Introduction

The concept of ‘home’ is complex and recent years have seen a proliferation of literature on the meaning of home within the disciplines of sociology, anthropology, psychology, human geography and gerontology (Peace, Reference Peace, Twigg and Martin2015). Home is not simply a physical space. It also denotes a meaningful ‘place’ which embodies physical, personal and social dimensions (Wahl and Oswald, Reference Wahl, Oswald, Dannefer and Phillipson2010) extending beyond the household itself to encompass the neighbourhood and wider community (Bigonnesse et al., Reference Bigonnesse, Beaulieu and Garon2014). According to Mallett (Reference Mallett2004: 83), the term home ‘functions as a repository for complex, inter-related and at times contradictory socio-cultural ideas about people's relationship with one another, especially family, and with places, spaces, and things’. Home can be a dwelling place or a lived space of interaction between people, places and things; or both. While the concept of home is mostly seen as positive and supportive, Peace (Reference Peace, Twigg and Martin2015) recognised that home, particularly in later life, can also be a place of abuse and social exclusion; where loneliness, frustration and conflict are found.

According to Visser (Reference Visser2018), while much literature has focused on the meaning of home, relatively little has been conducted on home-making in later life. Visser argues that home is a process rather than a static entity, and that people's conceptualisation and experience of home develops throughout their lives. This view is consistent with the work of Baxter and Brickell (Reference Baxter and Brickell2014), who argued that home can be ‘made and unmade’ through home-making practices. What these practices entail, and how they change and develop over a lifetime, is strongly influenced by the cultural context in which they take place (Visser, Reference Visser2018). In this way, feeling at ‘home’ can be recreated in other locations such as hotels (Duyvendak, Reference Duyvendak2011) and nursing homes (Cooney, Reference Cooney2012; Lovatt, Reference Lovatt2018). In Ways of Home Making in Care for Later Life, Pasveer et al. (Reference Pasveer, Synnes, Moser, Pasveer, Synnes and Moser2020) explored how home is made when care enters the lives of people as they grow old at home or in ‘homely’ institutions. In shining a light on this phenomenon, Pasveer et al. consider home a verb; something people do, and, in this way, home is always in the making, temporal and open to negotiation. They further highlight the importance of people's tinkering and experiments with making home, and conclude that it is in the course of these activities that home is being made and unmade (Pasveer et al., Reference Pasveer, Synnes, Moser, Pasveer, Synnes and Moser2020).

Bridges (Reference Bridges2004) articulated the significance of transitions in an individual's life and suggested that whilst transitions can be considered normal phases linked to the various lifestages, special consideration should be given to the many transitions associated with the ageing process and the care of older people. This is supported by others who recognised that the transition to life in a care home is a major life event for older people and their families (Cooney Reference Cooney2012; O'Neill et al., Reference O'Neill, Ryan, Tracey and Laird2020). The distress and anxiety associated with this move has been repeatedly highlighted in the literature (Penney and Ryan, Reference Penney and Ryan2018; O'Neill et al., Reference O'Neill, Ryan, Tracey and Laird2020). The extent to which older people are treated with dignity and respect and can exert voice, choice and control before, during and after the move is key in supporting them to adapt and ‘feel at home’ in their new surroundings (Cooney, Reference Cooney2012; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Simpson and Froggart2013; O'Neill et al., Reference O'Neill, Ryan, Tracey and Lairda, Reference O'Neill, Ryan, Tracey and Lairdb).

In their systematic review of 19 studies on the factors that impacted residents’ transition to long-term care, Brownie et al. (Reference Brownie, Horstmanshof and Garbutt2014) concluded that a positive adjustment was influenced by the extent to which older people were able to retain personal possessions, continue existing relationships and establish new relationships within the care facility. Ryan and McKenna (Reference Ryan and McKenna2015) highlighted the significance of ‘the little things’, and the importance of respecting lifetime rituals and routines in the creation of a homely environment.

Cooney (Reference Cooney2012) identified four categories as significant to ‘finding home’ in long-term care settings. These were: ‘continuity’, ‘preserving personal identity’, ‘belonging’ and ‘being active and working’. Older people's ability to ‘find home’ was influenced by individual factors (adaptive responses, expectations and/or past experiences) and institutional factors (ethos of care, institutional culture, environment of setting). A systematic review by Rijnaard et al. (Reference Rijnaard, van Hoof, Janssen, Verbeek, Pocornie, Eijkelenboom, Beerens, Molony and Wouters2016) reported similar findings and concluded that nursing home residents’ ‘sense of home’ was influenced by three key factors: (a) psychological factors (sense of acknowledgement, preservation of one's habits and values, autonomy and coping); (b) social factors and activities (interaction and relationship with staff, residents, family, friends and pets); and (c) the built environment (private space, public space, personal belongings, interior design, the home's outdoor space and the neighbourhood).

The loss of one's home and its impact on one's sense of identity and belonging is particularly distressing for people moving into a care home (Westin and Danielson, Reference Westin and Danielson2007; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Simpson and Froggart2013). The move may also result in the loss of social and communication networks (Zamanzadeh et al., Reference Zamanzadeh, Rahmani, Pakpour, Chenoweth and Mohammadi2017), placing new residents at risk of loneliness and isolation (Brownie et al., Reference Brownie, Horstmanshof and Garbutt2014). As a result, having a sense of belonging and attachment to the nursing home has been identified as key to residents feeling ‘at home’ (Robertson and Fitzgerald, Reference Robertson and Fitzgerald2010; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Simpson and Froggart2013; Ryan and McKenna, Reference Ryan and McKenna2015). Fitzpatrick and Tzouvara (Reference Fitzpatrick and Tzouvara2019) used Meleis's Theory of Transition (Meleis, Reference Meleis2010) to explore facilitative and inhibitive influences on older people's transition to long-term care. Data synthesis of 34 studies identified that the transition featured potential personal and community-focused facilitators and inhibitors which were mapped to four themes: ‘resilience of the older person’, ‘interpersonal connections and relationships,’ ‘this is my new home’ and ‘the care facility as an organisation’. Lovatt's (Reference Lovatt2018) ethnographic study explored how residents (N = 11) in older people's residential accommodation experienced home and everyday life through their interactions with material culture. The study concluded that for residents, ‘becoming at home’ was an ongoing process, as evidenced through their social and material interactions. O'Neill et al. (Reference O'Neill, Ryan, Tracey and Lairdb) identified ‘the primacy of home’ as the core category in her grounded theory study which followed residents through the first year of their life in a care home. Robertson and Fitzgerald (Reference Robertson and Fitzgerald2010) reported that the experience of finding a new home in a care home ran parallel to maintaining connections with one's former home and community, and the extent to which staff facilitated this greatly impacted residents’ experiences of the transition.

