Introduction

Ageing in India has become a critical demographic change and concerns regarding elder care and support are gaining more attention (Bloom, Reference Bloom2011; James, Reference James2011). The population of India stood at 1,210 million with older adults (ages above 60 years) accounting for 8.6 per cent of the total population (Chandramouli, Reference Chandramouli and General2011). The demographic transition in India is, however, not uniform with a few states ageing at a faster pace than the rest (James, Reference James2011). The proportion of older adults aged above 60 years varies from as high as 12.4 per cent in the state of Kerala to as low as 6.5 per cent in the populous Indian state of Uttar Pradesh (Chandramouli, Reference Chandramouli and General2011). The southern Indian state of Kerala has not only some of the most advanced development indicators among Indian states (Susuman et al., Reference Susuman, Lougue and Battala2014) but also boasts of the largest number of emigrants working abroad (Varghese, 2011; Zachariah and Rajan, Reference Zachariah and Rajan2016). A typical emigrant from Kerala is from the young working-age range of 20–39 years and nearly 30 per cent of the primary emigrants were men who had left behind their wives and children, along with their parents (Rajan, Reference Rajan2014). Although Kerala ranks high with regard to socio-economic indicators among Indian states, socio-economic circumstances and lack of employment opportunities often lead young adults to migrate in an attempt to establish their life abroad, leaving behind older parents (Chua, Reference Chua, Broz and Münster2016). Through analysing interviews conducted among left-behind older adults and their primary care-givers from emigrant households in the Indian state of Kerala, this paper discusses how reciprocal motives underlie acts and obligations to care-giving between older adults and their family care-givers.

Strong reciprocal filial obligations exist in India, as in many Asian societies, and are culturally effectuated through intergenerational co-residence (Croll, Reference Croll2006; Vera-Sanso, Reference Vera-Sanso2006; Gupta, Reference Gupta2009; Lamb, Reference Lamb2013; Ugargol et al., Reference Ugargol, Hutter, James and Bailey2016). The notion of family is extended to include non-coresident children, their spouses and their children too (Verbrugge and Chan, Reference Verbrugge and Chan2008). Cultural models or schemas are known to influence the provision of filial support and care for older adults in India (Dandekar, Reference Dandekar1996; Rajan et al., Reference Rajan, Sarma and Mishra2003; Hanspal and Chadha, Reference Hanspal and Chadha2006). The Indian state exhorts the family to care for its older adults by invoking Indian tradition, culture and filial piety, while limiting its role in providing a safety net for older adults either through economic support or aiding care-givers (Rajan and Balagopal, Reference Rajan and Balagopal2017; Ugargol and Bailey, Reference Ugargol and Bailey2018). Traditionally, older parents live with a married son and are most likely to receive care, when needed, from the daughter-in-law (Bongaarts and Zimmer, Reference Bongaarts and Zimmer2002). As demographic shifts become apparent with decreasing multigenerational co-residence and increasing nuclearisation of families, concerns arise about care availability to older adults (Rajan, Reference Rajan and Balagopal2007; Bloom et al., Reference Bloom, Mahal, Rosenberg and Sevilla2010; James, Reference James2011). In addition, emigration of adult sons is bringing left-behind family members, especially older spouses, daughters-in-law and female siblings, into care-giving roles. Care-giving is commonly a gendered role with women taking on the responsibility, usually the spouse of the older adult or the daughter-in-law with support from other family members (Bongaarts and Zimmer, Reference Bongaarts and Zimmer2002; Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Rowe and Pillai2009).

Spousal motivation to providing care to partners has been considered normative and most studies have largely ignored the inherent reciprocity, except for a few (Lewis, Reference Lewis1998; Quinn et al., Reference Quinn, Murray and Malone2014). More emphasis has been laid on filial exchanges and how older parents received reciprocal support from their adult children (Neufeld and Harrison, Reference Neufeld and Harrison1995; Hsu and Shyu, Reference Hsu and Shyu2003; Funk, Reference Funk2012, Reference Funk2015), while only a few studies have looked at dynamic bi-directional reciprocal exchanges between older adults and other family members (Dwyer et al., Reference Dwyer, Lee and Jankowski1994; Raschick and Ingersoll-Dayton, Reference Raschick and Ingersoll-Dayton2004; Breheny and Stephens, Reference Breheny and Stephens2009; Verbrugge and Ang, Reference Verbrugge and Ang2017; Ugargol and Bailey, Reference Ugargol and Bailey2018).

In the Indian context, adult child migration can significantly disrupt a complex family system based on cultural values and expected roles (Miltiades, Reference Miltiades2002). When adult children emigrate, the cultural norms that govern care exchange between older adults and children-in-law (in lieu of children) and the experience of older parents left behind are being increasingly explored across countries where migration of working-age adult children continues, leaving children and often older parents behind (Antonucci et al., Reference Antonucci, Fuhrer and Jackson1990; Connelly and Maurer-Fazio, Reference Connelly and Maurer-Fazio2016). The migration of young adult children is leading to negative consequences for left-behind ageing parents who have reported loneliness, isolation and loss of basic support. In Mexico, Antman (Reference Antman2010) has reported that the migration of adult children has been associated with poorer physical and mental health outcomes for left-behind older parents. Dykstra and de Jong Gierveld (Reference Dykstra and de Jong Gierveld2004) found that social and emotional loneliness among older Dutch women was negatively associated with weekly contact with their adult children. Even among older European parents, those who saw or talked to their children more often than once a week had significantly lower levels of depression (Buber and Engelhardt, Reference Buber and Engelhardt2008). From instances in Asia, among the Chinese elderly, living alone was associated with low subjective wellbeing and those living with immediate family members reported improved general wellbeing (Chen and Short, Reference Chen and Short2008). Böhme et al. (Reference Böhme, Persian and Stöhr2015) have reported that in Moldova, which has one of the highest emigration rates in the world, there are positive effects of income on left-behind older adults including improvement in Body Mass Index, mobility and self-reported health, however, older adults reported decreasing social contact and loneliness. In India, out-migration by an adult son has been negatively associated with the health of parents ‘left behind’ (Falkingham et al., Reference Falkingham, Qin, Vlachantoni and Evandrou2017).

Given this global empirical range within a resilient but tested cultural context of multigenerational living and family-based support for older adults in India (Lamb, Reference Lamb2013; Ugargol and Bailey, Reference Ugargol and Bailey2018), we explore reciprocity in care-giving across possible relationship types: spouses, children and children-in-law. The aim of this paper is to examine how older adults and their care-givers perceive reciprocity, interpret reciprocal support exchanges and find meaning in their care exchange relationship. We undertake this exploration of reciprocity and aim to answer the research questions on whether reciprocity influences care-giving expectations, care-giving responsibilities, and implicit and explicit care exchanges between older adults and their family care-givers through face-to-face in-depth interviews of 24 pairs of older adults and their primary care-givers from emigrant households of Kerala, India.

Theoretical framework

The norm of reciprocity was classically defined as ‘certain actions and obligations which work as repayments for the benefits received’ (Gouldner, Reference Gouldner1960: 170). Within this norm, recipients of support remain indebted to the giver until balance is restored by an equivalent repayment. Academic interest in reciprocity continues as the norm is found to be universal, stable and reliable to account for human behaviour. If it is true that reciprocity directs care provision between generations, then the support provided by adult children to older parents will not erode even in the midst of modernisation and ageing societies (Leopold et al., Reference Leopold, Raab and Engelhardt2014). While Dowd (Reference Dowd1975, Reference Dowd1980) argued that ageing itself can be viewed as a process of exchange, others emphasised the interdependence in dyadic relationships and mutual exchanges (Molm and Cook, Reference Molm and Cook1995; Silverstein et al., Reference Silverstein, Conroy, Wang, Giarrusso and Bengtson2002; Molm et al., Reference Molm, Collett and Schaefer2007).

