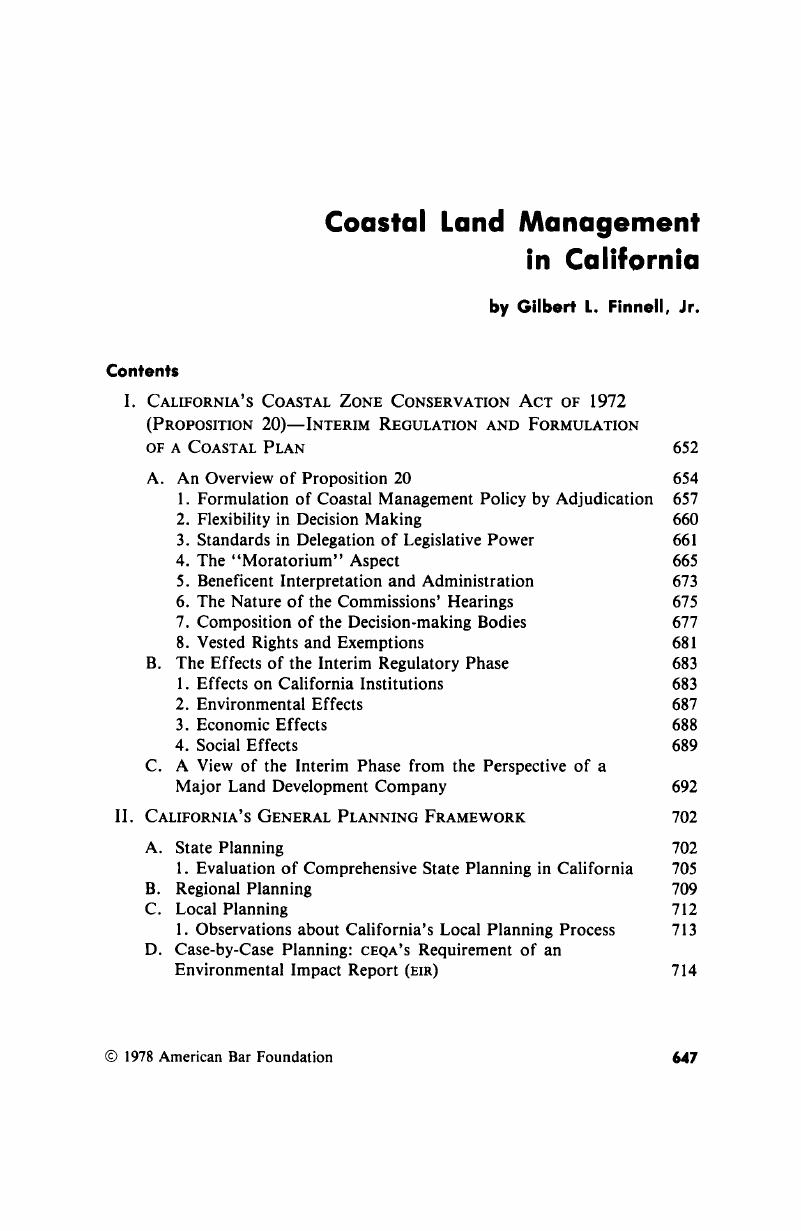

Article contents

Coastal Land Management in California

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 November 2018

Abstract

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Bar Foundation, 1978

References

1. “In the past 30 years, California’s population has tripled to more than 20 million; 85 percent of this population lives within 30 miles of the coast, and 64 percent within the 15 coastal counties.” California Coastal Zone Conservation Commissions, California Coastal Plan 79 (Sacramento, Cal.: Documents and Publications Branch, 1975) [hereinafter cited as 1975 Coastal Plan).Google Scholar

2. California Coastal Act of 1976, Cai. Pub. Res. Code §§ 30000-30900 (West 1977 & Cum. Supp. 1978) [hereinafter cited as 1976 cca].Google Scholar

3. California Coastal Zone Conservation Act of 1972, 1972 Cal. Stats. A-181 (repealed on Jan. 1, 1977) [hereinafter cited as 1972 cczca].Google Scholar

4. See Beuscher, Jacob H., Wright, Robert R., & Gitelman, Morton, Cases and Materials on Land Use 501 (2d ed. St. Paul: West Publishing Co., 1976).Google Scholar

5. Id. Google Scholar

6. 272 U.S. 365 (1926). Compare Nectow v. City of Cambridge, 277 U.S. 183 (1928) (specific due process attack).Google Scholar

7. See, e.g., Babcock, Richard F., The Zoning Game: Municipal Practices and Policies (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1966).Google Scholar

8. Cf. U.S., Council on Environmental Quality, Fifth Annual Report 51-54 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1974), discussed in Beuscher et al., supra note 4, at 504-6.Google Scholar

9. See, e.g., Bosselman, Fred & Callies, David, for the Council on Environmental Quality, The Quiet Revolution in Land Use Control (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1972).Google Scholar

10. See Florida Environmental Land and Water Management Act of 1972, Fla. Stat. Ann. ch. 380 (West 1974 & Cum. Supp. 1978); Florida State Comprehensive Planning Act of 1972, Fla. Stat. Ann. ch. 23, pt. 1 (West Cum. Supp. 1978); Land Conservation Act of 1972, Fla. Stat. Ann. ch. 259 (West 1974) (proposed by the Governor’s Task Force on Resource Management). See also Florida Water Resources Act of 1972, Fla. Stat. Ann. ch. 373, pt. 1 (West 1974 & Cum. Supp. 1978) (proposed by the House Interim Study Committee on Water Resource Management and supported by the task force). This legislation “constitutes one of the most significant advances in state land use legislation in this country’s history—certainly comparable with the 1970 Vermont legislation and the earlier Hawaii legislation.” Address by Fred P. Bosselman, American Society of Planning Officials National Planning Conference, Apr. 17, 1972.Google Scholar

11. See generally 1 Williams, Norman Jr., American Planning Law: Land Use and the Police Power §§ 7.04-.05, at 179-84 (Chicago: Callaghan & Co., 1974).Google Scholar

12. See generally for citations to the extensive literature on “home rule,” Sho Sato, “Municipal Affairs” in California, 60 Calif. L. Rev. 1055 n.l (1972).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

13. Cf. ceeed v. California Coastal Zone Conservation Comm’n, 43 Cal. App. 3d 306, 118 Cal. Rptr. 315 (1974).Google Scholar

14. Fla. Stat. Ann. ch. 380 (West 1974 & Cum. Supp. 1978). See Cross Key Waterways v. Askew, 351 So. 2d 1062 (Fla. 1st Dist. Ct. App. 1977) (holding, inter alia, that the “Florida Constitution does not forbid State reclamation of regulatory power from local government and its reassignment to State agencies,” id. at 1065). See generally Charles L. Keesey, Florida Home Rule Powers, prepared for the Florida Environmental Land Management Study Committee (Sept. 10, 1973) (Legislative Research Library, Tallahassee).Google Scholar

15. See Robert Kratovil & John T. Ziegweid, Illinois Municipal Home Rule and Urban Land—a Test of the New Constitution, 22 DePaul L. Rev. 359, 366-67 (1972) (discussion of distinction between “state affairs” and “municipal affairs”).Google Scholar

16. Id. (citing Straw v. Harris, 54 Or. 424, 103 P. 777 (1909), and as contra, 16 Wyo. L.J. 47, 51 (1961)).Google Scholar

17. Interview with Michael Fischer, executive director, North Central Coast Regional Commission, in San Rafael, Cal., Feb. 11, 1975.Google Scholar

18. See Fred C. Doolittle, Land-Use Planning and Regulation on the California Coast: The State Role, University of California, Institute of Governmental Affairs, Environmental Quality Series no. 9 (Davis, Cal., 1972).Google Scholar

19. See generally, for the history of Proposition 20, Anderson, Janell, Economic Regulation and Development Goals: The California Coastal Initiative (Davis: University of California, Institute of Governmental Affairs, 1974); Philip L. Fradkin, California: The Golden Coast (New York: Viking Press, 1974); Robert G. Healy, Land Use and the States (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, for Resources for the Future, 1976); Melvin Mogulof, Saving the Coast: California’s Experiment in Intergovernmental Land Use Regulation (Lexington: Lexington Books, 1975); Stanley Scott, Governing California’s Coast (Berkeley: University of California, Institute of Governmental Studies, 1975); Janet Adams, Proposition 20—a Citizens’ Campaign, 24 Syracuse L. Rev. 1019 (1973); Peter M. Douglas, Coastal Zone Management—a New Approach in California, 1 Coastal Zone Management J. 1 (1973); Peter M. Douglas & Joseph E. Petrillo, California’s Coast: The Struggle Today—a Plan for Tomorrow, Pt. I, 4 Fia. St. U.L. Rev. 177 (1976), Pt. II at id. 315; Neil E. Franklin, Patricia S. Peterson, & William Walker, Saving the Coast: The California Coastal Zone Conservation Act of 1972, 4 Golden Gate L. Rev. 307 (1974); Robert G. Healy, Saving California’s Coast: The Coastal Zone Initiative and Its Aftermath, 1 Coastal Zone Management J. 365 (1974); John M. Winters, Environmentally Sensitive Land Use Regulation in California, 10 San Diego L. Rev. 693 (1973); Statutory Comment, Coastal Controls in California: Wave of the Future? 11 Harv. J. Legis. 463 (1974); Note, Saving the Seashore: Management Planning for the Coastal Zone, 25 Hastings L.J. 191 (1973); Note, A Decision-Making Process for the California Coastal Zone, 46 S. Cal. L. Rev. 513 (1973).Google Scholar

20. Report of Joint Legislative Committee on Sea Coast Conservation, Cal. Assembly J., 48th Sess. 461-62 (1931). See generally Adams, supra note 19, at 1019-22.Google Scholar

21. Adams, supra note 19, at 1021.Google Scholar

22. California, Department of Navigation and Ocean Development, California Comprehensive Ocean Area Plan [coap], at 1-2 [1972].Google Scholar