It is widely recognised that institutional restrictions, standardised routines and strict risk management policies threaten an individual's independence and autonomy in care homes (Robertson and Fitzgerald, Reference Robertson and Fitzgerald2010; Paddock et al., Reference Paddock, Brown Wilson, Walshe and Todd2019; O'Neill et al., Reference O'Neill, Ryan, Tracey and Lairda). There is also evidence to suggest that many older adults like the routine of a care home and are happy to have staff on hand to attend to their needs (Koppitz et al., Reference Koppitz, Dreizler, Altherr, Bosshard, Naef and Imhof2017). Given the paucity of research on the views of nursing home residents and staff on the concept of a nursing homes as ‘home’, particularly in an Irish context, this study sought to address this imbalance.

Aim

The overall aim of this study was to explore the context of a nursing home as home from the perspective of residents and staff.

Design and method

Grounded theory was used in the collection of qualitative data from participating nursing home residents and staff. According to Corbin and Strauss (Reference Corbin and Strauss2008), grounded theory is an effective research approach where there is minimal knowledge of the phenomenon under investigation. Despite the plethora of studies on the transition to life in a nursing home, there remains a paucity of research on the concept of a nursing home as home from the perspective of residents and staff. A grounded theory approach, broadly consistent with the work of Strauss and Corbin (Reference Strauss and Corbin1998), was therefore chosen as it facilitated the development of a new perspective on the phenomenon of feeling at home in a nursing home.

Grounded theory as a methodology contends that theoretical concepts and hypotheses must emerge from the data, its main purpose being the exploration of social psychological processes for the purpose of developing substantive theories (Glaser and Strauss, Reference Glaser and Strauss1967). Consistent with grounded theory methodology, data collection and analysis using constant comparisons was an ongoing process in this study. Theoretical sampling is a process of data collection for generating theory whereby the analyst jointly collects, codes and analyses data and decides what data to collect next and where to find them, in order to develop a theory as it emerges. Glaser's (Reference Glaser1998) position in relation to theoretical sampling was that events and sites are selected after data collection has commenced in order to develop the emergent theory. In contrast, Strauss and Corbin (Reference Strauss and Corbin1998) argued that some sites and events may be selected in advance of data collection through purposive sampling. The main objective of a purposive sample is to produce a sample that can be logically assumed to be representative of the population. This approach is advocated within the empirical evidence to enable initial qualitative evidence synthesis (Benoot et al., Reference Benoot, Hannes and Bilsen2016; Armes et al., Reference Armes, Glenton and Lewin2019). As the proposal for the current study was submitted to funding bodies and to ethics committees, it was necessary to provide some indication of the proposed sample. Purposive sampling was therefore employed at the beginning of the study. Thereafter, data collection and analysis occurred simultaneously, and this informed the theoretical sampling used for the remainder of the study.

Sixteen focus group interviews were used to gather data from nursing home residents (N = 48) and staff (N = 44). Focus groups are broadly defined as in-depth, open-ended group discussions of one to two hours that explore a set of issues around a particular topic. The advantages of focus groups include the emergence of different opinions, the generation of new ideas and the ability to seek clarification on issues (Glasper and Rees, Reference Glasper and Rees2017). The focus groups in this study comprised between five and eight participants and no issues arose during the interviews. Disadvantages of this method, such as a dominant participant or researcher bias (Creswell and Creswell, Reference Creswell and Creswell2018), were minimised by the skilled and experienced researcher who moderated the groups.

Ethics and recruitment

Ethical approval was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of Ulster University. Letters of Invitation were sent to all Directors of Nursing for private, voluntary, individually owned and group-owned nursing homes registered in Ireland with Nursing Homes Ireland. From this dataset, a randomly selected group of homes was chosen for inclusion in data collection (N = 11). As there is evidence to suggest that the experience of moving to a care home may be different across geographical locations (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, McKenna and Slevin2012), the sample selection reflected a mix of urban and rural nursing homes. The eligibility criteria stipulated that participants must be able and willing to provide informed consent and agree to the recording of the focus group interviews. Eight Directors of Nursing agreed to participate and subsequently invited all residents and staff in their nursing homes to take part in the focus group interviews. Three nursing homes declined the invitation to participate. Participant Information Leaflets, issued to all participants, clarified the voluntary nature of participation and the procedure for recording and transcribing the interview data. Consent forms were signed by all participants prior to the commencement of the interviews.

Data analysis

The focus group interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. This facilitated note taking and the initial coding process. The software package NVivo 12 (QSR International, Melbourne) was used to assist in coding, storing, managing and retrieving data. Data were subject to three types of coding (Strauss and Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998). Open coding was the process through which concepts were identified and their properties and dimensions rediscovered in the data. In axial coding, categories were related to their sub-categories, to form more precise and complete explanations about phenomena. The final stage of coding, selective coding, was the process of integrating and refining categories and it was at this point that categories were organised around a central explanatory concept or key category (Strauss and Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998).

