Introduction

Social connectedness is vital to maintaining health and wellbeing for many older adults. Ageing often brings life transitions such as changes in work, housing and social networks that can shape the quality and quantity of one's social connections. Social networks shrink and change over time for older adults due to death of family and friends, limited mobility and other health limitations (Perkins et al., Reference Perkins, Ball, Kemp, Hollingsworth and Pruchno2013; Isherwood et al., Reference Isherwood, King and Luszcz2017). Social connections further vary among older adults who age in place at home rather than in an assisted living community (Lawrence and Schille Schigelone, Reference Lawrence and Schille Schigelone2002; Isherwood et al., Reference Isherwood, King and Luszcz2017; Pirhonen et al., Reference Pirhonen, Tiilikainen and Pietila2018). Given ample evidence that women outlive men (e.g. Austad, Reference Austad2006; Seifarth et al., Reference Seifarth, McGowan and Milne2012; Zarulli et al., Reference Zarulli, Barthold Jones, Oksuzyan, Lindahl-Jacobsen, Christensen and Vaupel2018), older heterosexual women are more likely to live alone and face additional disruptions in social networks after a spouse dies. This aspect of older women's lives merits scholarly attention (Chumbler et al., Reference Chumbler, Grimm, Cody and Beck2003; Papastavrou et al., Reference Papastavrou, Kalokerinou, Papacostas, Tsangri and Sourtzi2007). The COVID-19 pandemic has only underscored the importance of social connectedness.

This study will focus on social connectedness and perceived isolation as concepts that capture a person's integration into the social world and their subjective evaluation of their current state of connectedness. The literature frequently ties these two concepts to each other. Zavaleta et al. (Reference Zavaleta, Kim and Mills2014) defined social connectedness as the quantity and quality of social relations, as opposed to social isolation, which they defined as the deprivation of social connectedness. They measured social isolation on four levels: individual (spouse, family members, co-workers, friends), group (church, trade union, club), community (neighbourhood, village, ethnic community) and the larger social environment (regional identity, institutions, politics). Cornwell and Waite (Reference Cornwell and Waite2009) distinguished the concepts of social connectedness and social isolation from each other. They use the term social disconnectedness to describe a lack of connectedness to individuals and social groups. They argue for the evaluation of perceived isolation to measure the perceived inadequacy of the quantity and quality of a person's social relations relative to their desired quantity and quality of social relations. Andersson (Reference Andersson1998) differentiated isolation from loneliness, which he defined as an unpleasant state of psychological distress that results from a discrepancy between the actual and desired quantity and quality of social relations. Although loneliness will not be used as a key concept in this study, it is caused by perceived isolation, and thus an important indicator of the concept. For a breakdown of key terms, see Table 1.

Table 1. Key terms

Social isolation has been found to be associated with increased risk of mortality (Holt-Lunstad et al., Reference Holt-Lunstad, Smith and Layton2010, Reference Holt-Lunstad, Smith, Baker, Harris and Stephenson2015; Steptoe et al., Reference Steptoe, Shankar, Demakakos and Wardle2013), poorer health (Cornwell and Waite, Reference Cornwell and Waite2009; Coyle and Dugan, Reference Coyle and Dugan2012) and poorer cognitive function (Shankar et al., Reference Shankar, Hamer, McMunn and Steptoe2013) among older adults living in the community. Physical distancing during COVID-19 has only exacerbated social isolation and the decreases in mental health associated with social isolation in older adults (Robb et al., Reference Robb, de Jager, Ahmadi-Abhari, Giannakopoulou, Udeh-Momoh, McKeand, Price, Car, Majeed, Ward and Middleton2020).

Relatedly, one's perception of social isolation can shape health and wellbeing. Researchers have found that perceived isolation or loneliness is associated with poorer physical health (Cornwell and Waite, Reference Cornwell and Waite2009) and poorer mental health (Coyle and Dugan, Reference Coyle and Dugan2012), including more depressive symptoms and psychological distress (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Taylor, Nguyen and Chatters2018) and poorer cognitive function (Shankar et al., Reference Shankar, Hamer, McMunn and Steptoe2013) among older adults living in the community. One study of Finnish older adults in assisted living found that perceived social isolation was connected to external and internal interactions within the facility (Pirhonen et al., Reference Pirhonen, Tiilikainen and Pietila2018). Residents' perceptions of social isolation varied according to the quality of social interactions with co-residents and staff, daily routines at the institution and residents' personal life stories, and older friends who avoided visiting them at their facility home (Pirhonen et al., Reference Pirhonen, Tiilikainen and Pietila2018).

Perceived isolation can be difficult to capture because it depends on the individual's subjective evaluation of the discrepancy between their actual and ideal social connectedness. More important than the quantity of network members or frequency of contact are feelings of social integration and the availability of companionship or an emotional attachment figure. An individual can feel isolated while surrounded by others or socially connected while alone (Zavaleta et al., Reference Zavaleta, Kim and Mills2014). Such experiences have been brought to the forefront for people of all ages in light of physical distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although perceived isolation is difficult to evaluate from an objective perspective, it is important in understanding social experiences from the point of view of the population of interest. Especially in the case of older adults, who are believed to be at greater risk of isolation and loneliness, it is important for researchers to take individual, subjective experiences into account to understand how circumstances affect individuals' evaluation of their lives, and how this evaluation affects their approach to managing their social connectedness.

Gender also plays a role in social isolation and loneliness. While being male is associated with social isolation (Cudjoe et al., Reference Cudjoe, Roth, Szanton, Wolff, Boyd and Thorpe2020), some researchers have found that loneliness is more common among older women than men (Steptoe et al., Reference Steptoe, Shankar, Demakakos and Wardle2013). Older women and those who are single, widowed or divorced and report feelings of loneliness have also reported feeling worse regarding depression and anxiety compared to older peers (Robb et al., Reference Robb, de Jager, Ahmadi-Abhari, Giannakopoulou, Udeh-Momoh, McKeand, Price, Car, Majeed, Ward and Middleton2020).

Objective measures of social isolation and perceived isolation or loneliness are often related. One cardiovascular health study found that higher levels of social isolation and certain life events (e.g. death of a friend) are associated with higher odds of loneliness (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Kaye, Jacobs, Quinones, Dodge, Arnold and Thielke2016). Other research has found that older adults with objective social isolation have worse symptoms of sleep disturbance, depression and fatigue when they also experience subjective social isolation (Cho et al., Reference Cho, Olmstead, Choi, Carrillo, Seeman and Irwin2019). Given the relationship between social isolation and loneliness, researchers have called for more attention to both social disconnectedness and perceived isolation, simultaneously (Cornwell and Waite, Reference Cornwell and Waite2009).

