part of the Interdisciplinary Legal Studies Colloquium, School of Law, University of Wisconsin-Madison).Google Scholar

2 The concept of awarding to each spouse a share in the property accumulated during the marriage is of recent origin. In the past, nonincome-producing wives often left marriages with none of the assets acquired during the marriage. As late as 1968, in his authoritative text on domestic relations, Homer Clark saw the purpose of a property division as primarily one of sorting out who owned what, i.e., whose money had made the purchase or whether the property had been inherited by one of the parties. H. Clark, The Law of Domestic Relations 450–51 (1968). There is a paucity of information on what courts did in property division, but what we do know indicates that property division was not an important economic factor for most divorcing women. For example, in a six-month period in Ohio in 1930, there was a known property adjustment in only 1,227 of 6,586 cases (19%) and a lump-sum money payment (which might have been alimony, not property division) in only 691 cases (10%). L.C. Marshall & G. May, 2 The Divorce Court 328 (1933). In Kansas, where information on property settlements was published by the Kansas Judicial Council in 1942 and 1943, property division occurred in only 10% of the cases. Hopson, The Economics of Divorce: A Pilot Empirical Study at the Trial Court Level, 11 Kan. L. Rev. 107, 109 (1962). Alimony has always been available to the “innocent” party on divorce, but it has not been awarded in most cases. Weitzman reports at 180, 181: Although the available historical evidence is limited, … [t]here is no evidence that alimony has ever been awarded in more than a relatively small minority of divorces. The U.S. Census Bureau collected national data on alimony awards between 1887 and 1922 and found thai only 9.3 percent of divorces between 1887 and 1906 included provisions for permanent alimony, as did 15.4 percent of those in 1916, and 14.6 percent of those in 1922 [citing Jacobson, American Marriage and Divorce 126 (1959)]. The limited historical data from single states point to the same conclusion: alimony was awarded in 31 percent of the divorce cases in Los Angeles in 1919 [citing May, Pursuit of Domestic Perfection 177 (1975)], in 6.6 percent of 3,000 Maryland cases in 1929; and in 16.5 percent of 6,800 Ohio cases in 1930 [citing, Foote, Levy & Sander, Cases and Materials on Family Law (1st ed 1966)].Google Scholar

3 Problems with child support can be traced back at least to the early part of this century when they had become sufficiently acute to attract the attention of the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws. In 1907 that body directed its Committee on Marriage and Divorce to study the problem. In 1908 the committee reported to the commissioners that William H. Baldwin had gathered statistics indicating that family desertion was on the rise and that it was “due to moral rather than to physical causes.” Baldwin found that “the usual deserter is not a man who is physically weak or ill and discouraged, nor desperate because of bad housekeeping or his wife's ill temper; he is a young, able-bodied man, who leaves because he is well able to take care of himself and desires to indulge a selfish or vicious impulse, or to avoid ordinary cares or some unusual trouble.” The committee concluded from these findings that family desertion should be treated as a crime and proposed a Uniform Desertion and Nonsupport Act incorporating 14 provisions suggested by Baldwin. The law provided, e.g., that desertion and nonsupport were extraditable offenses, that the law also applied to a mother who deserted or neglected children dependent on her for support, and that a wife was a competent witness, obliged to testify against her husband. It was approved in 1910. However, the act proved to be ineffective; on the one hand, it was too drastic because it provided no civil remedies, only criminal prosecution; on the other, it was inadequate because it provided no interstate enforcement procedures for an increasingly mobile population. By 1944 the problem of interstate enforcement had reached such proportions that the commissioners began studying the problem again. In 1950, they proposed the Uniform Reciprocal Enforcement of Support Act which was amended in 1952 and 1958 and revised in 1968. It has been adopted in one of these forms by all American jurisdictions. See 9A Uniform Laws Ann. (1986 Supp.). In the late 1940s Congress began to be concerned about the expenditures of funds under the Aid to Families of Dependent Children (AFDC) program. AFDC is the public assistance program established by the Social Security Act in 1935 as a joint state-federal effort to provide a minimal standard of living for children who had lost their primary supporting parent through death. The drafters of the Social Security Act had not envisioned the program as a measure to shore up the inadequacies of a divorce system that failed to provide adequately for children, but by 1949 the Social Security Administration estimated that the total bill for aid to families where the father was absent and not supporting was about 205 million.Google Scholar

