Introduction

Most scholars today would agree that the transition from active work to retirement is a complex and dynamic process during which individuals’ motivation and preferences vis-à-vis work are in continuous interplay with various contextual factors at different analytical levels. Research has demonstrated that the configuration of welfare state provisions and incentive structures in old-age pension and early retirement programmes have a large impact on the levels of work participation in late age (Kohli et al., Reference Kohli, Rein, Guillemard and van Gunsteren1991; Ebbinghaus, Reference Ebbinghaus2006; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Dorey, Chaffee and Sonnega2016). Generous benefit programmes may attract employees and pull them to exit the labour market early. In consequence, many nations, including Sweden, enforce stronger work incentives in old-age retirement programmes in order to reach the widespread policy goal of extending working life. Another common policy measure is to abandon fixed statutory retirement age and replace it with a flexible age interval.

In Sweden it is, from 2020, possible to take an old-age pension from the age of 62 to 68, at the latest. The national public pension is a contributory system which means that pension levels depend on incomes throughout the whole life, on occupational pensions and on private savings. To stimulate late exit from the labour market, the system is incentivised so that taking a pension before the age of 65 implies a reduced level of pension income while withdrawal from work after 65 gives annually a 7–8 per cent increase in pension income (Socialdepartementet 2016).

Even if labour force participation rates indeed have increased during the past decades, the growth of qualitative labour shortages are becoming one of the more problematic consequences of population and workforce ageing. In Sweden, and in many other western countries, both the private and especially the public sector are experiencing difficulties in finding and hiring employees with required skills and competences profiles (Arbetsförmedlingen, 2016). The Swedish welfare sector employs 1.2 million people and projections suggest that almost 300,000 of those will be leaving work due to retirement by 2026 (Sveriges kommuner och landsting (SKL), 2018). When future increased welfare service demands are accounted for, the sector needs to recruit more than 500,000 new employees in the coming six years. The current levels of labour shortages may thus jeopardise the prospect of maintaining proper quality levels and accessibility in welfare services and provisions. In this context, older workers are becoming more valuable to employers (Rice, Reference Rice2018) and retaining qualified employees in late age in continuous work is one way to meet the challenge of sustainability in both welfare services and labour supply. Employers have also, to an increasing extent, started to view older employees as an important staff resource that may alleviate the negative effects of lack of needed skills and competencies (Wang and Shultz, Reference Wang and Shultz2010; SKL, 2018).

Research in the area of retirement timing has to a large extent focused on macro- and micro-level explanations, i.e. the influence of the design of old-age pension and early retirement programmes, and how lack of work incentives in these programmes tend to pull out employees from work. Micro-level studies have concluded that individual health (physical, cognitive and mental) and health-related behaviour, as well as psychological factors such as personality, motivation, preferences and attitudes, are all of importance, as is gender, ethnicity, education, social position, economic status, family, domestic and household factors, as well as a person's ability to work (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound), 2012; Hasselhorn and Apt, Reference Hasselhorn and Apt2015; Vickerstaff, Reference Vickerstaff, Hasselhorn and Apt2015; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Dorey, Chaffee and Sonnega2016; Gyllensten et al., Reference Gyllensten, Wentz, Håkansson, Hagberg and Nilsson2019). It is less common with studies that focus on meso-level factors and especially the role of workplace conditions and how workplace or organisational factors may obstruct or facilitate work late in life (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhan, Liu and Shultz2008, Hasselhorn and Apt, Reference Hasselhorn and Apt2015; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Dorey, Chaffee and Sonnega2016, Krekula, Reference Krekula2019). In this context, it is important to further the understanding of what drives older employees in their decisions to retire or to keep on working. Such knowledge is also important for employers’ possibilities to design relevant strategies and interventions that may enable workers to remain active in the workforce in late age (Armstrong-Stassen and Ursel, Reference Armstrong-Stassen and Ursel2009; von Bonsdorff et al., Reference von Bonsdorff, Huuhtanen, Tuomi and Seitsamo2010; Truxillo et al., Reference Truxillo, Cadiz and Hammer2015; Veth et al., Reference Veth, Emans, Van der Heijden, Korzilius and De Lange2015).

Against this background, the aim of this study was to explore retirement preferences among employees (aged 55 and older) in a large Swedish health-care organisation and to identify work-related motives influencing retirement preferences. The health-care sector in Sweden, as well as in many other countries, is heavily strained and exposed to the loss of valuable competencies due to retirement while at the same time experiencing urgent qualitative labour shortages (European Hospital and Healthcare Employers’ Association (HOSPEEM), 2013; Taneva et al., Reference Taneva, Arnold and Nicolson2016; SKL, 2018; Gyllensten et al., Reference Gyllensten, Wentz, Håkansson, Hagberg and Nilsson2019). Prognoses point out that increased educational volumes and recruitment of new graduates will not be sufficient means to fill the shortfalls (Norrlandstingens regionsförbund, 2013). Studies in this field of research is dominated by quantitative studies of organisations (Hasselhorn and Apt, Reference Hasselhorn and Apt2015; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Dorey, Chaffee and Sonnega2016). This study contributes to the research area by means of analysing qualitative data, scrutinising older employees’ own descriptions and experiences of how workplace conditions affect their thoughts on the timing of retirement, and how this is related to both early and late preferences in a mixed occupational context.

Retirement preferences, retirement intentions and timing of retirement

Timing of retirement is indeed a complicated matter and there are several conceptual frameworks trying to capture this complexity (e.g. Beehr, Reference Beehr1986; Wang and Shultz, Reference Wang and Shultz2010; Feldman and Beehr, Reference Feldman and Beehr2011; Nilsson et al., Reference Nilsson, Rignell-Hydbom and Rylander2011; Hasselhorn and Apt, Reference Hasselhorn and Apt2015; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Dorey, Chaffee and Sonnega2016). When put together, a dynamic process becomes apparent where different factors from different welfare domains and analytical levels operate in a social and economic context over time.

The conceptualisation of retirement decisions as a process stresses not only the actual decision-making process that precedes full retirement, but also a ‘lifecourse perspective’. This implies that retirement is thought of as determined by exposure to factors both early and late in life, where ‘long-term influences’ of early elements, such as social origin, education, etc., interact with later manifestations, such as health, qualification, motivation and ability to work (see e.g. Loretto and Vickerstaff, Reference Loretto and Vickerstaff2012; Hasselhorn and Apt, Reference Hasselhorn and Apt2015; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Dorey, Chaffee and Sonnega2016; Solem et al., Reference Solem, Syse, Furunes, Mykletun, De Lange, Schaufeli and Ilmarinen2016). During this dynamic process, various advantages and disadvantages are accumulated and contribute to shape an opportunity structure that provides individuals with different sets of opportunities and constraints (Silverstein and Giarousso, Reference Silverstein, Giarusso, Settersten and Angel2011; Örestig et al., Reference Örestig, Strandh and Stattin2013).

Further, during the decision-making process leading up to retirement, people's retirement intentions and deliberations can be placed on different levels of firmness depending on how well the intention can be expected to predict an actual exit from the labour market (Solem et al., Reference Solem, Syse, Furunes, Mykletun, De Lange, Schaufeli and Ilmarinen2016). Reaching a decision, the highest level of firmness on when to retire normally requires planning and numerous factors are taken carefully into account. Once a decision is taken, the employee's mind is made up and the probability of revoking such a decision is limited. Retirement preferences, on the other hand, hold a substantial degree of flexibility and are less rigid than a decision yet to have a significant predicting power on actual retirement behaviour. Preferences take into account the personal wish of when to retire, often specified as a certain year of age. In addition, preferences are exogenous and thus influenced by external factors and are adaptable to situational circumstances such as economy, limitations due to health, available pathways into retirement, etc. (Lukes, Reference Lukes2005). Retirement may thus be postponed by limiting people's choices and/or by influencing their retirement preferences (e.g. Feldman and Beehr, Reference Feldman and Beehr2011; Halleröd et al., Reference Halleröd, Örestig and Stattin2013). Preferences can therefore be considered as being specifically suitable for, and responsive to, workplace interventions targeted at prolonging older workers’ careers.

