Introduction

Promoting employment and social participation amongst older people is the dominant reaction to population ageing both in the academic sphere and in social policies. A higher level of productive social roles consisting of regular activities in later life is usually presented as a generally beneficial solution to challenges connected with population ageing (overload of social and health systems, poor health and lower quality of life (QoL)). Moreover, these challenges would be addressed to both older adults in the form of personal conditions improvement and society through more paid and unpaid work being done (Walker and Maltby, Reference Walker and Maltby2012; Timonen, Reference Timonen2016; Marsillas et al., Reference Marsillas, De Donder, Kardol, van Regenmortel, Dury, Brosens, Smetcoren, Braña and Varela2017). Participation in society in later life is beneficial to older people themselves. For older people, social participation has an enhancing effect on their physical health (Thomas, Reference Thomas2011, Reference Thomas2012), mental health (Engelhardt et al., Reference Engelhardt, Buber, Skirbekk and Prskawetz2010; Olesen and Berry, Reference Olesen and Berry2011) and life satisfaction (Gergen and Gergen, Reference Gergen, Gergen, Worell and Goodheart2006; Adams et al., Reference Adams, Leibbrandt and Moon2011; Potočnik and Sonnentag, Reference Potočnik and Sonnentag2013), mitigating also the intergenerational conflict in a society (Hess et al., Reference Hess, Nauman and Steinkopf2017).

The notion of activities as a way to make population ageing sustainable and even beneficial has been the main assumption of the ‘activity theory’ (Havighurst, Reference Havighurst1961) and the concept of active ageing (Walker, Reference Walker2002). Since the active ageing approach has been built on the assumptions of the activity theory and both approaches expect prevalently positive outcomes of activities in later life, this study tests the assumptions of both approaches whilst referring mostly to the more recent and influential active ageing approach. In large part, the concept of active ageing was developed by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2002) and the European Union (EU) (Commission of the European Communities, 2002). Whilst the active ageing approach has been dominating the European and other geographical contexts, a similar meaning is connected to successful ageing influential in the United States of America, which also aims for more healthy and engaged later life through high social activity (Havighurst, Reference Havighurst1961; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Ajrouch and Hillcoat-Nallétamby2010; Rowe and Kahn, Reference Rowe and Kahn2015).

The paper mainly aims to assess the impact on the subjective QoL of activities supported by the active ageing approach while controlling for other roles and external conditions. The analysis of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) follows changes in employment, social participation, physical activities and care-giving over time and their effect on the QoL whilst controlling for each other. In this way, the study identifies the independent utility of the activities for older adults’ QoL controlling for other activities in the same models.

Activities supported by the active ageing approach and their expected outcomes

Activities encompassed by active ageing differ by the information source, but the EU mainly supports prolonged employment, participation in society and independent living. The category ‘participation in society’ includes care-giving, volunteering, lifelong learning and political activities (EU Council, 2012; Eurostat, 2012). This diverse list of activities is connected by their presumed utility for both individuals (Walker, Reference Walker2009; Adams et al., Reference Adams, Leibbrandt and Moon2011; European Commission, 2013; Marsillas et al., Reference Marsillas, De Donder, Kardol, van Regenmortel, Dury, Brosens, Smetcoren, Braña and Varela2017) and society (EU Council, 2012; European Commission, 2013; Foster and Walker, Reference Foster and Walker2015). This study tests their utility, which is not supported conclusively because specific activities have different consequences for the QoL in different economic, institutional and cultural contexts (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Leibbrandt and Moon2011; Neuberger and Haberkern, Reference Neuberger and Haberkern2014; Di Novi et al., Reference Di Novi, Jacobs and Migheli2015; Lakomý, Reference Lakomý2019).

The EU vigorously supports active ageing policies, which have resulted in thousands of events and programmes at all geographical levels of the European continent. The development of the Active Ageing Index (AAI) as a multi-dimensional operationalisation measuring active ageing across countries was amongst the most ambitious and influential projects implementing active ageing (European Commission, 2013; Sidorenko and Zaidi, Reference Sidorenko and Zaidi2013; Vidovićová, Reference Vidovićová, Zaidi, Harper, Howse, Lamura and Perek-Białas2018). The values of the AAI for each country and region are published every two years in order to indicate ‘the untapped potential of older people for more active participation in economic and social life’ (Zaidi et al., Reference Zaidi, Harper, Howse, Lamura, Perek-Białas, Zaidi, Harper, Howse, Lamura and Perek-Białas2018a: 3). Importantly, the large-scale AAI project suggests the following two points. Firstly, all targeted activities are intended to spread over time with individuals expected to perform as many roles as possible. Secondly, no cultural, institutional or economic differences within the EU are sufficiently considered by the uniform set of supported activities.

QoL is a key outcome of this study because its improvement in older adults – besides the improvement of health and independence – is the central goal of active ageing, as well as of other approaches focused on the older population (Walker, Reference Walker and Walker2004; Paúl et al., Reference Paúl, Ribeiro and Teixeira2012; United Nations, 2013; Marsillas et al., Reference Marsillas, De Donder, Kardol, van Regenmortel, Dury, Brosens, Smetcoren, Braña and Varela2017). The concept of QoL is a complex research phenomenon due to its amorphous and multi-dimensional nature, which is reflected differently by several competing paradigms (Walker, Reference Walker2005). This study uses the CASP scale as the theoretically and empirically grounded measurement of subjective QoL in later life, which is further discussed in the methodological section.

Some proponents of active ageing present empirical evidence on the benefits of roles supported by active ageing to QoL (Reichert and Weidekamp-Maicher, Reference Reichert, Weidekamp-Maicher and Walker2004; Walker, Reference Walker2005; Katz, Reference Katz2009; Marsillas et al., Reference Marsillas, De Donder, Kardol, van Regenmortel, Dury, Brosens, Smetcoren, Braña and Varela2017), but this empirical evidence usually comes from the most prosperous countries and is obtained from cross-sectional data. Moreover, the effect of various roles differs (Siegrist and Wahrendorf, Reference Siegrist and Wahrendorf2009; Potočnik and Sonnentag, Reference Potočnik and Sonnentag2013), with identical roles having various outcomes across macro-contexts (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Leibbrandt and Moon2011; Neuberger and Haberkern, Reference Neuberger and Haberkern2014; Di Novi et al., Reference Di Novi, Jacobs and Migheli2015), which should also appear in the region-specific models including all important activities.

