Introduction

Reflecting broader gaps in critical understandings of rural ageing (Scharf et al., Reference Scharf, Walsh, O'Shea, Shucksmith and Brown2016; Skinner and Winterton, Reference Skinner and Winterton2017), social exclusion amongst rural-dwelling older adults is under-theorised within gerontology and the wider social policy literature (Burholt and Dobbs, Reference Burholt and Dobbs2012). How exclusionary processes intersect with diverse patterns of rural ageing has received little attention in empirical study (just 19 studies according to a recent scoping review; Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Scharf and Keating2017), and less still within conceptual frameworks. Indeed, only two previous models have really engaged with this topic, with one formally conceptualising older adult exclusion in its rural context (Scharf and Bartlam, Reference Scharf, Bartlam and Keating2008) and the other focused on ‘connectivity’, and its barriers and facilitators, as a converse to exclusion for rural older people (Curry et al., Reference Curry, Burholt, Hennessy, Hennessy, Means and Burholt2014). More critically, the factors that mediate (i.e. protect against or intensify) exclusion for rural-dwelling older adults are not well understood in terms of everyday lived experiences, or as a set of conceptual relationships. Consequently, how rural living might function to disadvantage or protect older people remains largely an unanswered question.

There are linked concerns about whether or not place is simply a part of a rural older person's life where they are susceptible to exclusion; or, whether in its own right place functions as one of the mediators of exclusion, shaping different outcomes in multiple areas of life (Walsh, Reference Walsh, Skinner, Andrews and Cutchin2018). While place has emerged as an important sub-topic in social exclusion, a focus on urban settings has dominated (Van Regenmortel et al., Reference Van Regenmortel, De Donder, Dury, Smetcoren, De Witte and Verté2016). However, even here, gaps in conceptual understanding persist (Scharf et al., Reference Scharf, Phillipson and Smith2005; Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, De Donder, Phillipson, Dury, De Witte and Verte2013a; Buffel and Phillipson, Reference Buffel and Phillipson2018).

The challenge of unpacking the relationship between rurality, ageing and exclusion is compounded by the diverse lifecourse experiences of older populations and the heterogeneity of their rural contexts (Glasgow, Reference Glasgow1993; Keating, Reference Keating2008). Residential tenure, status variables (e.g. socio-economic position, gender, ethnicity), individual agency and lifecourse shifts in personal circumstances (e.g. retirement, ill-health) have the capacity to alter the potential for exclusion in later life (Scharf and Bartlam, Reference Scharf, Bartlam and Keating2008; Hennessy and Means, Reference Hennessy, Means and Walker2018). So too has the type of rural community in which older people live (Schulz-Nieswandt, Reference Schulz-Nieswandt, Walter and Altgeld2000; Scharf et al., Reference Scharf, Walsh, O'Shea, Shucksmith and Brown2016). There are different kinds of rural places, just as there are different kinds of rural older residents, e.g. a person could be ageing in a dispersed or remote rural community, or a near-urban, island or village community. The capacities of different rural settings, and the geographic and socio-economic characteristics of such settings, have the potential to support and/or hinder older adults (Hennessy et al., Reference Hennessy, Means and Burholt2014a; Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, O'Shea, Scharf and Shucksmith2014). Nevertheless, while the possibility for differentiated lifecourse trajectories and places to influence exclusion outcomes is clear, the extent to which this happens in people's daily lives has not been sufficiently conceptualised.

There is evidence to suggest why rural older people might be particularly susceptible to disadvantage. Lower population densities, migration outflows and changing social structure can conspire to challenge the connectedness of rural older individuals over their lifecourse (Walker et al., Reference Walker, Orpin, Baynes, Stratford, Boyer, Mahjouri, Patterson, Robinson and Carty2013; Burholt and Scharf, Reference Burholt and Scharf2014; Hennessy et al., Reference Hennessy, Means and Burholt2014a). Re-structuring of public services, together with an underdeveloped private market, can produce weakened services (Dwyer and Hardill, Reference Dwyer and Hardill2011; Skinner and Joseph, Reference Skinner and Joseph2011; Warburton et al., Reference Warburton, Cowan, Winterton and Hodgkin2014). The decline of resource sectors, such as agriculture, and the lack of economic diversification can mean higher levels of unemployment, challenges to fiscal stability and higher deprivation (Moffatt and Glasgow, Reference Moffatt and Glasgow2009; Milbourne and Doheny, Reference Milbourne and Doheny2012; Hanlon et al., Reference Hanlon, Skinner, Joseph, Ryser, Halseth, Skinner and Hanlon2016). Threaded through these realms of individual- and community-level exclusion is the susceptibility of rural settings to macro forces, including global economic trends, urbanisation and urban-centric policy (Giarchi, Reference Giarchi2006; Lovell et al., Reference Lovell, Gray, Boucher, Skinner and Hanlon2016). While global factors can potentially dilute the significance of local places for older people (Phillipson, Reference Phillipson2007), they can in a more moderate way underlie processes of change, resulting in a gradual dislocation of ageing individuals from rural settings over time (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, O'Shea, Scharf, Skinner and Hanlon2016). These mechanisms are such that old-age vulnerabilities can combine with forms of rural deprivation to produce a ‘double jeopardy’ for some rural dwellers (Krout, Reference Krout1986; Joseph and Cloutier-Fisher, Reference Joseph, Cloutier-Fisher, Andrews and Philips2005).

There is, of course, also evidence that testifies to older people's satisfaction with living in rural communities. This work goes beyond rural idyll stereotypes to provide a nuanced consideration of older adults’ relationship to place. Rural communities can be important sources of social opportunities, meaningful relationships and informal support (Wenger and Keating, Reference Wenger, Keating and Keating2008; Keating et al., Reference Keating, Eales and Phillips2013). Some rural settings can help to construct a sense of togetherness that reinforces local trust and reciprocity (Heenan, Reference Heenan2010; Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, O'Shea, Scharf and Shucksmith2014). In experiential terms, and as with other residential contexts, the relationship between older people and their rural places is largely subjective and can embody accumulated memories and a significant affirmation of self-identity (Rowles, Reference Rowles2008; Winterton and Warburton, Reference Winterton and Warburton2012; Walsh, Reference Walsh, Walsh, Carney and Ní Léime2015). Practices, whether social, cultural or agrarian, imbue important meanings of lifecourse community belonging (Eales et al., Reference Eales, Keefe, Keating and Keating2008; Wiles et al., Reference Wiles, Leibing, Guberman, Reeve and Allen2012; Burholt et al., Reference Burholt, Curry, Keating, Eales, Hennessy, Means and Burholt2014). Consequently, deep emotional attachments between people and places can emerge over time (Rubinstein and Parmalee, Reference Rubinstein, Parmelee, Altman and Low1992; Gustafson, Reference Gustafson2001).

The documented advantages and disadvantages of rural ageing across the lifecourse do not necessarily reflect opposing conclusions (Wenger, Reference Wenger2001), and often sit comfortably within the same studies. This illustrates the apparent juxtaposition of objective and subjective realities. A meaningful understanding of how meditating factors work to shape and intertwine such contrasting rural lived experiences is still largely absent from gerontology (Scharf et al., Reference Scharf, Walsh, O'Shea, Shucksmith and Brown2016). Ultimately, we lack both the necessary empirical insights and conceptual frame to unpack the complexity and potential disjuncture of growing older in rural places.