4 The transformation of a social condition into a social problem is a complex process, as Edelman points out. In the case of the post-divorce poverty of women and children, the social problem nature of that condition has, as pointed out in note 3, also been promoted by those concerned about increases in public welfare expenditures.Google Scholar

5 All American jurisdictions provide for some form of no-fault divorce. The term describes a variety of legislative enactments that authorize the granting of a divorce without requiring proof of fault in the marital relationship by one of the parties. No-fault grounds include proof that the marriage is irretrievably broken, that the parties have irreconcilable differences, that the parties are incompatible, or that they have lived apart for a stated period of time ranging from six months to two years. In 14 states (Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Iowa, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Oregon, Washington, and Wisconsin) no fault is the only ground for divorce; in the rest of the states it is a possible ground along with fault.Google Scholar

6 It must be remembered that the change to the no-fault ground was in the statement of the theoretical basis of the law, not in the manner in which it operated in practice. Lawrence Friedman points out that beginning in 1870 the rise of consent divorce-often involving perjury-made fault grounds a sham. Friedman, Rights of Passage: Divorce Law in Perspective, 63 Ore. L. Rev. 649 (1984).Google Scholar

7 Melli, Erlanger, & Chambliss, The Process of Negotiation: An Exploratory Investigation in the Divorce Context 25 (Institute for Legal Studies, Law School, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Working paper series 7, No. 1 (Dec. 1985)).Google Scholar

8 See, e.g., the discussion in Levy, Uniform Marriage and Divorce Legislation: A Preliminary Analysis 47–49 (undated report prepared for the Special Committee of the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws); Friedman, supra note 6.Google Scholar

9 See studies cited supra note 3 and in Herbert Jacob's essay in this issue, “Faulting No-Fault,” at 773 n.2. Also, Duncan & Hoffman, A Reconsideration of the Economic Consequences of Marital Dissolution, 22 Demography 485 (1985); Chambers, supra note 3, at 42.Google Scholar

10 The most extensive study of the relationship between the grounds for divorce stated in the law and the rate of marital breakup was made by the Interprofessional Commission on Marriage and Divorce established under the sponsorship of the American Bar Association in 1946, shortly after the divorce rate in the United States had soared. The results of the work of that group were summarized in M. Rheinstein, Marriage Stability, Divorce, and the Law (1972). In that book Rheinstein traced the history of divorce laws and divorce reform efforts in the United States. He characterized the fault system existing in the United States in the 1960s as a dual system-the law on the books and the law in operation-that allowed conservatives to have strict grounds for divorce on the books and liberals to have easy and consent divorce in practice. He also surveyed the literature and reported (id. at 288–307) on statistical studies of divorce rates in both Europe and the United States, finding generally that research showed that the law has little relation to the divorce rate. Rheinstein noted: “In fact, so thoroughly are social scientists convinced of the irrelevancy of divorce laws that in recent writing the legal aspects of family breakdown are more or less neglected” (id. at 292). He did recognize one way in which the law affects the divorce rate. If the law prohibits divorce completely or is exceedingly restrictive, the divorce rate may be nonexistent or low. But factual marital breakdown, separated couples, or abandoned families without formal divorce are the result (id. at 158). For an excellent recent analysis of the nonrelation of a rising divorce rate and no-fault grounds, see Frank, Berman, & Mazur-Hart, No Fault Divorce and the Divorce Rate: The Nebraska Experience, 58 Neb. L. Rev. 1 (1978). See also McGraw, Sternin, & Davis, A Case Study in Divorce Law Reform and Its Aftermath, 20 J. Fam. Law 443 (1981–82); Pike, Legal Access and the Incidence of Divorce in Canada: A Sociohistorical Analysis, 12 Can. Rev. Soc. & Anthropology 115, 126 (1975); Schoen, Greenblatt, & Mielke, California's Experience with Non-Adversary Divorce, 12 Demography 223 (1975). For another view, see Stetson & Wright, The Effects of Laws on Divorce in American States, 75 J. Marriage & Fam. 537 (1975).Google Scholar

11 See supra note 5.Google Scholar

12 Arkansas, Connecticut, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, and West Virginia are all listed by Family Law Reporter as having separation as no-fault grounds for divorce, 12 Fam. L. Rep. 400:1 (3–24-86).Google Scholar