Research underscores the benefits of social relationships and social activity on cognitive function (Yeh and Liu, Reference Yeh and Liu2003; Holtzman et al., Reference Holtzman, Rebok, Saczynski, Kouzis, Wilcox Doyle and Eaton2004; Ertel et al., Reference Ertel, Glymour and Berkman2008; Krueger et al., Reference Krueger, Wilson, Kamenetsky, Barnes, Bienias and Bennett2009), physical health (Belanger et al., Reference Belanger, Ahmed, Vafaei, Curcio, Phillips and Zunzunegui2016), mental health (Boen et al., Reference Boen, Dalgard and Bjertness2012; Belanger et al., Reference Belanger, Ahmed, Vafaei, Curcio, Phillips and Zunzunegui2016) and prevention of loneliness (Kwag et al., Reference Kwag, Martin, Russell, Franke and Kohut2011; Chen and Feeley, Reference Chen and Feeley2014). However, evolving social support systems for older adults, and older women in particular, may create additional challenges as their life circumstances change. Need for and access to formal and informal care-givers can shape the types of social support that older adults receive (Isherwood et al., Reference Isherwood, King and Luszcz2017) and how they respond to that support. Older adults who place high value on independence and autonomy may struggle to accept support from others (Lawrence and Schille Schigelone, Reference Lawrence and Schille Schigelone2002), despite potential mental and physical health benefits. Research with older adults in continuing care communities further suggests the evolution of creative support networks through buddy systems and reciprocal assistance among older adult neighbours (Lawrence and Schille Schigelone, Reference Lawrence and Schille Schigelone2002). Given research on gender differences associated with loneliness, social isolation and mental health (e.g. Robb et al., Reference Robb, de Jager, Ahmadi-Abhari, Giannakopoulou, Udeh-Momoh, McKeand, Price, Car, Majeed, Ward and Middleton2020), more research is warranted that examines the experiences of older women. Social connectedness and perceived social isolation provide an important lens through which to examine these experiences, particularly as the world continues to experience the effects of a global pandemic that has dramatically shaped and reshaped social connections and support.

We selected a sample of middle-old and old-old unmarried women based on risk factors for loneliness. Older women have reported higher loneliness than men (Robb et al., Reference Robb, de Jager, Ahmadi-Abhari, Giannakopoulou, Udeh-Momoh, McKeand, Price, Car, Majeed, Ward and Middleton2020). Middle-old and old-old age groups are associated with higher rates of loneliness than the young-old (aged 65–74 years) (Andersson, Reference Andersson1998; Little and McGivern, Reference Little and McGivern2014). An unmarried status (single, separated, divorced or widowed) is associated with greater risk of loneliness (Andersson, Reference Andersson1998). Though living alone does not equate to loneliness, it is critical to one of the goals of this study: to explore how older adults maintain social connectedness despite barriers to its accessibility.

This study takes a closer look at the experiences of social connectedness and perceived social isolation of older women by comparing the experiences of those living in their own private homes and those living in assisted living facilities. The quality, quantity and access to various relationships and social connections may vary depending on these living circumstances.

Therefore, this study asks the following questions:

• How do older women (aged 75+ years) experience social connectedness and perceived isolation?

• How does this experience vary between older women living alone in private homes and those living in assisted living facilities?

Methods

This study compares the experience of social connectedness between older women who live alone in their own homes and older women who live in assisted living facilities. For the purposes of this study, social connectedness is defined as the quantity and quality of social relations at the level of the individual, group, community and larger social environment, based on the review of social isolation literature by Zavaleta et al. (Reference Zavaleta, Kim and Mills2014). Perceived isolation is indicated by the degree of misalignment between actual and desired quantity and quality of social relations at the same levels, based on Cornwell and Waite's (Reference Cornwell and Waite2009) analysis of social connectedness and perceived isolation data from the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project. Though there is much variation in the characteristics and services offered by assisted living facilities, The Assisted Living Quality Coalition published a definition in 2003: an assisted living facility provides 24/7 services and oversight, provides services to meet the scheduled and unscheduled needs of residents and facilitate ageing in place, provides or arranges care and services to promote independence, emphasises consumer autonomy, dignity and choice, and emphasises privacy and a homelike environment (Hawes et al., Reference Hawes, Phillips, Rose, Holan and Sherman2003). According to Hawes et al. (Reference Hawes, Phillips, Rose, Holan and Sherman2003), assisted living facilities should provide at least a basic level of service, including 24/7 oversight, housekeeping, at least two meals a day and assistance with at least two activities of daily living. This study contrasts older women in assisted living facilities with older women who receive a basic level of care while living in their own private home. This care comes from external sources as they live in standalone houses (i.e. not in any sort of communal building) and without any other residents in the house.

Research design

This study is an iterative analysis of semi-structured qualitative interviews with two comparison groups. The first author collected data. All interviews took place in participants' homes or their rooms in their housing facility. The first author conducted one- to two-hour semi-structured qualitative interviews based on an interview guide developed by both authors. The interview questions were in part adapted from quantitative questions proposed by Zavaleta et al. (Reference Zavaleta, Kim and Mills2014) to measure social isolation, a social disconnectedness scale by Cornwell and Waite (Reference Cornwell and Waite2009), a qualitative assessment of the needs and coping resources of vulnerable older adults (Lawrence-Jacobson, Reference Lawrence-Jacobson2018) and a study which explored how older adults' social networks changed after moving to an assisted living facility (Berlin, Reference Berlin2018). Participants were compensated for their time with a US $15 gift card. The authors had extensive conversations about the strengths and limitations of offering incentive gift cards for participation. The goal of this study was to understand the experiences of older adults whose voices are often rendered invisible, given a dearth of research on this population. Given this goal, the researchers decided to compensate participants for their time and contribution. This decision helped characterise the interview as a reciprocal interaction.