With the aim of advancing conceptual understanding on rural old-age social exclusion, this article explores how exclusion is manifest in the lifecourse experiences of rural-dwelling older adults and the role of mediating factors in the construction of exclusion in different kinds of rural places. To increase the explanatory power of current understandings, the article presents a conceptual framework of rural old-age exclusion based on empirical findings. The objective is not to problematise rural ageing, but to reflect its complexity, variability and capacity to yield both advantage and disadvantage. The analysis draws on case-study data from a cross-border qualitative study in Ireland and Northern Ireland (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, O'Shea and Scharf2012). This single island, dual jurisdiction provides a valuable context for the article. Agricultural reform, population processes and other socio-economic changes have combined to produce a pronounced rural ageing demographic structure in both settings. Fifteen per cent of the rural population in Ireland and 15 per cent in Northern Ireland are aged 65 years and over (compared to 12 and 15%, respectively, for the urban population). Representing some of the highest rates of older adult rural residency in western developed regions, 43 per cent of older people in Ireland and 33 per cent of older people in Northern Ireland live in rural areas (Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA), 2011; Central Statistics Office, 2016). Contrasting welfare models in the two jurisdictions, and historical sectarian activity in Northern Ireland, also offer an intriguing backdrop for this analysis.

Conceptualising rurality in old-age exclusion

For this article, we draw on a recent definition of old-age social exclusion that emphasises accepted features of exclusion such as multi-dimensionality, dynamism, relativity and agency, together with age-related aspects of disadvantage:

Old-age exclusion involves interchanges between multi-level risk factors, processes and outcomes. Varying in form and degree across the older adult life course, its complexity, impact and prevalence are amplified by old-age vulnerabilities, accumulated disadvantage for some groups, and constrained opportunities to ameliorate exclusion. Old-age exclusion leads to inequities in choice and control, resources and relationships, and power and rights in key domains of neighbourhood and community; services, amenities and mobility; material and financial resources; social relations; socio-cultural aspects of society; and civic participation. Old-age exclusion implicates states, societies, communities and individuals. (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Scharf and Keating2017: 93)

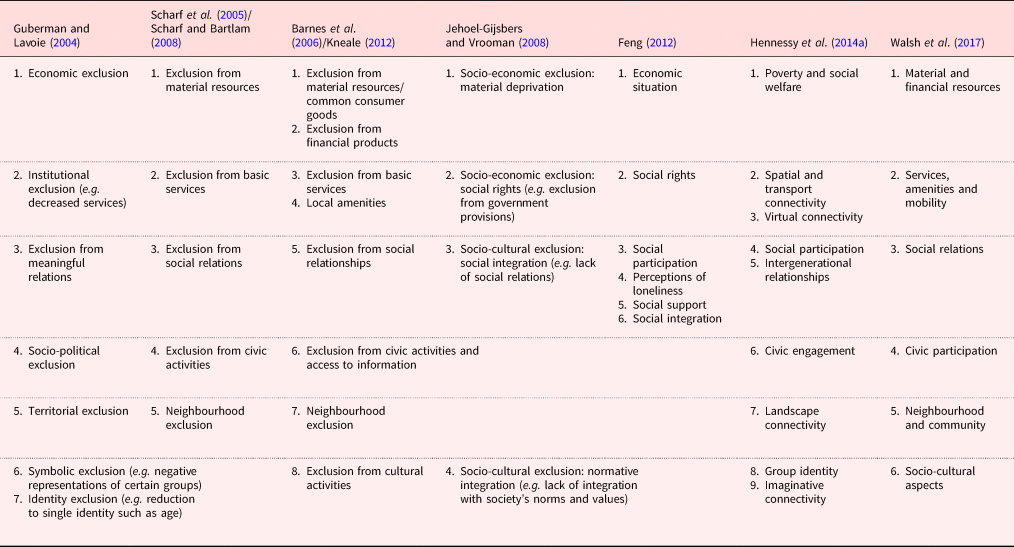

As represented here, and in long-held understandings of the construct (Room, Reference Room1999), social exclusion can be formed within and by place, linking disadvantage to both inequities in relation to neighbourhood and community, and the process of multi-dimensional exclusion itself (Walsh, Reference Walsh, Skinner, Andrews and Cutchin2018). In this respect, researchers have developed contrasting conceptual understandings of place in exclusionary processes. Existing conceptual frameworks map the interconnected domains of life where older people can experience disadvantage (e.g. social, economic, civic, etc.) (see Table 1, adapted from Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Scharf and Keating2017). Place, for the most part, is considered as one of these domains (e.g. Scharf et al., Reference Scharf, Phillipson and Smith2005; Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Blom, Cox and Lessof2006; Kneale, Reference Kneale2012), where its dimensions (e.g. geographic, infrastructural, socio-cultural) influence exclusionary experiences of local settings.

Table 1. Old-age exclusion conceptual frameworks

Source: Adapted from Walsh et al. (Reference Walsh, Scharf and Keating2017).

Two frameworks elaborate on how place can serve as a fundamental cross-cutting determinant of multi-dimensional exclusion. Jehoel-Gijsbers and Vrooman (Reference Jehoel-Gijsbers and Vrooman2008) acknowledge the agency of communities, amongst other actors, in creating and/or protecting against exclusion. Scharf and Bartlam (Reference Scharf, Bartlam and Keating2008) note how changes within rural settings can serve to exclude older residents in different domains, reflecting the dynamic elements of exclusion. Implicitly, place, through its practices and values, also shapes the meaning of exclusion, thus reinforcing its relative construction. Nevertheless, for the most part, the conceptualisation of place, and particularly rural places, is limited in these frameworks and often neglects the more complex mediating role. This is a reflection of how existing conceptualisations generally concentrate on domains of exclusion, rather than mediating factors impacting across domains.

Several frameworks acknowledge old-age exclusion's dynamic nature, and consider how the mechanisms/impact of disadvantage can change over the course of old age. However, consideration of the interrelationship between lifecourse experiences and place is largely absent, demonstrating a wider issue concerning an underdeveloped theoretical explanation of how exclusion and ageing processes intersect. Scharf et al. (Reference Scharf, Phillipson and Smith2005) and Scharf and Bartlam (Reference Scharf, Bartlam and Keating2008) offer the exception to this pattern, indicating that older adults’ past life experiences (e.g. longstanding difficult social relationships) can shape exclusion-in-place. Similarly, in the Grey and Pleasant Land project, Hennessy et al. (Reference Hennessy, Means, Burholt, Hennessy, Means and Burholt2014b) focused on different forms of connectivity for rural older people, and how life events and transitions can influence capacities for connectivity in place. There is now also an extensive body of work that highlights the influence of lifecourse experiences and critical life events in producing stratification and differential distribution of opportunities in later life (Dannefer, Reference Dannefer2003; Dewilde, Reference Dewilde2003; Elder et al., Reference Elder, Kirkpatrick Johnson, Crosnoe, Mortimer and Shanahan2003; Cavalli and Bickel, Reference Cavalli and Bickel2007). Particular risk associations described within the frameworks, such as living alone or being aged 80 or over, also highlight the role of social categorisations, including gender, socio-economic status and race/ethnicity, in the construction of old-age exclusion. However, inconsistencies in these associations have led to difficulties in explaining the nature of their relationship with exclusion (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Blom, Cox and Lessof2006).