23. This report is intended to serve as a foundation for setting the State’s policy in the management of California’s coastal zone. It is based on a comprehensive inventory of our coastal resources and broadly based consultation and research. It proposes guidelines for the wise utilization of these resources which would be applicable to whatever management system is established to implement State policy. It identifies principal conflicts of use, discusses important issues, and proposes basic guidance for achieving a proper, reasonable and equitable balance between conservation and development which would be in the net public interest.Google Scholar

Id. at iii. See also appendices to coap, e.g., appendix II, Gruen Gruen & Associates & Sed- way/Cooke, Approaches Towards a Land Use Allocation System for California’s Coastal Zone: Report to the Department of Navigation & Ocean Development of the Resources Agency, State of California ([San Francisco] 1971). coap was favorably evaluated by Robert B. Krueger, Esq., formerly chairman, California Advisory Commission on Marine and Coastal Resources, in an interview in Los Angeles, Feb. 18, 1975. Several other knowledgeable persons, however, expressed some doubt of coap‘s value to the Proposition 20 planning effort.Google Scholar

24. See Adams, supra note 19, at 1029-32. A.B. 2090, a seminal bill introduced by Assemblyman Alan Sieroty in Apr. 1969 “would have been the first step in establishing a Southern California regional agency.” Doolittle, supra note 18, at 39.Google Scholar

25. Cal. Const, art. IV, § 1. See Max Radin, Popular Legislation in California: 1936-1946, 35 Calif. L. Rev. 171 (1947); Comment, The Scope of the Initiative Referendum in California. 54 Calif. L. Rev. 1717 (1966).Google Scholar

26. Cal. Const, art. 2, § 10 (Supp. 1955-77).Google Scholar

27. The widely publicized tax limitation, approved by the people June 6, 1978, adding art. 13A, §§ 1-6, to the California constitution. See West’s Cal. Legis. Serv. 1978, no. 4, at xxv-xxvi.Google Scholar

28. See Adams, supra note 19, at 1027.Google Scholar

29. See the requirements in Cal. Const, art. 2, § 8 (Supp. 1955-77).Google Scholar

30. Adams, supra note 19, at 1036.Google Scholar

31. See generally id. at 1036-42; interview with Donald D. Gralnek, Esq., in San Francisco, May 23, 1975.Google Scholar

32. 1972 cczcA, supra note 3, ch. 8, § 5.Google Scholar

33. See Adams, supra note 19, at 1042.Google Scholar

34. 1972 cczca, supra note 3, §§ 27000(a), (b), 27300 el seq. Google Scholar

35. Id. §§ 27001(c), 27400 et seq. Google Scholar

36. Id. § 27400.Google Scholar

37. Id. § 27650. Amended by 1974 Stats. ch. 897, § 2 (original initiative providing termination as “the 91st day after the final adjournment of the 1976 Regular Session of the Legislature”).Google Scholar

38. 1976 cca, supra note 2, § 30600(c) (1977).Google Scholar

39. See notes 371-91 infra and text at same.Google Scholar

40. 1972 cczcA, supra note 3, § 27001(c).Google Scholar

41. See notes 103-17 infra and text at same.Google Scholar

42. This is a strong impression I gained from all interviews. No one suggested otherwise.Google Scholar

43. CEEED v. California Coastal Zone Conservation Comm’n, 43 Cal. App. 3d 306, 118 Cal. Rptr. 315 (4th Dist. Ct. App. 1974). See notes 60-61 infra and text at same.Google Scholar

44. See Davis, Kenneth Culp, Administrative Law Text § 6.03, at 142 (3d ed. St. Paul: West Publishing Co., 1972).Google Scholar

45. Healy, Saving California’s Coast, supra note 19, at 387.Google Scholar

46. Interview with Joseph Bodovitz, executive director, California Coastal Zone Conservation Commission, in San Francisco, Feb. 10, 1975.Google Scholar

47. See, e.g., notes 97-102 infra and text at same.Google Scholar

48. Davis, supra note 44, § 4.12, at 121.Google Scholar

49. See, e.g., Scott, supra note 19, at 61-63.Google Scholar

50. Interview with Lorell Long, staff member, Energy Resources Conservation and Development Commission, in Sacramento, Aug. 26, 1975.Google Scholar

51. 1972 cczcA, supra note 3, § 27402. The policy statements of § 27001 and the objectives of § 27302 were specifically referred to as additional standards.Google Scholar

52. See notes 116-17 infra and text at same for scope of judicial review. See also Davis, supra note 44, §§ 29.01-.02, at 525-30, for discussion of the “substantial evidence rule.” (“Under this rule, the court decides questions of law but it limits itself to the test of reasonableness in reviewing findings of fact.” Id. at 525.)Google Scholar

53. 1972 cczcA, supra note 3, § 27401.Google Scholar

54. See my article, The Federal Regulatory Role in Coastal Land Management, 1978 A.B.F. Research J. 169, at 202-4 & nn. 180-88 [hereinafter cited as The Federal Role], Two important exceptions to the United States Supreme Court’s tendency to uphold congressional delegations are A. L. A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, 295 U.S. 495 (1935), and Panama Ref. Co. v. Ryan, 293 U.S. 388 (1935). Subsequent decisions upholding broad delegations include Arizona v. California, 373 U.S. 546 (1963); Yakus v. United States, 321 U.S. 414 (1944); and Lichter v. United States, 334 U.S. 742 (1948). See generally Davis, supra note 44, § 2.00, at 40 et seq. for three cases (out of “perhaps three hundred cases”) in which Davis believes “the whole policy of the government on the particular subject was made by the agency without guidance from Congress”; Walter Gellhorn & Clark Byse, Administrative Law: Cases and Comments 71-84 (6th ed. Mineola, N.Y.: Foundation Press, 1974) (“The steady course of Supreme Court decisions since the Panama Refining and Schechter cases underscores the improbability that a federal statute regulating business practices and not affecting freedom of expression will be found defective on the ground that it violates the delegation doctrine.” Id. at 84).Google Scholar

55. 351 So. 2d 1062 (Fla. 1st Dist. Ct. App. 1977). Cross Key, which was argued before the Florida Supreme Court in Jan. 1978, upheld the Florida Environmental Land and Water Management Act of 1972, Fla. Stat. Ann. ch. 380 (West 1974 & Cum. Supp. 1978), against several attacks, but held the act’s standards for guiding the governor and cabinet in designation of certain kinds of areas of critical state concern inadequate and unconstitutional under the separation of powers section of the Florida constitution.Google Scholar

56. The Florida Supreme Court’s 7-0 decision was handed down on Nov. 22, 1978. Telephone conversation with Nancy Linnan, Esq., office of the governor, state of Florida, Chicago to Tallahassee, Nov. 22, 1978.Google Scholar

57. The nondelegation doctrine has been relaxed in many state courts. In addition to the California cases, discussed here, see, for recent state supreme court decisions that have adopted the position that procedural safeguards, including the formulation of subsidiary administrative standards, are more important than insisting on precise legislative standards: Boehl v. Sabre Jet Room, Inc., 349 P.2d 585 (Alas. 1960); Barry & Barry, Inc. v. State Dep’t of Motor Vehicles, 81 Wash. 2d 155, 500 P.2d 540 (1972), appeal dismissed, 410 U.S. 977 (1973); Watchmaking Examining Bd. v. Husar, 49 Wis. 2d 526, 182 N.W.2d 257 (1971). Notwithstanding the liberalization of the doctrine in many state courts, it has retained considerable vitality in others. See generally 1 Frank E. Cooper, Stale Administrative Law (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1965); Davis, supra note 44, at 37; Gellhorn & Byse, supra note 54, at 84; Jaffe, Louis L., Judicial Control of Administrative Action 73-85 (Abridged ed. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1965); Note, Safeguards, Standards, and Necessity: Permissible Parameters for Legislative Delegations in Iowa, 58 Iowa L. Rev. 974 (1973); Recent Developments, State Statutes Delegating Legislative Power Need Not Prescribe Standards, 14 Stan. L. Rev. 372 (1962).Google Scholar

58. See generally Davis, supra note 44, at 37. Professor Davis notes: “Legislatures, especially in closing hours of a session, are often less responsible than Congress; their draftsmen are often less skillful in clarifying legislative intent; direct responsiveness to special-interest groups is often more pronounced; committee investigations are usually less thorough; delegations to petty officers is more common; and, especially, safeguards to protect against arbitrary action are generally less developed.” Id. Google Scholar

59. Id. at 39-40.Google Scholar

60. 43 Cal. App. 3d 306, 118 Cal. Rptr. 315 (4th Dist. Ct. App. 1974).Google Scholar

61. The ceeed court also reviewed Candlestick Properties, Inc. v. San Francisco Bay Conservation & Dev. Comm’n, 11 Cal. App. 3d 557, 89 Cal. Rptr. 897 (1st Dist. Ct. App. 1970), and Friends of Mammoth v. Board of Supervisors, 8 Cal. 3d 247, 502 P.2d 1049, 104 Cal. Rptr. 761 (1972), both of which upheld delegations in similarly broad language. In 1976, the Rhode Island Supreme Court upheld, in J. M. Mills, Inc. v. Murphy, 116 R.I. 54, 352 A.2d 661 (1976), the constitutionality of Rhode Island’s Fresh Water Wetlands Act on the basis of a delegation of legislative power expressed with broad standards. The director of the Department of Natural Resources was empowered to deny an application to alter a wetland if “in the opinion of the director granting of such approval would not be in the best public interest.” The “best public interest” standard, the court concluded, was adequate especially when measured by the act’s intended purposes and policies, which the court held were relevant and should be incorporated as part of the guiding standards.Google Scholar

62. Fla. Const, art. 2, § 7.Google Scholar

63. 116 R.I. 54, 352 A.2d 661 (1976).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