The qualitative interview guide consisted of the following sections: framing the interview, social connectedness, perceived isolation and wrap up, followed by a post-interview survey. The framing section began by asking participants to discuss where they currently lived and related decisions and transitions (especially if they lived in or had considered moving to assisted living), then explain how their daily life played out inside and outside the home, and touch on health-related or other challenges that limited their daily activities. The social connectedness section asked about participants' relationships with individuals, groups, communities and the larger social environment. Within these topics of social connectedness, the individuals section included subsections on family and care-givers (including aides at assisted living facilities). Groups included subsections on formal and informal groups. Each social connectedness section examined the characteristics of the individuals, groups and communities, and aspects of the larger social environment that participants felt connected to, how those relationships played out in their current life, how they had changed as they aged or since they had moved to assisted living and how they compared to participants' desired level of connectedness. The perceived isolation section asked about lack of desired connectedness or feelings of loneliness. The interview concluded by asking participants if they would like to add or elaborate on anything else about their feelings of social connectedness.

After the qualitative interview, the first author administered a brief survey to collect demographic information. The survey also asked participants to list their current relationships with individuals and membership in organised groups, modes of transportation and health challenges that limited their daily activities. While the qualitative interview guide had already covered these data points, the purpose of the post-interview survey was to quantify factors that had been described in narrative form throughout the interview. The structure of the qualitative interview probed participants to consider relationships, groups, transportation resources and health challenges that may not have come to mind had they been asked to list them outright. After data collection, the authors determined that the quantitative data on relationships, groups and health challenges did not add meaningful perspective to analysis of the qualitative data, given the scope of this particular project. The remaining data from post-interview surveys (transportation modes, age, marital status, sexual orientation, race and ethnicity, employment status and field of employment) were included as demographic characteristics as opposed to quantitative data and provide potential avenues for future research. Therefore, this study is characterised as qualitative only, not mixed-methods.

To recruit participants living in their own homes, we contacted community leaders and senior service professionals at social service agencies, religious institutions or other organisations that serve older adults (i.e. senior centres, churches). Some of these contacts publicly posted the recruitment flyer. Some connected us with people who they believed matched the study criteria. One participant had been previously interviewed by the first author for a different study. Many participants were recommended through personal connections or by other participants.

To recruit participants in assisted living, we sent an explanation of the study to local assisted living and multi-level care facility administrators with a request to post the recruitment flyers in their facility or to recommend specific residents. All eight participants were recommended by facility administrators, saw the flyer posted or were recommended by other participants who lived in the same facility. The participants lived in three different assisted living facilities.

One implication of this comparison by living arrangement is that assisted living and community dwelling designations are not static categories. Older adults transition between the two. Several participants had recently moved to assisted living, planned to return to their private homes or had considered moving to assisted living.

Three additional interviews were excluded from analysis. The first interview became a pilot interview after the authors changed the interview guide in response to that participant's feedback. Two other participants were selected with the understanding that they lived in an independent condominium and the assisted living section of a multi-level care facility, respectively. During the course of the interview, the first author learned that the former actually lived in an age-restricted community which was intentionally structured to encourage interactions between older adults. The latter was revealed to live in the independent section of the multi-level care facility, as opposed to the assisted living section.

Ethical issues

Given the population involved in this study, the co-authors regularly discussed ethical implications of the research with senior colleagues when designing the study and incorporated measures to minimise potential risk and breach of confidentiality and to preserve participant autonomy. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Michigan granted an exemption for this study under 2(i) and/or 2(ii) at 45 CFR 46.104(d). The IRB determined that this research only includes interactions involving survey procedures and/or observation in which the information was recorded in a manner that the identity of the participants cannot be readily ascertained directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects. Furthermore, any disclosure of the participants' responses outside the research would not reasonably place participants at risk of criminal or civil liability or be damaging to the subjects' financial standing, employability, educational advancement or reputation. Participants provided informed consent to participate in the study and to permit audio recordings of their interview with the understanding that they could choose not to participate, to withhold information or refrain from answering questions, or to end their participation at any point without penalty. Participants were assured that no identifying information would be shared about them.

Although release of information obtained in this study would not pose a direct threat to the participant, the authors considered potential implications if identifying information were accidentally disclosed. Co-authors also discussed concerns about privacy of participants' reflections about their social connections and potential social retaliation. To minimise this risk, the authors assigned participant ID numbers to audio recordings, interview transcripts and demographic survey answers. This paper uses pseudonyms and generalised references to community connections to protect participants from identification.

The delicate nature of studying a population which is often targeted for financial and other exploitation was evident from the gatekeepers who mediated recruitment for many of the participants and potential participants. Gatekeepers included people such as facility administrators, social workers, family and friends. Some may have withheld individuals they perceived as vulnerable from participation in the study. The concern of gatekeepers was evident in the recruitment process mediated by one participant's son, who asked to see the interview questions before providing his mother's contact information. The son made clear his expectation that an interview with an older woman living alone should be handled carefully. These gatekeepers were understandably hesitant to facilitate a situation in which an interviewer would enter the home of an older woman who lived alone to learn about her daily activities and challenges, which someone with malicious intent could exploit. Ultimately, the authors believe that such gatekeepers contributed to a more trusting and comfortable rapport between the authors and participants. While the gatekeeping further ensured protection of some of the participants, it could have also prevented some older adults who ultimately wanted to participate from doing so, so their voices may not be represented in this research.

Analysis

After each interview and throughout the data collection and transcription period, the first author produced memos to record notable observations, summarise emergent themes, and identify key ideas and connections to other interviews. The memos also included similarities and differences among the interviews to allow for comparisons between the two groups. Both authors regularly met to discuss findings from the memos and connections and emergent themes from the interviews. The first author transcribed all 19 interviews verbatim. The first author reread all interview transcripts for another round of thematic annotations. After the core themes were outlined, the first author again reread all interview transcripts to corroborate the data and examine contextual differences behind contrasting data. Data were included from a subset of the post-interview survey questions for descriptive purposes. The remainder of the survey questions were excluded because the qualitative interview already substantially covered those topics. To increase research rigour and triangulation, both authors regularly met to discuss data collection, coding, analysis and research memos.

Reflexivity is an important part of qualitative research (Day, Reference Day2012; Gabriel, Reference Gabriel2015; Probst, Reference Probst2015) and was an important part of the data analysis. Reflexivity requires the researchers to engage in ‘self-location’ (Rankl et al., Reference Rankl, Johnson and Vindrola-Padros2021) regarding gender, class, ethnicity, and other social locations or positionalities, and one's interests, assumptions and life experiences shape how a researcher approaches participants in a study and the knowledge produced. Here, the researchers reflected deeply on their own social identities regarding gender, age and ability. For example, the researcher interviewing the participants was much younger than the older women participants, which may have shaped rapport with the participants in diverse ways as well as data analysis and interpretation. Triangulating data was particularly helpful during data analysis, particularly the use of multiple generational lenses on the data (i.e. the researchers are from different age cohorts) and life and work experiences working with older women.