The limited efforts to understand the role of mediating factors may, in part, be explained by the difficulty in identifying social exclusion in rural areas (Commins, Reference Commins2004; Connolly et al., Reference Connolly, Gavin, Maguire, McDonagh, Murray, O'Shea, Scharf and Walsh2010). Deprivation, poverty and marginalisation rarely occur within concentrated clusters of rural-dwelling people (Cloke and Davies, Reference Cloke and Davies1992). Consequently, pathways that lead to exclusion in rural communities and the factors that mediate these pathways become even harder to identify (Shucksmith and Chapman, Reference Shucksmith and Chapman1998; Shucksmith, Reference Shucksmith2004).

Approach and methods

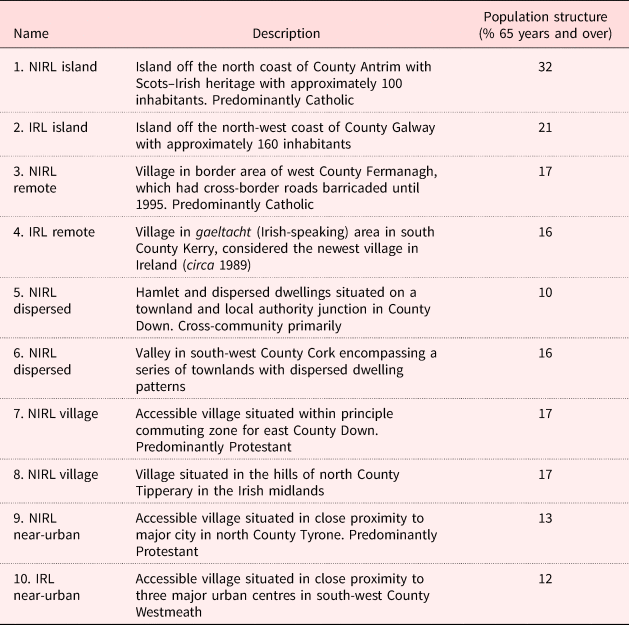

The research adopted a qualitative case-study design. This approach facilitated an in-depth exploration of a real-life whole object of study (i.e. older people's experiences of living in rural contexts) and the integration of a variety of evidence to represent this whole (Morgan, Reference Morgan, Cartwright and Montuschi2014; Bryman, Reference Bryman2016). While acknowledging that rural places can be fluid as well as bounded constructions, the case-study design focused on community sites as the central unit of analysis. Ten sites participated from across the island of Ireland. The research considered five different types of rural places in each jurisdiction: dispersed rural, remote rural, island rural, village rural and near-urban rural. These descriptive categorisations were derived from an Irish rural typology (Brady Shipman Martin, Reference Brady and Shipman Martin2000) and a UK rural classification (Bibby and Shepherd, Reference Bibby and Shepherd2005), and differ according to population density, settlement patterns and type of geographic location. Table 2 presents a brief description of each site. Site selection was based on community type, geographic spread and regional gatekeeper insights. The case-study analysis involved three major strands of data collection in 2011: stakeholder consultations, documentary analysis and site observation, and interviews with older people.

Table 2. Participating sites

Notes: IRL: Ireland. NIRL: Northern Ireland. Population age structure data for Northern Ireland is taken from the 2011 census (NISRA, 2011) and is reported at the ward level; population age structure data for Ireland is taken from the 2011 census (Central Statistics Office, 2011) and is reported at the district electoral division level.

Only data from older adult interviews are presented in this article. While stakeholder perspectives (collected from 62 stakeholders, in ten consultations across sites) help to contextualise this analysis, they are described in detail elsewhere (see O'Shea et al., Reference O'Shea, Walsh and Scharf2012; Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, O'Shea, Scharf and Shucksmith2014; Warburton et al., Reference Warburton, Scharf and Walsh2017).

To construct site profiles, the research team drew on supplementary material including local documentary and archive material. Data also included field-notes arising from site visits (typically two or three), photographs and charting of community space.

Older adult interviews

Interviews were conducted with 106 older residents to gather the lived realities of exclusion and participation in rural settings. The interviews took a lifecourse approach to capture the range of exclusionary mechanisms experienced over time (Bäckman and Nilsson, Reference Bäckman and Nilsson2011). Interviews were semi-structured to probe the relevance of key topics, but were sufficiently open to capture narratives on exclusion and place. Topics included daily routines, community change, accessing services, sense of home, community relationships and informal supports, and living standards. A short profiling questionnaire was used to collect demographic information. Participants were recruited with the assistance of stakeholder participants in each site. To ensure sample diversity and an adequate representation of at-risk groups, consideration in recruitment was given to: gender, people living alone, people aged 80 and over, people with chronic ill-health, religious/ethnic minorities and new-comer residents. Participants consisted of 49 men and 57 women aged 59–93 years (mean = 76; standard deviation = 7.6). Sixteen people were single, 44 married, 44 widowed and two separated/divorced. Forty-eight per cent of the sample lived alone, 33 per cent were aged 80 years and over and 35 per cent had moved into these communities. Ten per cent belonged to a religious minority in their communities. The sample also included three foreign nationals.

Data analysis and ethics

All interviews were conducted in English, recorded and transcribed. From an initial reading of transcripts, inductive codes were identified and used as a basis for developing a provisional coding framework for the interviews. The framework was further refined as a full thematic analysis was performed on the transcripts using NVivo analysis software. Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committees of the National University of Ireland Galway and Queen's University Belfast.

Findings: domains of rural old-age exclusion

Before focusing on mediators of social exclusion, we first present findings on five interconnected domains of social exclusion which emerged from participants’ accounts and encompassed different sub-dimensions. Participants could experience exclusion in one or multiple domains, while not experiencing it in others, with exclusion varying in degree and form across the lifecourse.

Social relations

Exclusion from social relations encompassed three dimensions: social opportunities, social resources, and loneliness and isolation.

In terms of social opportunities, while most participants considered themselves embedded in local relational communities, maintaining connections often proved challenging. Participants voiced disappointment at the absence of organised groups and formal activities. However, more emphasis was placed on reduced informal, spontaneous contact, and the ramifications of changing socialisation patterns:

You wouldn't walk up to a door now and shove in the door and, ya know, sit down. You'd have to have a kind of reason for going. (Male participant, near-urban, A04)

The closure of post offices, pubs and creameries contributed to the loss of meaningful social links, particularly for men. Decreased face-to-face contact, due to the need to commute and the perceived faster pace of life, also exacerbated susceptibility to this form of exclusion.

The quality of social resources was directly related to exclusion from social relations. Comprising family, friend and neighbour interpersonal relationships, such resources provided crucial support at critical times and represented symbolically significant reciprocity. Themes of interdependency, therefore, were prevalent within narratives. However, maintaining resources could be problematic. While some participants had no living relatives, others (e.g. islanders) lived a long distance away. Some participants had experienced relationship breakdown. A dwindling pool of friends and neighbours invariably diminished non-kin networks for many, with limited opportunities to cultivate new relationships.

Although most participants did not describe themselves as being socially isolated or lonely, isolation and loneliness emerged as outcomes of exclusion for some. The view that loneliness was a ‘part of life’ in rural communities was pervasive. Reduced social opportunities and networks – the fact that ‘there's not a lot of people to visit anymore’ (female participant, island, C02) – featured strongly in accounts of such feelings. Lacking someone to talk to could increase participants’ sense of being alone. As with the other sub-dimensions of exclusion from social relations, ill-health and disability could increase susceptibility to a sense of isolation.

Services infrastructure

Exclusion from services involved two dimensions: health and social care services, and general services.