Ensuring rigour

Ahmed et al. (Reference Ahmed, Quraishi and Abdillahi2017) acknowledged that researchers’ inadequate description of their analytical process can impact the credibility of findings and rigour in the analysis of focus group data. The use of grounded theory methodology with its emphasis on constant comparative analysis and theoretical sampling were key in ensuring the credibility of this study's findings. Korstjensa and Moser (Reference Korstjensa and Moser2018) reaffirmed the earlier work of Guba and Lincoln (Reference Guba and Lincoln1989) in relation to credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability as quality criteria for qualitative research. Reflexivity, an examination of the possible influence of the researcher's beliefs and judgements on the research, is also a key quality indicator. In this study, reflexivity within the conduct of the focus group was maximised through the use of the researcher's reflexive notes, which allowed for further analysis of the setting and observations whilst listening to the audio-transcribed focus group notes (Korstjensa and Moser, Reference Korstjensa and Moser2018).

The initial interviews were recorded and checked to ensure the rigour of the data collection procedures. The constant comparative analysis of emerging data facilitated the verification of findings and minimised the likelihood of personal bias. The process of theoretical sampling continued until the emerging concepts and categories reached saturation. During the open and axial coding stages, two members of the research team (KM and AAR) independently viewed the original uncoded manuscripts and discussed their individual interpretation of emergent categories. After the selective coding process, the trustworthiness of the data was enhanced by the wider research team who further reviewed categories and sub-categories maximising credibility, dependability and confirmability (Lincoln and Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985). In keeping with one of the tenets of grounded theory (Corbin and Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2008), individuals’ own language at all levels of coding was used to ground the emergent theory in the data and, in doing so, to add to the credibility of findings.

Findings

Participants were drawn from a mix of urban (N = 4) and rural (N = 4) nursing homes. Table 1 shows the breakdown of participating nursing homes and residents. Eight focus groups were conducted with residents (N = 48) comprising 58.33 per cent females and 41.6 per cent males. The age range of residents was 35–98 years of age, with an average age of 78.21 years. Participating residents had lived in their nursing home from 4 months to 11.5 years and on average for 4.2 years.

Table 1. Nursing home and resident profile

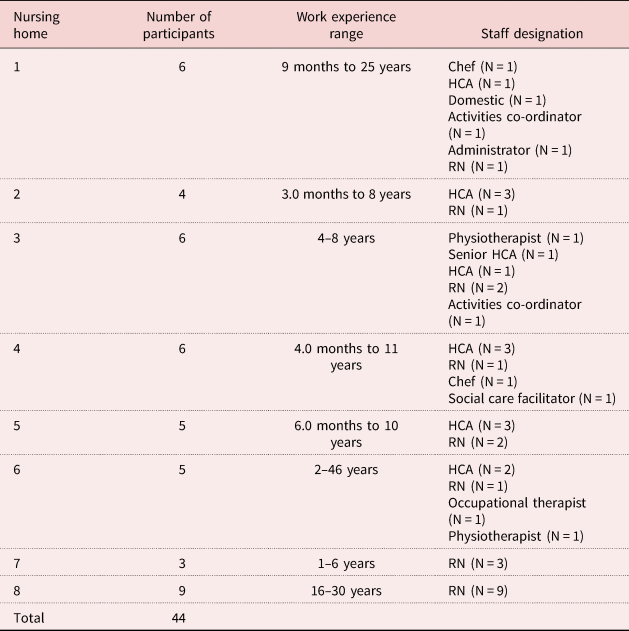

Eight focus groups were also conducted with nursing staff (N = 44). The staff sample included cooks, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, activity therapists, care assistants, registered nurses and administrative personnel. Table 2 provides details of staff designation by participating homes. The largest staff group was registered nurses (N = 20) and the next largest group comprised health-care assistants (N = 14). Just over a third (34%) of staff had less than five years’ experience and almost half (45.45%) had worked in the sector between six and ten years in total. A total of 11.36 per cent of the sample were very experienced members of staff who had worked in the sector for over 20 years.

Table 2. Staff designation and work experience

Notes: HCA: health-care assistant. RN: registered nurse.

Although the data from resident and staff interviews were presented separately in the initial draft of this paper, the authors noted more similarities than differences in both groups’ understanding of their nursing home as ‘home’. Presenting the data separately resulted in repetition and failed to capture the significant impact of the resident–staff relationship on residents’ feeling ‘at home’ in the nursing home. For this reason, data are presently jointly and distinctions between resident and staff findings are highlighted as required.

The reasons for moving into a nursing home were multi-factorial and are similar to those reported in the literature (Brownie et al., Reference Brownie, Horstmanshof and Garbutt2014; O'Neill et al., Reference O'Neill, Ryan, Tracey and Laird2020). These included a deterioration in physical and psychological health and wellbeing as evidenced by recurrent hospital admissions, falls, a need for 24-hour care, the inability to cope, loneliness, isolation and, particularly for people living alone, vulnerability and fear for personal safety. A lack of family support and a desire not to impose on their adult children or on friends and neighbours were also factors influencing the move. For some residents, a period of respite in the nursing home led to permanent residency. Others were considered by family members or health/social care staff as unfit to return home after a prolonged period of hospitalisation.

Five distinct categories captured the views of residents and staff on the concept of a nursing home as home. These were: (a) Starting off on the right foot, ‘First impressions can be the lasting ones; (b) Making new and maintaining existing connections, ‘There is great unity between staff and residents’; (c) The nursing home as home, ‘It's a bit like home from home for me’; (d) Intuitive knowing, ‘I don't even have to speak, she just knows’; and (e) Feeling at home in a regulated environment, ‘It takes the home away from nursing home’.

To protect the anonymity of participants, these categories are described in detail below using R and S abbreviations for residents and staff, respectively, with gender identification provided in the use of first name pseudonyms.