Theoretical approaches applied to activity outcomes

The proponents of active ageing aim for an increasing prevalence of all activities and expect the effect of activities on QoL to be positive regardless of other factors (Walker, Reference Walker2009; United Nations Economic Commission for Europe and European Commission, 2015; Zaidi et al., Reference Zaidi, Gasior, Zolyomi, Schmidt, Rodrigues and Marin2017; Varlamova, Reference Varlamova2018). However, an increasing amount of empirical findings show that the outcomes of each activity in older ages depend on its content and micro/macro-context (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Leibbrandt and Moon2011; Di Gessa and Grundy, Reference Di Gessa and Grundy2013; Neuberger and Haberkern, Reference Neuberger and Haberkern2014; Lakomý, Reference Lakomý2019, Reference Lakomý2020). The outcomes of activities varying from positive to negative are expected by neither the active ageing approach nor the activity theory. However, more recent adjustments to the active ageing approach and activity theory claim that only personally meaningful and freely chosen activities improve QoL in later life (Musick and Wilson, Reference Musick and Wilson2003; Rozanova et al., Reference Rozanova, Keating and Eales2012; Foster and Walker, Reference Foster and Walker2015). This revised version of the whole activity approach makes it possible to expect varying outcomes of activities although many publications, and especially policy tools, do not take this revision into account (Timonen, Reference Timonen2016; Marsillas et al., Reference Marsillas, De Donder, Kardol, van Regenmortel, Dury, Brosens, Smetcoren, Braña and Varela2017; Zaidi et al., Reference Zaidi, Harper, Howse, Lamura and Perek-Białas2018b).

The active ageing approach and activity theory are based on a set of role theories (George, Reference George1993). The theory of role accumulation expecting beneficial outcomes of additional roles (Sieber, Reference Sieber1974), the theory of role strain expecting harmful outcomes (Goode, Reference Goode1960), the continuity theory (Atchley, Reference Atchley1989), etc. These approaches assume that individual identities are developed and maintained through social roles. Based on this point of departure, the activity theory assumes that older adults need to maximise their activities – especially after the retirement exit – in order to maintain the sense of identity through performance of (meaningful) roles (Havighurst, Reference Havighurst1961; Nimrod, Reference Nimrod2007). Hence, especially roles in the area of part-time/flexible jobs, care-giving and social participation (such as volunteering) are stressed to bring the potential to enhance identity and improve the QoL, if they are normatively supported (Neuberger and Haberkern, Reference Neuberger and Haberkern2014; Di Novi et al., Reference Di Novi, Jacobs and Migheli2015) and individually meaningful (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Leibbrandt and Moon2011; Rozanova et al., Reference Rozanova, Keating and Eales2012).

In contrast to the role approaches, social identity theory, rather than the importance of relatively stable roles and role expectations for individual identity, stresses the more-flexible group memberships (Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979; Hornsey, Reference Hornsey2008: 210). Categorisation through social participation into groups enables an improvement of self-concept – and ultimately of subjective QoL – through comparison to other groups, such as older people not performing the activity. Moreover, social categorisation into social groups alters the choice of other activities and overall outcomes of any roles, as ‘the norms of relevant ingroups are a crucial source of information about appropriate ways to think, feel, and act’ (Hornsey, Reference Hornsey2008). Nevertheless, the assumption of these mechanisms is an adequate salience of a given group, which may be not fulfilled by occasionally visiting a sports club or third-age university. Generally, the social identity theory would assume that it is particularly activities within positively evaluated social groups that improve the QoL of older adults. Furthermore, this approach can account for the variation of outcomes both within and amongst countries and welfare states due to emphasising the normativity of cognition and behaviour based on group values (Hornsey, Reference Hornsey2008; Hogg, Reference Hogg, McKeown, Haji and Ferguson2016).

Empirical evidence on the effects of activities and their interdependencies

The roles in later life are interdependent because both conflicts (Goode, Reference Goode1960) and complementarities (Sieber, Reference Sieber1974) amongst roles are the usual phenomena. Furthermore, group membership and connected social norms also vary in their salience (Hornsey, Reference Hornsey2008; Sets and Burke, Reference Sets and Burke2010). A change in one role can affect the outcome of others; thus, all key roles in later life should be contained in the same model when their impact on QoL is evaluated.

The existing research suffers from several gaps stemming from the issues discussed above. Firstly, many papers have examined the effect of employment/retirement (Latif, Reference Latif2011; Di Gessa and Grundy, Reference Di Gessa and Grundy2013; Horner, Reference Horner2014), provision of care (Colombo et al., Reference Colombo, Llena-Nozal, Mercier and Tjadens2011; Broese van Groenou et al., Reference Broese van Groenou, de Boer and Iedema2013) and activities of social participation (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Leibbrandt and Moon2011; Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, Hogg and Hardill2011) on QoL. This common research design examining the effect of one type of activity ignores their interconnections. Secondly, some research controlled the labour force participation, whilst evaluating the effect of care-giving on QoL (Neuberger and Haberkern, Reference Neuberger and Haberkern2014; Di Novi et al., Reference Di Novi, Jacobs and Migheli2015; Lakomý, Reference Lakomý2020). Nevertheless, these studies still do not cover many key activities, and use only cross-sectional data. Thirdly, some authors studied the dependencies amongst different activities in older ages, but did not analyse their effect on any outcome (Burr et al., Reference Burr, Choi, Mutchler and Caro2005, Reference Burr, Mutchler and Caro2007; Arpino and Bordone, Reference Arpino and Bordone2017, Reference Arpino, Bordone, Zaidi, Harper, Howse, Lamura and Perek-Białas2018).

Arpino and Bordone (Reference Arpino and Bordone2017) argue that competition amongst activities should be reflected by active ageing approach. However, only the study of Potočnik and Sonnentag (Reference Potočnik and Sonnentag2013) not following changes over time has included all the main types of activities in later life in one model, which this paper aims to address. Hence, the paper expands the existing body of literature by (a) reflecting various outcomes of activities under different societal settings, (b) controlling for other activities, and (c) utilising the possibilities of the cross-national panel data.

The effects of activities and their variation across social contexts

The role outcomes may depend not only on the characteristics of an individual or on their compatibility with other roles, but also on the context connected to the prevalence, meaning, form and tradition of specific activities (Pines et al., Reference Pines, Neal, Hammer and Icekson2011; Rozanova et al., Reference Rozanova, Keating and Eales2012; Timonen, Reference Timonen2016; de São José et al., Reference De São José, Timonen, Amado and Santos2017). The economic, institutional and cultural conditions in a given country shape the outcomes of different activities to various degrees and the next paragraphs aim to identify the essential macro-factors for each type of activity available in the literature.