Access to health and social care services was considered critical, and fundamentally linked to exclusion from services infrastructure. Participants described varying degrees of satisfaction with care services, reflecting different scales of infrastructure across sites, but also care needs. For village and near-urban dwellers in both jurisdictions, and dispersed Northern Ireland participants, health services were in close proximity. For others, accessing services required significant travel, which was particularly problematic for those requiring specialised treatment. Despite this, participants praised components of this infrastructure: community hospitals (where available), public/district health nurses and especially home-help services. However, participants were acutely aware that services were increasingly threatened by expenditure cuts and frequently described reduced provision. Local hospital closures in several sites reinforced feelings of vulnerability:\

…they isolated us completely! … the whole joke is if you have a heart attack, then don't worry you'll be dead before the ambulance comes! (Female participant, dispersed, S02)

For those who accessed home-based care, concerns centred on the dilution of public/district nurse services and the inability to access appropriate home-help allocations:

…I get 15 minutes. Now what under God can you do in 15 minutes?’ (Female participant, island, C05)

Access to general services (e.g. post offices, pubs, shops) followed similar patterns. Differences were again evident and reflected community type; given their more central locations, village and near-urban settings generally possessed more developed infrastructures. Yet, most participants referred to a longstanding depletion of local infrastructure, which was intensified during the prevailing economic recession. The closure of local service outlets could have a profound impact on essential provision and community sustainability. The loss of local police stations compounded these issues and introduced new feelings of insecurity. In terms of overall development trajectories, the islands were exceptions to these patterns, with vast improvements, including access to mains electricity and enhanced ferry services, having been implemented in participants’ lifetimes.

Transport and mobility

Transport and mobility exclusion was part of participants’ everyday lives and framed many of the other forms of exclusion they encountered.

Access to public bus networks was not available in several sites (remote/dispersed in Ireland; islands in Ireland and Northern Ireland). Where public transport was available, connections were often poor and intermittent, compounding geographic remoteness. Participants noted the limitations of using public transport to facilitate essential needs, particularly travelling to health appointments. The experiences of near-urban dwellers in Northern Ireland proved the exception; this particular community was located on a main transport corridor. Rural transport schemes, and a subsidised ‘social car’ programme in Northern Ireland, operated in most sites. Although these schemes were considered to provide an important resource, availability was again restricted, e.g. services in rural Ireland operated only once a week.

For these reasons, having access to a private car was considered a critical ‘life line’. Participants highlighted how the car was indispensable in maintaining independence and social connections. Associations with autonomy and self-sufficiency were prevalent in people's accounts, particularly for people experiencing physical mobility issues. However, private transport gave rise to other concerns, including the costs of running a car and questions about what would happen when car access was no longer an option. Some older women, who depended on their spouses to drive, experienced significant mobility challenges on bereavement. Similar difficulties were experienced by those who had ceased driving due to ill-health:

Jesus Christ it was [a big change], of course it was!’ (Male participant, remote, K07)

Safety, security and crime

Exclusion with respect to safety, security and crime impacted significantly on participants.

Feeling safe was highly valued and provided a social ‘freedom’. While many participants stipulated that safety was one of the reasons for remaining in place, some referred to a reduced sense of safety. Many individuals thought that crime had become more prevalent within their localities and were more cautious as a consequence:

Do [I] feel safe and secure living here? Yes, but not as much as I did. (Female participant, dispersed, K03)

Several participants reported direct experiences of crime which had undermined feelings of community trust. Although many of these instances involved the theft of farm machinery, robberies were sometimes more invasive, targeting participants’ houses while they were away or asleep. Home break-ins led some participants to question their commitment to living in the countryside.

For Northern Ireland participants, sectarianism was a theme within safety, security and crime descriptions. Significant challenges were typically set in the past. Participants were conscious of the Troubles and how they had left a mark on feelings of security within different communities, particularly where some sites were in close proximity to areas impacted by atrocities:

Well during the Troubles you know they [neighbours] were a wee bit standoffish, because some people were getting shot. They were in the [Ulster Defence Regiment], and then some of the Catholics were getting shot. And the Omagh bomb, there was people that lived in this area that was killed … And then gradually you heard how many they [killed] … Terrible, aye. It had an impact. It scared people. (Male participant, near-urban, S03)

Financial and material resources

Exclusion from financial and material resources involved the twin dimensions of income and material deprivation.

Income was directly linked to exclusion from financial and material resources, with most participants relying solely on state contributory and non-contributory pensions. With differences between absolute pension payments in the two jurisdictions, Northern Ireland participants reported that the basic state pension was just too low. While additional means-tested allowances, such as disability allowance or lone pensioner allowance, were acknowledged as contributing to living standards, those who fell outside thresholds expressed difficulty in surviving on the basic pension. Participants in both jurisdictions experienced difficulty paying household bills. People were concerned about rising energy costs, the financial burden of running a car and, in Northern Ireland, the payment of household rates. Covering such costs seemed to be particularly difficult when living alone.

Material deprivation contributed to exclusion from financial and material resources, albeit not always perceived experiences. Material disadvantage was generally underplayed or highlighted as having an impact on everyday life. However, it was clear from accounts of daily life, and from general observations, that a number of individuals, in objective terms, were materially deprived. Interviewers noted the poor quality of participants’ housing, worn-out clothes, bare concrete floors and worn-out furniture.

Nevertheless, interviewees for the most part did not describe a straightforward dichotomy between being excluded and not being excluded from financial and material resources. While most participants reported a reasonable or good standard of living, they articulated the need to budget and plan for expected and unexpected costs. Prioritising certain types of financial outgoings was viewed as a simple fact of life, the importance of which had been understood during harsher economic periods in the past.

Findings: mediators of old-age exclusion

A key feature of our analysis was the emergence from older adult narratives of four interconnected factors that acted as mediators of old-age exclusion across the five domains. Protecting against and/or intensifying experiences of exclusion, such factors were instrumental in shaping the potential for rural older people to be excluded.

Individual capacities

Findings highlighted how an individual's disposition and approach towards life determined how they perceived and dealt with various forms of exclusion.

Independence and personal agency

Many participants spoke about their sense of independence and their capacity to control their lives. Several did not want their family to feel obliged to support them, and referred to paying their own way and taking responsibility for their own wellbeing. Some participants wanted to avoid dependency itself, where requesting help was seen negatively. For others, independence encompassed the way they chose to live their lives, even if this sometimes meant living an isolated existence. In each of these examples, such approaches could affirm self-efficacy and identity. However, reflecting socially constructed values, these instances could also mask deeper exclusions.

For other interviewees the focus was on personal agency, representing an innate set of stoic traits that preserved continuity of self. Participants’ work roles and community involvement were sometimes a product of a recognised agency to effect change. Functional autonomy and health were not necessarily required in such situations, with agency instead emerging as a relative construct. This is illustrated by one older woman, with a chronic disability, who articulated her mastery over her surroundings:

Yerra, sure it is great to be able to get out of the bed. I come up to the kitchen. Go out the back kitchen and make [food]. I don't make that much … But still, yerra I'm as happy as Larry [happy as possible], thank God. As long as I'm not tied inside in the bed, that's all I need. (Female participant, dispersed, K05)

Coping and adaptive capacity

Many older participants developed a capacity to cope with and adapt to changing circumstances, helping them to be resilient in the face of exclusion. Sometimes this capacity was a by-product of individuals’ lifecourse and cohort experiences. In other instances, it took the form of conscious, protective strategies.