Employees’ preferences as well as actual retirement timing may be affected by a large number of various factors. In research, such factors have been conceptualised in terms of push, pull, stay, stuck and jump (Kohli et al., Reference Kohli, Rein, Guillemard and van Gunsteren1991; Andersen and Jensen, Reference Andersen and Jensen2011). Push factors refer to environmental circumstances that force employees to leave work and the work withdrawal is thus considered as involuntary. Age discrimination, poor working conditions or obsolete skills are examples of push factors. Pull factors explain retirement timing as a consequence of generous and easily accessible welfare and social insurance programmes which are economically attractive to older workers. Stay factors highlight circumstances at work that make continuing work attractive for older workers while stuck refers to factors that force workers to stay on, irrespective of the individual's own preferences. Jump is a concept that brings forward the importance of social norms and how, for example, the trade-off between work and leisure time is valued. These concepts clearly represent different types of explanatory mechanisms in relation to timing of retirement. In reality though, all these factors are likely to interact in the retirement decision (Andersen and Jensen, Reference Andersen and Jensen2011).

When looking at factors at the organisational level, there is growing empirical evidence of the importance of working conditions in relation to the retirement decision process (von Bonsdorff et al., Reference von Bonsdorff, Huuhtanen, Tuomi and Seitsamo2010; Moreira et al., Reference Moreira, Azevedo and Manso2018). This concerns both physical and psycho-social work environments. Poor work environments may directly affect employees’ health and functional capacity, and thus work as a push mechanism forcing employees out of work (Stattin and Järvholm, Reference Stattin and Järvholm2005; Siegrist et al., Reference Siegrist, Wahrendorf, von dem Knesebeck, Jürges and Börsch-Supan2006). Working conditions also affect employees’ job satisfaction and motivation, which in turn may be important for retirement behaviour and can, when perceived as positive, serve as a stay factor (Siegrist and Wahrendorf, Reference Siegrist and Wahrendorf2010; Andersen and Jensen, Reference Andersen and Jensen2011).

Another important aspect of workplace characteristics concerns the behaviour of the employers and to what extent older workers’ needs are recognised and regarded as important.

Research has demonstrated that people change both physically and psychologically with age. However, age-related changes differ substantially at an individual level. For some individuals, changes are profound while others experience only minor changes (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Olson and Shultz2012; Taneva et al., Reference Taneva, Arnold and Nicolson2016). Older workers may also take advantage of broad knowledge and experience in compensating for cognitive decline. According to Taneva et al. (2016: 397), a lot of the age-related changes are quite limited and possible negative effects may be ‘reduced by a supportive environment’.

Today most scholars would agree that ambitions to retain older workers therefore need to include practices and procedures aimed at promoting older employees’ work abilities (Ilmarinen, Reference Ilmarinen2006). Research in this area has grown during past decades and a number of studies have demonstrated that individual adjustments in working conditions (I-deals) are of great importance in order to facilitate work in late life (Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, Slater, Chang and Johnson2013; Oostrom et al., Reference Oostrom, Pennings and Bal2016). I-deals, or idiosyncratic deals, take as an important point of departure the large heterogeneity in the old-age population. Instead of formalised age-management strategies, I-deals are informal and individually negotiated measures between employers and employees, and thus designed to meet individual needs.

However, only a minority of employers have introduced sustainable age-management policies and/or have well-developed human resource (HR) strategies in place targeting older workers. Scholars have also noted that there is a need for improved knowledge about how employees themselves value various HR practices and how they may fit specific and individual needs (von Bonsdorff et al., Reference von Bonsdorff, Huuhtanen, Tuomi and Seitsamo2010 ; Kooij et al., Reference Kooij, Jansen, Dikkers and de Lange2014).

Method

Data material

The health-care organisation under study is the main provider of health care in a northern region in Sweden and has more than 10,000 employees. Like many other health-care organisations, they experience a shortage of staff and especially key skills such as specialised nurses and medical doctors in certain areas, and even greater shortages are anticipated in the near future. One solution, besides employing new and newly trained staff, is to retain older employees. In order to study the employee's motivation to work in late age, a questionnaire focusing on retirement preferences and working conditions was distributed to all employees aged 55 or older. Retirement preferences were studied through the question: ‘Based on today's prerequisites, at what age would you like to retire?’, where the respondents were asked to fill in their preferred age for retirement. Respondents were also invited to describe their motives and reasoning for their chosen preference by giving free-text answers. The qualitative data from these free-text answers constitutes the core empirical base in the present study.

In total, 2,152 employees participated in the questionnaire, constituting a response rate of 72 per cent. An analysis (not included here) of the responding group and the sample frame show only very minor differences concerning sex, age and occupation, which means that the respondents are representative of all employees in the organisation. Out of the 2,152 survey participants, 534 individuals chose to state supplementary free-text answers about their motives for a chosen retirement preference. These answers included both work-related and non-work-related motives, and in many cases were extensive and detailed. Given the aim to deepen the understanding of how employees relate working conditions to their retirement preferences, the analyses are based on primarily work-related motives. Answers relating to health and financial issues have been included as frequently they are linked to work or the organisation, while answers not explicitly linked to work, e.g. ‘taking care of relatives/grandchildren’, ‘retiring together with spouse’ or ‘more leisure time’, were excluded in the analysis. Therefore, the final qualitative sample consisted of work-related free-text answers from 321 respondents.

Variables and analysis

As a first step of the analyses, we present descriptive statistics on the retirement preferences for all who participated in the survey. We present preferences in mean values for various groups of employees. This concerns the demographic variables sex, age (55–59, 60–64, 65+), household composition and socio-economic position. Households are defined in terms of co-habiting with or without a partner and children. We used the Statistics Sweden coding scheme for socio-economic position which is a categorisation based on information about occupations and education. Occupations were coded in accordance with the Swedish Standard Classification of Occupations 2012 (SSYK12; Statistics Sweden, 2012). These codes were later transformed into ISCO-08 codes (International Labour Office, 2012). Self-reported health was measured on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (very good) to 5 (very poor). We also included a variable that measures the respondent's view of their work situation. This variable is an index based on three questions: (a) how satisfied the respondent is with the job; (b) how well the job matches one's expectations; and (c) how far the current job situation is from a perfect job situation. The index (α = 0.929) is then divided into quintiles.

Also, the answers to the question on preferred retirement age have been categorised into two groups: holding either an early (64 or earlier) or a late (66 or later) preference. Although Sweden has no fixed statutory age of retirement, studies show there is still a widespread opinion in the population that 65 is an appropriate age to retire (Stattin, Reference Stattin2013). We therefore define 66 or later as a late retirement preference.