64. See notes 65-68 infra and text at same.Google Scholar

65. 9 Cal. 3d 888, 513 P.2d 129, 109 Cal. Rptr. 377 (1973).Google Scholar

66. A Los Angeles attorney who represented major development and oil interests and was chairman of the California Advisory Commission on Marine and Coastal Resources bluntly estimated that “if they followed the guidelines set forth in the act they would not approve nine- tenths of what comes before them.” Krueger interview, supra note 23. Another attorney, who represented developers of two of the major Northern California projects, believed that, although the commission tended to approve many smaller proposals (particularly single-family houses), it had imposed a moratorium, in northern California, on major new developments. Interview with Howard N. Ellman, Esq., in San Francisco, May 22, 1975. Furthermore, he explained how the effects were felt even outside the permit zone because of the creation of uncertainties in the financial markets. An attorney who was closely associated with the drafters and supporters of Proposition 20 conceded that the commissions could have been much more restrictive in the projects they approved. Interview with Ronald J. Gilson, Esq., in San Francisco, Feb. 11, 1975. He believed the California courts would have upheld a virtual moratorium, but stressed that the state commission had attempted to avoid the moratorium interpretation. In contrast, however, an attorney who supported passage and implementation of Proposition 20 believed the act was not a moratorium, could not be effectively interpreted as such, and, in any event, was not so interpreted by the commission. Gralnek interview, supra note 31.Google Scholar

67. Healy, Saving California’s Coast, supra note 19, at 371.Google Scholar

68. Interview with Thomas Crandall, executive director, San Diego Coast Regional Commission, in San Diego, Feb. 20, 1975.Google Scholar

69. See generally Robert H. Freilich, Interim Development Controls: Essential Tools for Implementing Flexible Planning and Zoning, 49 J. Urban L. 65 (1971).Google Scholar

70. Professor Williams believes that predictions on the validity of interim controls can be based on the state’s general attitude toward zoning. “Thus, as would be expected, California and New Jersey have found a way to approve interim zoning, and no doubt Massachusetts and Maryland would if the occasion arose; Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania have disapproved, and so no doubt would Illinois and Rhode Island.” 1 Williams, supra note 11, § 30.02, at 602. The reporters of the ali Model Land Development Code note the favorable judicial view toward temporary land-use restrictions during the time when a plan is being prepared, ali Model Land Development Code § 7-205, at 266 (1975) [hereinafter cited as ali Code].Google Scholar

71. See The Federal Role, supra note 54, at 221-29 & nn. 290-324, for a discussion of some of the differences.Google Scholar

72. 272 U.S. 365, 395, 397 (1926).Google Scholar

73. See generally American Society of Planning Officials, Urban Growth Management Systems: An Evaluation of Policy-related Research, Planning Advisory Service Report nos. 309. 310, at 61 (Chicago: American Society of Planning Officials [1975]) [hereinafter cited as aspo] (citing Zahn v. Board of Public Works, 274 U.S. 325, 328 (1927)).Google Scholar

74. 43 Cal. App. 3d 306, 118 Cal. Rptr. 315 (4th Dist. Ct. App. 1974).Google Scholar

75. “The striking feature of California zoning law is that the courts in that state have quite consistently been far rougher on the property rights of developers than those in any other state.” 1 Williams, supra note 11, § 6.03, at 115. Miller v. Board of Public Works, 195 Cal. 477, 234 P. 381 (1925), cert, denied, 273 U.S. 781 (1927), is often cited for the validity of interim zoning during the formulation of master plans.Google Scholar

76. See ceeed, 43 Cal. App. 3d at 314, 118 Cal. Rptr. at 321, drawing attention to Cal. Gov. Code § 65858. (West 1966 & Supp. 1966-77).Google Scholar

77. See Tahoe Regional Planning Compact, Pub. L. No. 91-148, 83 Stat. 360, approved Dec. 18, 1969; Cal. Gov. Code § 66600-66661 (West 1966 & Supp. 1966-77); Bosselman & Callies, supra note 9, at 108-35, 291-93.Google Scholar

78. “[T]he reports burst with successful due process attacks on zoning laws as applied… .Yet an entire generation of law students has grown up learning that courts do (should) not undo social or economic regulation in the name of substantive due process simply because judges question a legislature’s wisdom. Is there something about zoning that gives it a special vulnerability to substantive due process assaults?” Curtis J. Berger, Land Ownership and Use 686 (2d ed. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1975). See The Federal Role, supra note 54, at 224-25 & nn. 307-15.Google Scholar

79. Nectow v. City of Cambridge, 277 U.S. 183 (1928).Google Scholar

80. Cf. ceeed, 43 Cal. App. 3d 306, 118 Cal. Rptr. 315 (4th Dist. Ct. Ap. 1974).Google Scholar

81. 277 U.S. at 188-89.Google Scholar

82. 260 U.S. 393, 415 (1922).Google Scholar

83. See, e.g., Bosselman, Fred, Callies, David, & Banta, John, The Taking Issue: An Analysis of the Constitutional Limits of Land Use Control (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1973); Philip Soper, The Constitutional Framework of Environmental Law 20, 50-71 in Erica L. Dolgin & Thomas G. P. Guilbert, eds., Federal Environmental Law (St. Paul: West Publishing Co., 1974); Arvo Van Alstyne, Statutory Modification of Inverse Condemnation: The Scope of Legislative Power, 19 Stan. L. Rev. 727 (1967); Arvo Van Alstyne, Taking or Damaging by Police Power: The Search for Inverse Condemnation Criteria, 44 S. Cal. L. Rev. 1 (1970); Frank I. Michelman, Property, Utility, and Fairness: Comments on the Ethical Foundations of “Just Compensation” Law, 80 Harv. L. Rev. 1165 (1967); Joseph L. Sax, Takings, Private Property and Public Rights, 81 Yale L.J. 149 (1971); Joseph L. Sax, Takings and the Police Power, 74 Yale L. J. 36 (1964); Allison Dunham, Griggs v. Allegheny County in Perspective: Thirty Years of Supreme Court Expropriation Law, 1962 Sup. Ct. Rev. 63; Robert Kratovil & Frank J. Harrison, Jr., Eminent Domain—Policy and Concept, 42 Calif. L. Rev. 596 (1954).Google Scholar

84. The Supreme Court’s opinion in Penn Cent. Transp. Co. v. City of New York, 98 S. Ct. 2546 (1978), upholding, as against a taking attack, New York City’s Landmarks Preservation Law as applied to Grand Central Terminal, continues to recognize the validity of the Holmes Pennsylvania Coal approach. Justice Brennan’s opinion for the Court adds: The question of what constitutes a “taking” for purposes of the Fifth Amendment has proved to be a problem of considerable difficulty… .this Court, quite simply, has been unable to develop any “set formula” for determining when “justice and fairness” require that economic injuries caused by public action be compensated by the Government, rather than remain disproportionately concentrated on a few persons… .Indeed, we have frequently observed that whether a particular restriction will be rendered invalid by the Government’s failure to pay for any losses proximately caused by it depends largely “upon the particular circumstances [in that] case.” Id. at 2659.Google Scholar

85. See, e.g., Final Report of the Governor’s Property Rights Study Commission 12-13 ([Tallahassee, Fla.] Mar. 17, 1975). The Florida legislature enacted, in 1978, a “property rights” bill, which provides, inter alia: Any person substantially affected by a final action of any agency with respect to a permit may seek review within 90 days of the rendering of such decision and request monetary damages and other relief in the circuit court in the judicial circuit in which the affected property is located; provided, however, that circuit court review shall be confined solely to determining whether final agency action is an unreasonable exercise of the state’s police power constituting a taking without just compensation. Ch. 78-85, Fla. Stats. West’s Fla. Sess. Law Service, 1978, no. 2, at 190. If the court determines the decision reviewed is an unreasonable exercise of the state’s police power constituting a taking without just compensation, the court shall remand the matter to the agency which shall, within a reasonable time: (1) Agree to issue the permit; or (2) Agree to pay appropriate monetary damages, provided however, in determining the amount of compensation to be paid, consideration shall be given by the court to any enhancement to the value of the land attributable to governmental action; or (3) Agree to modify its decision to avoid an unreasonable exercise of police power. Id. This act implemented some, but not all, of the recommendations of earlier studies. See also Florida, House of Representatives, Committee on Natural Resources, Seminar on “The Constitutional and Legal Limits to the Regulation of Private Land” (Tallahassee, Jan. 23-24, 1975); Van Alstyne, Statutory Modification, supra note 83; id., Taking or Damaging, supra note 83.Google Scholar

86. 11 Cal. App. 3d 557, 89 Cal. Rptr. 897 (1st Dist. Ct. App. 1970).Google Scholar

87. Id. at 572, 89 Cal. Rptr. at 906.Google Scholar

88. Id. Google Scholar

89. Id. Google Scholar

90. 195 Cal. 477, 234 P. 381 (1925), cert, denied, 273 U.S. 781 (1927).Google Scholar

91. 11 Cal. App. 3d 557, 89 Cal. Rptr. 897 (1st Dist. Ct. App. 1970).Google Scholar

92. Recent cases suggest that periods considerably longer than California’s interim three-year process might be upheld. Golden v. Planning Board of Ramapo, 30 N.Y.2d 359, 285 N.E.2d 291, 334 N.Y.S.2d 138, appeal dismissed, 409 U.S. 1003 (1972), for example, upheld a “timed growth” regulatory scheme that could conceivably restrict development in some areas for as long as 18 years. But there was a vague judicial uneasiness, a feeling of “something inherently suspect in a scheme which, apart from its professed purposes, effects a restriction upon the free mobility of a people until sometime in the future when projected facilities are available to meet increased demands.” Id. 285 N.E.2d at 300. Steel Hill Dev., Inc. v. Town of Sanbomton, 469 F.2d 956 (1st Cir. 1972), upheld small (1,000 population) Sanbornton’s six-acre minimum lot size requirement against a frustrated developer’s taking attack, based on precedents such as California’s Candlestick and New York’s Ramapo. Also cited was the interim program of Boulder, Colorado, which on an emergency basis restricted growth until an adequate study of future needs could be made. Again the court reflected judicial concern, wondering whether the motivation was exclusionary and calling for more homework.Google Scholar