Labour force participation as a role highly emphasised by active ageing policies (Foster and Walker, Reference Foster and Walker2015; Madero-Cabib and Kaeser, Reference Madero-Cabib and Kaeser2016) seems more beneficial in less-wealthy countries as a way to maintain living standards (Borges Neves et al., Reference Borges Neves, Barbosa, Matos, Rodrigues, Machado, Börsch-Supan, Brandt, Litwin and Weber2013; Hofäcker, Reference Hofäcker2015; Lakomý, Reference Lakomý2019). The level of labour force participation in later life in a country is shaped by the statutory retirement age, which does not vary much across European countries (Trading Economics, 2017), with this variation being mostly explained by the varying life expectancy (Salomon et al., Reference Salomon, Wang, Freeman, Vos, Flaxman, Lopez and Murray2012). This activity has positive effects for older adults according to some studies (Daatland et al., Reference Daatland, Veenstra and Lima2010; Di Gessa and Grundy, Reference Di Gessa and Grundy2013), whilst other found negative (Latif, Reference Latif2011; Horner, Reference Horner2014; Gorry et al., Reference Gorry, Gorry and Slavov2015) or context-dependent effects (Borges Neves et al., Reference Borges Neves, Barbosa, Matos, Rodrigues, Machado, Börsch-Supan, Brandt, Litwin and Weber2013; Lakomý, Reference Lakomý2019) of working longer. Regarding the contextual variation, Borges Neves et al. (Reference Borges Neves, Barbosa, Matos, Rodrigues, Machado, Börsch-Supan, Brandt, Litwin and Weber2013) find that active employment reduces depression of older adults in countries of southern and central Europe as opposed to western and northern Europe. Similarly, Lakomý (Reference Lakomý2019) indicated the positive effect of labour force participation in southern and post-communist Europe and the negative effect in northern and western Europe, with the pension adequacy as the most suitable explanation of these regional differences.

The previous research has found a rather positive effect of less-intensive (Potočnik and Sonnentag, Reference Potočnik and Sonnentag2013; Lakomý, Reference Lakomý2020) and negative effect of more-intensive and personal care-giving (Colombo et al., Reference Colombo, Llena-Nozal, Mercier and Tjadens2011; Broese van Groenou et al., Reference Broese van Groenou, de Boer and Iedema2013; Kaschowitz and Brandt, Reference Kaschowitz and Brandt2017) and this paper keeps the distinction. The provision of care can be more beneficial in countries with stronger familial norms (Neuberger and Haberkern, Reference Neuberger and Haberkern2014; Di Novi et al., Reference Di Novi, Jacobs and Migheli2015). This difference seems attributable to the concept of structured ambivalence. The structured ambivalence, inspired by the concept of sociological ambivalence (Merton, Reference Merton1976) and coined by Connidis and McMullin (Reference Connidis and McMullin2002a, Reference Connidis and McMullin2002b), expects that roles fitting the social norms lead to subjective outcomes better than those of non-fulfilment of normative expectations. Therefore, various types of care-giving are more beneficial in macro-contexts more appreciating the role of the care-giver and punishing its avoidance via stronger familial norms (Neuberger and Haberkern, Reference Neuberger and Haberkern2014). Moreover, care-giving can be more beneficial in countries where formal care is more available, which makes informal care-giving less focused on intensive personal care dictated by circumstances. Formal care seems especially important in splitting the responsibilities for a dependent older relative with family (Daatland and Lowenstein, Reference Daatland and Lowenstein2005; Brandt et al., Reference Brandt, Haberkern and Szydlik2009; Lakomý, Reference Lakomý2020). The paper by Di Novi et al. (Reference Di Novi, Jacobs and Migheli2015) is a rare example of a detailed study on the contextual variation of care-giving outcomes, which found a beneficial effect of care provision on subjective QoL in southern Europe (normative appreciation), detrimental effect in continental Europe (lower normative support and lower availability of formal care) and no effect in northern Europe (lower normative support and higher formal care availability).

The effect of social participation is – compared to the ambiguous effect of caregiving and labour force participation – generally positive (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Leibbrandt and Moon2011; Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, Hogg and Hardill2011; Potočnik and Sonnentag, Reference Potočnik and Sonnentag2013). Social participation is the group encompassing the rest of the activities studied although physical activity or volunteering do not necessarily have the social dimension. The social participation is usually supported by civic norms in society (Curtis et al., Reference Curtis, Baer and Grabb2001; Hank, Reference Hank2011; Wiertz and Lim, Reference Wiertz and Lim2019), which stem from the cultural, political and religious tradition of a given society (Hank, Reference Hank2011), and is higher in more-developed countries and more-stable democratic regimes (Curtis et al., Reference Curtis, Baer and Grabb2001; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Oser and Marien2016; Nikolova et al., Reference Nikolova, Roman and Zimmermann2017). The concept of structured ambivalence applied to social participation would mean that the activities of social participation have a more-positive effect in more-developed civic societies, in which they are more appreciated.

Hypotheses and their justification

Addressing all the main roles and other characteristics within an individual in panel data, this paper hypothesises:

• Hypothesis 1: The effect of labour force participation on subjective QoL is negligible.

• Hypothesis 2: The effect of care-giving outside the household on subjective QoL is positive.

• Hypothesis 3: The effect of care-giving within the household on subjective QoL is negative.

• Hypothesis 4: The effect of activities usually performed in groups and designated as social participation on subjective QoL is positive.

Most importantly, the variation across contexts is expected for all overall effects:

• Hypothesis 5: The effect of labour force participation on subjective QoL is more positive in less-prosperous regions.

• Hypothesis 6: The effect of care-giving outside the household on subjective QoL is more beneficial in regions with stronger familial norms.

• Hypothesis 7: The effect of care-giving within the household on subjective QoL is more beneficial in regions with higher accessibility of formal care.

• Hypothesis 8: Types of social participation have a more-positive effect on subjective QoL in regions with stronger civic norms.

