Introduction

For more than two decades, the call of gerontologists to integrate diversity in studies on older people has persisted (see Harper and Laws, Reference Harper and Laws1995; Calasanti, Reference Calasanti1996; McMullin, Reference McMullin2000; Enßle and Helbrecht, Reference Enßle and Helbrecht2018). This attempt in academia reflects ongoing trends in Western societies where the emergence of complex migration patterns, the differentiation of gender roles and sexual orientation, the growing gap between social classes, and increasing individualisation lead to social and cultural diversification that affect people of all ages – also in retirement age. Yet to date, only a small but growing number of scholars have followed the call for more research on diversity in later life, resulting in promising conceptual and empirical work (e.g. Pain et al., Reference Pain, Mowl and Talbot2000; Calasanti and Slevin, Reference Calasanti and Slevin2006; Calasanti et al., Reference Calasanti, Slevin and King2006; Denninger and Schütze, Reference Denninger and Schütze2017; Cela and Bettin, Reference Cela and Bettin2018; Oliver et al., Reference Oliver, Blythe and Roe2018; Sampaio et al., Reference Sampaio, King and Walsh2018). Nevertheless, a large share of current studies is still dedicated to the ageing experience and living situation of one ‘special’ group, such as women, migrants or non-heterosexual elders, rather than addressing diversity in old age on a conceptual level or from an intersectional perspective (Calasanti, Reference Calasanti1996). What Toni Calasanti (Reference Calasanti1996) stated more than 20 years ago still holds true, today: we seriously lack a conceptual debate on the diversity of older people in social gerontology and demography, likewise. Although the diversity of older people is in general increasingly acknowledged in research and society, it remains a vague term, hardly underpinned by consistent empirical evidence and conceptual analysis.