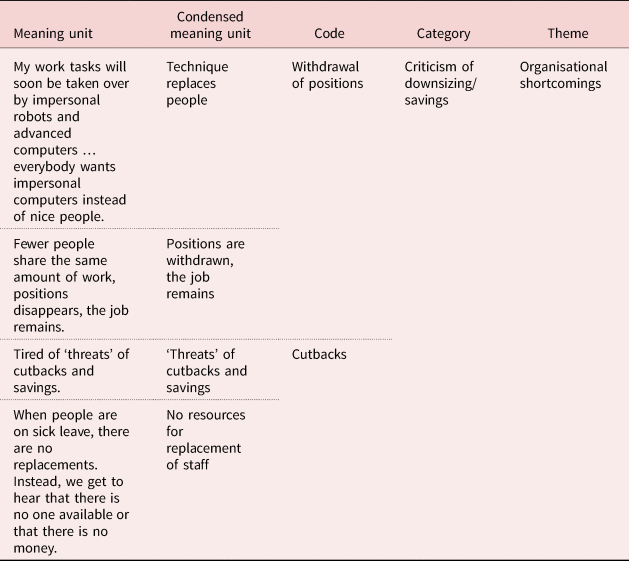

In the second step of the empirical analysis, we used qualitative content analysis (Graneheim and Lundman, Reference Graneheim and Lundman2004; Lundman and Hällgren-Graneheim, Reference Lundman, Hällgren-Graneheim, Granskär and Höglund-Nielsen2012) to analyse how the respondents’ own motives and reasons were related to their preferences. The free-text answers were imported into the qualitative data analysis software, MaxQda 11. Before the preliminary data analysis began, the whole material was read through several times to get a clear overview and a deeper understanding of the data. The material was thereafter scrutinised for words and sentences forming meaning units relevant for the study. With the core message maintained, the meaning units were condensed and assigned preliminary codes. Based on similarities in content, these codes were grouped together into categories that in turn were reviewed in order to look for overarching themes. To improve credibility during the analysis process, the preliminary codes, categories and themes were repeatedly discussed in the research group. During this process categories and themes were gradually modified and revised. Only minor disagreements were found and when differences occurred, the discussion continued until an agreement was reached. An illustration of the analysis process from meaning unit to theme is shown in Table 1. The final analysis is presented in Tables 4 and 5, where each of the two preference groups is described by six themes and their related sub-categories. In the qualitative analysis we refer not to occupational groups, but to each respondent's specific occupation. This has been done with the ambition of reflecting the broad diversity in professions represented in the material. For simplicity, quotes are marked with gender only for men. The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Umeå.

Table 1. Examples of meaning units, condensed meaning units, codes, categories and themes

Results

Retirement preferences

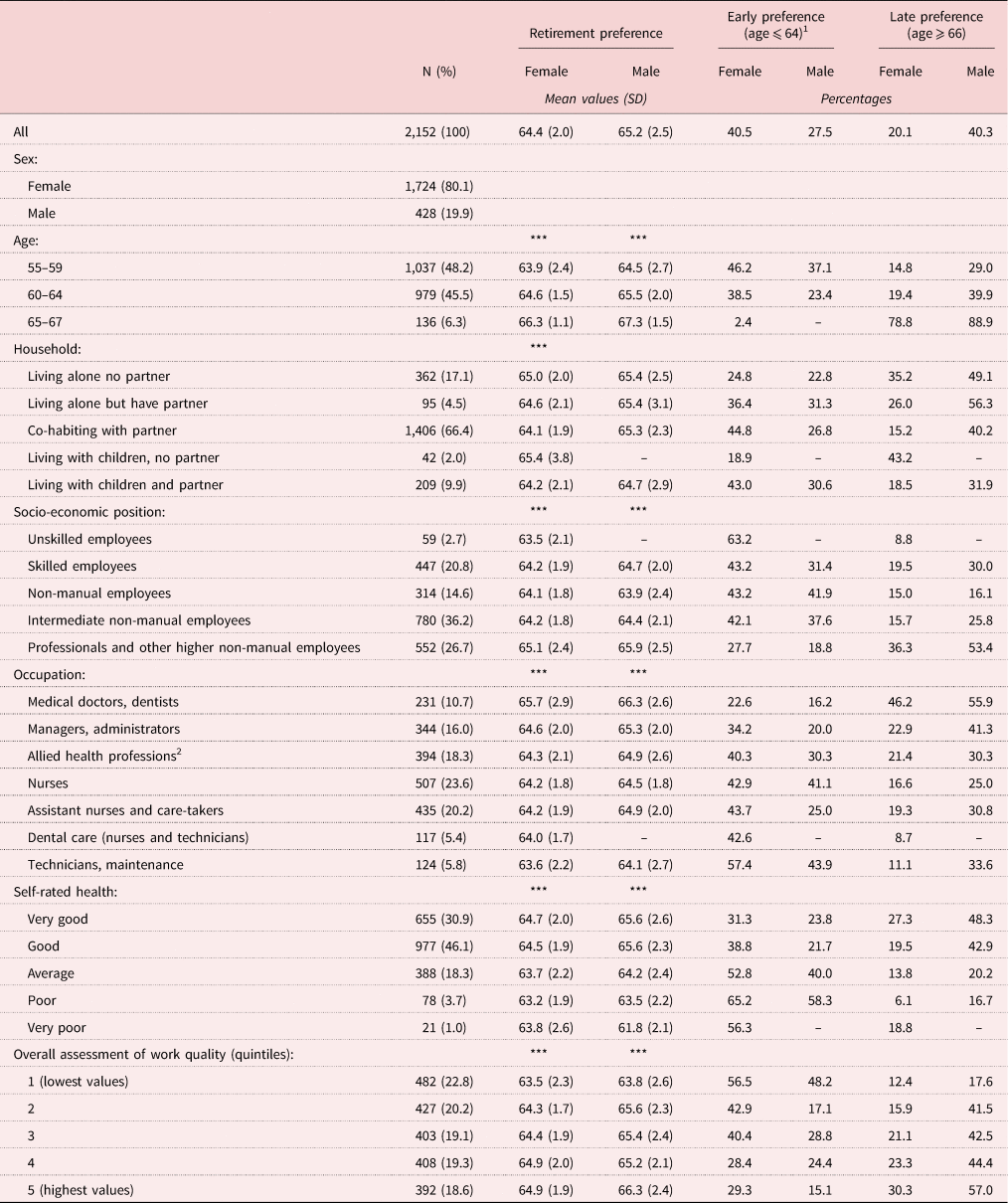

In absolute numbers, the retirement preference varies from 52 to 79 years of age. In Table 2 patterns of retirement preference for different groups of employees are displayed. The table shows quite large group variation in retirement preferences. There is a clear difference in preferences between men and women. Women report on average almost one year lower preference than do men and four out of ten women report a preference lower than 65. The corresponding figure for men is 27 per cent while 40 per cent of the men prefer a late retirement. There is a positive association between age and preferences, and this is true for both women and men. Household composition is significantly associated with preferences only for women, where single women report a higher preference and co-habiting women a lower. However, single women with children tend to report on average higher preferences and also score lowest on relative numbers on early preference (⩽64). This is most likely a result of economic pressure making it hard to leave work early. Socio-economic position is significantly associated with retirement preferences. Respondents with higher hierarchical positions in the organisation report later retirement preferences. We thus see a clear social gradient in preferences. The differences between the groups appears even more clear when looking at the relative numbers that prefer to leave work early. For example, among female employees with the lowest hierarchical position two-thirds want to retire before the age of 65 but only 27 per cent of employees with the highest hierarchical positions. A corresponding pattern is visible also in different occupations. There is a difference of two years when comparing occupational groups with the highest and lowest preference. Medical doctors and dentists score a mean preference over or close to 66 years of age, which is significantly higher than all other groups. Also, male managers and administrators report a preference above 65 years of age while allied health professions report slightly lower preferences. There is limited variation between nurses and assistant nurses, and the lowest preference is noted for technicians and maintenance workers. Worth noting is that women systematically report lower preferences than men irrespective of occupation and hierarchical position. Self-reported health is significantly and positively associated with the preference and the same pattern is visible for employees’ view of their job conditions. Employees with lower levels of job satisfaction report lower preferences and few (<20%) in these groups have ambitions to work after the age of 65.

