Introduction: pop goes Nigerian Pentecostalism

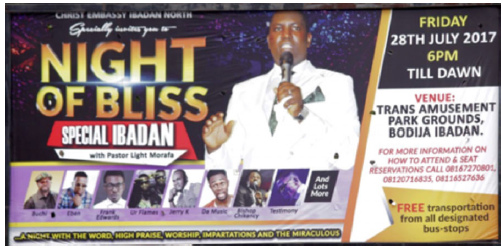

I was pulling into the parking lot of a local diner in Ibadan, the sprawling capital of Oyo State, when the huge billboard poster caught my attention (Figure 1). Posters like the one that had just quite literally arrested me are a ubiquitous fixture of the visual economy of Nigerian Pentecostalism (Ukah Reference Ukah2008); in fact, I had zipped past several that day as I conducted my business around the metropolis. But something about this particular billboard was atypical, hence my being momentarily transfixed by it. It was an invitation by Christ Embassy, Ibadan North, for a ‘Special Ibadan Night of Bliss’, and, as far as religious billboards on Nigerian highways and in the urban landscape go, it was actually run of the mill. There was, for example, the usual promise of ‘FREE transportation from all designated bus-stops’ (the ‘FREE’ was in bold red so that you couldn’t miss it) and the obligatory assurance of ‘a night with the word, high praise, worship, impartations [sic] and the miraculous’.

Figure 1. ‘Special Ibadan Night of Bliss’.

But what really piqued my curiosity was the row of thumbnail images of various individuals carefully arranged under the imposing picture of the pastor of the church, Light Morafa. As I read the names – Buchi, Eben, Frank Edwards, Ur Flames, Jerry K, Dr Music, Bishop Chikancy, Testimony – it quickly dawned on me that what I was looking at was not just another religious billboard, but a visual representation of the concurrence of Nigerian Pentecostalism and Nigerian popular culture. For, not only are Buchi and the other ‘special guests’ on the poster not your ordinary men of the cloth, they are in fact well-known figures in Nigeria’s ever expanding stand-up comedy industry.Footnote 1 What, I wondered, were comedians doing on the billboard for a religious event? And what is their role in a Pentecostal church service? Why, in any event, would a church need the ballast of the presence of several entertainment personalities? What does the need for such celebrity augmentation tell us about transformations within Nigerian Pentecostalism, and in its intriguing relationship with popular culture? What questions about the idea of space are evoked by the presence of entertainers within the church, especially in relation to tensions over sacredness and profanity and their mutual reinforcement within the Nigerian public sphere?

A section of the sociological literature on popular culture favours the idea of popular culture itself as a religion. For instance – admittedly within a specifically American context – Barry Taylor champions the possible utility of popular culture as ‘a prime resource for thinking about issues of faith and belief’, arguing that ‘[p]eople not only “find God” in the movies, they also find new ways of believing and expressing themselves spiritually’ (Reference Taylor2008: 16). Other studies have analysed the ways in which aspects of popular culture, because they exhibit or possess ‘all the trappings of a religious festival’ (Forbes Reference Forbes, Forbes and Mahan2017: 2), might qualify to be described as a religion (see, for example, Myers Reference Myers2012; Schultze Reference Schultze1986). While this literature is potent – not only in calling our attention to the complex ways in which popular culture and religion have become increasingly conjoined, but also in highlighting the role of the mass media in facilitating the coincidence of religion and popular culture – that is not my focus here. In the first place, treating popular culture as religion will inevitably draw me into the quicksand of argumentation about the proper definition of religion, a venture from which, at least within the scope of this article, the returns are certain to be meagre. Second, and given the thrust of my analysis, the idea of popular culture as religion seems less attractive, and certainly less rewarding, than an exploration of how religion and popular culture intermesh, coincide and depart, all in a social dynamic that continually throws up critical trespasses, transgressions and unforeseen coalitions.

Nigerian Pentecostalism, with its appetite for spectacle (Obadare Reference Obadare2020), its penchant for theatre and its infinitely pragmatic theology (Burgess Reference Burgess2008; Wariboko Reference Wariboko2019), furnishes an interesting milieu for such an exploration. For one thing, its embrace – control, some would say – of the media and the creative mobilization of its affordances and platforms – in music, cinema, entertainment and social media (Hackett and Soares Reference Hackett and Soares2015; Hackett Reference Hackett1998; Kalu Reference Kalu2007; Larkin Reference Larkin, Hackett and Soares2015; Meyer and Moors Reference Meyer and Moors2001; see also Hoover and Clark Reference Hoover and Clark2002) – places Pentecostalism firmly within the vortex of Nigerian popular culture. For another, and as Abimbola Adelakun has noted, the way in which Nigerian Pentecostals perform their faith is fused with the way they ‘make Pentecostalism a cultural performance’ (Reference Adelakun2017: viii), while Pentecostal performances are integral to ‘the ways the Pentecostal culture expands its territory in Nigeria’. Therefore, ‘[b]y absorbing materials from “the world” that resonates [sic] with its religious values and dispensing them back into the public realm, the society gradually becomes “pentecostalized” thus blurring the lines between what is considered sacred or secular’ (ibid.: 62). Nigerian Pentecostalism and popular culture are joined at the hip in other instructive ways. With respect to Nollywood, the Nigerian cinema industry, for instance, Akin Adesokan (Reference Adesokan and Olaniyan2017: 191) has suggested that, ‘[s]ociologically, the explosion of Nollywood films is very much linked to the logic of informalization at work in the growth’ of Pentecostal churches. I would add that both are offspring of the 1980s era of structural adjustment and they continue to be propelled, in not so different ways, by an economic imperative.