Starting off on the right foot: ‘First impressions can be the lasting ones’

Staff recognised the need to get things right at the outset as failing to do so could create a negative first impression. Many staff spoke of their own personal connection to and pride in the nursing home where they worked. One commented that ‘coming and staying here is important for us as a home’ (S39: Billie), while another referred to the home as ‘our’ home as evidenced below:

All I can say is that this place is home from home and 100 per cent here. We involve all of our residents in the decision making, they are truly autonomous. Moving into our home is a very important thing, we need to get it right as first impressions can be the lasting ones. (S13: Anne)

Coming and staying here is important for us as a home, so we do all we can to make the transition as smooth as possible. Choice, respect, listening to what they have to say and addressing any queries they have, especially if they think it's a bad thing to come here. (S39: Billie)

A key factor enabling residents to adapt to life in a care home was the extent to which staff appreciated the magnitude of the move and its impact on older people and their families. Staff spoke of the active steps they took to ensure a smooth transition. This included preparatory visits, good communication with potential residents and their families, and making sure that their room was as homely as possible:

Seeing [the home] for themselves, talking to other residents, staff or families. It all helps. It's respectful and dignified, as it should be. It might after all be their last move in their lives. (S21: Mary)

For residents, having a connection, however tenuous to the nursing home, appeared to be a key factor influencing their experience of the move. In rural areas, it was apparent that some residents specifically chose their nursing home based on the recommendation of others. There also appeared to be a sense of ‘personal knowing’ or ‘societal knowing’ of the home which was attributed to local knowledge or the ‘grapevine’. In some cases, residents had already visited other family members or friends in the home, and this was an important contributory factor in feeling a sense of connection to the home:

Two of my sisters had been in the home and died here and it is the nearest one to my area and I spent a fortnight here in 2006 convalescing, so I was familiar with it. (R42: Carol)

My husband's mother-in-law and cousin's mother-in-law all ended their days here so I thought maybe I would repeat the process. They were well taken care of. I had heard good reports about it from various people. It's important to get to know the ins and outs of the place beforehand, I think. (R44: Patsy)

Residents who did not have a connection to the homes appear to find the move more difficult and it took longer for them to settle in:

While we would all prefer our own home; things have changed, and we have to change with it. I wasn't happy when I came here at the start, but I had no choice, I was powerless to do anything about it as I had fallen at home on my own. Things are different now though, but it's taken a long time coming. (R33: Susan)

Starting off on the right foot meant recognising the needs of new residents for their own space and place within the nursing home. All of the residents interviewed valued their privacy and identified the significance of important gestures, such as staff knocking on their door prior to entry. Surrounding themselves with personal possessions also helped to create a more personalised and homely environment within the nursing homes:

Some of the residents will bring some of their own stuff from home, which is brilliant. The move is difficult for everyone concerned. They bring the pictures from home, so everything looks familiar and they are more comfortable. But having their own possessions, that's important. Choice and promoting independence also. Normally we would ask them about getting up in the morning, some are early risers, also some get up late, so we give them the choice. We have activities every day. They decide, we want this to become their new home. (S8: Seamus)

If I didn't have my room the way it is, it's my personality, and if I wasn't allowed to express that I would feel my room would be a dull place. You are encouraged to have it the way you want it … own furniture. To me anyway privatisation of your room is a big thing, you're encouraged. (R10: Nora)

For other residents, the transition, despite the best efforts of staff, was more difficult:

I have my bedroom set out with a lot of my own things, furniture, paintings, I have my bedroom set out like as if I was at home. I am independent and that's what makes it home for me. But even with all of this, it's not really the home that I want to remember; the home that I raised my children in; the home I waked my husband in; the home I loved so well with my dog. But this is it now for me, so I have to make the best of it, but if I could, and I'm sure we all would, we would go back to our own home in the morning to be sure. (R37: Ellen)

Making new and maintaining existing connections: ‘There is great unity between staff and residents’

Throughout the interviews, there was a strong belief that the concept of home was intrinsically linked to the extent to which staff and residents were connected to each other. For residents, having a sense of belonging within the nursing home helped them to feel at home. They spoke about the importance of maintaining connectivity with family and friends as being central to feeling at home in the nursing home. Contact with other residents also helped to reduce the isolation and loneliness some of them experienced in their own home:

I think there's a great sense of belonging with the other residents. They're very caring … once a month we have a concert in here and we enjoy that. I think this a great unity between staff and residents, and it speaks a lot for both the residents and the staff. (R28: Caroline)

I suppose it's as homely as you want it to be and if I see my sister, I will be excited and happy. Sometimes my friend comes to see me too and this makes me happy, you can go out too and have fun, makes you happy, you forget your own situation for a while, but sometimes even in this environment … (long pause) … that you still feel lonely and that you feel that more activities would help break the loneliness for you. (R9: Charlie)

Well I lived alone, and I see more people here during the day than many a day at home and I like doing my own thing and I'm allowed to do it. (R38: Nell)

Both residents and staff recognised the link between home and family. Staff referred to treating residents as members of their own family. There were many examples of genuine kindness where staff went above and beyond the call of duty to care for their residents and to make them feel special:

On Sunday, a lady told me she was going out on Tuesday. I do her hair for her and she asked me could I come in and I came in on my own time to do it because it gives them that wee bit of friendliness and that we are always there for them, try to help them out. We treat them like our own family. (S39: Billie)

Very early on in the interviews, participants emphasised the importance of relationships, making new ones and maintaining existing relationships with family, friends and the community. There was a general consensus among residents and staff that staffing levels within the home impacted on the time available to engage in activities and social outings. Low staffing levels meant that staff had to prioritise the physical needs of residents with social and psychological care taking second place:

We went out yesterday and that was once in many months. (R14: Annie)

Bingo, the little things we used to do, and we had a book club and we came down to the back sitting room and had singing and that, not now, so many staff have left. Sad really because it affects us. Now it's my iPad – I use my iPad all day. (R47: Marjorie)

Many staff spoke about how they worked in a positive manner to help residents adapt to their new environment. Again, the centrality of knowing the person's biography and life story and, more importantly, embedding this information into every aspect of care delivery, was key to person-centred care. Staff spoke about residents whom they felt adapted quite well to their new environment but also recognised that for others, the process of making new friends and maintaining connections to relatives and friends was more difficult.