Table 2. Retirement preferences for different groups

Notes: 1. The 65 year preference is not displayed. 2. Includes physiotherapists, dieticians, clinical psychologists, etc. SD: standard deviation.

Significance level: *** p < 0.001.

Qualitative analyses

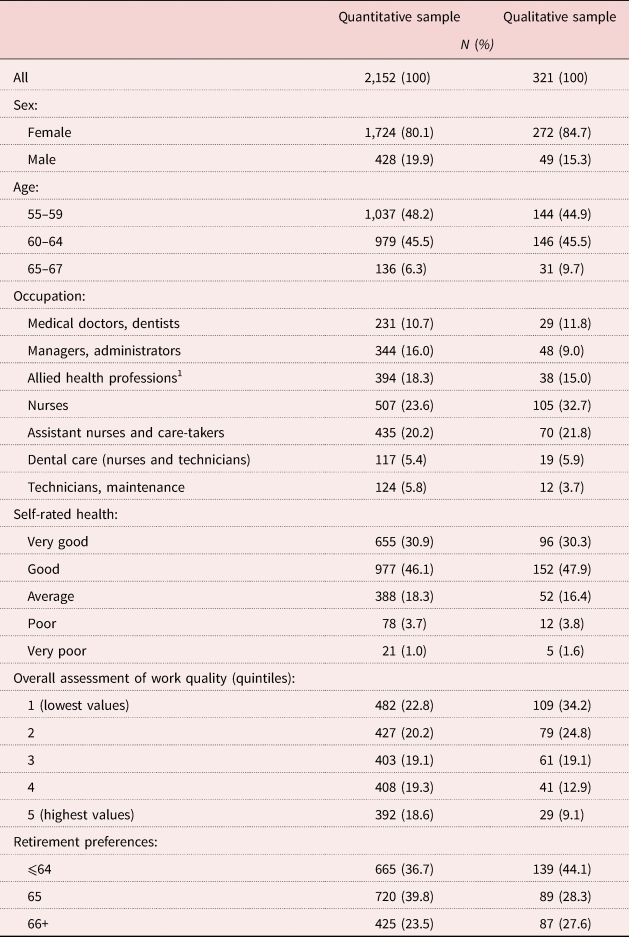

The qualitative sub-sample is a small sample from the survey participants (Table 3). A comparison between the two samples shows that women are over-represented in the qualitative sample as well as employees aged 65 or older. Nurses are also over-represented in the qualitative sample while employees in administrative jobs are under-represented. There are small differences between the samples concerning health, while it is more common to be dissatisfied with one's job in the group with free-text answers. It is also more common in the qualitative sample to report both an early and a late preference. It is thus clear that the qualitative sample does not entirely reflect the total group of survey participants, especially concerning how they view their work situation. Although the sub-sample is not entirely representative, it includes respondents with all kind of preferences, which is important for finding motives for both early and late preferences.

Table 3. The quantitative and qualitative samples

Note: 1. Includes physiotherapists, dieticians, clinical psychologists, etc.

Respondents’ motives for early retirement preferences

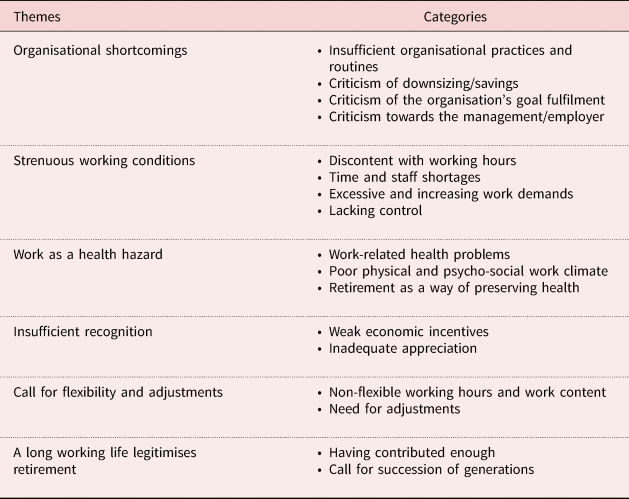

When describing their motives for wanting to retire at 65 or earlier, the respondents expressed critical views of the organisation and their working conditions, often with strong expressions and discontent. Their views can be summarised through the following six themes: (a) organisational shortcomings, (b) strenuous working conditions, (c) work as a health hazard, (d) insufficient recognition, (e) call for flexibility and adjustments, and (f) a long working life legitimises retirement (for an overview of the themes and related categories, see Table 4). The first two, ‘organisational shortcomings’ and ‘strenuous working conditions’, are the most extensive and central themes for holding an early retirement preference.

Table 4. Summary of themes and categories related to early retirement preference

Organisational shortcomings

The first theme comprises categories that all refer to shortcomings and criticism of the organisation. The critique is mainly directed towards organisational practices, downsizing, the organisations lacking the ability to uphold the core objective of providing high-quality health care as well as criticisms of the management. The theme illustrates how disapproval towards the organisation itself and the workers’ experience of their employer's organisational failures work as explicit motives for wanting to retire early.

Criticism, for example, is directed towards various organisational practices such as ‘constant reorganisations’ where the organisation, for example, is described as ‘a complete mess’ that over time wears its workers out by not providing a stable structure; or as one dental assistant bluntly puts it: ‘reorganisations that kill!’ Lack of goals, planning and foresight, together with poor HR policies, are furthermore addressed. Like critical views of downsizing, they highlight and demonstrate the participants’ dislike of the organisation's eagerness to save money by ‘cutting corners’. The employees describe their feelings of being ‘fed up’ with the economic savings that, for example, have come to reduce the numbers of both employees and hospital beds, causing shutdowns or merging of wards and limiting the possibility of getting replacements for sick leave, as described by one of the cleaners:

When people are on sick leave there is no one to fill in for the absence. Instead, we get the answer that there is no one available or that there is no money for it. We do the work of several [people]!

Closely related to downsizing is the criticism of the organisation's goal fulfilment. Here, the respondents express their frustration with the focus being shifted from high-quality health care to administration and ‘effectiveness’, which is illustrated by the following statement from one of the care-takers:

Until a few years ago, the work consisted of high-quality treatment with good results. Today, it is not as meaningful anymore. Today it is all about administration, counting the numbers of visitors … shallow contact with patients. Quantity is more important than quality!

Disapprovals of the organisation's decreased focus on health-care quality is also described through the employees own feelings of insufficiency: ‘Too few workers and a heavy work load. The feeling of knowing that you won't be able to help the patients the way you want to’ (assistant nurse). Other respondents also raise their concerns of overcrowding and questionable patient safety.