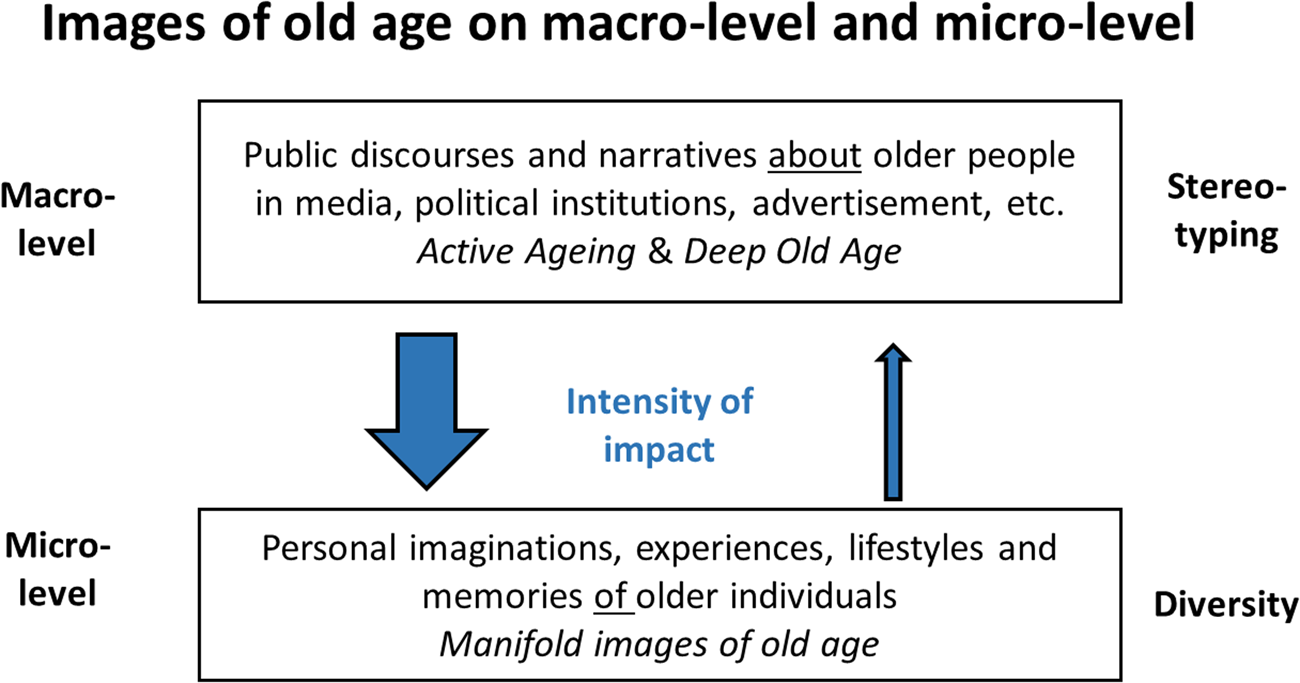

This article aims to enhance the conceptual debate on diversity in later life by suggesting a fresh methodology. We argue that it is through the exploration of changing images of old age that we can gain deeper understanding of the growing forms of diversity of old age. Empirically scrutinising newly emerging images of old age helps us to dismantle monolithic stereotypes about ‘the elders’ that frame much of the public discourse. The term diversity denotes various criteria of difference such as, for example, gender, sexual orientation, class, ethnicity, age, (dis-)ability, and their complex and often power-laden interplay. However, in this paper, we primarily focus on cultural aspects of diversity that impact ways of living and imaginations of later life. We address images of old age basically on two different scales: first, public discourses and narratives, and second, personal experiences and lived imaginations. To differentiate between these scales seems important, because it is mainly through images of old age in public discourses and narratives on the macro-level that banal stereotypes about ‘the elders’ prevail and disperse. Whereas in empirically scrutinised, personal imaginations and experiences of older individuals on the micro-level fresh new ways of living through old age and being and becoming elderly emerge (see Figure 1). Therefore, we argue that it is through the analysis of images of old age on the micro-level in a diverse society that the meaning of the empty signifier-like term ‘diversity in later life’ can be unravelled. By empirically exploring how imaginations, experiences and lifestyles of old age emerge, qualitative research enables us to investigate further what diversity in later life consists of, and how diversity simultaneously fosters the genesis of new images of later life. These new images indicate age-specific ways of diversity, based on, for example biographical experiences or linguistic belonging, and thereto related practices regarding how older people live diversity and why they search for differentiation.

Figure 1. Images of old age on the macro-level and micro-level.

To illustrate our argument, we present new images of old age from our qualitative empirical research in Berlin (Germany) that differ from well-rehearsed discourses on old age in media, advertisement and welfare state debates. Currently, two stereotypical images, ‘active ageing’ and ‘frail and dependent elders’, dominate much public discourse on old age. Yet, against the backdrop of an increasingly diverse older population, our article asks further why these two images prevail and outshine alternative narratives and lived counter-discourses. By contrasting the two prominent narratives on later life on the macro-level with personal imaginations and perceptions of later life on the micro-level from our empirical research, we seek to explore the power relations and hegemonial structures that keep only two narratives dominant and visible. Even though the diversity of older people creates manifold images of old age, they remain unheard and hardly enter into public discourses (see Figure 1).

The images of old age that we present from our empirical research arise from the micro-level of older people's individual experiences, imaginations and lifestyles of later life. Our examples address both the diversity and the heterogeneity of older individuals (Calasanti, Reference Calasanti1996), and thereby engage with diversity from the perspective of social groups within the older generation (diversity) and the individuality of every single older person (heterogeneity). In the following, we aggregate these small-scale notions as ideal types of images of old age, modelled after Max Weber (Reference Weber1922). Thus, they do not represent reality but are idealisations that help to express concisely the specificity of alternative images of old age. The following chapter introduces the term ‘images of old age’ and shows that the prevailing discourses fail to address the manifold imaginations of later life in a diverse society.

Implications of diversity for images of old age

A considerable body of research in social gerontology is dedicated to images of old age. Made of imaginations and valuations of later life, these images function as tools of communication, interpretative patterns and social practices (Göckenjan, Reference Göckenjan2000: 15). Hence, they express what individuals as well as society ascribe to old age. As tools of communication, these images reveal how later life is negotiated and valued on a personal and societal level, likewise. As social practices, images of old age display how people experience and cope with getting older and being old. Images of old age are socially constructed; hence, they are neither given nor fixed but change over time and with geographical and socio-cultural contexts (Achenbaum, Reference Achenbaum, Featherstone and Wernick1995; Göckenjan, Reference Göckenjan2000). A variety of images of ‘the elders’ exists: be it the older generation as drivers of the disaster scenario of demographic change, older people as valuable resources for engagement in community care and volunteer work, seniors as a promising consumer group for advertisement and media, or old age as a dreadful stage of life characterised by dependency and illness. All these narratives are more than mere imaginations. When entering public discourse, they have performative effects and translate into actions on various scales, such as attitudes and behaviour towards older people, the quality of intergenerational relationships, the self-image in retirement age that influences capacities and constraints (Bai, Reference Bai2014), and political programmes and funding (Amrhein and Backes, Reference Amrhein and Backes2007).

The rootedness of images of old age in time, place and specific socio-cultural contexts suggests that with growing socio-cultural diversification of the older generation, new notions of being and getting old should arise. Yet, to date, public discourses on later life barely reflect the increasing diversity. Although today's public discourses on old age are more differentiated and diverse than earlier conceptualisations (Kruse and Schmitt, Reference Kruse and Schmitt2005), only two strong narratives prevail in the public sphere: the discourse on ‘active ageing’, on the one hand, and on ‘deep old age’, on the other hand (van Dyk, Reference van Dyk2016; Montemurro and Chewning, Reference Montemurro and Chewning2018). These two stereotypical narratives clearly resonate with what Cole (Reference Cole1992) termed ‘bipolar ageism’: since the 19th century, images of old age have been split into negative and positive poles that comprise a positive extreme of health, virtue and self-reliance, and a negative counterpart of sickness, dependency and death. As these discourses are constantly repeated in media, advertisement and the public arena, these two poles determine to a large degree negotiations and valuation of later life on the macro-level – and in succession thoroughly infiltrate the micro-level of individual conduct in later life. We briefly outline some of the two pole's key features below.