In any event, whereas Nollywood can be trusted to archive the foibles and contradictions of the Pentecostal movement, with a genre of films devoted to what Adesokan calls ‘the chiliastic worldviews of Pentecostalism’ (Reference Adesokan and Olaniyan2017: 192), stand-up comedians, when they are not playing pretend pastors (see, for instance, Woli Arole and Woli Agba), set up Pentecostal pastors as targets of savage mockery (Adejunmobi Reference Adejunmobi, Newell and Okome2014).Footnote 2 In so doing, paradoxically, they provide a vehicle through which Pentecostalism spreads into and permeates popular culture. Finally, in the emergence of pastoring as a career for an increasing number of Nollywood stars and celebrities, we see an extension and further consolidation of the mutual entanglement of Nigerian Pentecostalism and popular culture (Figure 2).Footnote 3

Figure 2. The poster for a show, ‘Comedy Goes 2 Church’, by popular stand-up comedian Acapella at Victory Dome David’s Christian Centre, Lagos.

Consequently, I bring to this analysis two complementary research and intellectual interests. First, within the ambit of popular culture in general, I am interested in comedy as a coping mechanism and vehicle of everyday resistance for a civil society desperate to avoid state censure (Obadare Reference Obadare2010; Filani Reference Filani2015; Yékú Reference Yékú2016). Second, positing Pentecostalism as the lodestar of the Nigerian Fourth Republic (1999–), I evaluate it as a cultural force that impresses on everyday life even as it is striated with the markings and peculiarities of the Nigerian condition (Obadare Reference Obadare2018). Against this backdrop, my overriding desire is to illuminate Pentecostalism and the sociological matrix within which it has enjoyed quite astonishing growth. With insights, claims and perspectives from the economics of religion, I apprehend emergent patterns in Nigerian Pentecostalism, primarily the postulated enfolding of Pentecostalism and popular culture.

In my approach to the marriage of Pentecostalism and popular culture, I draw inspiration from Achille Mbembe’s idea of ‘the postcolonial dramaturgy’. In his On the Postcolony, Mbembe enumerates the ensemble of characters involved in the reproduction of what he calls ‘an economy of pleasure’, and courtesy of whom ‘the postcolony has become a world of narcissistic self-gratification’ (Reference Mbembe2001: 123). Who is included in this pantheon interests me less than the sociological need for spectacles that, while doing the work of pleasure: (1) help distract from the pain and disappointments of everyday life in the postcolony; and (2) further the state’s project of soft domination through demobilization. Within this framework, we are forced to conclude that the comedian and the pastor are engaged in the same business of enchantment. While involved in the staging of spectacles (of amusement and of piety respectively), their coming together within the theoretically sacred space of the church reinforces the idea of the church as a space of pure theatre, while making the distinction between the profane and the sacred itself almost redundant. I return to this theme in the conclusion. The strong public presence of Pentecostals and Pentecostalism is, needless to say, less central in On the Postcolony, but that omission is overridden by the intellectual licence the work grants us to take the apparently unserious seriously; to see in otherwise discounted gestures and performances pointers to the rude toponymies and the political and cultural vitality of African civil society. As I have argued elsewhere (Obadare Reference Obadare2016a), humour is the enduring currency of this underrated and often misunderstood world, the barb directed at the state’s jugular and the balm that helps soothe the asperities of a harsh existence. If the following passage from Donna Goldstein’s work on everyday life in Brazil’s shantytowns resonates, it is precisely because it could very well have been written about (the mood) anywhere in peri-urban Nigeria:

Despite the fact that I was caught up in a community where life was all too clearly hard, everywhere I turned I seemed to hear laughter. I gradually came to realize, first in my gut, later in my head, that there was much more behind the humor than I first realized. This humor was a kind of running commentary about the political and economic structures that made up the context within which the people of Rio’s shantytowns made their lives – an indirect dialogue, sometimes critical, often ambivalent, always (at least partially) hidden, about the contradictions of poverty in the midst of late capitalism. (Goldstein Reference Goldstein2003: 2)