On many occasions during the interview, both residents and staff referred to the nursing home as a family unit and their feeling of home depended on the extent to which they integrated into their new family. Staff spoke about treating residents as family members and residents spoke about how they grew to care for staff and subsequently were saddened when staff no longer worked in the home:

Staff are like our family; you grow to care about them, and you love them and then they're gone. Now I know that nobody can do anything about someone who wants to leave – there are reasons why they leave but there are reasons why they might stay. I'd say it's not the hard work that drives them away anyway. (R38: Nell)

I'd say the minute they come through the door; they're treated like a family member of my own. (S39: Billie)

The nursing home as home: ‘It's a bit like home from home for me’

When asked about feeling at home in the nursing home, many residents compared the nursing home with their home. Feeling that family and friends were welcome was important. Having people close by to recognise and tend to their needs in a respectful and dignified way led some residents to believe that the nursing home offered a better standard of care than that which they received at home:

Not only is this our home, our families are made so welcome when they come, it's like it's their home as well. My sister has her dogs with her, and nobody tells her to take them out. (R40: Margaret)

First of all, the surroundings. Inside you have the warmth of the rooms and the care that the girls give us … and a doctor coming in every week and a hairdresser every week, chiropodist when we want one. What more could you want? I didn't have this kind of caring in my own home. (R24: Rosita)

It's a bit like home from home for me, they do all they can to make me happy and feel valued and belonged here. I couldn't fault any of them. (R2: Eric)

One resident who felt restricted as a result of mobility problems while living at home felt equally restricted in the nursing home:

It compares a lot to your own home when you're not able to do things. (R41: Harry)

For others, feeling at home was a much more gradual process, requiring adaptation and acceptance of the inevitability of the changes associated with old age:

I still come back to the thing that old age changes things and that home is not what it was when we were younger. Life changes and you have got to change with it. (R5: Jimmy)

There was clear evidence of efforts by staff to promote the concept of home and a ‘homely experience’ for their residents. However, there were inherent challenges that needed to be overcome, as evidenced by this resident's feelings:

They can make it as close as possible to the real thing, but nothing replaces home. They can only do so much; it's a good nursing home and they do their best here. (R29: Eoin)

Some residents found aspects of communal living a particular challenge, especially in situations where the behaviour of other residents caused them upset. Staff were also aware of this and recognised the challenges and opportunities associated with the creation of a homely environment within the nursing home. They appeared to accept that for many residents, the nursing homes would never replace their own home, but they also recognised their responsibility in doing their best to create a homely environment:

As I see it many residents are going through a difficult time in their lives and our role is to take time with them, to demonstrate genuineness within our caring approach, to make them feel involved, to make them feel loved, to make them feel that they belong, so that they don't feel that this is their end. This is not the home they might want to be in, if they had a choice, but our role is to make it as homely as possible working alongside them in doing so. (S40: Carmel)

I always treat the resident as I would like to be treated, this is with dignity, respect, with manners. This helps them to settle in and eventually with all of their own things in place, they'll come to accept this as their home. We are all together in this. (S35: David)

Everyone is treated with respect, this is the residents’ home, lest we forget. We always ask for permission to come into their rooms, respect their privacy. We know when they're happy and the care is very good, we can tell by their faces if they're comfortable and relaxed. It's perhaps a fine art more than a science. (S3: Maeve)

Intuitive knowing: ‘I don't even have to speak, she just knows’

For residents, the description of staff as ‘genuinely caring’ was linked to a ‘sense of truly knowing’ and respecting the individuality’ of every resident, including those who had difficulties with verbal communication. An in-depth knowledge of residents’ likes, dislikes, food preferences, lifetime rituals and routines were incorporated into everyday practice. More often than not, it was often ‘the little things’ that appeared to enhance a sense of belonging and worth:

It really is the simple and small things they do for me that makes me happy. Doing my nails or helping me choose nice clothes to wear for mass. Yes, small things matter to me and lets me feel respected you see. (R32: Sylvia)

Residents reported that these nurses genuinely knew if they were having a bad day or felt down. They felt that they were able to pick up on nuances that perhaps hitherto only family members would have recognised:

Yes, [name] really knows me, my ups and downs. I don't even have to speak, she just knows. But then she's been at it a long time and has a sixth sense, very intuitive and caring. I feel her love and compassion for me as a person not just one of her residents. She can see past my crippled body in this wheelchair. Sometimes when I am just pondering the day, she'll just come and sit with me, hold my hand, share her experiences over a cuppa and a bit of home-made scone bread. Days like these, I can survive my pain. (R10: Nora)

Maintaining a level of independence also appeared to be a core component of individuality within the home, as was the importance of involvement and choice in decision making. Respecting residents’ choices was linked to how well the staff knew the residents and for many residents, truly knowing them as a person meant respecting them and promoting their independence:

The staff treat you like normal people, accept you for who you are, dignity as a person. They are so respectful, and they know us all so well. I personally couldn't ask for anything better really. They are so caring, now I mean genuinely caring. Why would I want to go home? (R24: Rosita)

All of the staff interviewed spoke of the importance of truly knowing their residents. Truly knowing somebody required an understanding and appreciation of the rich tapestry of their residents’ lives, past and present, what they did for a living, what they like to do now, what connections they have with family or significant others:

We treat the residents like we would want to be treated. We know their ‘ins’ and ‘outs’, their own little mannerisms, their ‘ups’ and ‘downs’. Knowing them and all about them is central to providing compassion with all we do. Respect for their diversity, their religion, their beliefs are all important to us. (S36: Kathleen)

Staff with a lot of experience, both in life and in nursing, appeared to be particularly attuned to the needs of more vulnerable residents. One Director of Nursing with caring experience as a mother and a daughter had a particularly good insight into the importance of spending time with residents and looking out for non-verbal cues. Residents in turn valued staff who empathised with their concerns and worries:

You know when things aren't right, they don't even need to tell you. Sometimes they'll say they're ok and you just know by looking at them and sensing that all is not ok. This is when time for them is essential, listening with empathy and concern. You never know what is going on unless you show genuineness and concern for the things that matter the most to them. And, sure some days it's major, like their bowels, and the next time, it's not so major, and they just want your company. That's ok too. This is why I became a nurse, because I do genuinely care for people. Showing that to my residents is my focus for care. (S38: Josie)

Truly knowing the person is important for me, even when they themselves can't find the words. I still know that they are communicating with me. I will always try to involve them and show respect for them. I will also try to promote a culture of residents’ needs first and foremost; despite the inherent difficulties it might cause. (S42: Susan)

Feeling at home in a regulated environment: ‘It takes the home away from nursing home’

Some residents demonstrated an awareness of the importance of standards within the home and were aware that the home was subject to inspection from the regulatory authority. A few indicated that they knew when the home was going to have an announced inspection as they felt that the anxiety levels of staff appeared to heighten around this time:

As I said, I have my own bedroom, and all set out like as if I was at home, but I am aware that it is a home that is subject to inspection at time. The staff always appear to be more anxious in preparation for such inspections and visits. (R44: Patsy)

For others, the nursing home's need to comply with standards and to safeguard residents, ran contrary to their need for autonomy and independence:

The locked doors, and then having to sign in and out are a pain. Why can't I go out on my own? … nurses tell me it's too risky. I do challenge them, and they tell me it's the rules. Whose rules I say? (R39: Liam)

If I could change things, I'd say the surroundings, move around, go anywhere you like, no restrictions. (R23: Jack)

There was unanimous agreement among staff about the importance of standard to safeguard residents and to provide assurances to the public about the welfare of families and friends in nursing homes. Some of the older staff participants, who had worked in nursing homes before the introduction of regulatory standards, were very firm in their belief that standards were necessary to assure the quality of care provision. However, there was a consensus among staff that there were now too many rules and regulations, and that the number and rigidity of the regulations ran contrary to the provision of homely care:

Rules can affect choice, like types of bed linen, mattresses, choices of furniture, all problematic if they are non-compliant with health and safety inspections or if they are not fire retardant. But all we can do is do our best, but I do think at times that it can take away from the homely environment the staff work hard to maintain. (S31: Noleen)

Sometimes the resident chooses to have the bed rails up because it makes them feel safe. We have involved the family in the decisions as well, and then the inspector makes out that this is not allowed. (S27: Sarah)

In some situations, while due cognisance was given to the need for standards, staff nonetheless felt that there was too much focus on clinical and medical matters which they perceived as detracting from a homely experience:

I think it's [standards] a very positive influence. I think sometimes they are trying to take us away from the homeliness. Thinking are they trying to bring nursing homes to be too clinical/medical. Holding our own at that end. Trying to keep away from being so clinical because I think that takes the home away from nursing home. (S18: Mandy)

Certain things we would be looking to keep things homely and they would be looking to bring in more evidence. You would think they are trying to make us look like a mini hospital instead of a nursing home. (S14: Marcella)

There was a general consensus among staff that inspectors were often insensitive to the demands and challenges they faced, particularly in relation to unexpected events and staff shortages. The Director of Nursing of one home that had a severe outbreak of flu prior to an inspection, felt that the degree of scrutiny by the inspector was excessive and that preparation for repeat inspections detracted from the time available to care for residents;

Every single staff member here and I felt many times that it's compromising the care of the resident by spending so much time with documentation. Myself, out of 8 hours if I count going back to [year], I wasn't even on the floor 15 minutes out of 8 hours just because I had to get the documentation right. (S25: Patricia-Ann)

It is important to note that it was not the requirement to uphold standards that was anxiety-provoking for staff but rather, the disconnect in terms of competing priorities of staff and, as they perceived it, of the inspectors:

Relatives, they are having mum or dad here and they are feeling safe, they're offered that at least and that this place is regulated so they will not be able to do anything without having adequate staffing and making sure we comply with all the safety regulations, infection control. There's a good point but sometimes it's too over the top that we are going through due to documentation and all that, that we are not giving 100 per cent of our time to the residents because we have so much documentation, to say what we did throughout the day. (S44: Eddie)

Discussion

This study explored the context of a nursing home as home from the perspective of residents (N = 48) and staff (N = 44). Study limitations include sample size and selection. The risk of sample bias is also recognised as it may have been the case that Directors of Nursing deliberately selected residents and staff within their homes who had a positive experience of living and working in a nursing home. It is also possible that with the focus of the study on home, residents who perhaps did not consider the nursing home as their home may not have come forward for recruitment to the study. Despite this, the study findings add to a growing body of knowledge on the enablers and inhibitors to feeling at home in a nursing home.

Five distinct categories captured the views and experiences of the residents and staff who took part in the study. These were: (a) Starting off on the right foot, ‘First impressions can be the lasting ones; (b) Making new and maintaining existing connections, ‘There is great unity between staff and residents’; (c) The nursing home as home, ‘It's a bit like home from home for me’; (d) Intuitive knowing, ‘I don't even have to speak, she just knows’; and (e) Feeling at home in a regulated environment, ‘It takes the home away from nursing home’. Together these five categories formed the basis of the core category ‘Knowing me, knowing you’, which captures the experiences of participants who repeatedly highlighted the importance of relationships and feelings of mutuality and respect between and among staff and residents as central to feeling at home in a nursing home.