Best agers and successful agers

The prominent positive image of people in retirement age pictures them as active and self-confident. Various (euphoric) terms such as best agers, golden agers or successful agers support this notion (McHugh, Reference McHugh2003). The paradigm of active ageing arose as a counter-model to the disengagement theory that equates the end of working life with social and political exclusion, leading to the conception of older people as inactive and passive (Cumming and Henry, Reference Cumming and Henry1961; Townsend, Reference Townsend1981). Against this backdrop, the narrative of old age as an active stage of life promises to return agency to older people. Political rhetoric and public discourses take up this narrative and utilise the ideal of an active retirement life as a coping strategy to manage the (especially from the perspective of the welfare state) troubling effects of demographic change (e.g. Walker, Reference Walker2002; World Health Organization, 2002; Walker and Maltby, Reference Walker and Maltby2012; Thomas and Applebaum, Reference Thomas and Applebaum2015). The prevailing view emphasises the potential of active elders in society as, for example, experienced workers (Kruse and Schmitt, Reference Kruse and Schmitt2005), precious volunteers and social carers (Lie et al., Reference Lie, Baines and Wheelock2009), or as a large and constantly growing group of consumers (Sawchuk, Reference Sawchuk, Featherstone and Wernick1995; Ylänne-McEwen, Reference Ylänne-McEwen2000). The predominance of ‘active ageing’ as the successful way to get older affects political and societal debates and becomes manifest in the self-perception of older people (Pain et al., Reference Pain, Mowl and Talbot2000; McHugh, Reference McHugh2007). Striving to delay ageing – or failing to do so – has become a self-responsibility that depends on strength of character and proper attention to youthful appearance (Mowl et al., Reference Mowl, Pain and Talbot2000). This self-responsibility to stay independent up to very old age is rooted in growing tendencies of neoliberalism (see e.g. Neilson, Reference Neilson2006; Vincent, Reference Vincent2006; Amrhein and Backes, Reference Amrhein and Backes2007; Katz and Calasanti, Reference Katz and Calasanti2014; van Dyk, Reference van Dyk2014). The constant repetition of the great health status and high level of activity of today's older people compared with earlier generations renders it less and less acceptable not to be part of this active group.

Declining bodies and dependent elders

The opposite pole on the macro-level comprises discourses on so-called ‘deep old age’ (Twigg, Reference Twigg2004: 62). It serves as a negative counterpart to images of active ageing. Especially unpleasant and disturbing aspects of ageing are banished into this stage of life (van Dyk, Reference van Dyk2015). As Julia Twigg (Reference Twigg2004: 64) aptly remarked, bodily decline in old age is at the centre of these discourses: ‘the Fourth Age can seem to be not just about the body, but nothing but the body. It dominates subjective experience, to the extent that it swamps all other factors in determining matters like morale or wellbeing’. It is not chronological age that determines who is considered ‘really old’ but the physical and mental conditions, the degree of social integration or the scope of daily activities. Research on the ‘Fourth Age’ reflects this notion and focuses on questions of care, decay and dependency in old age (see Milligan, Reference Milligan2009). The reduced action range is most prominently reflected in the large share of research on ‘ageing in place’ (see e.g. Rubinstein, Reference Rubinstein1989; Oswald et al., Reference Oswald, Wahl, Schilling, Nygren, Fänge, Sixsmith, Sixsmith, Széman, Tomsone and Iwarsson2007; Wiles et al., Reference Wiles, Leibing, Guberman, Reeve and Allen2012). The negative connotation of later life with dependency, decline and loss results in a widespread reluctance to be part of ‘the elders’ – who wants to be old if this means only bereavement? Hence, the fear of getting old dominates much of this discourse; and from the perspective of the subject, it is always the others who are conceived of as old (Pain et al., Reference Pain, Mowl and Talbot2000).

Thinking beyond the hegemonial discourses on old age

‘Bipolar ageism’ (Cole, Reference Cole1992) clearly creates a judgemental dualism that praises activity and social engagement and, at the same time, condemns the acceptance of ageing processes with their unpleasant aspects, likewise. This polarisation hardly offers any room for alternative means of ageing and grey areas between the poles: ‘If populations are homogenized as either successful or unsuccessful agers, then the diversity of the aging experience is flattened, especially the consequences of social inequalities as they intersect with age relations’ (Katz and Calasanti, Reference Katz and Calasanti2014: 29). As more and more people with differential backgrounds live into old age, the prevailing dualism on the macro-level is rendered questionable in many regards by the lived ageing experiences of individuals: Which image matches people with lifelong disabilities and bodily constraints? Does their bodily condition outshine all other factors and render them dependent older people from the start? Also, when considering people with a migrant history, the two poles seem fairly limited. Neither of the two images speaks to the cultural diversity of transnationalism and to the fact that people bring various – and often differing – images of getting and being old with them. How does, for example, the imagination of an older person as transmitter of knowledge or respectable head of family that we encountered in our empirical data fit the dualism?