Intergenerational reciprocity is thought to be based on earlier parental support given to children that acts as an investment strategy (Silverstein et al., Reference Silverstein, Conroy, Wang, Giarrusso and Bengtson2002, Reference Silverstein, Conroy and Gans2012); however, reciprocal support exchanges are not time-limited but extend through the lifecourse with changing motives and incentives (Call et al., Reference Call, Finch, Huck and Kane1999; Leopold et al., Reference Leopold, Raab and Engelhardt2014; Stöhr, Reference Stöhr2015). Though support provided by younger family members can be in exchange for the support received from parents earlier, family relationships consist of dynamic bi-directional ongoing exchanges where even present provision of support can motivate future intergenerational transfers (Raschick and Ingersoll-Dayton, Reference Raschick and Ingersoll-Dayton2004; Schwarz and Trommsdorff, Reference Schwarz and Trommsdorff2005; Silverstein et al., Reference Silverstein, Conroy and Gans2012) and the balance of power and resources shift over time (Call et al., Reference Call, Finch, Huck and Kane1999; Molm et al., Reference Molm, Collett and Schaefer2007). Care-giving as a process of mutual exchange can result in both costs and rewards to those who provide care and all participants look to maximise rewards and minimise costs in the relationship (Silverstein et al., Reference Silverstein, Conroy, Wang, Giarrusso and Bengtson2002; Lowenstein et al., Reference Lowenstein, Katz and Gur-Yaish2007; Ugargol and Bailey, Reference Ugargol and Bailey2018). Though older adults might face difficulty in directly reciprocating support received (Akiyama et al., Reference Akiyama, Antonucci, Campbell and Sokolovsky1997), past provision of care usually raises the benevolence for older adults (Hsu and Shyu, Reference Hsu and Shyu2003; Verbrugge and Chan, Reference Verbrugge and Chan2008; Verbrugge and Ang, Reference Verbrugge and Ang2017).

Many types of reciprocity have been recognised by researchers. Generalised reciprocity has been discussed as a motivation to return care where exact, specific or in-kind repayment is not expected (Molm et al., Reference Molm, Collett and Schaefer2007; Komter and Schans, Reference Komter and Schans2008) and which may be a true representation of how family relationships actually operate (Dwyer et al., Reference Dwyer, Lee and Jankowski1994; Call et al., Reference Call, Finch, Huck and Kane1999; Funk, Reference Funk2012). The repayment of the debt also need not be immediate but can be delayed and is termed delayed reciprocity (Neufield and Harrison, Reference Neufeld and Harrison1995; Funk, Reference Funk2012, Reference Funk2015). Reciprocity arising in response to parental care and support where the repayment need not be of the same kind and could be established through a series of intergenerational exchanges over the lifecourse (Antonucci, Reference Antonucci, Binstock and George1990; Silverstein et al., Reference Silverstein, Conroy, Wang, Giarrusso and Bengtson2002; Stöhr, Reference Stöhr2015) has also been referred to as insurance and investment models of reciprocity (Akiyama et al., Reference Akiyama, Antonucci, Campbell and Sokolovsky1997). An investment model is described when earlier transfers to the child were unconditionally returned and the insurance model describes when earlier transfers to the child were returned only in the event of parental need (Silverstein et al., Reference Silverstein, Conroy, Wang, Giarrusso and Bengtson2002). While several researchers have postulated that the support received by adult children from their parents earlier in their lives predicts filial support provision (Parrott and Bengston, Reference Parrott and Bengtson1999; Silverstein et al., Reference Silverstein, Conroy, Wang, Giarrusso and Bengtson2002; Raschick and Ingersoll-Dayton, Reference Raschick and Ingersoll-Dayton2004), others have argued that parents’ inter vivos transfers to adult children depend positively on the time those children spent assisting their parents (Kohara and Ohtake, Reference Kohara and Ohtake2011; López-Anuarbe, Reference López-Anuarbe2013), underlining the dynamic nature of reciprocity. Hsu and Shyu (Reference Hsu and Shyu2003) found evidence to support Cox and Stark's (Reference Cox and Stark1995) notion of preparatory reciprocity or preference shaping through demonstration which refers to the support or care provided by adult children to older parents in order to model or demonstrate this to one's own children, the expectation being that children will emulate them when the time comes. In a broader sense, family members exhibit serial reciprocity which involves a series of future-directed transfers that are motivated by obligations rooted in the past (Moody, Reference Moody2008; Isherwood et al., Reference Isherwood, Luszcz and King2016). Children initiate care-giving to their older parents only when they recognise the need though they are hypothetically prepared for such an eventuality reflective of in-principle reciprocity (McGrew, Reference McGrew1998; Wuest, Reference Wuest1998). When exchange partners recognise imbalances and non-reciprocity in the relationship, it leads to strain or sometimes the discontinuation of ties itself (Keefe and Fancey, Reference Keefe and Fancey2002; Reid et al., Reference Reid, Moss and Hyman2005; Verbrugge and Chan, Reference Verbrugge and Chan2008; Ugargol and Bailey, Reference Ugargol and Bailey2018). Reciprocity as a norm is a socially constructed element within a cultural context and guides the actions of individuals in the exchange relationship (Moody, Reference Moody2008). Many studies on reciprocity have quantitatively estimated material, time support, and care-giving costs and rewards between older adults, their spouses and children (Raschick and Ingersoll-Dayton, Reference Raschick and Ingersoll-Dayton2004; Leopold et al., Reference Leopold, Raab and Engelhardt2014; Isherwood et al., Reference Isherwood, Luszcz and King2016); however, very few have qualitatively explored care exchanges between older adults and their family care-givers (Hsu and Shyu, Reference Hsu and Shyu2003; Moody, Reference Moody2008; Funk, Reference Funk2012, Reference Funk2015; Ugargol and Bailey, Reference Ugargol and Bailey2018). Since qualitative inquiry is better suited to understanding the meanings attached to social exchanges (Raschick and Ingersoll-Dayton, Reference Raschick and Ingersoll-Dayton2004), we employ the social exchange theory to qualitatively explore reciprocity as a strategy of action that is culturally derived and socially implemented (Uehara, Reference Uehara1995; Hansen, Reference Hansen2004; Moody, Reference Moody2008). To achieve this aim, we focus our attention on older adults and family care-givers in emigrant households of India who will make sense of, account for and give meanings to their reciprocal exchanges through cultural lenses (Holroyd, Reference Holroyd2003).

Methods

Location

Data for this study were obtained through a qualitative study on exchange of care in emigrant households from a small town in the Kottayam district of Kerala, a southern Indian coastal state. Twenty-four emigrant households (where an adult child had emigrated to work abroad) where at least one older adult lived (aged 60 years and above) participated in the study. Left-behind older adults were the focus of this study and included those who currently required care and supervision as well as those who anticipated care needs in the future. The field site represented a large number of emigrant households and was part of the district of Kottayam where 24 per cent of households had faced an emigration event in 2011 (Zachariah and Rajan, Reference Zachariah and Rajan2012). Many of these emigrant households had more than one emigrant; a total of 23 sons and 13 daughters had emigrated from the 24 households that were included in the study. The range of duration since emigration of adult children was between one and 18 years. These families corresponded to the low- to middle-income groups and it was noted that many of the emigrant children returned home once a year during the annual Christmas holiday.