This article advances two arguments. First, I argue that the main explanation for the convergence of Nigerian Pentecostalism and popular culture, as symbolized by the trend of inviting comedians and entertainers into church services and other religious events (more on which presently), is the imperative for product differentiation in a saturated and ultra-competitive religious marketplace. By saturation, I allude to the reality that ‘the depth of the involvement of Pentecostal Christianity in everyday life in Nigeria is so total’ (Adesokan Reference Adesokan and Olaniyan2017: 203) that no aspect of life – politics, economics, education, the media, sport, entertainment – is either unmarked by or imaginable without it. From this perspective, inviting entertainers into churches in order to stimulate the congregation is an attempt either to hold onto that congregation (the market share, if you will) or to expand it by poaching ‘customers’ from the competition. Either way, crucially, a commercial logic predominates.

Second, I argue that this commercial logic is itself underwritten by a cultural paradigm whose guiding ethos is anti-essentialist, a fact that may or may not always be obvious even to individual church leaders. I am claiming that, at least in the western part of Nigeria, Nigerian Pentecostalism operates under the star of a Yorùbá liberalism whose theological flexibility: (1) valorizes identity or membership of the Yorùbá community at the expense of claims of denominational affiliation (Peel Reference Peel2016; Adebanwi Reference Adebanwi2014; Obadare Reference Obadare2017b); and (2) licenses, or at least does not explicitly frown upon, mobility within or even across faiths as part of a legitimate human quest for ‘power’. Therefore, while, as the first argument insists, the decision by several church leaders to bring popular entertainers into their churches most probably is due to a commercial impulse, the foundational pragmatism of the Yorùbá worldview explains why many of them (church leaders) did not find the strategy problematic in the first instance. To be sure, and as I show presently through the ensuing controversy, this pragmatism – or ‘Yorùbá conditions’, as Peel (Reference Peel2016) describes it – is not uncontroversial. In fact, the passion with which arguments are often traded is a reminder of tensions perennially at work under the façade of perfect amity – even more so when those literally joined in battle are otherwise politically competitive Christian and Muslim combatants. Nevertheless, what matters is that those ‘conditions’ hold, and that their resilience, especially in the context of competition among Pentecostal churches, may be reinforced by purely economic calculations.

In the next section, through a series of vignettes, I provide further illustration of the imbrication of Nigerian Pentecostalism with popular culture. Then, I examine the literature on the economics of religion with the aim of exploring the extent to which its principles and insights are applicable not just to Nigerian Pentecostalism broadly but specifically in relation to the need for both distinction and survival in a competitive religious economy. In the concluding section, I raise ancillary issues at the intersection of Pentecostalism and space – sacred and profane – in contemporary Nigeria, showing how they might be mobilized to deepen our understanding of the religious economy.

Pasuma goes to church

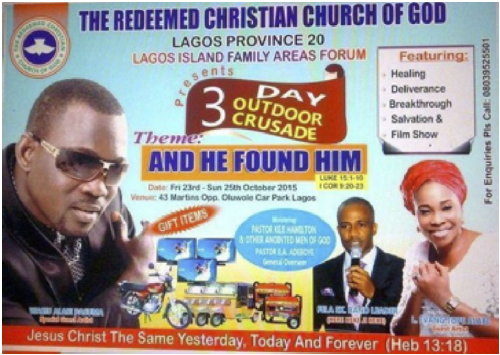

In October 2015, the Redeemed Christian Church of God (RCCG), Lagos Province 20, was in the middle of preparations for a three-day outdoor crusade, and Pastor Toyin Ogundipe, who is also Professor of Botany at the University of Lagos, needed a personality who could be relied on to galvanize the audience. After weighing his options, Pastor Ogundipe decided that popular Fuji musician Alhaji Wasiu Alabi, better known as Pasuma (or Paso for short), was the ideal candidate for the job, and he rang him up. Although a born-again Christian, Pastor Ogundipe, a self-confessed lover of Fuji music, apparently saw nothing wrong in inviting Pasuma, a practising Muslim and one of the most famous faces in the Nigerian entertainment industry, to come and fire up a Christian audience. Pasuma would later confirm as much in an interview,Footnote 4 pointing out that, during the telephone conversation with Pastor Ogundipe, the latter had brushed aside his initial rejection of the invitation by reassuring him that all he needed from him, Pasuma, was to ‘come there … so we can get one or two or three people to change their lives. We want to use you to change some people’s hearts.’Footnote 5

Although Pasuma and Pastor Ogundipe shook hands on a deal, the crusade would not go ahead as planned, for hardly had the poster (Figure 3) of the event featuring, among other things, a large picture of Pasuma sporting his trademark dark glasses gone into circulation than it ran into a storm of criticism, mostly centring on the propriety of inviting into the ‘sacred space’ of a church ‘crusade’ a ‘Special Guest Artist’ who happened to be a practising Muslim and whose music is notorious for its profanity and ribaldry. As criticism mounted, the RCCG hierarchy intervened quickly by cancelling the planned crusade and suspending the errant pastor.