Knowing me, knowing you

The findings of this study suggest that an intuitive knowledge and understanding of residents is central to the concept of homely care in nursing homes. The primacy of this knowledge and understanding was underpinned by dignity and respect, and valued by residents and staff alike. A caring approach that was embedded in and informed by ‘intuitively knowing the person’ was central to residents’ sense of identity, independence, belonging and to their experience of feeling at home in a nursing home. There was also evidence of reciprocity, insofar as staff knew their residents ‘ups and downs’, and this knowledge and understanding enabled them to anticipate and respond empathetically to their needs. Residents in turn greatly valued staff who were genuinely invested in their relationship with them. The reciprocity and mutuality associated with the core category ‘Knowing me, knowing you’, although valued by staff and residents, was at times challenged by staff shortages and time constraints.

Knowing, used frequently in everyday speech to refer to people and place, is an expression and a set of cultural practices (Degnen, Reference Degnen2013). In their study on rural family carers’ experience of the nursing home placement of an older adult, Ryan and McKenna (Reference Ryan and McKenna2015) reported that participants (N = 29) who were familiar with their local community and who knew other residents in the nursing home experienced a more positive transition than others. The theory that emerged suggested that familiarity was the key factor influencing rural family carers’ experience of the nursing home placement of an older relative. In a recent ethnographic study, Degnen (Reference Degnen2013) argued that the significance of knowing people and places in everyday life exceeds a simple ‘familiarity with’ or ‘knowledge of’. According to Degnen, ‘knowing people and places’ and ‘being known’ are relational aspects whereby people can be connected to (as well as disconnected from) each other through place or social memory. The significance of knowing and being known as highlighted in this study support the view that ‘by paying close attention to the complexities of knowing rather than dismissing it as simply a banal expression, we become attuned to the multiple overlapping registers that intertwine people, place, presence and absence’ (Degnen, Reference Degnen2013: 569).

In keeping with the findings of other studies (Hanratty et al., Reference Hanratty, Holmes, Lowson, Grande, Addington-Hall and Payne2012; Brownie et al., Reference Brownie, Horstmanshof and Garbutt2014; Križaj et al., Reference Križaj, Warren and Slade2016), many residents experienced loneliness prior to moving to the nursing home and the new relationships that developed between residents and staff significantly contributed to their ‘sense of home’. These relationships and the resultant ‘Knowing me, knowing you’ appeared to infiltrate all aspects of their life in the nursing home and were inextricably linked to their sense of autonomy, belonging and to the extent to which they felt at home with their new ‘nursing home family’.

The relationship between nursing home staff and residents is markedly different to relationships in other care settings where length of stay is often limited to days or weeks. Nakrem et al. (Reference Nakrem, Vinsnes, Harkless, Paulsen and Seim2013) acknowledged this in her identification of ambiguities concerning the role of a nursing home as (a) a home and a place to live, (b) a social environment, and (c) an institution where professional health care is provided and regulated. Nursing home residents, relatives and staff have more opportunities to get to know each other and the findings of this study suggest that when staff make a concerted effort to prioritise time to get to know their residents, this can be hugely influential in supporting residents to adapt to their new life in a nursing home.

Staff spoke about caring for the person as if they were a member of their own family. Residents, in turn, associated this ‘family status’ with high-quality, person-centred care. Almost half of the staff interviewed had worked in nursing homes between six and ten years, and valued their role in supporting some of the most vulnerable people in our society. In keeping with other studies (Dewar and McBride, Reference Dewar and McBride2017; Penney and Ryan, Reference Penney and Ryan2018), staff spoke about the personal fulfilment and satisfaction they derived from getting to know and care for their residents, despite the time and staffing constraints they faced. This deep level of ‘knowing’ their residents was further evidenced in their ability to see beyond the physical needs of the individuals in their care. For residents, the day-to-day routine of activities was important to their sense of belonging and feeling at home. Feeling part of a family was nurtured by the engagement of residents and staff in social activities and outings, which enabled them to get to know each other better.

While the findings of this study suggest that the creation of a ‘homely environment’ depends on staff and residents knowing each other, there was also evidence to suggest that a high turnover of staff can result in a loss of this intrinsic and intuitive ‘knowing’. Staff shortages (Siegel et al., Reference Siegel, Anderson, Calkin, Chu, Corazzini, Dellefield and Goodman2012) and a high turnover of staff (Koren, Reference Koren2010) have been reported as major barriers to the promotion of person-centred care and autonomy in care homes. Our findings broadly support these assertions as when staff–resident or resident–resident engagement was impacted due to staff shortages or the cancellation of activities or outings, this was difficult for all concerned. In a similar way, residents were saddened when staff, whom they had grown to know over time, resigned from their post in the nursing home.

The centrality of the relationship between residents and staff is embedded in the five themes that emerged from the data in this study and espoused in the core category ‘Knowing me, knowing you’. This suggests that recruiting and retaining staff with the right knowledge, skills and attitudes to support people in nursing homes is a key component in enhancing residents’ wellbeing and feeling at ‘home’ in a nursing home. This study did not examine a causal relationship between staff retention and feeling ‘at home’. However, the ‘Knowing me, knowing you’ core category suggests that a nursing home where staff are valued and rewarded (through proper remuneration and career development opportunities) may be more likely to recruit and retain staff with the knowledge, skills, attitudes and commitment to care for older people. Findings from our study suggest that this stability in staffing levels is more likely to facilitate the development of close relationships between residents, relatives and staff, which in turn may contribute to a more ‘homely’ nursing home environment.