Ethics

The study was submitted for ethical approval and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board of the University of Groningen. Participants were informed about the study objectives and explained the interview process. After obtaining written informed consent to conduct the interviews and to audio-record the conversations, interviews were conducted at the convenience of the participants. Every participant understood that they could refuse to answer any questions or withdraw from the interview at any time. Pseudonyms have been used throughout the paper to provide context but not to link the participant.

Participant recruitment and profile

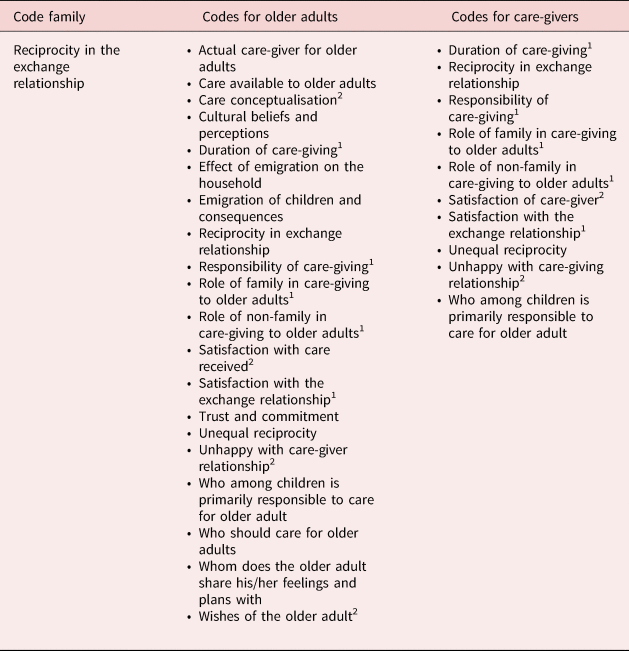

Older adults aged 60 years and above and having at least one emigrant adult child were selected. Left-behind older adults included those who required care and supervision currently as well as those who anticipated care needs in the near future. Care-givers were required to be primarily co-residing with the older adult but later expanded to include non-coresiding care-givers. The field site consisted of a large number of emigrant households. Given the safety concerns and vulnerability of older adults, it was felt inappropriate to knock on people's doors randomly to ask about the composition of the family. Moreover, since there were no available lists that we could access which described the household composition, snowballing was employed to recruit participants. The first group of participants were recruited during an interactive workshop organised for older adults by the Kerala Social Service Society, Kottayam. The researcher used this opportunity to briefly introduce his proposed research to the participants. Thereon, the researcher made contact with older adults and sought their consent to participate in the study. A possible limitation of this recruitment strategy was that only ambulatory older adults who attended the workshop could be recruited. Using a snowball technique where each participant helped identify another left-behind older adult in the neighbourhood, 24 older adults and their corresponding primary care-givers were approached and recruited for the study. Study participants thus included 24 older adults and their 24 care-givers (see Table 1). Among the 24 older adults, 13 were women and 11 were men. Older adults ranged in age from 60 to 82 years. Although information on income was not specifically collected, it was gathered through observations that these households corresponded to the lower- to middle-income class and only one of the participants did not own a home. All participants were native to the region and spoke Malayalam. Of the 24 care-givers, 11 were spouse care-givers (nine female spousal care-givers and two male spousal care-givers), eight daughters-in-law, two daughters, one son-in-law and two neighbours. Care-givers ranged in age from 31 to 73 years. Fourteen of the older adults were currently married and ten were widowed. The characteristics of older adult participants and their care-givers are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Description of older adults and their care-givers

Notes: UAE: United Arab Emirates. UK: United Kingdom. USA: United States of America.

Data collection

Between March and June 2015, 48 in-depth interviews comprising 24 older adults and 24 care-givers were conducted. Separate semi-structured in-depth interview guides were employed for both groups of participants. The first author conducted all interviews in the participants’ homes at their convenience. Each interview lasted approximately one hour and all the 48 interviews were conducted in Malayalam. The researcher employed the services of a local interpreter. Since the researcher could understand Malayalam and follow the conversations, he was able to probe the participants further through the interpreter. Older adults were asked to speak about their perceived care needs, the emigration event in their household, changes perceived post-emigration of their adult child and availability of care, and identify care-givers and talk about care exchange and mutuality in their relationship. Care-givers were asked to speak about their relationship with the older adult, understanding of the needs of the older adult, motivation to providing care and perceived mutuality in the care exchange process. Interviews were conducted up to the point of data saturation and the final sample consisted of 24 older adult–care-giver pairs.