In principle, the multiplicity of ageing experiences would suggest a diversification of images of old age also on the macro-level. However, the polarisation of images of old age in public discourse seems to prevail, though they offer no alternatives that correspond with the lived diversity of older people, nor can they account for age-specific factors that foster diversity in later life. We propose three explanations for this disparity. First, the actors who transmit images affect visibility. Powerful actors, such as the advertisement industry, media and political institutions mainly disseminate the two dominant images. These actors have the means to access communication channels and propagate the benefits of active ageing while talking about ‘the elders’ without being part of this group. The underlying rationale that fosters ‘active ageing’ as opposed to frailty and decline is based on economic and political reasons, such as revenues for the advertisement industry by selling anti-ageing products (Neilson, Reference Neilson2006; Petersen, Reference Petersen2018), the reduction of costs for caring systems as well as the social costs of demographic change (Thomas and Applebaum, Reference Thomas and Applebaum2015; Wang, Reference Wang2019). The transmitters of diverse, alternative images of old age, however, are more fragmented and have less access to communication channels. In our research, it was apparent that the small initiatives, or even individuals, who live according to alternative images, still have to sort out who has the right and responsibility to speak about the group of which they are part. Additionally, the diverse images rather stem from cultural factors and differing ways of living. In the current neoliberal rationale, it is much harder to draw attention to culturally related matters compared to economic issues. We see a second reason for the insufficient representation of diverse images in public discourses in the institutionalisation of images. ‘Active ageing’ is visible in advertisements, slogans and products that call upon older people to fight frailty and decline in later life (Petersen, Reference Petersen2018; MacGregor et al., Reference MacGregor, Petersen and Parker2018), as well as in political programmes that urge older people to actively engage in volunteer work to mitigate the effects of, for example, demographic change (Hank and Erlinghagen, Reference Hank and Erlinghagen2010). However, alternative images of old age still have to undergo the process of institutionalisation. Individual actors and minority initiatives have to incorporate diverse experiences and imaginations to then jointly develop a common strategy of communication, assign an institution to represent the image and catch attention. Each of these steps is slow, laborious and requires a certain level of organisation. A third reason could lie in the challenge to communicate complexity. The simplification and reduction that is inherent in the two dominant images helps to disseminate strong, banal, generalising narratives. However, it is much harder to communicate the complexity rooted in the diverse images. Aside from the simple fact that there is a richness of images of old age, it remains a challenge how to formulate a shared image while at the same time accounting for the diversity of living experiences that make up these images.

Against this backdrop, the aim of our paper is twofold: we explore lesser-known imaginations of later life that exist on the micro-level to (a) unravel diversity of old age by tracing the genesis of diverse and contingent images of old age that arise from individual's imaginations and experience of later life and to (b) make diverse images visible and heard in macro-level public discourses. Drawing on empirical research, we demonstrate how analysing the formation of an image of old age renders visible the intertwined factors that comprise diversity in later life.

Research methods

Our empirical findings are based on an interdisciplinary research project on super-diversity (Vertovec, Reference Vertovec2007) and ageing in Berlin (Germany), carried out from 2017 to 2020. The study aims to understand the nexus between super-diversity and ageing in an urban environment. The findings presented here are the result of the project's qualitative exploration of age and diversity, based on expert interviews and focus group discussions. All interviews were conducted in German, and quotes have been translated into English by the authors.

Our research started with 18 expert interviews with representatives from counselling centres, social meeting places and initiatives for elders. To reflect the largest possible diversity in our findings, we carefully selected interviewees working with clientele with different backgrounds in terms of ethnicity and migrant history, social class, gender, sexual orientation and bodily ability. The interviews followed an open approach and comprised questions on leisure activities, housing conditions, challenges of the ageing process, social networks, and the influence of parameters of difference such as gender, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, (dis-)ability and social class on the ageing experience. We analysed the interviews by following Mayring's (Reference Mayring2000) approach of qualitative content analysis with the support of the software management program MAXQDA. Six main codings were pre-set as we started the analysis: (a) support systems, (b) challenges in later life, (c) intersectional experiences, (d) housing in later life, (e) the role of spaces and places, and (f) images of old age. Furthermore, we developed the seventh main coding, ‘governing age(ing)’, during the analysis. In order to link expert knowledge with everyday life experiences, we discussed main findings from the first research phase in four focus groups. Again, we strived to represent the diversity of people in retirement age and were careful to select a diverse mix of discussants. The 26 discussants in our four focus groups comprised an age range from 60 to 92 years, had different social and ethnic backgrounds, and differed in their ties to family and friends, bodily ability, gender and housing situation. Of our 26 participants in the focus groups, 19 were female and eight male, which results in a possible bias of more female voices in our research.

During focus group discussions, we presented the four main hypotheses from the expert interviews to the participants ((a) diversification of images of later life; (b) homogenisation regarding housing needs and worries about health and care systems; (c) decreasing familial support; and (d) future challenges for older people in Berlin) and collected their opinions and thoughts on these statements.

To draw joint conclusions from the focus groups and the expert interviews, we undertook a second phase of data analysis in a team of four researchers that allowed an intersubjective process of hypothesis-building. The analysis revealed that the diversity of older people varied in importance depending on the topic of interest. For instance, all interviewees and discussants – regardless of their background – named health concerns, loneliness and scarce financial resources as the main challenges in old age. For other matters, biographical experiences and socio-cultural imprints were of great importance. Imaginations, narratives and images of later life are thematic fields where the impact of diversity is striking. In what follows, we first give insights into the variety of imaginations of later life that came up in our research. Second, we take a closer look at three images from our empirical research to unravel how the diversity of the older generation and new images of old age interrelate.