Findings

Participants

The 16 participants were unmarried middle-old (aged 75–84 years) and old-old (aged 85+ years) women. Eight of the participants lived alone in private homes. The other eight participants lived in an assisted living facility or the assisted living section of a multi-level care facility. For a description of demographic characteristics, employment and driving status, see Table 2.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of participants

Notes: N = 16. 1. One participant was widowed and had also been divorced from a previous partner. 2. One participant was both retired and a former homemaker or stay-at-home parent.

Eight participants lived in three different assisted living facilities or the assisted living section of multi-level care facilities. The study excluded higher-level senior residential care facilities, such as skilled nursing homes, because of the higher level of care-giving need. Assisted living facilities fall on the lower end of the care-giving spectrum, meaning most residents should be able to complete at least some activities of daily living independently.

Eight participants lived alone in their own homes (condominiums or standalone houses). The authors aimed to recruit participants who mirrored the typical lifestyle characteristics of older women living in assisted living facilities. Participants living in their own homes lead generally more independent lifestyles relative to the participants in assisted living. Half of the participants living in their own homes still drove compared to two participants in assisted living.

All participants living in their own homes met at least one of the following criteria: they needed assistance with at least one activity of daily living (dressing, bathing, feeding, going to the toilet, grooming, oral care, walking or using a wheelchair), needed assistance with at least one instrumental activity of daily living (housekeeping, laundry, changing linens, shopping, transportation, meal preparation, managing money, managing medications), received in-home care, or had previously or were currently considering moving to an assisted living facility. None required 24-hour care.

Interviews

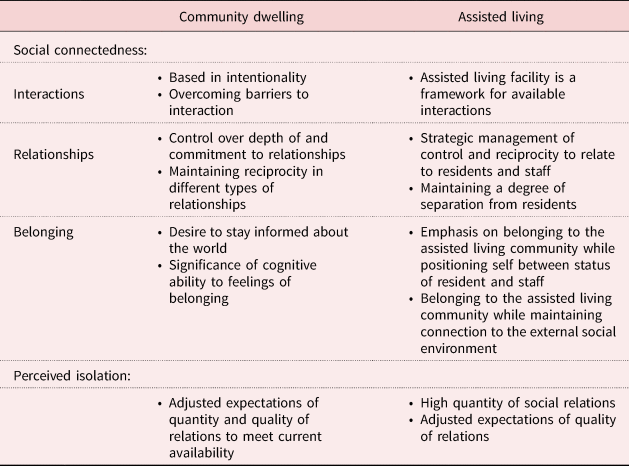

This comparative study reveals different experiences of social connectedness between women living alone in private homes and in assisted living. Three main themes relating to social connectedness emerged from the interviews: interactions, relationships and belonging. Overall, this study revealed a shared lack of perceived isolation between the two groups. These findings are outlined in Table 3.

Table 3. Summary of findings

Notes: The findings centred on experiences of social connectedness and perceived isolation. Three categorical themes emerged around social connectedness: interactions, relationships and belonging. The comparison between women living in private homes and those living in assisted living facilities can be broadly summarised as intentionality versus availability, especially regarding interactions. Their expressions of relationships and belonging were more nuanced in how each leveraged control and reciprocity in their individual relationships and expressed a sense of belonging to groups and communities, as well as the larger social environment. Both groups showed a surprisingly similar lack of perceived isolation, thanks to the tendency to adjust expectations in terms of quantity and quality of social relations.

Interactions

Community dwelling (private home). The experiences of social connectedness for participants living in their own homes were largely characterised by intentionality. They devoted attention and resources to overcoming barriers to interaction, including their own barriers and others' barriers. Driving was one of the most prevalent examples of this theme. Most participants living in their own homes did not drive or their driving was restricted. This made casual and spontaneous interactions difficult to come by, as Edith (all names have been changed for participant confidentiality) explained:

I have a driver, but of course, she has other customers too. So if I make an appointment at the doctors, then I may call her and tell her, and it's not good for her. I have to kind of co-ordinate things more than I used to … It's a challenge, but generally with a little planning it works out. If I'm making a doctor's appointment, I can check with her, the driver, and see what times are good for [her]. And then when I make the appointment, I know that it's going to be good for her. But it does take a little advanced thinking, which normally, I was the only one that I had to think about, my schedule. So that works out. But like I said, I can't just make the phone call and know that it's a done deal.

These participants utilised a few options to access interactions outside their home. For instance, if a participant wanted to attend church but could not drive herself, she could hire a driver or taxi to take her to church. She could have someone she knew drop her off as a favour even if they did not go to church with her; or she could get a ride with someone else who went to her church. Getting a ride to an interaction with someone else who would attend the interaction represents a theme we call ‘positive mediated interactions’. A positive mediated interaction occurs when a pre-existing relationship facilitates an interaction in which a person otherwise would not have engaged. Positive mediated interactions often supported the continuing interactions of participants living in their own homes with groups or communities they valued as barriers to interaction accumulated, as with Shirley's writing group:

[My friend] usually picks me up, but she's gone. The other person who picks me up sometimes – it's at her house. So, a woman who lives in [nearby city] and drives in, unless we go to her house, is gonna pick me up … So, they make accommodations. If she weren't coming or couldn't do it, [group member], whose house it is, I know would drop everything and pick me up.

Assisted living. The social connectedness experiences for participants in assisted living were largely characterised by the availability of interactions within the assisted living facility. The structure of the facility provided an abundance of people to interact with, plus spaces and opportunities for interaction. The assisted living facility eliminated many of the barriers to interaction faced by participants living alone in their own homes. Transportation was a less-prevalent barrier to interaction since most of their meals, activities and often even religious services took place inside the facility. Participants in assisted living could attend facility activities or just chat with staff and neighbours in a communal area no matter the time of day or season. Arlene made a friend by bumping into her while they were both waiting for the elevator. Wendy described how she took advantage of facility operations to organise her interactions:

I enjoy dinner ’cause I like the contact with the other people. And I always invite – most people just go down. They routinely eat with the same people. I like to eat with different people. So, I make my own plans. I keep a calendar and I invite people to join me for dinner.