Data analysis

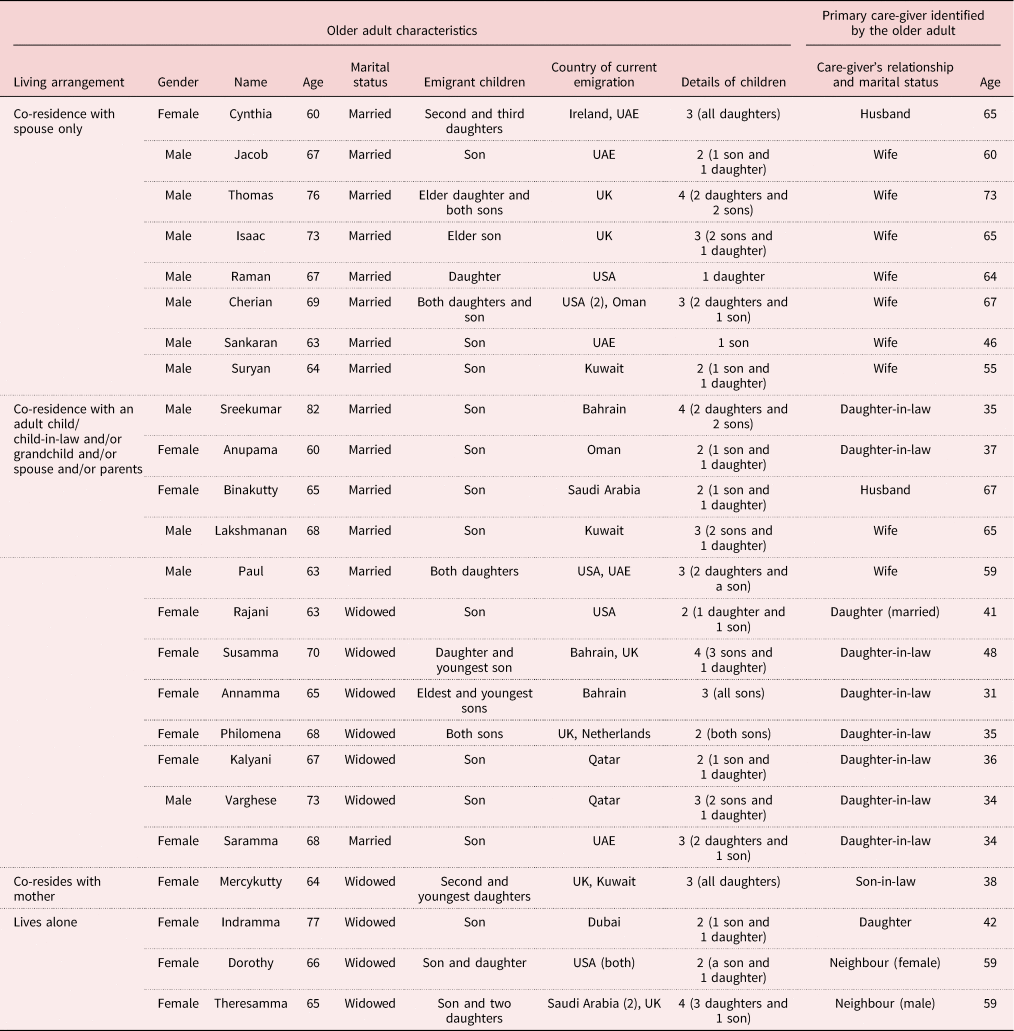

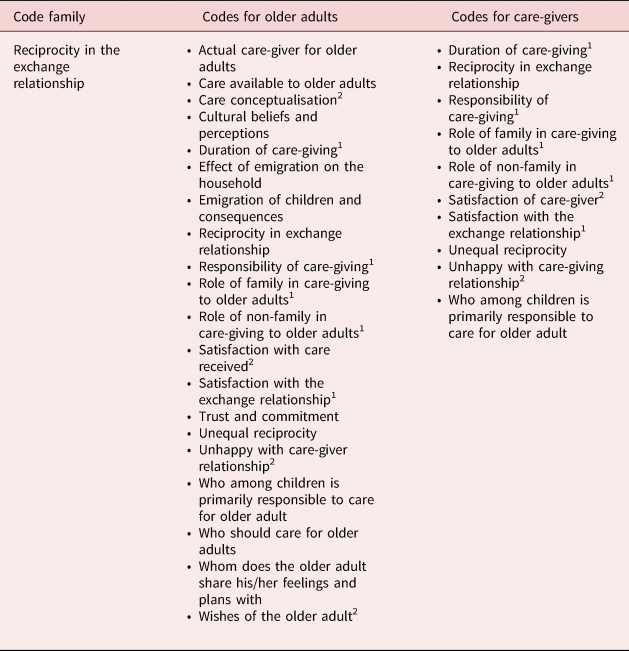

Qualitative data used for analytical purposes were derived from observations recorded, interview transcriptions and researcher's field notes. All taped interviews were transcribed verbatim into Malayalam (the language in the interviews) and then translated into English for textual analysis. Since the researcher could understand both languages well, cross-checks were done and the exact meanings of phrases from the original language were retained in the English version. The text was coded using Atlas.Ti version 7.5.10 R03 computer software. We analysed the data and explored the emergent theme of ‘reciprocity’ between older adults and their care-givers. Two cycles of coding resulted in primary and secondary codes. Refined codes and categories came up after multiple readings and re-examination of factual information and coded transcripts. Specifically, we have followed the following steps in data analysis: transcribing raw data verbatim, translating from Malayalam to English, immersion in the data, importing data into Atlas.ti 7, open coding, detailed line-by-line coding, identifying concepts, axial coding, reassembling open codes into sub-categories, selective coding, and integrating theories and literature (social exchange). Table 2 lists the code families and codes that emerged from the data analysis.

Table 2. List of code families and codes for older adults and their primary care-givers

Notes: 1. Congruent themes for older adults and care-givers which are discussed in the Findings section. 2. Non-congruent themes.

Findings

This study reports findings from analysis of qualitative data that describe the experiences of older adults and their care-givers in the care-giving relationship. The following six themes emerged which describe how participants defined and interpreted the support they provided and received as interpretive functions of reciprocity in care exchange: (a) one soul and two bodies, (b) filial obligations, (c) she is now the daughter of the house, (d) in-principle reciprocity, (e) children will do what they see us doing, and (f) experiences of non-reciprocity in care relationships.

One soul and two bodies

Spouse care-givers were the most common care-givers to older adults and the first theme describes the reciprocal nature of care exchange between spouses. More women were caring for their husbands as this was the norm within the local culture. Older couples described ingrained notions that the institution of marriage involves reciprocity and that it is a duty to care for each other through the lifecourse. Lakshmanan, an older male, described how he was motivated to provide care and affection to his wife, considering it as in reciprocation to the love and support he had received from her when she was younger and healthier. Here, past indebtedness is positioned as an appropriate motivation to current provision of care:

that's not a problem [to reciprocate the care], she's very loving and takes care of all my needs … she did everything for me. (Lakshmanan, older male, 68 years)

Spousal care-givers also referred to care-giving as a duty to highlight their motivation to providing care. Having seen previous generations provide care to older adults, Martha, a female spousal care-giver, felt it was her duty now to carry out the family tradition. Her question towards the end of the quote highlights the gendered expectations of care:

You have to do that as duty … I have not learnt from anyone in family … then my own parents were being cared for by my brothers and their wives, we've seen all that, no? then, we can't stay without taking care … would he allow me to be like that? (Martha, female spousal care-giver, 67 years)

Emigration of adult children had increased demands for spousal care-giving. Older adults were reconciled to the fact that expecting care from emigrant children was far-fetched as was with non-emigrant children who lived separately. Care exchange between spouses was the only possibility now and expectations of spousal care resulted from long-term attachment, co-residence and the notion that caring is a spousal responsibility:

Papa [husband] has the responsibility … there's nobody else … we only have each other, if I need something only he [husband] is around to take care. Will children leave their jobs and come? Even Sheila [daughter living in India] – can she drop her three children and come? (Cynthia, older female, 60 years)

Isaac, an older male, perceived that care-giving to spouses emanated from the love they had for each other and not from the notion of duty. He emphasised how ‘duty can be ignored but love cannot be ignored’ and recognised that the love he received from his wife is motivating him to support and care for her now:

After marriage she [wife] took care of me … because of love … if it's only duty, she can ignore it, but if its love she will have to … everyone is like that. (Isaac, older male, 73 years)

Trust and commitment enabled spouses to confide in each other and share thoughts and perceptions. Thomas, an older male who has been visually impaired for around three decades, narrates the mutual care between him and his wife and recollects a verse from the Bible which signifies the intricate bond between a husband and wife, that of one soul and two bodies:

When it's the wife, then we can share everything openly … but with children we cannot be so open and share … it has its own limits, right? … even in the Bible it says so, right?, you leave your parents and become one with your wife … one soul and two bodies … all that is true. (Thomas, older male, 76 years)

The long span of togetherness for most of these older couples meant that they knew exactly what their partner was going through. This familiarity and ability to read the requirements had enabled Joseph, a male spousal care-giver whose wife had been diagnosed with cancer, to provide her the much-needed courage in times of adversity:

She [wife] … she needs courage … she's always thinking that her death is very near, and like that … so she wants courage, that is why I'm giving her courage. (Joseph, male spousal care-giver, 65 years)

Though gendered stereotypes of care exist, male spousal care-givers were also seen caring for their spouses through supporting them in household chores. Negotiating cultural notions where men were labelled as breadwinners for the family and women as home-makers, male spousal care-givers reported no shame in contributing to household tasks:

Ever since I retired, we are always sharing our workload … ever since I retired I have been helping her … there is no shame in that. (Mohanan, male spousal care-giver, 67 years)

Though marital ties were affirmed to be underlying the motive to care for each other, reciprocity among spouses actually directed care-giving. Cultural expectations meant that women spousal care-givers were obliged to care as they were economically dependent on their husbands while the same norms did not apply to men. In India, beliefs around masculinity and masculine behaviour meant that male spousal care-givers had to overcome gender stereotypes to care for their wives. Mutual affection for each other and the ability to confide in each other were suggestive of trust and commitment which enabled reciprocal provision of care. The dynamics of power in the marital relationship along with cultural expectations come to the fore, which ascribe women to remain subservient to their husbands and thus be assigned to established care-giver roles.