93. ali Code, supra note 70, § 7-202(2).Google Scholar

94. Id. § 7-205.Google Scholar

95. Id., Reporters’ Note at 266. But cf. Home v. Board of Supervisors, No. 31309 (Va. Cir. Ct. 1974), striking down Fairfax County’s 18-month ban on building new subdivisions, town houses, apartments, and industrial complexes not already approved by the county. This interim development ordinance, enacted to prevent a “race of diligence,” while a permanent ordinance was being prepared is described in the Wash. Post, Jan. 14, 1975, at Al, col. 1.Google Scholar

96. Freilich, supra note 69; Comment, Zoning—a Time to Plan: Interim Zoning for Balanced Development in Rural New England, 53 B.U.L. Rev. 523 (1973).Google Scholar

97. The facts in this paragraph are drawn from Healy, Saving California’s Coast, supra note 19, at 380-83, and where specifically attributed, Joseph Bodovitz, telephone conversation. Champaign, 111. to Mill Valley, Cal., Nov. 17, 1978. Bodovitz emphasized that the coastal commissions were required to apply different standards than those applicable in the case of the earlier permits.Google Scholar

98. Id. (citing L.A. Times, Feb. 21, 1974).Google Scholar

99. See, e.g., Paul Sabatier, State Review of Local Land Use Decisions: The California Coastal Commissions (Draft, May 1976). Sabatier’s preliminary findings, based on a random sample of the approximately 4 percent of regional decisions that were appealed to the state commission from February 1973 to June 1975, include the following: “35% of the permit appeals involved large residential developments and fully 60% of all appeals involved some sort of residence.” But he found that “the rate of denials was roughly proportionate to the size of the development. Proposals for large multi-unit residences and motels had very rough sledding, with commercial and recreational facilities being denied over 40% of the time. The lone exceptions to the generalization involved lot splits and single family residences in rural subdivisions, which also had denial rates of over 40%.”Google Scholar

100. See, e.g., id. Google Scholar

101. Letter from Chairman M. B. Lane, 1975 Coastal Plan, supra note 1, at iv.Google Scholar

102. Interviews with Lorell Long, supra note 50, and Celia Von Der Muhll, American Institute of Planners, northern California coastal coordinator, Sierra Club, in Santa Cruz, Aug. 25, 1975, in which the latter cited the San Onofre nuclear plant decision as the “most blatant” capitulation to political pressure and also expressed general “disappointment” and criticism for “uneven” administration in Southern California, where she believed too many major developments that could have been denied were approved. An executive director of a regional commission, whom I shall not name, was complimentary of the quality of the state staff and commission members and was generally supportive of their implementation of the act, but he nevertheless concluded that “the record of their decisions bespeaks a significant amount of capricious, arbitrary, and uninformed actions.” He believed that the regional commissions were less likely to be arbitrary, capricious, and uninformed because of the more intensely focused attention on their decisions: “They may be capricious or wrong in the end, but they are certainly going to be watched more closely.” Interview, Feb. 1975.Google Scholar

103. Regulations of the California Coastal Zone Conservation Commission § 13210 (Jan. 23, 1974) (codifed in 14 Cal. Admin. Code, div. 5.5, repealed 1/19/77) [hereinafter cited as 1972 cczcc Regs.].Google Scholar

104. 1972 cczcA, supra note 3, § 27404.Google Scholar

105. Id. § 27405.Google Scholar

106. Id. § 27422; 1972 cczcc Regs., supra note 103, § 13010.Google Scholar

107. Statutory Comment, supra note 19, at 483.Google Scholar

108. 1972 cczcc Regs., supra note 103, §§ 13350-13351.Google Scholar

109. 43 Cal. App. 3d 306, 118 Cal. Rptr. 315 (4th Dist. Ct. App. 1974).Google Scholar

110. 55 Cal. App. 3d 889, 127 Cal. Rptr. 786 (1st Dist. Ct. App. 1975).Google Scholar

111. Id. at 895, 127 Cal. Rptr. at 790.Google Scholar

112. See, e.g., Patterson v. Central Coast Regional Coastal Zone Conservation Comm’n, 58 Cal. App. 3d 833, 838, 130 Cal. Rptr. 169, 172 (1st Dist. Ct. App. 1976).Google Scholar

113. Id. at 840, 130 Cal. Rptr. at 173 (citing Strumsky v. San Diego County Employee Retirement Ass’n, 11 Cal. 3d 28, 520 P.2d 29, 112 Cal. Rptr. 805 (1974)).Google Scholar

114. 1972 cczcA, supra note 3, § 27423(c).Google Scholar

115. rea Enterprises v. California Coastal Zone Comm’n, 52 Cal. App. 3d 596, 605, 125 Cal. Rptr. 201, 207 (2d Dist. Ct. App. 1975).Google Scholar

116. See, e.g., Patterson v. Central Coast Regional Coastal Zone Conservation Comm’n, 58 Cal. App. 3d 833, 130 Cal. Rptr. 169 (1st Dist. Ct. App. 1976).Google Scholar

117. Id. at 840, 130 Cal. Rptr. at 173.Google Scholar

118. 1972 cczcA, supra note 3, § 27202. The North Coast Regional Commission, for example, had 6 out of 12 members from local governments, i.e., a county supervisor and a city councilman from each of the three counties of Del Norte, Humboldt, and Mendocino. On the North Central Coast Regional Commission for Sonoma, Marin, and San Francisco counties the governmental representatives included one supervisor and one city councilman each from Sonoma County and Marin County, two supervisors of the City and County of San Francisco, and one delegate to the Association of Bay Area Governments to reflect the special regional interests of the larger San Francisco metropolitan area. Id. § 27202(b).Google Scholar

119. Id. § 27202.Google Scholar

120. Brown v. Superior Court, 15 Cal. 3d 52, 538 P.2d 1137, 123 Cal. Rptr. 377 (1975). One of Governor Reagan’s Dec. 1972 appointees, John Mayfield, was removed by Governor Brown on May 18, 1975. The California Supreme Court, in upholding the removal, explained: “The drafters and voters could reasonably choose to establish a commission of limited duration, but one composed of politically responsive members subject to removal by elected officials.” Id. at 56, 538 P.2d at 1139, 123 Cal. Rptr. at 379.Google Scholar

121. Sabatier, supra note 99.Google Scholar

122. Id. Google Scholar

123. See Gellhorn, Walter, When Americans Complain: Governmental Grievance Procedures 13 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1966), warning that while inflexibility may preclude some bad decisions, it equally precludes good ones.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

124. Interview v.ith Melvin Β. Lane, chairman, California Coastal Zone Conservation Commission, in Menlo Park, Feb. 12, 1975. See generally Scott, supra note 19, at 79-97 (“[Proponents of the ‘intelligent-layman’ model substantially outnumber those who argue for professional disciplinary and expertise requirements.” Id. at 97).Google Scholar

125. Lloyd Ν. Cutler & David R. Johnson, Regulation and the Political Process, 84 Yale L.J. 1395, 1405-6 (1975). Expert advice and the independence of those who give this advice are still of great importance, and ultimate decisionmakers cannot be without such counsel. However, as we are beginning to recognize, regulation today involves political choices between competing interests—concerning which economic and social goals to pursue, how far and at what economic and social costs. Under our constitutional scheme, these are choices that only politically accountable officials who are “dependent” rather than “independent” and “generalists” rather than “experts” should be making. Id. Google Scholar

126. ali Code, supra note 70, at § 8-101 note, at 303-4.Google Scholar

127. Id. at 305.Google Scholar

128. Id. at 306. See also Cutler & Johnson, supra note 125, at 1397, 1399, emphasizing the importance of political responsibility.Google Scholar

129. See, e.g., avco Community Developers, Inc. v. South Coast Regional Comm’n, 17 Cal. 3d 785, 553 P.2d 546, 132 Cal. Rptr. 386 (1976), appeal dismissed, 97 S. Ct. 1089 (1977); San Diego Coast Regional Comm’n v. See the Sea, Ltd., 9 Cal. 3d 888, 513 P.2d 129, 109 Cal. Rptr. 377 (1973); California Cent. Coast Regional Comm’n v. McKeon Const., 38 Cal. App. 3d 154, 112 Cal. Rptr. 903 (1st Dist. Ct. App. 1974); Coastal Southwest Dev. Corp. v. California Coastal Zone Conservation Comm’n, 55 Cal. App. 3d 525, 127 Cal. Rptr. 775 (4th Dist. Ct. App. 1976); No Oil, Inc. v. Occidental Petroleum Corp., 50 Cal. App. 3d 8, 123 Cal. Rptr. 589 (2d Dist. Ct. App. 1975); Oceanic California, Inc. v. North Central Coast Regional Comm’n, 63 Cal. App. 3d 57, 133 Cal. Rptr. 664 (1st Dist. Ct. App. 1976), appeal dismissed, 97 S. Ct. 2668 (1977); Patterson v. Central Coast Regional Coastal Zone Conservation Comm’n, 58 Cal. App. 3d 833, 130 Cal. Rptr. 169 (1st Dist. Ct. App. 1976); Transcentury Properties, Inc. v. State, 41 Cal. App. 3d 835, 116 Cal. Rptr. 487 (1st Dist. Ct. App. 1974).Google Scholar

130. 1972 cczcA, supra note 3, § 27404.Google Scholar

131. 17 Cal. 3d 785, 791, 553 P.2d 546, 550, 132 Cal. Rptr. 386, 389 (1976).Google Scholar

132. Interview with Stanley Scott, assistant director, Institute of Governmental Studies, University of California, in Berkeley, Feb. 11, 1975. See generally Scott, supra note 19, at 61-63, 72-73 (“Perhaps the most widely recognized and universally applauded characteristic of the coastal commissions is their visibility and the ‘open’ style with which they transact public business. This is a powerful asset.” Id. at 61).Google Scholar