While participants in assisted living could easily seek out desired interaction, unwanted interaction was difficult to avoid. Staff freely entered their rooms to administer medications or check on residents at unanticipated or unwelcome times. These participants also reported some negative or burdensome interactions with other residents. Some fellow residents were difficult to communicate with or caused disturbances because of disabilities or disposition. As one way to counteract undesired interactions, people who lived in the assisted living facility rarely visited each other in their rooms. Arlene had been welcoming to one resident when the woman initially moved in, but she clung to Arlene as she struggled to adapt to life in the assisted living facility. Arlene could not shake the woman, who even violated that facility social norm by visiting Arlene's room uninvited.

Participants living in their own homes wielded more control over unwanted interactions than participants in assisted living who shared living space with the people they wanted to avoid. In contrast to the positive mediated interactions experienced by participants living in their own homes, participants in assisted living benefited from negative mediated interactions. These happened when existing relationships (usually with staff) allowed participants to avoid unwanted interactions that they otherwise might not have been able to escape. Given the staff's authority over facility dynamics, they could either directly manipulate interactions (i.e. sit people who caused disruptions elsewhere at meals) or communicate with people who received complaints.

Relationships

Community dwelling. Participants living in their own homes focused on control and reciprocity to maintain relationships. These qualities were critical to their sense of self and feelings of belonging to the larger social environment. They acted on control and reciprocity in different ways depending on the type of relationship, including managing the closeness of less-desirable relationships. This mirrors negative mediated interactions to avoid undesirable interactions in assisted living. However, this theme highlights casual relationships that participants living in their own homes did not wish to deepen as well as potential new relationships that did not interest them. In such cases, these participants reflected that they already had and grieved their very close, meaningful relationships (siblings, spouses, longtime friends, etc.). These participants viewed any new or current relationships that were not very close to begin with as the fringes of their social life, not its core. Some participants implied that they indulge these fringe relationships for others but preferred to keep them at arm's length. Bonnie described one such relationship:

I don't pursue anything with them. If they call, I invite them, ‘come on over’. Sometimes, they'll pick up a lunch and bring it in. And they're nice people. But I'm not gonna pursue anything with them.

Bonnie further explained why she did not feel the need to pursue such peripheral relationships, despite her limited quantity of social relations:

I feel I don't need the social interaction. If I have social interaction, I want it to be top notch. And you don't find that many top-notch people in your life, really quality people. I've had some really quality people in my life. A lot of these others don't measure up.

Conversely, participants living in their own homes dwelled on how and how much they input into relationships from which they sought or needed greater output than those fringe relationships. This careful control of relationships preserved relationship reciprocity (the equal input and output by both parties in a relationship). These participants leveraged instrumental resources, as well as their own relative health and independence, to contribute equally to different types of relationships: older adult peers who were more dependent, those who were more independent, formal care/service providers whose sole intended roles were to provide instrumental support, and adult children who could potentially sway participants' trajectories as they aged. Susan described her give and take with her friends who no longer drove:

They said I should put a thing in my car like for a cab. There's two or three of them. In fact, one of them has me for dinner every so often as payback for picking her up.

In their examples of helping more-dependent friends cope with ageing-related challenges, participants discussed taking attention away from their friends' challenges to prevent feelings of inferiority, which could imbalance feelings of relationship reciprocity. With more independent friends, participants tried not to take advantage of their support lest they imbalance relationship reciprocity in the other direction. When Shirley's more independent friends implored her to use a wheelchair on their outings even though she preferred to walk, Shirley recalled a late friend who had slowed down their outings with the same refusal. Shirley conceded to the wheelchair for fear of instilling that same frustration in her friends.

Relationship reciprocity with formal care/service providers required more creativity because of the unidirectional input from provider to recipient with the expectation only of monetary compensation. Some participants gifted material resources to care/service providers (even to those who furnished their resources). Edith's driver sometimes did her grocery shopping. When she brought Edith some canned food that was too high in sodium, Edith in turn gifted some of the food back to her driver, as well as to her housekeeper. Edith warmly reported the gratitude that each expressed for the small gift.

Some of these formal provider–recipient relationships morphed into pseudo-friendships. Participants expressed a devotion to these providers that motivated them to enhance the relationship however they could. They would hire their regular providers under the table (to get around agencies) or refer them to others. Edith's family practically employed her housecleaner fulltime between all of Edith's referrals.

Assisted living. Participants in assisted living also valued control and reciprocity as meaningful to their sense of self and feelings of belonging. They told similar stories of helping fellow older adults living in the facility cope with their respective challenges, as well as helping facility staff. Margaret, who had dealt with her husband's illness and death, described offering support to a neighbour in the midst of a similar experience and her expectation of a budding friendship:

The lady in the next room. [Her husband] has a neurological imbalance … And their older son, 45, had a heart attack and died. So, I have something to offer her if she's feeling like she needs a hug or something. I look forward to her coming and visiting sometime.

The quantity of staff, limited access to outside goods, and rules and ethical implications of staff accepting gifts made equity with care/service providers an even greater challenge in this setting. Participants shared creative examples of input into relationship reciprocity: Sally offered recipes to the kitchen staff when she noticed their blander food going uneaten. Rose showed concern for a pregnant aide by asking the aide not to transfer her to the shower.

Participants in assisted living also supported staff by helping with other residents. They navigated friendships within the facility as well as relationship reciprocity with staff to help the facility community operate more smoothly and enhance their own relationships with fellow residents and staff. Diane watched an acquaintance walk into a room with an aide while they waited to go to dinner. She saw that the woman was about to sit down and knew how difficult it would then be to get the woman into the dining room. Diane greeted her with ‘I was just walking into dinner. Why don't we walk in together?’ She noted the aide's gratitude for her intervention. This dynamic up-played the dependency of participants' peers in the assisted living facility while highlighting participants' capacity to support staff, a power leveraging theme which played into a sense of belonging to the larger social environment.

Belonging

Community dwelling. There were two important aspects to feelings of belonging to the larger social environment for participants living in their own homes: staying informed about what was happening in the world and maintaining the cognitive ability to understand what was happening. Cognitive presence was paramount to the ability to maintain their status as functioning members of society.

This group of participants valued consuming news to stay informed about the world. They read newsletters or made donations to complement, and often replace, other interactions with groups and communities in which they had once more actively participated. Interacting in person had become more difficult or less worth the requisite intentionality, so they turned to other methods to maintain a connection to those groups and communities. Sarah, for example, had stopped attending her church's services since she stopped driving, but she still paid her membership dues. April described connecting with the world through news:

I used to be more involved. And now I'm not. I used to go to listen to more speakers and such things, which I don't do now because they're mostly in the evening. So I don't go. So I read it in the papers. There's the Jewish News. I find that in the Wall Street Journal, there's a lot of long articles, which I don't read. But I read a lot of what's going on. Here and anywhere else in the world.