Diversity in images of old age

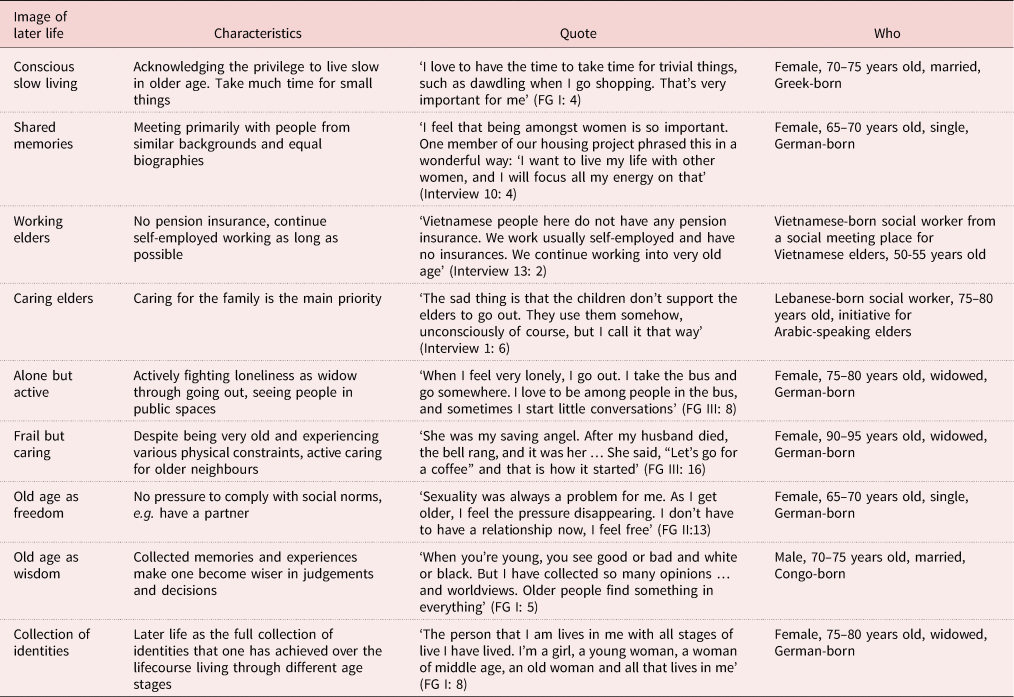

Our interviewees held various images of later life that cut across and challenge the two poles of active ageing and old age as decline (see Table 1). Of course, the dominant narratives of active ageing and old age as decline were also present. Engaging in volunteer work and giving something back to society was the main reason for one male discussant to finally retire at the age of 70 (focus group (FG) I: 6). A female participant adds, ‘We should stay active … I do not want to grow old’ (FG I: 7), a quote that highlights the pressure that the prevalence of active ageing exerts. Old age as decline was mentioned as physical constraints increase, partners and friends die, and life gets lonelier. Frightening stories about friends and family members reinforce the negative picture about the last stage of life. The caring crisis, fear of care technology such as care robots, and worries of becoming unable to care for oneself dominate the narrations. However, between the lines, we find alternative images that go beyond active ageing, enlarge the meaning of old age as decline and open new perspectives on later life.

Table 1. Alternative images of old age

Beyond active ageing

For many of our participants, later life is filled with activities. However, that does not necessarily resemble the image of active ageing. One of our focus group discussants, for instance, mentions the privilege to do things slowly in later life. She appreciates that now she has the time to do her things slowly and take more time compared to her earlier life, where she had been working in a funeral service for the Greek community. Old age for her is ‘slow living’ (FG I). Appreciating time and take the freedom to do things slowly is hardly a matter in debates on active ageing. Another alternative image is held by elders who strive for activities with people who have similar backgrounds and biographies. When engaging in initiatives, they strive to create a common identity with others through ‘Shared memories’ (Interview 10). So far, the motivation to engage in activities in later life has been more related to staying healthy and ‘young’ or altruistic goals than to meet like-minded people (see Principi et al., Reference Principi, Chiatti and Lamura2012). Quite different from ‘active ageing’ through physical activity and the engagement in volunteer work is the situation of people without pension insurance, e.g. older members of the Vietnamese community. A social worker for the Vietnamese community reports that many of her clients earlier missed taking care of their insurance. Lacking other resources, those elders have to keep on working in small shops and family restaurants as long as possible (Interview 13). A further image that stretches the definition of active ageing is the image of ‘Caring elders’ that primarily arises in transnational families. Older people who engage in care work within their families and place a priority on their role as grandparents are the carriers of this image (Interview 1). They are active in their daily lives, but primarily in the private sphere without any visibility.

Beyond old age as decline

We met older women through our research who, at first glance, fit well into the image of old age as decline. They suffer from physical constraints, had experienced the deaths of their partners and report suffering from loneliness frequently. However, despite these constraints, they continue to engage with life and keep on caring – for themselves and for others. One woman, for example, regularly leaves her home when she starts to feel lonely. She searches for places of encounter within the city, takes the bus to be among people and goes out for lunch, even alone, to experience the liveliness of the city (FG III). She is ‘alone, but active’. Another woman, aged over 90 years and in need of support with some tasks of everyday life, continues to be attentive to her neighbours. When her neighbour's husband died, she realised the neighbour's crisis and took her out for coffee (FG III). Despite her frailty and great age, she continues to care for others. Both examples lie at the intersection of the two seemingly opposite poles of active ageing and old age as decline. By this, they challenge the assumption that very old, frail people are primarily dependent on others, as they actively engage with life and act supportive.

Ageing as intellectual development

Three other images from our research refer to the intellectual development that participants experienced when they became older. One woman reflects on how advancing in age relieves her from the pressure of social norms. For her, the social norm to live in a partnership has been a severe burden throughout her life. It is only now, in her seventies, that she feels relieved from the pressure of establishing a relationship. She experiences ‘Old age as freedom’ as she feels free to stay on her own and conduct her life the way she wants it (FG II). Another participant recounts that with increasing age he has become wiser and more thoughtful. As a young person, judgements were easily made, but as he gets older, things become less black and white, but grey due to his lived experiences and collected memories. He seems content with becoming older as he experiences ‘Old age as wisdom’ and a stage of life for reflection (FG I). We made a similar observation in the image ‘Collection of identities’. A 78-year-old women describes that for her, being an older person means being aware of and incorporating all stages of life that she has lived so far. According to her, her personality in old age is made of the little girl, the young woman, the middle-aged woman she used to be as well as the older woman she is today (FG I).