133. Interview with H. J. Frazier, executive vice-president, Half Moon Bay Properties, Inc., in Half Moon Bay, Cal., Feb. 15, 1975.Google Scholar

134. Ellman interview, supra note 66.Google Scholar

135. Krueger interview, supra note 23.Google Scholar

136. California has “1,072 miles of mainland shoreland (excluding San Francisco Bay) and 397 miles of offshore island shoreland.” California Coastal Zone Conservation Commissions, Annual Report 1974, at 4.Google Scholar

137. Interview with Paul Sedway, Sedway/Cooke Urban Planners, in San Francisco, Feb. 10, 1975.Google Scholar

138. See notes 224-25 infra and text at same.Google Scholar

139. Bodovitz interview, supra note 46.Google Scholar

140. Interview with John Lahr, executive director, North Coast Regional Commission, in Eureka, Feb. 17, 1975.Google Scholar

141. Id. Humboldt is the most important timber-producing county, followed by Mendocino and Del Norte. Id. Google Scholar

142. Id. Google Scholar

143. Petaluma, California, just north of San Francisco, is well known for its growth-control efforts. See Construction Indus. Ass’n v. City of Petaluma, 522 F.2d 897 (9th Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 424 U.S. 934 (1976) (the Ninth Circuit refused to consider, on grounds of lack of standing, the federal right-to-travel issue upon which the district court had rested its decision in finding unconstitutional the “Petaluma Plan” for controlling the influx of new residents).Google Scholar

144. Lahr interview, supra note 140.Google Scholar

145. Id. Google Scholar

146. Interview with David Ν. Smith, head, Coastal Plan Division, South Coast Regional Commission, in Long Beach, Feb. 18, 1975.Google Scholar

147. Id. Google Scholar

148. Cf. Coalition for Los Angeles County Planning in the Public Interest v. Board of Supervisors, Civ. No. C-63218 (Super. Ct. Los Angeles County, Mar. 12, 1975) (relationship of plans to regulations).Google Scholar

149. See Milton Marks & Stephen L. Taber, Prospects for Regional Planning in California, 4 Pac. L.J. 117, 142 (1973). Cf. notes 203-14 infra and text at same.Google Scholar

150. 1975 Coastal Plan, supra note 1, at 12.Google Scholar

151. Interview with Janet K. Adams, executive director, California Coastal Alliance, in Woodside, Cal., May 27, 1975.Google Scholar

152. Von der Muhll interview, supra note 102 (“disappointed” but recognized that it “possibly deterred development,” citing “almost no new development in open underdeveloped areas”); interview with Lucille Vinyard, Sierra Club, in Trinidad Beach, Cal. (north of Eureka), Feb. 17, 1975. Perhaps the most sobering environmental evaluation was by the vice-chairperson of the state coastal commission who suggested that “passage of the act may have even stimulated development.” Interview with Ellen Stern Harris, in Los Angeles, Feb. 19, 1975.Google Scholar

153. Bodovitz interview, supra note 46.Google Scholar

154. Crandall interview, supra note 68.Google Scholar

155. Fischer interview, supra note 17.Google Scholar

156. Crandall interview, supra note 68.Google Scholar

157. The point was made in several interviews, e.g., Frazier interview, supra note 133.Google Scholar

158. See, e.g., Hagman, Donald G., Windfalls for Wipeouts, in American Assembly, Columbia University, The Good Earth of America: Planning Our Land Use 109 (C. Lowell Harriss, ed. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1974).Google Scholar

159. The shift, even possible increase, of activity in areas outside the 1,000-yard permit zone was observed, for example, by an environmentally oriented state commissioner (Harris interview, supra note 152) and a developers’ attorney (Ellman interview, supra note 66).Google Scholar

160. Following a court decision requiring an environmental impact report (eir) for major timber-cutting projects, there was a major north coast reaction, including a demonstration by 1,300 loggers at the state capítol in Sacramento (S.F. Examiner & Chronicle, Feb. 9, 1975, at 5) and a Eureka rally of 2,500 citizens representing loggers, industry, agriculture and business unions, and others, testifying to the effects of the Forest Practices Act and the California Environmental Quality Act on the north coast economy. (Humboldt Beacon, Feb. 13, 1975, at 1, col. 5, under headline, “State Labor Chief Shouts ‘We Will Now March on Sierra Club.’ “)Google Scholar

161. See note 257 infra. Governor Brown immediately attempted to simplify the reporting requirement and speed up the processing of timber-cutting plans. L.A. Times, Feb. 20, 1975, at 26, col. 5.Google Scholar

162. Interviews with Raymond Peart, former county supervisor, and Dwight May, former member of the North Coast Regional Commission, in Eureka, Feb. 17, 1975.Google Scholar

163. Healy, supra note 19, at 372 et seq. Google Scholar

164. L.A. Times, June 12, 1976, at 1, col. 5.Google Scholar

165. Id. Google Scholar

166. Senator Roberti’s views are those reported in id. and as recorded by me at the legislative hearing in Sacramento, June 23, 1976.Google Scholar

167. Interview with James M. Dennis, Esq. in Redwood City, Cal., May 27, 1975.Google Scholar

168. See, e.g., 1975 Coastal Plan, supra note 1, at 152-55.Google Scholar

169. Legislative hearing, supra note 166.Google Scholar

170. All of the following facts about Westinghouse’s Half Moon Bay project, unless otherwise noted, were obtained from extensive interviews with H. J. Frazier, then executive vice-president, Half Moon Bay Properties, Inc., in Half Moon Bay, Cal., Feb. 15, 1975, Aug. 27, 1975, and June 27, 1976. Mr. Frazier, now president of Half Moon Bay Properties, Inc., emphasized that his views are those of the wholly owned subsidiary, not necessarily those of Westinghouse Electric Corporation. Telephone conversation with H. J. Frazier, Chicago to Half Moon Bay, Nov. 6, 1978. Nevertheless, for convenience, Half Moon Bay Properties, Inc. will hereinafter often be referred to as Westinghouse.Google Scholar

171. Cf., e.g., Southern Burlington County naacp v. Township of Mt. Laurel, 67 N.J. 151, 336 A.2d 713, appeal dismissed, 423 U.S. 808 (1975).Google Scholar

172. 1975 California Coastal Plan, supra note 1, at 228.Google Scholar

173. Id. Google Scholar

174. Id. Google Scholar

175. Interview with W. Fred Mortensen, city manager of Half Moon Bay and general manager of the sewer authority, mid-coastside, in Half Moon Bay, Cal., Mar. 20, 1978.Google Scholar

176. See The Federal Role, supra note 54, for a detailed discussion of many of the federal programs.Google Scholar

177. See fig. 2 infra for subsequent increases in prices.Google Scholar

178. See fig. 2 infra for subsequent increases in prices.Google Scholar

179. 58 Cal. App. 3d 149, 129 Cal. Rptr. 743 (1st Dist. Ct. App. 1976).Google Scholar

180. Id. at 153, 129 Cal. Rptr. at 746.Google Scholar

181. Id. Google Scholar

182. 17 Cal. 3d 785, 553 P.2d 546, 132 Cal. Rptr. 386 (1976), appeal dismissed, 97 S. Ct. 1089 (1977).Google Scholar

183. Id. at 788, 553 P.2d at 548, 132 Cal. Rptr. at 388.Google Scholar

184. Id. at 795, 553 P.2d at 552, 132 Cal. Rptr. at 392. This court rejected the developer’s argument that two earlier cases were distinguishable: Spindler Realty Corp. v. Monning, 243 Cal. App. 2d 255, 53 Cal. Rptr. 7 (2d Dist. Ct. App. 1966); Anderson v. City Council, 229 Cal. App. 2d 79, 40 Cal. Rptr. 41 (1st Dist. Ct. App. 1964).Google Scholar

185. See notes 371-91 infra and text at same.Google Scholar

186. Frazier telephone conversation, supra note 170.Google Scholar

187. Interview with H. J. Frazier, president, Half Moon Bay Properties, Inc., in San Francisco, Mar. 15, 1978.Google Scholar

188. See fig. 2 supra. Google Scholar

189. Frazier telephone conversation, supra note 170.Google Scholar

190. Frazier interview, supra note 187.Google Scholar

191. Frazier telephone conversation, supra note 170.Google Scholar

192. 426 U.S. 668 (1976).Google Scholar

193. Supra note 2.Google Scholar

194. Cal. Gov’t Code §§ 65037-65040.7 (West Supp. 1966-77).Google Scholar

195. Id. § 65040(a).Google Scholar

196. He restricted its principal function to preparation of an environmental goals and policy report. Id. § 65041. The first was due in Mar. 1976. Interview with Edmond C. Baume, Office of Planning and Research, in Sacramento, Feb. 13, 1975.Google Scholar

197. Baume interview, supra note 196.Google Scholar

198. Interview with an official, Office of Planning and Research in Sacramento, June 23, 1976.Google Scholar

199. L.A. Times, Nov. 21, 1976, § 7, at 1,4, col. 5.Google Scholar

200. Id. Google Scholar

201. See notes 246-56 infra and text at same.Google Scholar

202. 1976 cca, supra note 2, § 30415 (1977). See also City of Chico v. County of Butte, Stipulation and Waiver of Notice, No. 14553 (Super. Ct., County of Colusa, Cal. Oct. 1976) and attached Application for Extension of Time, Before the Director of Planning and Research.Google Scholar

203. California Land-Use Task Force, Planning and Conservation Foundation, Report: California Land Planning for People 30 (Los Altos, Cal.: William Kaufmann, Inc., 1975) [hereinafter cited as California Land Use Report).Google Scholar

204. Id. at 84. Several other California observers, whose views on other subjects often were in conflict, also pointed to this need for a better state comprehensive planning process. E.g., interview with John Abbott, executive director, California Tomorrow, in San Francisco, Feb. 11, 1975; Interview with E. Clement Shute, Jr., assistant attorney general, state of California, in San Francisco, Feb. 10, 1975; Sedway interview, supra note 137; Ellman interview, supra note 66; interview with Roger Hedgecock, Esq. (counsel for the Sierra Club), in San Diego, Feb. 20, 1975 (“priority of the Sierra Club legislative program”).Google Scholar

