The results of Kenya’s 2007 general elections are contested by the political opposition. The disagreement quickly descends into mass-scale violence with ethnic overtones (which becomes the Kenya 2007-08 post-election violence, or PEV). A few months later, there has been massive displacement of people and over 1,300 deaths reported. Elite fragmentation, normalization of violence, low public trust in state institutions, and unaddressed historical injustices have conjured up a tragic crisis (Nic Cheeseman, “The Kenyan elections of 2007: An Introduction” [Journal of Eastern African Studies 2 (2): 166–84, 2008]). An elite pact puts a stop to the violence, and the country is urged—over the next five years—to accept, forget, and move on.

On June 1, 2009, during formal celebrations of Madaraka (self-rule) day, Boniface Mwangi, a former photojournalist with Kenya’s Standard newspaper, attempts to heckle and interrupt the president’s speech—demanding that he, the president, should address the plight of people who remained displaced after the 2007-08 PEV. The police beat and arrest him. Refusing to accept and move on, Mwangi becomes the face of a new kind of political activism in Kenya, one that uses art and street protest as its main medium.

Softie, a film produced by Toni Kamau—the youngest female African documentary producer to be invited to become a member of the documentary branch of the Academy for Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences—and directed by Sam Soko—the co-founder of a Kenyan production company that produced the 2018 Academy Award-nominated short fiction film, Watu Wote (All people)—follows Mwangi’s life during and after the 2007-08 PEV watershed. As a photojournalist who won the CNN Africa photojournalist of the Year Award twice, Mwangi was caught right in the middle of the cusp: “I could go and take pictures in the slums of Mathare, Kibera, then come to the newsroom in the city centre, and guys are having coffee, like everything is normal,” he says in the film. He later resigned his job with the Standard.

Perhaps those were the beginnings of a later-created, overbearing “peace narrative.” After the main contenders during the disputed elections, former President Mwai Kibaki and former Prime Minister Raila Odinga, became uneasy “comrades” in a search for “peace” against larger and more evil forces such as justice, calls for this “peace” intensified, becoming increasingly disciplinary and forbidding. As Kenyan writer and academic Keguro Macharia notes, “‘peace’ became a way of disciplining affect, refusing politics, and promoting disengagement” (Keguro Macharia, “Beyond peace” [March 9, 2013, Kenya Elections 2013 < https://kenyaelections2013.wordpress.com/2013/03/09/beyond-peace-keguro-macharia/). Mwangi, who was born in 1983—during what has been referred to as the “Dark era” of Kenyan politics—took charge of the shrinking public space and attempted to single-handedly reinvigorate Kenya’s fledgling democracy. But he didn’t do it alone, as the film reassuringly narrates.

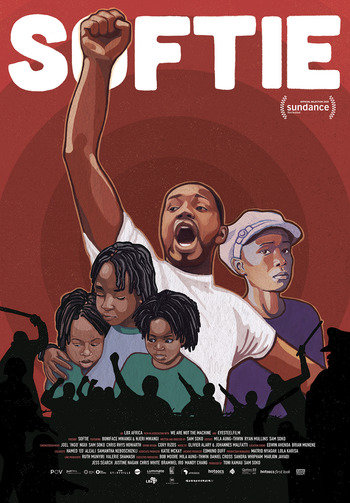

Figure 1. Image courtesy of Icarus Films.

The film begins by showing Mwangi and his associates preparing a thousand litres of cattle blood, which they would then feed and plaster onto stray pigs (inscribing onto their torsos words like M-pigs); this was part of a protest march organized by Mwangi against a move by Kenyan MPs to increase their salaries to USD10,000 a few months after they were sworn into office in 2013. Standing beside them holding a baby is Njeri Mwangi, Mwangi’s wife, whose characterization in the film moves swiftly from the role of supporting (at times worried) wife, to an unassailable factotum, the powerhouse behind Mwangi’s scatter-brained world. Viewers will learn in the film that the couple has three children, who immediately become some of the film’s most important characters, second only to their parents. In one scene, sensing that he’s about to leave the house, one of the children asks Mwangi, “Where are you going?” and Mwangi responds, “I am going to topple the government.”

The film is a veritable tapestry of Mwangi’s private and public life, the boundary of which becomes increasingly hazy as the film proceeds, climaxing with a death threat against Mwangi that forces Njeri and the children to seek asylum in Jersey City in the United States. Mwangi’s story is told through the backdrop of Kenya’s recent political history, showcasing familiar tropes of the typical post-colonial African country: corruption, inequality, injustice, and unemployment.

In another scene, Mwangi relays his decision to run for office to his wife Njeri while being interviewed. Njeri’s surprise is promptly caught on camera. His campaign experience (Mwangi vied to become the Mp for Starehe constituency in Nairobi County, losing to Charles Njangua, a musician turned politician popularly known as “Jaguar”) provides a useful smokescreen for the multiple pitfalls involved while running for office in Kenya without a hefty budget. In a place where there are deep inequalities and low public trust of public officers and politicians, voters often seek out bribes and other small favors before the election and sometimes on polling day, as a tax on a politician whom they may never see again.

Shot over the course of seven years, Softie is a landmark. It takes full advantage of the value of longitudinal growth, as the viewer literally watches as Mwangi’s children grow up. There is also a useful half-way point where the focus shifts to Njeri, who agonizes over death threats against Mwangi and Mwangi’s shadowing. “I am his wife, people don’t see me for me,” she proclaims. Njeri issues another powerful statement in the film: “We were fighting for the country, but now I feel we are just fighting for us,” she proclaims, decrying the selfishness, apathy, withdrawal, and amnesia on the part of a majority of the Kenyan public. Despite a few inconsistencies, one where a photo shot in 2007 is shown to depict events in 2017, Softie is a must-see for anyone interested in contemporary African politics, human rights studies, political science, film studies, law, and democracy.