Figure 3. Popular Fuji musician Pasuma (left) on the crusade poster.

As it happens, Pastor Ogundipe was not the first pastor of a major Pentecostal church to invite a popular entertainer to, as it were, light up his congregation. In April of the same year, Senior Pastor Bolaji Idowu of Harvesters International Christian Centre, Lekki, Lagos, had drawn flak for inviting singer-songwriter Korede Bello to perform his hit song ‘God win’ to the congregation in celebration of Easter Sunday. Of the many condemnations of Pastor Idowu, the pained statement (Abraham Reference Abraham2015) by US-based Pastor Olusola Fabunmi of the RCCG, City of Faith, Maryland, went furthest in summarizing the concerns of those worried by what they saw as the latest instance of the church’s seemingly inexorable surrender to ‘the world’:

But it’s written here, that when we chose the way of the world, we have clearly chosen our paths; becoming an enemy of God. Please, there must be a clearly defined boundary of who sings, and/or ministers in churches. Some of the questions that come to mind are: is he born again? Sanctified with the spirit of God and baptized in the Holy Spirit? Also, let’s ask ourselves, what’s even the purpose of people singing in churches and Christian concerts? … So I believe very strongly that one major purpose of choristers or Psalmists singing is to prepare the minds and hearts of the people for the word of God.

Pastor Fabunmi’s anxiety about the church ‘surrendering to the world’ appears to have been ignored. In the past couple of years, several entertainers and Nollywood stars, including King Wasiu Ayinde Marshal (KWAM 1),Footnote 6 Patience Ozokwor, Osita Iheme (Pawpaw, of the Aki and Pawpaw duo), comedian Akpororo (Jephthah Bowoto) musician Iyanya (Iyanya Onoyom Mbuk), actors Ini Edo and Desmond Elliot, and actor-comedian Funke Akindele (aka Jenifa) have honoured invitations by various churches to ‘boost attendance’ at church services and sundry religious events. Such, indeed, has been the regularity of these invitations that Musa Atake, general secretary of the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN), echoing Pastor Fabunmi’s demurral, was forced to issue a statement condemning them:

If the church has gotten to a place where it is making adverts (inviting celebrities) like the world, then we are in trouble. The church is a serious place where we go to worship, not where we go for entertainment. In my personal opinion, I don’t support it, because this will only divert attention of people from Christ to human beings which is not supposed to be so.

He continued:

If, for example, I am a fan of one of these celebrities and they are invited, I’ll stop thinking about my salvation, about Christ and my walk with the Lord, I’ll rather be focusing on that person. Once the church gets to that level, we are trying to side-track ourselves from the gospel message to a worldly kind of entertainment, which is not supposed to be so. (Iroanusi Reference Iroanusi2017)

The strongest condemnation perhaps is the statement by Pastor Mike Bamiloye, who, in an address to ‘Christians – ALL denominations’ posted on his Facebook page, expressed his disgust at the new trend. I reproduce the address in full because it speaks to some of the issues, particularly concerns about desecration, that this article addresses:

For a long while I have questioned the inclusion of COMEDY in Church events. What do I question? The fact that the comedians brought in are allowed to make jokes of scriptures, the Blood of Jesus, speaking in tongues, the throne of grace etc. AND WE SIT THERE LAUGHING!

What are we laughing at? What is funny? Mocking God and Christ and the Holy Spirit and the Word is funny????

We hear of other religionsFootnote 7 where they are obsessed with protecting the image of their Leader and we gleefully allow people to MOCK our Leader JESUS CHRIST and the Holy Spirit and thereby indirectly MOCKING GOD!!! They look at us with disdain because we are BAD AMBASSADORS of our faith!

I was thinking of all this since Friday when a comedian was allowed on the stage at the EXPERIENCE to use a scripture in the Old Testament as foundation for his jokes! I LAUGHED also but later felt badly convicted and I said I will speak out …

So there it is: what is the stance you will take??? Join the revelers or stand against MOCKERY in the name of COMEDY in Church activities and events??? I have said my own! (Chioma Reference Chioma2016; see also Augoye Reference Augoye2017)