Hypotheses 1–4 address the overall effects of activities and stem primarily from the cited empirical evidence. The activity theory would assume positive effects of all (at least all meaningful) activities (Havighurst, Reference Havighurst1961; Adams et al., Reference Adams, Leibbrandt and Moon2011), whilst the social identity theory expects beneficial outcomes of activities within positively evaluated social groups (Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979; Hornsey, Reference Hornsey2008), which contains social participation and, to some extent, labour force participation as well. Hypothesis 5 is based on the assumption of more beneficial labour force participation in less-wealthy countries as a way to maintain the living standard in later life (Borges Neves et al., Reference Borges Neves, Barbosa, Matos, Rodrigues, Machado, Börsch-Supan, Brandt, Litwin and Weber2013; Hofäcker, Reference Hofäcker2015; Lakomý, Reference Lakomý2019). Hypothesis 6 follows the logic of structured ambivalence (Connidis and McMullin, Reference Connidis and McMullin2002b; Neuberger and Haberkern, Reference Neuberger and Haberkern2014), expecting the care-giving outside the household to be more beneficial in regions with a higher social appreciation of this activity. In contrast, the care-giving within the household is expected to be more beneficial in the conditions of more-accessible formal care (Hypothesis 7), with the responsibilities for a dependent older relative shared by the family (Daatland and Lowenstein, Reference Daatland and Lowenstein2005; Brandt et al., Reference Brandt, Haberkern and Szydlik2009; Lakomý, Reference Lakomý2020). Finally, Hypothesis 8 also uses the argument of structured ambivalence, but this time for social participation and its higher appreciation in the conditions of stronger civic norms (Curtis et al., Reference Curtis, Baer and Grabb2001; Hank, Reference Hank2011; Wiertz and Lim, Reference Wiertz and Lim2019).

Data, methods and variables

Data and sample

This study uses data from the SHARE project, which is a large European project in which respondents from nationally representative samples of the population over 50 years and their spouses are interviewed every two years (Börsch-Supan et al., Reference Börsch-Supan, Brandt, Hunkler, Kneip, Korbmacher, Malter, Schaan, Stuck and Zuber2013; Börsch-Supan, Reference Börsch-Supan2017). The SHARE data from Waves 4, 5 and 6 provide recent information from three time-points in a medium timespan, which capitalise on the panel dimension of the data and provide enough within-person variation to control for unobserved heterogeneity. Furthermore, more countries participated in these subsequent waves than in the previous ones. The selected analytical approach uses only observations present in all waves of measurement, and thus it would be problematic to use more than three consecutive waves due to a low number of countries and respondents participating continually over a longer time. Finally, each of the waves misses some countries participating in SHARE, which disqualifies these countries for the analysis.

The countries listed in the study are categorised by their welfare regimes as defined by Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) and other scholars developing this typology (Ferrera, Reference Ferrera1996; Fenger, Reference Fenger2007; Ebbinghaus, Reference Ebbinghaus2012) into four European regions. The welfare regimes typology is often used in social sciences research (Ebbinghaus, Reference Ebbinghaus2012; Kammer et al., Reference Kammer, Niehues and Peichl2012; Hansen and Slagsvold, Reference Hansen and Slagsvold2016; Sirovátka et al., Reference Sirovátka, Guzi and Saxonberg2019) for reasons similar to this study. The paper finds this typology very useful due to its grouping of countries similar in welfare politics, geographic location, economic, institutional and cultural settings, the prevalence of activities, the average level of QoL and other vital macro-factors (Walker, Reference Walker and Walker2004; Eikemo et al., Reference Eikemo, Bambra, Judge and Ringdal2008; Borges Neves et al., Reference Borges Neves, Barbosa, Matos, Rodrigues, Machado, Börsch-Supan, Brandt, Litwin and Weber2013; Di Novi et al., Reference Di Novi, Jacobs and Migheli2015; Sirovátka et al., Reference Sirovátka, Guzi and Saxonberg2019). Hence, the typology is used for identifying groups of countries rather than for examining the effect of the welfare state as such. The final sample consists of data from 11 EU countries divided in line with the welfare regimes typology (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990) into social-democratic countries (Denmark and Sweden), conservative countries (Austria, Belgium, France and Germany), Mediterranean countries (Italy and Spain) and post-communist countries (Czech Republic, Estonia and Slovenia) for the more context-specific part of the analysis.

This study covers respondents aged 51–86 in Wave 4 of 2011 (age range 55–90 in Wave 6 of 2015), because active ageing addresses the chronological age as a flexible characteristic and directs its policies at all groups of older adults (Timonen, Reference Timonen2016; de São José et al., Reference De São José, Timonen, Amado and Santos2017; Zaidi and Howse, Reference Zaidi and Howse2017). The respondents aged 90+ in Wave 6 (about 2%) were dropped in order to prevent any distortion of the results by outliers with different characteristics and living conditions. The panel attrition in the sample was 32.2 per cent between Waves 4 and 5 and 23.8 per cent between Waves 5 and 6. A total of 28,283 respondents met the age definition and participated in all three waves, including 11,191 respondents not asked questions about care-giving in Waves 4 or 5 (being not family respondents) and 3,567 had at least one more missing value. Hence, the final balanced sample consists of 13,525 individuals present in all three waves. Although the drop in the number of respondents who were not family respondents may seem large, this step ensures that people living with a partner are not overrepresented, and only one member of every household is present in the final sample. The sensitivity analyses revealed that changes in the definition of the sample or the way of dealing with the missing values do not substantially alter the findings.

The baseline characteristics of the panel sample are displayed in Table 1. The table contains descriptive statistics of the whole sample, but also of the four European regions separately, as this grouping is used in the analysis. On the whole, some activities are more prevalent amongst older adults – labour force participation, care provided outside households and physical activity – whilst care-giving within the household, educational courses and participation in political organisations are rare. Regarding regional differences, all activities except for care-giving within households are most prevalent in social-democratic countries (levelling conservative countries in volunteering and political participation), whilst the opposite is true for Mediterranean countries. Conservative and post-communist welfare states fall in between, with most of the activities being carried out more often in conservative countries. The regions are similarly ordered in other individual characteristics, with social-democratic countries having higher mean age, higher level of education, QoL, better health and better financial situation. Mediterranean countries and post-communist countries can be found at the opposite end of the spectrum.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the baseline characteristics of 13,525 respondents available for analysis in the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), Waves 4, 5 and 6, sorted by welfare regime

Notes: The group of social-democratic countries consists of Denmark and Sweden, conservative countries consists of Austria, Belgium, France and Germany, Mediterranean countries consists of Italy and Spain and post-communist countries consists of the Czech Republic, Estonia and Slovenia. ISCED: International Standard Classification of Education.