205. Baume interview, supra note 1%.Google Scholar

206. Interview with Edmond C. Baume, chief, State Planning Division, Office of Planning and Research, in Sacramento, Aug. 26, 1975. Thomas H. Willoughby, consultant, Assembly Committee on Local Government, emphasized this relationship of transportation policy to coastal policy. A decision to open up access to a certain part of the coastline, he believed, should be consistent with the coastal plan. Such potential conflicts point up the need for an “integrated, statewide program.” Interview, in Sacramento, Feb. 14, 1975.Google Scholar

207. Interview with Eugene Varanini, consultant, Assembly Committee on Energy and Diminishing Materials, in Sacramento, Feb. 14, 1975.Google Scholar

208. See 1976 cca, supra note 2, § 30413 (1977).Google Scholar

209. Lane interview, supra note 124; the 1975 Coastal Plan, supra note 1, at 115, recommended such coordination.Google Scholar

210. Inferences drawn from interviews with Michael Madigan, assistant to Mayor Pete Wilson for program and policy development, mayor’s office, in San Diego, Feb. 20, 1975; Crandall interview, supra note 68. The League of California Cities also strongly supported a statewide planning system, explaining the relationship to coastal planning: [C]ity officials believe that the coast can only be effectively governed and managed if decisions affecting transportation, housing and pollution regulation are integrated into a statewide planning process … [and] if the structure which implements the policies is able to respond to federal and statewide policies and programs. League of California Cities Coastal Plan Review Committee’s summary of the league’s position on the government powers and funding element of the preliminary coastal plan [Sacramento, Sept. 1975],Google Scholar

211. “As little as four or five years ago, state land-use planning was considered some kind of 21st century idea … But things like the energy crisis have all of a sudden impressed upon a lot of people that we do have to start planning how we use our resources.” Willoughby interview, supra note 206. However, according to the deputy executive director of the California Coastal Commission, in the post-Proposition 13 climate in California, “state comprehensive land use planning is not a popular subject.” Telephone conversation with Peter Douglas, Champaign, 111., to Sacramento, Nov. 14, 1978.Google Scholar

212. “I see [the legislature passing] more individual kinds of programs—coastal programs, prime agricultural lands programs. Finally the whole thing will get into such a mess that they will finally realize there has to be some way of resolving the conflicts.” Interview with David F. Beatty, Esq., League of California Cities, in Sacramento, June 23, 1976.Google Scholar

213. au Code, art. 8, at 291-361.Google Scholar

214. See note 204 supra. But cf. Douglas telephone conversation, supra note 211. The 1975 United Nations report on coastal area management and development drew attention to “over 100 state and federal agencies” with jurisdiction over the coastal area of California. The report was concerned about the effects of overlapping of intragovernmental responsibilities in coastal planning: Classically, government departments are organized on a functional basis. Thus, transport, power, trade and industry, internal affairs, external affairs, agriculture, and tourism are typical government departments. Those departments are each vertically integrated, but the horizontal linkages between those agencies, which are necessary for comprehensive management of all the sectors along the coast, are often absent. Furthermore, a governmental structure defined along those lines faces a jurisdictional ambiguity at the shoreline. Coastal Area Management and Development, Report of the Secretary-General, United Nations Economic and Social Council, 59th Sess., May 8, 1975, at 12.Google Scholar

215. See note 371 infra and text at same.Google Scholar

216. See notes 289-90 infra and text at same.Google Scholar

217. Cal. Gov’t Code §§ 6500-6515 (West 1966 & Cum. Supp. 1978).Google Scholar

218. Id. §§ 66600-66661 (West 1966 & Supp. 1966-77).Google Scholar

219. Tahoe Regional Planning Compact, Pub. L. No. 91-148, 83 Stat. 360, approved Dec. 18, 1969.Google Scholar

220. 1976 cca, supra note 2, § 30305 (1977).Google Scholar

221. West’s Cal. Legis. Serv. 1978, no. 4, at xxv-xxvi.Google Scholar

222. Regional Planning Districts, Cal. Gov’t Code §§ 65060-65069 (West 1966 & Supp. 1966-77); Area Planning, Cal. Gov’t Code §§ 65600-65604 (West 1966 & Supp. 1966-77); District Planning Law, Cal. Gov’t Code §§ 66100-66390 (West 1966 & Supp. 1966-77).Google Scholar

223. California Land Use Report, supra note 203, at 22.Google Scholar

224. Id. at 23.Google Scholar

225. Id. Google Scholar

226. 42 U.S.C. §§ 3301-3374 (1970 & Supp. V 1975).Google Scholar

227. 42 U.S.C. §§ 4201-4244 (1970 & Supp. V 1975).Google Scholar

228. Circular A-95, U.S. Office of Management and Budget. See ali Code, supra note 70, § 8-102, at 309-15.Google Scholar

229. See, e.g., Melvin Β. Mogulof, Regional Planning, Clearance, and Evaluation: A Look at the A-95 Process, 37 J. Am. Inst. Planners 419 (1971). See generally ali Code, supra note 70, at 309-15.Google Scholar

230. ali Code, supra note 70, at 312 (quoting Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations, Regional Decision Making: New Strategies for Substate Districts 109 (1973)).Google Scholar

231. Id. at 311.Google Scholar

232. Mogulof, supra note 229, at 412.Google Scholar

233. ali Code, supra note 70, at 312 (citing National Academy of Sciences and National Academy of Engineering, Revenue Sharing and the Planning Process 26 (1974)).Google Scholar

234. See, e.g., in addition to the programs analyzed in my study Coastal Land Management: An Introduction, 1978 A.B.F. Research J. 153, Minn. Stat. Ann. §§ 473.851-.872 (West 1977). See generally, 2 Grad, Frank P., Treatise on Environmental Law § 10.03 et seq. (New York: Matthew Bender, 1977); Daniel R. Mandelker, Environmental and Land Controls Legislation (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1976); Bosselman & Callies, supra note 9; Robert H. Freilich & John W. Ragsdale, Jr., Timing and Sequential Controls—the Essential Basis for Effective Regional Planning: An Analysis of the New Directions for Land Use Control in the Minneapolis-St. Paul Metropolitan Region, 58 Minn. L. Rev. 1009 (1974).Google Scholar

235. The San Francisco Bay area is an exception. Assemblyman Knox has pushed for a regional government there. One bill came close to passage in 1974; its 1975 counterpart was defeated by a larger margin. However, “there is still a lot of support in the Bay Area for regional government,” and it is possible that an act establishing regional government for the San Francisco Bay area will eventually pass. Telephone interview, William Press, then-deputy director, Office of Planning and Research, Sacramento, Nov. 3, 1975.Google Scholar

236. The succeeding article in this series will deal at length with this development in Florida, as a consequence of Florida’s development of regional impact process, Fla. Stat. Ann. § 380.06, et seq. (West 1974 & Cum. Supp. 1978).Google Scholar

237. Cf. generally The Federal Role, supra note 54, at 259-68 & nn. 488-557.Google Scholar

238. See Cal. Gov’t Code §§ 66600-66661 (West 1966 & Supp. 1966-77). See also Bosselman & Callies, supra note 9, at 108-35.Google Scholar

239. S.F. Chronicle, Feb. 10, 1975, at 30, col. 1.Google Scholar

240. San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission, San Francisco Bay Plan 1 (1969).Google Scholar

241. See California Land Use Report, supra note 203, at 25.Google Scholar

242. See note 285 infra and text at same.Google Scholar

243. Cal. Gov’t Code § 66610 (West Supp. 1966-77).Google Scholar

244. 1976 cca, supra note 2, § 30103 (1977).Google Scholar

245. California Land Use Report, supra note 203.Google Scholar

246. Cal. Gov’t Code § 65300 (West 1966).Google Scholar

247. Id. §§ 65302-65303 (West Supp. 1966-77).Google Scholar

248. Id. § 65800.Google Scholar

249. Id. § 65860.Google Scholar

250. See notes 379-82 infra and text at same.Google Scholar

251. Cal. Gov’t Code § 65566 (West Supp. 1966-77).Google Scholar

252. See Coalition for Los Angeles County Planning in the Public Interest v. Board of Supervisors, Civ. No. C-63218 (Super. Ct. Los Angeles County Mar. 12, 1975).Google Scholar

253. Interview with David F. Beatty, Esq., League of California Cities, in Sacramento, Aue. 26, 1975.Google Scholar

254. Bodovitz interview, supra note 46; Sedway interview, supra note 137.Google Scholar

255. “I don’t think you can point to many places in the country where zoning and planning have protected areas against persistent, long-term development pressure; you can’t point to many places in California that have been protected for any length of time by zoning and local governments’ mandated plans.” Bodovitz interview, supra note 46.Google Scholar

256. Interview with Frederick G. Styles, principal consultant, Office of Research, California State Assembly, in Sacramento, Feb. 13, 1975. See also California Land Use Report, supra note 203, at 26-27, which voiced similar conclusions about the shortcomings of the local planning approach.Google Scholar

257. Cai. Pub. Res. Code §§ 21000-21172 (West 1977 & Cum. Supp. 1978).Google Scholar

258. 42 U.S.C. §§ 4331-4347 (1970 & Supp. V 1975).Google Scholar

259. Cai. Pub. Res. Code § 21100 (West 1977).Google Scholar

260. 8 Cal. 3d 247, 502 P.2d 1049, 104 Cal. Rptr. 761 (1972).Google Scholar

261. Id. at 253, 502 P.2d at 1052, 104 Cal. Rptr. at 764.Google Scholar

262. Cal. Pub. Res. Code § 21100(a)-(g) (West 1977).Google Scholar

263. Bodovitz interview, supra note 46.Google Scholar

264. Fischer interview, supra note 17.Google Scholar

265. See also Sedway/Cooke, for the Planning and Conservation Foundation, Land and the Environment: Planning in California Today (Los Altos, Cal.: William Kaufmann, Inc., 1975); Sedway interview, supra note 137.Google Scholar