Most interviewees referred to the importance of remaining active. Routines, hobbies, volunteering and work provided a sense of purpose and helped to preserve continuity with respect to lifetime participation. A strong work ethic was dominant in how some people lived their lives:

I've a few cattle and I look after them and feed them … But it's not about money, do y'know. It's something to keep the mind occupied … Mentally, it's a big thing. People say ‘oh, I'll never work again, I'll retire’. But that's very easy said and not easy done. (Male participant, near-urban, E04)

Participants recognised how changes in their own abilities influenced their preferences, and acknowledged how continuous adjustment of expectations was an important part of adapting to life. Similarly, early life experiences of socio-economic hardship appeared to inform current assessments of need and satisfaction. Consequently, several participants spoke about how coping with material absences was generally anticipated:

Yes I am satisfied [even with no mains electricity and telephone] … but no-one didn't say to me, you could improve … So, therefore I took it for granted that I was happy enough … Life was never that bad. You see, some people say ‘oh God, aye it was’. Not really, ya know. (Female participant, remote, K05)

More purposeful strategies were also discernible. Religious faith provided a spiritual framework that allowed some participants to view losses differently, shielding against feelings of loneliness and despair. Some interviewees also recognised that social connections could be harnessed as a coping mechanism and a source of psychological strength. One older woman, who had suffered a number of bereavements, described her strategic and therapeutic visits to neighbours when feeling most upset:

So what can you do? Life is hard … I puts on my coat and I goes out. And I'd go to some house and we'd talk about something else. And they don't enquire there, but they always know (laughs) … Yes, find the one [neighbour] that's home. You'll always find the one with a couple of young children, she can't go anywhere like! So you go to that house … They'll say ‘Always call if you want to. Come anytime you want. The door's always open’. If it isn't they'd be gone somewhere. But [then] I'd go to the next one. (Female participant, dispersed, K02)

Several participants emphasised that above all there was a need to work at life. These individuals appeared to be more aware of their lifecourse and personal context, and as a consequence were accepting, but not in a fatalistic way, of their future life trajectories. Although these participants acknowledged that life was far from perfect, a palpable sense of contentment characterised their accounts:

You were better off to be struggling away with life … Well, ’tis my life. ’Tis, quite natural to me. So far, thank God, I've my own boss [wife] … Well now, I have ould angina and I don't know what road that's going to take. But yerrah, I have various old thing-a-majigs [health issues], but I takes no notice of them. I'm managing away … I know that we have problems and various things but, I don't live thinking like that, unless ’tis happening (laughs). (Male participant, dispersed, K10)

Lifecourse trajectories

Lifecourse trajectories served as a significant mediator of old-age exclusion. Some lives were more fragmented than others, incorporating more challenging transitions, which could act as tipping points into forms of social exclusion.

Bereavement

Bereavement was a major life event for many older participants, and could involve multiple deaths of family, friends and neighbours. Although it marked a period of significant transition, requiring adjustments in lifestyle and emotional consciousness, bereavement often represented a more catastrophic disruption of people's lives. Many participants talked about the death of their spouse as a major turning point, with social, financial and mobility implications. Mostly, however, participants described the impact of missing companionship, and emotional loneliness. The sense of loss was especially palpable within the accounts of participants who had experienced the death of a child. For those who had experienced the death of more than one child, narratives conveyed psychological longing and long-term impacts on wellbeing:

I do miss my daughter. I'll always miss my daughter. No matter what the world says, I'll always think of poor [daughter's name]. [Son's name] I don't think too much of, he was only 11 months. But I know his death when he died at 11 months was a big shock to me. And of course my first child was my very first, and you're so looking forward to your first baby. To find that it had died at birth, that's not a very pleasant thing to happen. So what can you do? Life is hard. (Female participant, dispersed, K02)

Health and functional independence

Life events surrounding health and functional independence dominated the biographies of many participants and emerged as significant influences in cross-domain experiences of exclusion. Several individuals spoke about physical and mental health conditions that had altered the direction of their lives and effectively removed some lifestages altogether:

And, I was there [England] about two years when I got [tuberculosis] … I thought I was going to die so I came back to Ireland. And eh, went to a sanatorium here in Ireland and eh, they told me I'd be three months in hospital, which I thought was endless. But it turned out that I was four years there … That's a big slice out of your life [at the age of 17]. (Female participant, dispersed, K03)

For others, health issues were a more recent age-related challenge accompanied by increasing debilitation. This was characterised by reduced physical function, increased need for pain management and recognition that life was changing. While some individuals drew solace from their relative state of wellbeing, others struggled and lamented the resulting loss of independence:

…since I retired a few years ago I took rheumatoid arthritis which is such a, (laughs) such a nuisance. Aw God it's awful … sometimes you go for months where you can't walk and you can't do things and you can't lift anything. Yeah, you can't comb your hair and, God almighty. So I feel that I'm growing old earlier than expected. (Female participant, island, C04)

Ageing

The most pronounced lifecourse transition for older participants in the research was old age itself. Bound within old age are significant life changes, including those around age-related health, retirement, family and community roles, and symbolic changes in status. A number of individuals had difficulty in accepting such changes. These participants appeared more comfortable speaking about what life was like in the past and portrayed a set of structures and values that were more in line with what they considered appropriate. Other accounts went further and conveyed a longing for a life lost, describing past patterns of participation in communities as being full, active and satisfying:

When I was em, say in my twenties, you know, it was very alive, full of vibrancy, full of community. And nobody need be without anything that anybody else had … But I was so much a part of that. That was my life. Because I was never anywhere else. I never went away to college or to school or to anything. And that was me. That was my life. And it was marvellous like d'ya know … There's a lot of individualism now. (Female participant, near-urban, E12)

Place

Place was pervasive in participants’ narratives. Through an intermeshing of objective and subjective elements, place could function as an actor in the exclusion process, shaping domain-specific disadvantage and wellbeing.

Geographic and natural elements

Participants referred to the geographic and natural components of place, highlighting such characteristics as distance and accessibility. For some, particularly those in centrally located sites (near-urban, village), these were positive features emphasising relational and infrastructural connectedness within and beyond areas. In more remote locations, they could underlie a sense of disconnection. Interviewees suggested that harsh winter weather could intensify feelings of isolation and create hazardous conditions. In contrast, the aesthetic landscape, fresh air and quietness appeared to offset the challenges of accessibility for some. But even here several informants acknowledged that preferences for such characteristics could change over time:

Quietness I suppose [is the best thing]. If you look for quietness. Well now you asked me there a while ago did I ever get restless when I was young: I thought it was horrible in my teen days here, but now I wouldn't go out of it in a thousand years. Yerrah I couldn't, and I wouldn't. (Male participant, remote, K06)

Change and community cohesion

The demographic and social structure of these sites was shifting. As participants inextricably linked place and community, interviewees were particularly conscious of local change processes and socio-cultural factors that impacted on the cohesive culture and social fragmentation of their communities. Participants highlighted that, due to the death of peers and the outward migration of younger populations, vacant homesteads had become more prominent in their locality. This could disrupt generational and familial continuity, and diminish local connectivity for individuals:

My old neighbours are all gone … on this side of the main road, there's no old neighbour left now that we lived with. Houses, their houses are closed … They passed away boy. Age got them. Oh age got them … There was a lot of [our relatives] there. There isn't a one there now. I'm the last of the little heroes. (Female participant, dispersed, K05)