Participants living in their own homes feared losing their mental faculties and thus their sense of belonging in the world. They engaged in some activities, especially solo activities, more for intellectual challenge than for entertainment. Edith worked on New York Times' crossword puzzles and invented a solo version of mah-jongg. She was grateful that she understood what was going on in the world. She explained, ‘I feel as long as I can do the New York Times crossword puzzle, I haven't lost it completely’. The desire to be one of the people who ‘still have their marbles’, as Rose said, reflected the anxieties of participants living in their own homes about appearing to themselves and others like they belonged in the world of cognitive normalcy. Edith described the value she placed on mentally belonging to the world:

I do thank God that, you know, I pretty much know what's going on in the world. When I hear the news, I know what's happening. And I may not remember names like I used to, but I have my friend who cannot remember what she did yesterday. To me, that's so sad.

This group of participants also valued physical health and strength as a symbol of independence, an indication they could still manage their lives in their own homes. Shirley explained that she was motivated to resume exercise by the prospect of being forced to move to assisted living, in which case she felt she would ‘just shrivel up and die’.

Shirley's quote sums up the anxiety of many participants living in their own homes around losing their current status in the world, whether cognitively, physically or just in their ability to keep up with everyone else who lived independently. They feared that a loss of status might land them in a place like an assisted living facility.

Assisted living. While participants in assisted living valued a sense of belonging to the larger social environment, they also emphasised how they belonged within the assisted living facility. As introduced in the relationships section, this feeling was partly fuelled by their self-perceived position as members of the resident community and as individuals transcendent to the resident community, closer to the autonomy of staff. This perceived in-between status helped these participants augment their sense of belonging to the larger social environment. Their fellow residents represented a community within the facility, offering them a sense of comfort and solidarity in their shared challenges as older adults. The staff represented the larger social environment beyond the facility and were respected as fully participating members of society in a position to care for the older, less-able bodies around them. Sally described her mixed feelings about fitting into the community of residents:

So many here have doctorates and their education … Other residents, yeah. It's amazing. I mean, they all seem to know each other, too, from years ago. It's amazing. That was a little threatening to me at first.

Participants in assisted living maintained a sense of belonging to the larger social environment by bringing in the outside world. They accomplished this by bringing in people from outside the facility, by mimicking the outside world inside the facility and by showing how living inside the facility did not sever their participation in the larger social environment.

Participants worked with the push and pull of facility barriers and opportunities to bring in the outside world. In many cases, it was more difficult to host visitors at the facility than for participants living in their own homes. Beatrice, who liked to stay up late, explained that she could not have friends over at her preferred time because visitors were not allowed to enter after the doors locked at 8:00 pm. In other cases, participants in assisted living took advantage of the facility's communal spaces and activities to portray to outsiders that the facility was not such a foreign, isolated place. Participants at Beatrice's facility frequently mentioned the cafe. These participants embraced the cafe as a way to relate to outsiders, just like going out to eat:

Like at [the cafe], they have wonderful chicken quesadillas. Try it. They're big. My grandson lives in the area. Six foot four and red hair. And I always invite him for lunch. I order a quesadilla and there's always enough for me and left over for him. So, I can always go down there. Like when my [friends] came, that's where we went. (Sally)

The lack of intra-facility visiting afforded participants a way to preserve a private space and maintain a barrier between alone time and social time. Participants living in their own homes faced barriers to achieving interaction when they sought it, but participants in assisted living utilised this private space to protect themselves against too much interaction. Without such privacy, too much interaction could erode participants' sense of agency in their social lives.

Although most participants in assisted living considered themselves members of the facility community, that community did not necessarily feel organic. Diane observed the artificiality of the facility community:

Because it's a business, as well [as] a community of people, there's a little artificiality to it being a community … They're responsible to us because of an exchange of goods, money. So, that's a very different relationship than a friendship relationship. They're very friendly. I don't mean to imply they aren't. But the fact of the matter is we pay them to be friendly.

Diane's statement suggests that participants in assisted living operated within a prescribed community. While staff and administrators cultivated a friendly and caring environment that participants appreciated, the community was not organic. Those who lived in the facility still needed to adapt their own social connectedness expectations and adjust their behaviour to reconcile any disconnectedness they felt from their pre-assisted living social connectedness expectations.

Perceived isolation

Community dwelling. Participants living in their own homes reported little perceived isolation. For the most part, the quantity and quality of social relations in their lives met their current expectations. They may have had different expectations earlier in their lives, but they had adapted their expectations as their lives changed. Most had at least a few very meaningful current relationships: adult children, a few friends, siblings or other relatives. They also had a number of less-meaningful relationships that were sufficient for their expectations. Many participants in that group reflected on their acceptance of the loss of past meaningful relationships. Susan explained her lack of motivation to replace her past significant relationships:

Actually, my sister was my best friend. She was just a year older than I. So, we were almost like twins. And I really miss her. She's gone six years. She was my best friend. A lot of my friends have died. I'm 85, so a number of them died sooner than I did. My husband was also my best friend. So, the friends I have now are pretty much just friends. Nobody really that I would say I'm close with.

Bonnie expressed a similar apathy towards cultivating new relationships:

I know how to be social. I think I'm pretty easy and friendly. I know how to keep a conversation going. And right now, I just – I'm not interested. I'm just finding that I'm not liking people that much to pursue, actively pursue.

Two participants living in their own homes did express feelings of perceived isolation. Notably, neither of these participants drove. These two participants were constrained by more factors than other participants living alone in their own homes who did not drive. One participant's cumbersome health challenges made mobility difficult. She relied mostly on her adult son and her aides for transportation. Her son had a busy schedule and she had to get rides from her aides approved in advance. The other participant had very few relationships remaining in her life. Her interactions had become extremely restricted since she stopped driving. She struggled to maintain connections with individuals, groups and communities. Both of these participants reported feeling like a bother or a nuisance when trying to initiate interactions that would require others to go out of the way to visit or drive them.

Assisted living. Participants in assisted living also reported minimal perceived isolation. This finding aligns with the theme of availability of interactions for participants in assisted living. They did not lack quantity of social relations. Although many relationships within the assisted living facilities lacked depth, their quantity sufficed expectations. This functioned in concert with the availability of some higher-quality relationships outside the facility. Beatrice described her adjusted expectations for the quality of relationships within the assisted living facility:

There's an unlimited amount of socialising one could do within the building. I have the impression people don't. Some seem to know each other well enough to see each other not at mealtimes, but most people just see each other at mealtimes, I think. And I'm not feeling any need for that. I have enough going on of my old life that I'm not feeling a need to make a whole lot of new friends or anything. I would very easily do it if I felt the need for it, but I don't.