Denunciations by Pastors Fabunmi and Bamiloye and the CAN general secretary are a reminder that approval of this practice is not unconditional, either within Pentecostal churches or in Nigerian Christianity more broadly. That remains true even when some pastors defend such invitations on the grounds that the celebrities in question are Christians, conveniently ignoring the fact that some are in fact self-confessed Muslims. At any rate, the objections signal fundamental tensions and disagreements among Nigerian Pentecostals on how to relate to the world in general and the world of popular culture more specifically. From the standpoint of the community, it makes a difference whether they, i.e. Pentecostals, seek to leave their imprint on a popular culture ‘out there’ – in which case accommodations may be more easily forged – or whether agents ‘from the world’ are invited into the hallowed ground of the church or even the service. These negotiations notwithstanding, the more important issue, as indicated earlier, is that the practice in question is just one aspect of the alliance between Pentecostalism and popular culture. We should also note, parenthetically, the irony of Pastor Bamiloye in decrying the invitation of comedians and entertainers into the church, given that, as dramatist, actor, producer and owner of a television station (Mount Zion Television) – in short, a perfect symbol of the fusion of religion, popular culture and entrepreneurship – Bamiloye, recognized as a pioneer in the Nigerian Christian film industry, played a leading role in introducing Nigerian Pentecostalism to popular culture via audiovisual media.

One other important expression of the coincidence of Nigerian Pentecostalism and popular culture is the figure of what I call the gospel comedian, who, as mentioned earlier, is neither entirely a comedian nor entirely a pastor, but one whose performances speak to an agent immersed in both worlds.Footnote 8 I have already mentioned Woli Arole (real name Bayegun Oluwatoyin) and Woli Agba (Ayo Ajewole) as two of the leading names in this emerging comic form. Others, in no particular order, are Akpororo (Jephthah Bowoto), Mazi Prosper, Bishop Chikancy, Buchi (Onyebuchi Ojieh), M. C. Crucsio, DA 13th Disciple (Adefuwa Oluwagbemiga), Gee Jokes (Adejobi Omogbolahan) and Aboki 4 Christ (Olufemi Michael).

If, on the one hand, gospel comedians crystallize the convergence of Pentecostalism and popular culture as hybridized agents, on the other, by extending the list of what is safe for ridicule, thus widening the frontiers of the genre, they add another hue to the palette of Yorùbá eclecticism. For instance, because some of them are self-confessed Christians, and hence speak from within the fold, gospel comedians, unlike ‘regular’ comedians, appear to enjoy greater artistic licence regarding otherwise theologically sensitive material. In fact, such is the desire of some to emphasize (the primacy of) their identities as born-again Christians that a few (Woli Arole, for instance) would typically preface their commencements with the caveat that they are not comedians. They may not be pastors either, but one thing they undoubtedly are is entrepreneurs with an eye for a quick profit. Leveraging the affordances of social media, particularly on YouTube, Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp, they have become multipurpose cultural intermediaries, as ready to celebrate the birthday of a leading socialiteFootnote 9 as they are to front various products for sponsors across the whole spectrum of corporate Nigeria.Footnote 10 In the figure of the gospel comedian, Pentecostalism, popular culture and the commercial ethic are synthesized (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Billboard for a performance by gospel musician Big Bolaji, with stand-up comedians such as Woli Arole and Woli Agba, and ‘special presence’ of Pastor Austin Ologbese of the Breakforth Church, Ibadan.

Pentecostal economics: following the money

In its African churches, most of them (literally) storefronts, prayer meetings respond to frankly mercenary desires, offering everything from cures for depression through financial advice to remedies for unemployment; casual passersby, clients really, select the services they require. Bold color advertisements for BMWs and lottery winnings adorn altars; tabloids pasted to walls and windows carry testimonials by followers whose membership was rewarded by a rush of wealth and/or an astonishing recovery of health. The ability to deliver in the here and now, itself a potent form of space–time compression, is offered as the measure of a genuinely global God, just as it is taken to explain the power of Satanism; both have the instant efficacy of the magical and the millennial. (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2000: 314–15)

Starting from Max Weber’s landmark work (Reference Weber1905) on the linkage between Protestantism and capitalism, through R. H. Tawney (Reference Tawney1926), Peter Berger (Reference Berger1963) and, more recently, studies by Iannaccone (Reference Iannaccone1991; Reference Iannaccone1992; Reference Iannaccone1995a; Reference Iannaccone1995b), Emerson and Smith (Reference Emerson and Smith2000), Finke and Stark (Reference Finke and Stark1988), Ekelund etal. (Reference Ekelund, Herbert and Tollison2006), McCleary and Barro (Reference McCleary and Barro2019) and Vatter (Reference Vatter2011), the economic dimensions and implications of religiosity have drawn copious scholarly attention.Footnote 11 Relying extensively on North American/Western religious experience, this literature attempts to explain religious behaviour through a rational choice perspective, showing that the logic of demand and supply is as useful in analysing the actions of human beings as consumers as it is in understanding their spiritual choices. For Ekelund etal., the distinguishing feature of the economics of religion ‘is the belief that religion and religious behavior are rational constructs. In religious activity, as in commercial activity, people respond to costs and benefits in a predictable way, and therefore their actions are amenable to economic analysis (as well as sociological, historical, psychological, and anthropological analysis)’ (Reference Ekelund, Herbert and Tollison2006: 3).