Unravelling diversity and heterogeneity through images of old age

After this insight into the wide array of images of old age that we collected in our research, we take the example of three images – ‘Caring elders’, ‘Shared memories’ and ‘Collection of identities’ – to explore further the interrelation of diversity and images of old age. The images ‘Caring elders’ and ‘Shared memories’ refer to the diversity of social groups within the older generation, while ‘Collection of identities’ speaks more to the heterogeneity of the older generation and the individuality of every older person.

Diversity-related images of later life: ‘Caring elders’

The image ‘Caring elders’ arises from diversity in lived experiences of later life, notably in terms of migrant experiences. Imaginations and personal conduct surrounding this image are characterised by a strong influence of expectations of the social and familial surrounding regarding grandchildren care and familial support. Although the expectation to engage in volunteer caring activities is present in the discourse on active ageing (van Dyk, Reference van Dyk, Denninger and Schütze2017), social demands regarding care activities within the private, familial sphere seem to have become less visible. We noticed this shift in our research in terms of different attitudes towards care activities within the family. On the one hand, elders, especially well-educated and German-born elders, widely agreed that although family is important in later life, it is only one important matter among others:

The family plays an important role, but how to say, I'm on two tracks. I have many friends and groups that are important to me … and travelling. I would never accept my family making demands! I work with a calendar. They call and say, ‘Can you watch the kids?’, it is kind of regularly, on Thursdays and sometimes on weekends, but apart from that, they know that I don't have time. (Male, FG II: 10)

The discussant stresses his agency to decide how to spend his time. He feels no obligation to meet the expectations of his family. His family is important to him, but not exclusively. This opinion was widely agreed on in other focus groups by male and female participants (FG I; FG IV), where volunteering for the community and cultural activities in retirement were highlighted as a privilege, but also an obligation to contribute to society (FG IV: 4). The discussants agreed that ‘We don't have time! We are fully booked!’ (female, FG IV: 4). In this regard, they meet the expectations of active ageing in staying active and engaged with social life.

On the other hand, however, active ageing did not match the reality of other interviewees. Role-taking as grandparents, especially as a grandmother, was described as playing the key role for some:

They [the Arab elders] have no occupation except for caring for their grandchildren and helping with the housework … The sad thing is that the children don't support the elders to go out. They use them somehow, unconsciously of course, but I call it that way. They prefer their mother being at home and watching the grandchildren. It's very convenient for them. But then, the elders do not go out and they don't get any support to do so. So, they feel old, but they are not old at all. A woman becomes grandma before she turns 50. And grandma means old, no matter how old you are. (Representative of an Arab culture association, Interview 1: 6)

The quote shows that becoming a grandmother can be the determining role in later life. Becoming a grandmother can, due to cultural practices, define when women start to be old, where women spend the main part of their later life – because watching children occurs mostly in private spaces – and how everyday life is organised. Our findings suggest that the image ‘Caring elders’ occurs, in particular, in ethnically diverse societies among female elders with migrant history. It evolves from cultural values and practices that are influenced by the ties older migrants sustain with their country of origin and the transnational, globalised world in which they age (Torres, Reference Torres and Phellas2013).

The genesis of ‘Caring elders’

Living (and ageing) in transnationality implies a dual orientation in individual experiences and social practices. The negotiation of here and there affects cultural and social practices, including intergenerational relations (Vertovec, Reference Vertovec2004). The social networks in people's country of origin formed a key point of reference in the imagination of old age throughout our research. This is especially true for older people who live in circular migration regimes such as former guest workers from Turkey in Germany, a finding that earlier studies support (see Strumpen, Reference Strumpen, Baykara-Krumme, Motel-Klingebiel and Schimany2012; Rohstock, Reference Rohstock2014). Another critical point of reference for thinking about being and becoming old are memories of later life of their parents and grandparents. Our focus group participants (FG I–IV) tended to compare themselves to the generation of their parents, and as the largest share of migrants in Germany aged 60 years and over are first-generation migrants (Nowossadeck et al., Reference Nowossadeck, Klaus, Romeu Gordo and Vogel2017), the memories they hold of their grandparents and parents reflect images of old age from various countries and cultures.

The memories people hold from and the ties they keep with their country of origin are as diverse as migrants are individuals, resulting in a fine differentiation of imaginations of old age. Our focus on diversity in later life urges us not to be content with the broad category ‘older migrant’. Older immigrants differ strongly in their biographies; and not everyone does, wants to or even can stay in touch with their country of origin – let alone obey the existing social roles over there. For example, the employee of a counselling service for former Turkish guest workers (Interview 2) reported that some of her female clients do not travel to their hometown to avoid confrontations with traditional gender roles. They oppose traditional images and social norms by reducing their transnational ties to a minimum. Even though there is a transnational migration of images of old age, images do not travel unchanged. They interact with individual living conditions, social and familial situations, and form new variations.