The management of the organisation is another target of criticism, frustrations over absent and unclear leadership are described frequently, as is exemplified by the following quote from a nurse: ‘the head of department has such a large area to be responsible for that we are left with a management without vision, initiative, development, etc.’ Problems with specific managers and incompetent management in general are also addressed within this category, as is illustrated by this medical doctor pinpointing three causes for her early retirement preference: ‘The senior management, no way to have influence, my closest boss.’ Commonly, the respondents line up a combination of several critical statements, such as: ‘Constant reorganisations, no foresight, decisions are not followed up. It is all about saving money!’ (assistant nurse). Others recognise that the effects of the organisational let-downs are not limited to one's own individual preference to leave early but express a tendency for organisational withdrawal on a more a general level. One assistant nurse asks, for example: ‘How shall we be able to work until 65 with this work pace? All the cutbacks in hospital beds and staff fleeing the health-care sector.’ Another assistant nurse points out that a ‘“messy” organisation and lack of clarity makes the staff turnover catastrophically high’. Less-specified criticism towards the employer is also voiced, as illustrated by this nurse who states: ‘I am not proud to be working for this organisation.’ Others express feelings of being ‘sick and tired’ of the organisation or that they think they have a ‘bad employer’.

Strenuous working conditions

The categories in the second theme are highly related to each other, generating an account of strenuous working conditions that separately and/or together push the workers towards a preference for early retirement. The respondents stress that discontent with working hours as well as difficulties with recovery due to inconvenient hours work as motives for wanting to retire early. A man working as an assistant nurse explains: ‘Nobody manages to work until 65 in my job: 44 hours per week attendance time, 16 different shift schedules, heavy workload due to bad prerequisites equals under-staffing, on duty every second weekend, no time to eat due to workload, three different vacation periods.’ One of the midwives also brings forward the relation between recovery and shift work: ‘The working hours, with three shifts, and the night shifts in particular are strenuous. It takes a longer time to recover.’ The discontent with working hours makes one of the assistant nurses conclude: ‘I want to be free from work on evenings and weekends.’ Further lies a tale of time and staff shortages in combination with excessive demands, where there is ‘Not enough staff in relation to workload’ (nurse). One of the counsellors elaborates:

I have interesting working tasks – but I do not have the time to perform them. It often becomes stressful, high psychological pressure. I hate to end the working day with high levels of stress, knowing there is not enough time to be able to carry out the tasks. I have a feeling that I am ‘chasing’ minutes in order to be as effective as possible.

Furthermore, one of the assistant nurses concludes: ‘My work has come to involve so much pressure, stress and heavy workload that I will be happy if I manage to work until the age of 63.’ All in all, many think that the work situation has become ‘worse than before’.

For some respondents, new and challenging work tasks as well as technical equipment become difficulties to cope with, as is indicated by this midwife who described a heavier workload due to ‘new changes all the time especially in terms of technique and computer work’. One dental assistant further confesses: ‘I can't stand all the new techniques and challenges.’ Thus, new technological development is a concern for some employees.

The experience of lacking control over one's own work situation is evident throughout this theme. One of the dental nurses explains that there are ‘no means to have influence over the working situation’. Others describe lack of influence over both working content and working hours, the sense of being unable to affect the balance between resources and demands, and the experience of not being listened to when trying to make one's voice heard.

Work as a health hazard

Given the strenuous working conditions mentioned above, work is often regarded as a health hazard. The categories in the third theme all illustrate how the employees are experiencing health problems due to their work, both physically and mentally. One of the assistant nurses says: ‘My body is completely worn out after 45 years in this organisation.’ Others mention stress and even more severe conditions such as fatigue syndrome. Some employees also express how an early retirement is viewed as a way of preserving health and to prevent or delay (further) illness: ‘For my body to last also after retirement. It matters what kind of work you have had!’ (nurse). One unit manager further illustrated how work negatively impacts on her health: ‘Heavy workload and a health condition that doesn't withstand that heavy workload/stress. Risk of “dying at one's post”’. Not quite as prominent, nonetheless important to the employees’ experience of work as a health hazard, are the concerns about poor physical and/or psycho-social working climates.

Insufficient recognition

The fourth theme, insufficient recognition, is built up by categories illustrating the respondents’ experience of not being valued by their employer. Some stresses that low wages and a lack of economic incentives impact their willingness to remain in paid work, e.g. one nurse states: ‘If it would pay off economically to work longer, I would consider doing it.’ A more salient experience relates to feelings of not being appreciated in a broader sense, where, for example, not experiencing any gratitude for the work carried out and/or feelings of being easily replaced are pervasive. Another dimension of insufficient recognition concerns the impression that skills and experience are not being utilised nor requested by the employer. In some cases, this gets associated with older workers in particular: ‘I feel like the most important thing to my employer is to recruit young, recently graduated people. The employer is not interested in older workers with much experience. They do not want us’ (care-taker). One of the assistant nurses makes a similar comment: ‘No one makes use of long working experience and long life experience. Amongst other things, this is evident in the salary within this organisation.’ Others, like this assistant nurse, relate the lack of recognition more explicitly to her occupational category and the insufficient opportunities for training and development: ‘The fact that my employer doesn't do anything to stimulate or develop the competencies of assistant nurses makes it a relief to quit working and stop feeling that my entire profession is being questioned.’

Call for flexibility and adjustments

The fifth theme assembles categories that in different ways address the employees’ call for flexibility and adjustments in order to prolong working life. Lack of flexibility both in terms of working hours and work content is clearly stressed, as well as the fact that increasing possibilities for adjustments would have made it doable and appealing to work longer, as shown in the following quote by one of the nurses: ‘It is too demanding in the long run to work day, night, weekend. I would be able to work longer if there was the possibility of daytime work and reduced hours’; or as this head of department explains: ‘I could have been able to work … about 50 per cent, with suitable work tasks. It didn't even have to be directly related to my domain of work.’ One of the nurses proposes a customised type of position: ‘It should be possible to get some sort of senior-employment where I could take time to be a “mentor” – get some limited working tasks’. In some cases they also identify various organisational obstacles impacting on the possibilities for more flexible solutions: ‘[Its] hard to get permission to decrease one's working hours due to lack of nurses and unwillingness from the managers’ (nurse).

A long working life legitimises retirement

In the compilation of categories that communicate a long and faithful service as well as the wish to ‘pass the baton’ to younger colleagues, the sixth and final theme reveals the employees’ recognition of having ‘done their part’ and that their working lives are completed. Often reported in numbers of years, many respondents stress their commitment and dutifulness during their working lives and conclude that retirement is right, as articulated by this woman working as a nurse: ‘I have been working since I was 14 years old. Have been working for nearly 50 years … so I have earned a calmer life after 65’. Several also advocated that old workers should be replaced with young ones. One care-taker expressed this as a wish to: ‘Hand over my job to a younger person, hence give that person the opportunity of getting a permanent position.’ Such statements are based on ideas that the young and strong should take over the burden of work, or that older workers can and should ‘step down’ in order to make room for the young and give them access to employment and by that express solidarity with younger generations.

Motives for a late retirement preference

The motives for wanting to prolong working life beyond the age of 65 by and large consist of personal experiences of work being a great and highly important part of one's life. Commonly for those with a late preference are their predominantly positive descriptions of work, where they feel able and motivated to continue working and feel appreciation and recognition for the work they do. The statements are summarised in six themes, as shown in Table 5. The first five focus primarily on positive aspects such as: (a) work promotes physical and mental wellbeing, (b) work gives meaning and satisfaction, (c) competencies and knowledge are utilised, (d) feeling able and motivated, and (e) flexible solutions are at hand. The last theme, (f) financially dependent on work, illustrates, on the other hand, how financial needs make them keep on working.