Filial obligations

Care and protection offered by parents to their children in early life was justified by older adults to expect reciprocal return of care from children in later life. This theme is based on narratives of older adults and their care-givers who seemed to agree on the obligatory nature of care provision. Filial notions and responsibilities are reflected in these narratives, with children being expected and obliged to return the care. Annamma, an older woman, described that love that is given is returned as love and this rationalises the care exchange between parents and children:

Care or protection, I gave when they needed it … that is why they are also giving it back … if I say that, is it right? That is, when we give only then we get, can we say that? if we give we'll get that is the adage itself (smiles) … only when we give love do we get back love … that is how it is … if you give care you'll get care … that is how it is. (Annamma, older female, 65 years)

Another justification for reciprocal expectation of care was through the realisation of intergenerational transfers. Older adults positioned that since their assets and wealth would eventually be transferred to the children, mainly sons, an obligatory reciprocal expectation existed for the son to return the care. There is correspondingly lesser expectation from the daughter as she is traditionally considered not part of the household once she is ‘married into’ her husband's household. Since the daughter was less likely to benefit from intergenerational transfers, her obligation to care was less as well. Indramma, an older woman, captures this notion when she says:

Responsibility is that of my son only … our property and money everything is for him only, no? we have married off my daughter … I'm not stating the rule here … both of them take care but normally it is the son who should take care of the parents. (Indramma, older female, 77 years)

In Indian households, emigration of adult children, especially sons, suddenly disrupts carefully planned filial roles and expectations. Older adults have to abandon unrealistic expectations of emigrant children carrying out filial roles and instead rely on other non-emigrant children for their care. Daughters are also expected to come forth in such situations and provide care, although their limitations are known as they provide care for their parents-in-law too:

If the daughter can then she should, if the son can then he should … if it is a situation where son cannot as he is away, then daughter should do it. Both of them … we nurtured and brought up equally, right? So, it should be both, but since daughter is in another family, there may be limitations … to enquire after her parents-in-law. (Annamma, older female, 65 years)

In many households, older adults had not yet seen the reversal of care-giving roles and were yet to experience care-giving from the children. Older parents were continuing to provide care and supporting these households, even financially. Though daughters-in-law were expected to stay back and provide care to parents-in-law after emigration of the adult child, in a few households the daughter-in-law had also migrated with her husband, leaving older adults behind. Rajani's son had emigrated with his wife and since she was living alone, her daughter had moved in to co-reside with her. Rajani described her continued support to both children even today, even through financial support and asset transfers:

I give … whatever they need I'm doing for them and otherwise also I'm helping … then according to their wish I'm able to take care of them … in case of money I try and fulfil all their needs … when papa [husband] died we had 10–50 cents of land, that nobody was there to take care so barring this plot we sold everything and gave the money to both of them [son and daughter]. (Rajani, older female, 63 years)

Knowing that her mother was alone and pining for her emigrant son, Ramani, a daughter, had moved into her mother's household to co-reside and care for her. She narrates how her mother had begun to imagine health issues and illnesses and wished to visit the hospital very often when she lived alone, but now this tendency had reduced:

Here now amma [mother] is alone after papa's [father] death … since he [emigrant brother] also settled there [abroad] … I came here to give company to amma and as you grow older there are problems, loneliness … when amma is alone she is always thinking that she has some or the other illness … she wants to go to the hospital always … so now … it has reduced drastically … now she doesn't go much. (Ramani, daughter care-giver, 41 years)

Culturally established filial norms were motivators for expectation of care by older adults and for the provision of care to older adults by their children. Children of older adults perceived that they had to reciprocally return the care they had received earlier in life, drawing on notions of delayed reciprocity in action. Though all children had equal responsibility in care-giving, the child who was available through either co-residence or lived close to the older adult usually took on the responsibility. Due to the physical absence of the emigrant son, daughters often compensated and provided care to their parents in addition to care-giving responsibilities at their husband's household, although they were unlikely to be rewarded through bequests or intergenerational transfers.

She is now the daughter of the house

Older adults also perceived that filial care-giving roles were transferred to the daughters-in-law and sons-in-law once an adult child emigrated. The justification was that somebody had to take the place of the emigrant child and perform the care-giving role. Older adults invested in the transfer of filial roles to the daughter-in-law through recognising and welcoming the daughter-in-law as a daughter of the household:

Now to say the first person will be my daughter-in-law … now … between us? She's my daughter … I've only seen her like that. (Varghese, older male, 73 years)

She [daughter-in-law] knows that … I have not treated her with any difference as others … so just like she loves her mother. (Saramma, older female, 68 years)

Though daughters-in-law were preferred candidates for transfer of care-giving roles, older adults did acknowledge that she could face considerable limitations in her ability to provide care to the older adult on account of her multiple competing commitments in the household. Varghese, an older male, recognises that he can never expect nor demand the same degree of care from his daughter-in-law that he would get from his wife:

Can I ask my daughter-in-law to take care of me the way my wife did? She will have one, two or three children, she'll have to take care of them … take care of the house … then when all this is there, I can never demand the care that my wife would give me. (Varghese, older male, 73 years)

In a rare transfer of the care-giving role, an older adult was being cared for by her son-in-law in lieu of his wife who had emigrated. He had returned from abroad to care for his mother-in-law along with his child. This older adult had three married daughters, all of whom were away – two abroad and one living separately with her husband. Philip, the son-in-law, was married to the youngest daughter who had emigrated abroad. Philip narrated how he had come into the care-giving role, allowing his wife to pursue her career abroad and assume the role of the primary earner for the family. Philip felt that his care-giving role had made him privy to his mother-in-law's plans regarding assets and possessions, and he considered it a privilege to support her on these fronts. In the absence of male children, this son-in-law was a natural choice for being rewarded for care-giving through the transfer of assets from the older adult:

She used to talk to me and the elder one [son-in-law] … she won't discuss with the middle one … if anything I am there or she used to talk to her daughter, middle daughter … or second daughter … normally she used to tell me if she has some problem or property problem, she used to tell me since I'm here … I will sort that. (Philip, son-in-law care-giver, 38 years)

For daughters-in-law, assuming transferred care-giving responsibility was a process in itself. They had to sacrifice careers, bear separation from their husbands, and had to manage their child-care and household responsibilities together with care-giving roles for their parents-in-law. Daughters-in-law felt that caring for parents-in-law was their duty and perceived that the provision of care was in return for being accepted as a daughter to the household, attempting to reduce indebtedness incurred when parents-in-law offered love and support to their daughters-in-law. In our group of care-givers, all daughters-in-law, reported good relationships with their parents-in-law and this bonding was another reason daughter-in-law care-givers recognised as a motive to care-giving. The case of Elsa highlights this understanding:

I think just as a mother … my mother-in-law, my … uh … I have bonding with her … I think she also has the bonding … like a daughter she talks to me. Whatever she feels she tells me and I also tell her. I have nobody else to tell, only children are there so … I used to tell everything to her … it's a mental satisfaction, I feel happy, I feel peace in my mind that I've looked after my mother-in-law … uh … and that was my duty. (Elsa, daughter-in-law care-giver, 35 years)

Cultural obligations were so ingrained in daughters-in-law that they considered themselves completely responsible for the care of older parents-in-law in the absence of their husbands. The role of the emigrant son was often restricted to sending remittances and he was privy to only what was shared with him while the daughter-in-law shouldered the responsibility in the household:

Once I'm here, it is my responsibility … more than the son, it is my responsibility … to take care of them. My husband is not here, he sends the money and knows about only what we share with him … to see and do, that way most responsibility is mine. (Padma, daughter-in-law care-giver, 37 years)

Daughter-in-law care-givers positioned that the care they provide to their parents-in-law could be equated or balanced with the care that their parents would receive from their daughters-in-law, thus implying a generalised reciprocity notion to their care-giving motive transcending two households:

I feel happy because we should take care … whatever the challenges we will not stay without taking care of her … that's a decided thing … We'll take care … surely … only if I take care here will my parents be taken care of there, right? (smiles) (Ruth, daughter-in-law care-giver, 31 years)

Older adults perceived that post-emigration of their adult child, they could obtain care and affection from their daughter-in-law only if they invested in building the relationship through benevolence-raising gestures. Daughters-in-law felt indebted to the warmth and welcome from their parents-in-law and reciprocally took on the care-giving role under the weight of cultural expectations and the emigration event. While much theory states that reciprocity is a means to reduce indebtedness, serial processes in care-giving motivations are visible. Taking the care-giver son-in-law's case, the absence of male children in the household coupled with his provision of care to the older adult was building up his benevolence with respect to the older adult which could be reduced by the older adult through rewards such as the transfer of assets in time to come. Even daughters-in-law who shared no special bond with their parents-in-law felt that providing care to the older adult was in return for the care that her husband had received earlier, thus providing a generalised reciprocal motive to care-giving. Cultural stereotypes of how daughters-in-law enter into and handle care-giving roles are visible here. Care-giving daughters-in-law were essentially keeping alive the relationship between the older adults and the emigrant son, and the costs of care-giving today could likely fetch rewards through intergenerational transfers tomorrow.

In-principle reciprocity

Older care recipients perceived that the care they had provided to their children, daughters-in-law and sons-in-law would be returned when it was most needed, such as when they are unwell and require care. Similarly, care-givers were prepared to provide care when the care needs of older adults became evident. Older adults accepted the son's spouse as their own child in an attempt towards building trust and creating a support bank which could be availed of later. Through assisting and sharing in household work and treating daughters-in-law with love and affection, older adults such as Susamma hoped that daughters-in-law would be obliged to return the love and support when it mattered:

Since the daughters-in-law are at home … if we also treat them with love, they will feel our love and … more than taking care love is most important … they'll understand that we are unwell … they'll feel pity and will treat us with love and care (cries). (Susamma, older female, 70 years)

It was reassuring for many older adult participants that care and support is available in principle and would be provided to them when the need arose. Older adults often predicted their chances of receiving care from the daughter-in-law in future by observing their behaviour and experience over the lifecourse and perceived that the affection shown by the daughter-in-law was likely indicative of the care she would provide in future:

Towards us … son is not here, right? both of us are alone, she loves us very much … she doesn't go anywhere not even her own home, she would just go quickly and be back soon … we know … from her behaviour that she cares for us … it is the same even for us … it is still the same … since 15 years. (Anupama, older female, 60 years)

Sreekumar, an 82-year-old man, hopes that his emigrant children would come down when he is unwell and take care of him or support him through others, underlying the presumption that care would be available when required:

Even those who are not here they will come. If there is any need they will come and stay at the hospital … if they can't do it by themselves then they will also pitch in. (Sreekumar, older male, 82 years)

Care-givers on their part also expressed similar notions of being prepared to provide care in the event increased care needs of the older adult became evident. They were in principle prepared and ready to provide active care and support in return for the care they had received from the older adult. This also included being prepared to incur costs such as giving up a job or career to be around at home to care for the older adult – a cost that had to be borne to effectuate reciprocity:

Now, my job … if amma [mother-in-law here] is totally unwell and there's nobody in the family then definitely I must stop my job. That, otherwise also once they grow more aged I've decided to stop my job. (Lucia, daughter-in-law care-giver, 34 years)

Maria, a daughter-in-law care-giver, however, described that in the event of increased care requirements for the older adult, it would not be possible for one person to take on the entire responsibility and she expected all members of the family, especially those living with the older adult, to shoulder the efforts together:

…if ammachi [mother-in-law here] is unwell, totally bed-ridden, since the other children are not here, no? then I, my husband and children should take care of her … everyone should do it … there is no point in only one person taking care … everyone should pitch in … If they are close by then they too should pitch in, but mainly it is the responsibility of the members living at home … that is what I believe. (Maria, daughter-in-law care-giver, 48 years)

These narratives provide us with perspectives on in-principle care availability and the effectuation of care when care needs are established. Care-givers, who had benefited from the affection and care provided by the older adult, were in-principle willing to provide reciprocal care when increased care needs due to, for example, illness, hospital visits or intensive home care requirements became apparent. This theme identifies well with the notion of in-principle reciprocity. However, when care needs increased for the older adult, it translated into costs for care-givers such as sacrificing careers or giving up other competing roles. Incurring these costs was also a mechanism for reducing the indebtedness in the care exchange relationship.

Children will do what they see us doing

Participants also interpreted care-giving to older adults as a family responsibility which continued in reciprocal cycles from generation to generation. Older adults and care-givers perceived that caring for older adults was also a means to demonstrate that care-giving to older adults is the right thing to do and the benefits of this demonstration were perceived to be that the children who observed care-giving would emulate their parents when their turn to provide care came up. Anupama, an older adult, felt it is better this notion is ingrained early in life for children as she perceived that when sons grow up and get married, they tend to listen to their wives and could end up neglecting their parents:

…generally now if children do not take care you feel sad that parents did so much and now how the children are not looking after them … they nurtured them with so much love and now they don't even look back after marriage they listen only to their wife. (Anupama, older female, 60 years)

Older adults considered care-giving to older parents as an act that ought to be observed in a family, internalised and enacted by the children later. The costs that would go into care-giving were synonymous with the rewards that would accrue later in life. Older adult participants perceived that by not demonstrating care-giving, implying not providing care to older parents, actually meant that no care would be available to them when it is needed:

When we grow old we should get some protection, right? If we don't take care … our children will also do the same. That is what I'm thinking … If I don't look after my mother, then there'll be no one to look after me. (Mercykutty, older female, 64 years)

It was similarly described by care-givers that if they failed to care for their spouses or parents, there would be no one to look after them when they needed care. Care-giver motivations to care-giving were characterised by the obligation to care as an investment in the anticipation that the care provision to them in later life would be on the same lines, as their demonstration or non-demonstration of care-giving is likely to be replicated by their children:

If I don't take care of mummy, I get angry with her, shout at her then my child grows up seeing all that, no? So if I talk like that won't this child talk like this tomorrow? So, if we speak well the child also learns well and speaks the same. (Ruth, daughter-in-law care-giver, 31 years)

Care-giving to older adults was thus positioned as a cost that had to be demonstrated to children in the expectation that care or rewards would be returned to them in a similar fashion at a later date. This expectation of care from their children was enacted through demonstration of care-giving as a means to shape children's behaviour and instil similar reciprocal motives. Using the tenets of the norm of reciprocity, we see that care-givers were willing to bear costs today in return for rewards through receiving care from their children at a later point in time. On the converse, care-givers recognised that if they failed in demonstrating the act of care-giving to their children, the children were likely to refrain from providing them reciprocal care, signifying the cyclical or serial nature of reciprocity.