Most sites had also experienced inward migration. Participants referred to new commuting populations (especially in near-urban and village sites), seasonal residents (foreign national, national), and retirement (primarily in Northern sites) and return migration. Such processes meant connectedness was no longer resolute. For some, this reflected a contemporary affluent rural life, where interdependency between neighbours was no longer necessary. For others, it was a function of no longer knowing all neighbours. While new residents were considered to invigorate a locality, there was a sense that they often remained outside community structures. New populations were seen by some to present a more significant challenge where tensions between new and long-term residents placed considerable strain on interpersonal relationships. This led a number of new residents to question whether they would ever be included:

They still have this thing about, they call them ‘blow-ins’ here … If you wanted to come and feel at home, and be included you would have to wait a while. And you could be very disappointed. (Female participant, dispersed, S02)

Tensions in Northern Ireland communities were sometimes long-standing, reflecting traditional jurisdictional religious differences. While relations between Protestant and Catholic populations were described as having generally improved, several participants from both communities described how caution was still required. Although the communities were not extensively affected by the Troubles, people had been killed within some localities, illustrating that even these areas had experienced violent trauma. However, while many participants acknowledged the remnants of sectarian tensions, it was felt that persisting issues stemmed from a minority on both sides, but were largely superseded by a cross-community rural bond:

I always thought it was there in the background. But in a rural community you depend a lot on your neighbour. Neighbours help one another out. And there was always that respect. (Female participant, near-urban, K3)

Attachment and belonging

Attachment to place and a sense of belonging not only protected against feelings of dislocation, but appeared to be integral to coping with and re-prioritising more objective forms of disadvantage.

Interviewees talked about the landscape and the quality of their countryside. Older farmers and fishermen, in particular, spoke in depth about the land and sea. Providing a livelihood and a food source, these resources were an inherent part of this group's lifecourse narratives. For many participants, self-identity, wellbeing and a sense of continuity were bolstered by their continued embeddedness in these environments:

If I was there now of a Sunday, I'd go home from mass and I'd have things done and … I'd go off through the fields. I could travel, God I could walk miles down through everyone's nice fields you know and places that you were when you were a gossan [boy] … If you just go out on the field and a cow is after having a calf and you see him racing around the field and everything good. It's, it's a great lift to anyone. (Male participant, near-urban, A04)

A sense of home was integral to notions of belonging for participants. Encompassing both a dwelling and the wider community, interviewees talked about the relationships and memories that they had accumulated, their feelings of security and familiarity, and how these places were central to their life story. For those who were native to these sites, the focus was often on being born and reared in their community, and the local cultural values that were inherited through this connection:

This is my roots. And they're here, firmly established like the oak tree in the soil. (Female participant, village, E12)

Other participants placed greater emphasis on relational aspects of home. This was linked to the proximity of family and, particularly for older women, to home as a fulcrum of child rearing. Participants also described how home was reinforced by the considerable work invested in making place. This encompassed an emotional and symbolic investment in nurturing a sense of home and more practical efforts to buy a dwelling or create a viable farm homestead.

A small number of interviewees felt that they were not at home in their rural community. Typically, these participants were non-native residents who described home as being elsewhere. While some had relocated in later life, in many cases these individuals were older women who, reflecting socio-cultural traditions, married into farm homesteads but had not forgotten their original home. Sometimes, feelings of lack of acceptance were a key detractor of a sense of home. But in other instances, participants perceived a distinction between themselves, as non-natives, and natives. This was often independent of their length of residence:

I've been here 66 years now. I tend to say that I'm a long-term resident. My definition of an islander is somebody who is born and reared on an island … It's an inheritance, let's put it that way. (Female participant, island, K04)

Macro-economic forces

Older people's accounts suggested that macro-economic forces influenced the potential for old-age exclusion in rural communities. These factors, which in most cases reflect broader global patterns, shaped many of the local changes occurring within sites at the meso-level, and impacted on older people's lives at the micro-level. Findings presented across this paper (change and community cohesion, social relations, service infrastructure) demonstrate this interlinkage.

The most influential macro-level factors concerned changes in the economic structure of rural areas, most notably the decline and reform of agriculture, mediated by national and European agricultural policy and increasing urbanisation. Participants noted the demise of traditional resource industries, such as farming and fishing, and the subsequent reduction in economic opportunities. Leading to outward migration to urban centres, interviewees in several sites described how there just was not the same number of people in these communities anymore:

See farming changed completely. Is one of the things, that there's very, very few full-time farmers so, as a result, the place is nearly empty by day d'ya know. There's very few except the slow fellas like myself knocking around. (Male participant, village, E07)

Linked to these socio-economic transformations, and arguments of economies of scale, most communities showed evidence of cycles of rural decline: depopulation leading to a reduction of public services, leading to further outward migration, which in turn resulted in additional service reduction. As outlined in findings on exclusion from social relations and service infrastructure, in some sites the depletion of local infrastructure reduced older people's access to services and reduced the number of places where people could gather.

Given the period of data collection, the economic recession was the most immediate concern for many participants. The economic downturn and significant reduction in public spending in both Ireland and Northern Ireland was described as affecting life on several levels. As previously noted, participants were concerned with closures of community-based health and social care services, and reduced budgets for community-based services. Interviewees from several sites highlighted rising unemployment rates in their communities, noting how job losses were damaging the fabric of rural communities. Interviewees stated that, as a consequence, emigration to other countries was a growing problem. While none of the participants spoke directly about the implications for their own support networks, there were concerns that emigration would impact on informal support structures, including care-giving potential within families. Participants also noted that emigration was impacting on the sustainability of community groups essential to local vibrancy:

Oh God. One thing was if we could see this recession lift a bit is one of the things … It's impacting on the [GAA] club, it's impacting on the population because people now with the qualifications are having to leave. (Male participant, near-urban, E02)