Table 5. Summary of the analysis in themes and categories related to a late retirement preference

Work promotes physical and mental wellbeing

The first theme consists of coinciding categories that all point out how work in different ways is important to the respondents’ physical and mental wellbeing. The significance of work in terms of wellbeing is being emphasised by descriptions of the importance of social contacts and relations to colleagues, something they think they would miss if they did not have them. In this sense, work helps to prevent loneliness and passivity. One of the assistant nurses expresses her fears of how a life without work would be: ‘I don't want to be stuck at home in an apartment without friends and with nothing to do.’ Work is also believed to promote both structure and routines in life. One of the medical secretaries explains that her job provides ‘social contact with colleagues [and] routines for everyday life’. Others emphasise the ability of work to promote good health in general, which includes statements such as: ‘work is good for your health’ or as this man working as a care-taker puts it: ‘[work makes you] keep up the mental and physical vitality’.

Work gives meaning and satisfaction

The second theme gathers various positive accounts of work. In different ways, the statements within this theme highlight feelings of enjoyment and satisfaction, as well as expressions of how work itself contributes to feelings of appreciation and recognition. Several respondents describe their work as interesting and enjoyable with work tasks they find stimulating and rewarding. The daily contact with patients is brought up as a particularly important issue. One of the assistant nurses illustrates this view when stating: ‘I love my work because of the patients. It's they who think that I am doing a good job, praise me and greet me with a smile on their lips when I arrive at work in the evening and think it's fun that I am coming.’ The recognition and gratitude they receive from patients as well as co-workers and in some cases also management contribute to a sense of satisfaction with the work carried out: ‘My work is appreciated. I feel needed. My competencies and my experience are important and is appreciated by patients and colleagues’ (nurse). But some also express a lack of recognition from the management or employer, which impacts on their view of continued work. One respondent explained that even though she wants to work beyond the age of 65, she is not sure if she want to stay with her current employer: ‘I like my job, but I don't want to work in an organisation that doesn't value my knowledge.’ Recognition and appreciation are thus viewed as important aspects for a prolonged working life; and, moreover, are linked to the next theme of utilising competencies and knowledge.

Competencies and knowledge are utilised

The third theme raises the respondents’ awareness of and desire to utilise their competencies that they think ‘contribute with knowledge and expertise to the organisation’. Besides this, they view knowledge transfer as a very important task and express a wish to transfer their competencies to younger colleagues, as is explained by this man working in a management position: ‘I like to share my many years of professional experience with the younger co-workers. That means a lot.’ The ability to make use of competency investments and making them ‘worthwhile’ is also highlighted by this medical doctor who states: ‘I have a long, expensive [to the state] training that should be utilised for as long as possible’, or as this nurse, who graduated later in life, puts it: ‘I have not gone through education just to retire, but want to continue to work until I get bored of it or my body needs a rest. And that might take some time.’

As for feelings of commitment and loyalty, several employees mention having unfinished undertakings, as explained by this nurse: ‘I would like to follow through the projects that I have been responsible for and been working with for the last ten years.’ Others were aware of staff shortages and lack of special competencies in their profession and wanted to help out by staying on. One pedagogue from a specialised field concluded: ‘It is hard to recruit to my profession’ and one of the medical doctors noted: ‘I will be needed because of a shortage of doctors.’ Thus, this willingness to continue working in later life can be understood in terms of organisational commitment and loyalty.

Feeling able and motivated

In this theme, the employees base their late retirement preference with feelings of being healthy, able and willing to work. A common view is that a prolonged working life is possible as long as one is healthy, as one of the nurses explains: ‘I am healthy … As long as I am healthy I see no hindrances to continue working.’ Others, like this medical doctor, describe how they feel motivated and continuously want to ‘develop and learn new methods’. They describe driving forces such as ‘curiosity, interest learning more, not finished yet!’ Some also state that they have not thought of retirement and instead express feelings of being ‘too young’ for retirement: ‘Currently, I feel too young to even be thinking of retirement’ (nurse). This dietician clarifies that her decisions on when to retire are not yet taken: ‘I haven't even considered the age for retirement, I will definitely keep on working until 65 and after that I can evaluate how life is then.’ As such, retirement is described as a matter still placed in the future, something to which they have not yet paid much attention.

Flexible solutions are at hand

In the fifth theme, the respondents describe how possibilities to impact on their work situation contribute to the willingness to prolong their working life. Employees who have been provided with the opportunity to influence and decide on their work tasks, hours and retirement processes express feelings of being ‘free’ and in control of their own work situation. One medical doctor declared: ‘I decided to work part-time [25–50%] after 65 years of age, on my own conditions, i.e. when it suits me. Because my patients and my employer need me.’ Some employees also describe how they completely or partly have chosen to change or alter their direction of work. New, adjusted and more autonomous working tasks are thus described as motives for continued work. One of the nurses concludes: ‘I will have other tasks … it is exciting, freer, I will have more influence over my work.’ Possibilities to influence the work hours are also described as positively affecting future retirement plans. Several also describe positive aspects of a phasing-out period and how a slow decrease in hours is preferred over retiring abruptly, as described by this nurse: ‘I think it would be good to gradually cut back. Not go from 100 to 0.’ Another nurse also raises negative effects of abrupt cuts:

I can imagine working part-time after 65 because actually I enjoy my work besides I think it might be good to not stop working abruptly but rather gradually cut back. I have seen many people become depressed when they retire.

Working part-time is thus seen as an attractive solution and some employees, such as this physiotherapist, illustrate concrete plans on how they reason about their future service grade: ‘[I'm] hoping to work 50–75 per cent after turning 60 and instead prolong [working life] by two years’. For others, like this medical doctor, flexibility and possibilities to work part-time are described as an absolute must in order for them to manage and to be willing to continue working:

I have reduced my working hours in order to cope and to not get burned out. If my employer demands full-time work and for me to be on call [as I am now] I will quit instantly!

Financially dependent of work

Although being one of the less-prominent themes, being financially dependent of work is still the harsh reality for some. Several workers state that due to their economic situation they feel forced to continue working although they would have preferred to stop or consider a phase-out. Some, such as this specialised nurse, refer to their family situation: ‘Since I live alone, the income is my first priority, but I wish I could afford to work part-time from the age of 60.’ Others like this male dentist bluntly state: ‘I just can't afford to retire, it is as simple as that!’ In other cases, an extended working life is necessary even though one's health falters: ‘I just cannot afford to retire, despite illnesses. I just hope I can cope until the economy looks better’ (medical secretary). Fear of a low pension is also mentioned as an imperative force for continued work.

Discussion and conclusions

The focus of this study has been to explore retirement preferences and work-related preference motives among older employees in a large health-care organisation in Sweden.

The study departed from a quantitative analysis of the distribution of preferences in the organisation. The results show first of all substantial differences in retirement preferences. One interesting result is that single women with children are noted for comparatively late preferences which we interpret as a stuck mechanism. It is simply not possible for this group to end work because of economic pressures which in turn results in adaption towards later preferences. We also saw that a strong social gradient is revealed in the employees’ views of timing of retirement, where a dominance of early preferences is seen in low and middle classes in contrast to a much larger prevalence of late preferences in higher occupational classes. A clear gender pattern is visible, where women systematically report lower preferences than men. To some extent this can be explained by the strong gender segregation in health-care organisations. But women also report lower preferences in the same social class or occupation, indicating that other factors may explain these differences. In part, such differences might, for example, be a reflection of the tendency for partners to retire simultaneously, where women often are younger than their partner. The quantitative data also show that the respondents’ views of their working conditions are important for the preferences and this finding was further elaborated on in the qualitative analysis.