Source: SHARE, Waves 4, 5 and 6, author's calculations.

Method

The analysis uses panel data from three waves of SHARE with the continuous outcome variable. The methodological approach capitalises on combining the selection into specific activities and the consequences for QoL over time. All models use the enter (not stepwise) method with inserting all variables simultaneously. The data structure has two levels – observations in time nested in the individual – and some parts of the analysis are also sorted by the European region. An alternative approach could be adding a third level of the multilevel data structure in the form of country, but 11 countries do not suffice for this step (Bryan and Jenkins, Reference Bryan and Jenkins2016). The hypothesised effects can be estimated through random- or fixed-effects regression in the two-level data structure, which are the two approaches compared in the analysis. The random-effects regression works on the same principle as the ordinary least squares regression and usually produces very similar results, whilst it is adjusted to the panel data structure and aims to model change over time. This technique uses both between-person and within-person variations, treating unobserved differences as random, which leads to higher efficiency at the expense of higher risk of bias (Allison, Reference Allison2009).

In contrast, the fixed-effects regression uses only the within-person variation to estimate the coefficients (Allison, Reference Allison2009). This procedure makes it possible to use every individual as their control, and thus it controls all stable (un)observable macro- and micro-characteristics. This robustness of the method is conditioned by a sufficient variation of predictors and their sufficient exogeneity (Windmeijer, Reference Windmeijer2000). A difference in coefficients between the random-effects model (REM) and fixed-effects model (FEM) indicates spurious effects in REM, whilst much higher standard errors in FEM result in a low efficiency of FEM estimation (Allison, Reference Allison2009). The estimation of both models on the whole sample is, therefore, compared using the Hausman test, and the more-appropriate model in terms of efficiency and bias is used for the analysis of sub-groups, which is an approach similar to the one used by Kaschowitz and Brandt (Reference Kaschowitz and Brandt2017) in the study of health effects of informal care-giving for older adults across Europe.

The fixed-effects regression is effective in some threats to causal inference such as selection and endogeneity bias (Allison, Reference Allison2009; Hanchane and Mostafa, Reference Hanchane and Mostafa2012; Brüderl and Ludwig, Reference Brüderl, Ludwig, Best and Wolf2015). Still, it does not solve all aspects of endogeneity, including those related to time-invariant predictors (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Cohen, West and Aiken2003; Allison, Reference Allison2005). Hence, the one time-variant predictor (health) is not included in FEM due to the risk of endogeneity confirmed by the Hausman test of endogeneity, with the all-time invariant predictors being excluded from FEM as well. The problem of endogeneity also relates to the assumption of temporal homogeneity, which can be relaxed if control groups and time dummies are included in the analysis (Brüderl and Ludwig, Reference Brüderl, Ludwig, Best and Wolf2015). Regarding the alternatives, the random-effect-within-between model provides more analytical options at the expense of a higher risk of bias connected to the normality assumption (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Fairbrother and Jones2019), but these are not needed in the presented analysis. Therefore, a fixed-effects regression is used by this research as superior for evaluating causal effects in this specific design (Gunasekara et al., Reference Gunasekara, Richardson, Carter and Blakely2014; Brüderl and Ludwig, Reference Brüderl, Ludwig, Best and Wolf2015; Bell et al., Reference Bell, Fairbrother and Jones2019), whilst the results should be replicated by alternative techniques in future research.

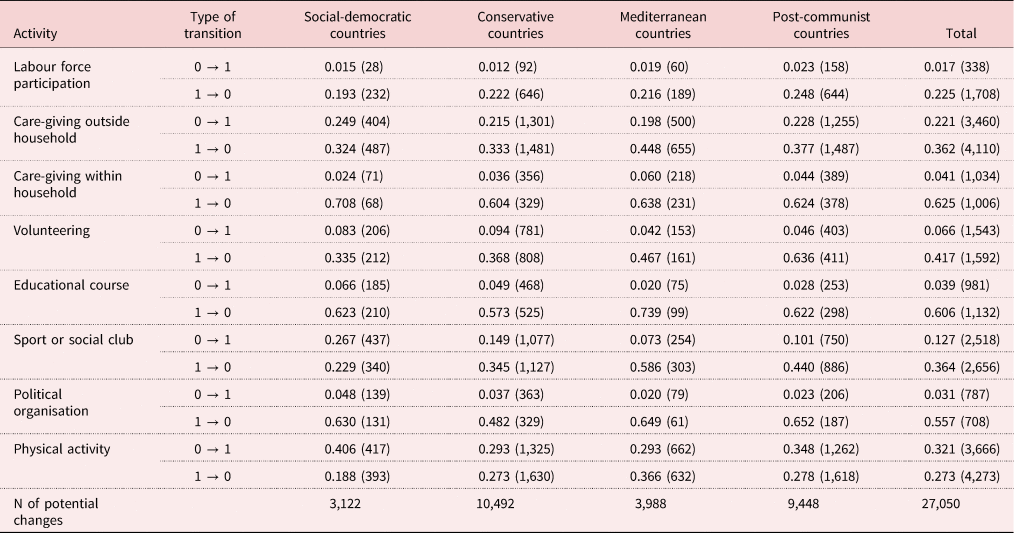

Regarding the data structure, the paper uses balanced data with respondents having fewer than three observations in the time being dropped. Table 2 shows two types of predicted probabilities – the probability to end and probability to start a given activity – with the absolute frequency of these transitions in parentheses. These data illustrate that transition from most of the activities is much more probable than transition into activities, but the frequencies of starting and ending particular activities do not differ substantially (except for labour force participation). Computing two types of transformation for each activity would give a total number of changes important for the feasibility of FEM, which use only within-person variation. This indicator shows enough changes of explanatory variables between two consecutive waves for each European region; the lowest number of changes is for care-giving within the household in social-democratic countries and participation in a political organisation in Mediterranean countries (139 and 140 changes, respectively).

Table 2. Transition probabilities of activities (and number of changes in parentheses) between two consecutive waves for 27,050 possible changes in time

Note: The group of social-democratic countries consists of Denmark and Sweden, conservative countries consists of Austria, Belgium, France and Germany, Mediterranean countries consists of Italy and Spain and post-communist countries consists of the Czech Republic, Estonia and Slovenia.

Source: Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), Waves 4, 5 and 6, author's calculations.