Rurality and mediated exclusionary processes

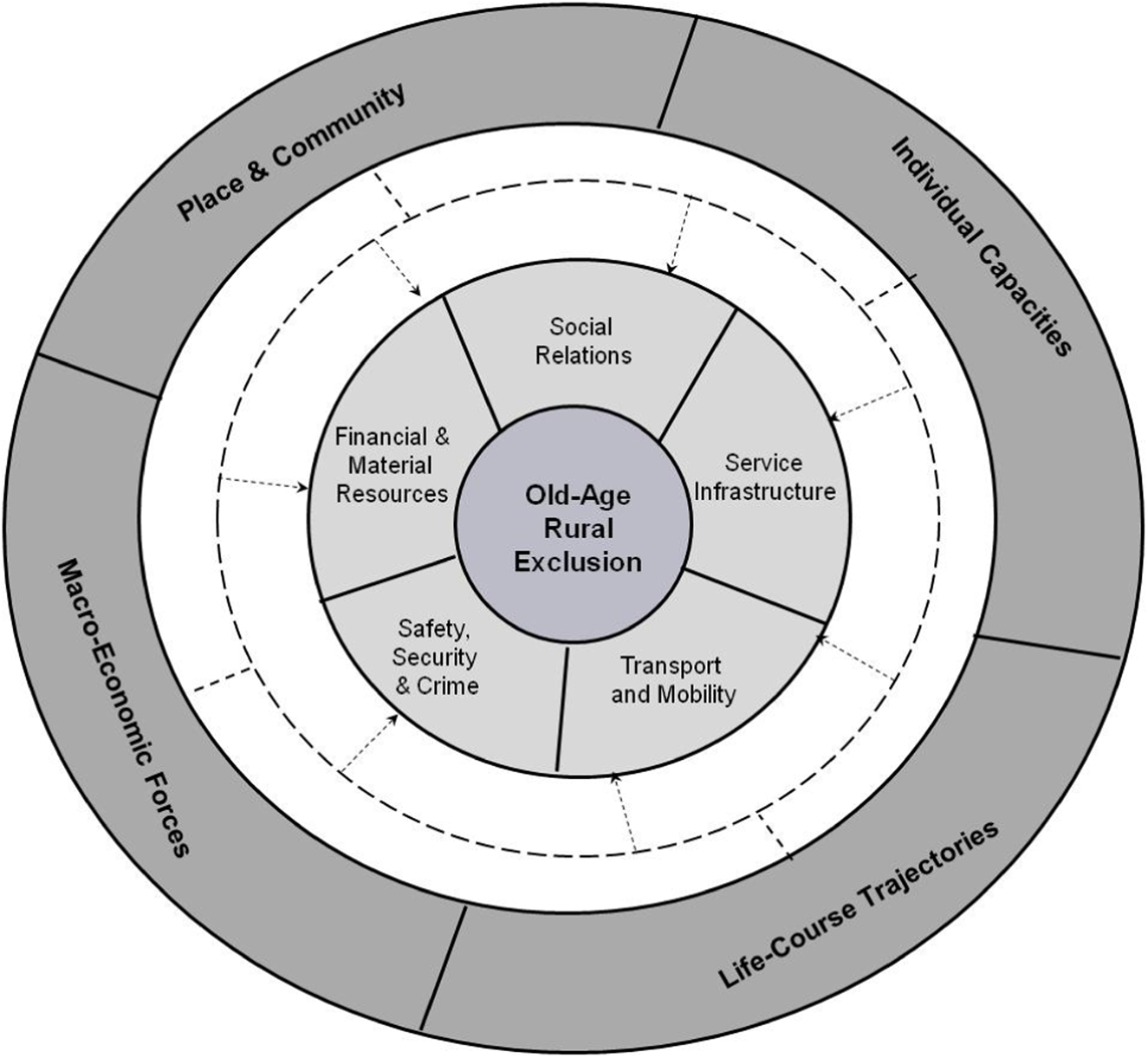

This article has aimed to increase understanding of rural old-age social exclusion, with a particular focus on unpacking the role of mediating factors in the lifecourse experiences of older people living in diverse rural places. The task of disentangling the complex causalities of old-age exclusion was outside the scope of this analysis. Yet, our research findings provide valuable insight into the interrelationship between ageing, rurality and exclusion from participants’ lived experiences. Figure 1 presents a conceptual framework on rural old-age social exclusion that advances the role of mediating factors as a conceptual priority in understanding the construction of disadvantage for rural-dwelling older adults.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework on old-age rural social exclusion.

Representing a key contribution of this article, the framework goes beyond the more orthodox domain multi-dimensionality of other conceptualisations to identify a multi-layered construction. Mediating factors operate singularly or in combination to intensify or protect against domain-specific experiences of disadvantage. Associations between these factors and later-life outcomes (exclusionary or otherwise) have been documented, including within broader models of age-related disadvantage (Cavalli and Bickel, Reference Cavalli and Bickel2007). For example, research has demonstrated the importance of agency and adaptive capacity for resilience reservoirs and later-life wellbeing outcomes (Wiles et al., Reference Wiles, Leibing, Guberman, Reeve and Allen2012). Likewise, the significance of critical life transitions in determining disadvantage trajectories has been well documented (Scharf et al., Reference Scharf, Phillipson and Smith2005; Elder and Shanahan, Reference Elder, Shanahan, Damon and Lerner2006). Place, its socio-cultural context and its relationship to a sense of belonging, has been noted to have multifaceted impacts on older adults’ experiences (Burholt et al., Reference Burholt, Curry, Keating, Eales, Hennessy, Means and Burholt2014; Walsh, Reference Walsh, Walsh, Carney and Ní Léime2015). There is also substantial research on the influence of macro forces on rural environments and social and economic outcomes for older residents (Giarchi, Reference Giarchi2006; Phillipson, Reference Phillipson2007).

These linkages have received little attention in previous frameworks of old-age social exclusion (with the possible exception of Jehoel-Gijsbers and Vrooman, Reference Jehoel-Gijsbers and Vrooman2008; Hennessy et al., Reference Hennessy, Means and Burholt2014a), contributing to stagnation in conceptual innovation. The identification of mediating factors allows for a more complete picture of exclusion for rural older people, demonstrating both its dynamic and sometimes ambiguous nature. While domains of exclusion are easier to measure, it is the mediating influences that can be considered to shape: (a) the extent to which domain-specific exclusion is experienced; (b) an individual's ability to cope with/be resilient towards that exclusion; (c) the internal choices of an individual, based on their life history and place links, to focus on and prioritise other areas of life; or (d) all three. In essence, the framework points to the fine margins between those who experience exclusion and those who feel they do not. In this research, it was the experiential aspects of place, reflecting an older person's relationship with their community, that emerged as being particularly significant as a mediator. However, it is acknowledged that this representation is likely to be a simplification, where exclusion domains themselves can be framed as different dimensions of rural places. Thus, aspects of place may in effect serve as a domain and a mediator of exclusionary experiences.

In terms of exclusion domains, the framework confirms similar forms of exclusion to those in previous non-rural models (e.g. Kneale, Reference Kneale2012).

While both exclusion from transport and mobility, and safety, security and crime, have been incorporated in other frameworks under broader categorisations of services and community, respectively, it is the way in which they emerged in participants’ accounts that warranted their separation into distinct domains. This is supported by previous research that testifies to their importance in later life (De Donder et al., Reference De Donder, Verté and Messelis2005; Shergold and Parkhurst, Reference Shergold and Parkhurst2012; Ward et al., Reference Ward, Somerville and Bosworth2013). Transport and mobility encompassed more than just service provision, implicating the importance of the private car, transport (e.g. driving cessation) and lifecourse (bereavement) transition points, and even individual mobility strategies. Safety, security and crime, while representing some dimensions of neighbourhood at the domain level, also derived from instances, agents and discourses that sat outside place boundaries and meso levels – particularly in relation to sectarianism in Northern Ireland.

It may also be argued that civic participation should be included within the framework as another domain of exclusion, given findings related to community involvement in our analysis. However, in this research, exclusion from civic participation was not described. Instead, such forms of engagement were primarily discussed positively in terms of realising personal agency and efficacy. Nevertheless, the absence of this theme from participants’ narratives does not necessarily reflect an absence in reality.

While we acknowledge that the framing of civic, transport and safety elements is open to other interpretations, conceptualising such processes in other ways would not accurately reflect how older people encountered these forms of exclusion in this study. The findings on domains also illustrated that there are complex interactions between areas, which in part determine the construction of disadvantage. As with other frameworks, domains thus represent a set of outcomes, and a set of process components that produce outcomes in other domains.

There are at least three layers to the relationship between rurality and old-age social exclusion. First, rural-dwelling older people can be particularly impacted by changes in population structure, fragile social connections and weak services, resulting in a dual marginalisation arising from age and place (Hedberg and Haandrikman, Reference Hedberg and Haandrikman2014; Warburton et al., Reference Warburton, Cowan, Winterton and Hodgkin2014; Skinner and Winterton, Reference Skinner, Winterton, Skinner, Andrews and Cutchin2018). The dynamics of public provision, and the economic efficiency criteria of resource allocation, underlie some of these vulnerabilities. Structural change processes, including increased urbanisation and shifts from primary production, underlie others (Skinner and Hanlon, Reference Skinner, Hanlon, Skinner and Hanlon2016). While such processes have been noted for rural (Keating, Reference Keating2008; Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Joseph and Herron2013) and urban dwellers (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Lavoie and Rose2012), it is the rate at which these changes have occurred for this sample, and the way they intertwine with cycles of decline, that is particularly significant – the proportion of national employment accounted for by Irish agriculture, for example, shrank from 54 per cent in 1926 to just 5 per cent in 2009 (Kearney, Reference Kearney2010).