The economic approach to religion, while undeniably useful, is not without its critics, many of whom are dubious about the application of the tools, analogies and vocabulary of economic analysis to something as non-rational as religion and religious behaviour (McKinnon Reference McKinnon2011; Sharot Reference Sharot2002; Bruce Reference Bruce1993). Bruce, for instance, insists that ‘rational choices cannot be made in religion because the various religious options cannot be weighed vis-à-vis the transcendental goals of religion, and that, generally speaking, most social environments mitigate against the notion that religious affiliations are the result of personal preferences’ (quoted in Yong Reference Yong2009: 120). Similarly, McCloskey argues that meaning seems to matter in religion ‘in a way that it does not in the consumption of ice cream’, although she is careful to ‘except certain quasi-religious experiences of ice-cream eating, such as a double scoop of amaretto at Sweet’s on Nassau Street in Princeton’ (Reference McCloskey2005: 21).Footnote 12 Alluding to more or less the same problem, Ekelund etal. contend that ‘existing economic studies of religion share a common weakness: They do not accurately define the subject being studied. As a consequence, religion may, and often does, take on different meanings, some of which are amenable to empirical (or anecdotal) study, and some that are not’ (Reference Ekelund, Herbert and Tollison2006: 7).

These legitimate reservations notwithstanding, an economic understanding of religion or the economics of religion – irreducible, in my view, to rational choice theory – affords critical leverage to understand religious phenomena, not least because of the light it throws on the economic milieu in which certain forms of spirituality emerge, and how that milieu invariably conditions and shapes the agency of adherents. Jean and John Comaroff’s parallels between the murals (and morals) of global capitalism and those of African Charismatic Christianity should be viewed in this context.

Accordingly, an economic approach to Nigerian Pentecostalism generates insights: first, its antecedents. It goes without saying that what Marshall (Reference Marshall2009; cf. Ojo Reference Ojo2006) calls the ‘Pentecostal revolution’ was part and parcel of the broader cultural reaction to the economic dislocation of the 1980s. While, on the one hand, Pentecostal spirituality provided much-needed refuge for those whose lives had been so drastically ‘adjusted’, on the other, it opened up new horizons of economic opportunity to entrepreneurs who had been locked out of a contracted formal labour sector. It is primarily for this reason, I argue, that the history of Nigerian Pentecostalism is ultimately inseparable from a kind of ‘Prosperity Gospel’, Pentecostalism’s emergence being coeval with an economic crisis that put matters of poverty and prosperity front and centre in ordinary people’s lives (Obadare Reference Obadare2017a; cf. Kalu Reference Kalu2000; Haynes Reference Haynes2012; Ukah Reference Ukah2007).

Nigerian Pentecostalism is possessed by the economic spirit in other illuminating ways. Ukah has analysed the array of means whereby ‘[t]he church has managed to accommodate dominant consumer culture and capitalist market practices while not losing its other-worldly foci’ (Reference Ukah and Falola2005: 270). For instance, there is a ‘strong and open rivalry among Pentecostal churches for members and to attract corporate patronage and sponsorship’, to the extent that ‘the churches have become the locus of an aggressive rivalry among global and local business organizations competing for a share of the Pentecostal market for their services and products’ (ibid.). At the same time, many of the churches are run more or less as ‘business empires with the leader-founder acting as the executive director, and his wife (who usually is the second-in-command) acting as treasurer/financial secretary’ (ibid.: 272). The overarching logic, Ukah persuasively argues, is transactional, a ‘reasonable exchange relationship with God’ (ibid.: 263) in which church members ‘reap’ what they have ‘sown’ – a process that is not necessarily understood in metaphoric terms. For example, in 2012, as part of his solicitation for donor ‘Covenant Partners’,Footnote 13 Pastor Enoch Adeboye of the RCCG, warming to his métier as pastor-salesman, could not have been clearer that contributions – preferably ‘in Dollars or Pounds’ – were a form of ‘investment’. Such ‘investment’ is recoverable in ‘miracles’, but, more concretely, constitutes a semi-life warranty according to which those ‘in covenant’ for, say, ten years, were assured of being ‘kept alive for ten years’ (Obadare Reference Obadare2012). In a nutshell: you contribute to the church in direct exchange for a guaranteed life term – no more, no less.