Age-specific diversity: ‘Shared memories’

The image ‘Shared memories’ reflects age-specific diversity and emerges out of everyday practices of older individuals. Its main characteristics are a strong desire to be among equals and to experience group identification. In its extreme forms, this striving is visible in so-called Retirement Cities, where active and wealthy elders form an exclusive settlement with inhabitants of the same age and socio-cultural background (McHugh, Reference McHugh2007; Oliver et al., Reference Oliver, Blythe and Roe2018). In these places, the coming together with like-minded people is a deliberate spatial strategy of inclusion through segregation and, as Oliver and O'Reilly (Reference Oliver and O'Reilly2010) showed in their research, is experienced by the inhabitants of these segregated settlements as an ordinary phenomenon. Notably, in spatially diverse environments like Berlin, striving for a shared identity also becomes an everyday practice.

Our research included various sites of leisure and volunteer work for older people: drama groups, cultural clubs, settings of political activity, clubs to play memory games and neighbourhood cafés. Our findings indicated that the motives behind the engagement at a certain place were strongly influenced by the desire to spend time with people who were somehow similar to oneself. The co-ordinator of a female-only housing project for older lesbians reports:

I feel that being amongst women is so important. One of the members of our housing project phrased this in a wonderful way: ‘I want to live my life with other women, and I will focus all my energy on that. I want to respond to the creativity of other women, take up their thoughts and lead my life in such a place.’ (Interview 10: 4)

A similar point was made by a self-organised housing project where mainly people with an involvement in the feminist movement and the 1968 revolution gather, and where the initiators assume similar attitudes and values of the future inhabitants (Interview 18). An organisation for older migrants with a Turkish background reported that their clients were reluctant to use public offers for elders but felt more comfortable in groups specifically organised for elders of one ethnic or linguistic community (Interview 2).

The genesis of ‘Shared memories’

These examples stress the desire to be among ‘similar’ people in later life and relate to the phenomenon of homophily in social networks that has been stated by others before (see McPherson et al., Reference McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook2001; Brashears, Reference Brashears2008; Oliver and O'Reilly, Reference Oliver and O'Reilly2010; Oliver et al., Reference Oliver, Blythe and Roe2018). However, our findings go beyond that and suggest that homophily in later life differs from the striving for homogeneity in other lifestages because specific age-related factors explain why and how the desire to be among equals emerges.

First, the wish for a shared identity is related to the desire to meet other elders of the same mother tongue. Migrant associations in our study attributed segregation by language to old age and considered the wish to stay in one's own language community as a key factor regarding why older migrants refrain from using (generic) municipal counselling or engaging in activities for elders (Interview 1). The declining ability and willingness to communicate in a foreign language is reasoned by old age. The interviewee stresses a difference between ‘the active life’ and older age, where the early experiences of a person's childhood gain importance. Of course, this diagnosis does not apply to all elders, but the finding shows how the desire to be among people who speak the same mother tongue is justified. Along with a growing diversity of older people with migrant histories, the plurality of languages increases, and consequently, this might foster the emergence of a manifold, fine separation based on language.

A second age-related factor is the desire to meet people with similar biographies. In very different contexts, participants told us about the longing to exchange memories with elders who have experienced similar situations throughout their life: for elders with a migrant history – be it as guest worker, student or refugee – the exchange about leaving one place and moving to another place is important; for people who have spent a great share of their life in East Berlin, it is crucial to talk about memories of the German Democratic Republic; for elders involved in the feminist and liberation movement of 1968, they are glad to share their experiences and life story with like-minded people, and for older gays and lesbians, it is the wish to meet people who know the challenges and threats of the coming-out process (for the experience of older gays and lesbians, see also Marhánková, Reference Marhánková2019). For some, the lived experiences manifest in songs, stories and dishes. Russian singing clubs, Polish cooking circles and the storytelling group of elders within the African community are some examples of how shared memories bring people together and foster feelings of belonging that are difficult to create among people who do not share a similar biography. Our findings do not diminish the importance of shared interests and common goals in establishing meaningful contacts between people (see Amin, Reference Amin2002; Dirksmeier and Helbrecht, Reference Dirksmeier and Helbrecht2010; Dirksmeier et al., Reference Dirksmeier, Helbrecht and Mackrodt2014), but add shared memories as another layer to the complex process of group building. ‘Shared memories’ presents old age as a stage of life where group identification is critical and the desire to be among equals is high. This neither responds to discourses of active ageing nor to discourses of deep old age and bodily decline. Instead, the roots of this image are in the diversity of older people, and this diversity generates new, diverse images of later life. The accentuation of individuality and life paths among the older generations creates complex patterns of diversity and fosters increasing differentiation.

Biographical images of later life: ‘Collection of identities’

The third image, ‘Collection of identities’, illustrates how individual experiences and personal traits impact imaginations and ways of living in old age. G, a 78-year-old woman, speaks about her identity in older age as a multi-layered personality. It carries all identities she has lived before. She perceives the little girl, the young woman, the middle-aged woman and the woman of older age she is today as equally important components of her identity. In her eyes, this collection of identities is what distinguishes older people from younger people:

I've been in a meeting with younger people and I've told them: do you know what fundamentally distinguishes you from us? We older people, we know what it is like to be young. But you, the Young, you have no idea what it means to be old, and if you want to know it, you have to come and talk to us. (FG I: 8)

In her perception, having lived through different stages of life renders older people capable of understanding younger people. Young and middle-aged people, however, do not know what it is like to be old and instead draw on stereotypes about the older generation when talking about ‘the elders’ (FG I).