Experiences of non-reciprocity in care relationships

Instances of non-reciprocity also emerged from the narratives of older adults and their care-givers. Participants spoke of deficits in what they expected and what they received from the children. Though older adults expressed that they did not expect the children to return the debt, they still harboured hopes of receiving the care. Isaac has had a hard life – due to disability he had to give up his job and his second son became an alcoholic. While all his hope now rests on the emigrated son, he feels his debt is yet to be repaid:

If I bring up my children with care and protection … the children too have the right [duty] to take care of me in the same sense … that they should understand … there is no expectation but they have a debt to fulfil … to do it … so I'm not expecting that debt … I don't have that what I did to them, they must do to me … I want them to do … but it is only a desire. (Isaac, older male, 73 years)

We also came across instances of intentional neglect of parents. Emigrant sons had not returned home for years together and the burden of care was largely borne by the spouses and daughters-in-law. The older adults felt pained by the absence of migrant children and perceived that those who emigrate will often forget their responsibilities back home. Imbalances in reciprocity often led to frustrations and conflicts in the care-giving relationship. Some of the older adult participants had misunderstandings with their care-givers and often relied on divine consolation as a coping mechanism to avert outright friction within the household.

Philomena is 68 years old and a widow. She has two sons who have emigrated and currently lives with her daughter-in-law and grandchildren. Her daughter-in-law, Elsa, decided to return to Kerala from abroad with her children to take up a job at a local college. Her busy schedule with the job, children and caring for her mother-in-law gives her little time for anything else. Philomena does not appreciate her own current situation as she is financially dependent on her daughter-in-law and her social activities depend on the time Elsa has to spare for her. The change in power relations in the household creates much grief but Philomena refuses to confront it, as she has nowhere else to go and no resources of her own.

Elsa is 35 years old and was living in London with her husband and three children. She completed her PhD while in London. When her father-in-law passed away it was decided by her husband and his brother that she would go back to live with her mother-in-law (Philomena). In this way, she can continue to work and Philomena can help care for her three children. On her return, Elsa realised that she had to take over the role as the head of the household and run the house. Her job at a local college, three children and managing a house has left her with little time to give exclusive care to Philomena. Elsa also expected Philomena to care for her children but that was not the case. Elsa sometimes has to be harsh towards Philomena on what she can do for her. Elsa hopes her husband will return and share the burden of managing the house and caring for Philomena.

There were also misgivings that older adults spoke of on account of children not taking the feelings of the older adult seriously or failing to recognise the needs of the older adults. Rajani is 63 years old, a retired school teacher. Her son has emigrated with his family and when her husband passed away, her daughter (including her children) decided to come to live with her. Rajani contributes a lot to the household but perceives that she receives much less care:

…there are times when that closeness is needed … both my children think that I do not need any care … that I'm not that old, they think I can live on my own … that's how both of my children think … (pause) but in my mind I have some fear … but my children do not think about me that much … I still have a ‘childhood’ remaining is how my children think … maybe because I do things very fast they think, I go wherever I have to go alone. (Rajani, older female, 63 years)

Spouse care-givers who were providing care to their husband also had reservations regarding who would care for them when they themselves needed care since all the children had moved away from the household. Nirmala was providing care to her husband, Suryan, ever since he met with an accident and lost his limbs. She felt she had done her duty but was unsure if there would be anyone around when she would begin requiring care:

This many people have told me … ‘you should be worshipped’, everyone who sees me says that, whoever sees that … those who know us from early days … they've only seen this, no? for 10–20 years [he] has been bed-ridden after the accident, if it was anybody else, they won't even look after for 20 days let alone 20 years, they say … either they would admit to an orphanage or say I can't do it and walk out … what can they not do? I've not even thought about it in that situation … that is each person's this … now who will take care of me? That is the question … (laughing) … well, I'm taking care … anybody else will take care I cannot say … (smiles) … they're not here … that's all … mmm. (Nirmala, spouse care-giver, 55 years)

Reciprocity thus was not always uniform and balanced. There were instances of imbalance and sometimes non-reciprocity too from these narratives. Imbalances in reciprocity often led to the perception that care-giving is a burden from which nothing beneficial in return could be expected. Often care-givers did not expect reciprocal care from the older adult but from others around in the expectation that their care-giving act would be appreciated and rewarded in return; however, this was not assured. Imbalances of many types were expressed – some related to children not recognising needs, having no intention to care for their parents, and some instances where children took care at their convenience which was not appreciated by the older adult. Non-reciprocity in the exchange relationship threatened the relationship and often led to frustrations and friction between the older adult and the care-givers, thus compromising the wellbeing of the older adult and care-givers perceiving increased burden.

Discussion

The findings or themes from this study in themselves reflect the meanings and interpretations that older adults and their care-givers ascribed to reciprocal support exchanges in their relationships. These reciprocal notions provided an interpretive framework that help explain expectations, motivations and experiences given the nature of relationships, participant characteristics and the cultural context. The study integrates previous research on reciprocity and contributes to understanding how reciprocal support in families explains older adult care.

Older adults we worked with in these emigration households of Kerala find their current social milieu very different from anything they had expected; however, their wishes for reciprocal family relationships and their efforts to sustain them persist through the interviews (Ugargol and Bailey, Reference Ugargol and Bailey2018). Care-giving motivations and reciprocity between spouses were described as being shaped by mutual affection and responsibility, and an obligation built on the institution of marriage itself. Older couples believed that marriage involves reciprocity and mutual support, and hence caring for each other was considered an integral part of being married (Carruth, Reference Carruth1996; Call et al., Reference Call, Finch, Huck and Kane1999; Leopold et al., Reference Leopold, Raab and Engelhardt2014). The ability to confide in each other was reassuring and encouraging for older spouses, indicative of the trust they had in each other. Studies have indicated that if spouses felt that they had nobody to confide in to help them understand their current status or to express care and affection, it could affect the context of the exchange relationship itself and result in negative evaluations (Call et al., Reference Call, Finch, Huck and Kane1999; Isherwood et al., Reference Isherwood, Luszcz and King2016). While women had to carry out care-giving obligations that were culturally shaped, male care-givers had to overcome gender stereotypes to care for their wives and parents-in-law but did so without any cultural or societal expectations. They demonstrated that by not being ‘ashamed’ in the care-giving role, they experienced feeling a sense of purpose without any burden of expectations (Ribeiro et al., Reference Ribeiro, Paúl and Nogueira2007; Isherwood et al., Reference Isherwood, Luszcz and King2016).

Older adults frequently referred to reciprocal expectations of care and support from their children in return for the love and affection provided to them in nurturing and bringing them up earlier (Dykstra and Fokkema, Reference Dykstra and Fokkema2007). This perception finds resonance in literature on intergenerational care and transfers which posit that in Asian and South-East Asian societies, reciprocity within families is strongly normative and that older adults expect to co-reside with at least one of their children, harbour expectations of filial support, and tend to rely on them for financial and daily assistance (Knodel et al., Reference Knodel, Chayovan, Siriboon, Hareven and Gruyter1996; Biddlecom et al., Reference Biddlecom, Chayovan, Ofstedal and Hermalin2002; Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Rowe and Pillai2009). Though adult children often find difficulty in using the construct of responsibility to describe the support they provide for ageing parents, ambivalence has been related to symbolic associations of the construct with obligation and burden (Funk, Reference Funk2015; Ugargol and Bailey, Reference Ugargol and Bailey2018) and children care-givers often referred to ‘filial concerns’ when they recognised the need of their older parents (Funk, Reference Funk2012, Reference Funk2015; Ugargol and Bailey, Reference Ugargol and Bailey2018). Recognising the needs of the older parent was the first step in beginning to reciprocate care to ensure the wellbeing of the parent (Cicirelli, Reference Cicirelli2000), and the needs of parents obliged their adult children to reciprocate and act out their filial duties (Miller, Reference Miller2003). Care-giver participants also recognised reciprocity over time-lags and identified themselves as filially responsible children towards their parents which relates to the notion of delayed reciprocity (Funk, Reference Funk2008). Delayed or ‘lagged’ reciprocity is the event when the provision of support to older parents was to fulfil an obligation to repay a social debt based on that parent's earlier transfers to the child. Though older adults perceived their sons to be primarily responsible for their care, they also noted that in the absence of the emigrant son, the responsibility of care provision is shared with the other children including the daughters (Dharmalingam, Reference Dharmalingam1994; Miltiades, Reference Miltiades2002).