Rights and risks in a regulated environment

There is a broad consensus in the literature that care home environments are unnecessarily restrictive (Fraher and Coffey, Reference Fraher and Coffey2011; Ellis and Rawson, Reference Ellis and Rawson2015; O'Neill et al., Reference O'Neill, Ryan, Tracey and Lairda). Our findings suggest a need to move from a ‘risk averse’ environment to a ‘risk aware’ one, where residents’ need for and right to autonomy, independence and choice are upheld with due consideration to potential risk. The internationally recognised ‘My Home Life’ programme, which aims to promote quality of life and positive change in care homes (https://myhomelife.org.uk/), is an example of ways in which collaboration with key stakeholders (residents/relatives/staff, home-owners, voluntary and statutory sectors, and regulatory bodies), can support culture change to give greater voice, choice and control to care home residents and their families (Penney and Ryan, Reference Penney and Ryan2018).

The World Health Organization (2018) advocates that international health systems need to be better organised around older people's needs and preferences, designed to enhance their intrinsic capacity and integrated across settings and care providers. Care homes are highly regulated environments and care staff must follow policy directives, guidelines and recommendations for best practice. Our findings show that this can create tension in facilitating residents’ freedom and autonomy, especially if staff believe that this places their residents at risk of harm. That said, there is a need to balance the human rights of residents, who have the capacity to do so, to take informed risks. Commissioning and regulatory bodies, in accordance with legislative changes around capacity, will be key drivers in influencing the way care services of the future are organised and delivered, and in stipulating specific practices aimed at protecting and promoting human rights.

Staff in our study demonstrated their understanding of the importance of routines within the home but also recognised the need to tailor these routines, where possible, to the choices of individual residents. The staff recognised that if residents were going to feel at home, there was a need to ensure that their lifetime rituals and routines continued to be respected after the move to the care home. This included mealtimes, choosing to lie in in the mornings, and for some residents, preferring to eat alone rather than in the dining areas. Despite this, some of the staff believed that rules and regulations imposed by the regulatory body, while motivated by concern for residents’ safety, resulted in a nursing home environment that was unnecessarily restrictive.

The findings of this study have implications for health and social policy, and for the organisation, management and inspection of nursing homes. With respect to care standards, staff unanimously supported the need for standards to safeguard vulnerable people and to assure the quality of care provision in nursing homes. Siegel et al. (Reference Siegel, Anderson, Calkin, Chu, Corazzini, Dellefield and Goodman2012) suggested that while regulations are well intended, providers may take a defensive approach by standardising care to meet regulations and ignoring the individual needs of care home residents. This appeared to pose a challenge to residents and staff who participated in the current study as there was a perception that the creation of a safe environment sometimes resulted in limitations to residents’ ability to come and go as they pleased. This suggests the need for a more open and honest debate between key stakeholders with a focus on balancing rights and risks within a regulated environment. Siegel et al. (Reference Siegel, Anderson, Calkin, Chu, Corazzini, Dellefield and Goodman2012) supported the need for closer and more collaborative working partnership between nursing home-owners, regulatory bodies, residents, relatives and care home staff with the aim of producing guidelines to facilitate the co-existence of a regulated and homely environment.

Home as a feeling and a place

According to Robertson and Fitzgerald (Reference Robertson and Fitzgerald2010), the meanings attached to a residential home are shaped by cultural, social and historical experiences, and are strongly influenced by management, with staff and residents adjusting to expectations as indicated by the social and physical environment. O'Neill et al. (Reference O'Neill, Ryan, Tracey and Lairda) argued that having ‘time’ for the resident and the family is the most important contribution that care home staff can make in building and maintaining a caring relationship. This time can be used to discuss problems, thoughts and feelings, and to provide stimulating activities for the resident. However, the availability of time has major implications for staffing levels and, as identified in this study, staff shortages can impact the time available for a more meaningful engagement with residents. This finding is supported by Nakrem et al. (Reference Nakrem, Vinsnes, Harkless, Paulsen and Seim2013), who stated that the challenge for nursing home staff is to meet the psycho-social and physical care needs of residents and, in doing so, to reconcile the tension of ‘home and not home’ in order to promote a sense of ‘at-homeness’. According to Nakrem et al. (Reference Nakrem, Vinsnes, Harkless, Paulsen and Seim2013), reconciling this tension will help nursing homes improve their residents’ feelings of ‘at-homeness’, thereby improving quality of life for residents, relatives and staff.

Establishing a sense of belonging or ‘finding home’ in a care home involves a process of adjustment (Cooney, Reference Cooney2012; Lindley and Wallace, Reference Lindley and Wallace2015), which has a significant psychological impact on residents (Marshall and Mackenzie, Reference Marshall and Mackenzie2008; Falk et al., Reference Falk, Wijk, Persson and Falk2013). The findings of this study resonate with the literature advocating person-centredness in long-term care settings, while also supporting the assertion by Cooney (Reference Cooney2012) that long-term care settings are first and foremost a resident's home but that moving beyond the technical and procedural aspects of care, can enable nurses to meet the holistic needs of the individual.

Conclusion

Our findings identified ‘Knowing me, knowing you’ as the core category underpinning the experiences of care home residents and staff in the context of the nursing home as their home. The significant role of nursing homes in the provision of a ‘home from home’ environment must be recognised and acknowledged. Our findings suggest that the recruitment and retention of staff who genuinely derive satisfaction from caring for vulnerable people is key to changing the public perception of care homes and of the people who work there. Our findings also have the potential to change the narrative around life in a care home. It would appear that the challenge is not to try to replace residents’ interpretation of ‘home’ (as experienced before the move to the nursing home) but rather to focus on creating a homely environment in the nursing home. If one subscribes to the belief that ‘home is not a place but a feeling’, perhaps the question is not whether the nursing home is perceived as the resident's home but rather whether it is perceived by them as their home now.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the nursing home residents and staff who participated in this study.

Financial support

This work was supported by Nursing Homes Ireland.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of Ulster University.