Dependent variable

QoL has been conceptualised and measured in many ways concerning societal, individual or both types of influences. This paper examines the theoretically grounded and empirically tested CASP-12 scale (Higgs et al., Reference Higgs, Hyde, Wiggins and Blane2003; Hyde et al., Reference Hyde, Wiggins, Higgs and Blane2003), which was designed as opposed to the practice of measuring QoL in older ages by health or longevity. CASP is based on four ontologically grounded domains of QoL in older ages based on the pyramid of needs (Maslow, Reference Maslow1943) and aspires to be a scale that provides a comparable score across societal contexts (Higgs et al., Reference Higgs, Hyde, Wiggins and Blane2003; Hyde et al., Reference Hyde, Wiggins, Higgs and Blane2003). Although each of these domains stands by itself, control and autonomy together reflect the ability to intervene in the environment and be free of excessive external intervention, whilst self-realisation and pleasure indicate the presence of satisfying and meaningful activities in a person's life (Higgs et al., Reference Higgs, Hyde, Wiggins and Blane2003; Platts et al., Reference Platts, Webb, Zins, Goldberg and Netuveli2015).

Although Borrat-Besson et al. (Reference Borrat-Besson, Ryser and Gonçalves2015) raised some concerns on the comparability of CASP-12 across SHARE countries and the consistency of the autonomy domain, the scale is still the most developed indicator of QoL adjusted for the older population. Then, the CASP-12 scale was designed for the measurement of QoL in younger old age (Higgs et al., Reference Higgs, Hyde, Wiggins and Blane2003; Hyde et al., Reference Hyde, Wiggins, Higgs and Blane2003), being also applicable to very old adults (Gjonça et al., Reference Gjonça, Stafford, Zaninotto, Nazroo, Wood, Banks, Lessof, Nazroo, Rogers, Stafford and Steptoe2010; Lakomý and Petrová Kafková, Reference Lakomý and Petrová Kafková2017) due to the overlapping life priorities of these two phases (Baltes and Smith, Reference Baltes and Smith2003; Krause, Reference Krause2007). Each of the four domains is measured using three items on a four-point scale. Hence, the CASP-12 scale can take values between 12 and 48 and captures the multi-dimensional nature of the concept. Furthermore, this variable makes it possible to estimate models based on linear regression that predict the values of CASP based on explanatory and control variables using the value changes across the waves.

Main explanatory variables

The present paper examines the effect of roles prescribed by active ageing, using all important activities as explanatory variables. The employed roles belong to various sections of the SHARE dataset with their measurement taking various forms. The aims of variable transformations were (a) to produce a simple binary indicator for each activity with sufficient within-person variation, and (b) to fit the measurement of any particular activity to its conceptualisation within the active ageing approach as well as possible.

The labour force participation was enquired about by the question ‘In general, which of the following best describes your current employment situation?’, with options listed. This indicator groups respondents into categories of economically active – employed, self-employed or unemployed – and economically inactive – retired, home-makers, rentiers or permanently disabled (the latter one is the reference category). The category of unemployed is merged with working older adults, as unemployment is more similar to work than retirement in some of its outcomes (Lakomý and Kreidl, Reference Lakomý and Kreidl2015) and unemployment is also connected to active ageing, which supports prolonged labour force participation without guaranteeing jobs (Timonen, Reference Timonen2016). Despite these arguments, some older workers may get discouraged by long-term unemployment (Rife and First, Reference Rife and First1989; Maestas and Li, Reference Maestas and Li2006; Axelrad et al., Reference Axelrad, Malul and Luski2018) and experience a lower QoL. However, sensitivity analysis of REM and FEM, (a) dropping the unemployed from the models and (b) including unemployed older adults to the group of economically inactive, revealed no substantive differences in the results.

The ‘care outside household’ variable indicates care or help provided to any recipient monthly or more often, and ‘care within household’ indicates more intensive and personal care (daily is the only intensity measured by SHARE) for anybody living in the same household; not providing any care or help of monthly frequency is the reference. These two variables were constructed from a set of more-specific questions covering the type, recipient and frequency of each care-giving relationship. The care-giving outside household was asked in the form ‘In the last twelve months, have you personally given any kind of help listed on this card to a family member from outside the household, a friend or neighbour?’ and many other questions including looking after grandchild(ren). The indicator of care-giving within the household is based on the item ‘Is there someone living in this household whom you have helped regularly during the last twelve months with personal care, such as washing, getting out of bed, or dressing?’

The variables for volunteering, educational courses, sports or social club, political organisation and physical activity indicate whether the respondent engages in an activity ‘at least monthly’ (value 1) or ‘less often/not at all’ (value 0 as the reference). The exact wording was ‘How often do you engage in vigorous physical activity, such as sports, heavy housework, or a job that involves physical labour?’ for an indicator of physical activity and ‘Which of the activities listed on this card – if any – have you done in the past twelve months?’ for all other indicators. The other activities available in all three waves are ‘volunteer or charity work’, ‘educational or training course’, ‘sport, social, or other kind of club’ and ‘participation in a political or community-related organisation’. Most of the measured activities take diverse content and meaning – this cannot be reflected by the data available, but the study aims to show the prevailing effect of each type of activity rather than the consequences of specific situations.

Control variables

Gender, education, country and other time-invariant variables are not included in FEM because they are controlled automatically. Thus, the FEM presented contain four time-variant control variables. Age is accompanied by age squared to identify a potentially non-linear effect – these two variables are centred on their mean to enable the interpretation of the intercept. The subjective economic situation is measured by the question ‘Would you say that your household is able to make ends meet…’ with the following options: with great difficulty (the reference category), with some difficulty, fairly easily and easily. The REM controls all variables of FEM and additionally gender, health, education and country. Subjective health status is also measured directly using the options of poor (reference), fair, good, very good and excellent health. Gender has the categories male = 0 (reference) and female = 1, the level of education, as measured by the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) scale, divides respondents into groups with primary (ISCED 0, 1; reference), secondary (ISCED 2–4) and tertiary education (ISCED 5, 6). Finally, the country is included in the REM as a set of binary variables.