266. Cai. Pub. Res. Code §§ 21002, 21002.1, 21003 (West 1977).Google Scholar

267. Bodovitz interview, supra note 46.Google Scholar

268. Lahr interview, supra note 140. See notes 160-61 supra. Google Scholar

269. Supra note 2.Google Scholar

270. 1976 cca, supra note 2, § 30004(a) (1977).Google Scholar

271. Id. § 30108.6.Google Scholar

272. Id. §§ 30510-30522.Google Scholar

273. Id. §§ 30512-30513.Google Scholar

274. Id. § 30514(a).Google Scholar

275. Id. § 30600(a).Google Scholar

276. Id. §§ 30600(d); 30519.Google Scholar

277. Id. § 30600(c).Google Scholar

278. Id. § 30304.5(b)-(c).Google Scholar

279. Id. § 30305, as amended by ch. 1076, 1978 Laws, West’s Calif. Legis. Serv. 1978.Google Scholar

280. Id. § 30317.Google Scholar

281. Id. § 30501(b), as amended by ch. 1075, 1978 Laws, West’s Calif. Legis. Serv. 1978 (if prepared by local government, must be submitted by Jan. 1, 1981, or if prepared by state commission, must be certified not later than June 1, 1981).Google Scholar

282. Id. § 30200-30264 (1977 & Cum. Supp. 1978).Google Scholar

283. Id. § 30512(e). Cf. notes 380-88 infra and text at same.Google Scholar

284. The permit shall be issued if the development “is in conformity with” the policies and if the “development will not prejudice the ability of the local government to prepare a local coastal program.” Id. § 30604(a).Google Scholar

285. 1975 California Coastal Plan, supra note 1.Google Scholar

286. See Daniel R. Mandelker, The Role of the Local Comprehensive Plan in Land Use Regulation, 74 Mich. L. Rev. 900 (1976), where Professor Mandelker notes that although “[t]he Standard State Zoning Enabling Act did contain enigmatic language stating simply that zoning ‘shall be in accordance with a comprehensive plan’ “ (id. at 902), “[t]he early judicial interpretations of the statutes almost uniformly accepted a narrow reading that the ‘comprehensive plan’ with which zoning must be ‘in accordance’ could be found within the text of the zoning ordinance.” Id. at 904.Google Scholar

287. See, e.g., Florida’s Local Government Comprehensive Planning Act of 1975, Fla. Stat. Ann. §§ 163.3161-.3211 (West Cum. Supp. 1978).Google Scholar

288. See, e.g., notes and text at id. § 163.3194, and Mandelker, supra note 286, at 906 (“Florida has recently adopted a consistency provision that is both more focused and more extensive in scope than that of California… .Perhaps even more far-reaching, however, is its application of the policies of the plan to ‘development orders’ by governmental agencies.” Id. at 960, 961).Google Scholar

289. Henry M. Hart, Jr., & Albert M. Sacks, The Legal Process: Basic Problems in the Making and Application of Law (Tentative ed., Cambridge, Mass., 1958).Google Scholar

290. Id. at 155-60.Google Scholar

291. 1976 cca, supra note 2, ch. 3, §§ 30200-30264 (1977 & Cum. Supp. 1978).Google Scholar

292. See note 305 infra and text at same.Google Scholar

293. U.S., Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Coastal Zone Management & California Coastal Commission, Combined State of California Coastal Management Program (Segment) and Final Environmental Impact Statement 17 (Aug. 1977) [hereinafter cited as California Coastal eis],Google Scholar

294. Id. See notes 42-50 supra and text at same.Google Scholar

295. 1975 Coastal Plan, supra note 1.Google Scholar

296. 1976 cca, supra note 2.Google Scholar

297. Cf., e.g., Berger, supra note 78, at 686.Google Scholar

298. See The Federal Role, supra note 54, at 221-29 & nn. 290-324.Google Scholar

299. See American Petroleum Inst. v. Knecht, 12 E.R.C. 1193 (D.C.D. Cal. 1978), in which the court denied an injunction barring department of commerce approval of the California coastal zone management program.Google Scholar

300. 1976 cca, supra note 2, § 30604(a), (b) (1977).Google Scholar

301. See Just v. Marinette County, 56 Wis. 2d 7, 201 N.W.2d 761 (1972) (“[TJhis depreciation of value is not based on the use of the land in its natural state but on what the land would be worth if it could be filled and used for the location of a dwelling [V]alue based upon changing the character of the land at the expense of harm to public rights is not an essential factor or controlling,” 56 Wis. 2d at 19, 201 N.W.2d at 771).Google Scholar

302. Michelman, supra note 83.Google Scholar

303. See 1 Williams, supra note 11, § 6.03, at 115.Google Scholar

304. Schumacher, E. F., Small Is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered 252 (New York: Harper & Row, 1973).Google Scholar

305. Id. at 250-51.Google Scholar

306. Id. at 243.Google Scholar

307. See notes 13-16 supra and text at same for discussion of statutory and constitutional home rule.Google Scholar

308. Schumacher, supra note 304, at 244.Google Scholar

309. Id. at 243.Google Scholar

310. Id. Google Scholar

311. Id. at 246. This Statement is more an admonition to the legal architect of coastal management arrangements than a criticism of public servants. Administrators must work within their statutory mandates, and some problems attributed to administrators are caused by bad drafting of legislation.Google Scholar

312. Bodovitz interview, supra note 46.Google Scholar

313. Ellman interview, supra note 66.Google Scholar

314. Gralnek interview, supra note 31.Google Scholar

315. Von der Muhll interview, supra note 102.Google Scholar

316. Crandall interview, supra note 68. See also Scott, supra note 19, at 58.Google Scholar

317. Gralnek interview, supra note 31.Google Scholar

318. “The level of generality is necessarily very gross.” Interview with Paul Sedway, Sedway/Cooke Urban Planners, in San Francisco, June 21, 1976.Google Scholar

319. “1 don’t think anyone knows the answer.” Beatty interview, supra note 212.Google Scholar

320. Sedway interview, supra note 137.Google Scholar

321. Baume interview, supra note 206.Google Scholar

322. Smith interview, supra note 146. He was head of the coastal plan division of the South Coast Regional Commission.Google Scholar

323. See Lahr interview, supra note 140.Google Scholar

324. 1976 cca, supra note 2, § 30001.5(d) (1977).Google Scholar

325. Id. § 30222.Google Scholar

326. See notes 163-67 supra and text at same.Google Scholar

327. Interview with Joseph Petrillo, in Sacramento, June 22, 1976.Google Scholar

328. Appropriate geographical coverage is determined not only by physical aspects of the land (e.g., wetlands regulation may have to extend to adjacent transitional areas) and the intent of the legislation (e.g., regulations to prevent the obstruction of scenic views will differ from regulations to protect habitats) but also by the ability of local governments to manage an area (e.g., budget limitations may preclude adequate supervision of a large area).Google Scholar

329. 16 U.S.C. § 1453 (1) (1976).Google Scholar

330. Beatty interview, supra note 212.Google Scholar

331. See notes 203-16 supra and text at same.Google Scholar

332. Bodovitz interview, supra note 46.Google Scholar

333. Ellman interview, supra note 66.Google Scholar

334. Von der Muhll interview, supra note 102.Google Scholar

335. Lahr interview, supra note 140.Google Scholar

336. Gralnek interview, supra note 31.Google Scholar

337. 1976 cca, supra note 2, § 30103(a) (1977).Google Scholar

338. Id. § 30103(b).Google Scholar

339. Id. § 30103(a).Google Scholar

340. See 1975 Coastal Plan, supra note 1, at 54-61, and maps at 278 el seg. Google Scholar

341. 1976 cca, supra note 2, § 30103(a) (1977).Google Scholar

342. Id. § 30610.5.Google Scholar

343. Id. § 30103.Google Scholar

344. Interview with Richard Β. (Ben) Mierenet, assistant Pacific regional manager, Office of Coastal Zone Management, in Washington D.C., Mar. 31, 1977.Google Scholar

345. Cf. 1 Williams, supra note 11, § 1.07, at 13.15.Google Scholar

346. Beatty interview, supra note 253. Paul Sedway, the San Francisco urban planner, believed state funds should be supplied for implementation. Sedway interview, supra note 137.Google Scholar

347. Frazier telephone interview, supra note 170.Google Scholar

348. See note 386 infra and text at same.Google Scholar

349. California Coastal eis, supra note 293, at 95.Google Scholar

350. Id. See 1976 cca, supra note 2, § 30516(a) (1977), which supports the eis statement that “the Coastal Commission cannot withhold approval of a local coastal program ‘because of the inability of the local government to financially support or implement any policy or policies’ of the Coastal Act, though this does not require approval of a program ‘allowing development not in conformity with the policies’ of the Coastal Act.” See also Cal. Rev. & Tax Code § 2231(a) (West 1970 & 1978 Supp.).Google Scholar

351. Id. Google Scholar

352. California Coastal eis, infra note 399, at 77.Google Scholar

353. Cf., e.g., Associated Home Builders v. City of Walnut Creek, 4 Cal. 3d 633, 484 P.2d 606, 94 Cal. Rptr. 630 (1971) (subdivision exactions); 1976 cca, supra note 2, § 30620(c) (1977) (“reasonable filing fee and the reimbursement of expenses for the processing by the regional commission or the commission of any application for a coastal development permit”); John J. Costonis, Development Rights Transfer: An Exploratory Essay, 83 Yale L.J. 75, 109-14 (1973). See also Proposition 13: A Clamp on Land Use, in the Wash. Post., Sept. 21, 1978, § A25, at col. 1, which contains the following: “[Proposition 13] is threatening to place a clamp on new residential development potentially more effective than any existing land-use law. The result could be a curb on the sprawl development often so harmful to cities and established suburbs. … Of all the effects, the joker in the deck, the effect practically no one anticipated, is the damper on new development… . The likely result: a slowdown in new subdivision construction, a sharp shift in costs to developers and, at least in some cities and suburbs, a virtual freeze on new subdivision building. … At a minimum, Proposition 13 now seems certain to drive up California’s already sky-high housing prices. The increased costs will be a heavy blow to low-income people and make mincemeat of Howard Jarvis’s pre-vote claim that Proposition 13 would make housing more affordable to young households by reducing property taxes.”Google Scholar