Participants in assisted living had also lost many of their highest quality relationships to death. As with participants living in their own homes, participants in assisted living demonstrated remarkable acceptance of these losses. Margaret, for example, carved out time for herself when she felt an impending bout of grief for her husband. She allowed herself time to be sad then resumed her regular social life again.

As discussed earlier, regular social life for participants in assisted living was characterised by availability. A few participants explained their actions when they felt a need for contact. Beatrice said, ‘I still feel I have control over my life. That if I was lonely, I could just go find a friend. Just get on the phone and talk to someone.’ Arlene said, ‘All you have to do is walk out and be involved in something. I have had days when I'm just really tired, just from talking.’

This analysis began with the theme of availability and intentionality. While we initially applied this theme to interactions as tools for social connectedness, it applies to perceived isolation as well. Participants in assisted living reported minimal perceived isolation because they lacked isolation. They had constant access to people. Participants living in their own homes reported minimal perceived isolation because they did not perceive isolation. Although they may have experienced more objective isolation than participants in assisted living or other populations, their intentionality to achieve interactions translated to how they perceived their own social connectedness. They adapted their expectations to minimise the discrepancy between their actual and desired social connectedness.

Discussion

These interviews reveal important variances between the experiences of social connectedness of older women (aged 75+ years) living alone in the community and older women living in assisted living through their interactions, relationships and sense of belonging. They also show a remarkably similar lack of perceived isolation between the two groups. The key takeaway from these interviews is older women's capacity to redefine their experience of social connectedness in alignment with the interactions and relationships available to them.

Participants living in their own homes required more effort and intentionality to overcome the barriers they faced to interaction, which accords with evidence that social connections vary among older adults who age in place at home rather than in an assisted living community (Lawrence and Schille Schigelone, Reference Lawrence and Schille Schigelone2002; Isherwood et al., Reference Isherwood, King and Luszcz2017; Pirhonen et al., Reference Pirhonen, Tiilikainen and Pietila2018). In contrast, women in assisted living lived inside a framework of available interaction. Participants in assisted living focused on control and reciprocity in their relationships to residents and staff. They emphasised maintaining a degree of separation from other residents. Participants living in their own homes also emphasised control over depth and commitment in their relationships. They also worked to maintain reciprocity in different types of relationships. Gender roles and expectations about helping, nurturing and providing support (Calasanti, Reference Calasanti, Calasanti and Slevin2006; Calasanti and King, Reference Calasanti and King2007) may help explain why participants living in their own homes felt more comfortable helping dependent older adult friends than they felt accepting help when it was needed.

Women in assisted living enhanced their social connectedness by integrating interactions with their external social networks into the assisted living environment. Participants who lived in one particular facility told stories of inviting friends over to eat lunch at the cafe, having family over for dinner at the facility with old friends of theirs and inviting friends to musical programmes.

Given that social networks tend to shrink and intensify among older adults as members die or become difficult to access (Isherwood et al., Reference Isherwood, King and Luszcz2017), it is unsurprising that older women living in their own homes channelled much of their energy into maintaining current meaningful relationships rather than developing new relationships. While current meaningful relationships were particularly salient for older women living in their own homes, existing external social networks were critical for women in assisted living. This finding aligns with scholarly work finding that external social networks affect older adults' integration into internal social networks in assisted living facilities (Powers, Reference Powers1992; Rossen and Knafl, Reference Rossen and Knafl2003; Perkins et al., Reference Perkins, Ball, Kemp, Hollingsworth and Pruchno2013). The lack of barriers to interaction within the facility, in combination with the constant presence of others and structured and unstructured interactions with them, offered unlimited opportunity for women in assisted living to engage with others within the walls of the facility. Engaging the external social network usually required more intentionality.

These experiences varied with the scale and nature of each participant's challenges. One exception to these findings were women in assisted living who drove. These women described a higher quantity of meaningful relationships outside the facility than other participants in assisted living. Their experiences of social connectedness were more similar to those of participants living in their own homes than they were to the experiences of participants in assisted living. However, the experiences of participants living in their own homes who did not drive were even more distinct from both groups. In this case, the experiences of social connectedness for participants living in their own homes were characterised by an even higher degree of intentionality, as they did not experience the same accessibility of social connectedness as participants in assisted living. This finding aligns with research that driving cessation increases the odds of social isolation among older adults (Qin et al., Reference Qin, Xiang and Taylor2020) and thus may require more intentionality for social connectedness. It should also be noted that existing social networks varied between participants. For example, one of the participants who lived in her own home and did not drive also had very few existing connections, which made social interactions even harder to come by. Some participants living in assisted living had extensive local social networks which made it easier for them to feel connected outside the assisted living facility.

Experiences of social connectedness varied between participants living alone in their own homes and participants in assisted living in part because the experience of ageing for these women required different ways of defining and redefining social connectedness. Where Isherwood et al. (Reference Isherwood, King and Luszcz2017) described a shrinking, intensifying, more difficult to access social network for all older adults, and Kaufman (Reference Kaufman1990) explained the transition to redefining one's self-concept as older adults begin to receive care at home, the participants living in their own homes in our study described a process of approaching their newfound barriers to interaction with intentionality. Participants in assisted living, in contrast, redefined their entire social world. The facility community represented the rest of society. It was something to belong to, yet also a space to redefine themselves as individuals amongst a homogenous population. They merged their internal and external social worlds by inviting others in and making the inside feel like the outside.

The lack of perceived isolation reported by both groups reflected Cornwell and Waite's (Reference Cornwell and Waite2009) finding that older adults tend to counteract risk factors for perceived isolation (transportation and mobility limitations, loss of social network members) by optimising their available social resources and adjusting their expectations of connectedness. Adjusted expectations were a key theme in the interviews. Although participants often acknowledged feelings of loneliness when thinking about the loss of loved ones, they adapted to this new normal. They sat with their grief as it came to them and accepted that their current selves had different standards for what social connectedness meant to them.

The two participants who did express feelings of perceived isolation aligned with Cornwell and Waite's (Reference Cornwell and Waite2009) findings that perceived isolation is associated with smaller social networks and less-frequent participation in social groups. While most participants living in their own homes experienced these factors, these two participants struggled more than the others to overcome barriers to interaction. Therefore, they perceived a higher discrepancy between their actual and desired connectedness.