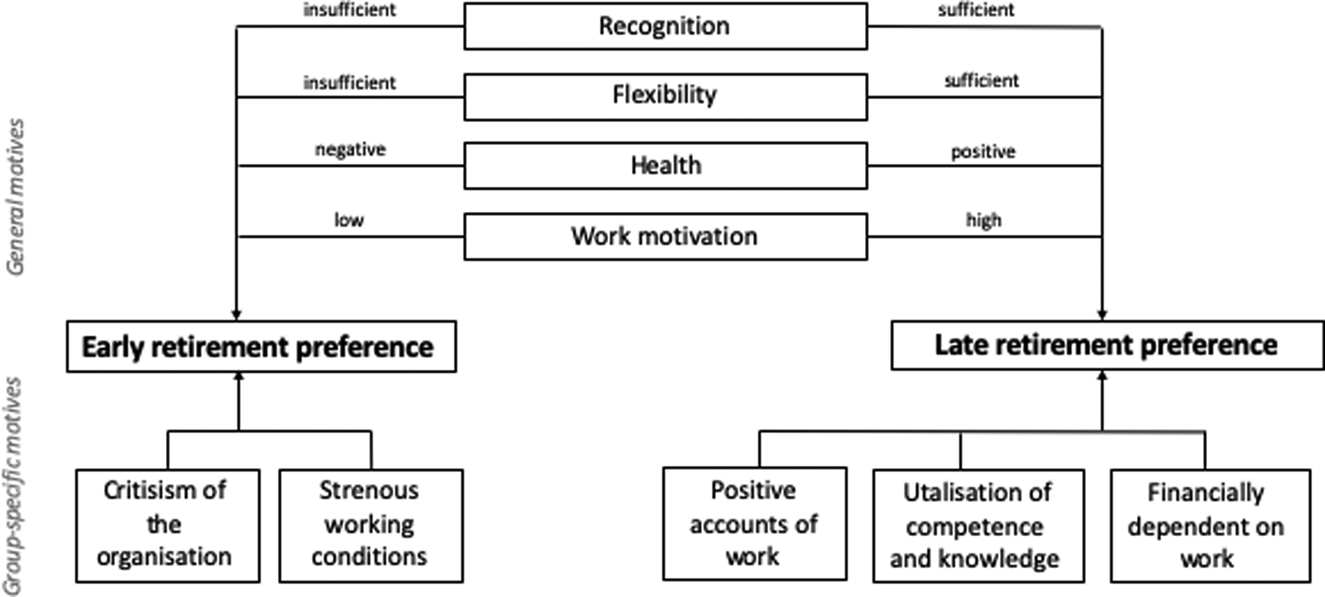

In Figure 1, we summarise the results from the qualitative analysis in two overarching types of motives: general and group-specific.

Figure 1. A summary of the free-text motives for early and late retirement preference.

The general motives are shared by both the early and late preference groups and include recognition, flexibility, health and work motivation. The group-specific motives are exclusively related to either an early or a late retirement preference. Criticism towards the organisation and strenuous working conditions are specific motives for an early retirement preference, while positive accounts of work and a wish to utilise one's own competencies as well as being financially dependent on work are stated as specific motives for wanting to retire late.

The general motives comprise factors that run along a continuum from insufficient to sufficient or from low to high, and the retirement preference depends on where on the continuum the employee is positioned. One and the same factor can thus be considered as both a push factor and a stay factor. In relation to contemporary ambitions to prolong working lives, all four general motives appear to be important to consider. First, recognition and feelings of being appreciated by the employer, co-workers and/or patients were viewed as an important motive for continued work. This finding is supported by earlier studies that report a link between appreciation and retirement, arguing that employees tend to retire at an early age when they are and/or feel unappreciated, while those that experience appreciation often prefer to stay longer (e.g. Hilsen and Midstundstad, Reference Hilsen, Midstundstad, Hasselhorn and Apt2015). Organisational support, e.g. the way an employer communicates the value it places on its older workers, is thus of importance for continuous work participation among older workers (Armstrong-Stassen and Ursel, Reference Armstrong-Stassen and Ursel2009; Appannah and Biggs, Reference Appannah and Biggs2015). Likewise, earlier research found supportive work practices (such as recognition of skills and abilities, training opportunities and possibilities to pass on knowledge) important when retaining older-age care workers (Mountford, Reference Mountford2013).

Second, flexibility, e.g. the possibility of adjusting working hours, schedules and work assignments, is furthermore highlighted and related to feelings of having or lacking control. Respondents with late preferences quite strongly referred to job control and real possibilities of adjusting work conditions as not only important but crucial factors for their choice of preference. Findings reported elsewhere have also recognised flexibility to be an important work factor in order to prolong older workers’ careers (e.g. Appannah and Biggs, Reference Appannah and Biggs2015; Perera et al., Reference Perera, Sardeshmukh and Kulik2015; Nilsson, Reference Nilsson2017).

Third, as in many other studies, health is frequently identified as a central aspect influencing the possibilities for future work (see e.g. Gyllensten et al., Reference Gyllensten, Wentz, Håkansson, Hagberg and Nilsson2019). While work was seen as a health hazard among some, others saw it as a way to preserve or even promote health. Similar to earlier studies, continuous work was in some cases even regarded as a health investment in order to avoid different (severe) health problems (see e.g. Nilsson, Reference Nilsson2017: 25). These results further enhance the importance of health and wellbeing at work, as well as the importance of providing an organisational culture that promotes good physical and psycho-social health in order to prolong workers’ careers (Appannah and Biggs, Reference Appannah and Biggs2015).

Fourth, work motivation, the last general motive, further illustrates the sharp differences in how continued work and retirement were viewed.

Some respondents with an early preference described how their long working lives have impacted on their motivation to carry on working. They felt that their working lives were completed, that retirement at 65 or earlier was rightfully earned and that older workers should step aside to make room for younger generations. Similar views have also been found in other empirical studies of, for example, health-care employees (Nilsson, Reference Nilsson2017), and can be related to earlier statuary/traditional retirement age and to historical interventions of trying to solve unemployment by encouraging older workers to retire early (Kohli et al., Reference Kohli, Rein, Guillemard and van Gunsteren1991; Reday-Mulvey, Reference Reday-Mulvey2005). Others, with a late preference, felt highly motivated and expressed a strong drive to continue their working life. Retirement was ‘uncalled for’ at this point as they felt healthy, able and simply too young to step down. Thus, they felt they had more to give and that they were still valuable to the organisation. Identifying such motivated individuals give employers increased possibilities to retain older workers. Recent research has also identified new/changing patterns of work and retirement among older employees who, for example, may continue their career job, or become involved in phased retirement or in bridge employment (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Choi and Goode2013; Beehr and Bennet, Reference Beehr and Bennett2015; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Dorey, Chaffee and Sonnega2016).

The results display striking differences between the early and late preference groups concerning group-specific motives. While the early preference group is strongly critical of the organisation and the demanding work situation, the group with late preferences report very positive accounts of their work and strive for continuous utilisation of their own competencies and knowledge. The respondents express quite strongly that two important dimensions of the psycho-social work environment (Karasek and Theorell, Reference Karasek and Theorell1990), demands and control, are central in their articulation of reasons for holding a specific preference. Real possibilities to adjust or change the work conditions are even seen as a basic prerequisite for striving to work for a long time. Those with early preferences, on the other hand, strongly point at the limited options available to affect the work situation given their individual needs. The control dimension appears to be closely linked to the employer's willingness to offer flexible solutions based on individual needs. This result is consistent with, for example, Ng and Feldman (Reference Ng and Feldman2014) who state that improved autonomy (control) has positive effects for all employees, not only for older workers. Various organisational issues are also brought up in studies of elderly care workers (Gyllensten et al., Reference Gyllensten, Wentz, Håkansson, Hagberg and Nilsson2019). Having the possibility to transfer knowledge and expertise has also been identified as important for many older workers in earlier studies (Nilsson, Reference Nilsson2017). Moreover, Armstrong-Stassen and Ursel (Reference Armstrong-Stassen and Ursel2009) conclude that key practices related to retention of older employees is to ensure that they have interesting and challenging work assignments and that they are provided with opportunities to upgrade and acquire new skills.