Second, the strength of the link between place and identity was also apparent, especially for long-term and native residents. An intense attachment to place, manifest as a physical, social and autobiographical ‘insideness’, has been suggested to help rural older adults maintain identity and self within changing environments (Rowles, Reference Rowles1978, Reference Rowles1983). Place is synonymous with cultural narratives of attachment and identity in Ireland (Duffy, Reference Duffy2007; Inglis, Reference Inglis2009). Land also holds rich symbolic and cultural meaning. As land rights were a key impetus in the mobilisation of the Irish nationalist movement during British rule, land was in effect a component of national Irish Identity (Kane, Reference Kane2000). Such factors underlie the cultural significance of place as an inherited set of values for some rural older adults on the island of Ireland (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, O'Shea, Scharf, Skinner and Hanlon2016). This may partially indicate why some individuals also struggled to create a sense of home after relocating.

Third, rural old-age exclusion possesses a particular hidden nature with the tendency for older people to have low expectations for participation (O'Shea et al., Reference O'Shea, Walsh and Scharf2012). The social construction of norms and even stoic ideals are, of course, powerful in shaping expectations (Eales et al., Reference Eales, Keefe, Keating and Keating2008; Wiles et al., Reference Wiles, Leibing, Guberman, Reeve and Allen2012). Particular cohort experiences, recognising the distinctiveness of those experiences for participants born between 1918 and 1952, with respect to social and economic hardship, were evident as were gender roles. Such conditions constrained the choices and opportunities available to this group. With substantial emigration in the 1930s, 1950s and 1960s, these participants could be viewed as those left behind with limited life chances or, perhaps more so, as a survivor population who inherited land and/or successfully negotiated social conditions to remain at home. Values, such as a strong work ethic, and local attachments could also be considered to reflect an agrarian post-colonial society, where older adults in both jurisdictions grew up with limited state intervention. All of these circumstances can inform the application of mediating factors, and in some cases mask the individual deeper forms of structural disadvantage. Nevertheless, some participants were aware of the conditions of their earlier lives, actively reflected on how they influenced their experiences and still appeared to be resolute in their priorities. It would be inaccurate to say that rural older people are uniquely resilient. This research, however, suggests that there is a particular form of place-based and cultural resilience which stems from the traditions of communal activity, a strong work ethic and an inherent attachment to rural living (Wiles et al., Reference Wiles, Leibing, Guberman, Reeve and Allen2012; Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Evans and Wiles2013).

With respect to community types, there were clear impacts as a result of differences in infrastructure, location and settlement structure. These differences were most apparent for exclusion domains, e.g. individuals in remote and island communities inevitably received fewer services than those in near-urban settings. It becomes more complicated, however, when accounting for the relative impact of these experiences. It would be wrong to assume that the potential for exclusion is uni-directional across such geophysical and infrastructural dimensions: aesthetic elements intertwined with these characteristics can provide compensating factors for older people. Aside from differences in typology, each community possessed its own particular cultural and historical milieu, contributing to unique social diversity within each site. A part of that diversity was that some communities, such as remote settings, had to fight for what they had, and consequently possessed a stronger capacity to adapt to socio-economic shocks in their localities.

Differences between communities in Ireland and Northern Ireland were also apparent. Given higher rates of urbanisation in Northern Ireland, community sites were more accessible with a better-developed infrastructure. In general, the older populations in Northern Ireland sites seemed to be more diverse, with a greater mix of retirees, non-farming residents and religions. While this had an impact on cohesion in some communities, in others it did not. Distinctions in the jurisdictions’ welfare systems meant that public service provision was less developed in Irish sites and pension payments were lower for residents of Northern Ireland settings. The history of the Troubles in Northern Ireland added another specific dimension to issues of integration and security. The findings, however, showed that exclusion across the domains did not differ according to religious tradition. Even where issues of sectarianism and religious integration did exist, the impact of participants’ experiences was similar.

While difficult to disentangle over the course of a single interview, wealth, land ownership, educational attainment and socio-economic status could combine to influence individuals’ potential for exclusion in later life. However, robust associations with exclusion outcomes were difficult to discern. This supports patterns evident in analysis of survey data where correlations with other risk factors mean assessing these relationships is problematic (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Blom, Cox and Lessof2006). Nevertheless, and as with lifecourse theoretical models of inequalities (Dannefer, Reference Dannefer2003; Ferraro and Shippee, Reference Ferraro and Shippee2009), there was a sense that some participants accumulated risk more than others. But in many cases such risk appeared to be linked to particular critical life transitions, such as bereavement or the onset of ill-health, and residential tenure, as much as particular social categories.

Finally, the capacity of some participants to respond to adverse circumstances, and shifts in their personal and environmental context, were especially evident. This is reflective of processes of adaption described in ageing-in-place and environmental gerontology literature. For example, in a theory of ‘place integration’, Cutchin (Reference Cutchin2003, Reference Cutchin, Skinner, Andrews and Cutchin2018) details how older people assess their level of disintegration with place, as a result of personal/place change, and make decisions and implement actions to achieve reintegration – ultimately remaking meaning and identity in place. Likewise, Golant (Reference Golant2011, Reference Golant, Skinner, Andrews and Cutchin2018) notes how older people can use accommodative strategies, such as reformulating goals, to achieve a sense of comfort and control in their environment so as to maintain a ‘residential normalcy’. Older people in this study, and as documented elsewhere, were however not just adapting to circumstances outside their control but were very much active agents in place (Golant, Reference Golant2003; Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, Phillipson and Scharf2013b). While local contributions testified to this, so too did older people's roles as cultural informants and performers of routines and social practices of place. This was largely independent of functional health.

Conclusion

Our understanding of rural ageing, particularly from a critical perspective, requires substantial development. The conceptual framework presented in this article suggests that the role of mediating factors is central in the construction of rural old-age social exclusion. Individual capacities, lifecourse trajectories, place and macro-economic forces singularly and in combination determine experiences of exclusion for rural-dwelling older people across a range of domains of exclusion. This framework may contribute to the development of more global explanations of rural and place-based old-age exclusion. However, further work is required to refine these understandings and explore their relevance for other jurisdictions. A longitudinal qualitative design, incorporating more traditional ethnographic methods, would allow for more in-depth analyses of exclusion and participation, as would more refined quantitative exclusion indicators. The complexity of the interdependencies between rurality, ageing and exclusion also give rise to a multitude of relationships that require more detailed study. Future research could, therefore, usefully unpack the links between exclusion domains, and, perhaps more critically, the interrelationship between different mediating factors and their intertwined impact on exclusion in later life.

Financial support

The original research, on which this article is based, was funded by the Centre for Ageing Research and Development in Ireland (CARDI). In September 2015 CARDI became the Ageing Research and Development Division within the Institute of Public Health in Ireland (IPH). This article is a product of a writing collaboration arising from the COST Action CA15122 Reducing Old-age Social Exclusion – ROSEnet (www.rosenetcost.com), supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology). COST is a funding agency for research and innovation networks (www.cost.eu).

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committees of the National University of Ireland Galway and Queen's University Belfast.