The surprising similarity between the groups living in assisted living and their own homes in their experience of perceived isolation underscores the significance of this study as one that brings into the conversation two distinct areas of gerontology research: ageing in place and ageing in senior living facilities. We argue that the social experience in old age appears distinct between assisted living and ageing in place literature because the social experience is primarily about ageing individuals defining and redefining social connectedness for themselves. Although perceived isolation is difficult to evaluate from an objective perspective, it is nonetheless significant to the understanding of social experiences from the point of view of the population of interest. Especially in the case of a population such as older adults, who are believed to be at greater risk of isolation and loneliness, it is important for researchers to take individual, subjective experiences into account (Settersten and Thogmartin, Reference Settersten and Thogmartin2018) to understand how circumstances affect individuals' evaluation of their lives and how this evaluation affects their approach to managing their social connectedness.

These findings pose a few challenges and opportunities for senior housing service providers that have research and practice implications, including how assisted living facilities can provide tools for older women to maximise their social connectedness experience in a way that matches their expectations. Additionally, this research underscores the need for service providers to minimise barriers to interaction that reduce the discrepancy between desired and actual social connectedness. One option is to approach assisted living facilities with an emphasis on factors that pull the general community into the assisted living community as opposed to pushing residents who live there away from the larger social environment. Assisted living facilities should consider how they can develop spaces and programmes that normalise the facility as a place for older adults living in their own homes to interact. Additionally, they should expand the appeal of their space to members of the external social networks of people who live in their facilities. This approach could support the interactions of older adults living in assisted living facilities with their external social networks, provide a space for older adults living in their own homes to access a framework of available interaction and smooth potential future transitions from living in one's own home to an assisted living facility.

Future research could expand on how physical spaces, such as lounges or dining halls, can facilitate relationships within the facility and invite in already-important relationships to interact within the facility. There is also much to learn about how facility policies, such as mealtime seating arrangements or visiting hours, facilitate new relationships within the facility and with guests.

While this study provides important insights for practitioners and scholars, the findings are limited due to the size of the sample and its relatively homogeneity. This study did not collect data about participants' education levels or socio-economic status, which may have influenced their experiences. Most lived in a suburban area or near a small town. The sample was predominantly white. Future research is needed that further examines a more diverse range of experiences. In addition, this in-depth examination was limited in scope to individual experiences; we did not engage in facility-level data collection that would illuminate how facility structures and environments may impact an older adult's experience of social connectedness while living in the facility. Future research that includes this mezzo-level data would shed more light on social connectedness in assisted living facilities. Also, future research comparing social connectedness between older men and women in this age group may shed light on potential gender differences here, including how older adults are influenced by expectations surrounding gender roles and care-giving and care-receiving. While this study recruited through people who knew potential participants, future research should minimise biased recruitment through gatekeepers. The scope of this study also limited the possibility to look separately at older women who do and do not drive. Future research should sample for populations entirely of older adults who do or do not drive to eliminate this factor that heavily influences how older adults experience social connectedness.

This research has important implications for practitioners, researchers and policy makers, given its findings on the subjective experiences of social connectedness and perceived isolation among a difficult-to-access population. Older women remain an understudied group, and research with women in the middle-old and oldest-old age ranges is even more sparse. Our findings on their experiences and perceptions of social connectedness and perceived isolation underscore the need for nuanced evaluations, assessments and support from clinicians that address their unique needs. This research further illuminates how the needs of older women in assisted living and in the community may differ and thus how practitioners can tailor interventions and services to meet these needs. COVID-19 has exacerbated perceived isolation while stressing the importance of social connectedness. During the pandemic, older adults reported greater loneliness (van Tilburg et al., Reference van Tilburg, Steinmetz, Stolte, van der Roest and de Vries2021), which was moderated by the perceived strength of relationships (Krendl and Perry, Reference Krendl and Perry2021). While our research was conducted prior to COVID-19, its findings are even more salient in a COVID-19 and post-COVID era. Ultimately, this research provides new empirical evidence about the experiences of older women regarding perceived isolation and social connectedness; it can inform researchers, practitioners, policy analysts, urban designers, and formal or informal care-givers as they explore how to shape environments conducive to social connectedness in the face of isolating limitations.

Conclusion

A constant theme in this analysis of the social experience of older women is the capacity and motivation to redefine one's expectations of social connectedness in terms of quality and quantity in response to changing factors, including availability of the social network, mobility limitations and, especially, living environment. This theme was salient in the comparison between older women living alone in private homes and those living in assisted living facilities.

Social connectedness for women living alone in private homes was defined by intentionality, by the strategic and targeted effort to navigate new types of relationships (particularly as care recipients) and imbalanced relationship reciprocity. These women showed a preference for investing their energy in the quality of fewer relationships than the quantity of more casual relationships, whereas the experience of women in assisted living facilities was defined by the availability of interactions. The term ‘interactions’ is significant because the high quantity of interactions superseded the significance of the quality of relationships within the internal social network. This tendency to redefine social connectedness expectations gave context to the remarkably similar lack of perceived isolation between the two groups. As many of the women adjusted to changing and newly limiting factors in their lives, they redefined their social connectedness expectations to protect themselves from the discomfort of falling short of their own earlier expectations.

This redefining of expectations and lack of perceived isolation does not negate that participants maximised their tools for social connectedness. Their savvy conduct to leverage power and control, maintain relationship reciprocity and mimic the external social world inside assisted living facilities highlights the need for future research and interventions in fields outside gerontology. Transportation, urban design and architecture could address issues that arose around driving and the separation of social entities. Future research and practice should address why cessation of driving is such an extreme blow to the social experience and living in senior housing such a segregation from the larger social environment.

This study exemplifies the capacity for older women to redefine their social connectedness expectations. It also highlights an opportunity for cross-disciplinary action to integrate housing, social and need-based entities in addition to improving transportation options so that cessation of driving or need for instrumental support does not stunt social connectedness in a society that is most inclusive to the young and able-bodied.

Acknowledgements

Our sincere thanks and gratitude to the women who shared their stories with us, the community leaders, assisted living staff and many more who connected us with participants, and to Dr Karin Martin for her invaluable insight on the design and analysis of this project.

Financial support

This work was supported by the University of Michigan Department of Sociology and Honors College.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

This study received Institutional Review Board exemption (HUM00144950).