13 See Jacobs, H., supra note 9.Google Scholar

14 Melli, Erlanger, & Chamblis, supra note 7.Google Scholar

15 See Weitzman at 343, especially nn.20-23.Google Scholar

16 Historically women have been interested in relaxing the strict requirements for divorce that often favored men. See, e.g., W.L. O'Neill, Divorce in the Progressive Era (1967); C. Deglar, At Odds: Women and Family in America from the Revolution to the Present (1980).Google Scholar

17 Insofar as there are differences, men were less positive about their post-divorce situation: 82% felt better about themselves, 47% considered themselves more competent in their work, 45% considered themselves more attractive, and 48% felt they possessed better parenting skills. Weitzman at 346.Google Scholar

18 The number of entries in the Index to Legal Periodicals dealing with the division of assets on divorce has mushroomed in the past decade. There are books and periodicals devoted to the subject. See, e.g., B.H. Goldberg, Valuation of Divorce Assets (1984); L.J. Golden, Equitable Distribution of Property (1983); Fair Share (monthly newsletter).Google Scholar

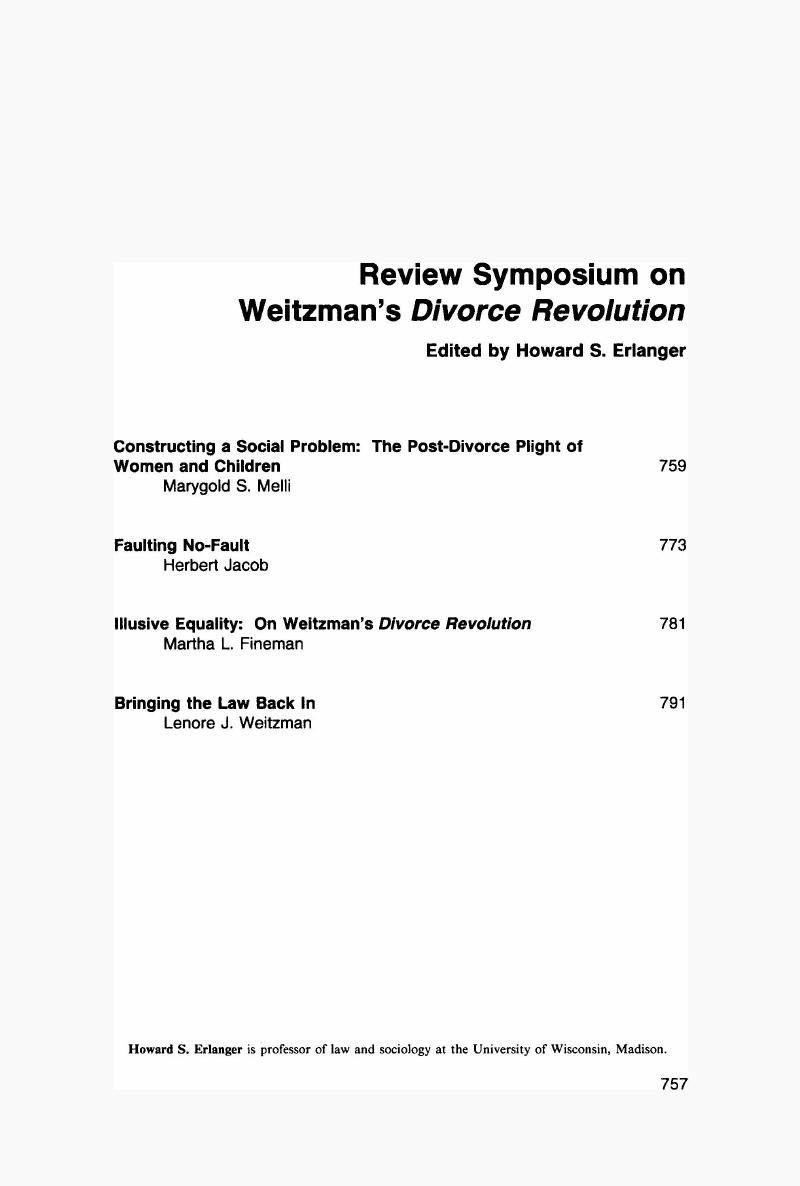

19 Freed & Walker, Family Law in the Fifty States: An Overview, 4 Fam. L.Q. 369 (1985).Google Scholar

20 Fineman, Martha L., Illusive Equality: On Weitzman's Divorce Revolution, 1986 A.B.F. Res. J.Google Scholar