Cultural models and living arrangements of older adults obligate daughters-in-law to provide care to parents-in-law in the Indian context (Bongaarts and Zimmer, Reference Bongaarts and Zimmer2002; Lamb, Reference Lamb2013). In an emigrant context, where the absence of the emigrant son leads to the transfer of care-giving roles, daughters-in-law who had no previous benevolence-raising exchanges with the older adult counted on the warmth and affection received from the older adult in calculating their motivation to care for the older adult (Jamuna and Ramamurti, Reference Jamuna and Ramamurti1999; Hsu and Shyu, Reference Hsu and Shyu2003), along with attempting to reciprocate for the care provided by the older adult to their husbands earlier. Daughter-in-law care-givers also recognised that demonstrating care-giving to older adults was an investment for the future since children were observing the provision or non-provision of care to the older adult in the household and could end up emulating the same. This is similar to what Hsu and Shyu (Reference Hsu and Shyu2003) reported from a study in Taiwan. Daughter-in-law care-givers also equated the care they provide to their parents-in-law with the care that their parents would receive from their daughters-in-law, indicative of a generalised reciprocity notion to care-giving (Bearman, Reference Bearman1997; Moody, Reference Moody2008).

Non-emigrant children, especially daughters living in another household, felt that they were also responsible for the care of the older parent and had to reciprocate past assistance although they did perceive that the son is primarily responsible. Family members attempt to reciprocate past help and count on future assistance so that they do not have to maintain balanced exchange relationships at any single point in time (Antonucci, Reference Antonucci, Binstock and George1990; Ugargol and Bailey, Reference Ugargol and Bailey2018), and family reciprocity and support exchanges continue even in a modernising society (Verbrugge and Ang, Reference Verbrugge and Ang2017). This explains why children help older parents after having received varied kinds of support and assistance early on in life. The findings contend that while daughters were more likely to take on greater parent-care roles when adult sons emigrated, their efforts try to accommodate both the needs of the parents as well as their own children and the multiple commitments they handle. This finding depicted cultural models and expectations that daughters ascribed as their motivation for caregiving (Wolf et al., Reference Wolf, Freedman and Soldo1997; Verbrugge and Ang, Reference Verbrugge and Ang2017; Ugargol and Bailey, Reference Ugargol and Bailey2018). Exchange perspectives abound in Asian care-giving literature, e.g. in Indonesia being a daughter, older, emotionally close to the mother, having supported the mother in the past, being perceived as future bequest receiver and being geographically in close proximity to the mother increased the chance of being selected as the preferred future primary care-giver (Surachman et al., Reference Surachman, Edwards, Sweeney and Cherry2018). Thus, older adults as well as their family care-givers interpreted continuity or the cyclical nature of reciprocity and invested in future-directed support exchanges that were motivated by obligations raised in the past (Hsu and Shyu, Reference Hsu and Shyu2003; Funk, Reference Funk2008, Reference Funk2012, Reference Funk2015; Moody, Reference Moody2008).

When imbalances or non-reciprocity were noted by older adults or their family care-givers, it challenged goodwill and threatened the continuation of the care-giving relationship (Verbrugge and Chan, Reference Verbrugge and Chan2008; Verbrugge and Ang, Reference Verbrugge and Ang2017). Many care-givers who report non-reciprocity and frustrations in relationships also feel that they give more to the other person than they receive in return (Ugargol and Bailey, Reference Ugargol and Bailey2018). While care provision does appear to follow cultural notions and expectations, they seem to be of lesser significance when it comes to long-term and deep-rooted interpersonal relations between older adults and other members of the family (Datta et al., Reference Datta, Poortinga and Marcoen2003). Thus, even when norms of obligation are strong, the needs of the care receiver may exceed the care-giver's capacity for care provision, which can result in a negative evaluation of the relationship itself (Call et al., Reference Call, Finch, Huck and Kane1999; Funk, Reference Funk2012; Ugargol and Bailey, Reference Ugargol and Bailey2018). In similar contexts in China, older adults living in internal migrant families reported financial worries whereas those living in transnational families worried about lack of care (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Liu, Xu, Mao and Chi2018). It is worth noting how socially embedded relationships tend to build trust and commitment as harbingers to reciprocal exchange and when that fails, reciprocity is in question.

The findings from this analysis of qualitative accounts provide insights into how older adults and their care-givers implicitly and explicitly recognised, interpreted and described reciprocity in their obligations, responsibilities, duties and actual care-giving, and invested in care-giving to avail rewards later. We have been able to improve understanding of how older adults and family care-givers rely on reciprocity in their care exchange relationships, especially in an Indian emigrant context where culture and gender play a significant role. These findings resonate with the need to pay close attention to the increasingly transnational and at the same time contextual places within which ageing and aged care now routinely takes place in a globalising world (Wilding and Baldassar, Reference Wilding and Baldassar2018). While some of the findings find congruence in the work of fellow researchers, this study improves contextual understanding of reciprocal motives that govern care exchange in family relationships within emigrant households.

Limitations

The findings of this study are limited to the experiences and characteristics of the older adults and their care-givers living in emigrant households of Kerala. The cultural norms of the region together with religious beliefs could have influenced the understanding and interpretation of their roles, responsibilities and notions within the care exchange relationship. We have relied on personal constructions of reciprocal exchanges and linked them to the theoretical framework. The extent of reciprocity that is expected and enacted in care-giving relationships might, however, vary across cultural settings.

Implications

More broadly, the paper contributes to research on ageing in a socio-cultural context with emigration as the backdrop. Specifically, the paper provides three major insights. Firstly, the paper signals the call to move beyond existing notions of reciprocity as motivating factors for support and instead relies on how individuals interpret reciprocity in their care exchange process, fluctuating often between immediate dyads and reciprocal exchanges between generations. Secondly, while in an Asian society such as India, filial roles are evident and there exists the underlying norm that adult sons are expected to co-reside and care for their older parents, emigration has violated the traditional role from being played out and has transferred the filial responsibility back to women – daughters-in-law, spouses or other non-emigrant children. Thirdly, though family care-givers and older adults interpreted continuity or the cyclical nature of reciprocity and provided support exchanges that were motivated by obligations raised in the past, unequal reciprocity or non-reciprocity were interesting counter-normative findings that reflected imbalances in the exchange relationship. We also see glimpses of adaptive forms of co-residence (son-in-law moving into a care-giving role while the daughter of the older adult emigrates) and intergenerational support (daughter moving in close proximity such that the older parent could be supervised) which are visible in other emigration contexts too where emigration disrupts the filial continuity of care.