The transactional logic apart, neither innovation (see Nyamnjoh and Carpenter Reference Nyamnjoh and Carpenter2018, for example) nor the growth process within Nigerian Pentecostalism is explicable outside the economic impulse. Regarding growth, not only does Ukah link the demographic expansion of Pentecostal Christianity with its increasing economic power, but, more provocatively, he suggests that schism within church congregations is mostly driven by an economic impulse, ‘caused by the desire to control the economic resources of the congregation’ (Reference Ukah2016: 530). Ultimately, for him, it is:

In the economic realm that the Pentecostals have made their presence felt, through ownership of property and companies and the establishment of large residential estates. As religious leaders openly embrace a neoliberal market and entrepreneurial logic, they unabashedly incorporate urban commercial practices, such as the spirit of investment and profit seeking, into an emergent Pentecostal culture driven by a theology of material success and the flaunting of economic power as a sign of grace and salvation. (Ukah Reference Ukah2016: 530–1)

It is this entrepreneurial logic, unfolding within a context of product saturation, that, I suggest, explains the embrace of popular entertainers by an increasing number of Pentecostal pastors. Product saturation speaks to the pentecostalization of everyday life in Nigeria, which is the reality of: (1) Pentecostal denominational supremacy; and (2) life in every respect bending to the ‘Pentecostal principle’ (Wariboko Reference Wariboko2011). At the same time, the Pentecostal embrace of popular entertainers, while theologically contentious, is consistent with a reconciliation with popular culture that has seen Pentecostal leaders effectively use mass media ‘in the propagation of their ideas’ (Adesokan Reference Adesokan and Olaniyan2017: 194). For such Pentecostal leaders, recruiting popular entertainers, though controversial, becomes understandable when viewed as the logical outcome of the work of salesmanship necessitated by the rigours of keeping and maintaining a congregation – not to mention keeping it entertained. As such, when Pentecostal leaders go out of their way to invite popular entertainers as a way of ‘energizing’ their congregations and augmenting church experience, they are merely extending and deepening a relationship with popular media and popular culture that seems to have been there right from the inception of Pentecostalism as a cultural force in the 1980s. The key idea, therefore, is not to portray popular culture as an invading force within the space of the church, something clearly assumed by the religious leaders who strongly objected to the invitation to popular entertainers, but rather to ponder the various ways in which Pentecostalism and popular culture are mutually entangled, illustrating their mutual transgression.

Conclusion: money, culture, space

Pentecostalism is, quintessentially, the Christianity of this consumerist paradise on earth. Its gospel of wealth and prosperity and its message of optimism both feed on and extensively use the tools and products of the information and communications processes of advanced postmodern, millennial capitalism to offer hope and grace to hundreds of millions without work now and without realistic prospects for the future. (Jeyifo Reference Jeyifo2016: 306, emphasis in the original)

I have argued that, legitimate criticisms of its assumptions, techniques and emphases notwithstanding, an economic approach to religious affairs is often fruitful and illuminating and can provide a penetrating framework for understanding the emergence, growth, innovation and other aspects of specific religious denominations. Within this framework, I have suggested that some emergent trends within Nigerian Pentecostalism, particularly the controversial phenomenon of Pentecostal leaders inviting popular entertainers to perform at church services and other religious events, are dictated by an economic logic, central to which is the need by churches to adapt to the changing conditions of an intensely competitive religious marketplace. One effect of the success of Pentecostalism as the dominant form of Christianity in Nigeria and other African countries is its numerical explosion. As Pentecostalism has exploded, so too has its appetite for space, as shown by Pentecostal appropriation of public spaces such as nightclubs, hotels and cinema halls in Nigeria (Adeboye Reference Adeboye2012).

That success, one might argue, has led to a glut in the supply of ‘religious goods’; Pentecostal churches’ cultivation of popular culture, as illustrated by the overture to popular entertainment figures, is thus in part explained by the logic of competition in a saturated religious marketplace. Logically, because the supply of what Ekelund etal. describe as ‘assurances of salvation’ now arguably exceeds demand in the Nigerian religious market, Pentecostal churches are forced to come up with all manner of ‘product differentiation’ innovations in order to either hold onto loyal patrons (existing members of the congregation) or attract new customers. That is why, for instance, the billboard advertisement of the RCCG Lagos Province 20 mentioned earlier not only features an image of Pasuma but also tantalizes prospective attendees with ‘gift items’ including flat-screen televisions, motorcycles, mass transportation tricycles popularly known as ‘Keke Marwa’ or ‘Keke NAPEP’, and electric power generators. Since ‘assurances of salvation’ are no longer enough to draw people in, churches are forced to go out of their way to offer other products (entertainment, commodities, etc.) in addition to their core product.

As mentioned earlier, this coincidence of the notionally sacred and the profane puts us in touch with one of the critical issues with which Mbembe engages, first in ‘Provisional notes on the postcolony’ (Reference Mbembe1992) and later in On the Postcolony (Reference Mbembe2001). Specifically, the apparent erasure of the border delineating the pietistic from the farcical (the theologico-theatrical, as I advance) is important for understanding the transformation of both the official and non-official cultures tackled by Mbembe, invoking Mikhail Bakhtin. Further, while Mbembe theorizes the postcolony as ‘characterized by a distinctive style of political improvisation, by a tendency to excess and a lack of proportion’ (Reference Mbembe1992: 3), the performative bricolage that is the essence of the theologico-theatrical proves that the ethic of improvisation is not contained within the political field. On the contrary – and bowing, as I have claimed, to pressure in a competitive religious marketplace – religious leaders enact devotional strategies (improvisations) that open up the church to the world of ‘obscenity’. Sacred space, we are thus reminded, ‘is not placid; it often exists at the heart of tumultuous controversies’ (Kilde Reference Kilde2008: 9). Second, ‘social power – evident in hierarchies and in relations among different groups – informs religious spaces’ (ibid.).