Results

Comparison of REM and FEM

Table 3 presents the REM and FEM for the whole sample. REM shows five significantly positive effects (ranging from 0.180 to 0.647) and one negative effect (−1.246) of performed roles on subjective QoL, which means that most of the examined activities increase QoL over time. Specifically, labour force participation, volunteering, physical activity, engagement in a sports club and participation in a political organisation are beneficial for QoL, which supports the assumptions of the active ageing approach. Only care-giving within the household has a negative effect; the coefficients of care provided outside the household and attendance of educational courses are not significant. Men, older adults with a higher level of education and those living with a partner have a higher QoL. Further, age has a non-linear effect, implying the increase of QoL with age followed by a reversed trend at a higher age, whilst the effects of a good financial situation and good health are presumably beneficial. However, FEM has the potential to identify spurious effects of REM connected to potential selection bias in REM.

Table 3. Random-effects and fixed-effects regression models predicting subjective quality of life

Notes: SE: standard error. Ref.: reference category. ISCED: International Standard Classification of Education.

Source: Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), Waves 4, 5 and 6, author's calculations.

Significance levels: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

The magnitude and significance of coefficients in FEM, which also indicate the impact of change over time, is much lower (Table 3). On the one hand, the positive coefficients from 0.280 to 0.347 still suggest that starting volunteering, physical activity or participation in a sports club between waves has a positive effect (and stopping them has a negative effect) on subjective QoL, whilst care-giving within the household decreases QoL. On the other hand, starting with labour force participation and organised political activity do not increase QoL in time, with even the significant coefficients for activities dropping substantially. Apart from a partner in the household, all control variables have significant fixed effects, although decreased in magnitude. The control variables could also be used in interactions with activities. For instance, the effect of activities could vary strongly by gender (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Leibbrandt and Moon2011; Rozanova et al., Reference Rozanova, Keating and Eales2012). However, the interactions are generally not significant, and the only notable difference based on gender is a slightly more positive effect of physical activities of men. Generally, the standard errors of most coefficients are 0.02–0.08 higher in FEM than in REM, which implies a lower efficiency of FEM. Moreover, the difference between the coefficients of these models signifies that a large part of the random effects can be accounted for by some time-invariant factors controlled only in FEM. The difference between models being confirmed by the Hausman test with <0.0001, FEM provides less-effective estimation, but also less-biased results.

Variation in FEM by welfare regime

Table 4 shows the results of FEM as a less-biased method for each European region separately. The results show a robust positive effect of financial situation on QoL across regions, whilst the non-linear effect of age is not significant only in Mediterranean countries. In contrast, the coefficients for activities vary much more in the European context. Changes in labour force participation affect QoL in the opposite direction in social-democratic and Mediterranean countries, although these substantive effects (−0.343 and 0.512) are not significant (p = 0.215 and p = 0.235) due to the lower effectiveness of the estimation. Care-giving within the household has a strong negative effect, −1.294 in post-communist countries, −1.272 in Mediterranean countries and −0.868 in conservative countries, but none in social-democratic countries. Starting volunteering between waves increases QoL only in social-democratic and Mediterranean countries, with both statistically and substantively significant coefficients, 0.448 and 1.008. Participation in a sports or social club has a coefficient of 1.266 with p < 0.001 in Mediterranean countries, but no effect whatsoever in the other regions. Care-giving outside the household, taking an educational course and participating in a political organisation have neither a substantially nor statistically significant effect under any welfare regime. Finally, physical activity is slightly beneficial on the border of p = 0.05 with virtually identical coefficients between 0.326 and 0.348 in all regions. Generally, the impact of roles on QoL differs across Europe, but the overall effects are rather small and almost negligible compared to the effects of age and economic conditions.

Table 4. Fixed-effects regression models predicting subjective quality of life sorted by European region

Notes: The group of social-democratic countries consists of Denmark and Sweden, conservative countries consists of Austria, Belgium, France and Germany, Mediterranean countries consists of Italy and Spain and post-communist countries consists of the Czech Republic, Estonia and Slovenia. Ref.: reference category.

Source: Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), Waves 4, 5 and 6, author's calculations.

Significance levels: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Conclusion and discussion

This paper examines the effect of roles supported by an active ageing approach on subjective QoL and the differences between these effects based on differences across European macro-regions that reflect different socio-economic, cultural and institutional contexts. This topic is crucial amidst the extensive support of the tested activities by the active ageing policies due to its proclaimed uniform contribution to the QoL of older adults (Walker, Reference Walker2009; United Nations Economic Commission for Europe and European Commission, 2015; Zaidi et al., Reference Zaidi, Gasior, Zolyomi, Schmidt, Rodrigues and Marin2017; Varlamova, Reference Varlamova2018). The effect of specific activities has been repeatedly studied, but this research extends the current understanding by employing several novelties. These are (a) all concerned activities are included in one estimation to control for each other, (b) a within-person estimator is used to evaluate changes in panel data with control for time-invariant factors, and (c) potential differences in the effect of roles across four European regions are explored. The panel analysis of the SHARE data resulted in several empirical and theoretical contributions – namely only weak or not statistically significant beneficial effects of supported activities – elaborated below.

First, the effects of activities supported by the active ageing perspective in fixed-effects regression are much weaker or even non-existent compared to beneficial effects estimated by random-effects regression. This result suggests that the effects of REM (and of many cross-sectional studies) can be explained by some unobserved variables, such as norms of in-groups, individual values, role centrality or role meaningfulness (Hornsey, Reference Hornsey2008; Adams et al., Reference Adams, Leibbrandt and Moon2011). Furthermore, the REM and findings from previous cross-sectional studies may overestimate the association between the examined social activities and QoL. Therefore, the effect of many activities in a panel perspective – care-giving outside the household and participation in the labour force, training and political organisations – is not beneficial and the effect of care-giving within the household is even strongly negative. The prevailing net effect of starting or ending activity by a specific person is generally less positive than the effect in the previous studies, which usually did not adopt the more-robust methodological approach of the present paper (Walker, Reference Walker and Walker2004; Katz, Reference Katz2009; Siegrist and Wahrendorf, Reference Siegrist and Wahrendorf2009; Adams et al., Reference Adams, Leibbrandt and Moon2011; Potočnik and Sonnentag, Reference Potočnik and Sonnentag2013). The reasons for prevailingly not significant effects of roles can be (a) the use of a less-biased statistical technique based on panel data, (b) control for important activities in later life, and (c) to some extent also the lower efficiency of estimates because of a reduced sample.