354. See notes 170-92 supra and text at same.Google Scholar

355. Frazier telephone interview, supra note 170. Mr. Frazier did not estimate the components of these figures.Google Scholar

356. See Federal Coastal Zone Management Act, §§ 302, 303, 16 U.S.C. §§ 1451, 1452 (1976).Google Scholar

357. 1976 cca, supra note 2, § 30001 (1977).Google Scholar

358. See generally id. §§ 30200-30264 (1977 & Cum. Supp. 1978).Google Scholar

359. Id. §§ 30255 (1977).Google Scholar

360. Id. §§ 30220-30224.Google Scholar

361. Lahr interview, supra note 140.Google Scholar

362. Smith interview, supra note 146; Crandall interview, supra note 68; Bodovitz telephone interview, supra note 97.Google Scholar

363. Varanini interview, supra note 207.Google Scholar

364. 1972 cczcA, supra note 3, §§ 27301, 27001(b).Google Scholar

365. E.g., Crandall interview, supra note 68; Smith interview, supra note 146.Google Scholar

366. Von der Muhll interview, supra note 102.Google Scholar

367. Long interview, supra note 50. On balance, her evaluation of the commission was favorable.Google Scholar

368. ali Code, supra note 70, § 8-405(1), at 346.Google Scholar

369. Id. § 8-601-02.Google Scholar

370. 1976 cca, supra note 2, § 30519.5 (1977).Google Scholar

371. Id. § 30200.Google Scholar

372. Id. § 30108.6.Google Scholar

373. Id. §§ 30500, 30510.Google Scholar

374. Id. §§ 30512-30513.Google Scholar

375. Id. § 30501(b), as amended by ch. 1075, 1978 Laws, West’s Calif. Legis. Serv. 1978 (if prepared by local government, must be submitted by Jan. 1, 1981, or if prepared by state commission, must be certified not later than June 1, 1981).Google Scholar

376. Id. § 30514.Google Scholar

377. Id. § 30500(c).Google Scholar

378. Interview with David Beatty, Esq., League of California Cities, in Sacramento, Nov. 23, 1976 (very favorable); interview with Tim Leslie, principal legislative representative, County Supervisors Association of California, in Sacramento, Nov. 22, 1976 (guardedly favorable).Google Scholar

379. 1976 CCA, supra note 2, § 30511 (1977).Google Scholar

380. Id. § 30511(b).Google Scholar

381. Id. §§ 30108.5, 30512(c).Google Scholar

382. Id. § 30513(a).Google Scholar

383. Telephone interview, Peter Douglas, deputy director, California Coastal Commission, Chicago to Sacramento, Nov. 20, 1978.Google Scholar

384. Telephone interview, Peter Douglas, deputy director, California Coastal Commission, in Sacramento, Apr. 15, 1977.Google Scholar

385. See, e.g., 1976 cca, supra note 2, § 30512(a) (1977).Google Scholar

386. Frazier telephone interview, supra note 170.Google Scholar

387. Bodovitz telephone interview, supra note 97.Google Scholar

388. See generally Dickert, Thomas, Sorensen, Jens, Hyman, Rick, Burke, James, Collaborative Land-Use Planning for the Coastal Zone: Volume 2, Half Moon Bay Case Study, prepared under the sponsorship of noaa, Office of Sea Grant, Department of Commerce, Sea Grant Publication no. 53 (Berkeley: Institute of Urban & Regional Development, University of California, 1976).Google Scholar

389. California Coastal Commission Local Coastal Program Regulations (adopted May 17, 1977), in California Coastal eis, supra note 293, at 5-1. See generally, for a discussion of the requirements of the fczma, my article, The Federal Role, supra note 54, at 250-53 & nn. 428-48.Google Scholar

390. See 1976 cca, supra note 2, § 30006 (1977); Local Coastal Program Regulations, supra note 389.Google Scholar

391. Telephone interview, San Francisco, Nov. 17, 1978.Google Scholar

392. Paul Sedway & Bonnie Loyd, Building Block Zoning Provides New Flexibility, 7 Practicing Planner, vol. 7, no. 3, at 26, 29.Google Scholar

393. See generally my article, Coastal Land Management: An Introduction, 1978 A.B.F. Research J. 153, at 159-64.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

394. 1976 cca, supra note 2, § 30600(a) (1977).Google Scholar

395. Id. § 30600(d).Google Scholar

396. Id. § 30600(c).Google Scholar

397. Id. § 30600(b). Peter Douglas cited city of Los Angeles ordinance no. 151, approved Oct. 11, 1978. Douglas telephone interview, supra note 383.Google Scholar

398. 1976 cca, supra note 2, § 30604 (1977).Google Scholar

399. U.S., Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Coastal Zone Management & California Coastal Commission, Combined State of California Coastal Management Program and Revised Draft Environmental Impact Statement [1977],Google Scholar

400. The proposed development must be “in conformity with the certified local coastal program.” 1976 ccA, supra note 2, § 30604(b) (1977). And every proposal, whether before or after certification, “issued for any development between the nearest public road and the sea or the shoreline of any body of water located within the coastal zone shall include a specific finding that such development is in conformity with the public access and public recreation policies” of the 1976 act. Id. 30604(c).Google Scholar

401. Id. § 30600(a), (c).Google Scholar

402. Id. § 30603(a).Google Scholar

403. Id. § 30603(b).Google Scholar

404. Id. §§ 30502, 30502.5. By late 1978, no “sensitive coastal resource” areas had been designated. Douglas telephone interview, supra note 383.Google Scholar

405. Id. § 30502.5. (Commission recommendation places the area in the “sensitive coastal resource area category for no more than two years.” To remain in that category, the area must be designated by statute.)Google Scholar

406. Id. § 30621.Google Scholar

407. Id. § 30801. “[A]n ‘aggrieved person’ means any person who, in person or through a representative, appeared at a public hearing of the commission, regional commission, local government, or port governing body in connection with the decision or action appealed, or who, by other appropriate means prior to a hearing, informed the commission, regional commission, local government, or port governing body of the nature of his concerns or who for good cause was unable to do either. ‘Aggrieved person’ includes the applicant for a permit and, in the case of an approval of a local coastal program, the local government involved.” Id. Google Scholar

408. Id. § 30310.Google Scholar

409. Id. § 30301.5.Google Scholar

410. Id. § 30301(d), (e).Google Scholar

411. Id. § 30312(b).Google Scholar

412. Id. § 30312(a).Google Scholar

413. Id. § 30310(b).Google Scholar

414. State Coastal Conservancy, §§ 31000-31406 (West 1977). Peter Douglas drew attention to the “great potential” of the coastal conservancy, “including its power to aggregate inappropriately subdivided lots,” which the conservancy will implement on a “voluntary” basis, i.e., through “negotiated sales.” Douglas telephone interview, supra note 383.Google Scholar

415. In addition to the institutional effects discussed at notes 132-50 supra and text at same, Peter Douglas emphasized how implementation of the coastal acts has affected state agencies and local governments. “There is greater sensitivity to transjurisdictional impacts. State agencies recognize the coastal agency as a permanent arm of state government.” Consequently, Douglas believes, it is now “much more likely that the delegation back to local governments will work.” Douglas telephone interview, supra note 383.Google Scholar

416. See notes 41-102 supra and text at same.Google Scholar

417. See notes 97-128 supra and text at same.Google Scholar

418. See notes 124-28 supra and text at same.Google Scholar

419. Joseph Bodovitz explained, plausibly, that it was “unrealistic to expect a lay commission [with its limited understanding of procedural rules] to conduct such a hearing,” not to mention the “amount of commission time” that such hearings would have absorbed. Bodovitz believed that if an applicant felt such a procedure was necessary, the proper alternative was adjudication “in the courts.” Bodovitz telephone interview, supra note 97.Google Scholar

420. ali code § 8-205 and note at 325-26. I shall discuss Florida’s experience with this process in the next article in this series.Google Scholar

421. See notes 65-69 supra and text at same.Google Scholar

422. See notes 69-96 supra and text at same.Google Scholar

423. See notes 157-62 supra and text at same. Peter Douglas suggested that it is unclear “whether lands decreased in value or simply stayed the same.” Both Douglas and Joseph Bodovitz argued that the “decrease” in Bodovitz’s words, may simply have been the “squeezing out of the speculative value.” Douglas telephone interview, supra note 383, and Bodovitz telephone interview, supra note 97.Google Scholar

424. See note 211 supra. Proposition 13, Peter Douglas believed, is “affecting planning in a negative way.” Douglas believed that the present trend “will have a significant impact on agencies’ ability to carry out state programs.” He noted that on Nov. 8, 1978, the day after Governor Brown’s reelection, the governor directed that each agency make a “10 percent reduction in its proposed budget.” Also, he reported that Paul Gann, one of the co-sponsors of Proposition 13, has proposed a new initiative that would place a “limit on state and local government spending, keyed to the consumer price index.”Google Scholar

425. See notes 170-92 supra and text at same.Google Scholar

426. Bodovitz telephone interview, supra note 97. See also notes 387-88 supra and text at same.Google Scholar

427. See notes 191-92 supra and text at same.Google Scholar

428. There was a conflict, Joseph Bodovitz explained, between the “yacht owners and the commercial fishermen” as to the effects of additional recreational boat use. Bodovitz telephone interview, supra note 97.Google Scholar

429. See notes 387-88 supra and text at same.Google Scholar

430. Frazier telephone interview, supra note 170.Google Scholar

431. Supra note 70, at §§ 7-201 to -208.Google Scholar