Nonetheless, while, as I have pursued, an economic explanation for this trend sounds plausible, it is by no means exhaustive, gaining further validation when placed within the matrix of Yorùbá metaphysical permissiveness, believed by scholars (Peel Reference Peel2016) to have originated in the dynamic copresence of three religious traditions (Islam, Christianity and indigenous Orisa) in the Yorùbá space and imagination. The point is that, given the power and widespread acceptance of this metaphysics, the invitation of popular entertainers into churches is not the problem of visceral contamination it would most certainly be in a different cultural context. But what about the fact, also noted earlier, that some of the entertainers in question are not even (nominal) Christians? Elsewhere (Obadare Reference Obadare2016b), inspired by the scholarly tradition discussed above, I have argued that a culturally mandated amity among otherwise competitive religious traditions explains Muslim adoption of Pentecostal devotional and evangelistic repertoires in western Nigeria. Therefore, the presence within the church of an entertainer who also happens to be a Muslim may not be the singular act of transgression it would appear to be at first glance, but something perhaps to be expected from a cultural economy in which accommodation (both within and between faiths) is the first and last rule. Nor, to revisit that example, is there necessarily a contradiction in a ‘born-again’ Christian such as Pastor Ogundipe being partial to Fuji music, as many Yorùbás, Muslim and Christian, in fact are. Indeed, not only has the Fuji scene always been the best place to judge the vitality or otherwise of popular culture as conducted in Yorùbá, the music itself has played an outsize role in the liberalization of the Yorùbá public sphere.

We might then conclude that, in extending an invitation to Pasuma, the Fuji exponent, Pastor Ogundipe was unwittingly validating two facts, one cultural, the other sociological. The cultural fact is that, although both the pastor and the entertainer profess allegiance to two different faiths, they remain, culturally speaking, sons of the same mother. In sociological terms, Pastor Ogundipe was underlining Fuji’s undoubted eminence as the most innovative form of popular music in contemporary western Nigeria. While a full development of this observation falls outside the remit of this article, I note in parenthesis that, over time, and in part through a process of steady appropriation that is classic Yorùbá, Fuji music has transcended its religious origins in urban working-class Muslim Ramadan ritual to become a transnational, class-neutral, crossover secular genre. And as a crossover genre, not only has it internalized the Yorùbá idea of Jesus as a cultural figure for multipurpose social invocation, which means that Christian songs of appeasement for heavenly intervention have been assumed into its repertoire; it has also taken full advantage of Jùjú’s apparent decline as a Yorùbá musical form.Footnote 14 Pasuma, a quintessential crossover artiste, is the very embodiment of this transition, Hence the appeal – his and Fuji’s – to Pastor Ogundipe.

These patterns, observed and analysed from a Nigerian standpoint, would seem to hold true for other African countries. Birgit Meyer, surveying Ghanaian Pentecostalism, writes:

Relatively undisturbed by the state, but all the more indebted to the emerging image economy, Pentecostalism has spread into the public sphere, disseminating signs and adopting formats not entirely of its own making and, in the process, has been taken up by popular culture. In the entanglement of religion and entertainment, new horizons of social experience have emerged, thriving on fantasy and vision and popularizing a certain mood oriented toward Pentecostalism. (Meyer Reference Meyer2003: 20)

In his work on Malawi, Van Dijk shows how Pentecostal ideology unwittingly created ‘the space to experience witchcraft in terms of mockery, laughter and amusement’ (Reference Van Dijk, Moore and Sanders2001: 99). In both countries, as in Nigeria, identified trends in the convergence of Pentecostalism and popular culture result in the further blurring of the boundaries between secular and religious entertainment. In the omnipresent shadow of commerce, the mutual interpenetration of Pentecostalism and popular culture in Nigeria steadily unfolds.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this article was presented at the panel on ‘Rethinking the Postcolony: 25 Years After’ at the twenty-seventh Biennial Conference of the African Studies Association of the United Kingdom (ASAUK), University of Birmingham, September 2018. I thank members of the panel and the audience for their comments and questions. This article uses data from field research undertaken with financial support from the Kroc Institute, University of Notre Dame. I thank James Yékú for comments on an earlier draft, and the journal’s anonymous reviewers for their comments, questions and nudges.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Ebenezer Obadare is Douglas Dillon Senior Fellow for Africa Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, Washington DC, and Research Fellow at the Institute for Theology and Religion, University of South Africa.