The genesis of ‘Collection of identities’

‘Collection of identities’ relies on the individual life stories of older people and thus refers to the heterogeneity of the older generation. In what could be considered an initial call for the integration of diversity in ageing studies, Calasanti (Reference Calasanti1996) distinguished between the heterogeneity and the diversity of the older generation. While diversity speaks to a differentiation between groups of older people, the concept of heterogeneity refers to the differences between older individuals. In contrast to ‘Caring elders’ and ‘Shared memories’ that we framed in social groups within the older generation, ‘Collection of identities’ is concerned with the personal situation of every older person. Greater political and social circumstances as well as individual characteristics influence how people have experienced being a child, a younger person or a middle-aged person. In one of the focus groups, the participants discussed how the framing of the Second World War that meant growing up without a father and a constant lack of resources shaped their childhood. Still, they agreed that personal traits, such as the character, attitudes towards life and individual chances equally impacted their experience of lifestages (FG I). As they grow older, they have collected experiences, lived lifetime, and different roles and identities. This collection of memories makes up the rich biographical experiences that distinguish older people from middle-aged and young people, and has made them who they are (Andrews, Reference Andrews1999).

Against the backdrop of our research on super-diversity and old age, we want to stress the value of a dual perspective on diversity and heterogeneity in later life. While social groups help to identify and analyse variations in images of later life that occur due to structural differences and shared life paths, looking on the individuality of older people as the heterogeneity approach allows sheds light on individual identities that might cut through and alter pre-cast groups. In our view, applying both perspectives on diversity is a first step to doing justice to the individual differences felt and experienced by older individuals.

Conclusion

Understanding the growing diversity of older people is a key challenge for ageing studies (and society). In this paper, we have suggested a fresh methodology in order to unravel the meaning of ‘diversity in later life’. We have argued that the analysis of images of old age on the micro-level of individuals and social groups offers a fruitful lens through which diversity in old age becomes visible. Through qualitative empirical research, we explored the interrelations between images of old age and the growing diversity of older people. The results of our empirical research in Berlin are in stark contrast to discourses about old age on the macro-level of Western societies. Here, currently two images – active ageing and later life as dependency and decline – dominate Western patterns of thought. This polarisation between either successful, healthy ageing or ageing as bereavement fundamentally shapes discourses on ageing and being old on the macro-level. However, this polarisation does not account at all for the diversity of ageing experiences and life plans on the micro-level among older people who differ in terms of gender, sexual orientation, age, social class, migrant history and individual life paths. Drawing on qualitative research on super-diversity and ageing in Berlin, we present alternative images of old age that challenge the polarisation of images on the macro-level. The paper demonstrates that through these alternative images of old age, we can trace how diversity in later life emerges, how age-specific ways of diversity foster manifold images of later life and how the heterogeneity of older people and their imaginations of later life arises from individual experiences of different lifestages. Based on our findings, we argue that by exploring the genesis of diverse images of old age, we can substantiate the vague concept of diversity in old age and, at the same time, make less-known images more visible in at least two ways:

First, our findings show that growing diversity is inherent in the formation of new images of old age. This phenomenon is obvious in the image ‘Caring elders’, which reveals the impact of diversity for the genesis of alternative images of old age. It evolves due to transnational ties that enable contact with imaginations and narratives of later life from abroad. Similarly, in the image ‘Shared memories’, it is the diversification of the people in retirement age that intensifies the formation of subtle group differentiation and patterns of belonging. The desire to communicate in one's mother tongue and to meet people with similar biographies and experiences that are apparent in our findings affect striving for homogeneity; in this study, both factors are related to older age. The image ‘Collected memories’ goes beyond social groups and stresses the importance of individual experiences and life paths for the formation of individual images of later life. Seeing both, the diversity as well as the heterogeneity of the older generation is a crucial point of our argument.

Second, we stress the value of images of old age as a methodological tool to unravel the meaning of the vague term ‘diversity in later life’. As diversity creates new images, any image is a possible point of reference to understand the dynamics and formations of diversity in old age. Prominent images such as ‘active ageing’ and ‘deep old age’ and lesser-known imaginations of later life are equally suitable for the analysis. How do people manage different images of old age? Why do they adjust or reject a certain image? What role do images of old age play if older people reject being part of the group ‘the elders’? Tracking these questions might reveal explanatory patterns in factors of diversity such as gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, religion or social class, and even more interestingly, at the intersection of these factors.

We conclude by urgently calling for more empirical and conceptual research, that holds the potential to actively stir public debates about images of later life. To challenge the current hegemony of grand narratives of later life, it is important to make counter-images visible and give voice to untold subject positions and stories. Yet, these counter-images barely exist – they have still to be explored, articulated and conceptualised, based on accountable research with an outreach component. Therefore, enabling alternative images to undercut and – more importantly – change public discourses could contribute to the long overdue public recognition of diversity in later life. It is only through the reflection of the manifold imaginations, experiences and lifestyles of older people in adequately complex and varied images of old age that the rich lived experiences of older individuals are represented and, thus, can blossom in diversity.

Data

Due to the wishes of our interviewees, supporting data are not openly available. For further information about the data and conditions for access, contact [email protected].

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to two student researchers, Carlotta Reh and Lisa Thiele, for their assistance and support in the analysis of the empirical data, and Dagmar Haase, Tobia Lakes and Hannah Haacke for their co-operation in the research project.

Financial support

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG, project number HE 2417/16-1). The funding source had no involvement in any stage of the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.