Second, participation in volunteering, sports or social club, and physical activity is beneficial in FEM for the pooled sample of European countries, but their effects are not significant in some regions. The regional differences in the effect of activities suggest their context-specific role in the lives of older adults, which is not reflected by the active ageing paradigm (Timonen, Reference Timonen2016; de São José et al., Reference De São José, Timonen, Amado and Santos2017; Marsillas et al., Reference Marsillas, De Donder, Kardol, van Regenmortel, Dury, Brosens, Smetcoren, Braña and Varela2017) and is mostly in line with the expectations based on the concept of structured ambivalence and the social identity theory. The substantially positive effect of labour force participation in less-prosperous regions compared to the negative effect in more-prosperous regions may thus be an outcome of the relative importance of paid work in various economic settings (Borges Neves et al., Reference Borges Neves, Barbosa, Matos, Rodrigues, Machado, Börsch-Supan, Brandt, Litwin and Weber2013; Hofäcker, Reference Hofäcker2015; Lakomý, Reference Lakomý2019). Whilst the higher prevalence of care-giving within the household in Mediterranean countries is related to more-frequent co-residence (Jappens and Van Bavel, Reference Jappens and Van Bavel2012; Albertini and Kohli, Reference Albertini and Kohli2013), the not statistically significant negative effect of this activity in social-democratic countries may reflect the higher availability of formal care in that context (Daatland and Lowenstein, Reference Daatland and Lowenstein2005; Fokkema et al., Reference Fokkema, ter Bekke and Dykstra2008; Brandt et al., Reference Brandt, Haberkern and Szydlik2009). The negative association of care-giving within a household with QoL in three European regions may be explained by the location of care and strength of obligations (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Bierman and Penning2020). Another explanation could be the adverse effect on QoL in measured domains of autonomy and control over life (Di Novi et al., Reference Di Novi, Jacobs and Migheli2015). In contrast to the expected role of availability of formal care, the strength of familial norms does not correlate with the outcomes of care-giving as expected by the concept of structured ambivalence (Connidis and McMullin, Reference Connidis and McMullin2002a, Reference Connidis and McMullin2002b), as the effect of care-giving outside the household is not more positive in the Mediterranean and post-communist countries. Finally, stronger civic norms could account for the positive effect of volunteering in social-democratic countries based on the higher social appreciation of these activities and lower structured ambivalence, if they are performed (Neuberger and Haberkern, Reference Neuberger and Haberkern2014).

Third, the weak and unstable outcomes of activities can be contrasted with the effect of age, economic situation, education and health on QoL, which is strong and robust. Hence, income security and availability of health care form subjective QoL in later life much more than additional roles. Although health and income may be strengthened by some types of activities (Thomas, Reference Thomas2011; Hofäcker and Naumann, Reference Hofäcker and Naumann2015), availability of resources and services seems impossible to replace in the quest for an improvement of QoL (Rozanova et al., Reference Rozanova, Keating and Eales2012; Timonen, Reference Timonen2016).

Fourth, the paper argues that the active ageing approach is based on normative and empirically dubious assumptions. The presented findings challenge those of active ageing policy, but also their theoretical underpinnings in the form of the active ageing concept and the activity theory. Especially serious consequences has the active ageing approach as an official social policy approach to the ageing of the EU, which needs to be revisited according to the findings of (not only) this study. The process of revising concerns also activity theory, which needs to accept that only meaningful and freely chosen activities are beneficial (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Leibbrandt and Moon2011; Rozanova et al., Reference Rozanova, Keating and Eales2012) and this paper illustrates that the overall effect of activities is not substantial. More valid proved to be the social identity theory, which makes it possible to explain varying outcomes of activities with different meanings – such as volunteering and participation in social clubs – by social group norms and salience. Finally, the concept of structured ambivalence (Connidis and McMullin, Reference Connidis and McMullin2002b) is beneficial for explaining the contextual variance in activity outcomes such as the positive effect of volunteering in countries with stronger civic norms. These approaches address much better both the variation of activity outcomes and a call for replacing ‘absolute notions’ of social gerontology by probabilistic theories (George, Reference George1993; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Ajrouch and Hillcoat-Nallétamby2010) and for a probabilistic rather than causal approach regarding later-life concepts, which could end the theory-poor state of this field (Moulaert et al., Reference Moulaert, Wanka and Drilling2018). In sum, this paper argues that social research and social policies should reflect the varying – and generally weak – effects of activities in later life identified in this study and consider revising its theoretical underpinnings.

Most limitations of this study stem from the nature of the data, originally not collected for the purposes of the study. First, most of the activities were measured by one closed item used as a binary variable in the analysis. As a result, the regression model distinguishes neither the frequency of the activity nor further details on its particular form. Second, a mild within-person variability of some explanatory variables may contribute to some unstable or not significant fixed effects. Third, the poor availability of panel data means that each European region is represented only by two, thre, or four countries. These countries within regions are similar in many respects but still contain hidden variation. Additionally, no country-level indicators in the data decrease the applicability of the structured ambivalence concept. Finally, fixed-effects regression performed on the panel data does not eliminate all sources of possible selection or endogeneity bias. Despite these reflected limitations, the paper presents the results that are important for research on QoL in older ages and for European social policies aiming to increase this QoL. Nevertheless, more research is needed to test and develop the findings of this study in further comparative, longitudinal and multilevel studies.

Data

This paper uses data from SHARE Waves 4, 5 and 6 (DOIs: 10.6103/SHARE.w4.600, 10.6103/SHARE.w5.600, 10.6103/SHARE.w6.600), see Börsch-Supan et al. (Reference Börsch-Supan, Brandt, Hunkler, Kneip, Korbmacher, Malter, Schaan, Stuck and Zuber2013) for methodological details. The SHARE data collection has been primarily funded by the European Commission through FP5 (QLK6-CT-2001-00360), FP6 (SHARE-I3: RII-CT-2006-062193, COMPARE: CIT5-CT-2005-028857, SHARELIFE: CIT4-CT-2006-028812) and FP7 (SHARE-PREP: No. 211909, SHARE-LEAP: No. 227822, SHARE M4: No. 261982). Additional funding from the German Ministry of Education and Research, the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science, the US National Institute on Aging (U01_AG09740-13S2, P01_AG005842, P01_AG08291, P30_AG12815, R21_AG025169, Y1-AG-4553-01, IAG_BSR06-11, OGHA_04-064, HHSN271201300071C) and from various national funding sources is gratefully acknowledged (see www.share-project.org).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge Martin Kreidl (Masaryk University) for valuable advice and vigorous commenting on this study. The author would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editor Valeria Bordone for a repeated careful consideration of this study and its significant improvement.