With reference to organisational shortcomings and continuous work intensification, the early preference group is clearly discouraged from working longer. Also, the fear of deteriorating health due to the nature of their work situation implies limited control and choice concerning the decision to continue to work. The general impression from the qualitative accounts is therefore that those holding a wish to retire early are disadvantaged when it comes to their possibilities of work in late age compared to employees with late retirement preferences. As suggested by Lain et al. (Reference Lain, Airey, Loretto and Vickerstaff2019), those in such a disadvantaged position may feel a sense of insecurity and precarity given contemporary retrenchments in public policy support and low pension incomes for early retirees. The fact that some respondents found themselves financially dependent on continuous work and felt compelled to work longer even though they might not wish to can be interpreted in a similar manner. This adds to the impression that these employees experience a low level of control over the retirement decision process, which stands in stark contrast to the present debate on extended working lives as a matter of an individual's choice (Lain et al., Reference Lain, Airey, Loretto and Vickerstaff2019).

From a general welfare perspective, this is an important message that implies that the strong public discourse of extended working lives needs to be problematised to a greater extent than it has been so far. Ambitions to extend working lives for more than already-privileged groups of employees, those in good health and with favourable working conditions, require retirement policies and interventions that are sensitive to the heterogeneity and the different prerequisites amongst older workers to avoid increased inequality gaps. However, eligibility to public financial support for employees with limitations in their work capacity have been drastically tightened in Sweden during the past decade (Söderberg et al., Reference Söderberg, Mannelqvist, Järvholm, Schiöler and Stattin2018), which means that there are very few public support alternatives available for older workers who are unable to work in late age. Instead, there is an increase in the relative number of people taking old-age pensions at pre-retirement age, which in turn is a tendency of a re-commodification of older workers (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990). This implies an individualisation of risk concerning older people's welfare since taking old-age pensions at an early age has negative effects on pension incomes for the rest of a pension recipient's life. The patterns of retirement preferences as described in this study point towards a discrepancy between the public policy ambitions of extended working lives and the reality of many employees’ retirement prospects. Given this discrepancy, public policy measures need to recognise the far-reaching variability in preconditions for work in late age, as well as the need for adjustments in work conditions in order to realise a prolonged working life for more than privileged employees.

Practical implications

One central message from this study is that the results strongly indicate the negative impact of organisational and working conditions on retirement preference. This finding demonstrates a need for and a potential to influence retirement preferences by improving organisational practices and routines as well as working conditions for older workers which further enhance the need for adequate HR strategies targeted at retaining older workers (see e.g. Hasselhorn and Apt, Reference Hasselhorn and Apt2015; Hilsen and Midstundstad, Reference Hilsen, Midstundstad, Hasselhorn and Apt2015; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Dorey, Chaffee and Sonnega2016).

Our results draw attention to the heterogeneity amongst older workers’ prerequisites for a long working life and thus the core problematic with general, collective HR interventions (that have been dominating the Swedish context) targeting such a diverse group. This suggests that when designing HR interventions to retain older workers, employers may need to consider the working conditions specific for certain professions in order to implement adequate and tailored interventions and adjustments that address real problems. In addition to profession-specific interventions, the matching of interventions to the workers’ individual requests and needs are also emphasised in the literature through the need for I-deals (Hornung et al., Reference Hornung, Rousseau and Glaser2008; Bal et al., Reference Bal, De Jong, Jansen and Bakker2012). For the employer, this means that adequate interventions may need to be developed in close negotiation with the older worker.

An early and active dialogue with the individual worker also allows the employer to gain understanding about the individual employee's health status, what adjustments and/or flexible solutions she or he would find valuable, and what push and stay factors to adjust in order to motivate and enable a postponing of retirement. To increase the chances of a successful retention of a satisfied and motivated older employee, and to avoid unnecessary expenses, such understanding may be of great value to the employer in developing HR interventions. In order to provide more concrete and applicable guidelines, a broadened and deepened insight in organisational contexts (including work environment, prevailing attitudes and norms towards older people and an ageing workforce among both employers and co-workers) as well as the conditions for specific occupations and individual reasoning (including both work- and non-work-related issues) is needed.

Weaknesses and strengths

This study's main empirical base has been a sub-sample of qualitative free-text answers reported in an large organisational questionnaire. In comparison with the total sample, the sub-sample included participants that were more dissatisfied and had lower retirement preferences than participants in the total sample. This means that they display more critical attitudes towards the organisation and the work conditions than employees on average. We argue that this does not necessarily need to be a negative aspect since the qualitative data have provided us with a large number of detailed accounts and descriptions of work-related factors that are of great relevance to the formation of retirement preferences.

The study contributes to the field by mapping not only what work-related conditions serve as motivators to prolong older workers' careers (stay factors), but also the factors fostering early retirement preferences (push factors). The open answers and thereby the possibility to capture the respondent's own reasons for a specific retirement preference deliver an opportunity to add to existing known workplace factors and to provide a more nuanced picture. The results also reflect patterns of preferences from a very broad spectrum of occupations, although in one single sector, which does not allow us to draw general conclusions relative to the population overall.

However, the results are to a large extent supported by previous studies, which provide robustness to the results and improve its transferability to other groups of health-care workers with similar working conditions (Gyllensten et al., Reference Gyllensten, Wentz, Håkansson, Hagberg and Nilsson2019). This study has had an explicit focus on work-related motives in order to reach a deeper understanding of employees’ perceptions of workplace influence on retirement preferences. It should be mentioned though that circumstances outside work most often are closely interlinked with work experiences in shaping both retirement preferences and the actual timing of retirement (Gyllensten et al., Reference Gyllensten, Wentz, Håkansson, Hagberg and Nilsson2019).

Further research needs

Our results provide evidence of substantial differences between occupations and social classes. As older workers are a heterogeneous group, it includes a great variety in working conditions and prerequisites to work in old age. Therefore, when seeking to develop advantageous and non-discriminatory policies for prolonging working lives, a deeper understanding of the inequality and diversity amongst older workers both on occupational and individual levels is a crucial research question for the future. On an individual level, a deeper understanding of the possibilities for I-deals is necessary. It is further important to highlight the potential risk that perceptions of organisational injustice may arise in relation to the idea of more-differentiated and individualised HR measures. Another important aspect not specifically targeted here is gender. Future research calls for analysis of both similarities and differences between both women and men, and between and within specific occupations (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Dorey, Chaffee and Sonnega2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the studied organisation and all the staff who participated in the study. We would also express our gratitude to Stina Hallström ) for her contribution to the initial analysis.

Author contributions

MS was responsible for the conception and design of the study. Both authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, and the drafting and revising of the article.

Financial support

The research is part of the project "Keys to a longer work career. Individual and organizational perspectives", Dnr 2014-04557 and the project “Paths to Healthy and Active Ageing”, Dnr: 2013–2056 both funded by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Umeå (Dnr 2014/243-31Ö).