This article explores book publishing in Tanzania through the history of two pioneering publishing houses – and the charismatic man behind them. It results from informal conversations and interviews with Walter Bgoya, regarded as an ‘éminence grise’ and an ‘icon among African publishers’ (Zell Reference Zell1998: 104; Reference Zell2016: 1), and from discussions with two close colleagues and three authors/friends. General manager of the parastatal Tanzania Publishing House (TPH) from 1972 to 1990, renowned for Walter Rodney's How Europe Underdeveloped Africa and Issa Shivji's Class Struggles in Tanzania, in 1991 Bgoya pioneered an independent publishing model: he founded Mkuki na Nyota Publishers Ltd (known as Mkuki na Nyota), of which he is managing director, and which has issued high-quality books despite the institutionalization of austerity.

Debates on African publishing and book history have revolved around writers’ and publishers’ autonomy, international trends, copyright, the language question, textbooks and scholarly publishing, and hopes for the future (Altbach Reference Altbach1987; Kamau and Mitambo Reference Kamau and Mitambo2016; Larson Reference Larson2001; Ngobeni Reference Ngobeni2010; Van der Vlies Reference Van der Vlies2012). Important interventions have been made by scholars and publishers from the global North with an acute awareness of African constraints (Currey Reference Currey1986; Davis Reference Davis2011; Zell Reference Zell1990; Reference Zell1998; Reference Zell2016). Henry Chakava, founder of East African Educational Publishers in Nairobi, and James Tumusiime, creator of Fountain Publishers in Kampala, have addressed these issues in their autobiographies (Chakava Reference Chakava1996; Tumusiime Reference Tumusiime2014). Bgoya himself has written on many aspects of the African book sector (see, inter alia, Bgoya Reference Bgoya1986; Reference Bgoya1997; Reference Bgoya2014). These publications, which connect publishing and textual production to cultural and economic development, have mostly targeted a non-academic readership, including donors.

A different and unrelated academic scholarship on past and present African print cultures has shed light on ‘hidden’ innovators, sometimes non-literate thinkers, readers’ multiple engagements with texts, and processes informing reception, circulation and consumption (Barber Reference Barber and Barber2006; Dick Reference Dick2012; Peterson Reference Peterson2004; Peterson et al. Reference Peterson2016).Footnote 1

This article represents the first scholarly attempt to put these two bodies of work in conversation, in that it brings together a focus on Walter Bgoya as a cultural innovator (though by no means ‘obscure’), the books he has helped conceive and produce, the ‘habits and dispositions surrounding them’ (Barber Reference Barber and Barber2006: 2), and the obstacles faced by a publisher from ‘the neglected continent’ (Zell Reference Zell1990: 19). In so doing, I reconstruct and recount Bgoya's intellectual formation, aspirations and motivations to work in an exacting sector, while simultaneously investigating the inner workings of two leading publishing houses and the consequences of austerity measures on book production and dissemination in postcolonial Tanzania.

I examine these themes using the framework of resilience as an analytical tool through which we can grasp how Bgoya has responded to the challenges engendered by state policies (or the lack thereof) and the shifting world order. Resilience – in its most mundane sense the ability to adjust to adversities – changes according to the hardships, which in turn may become the normal conditions under which one operates. Bgoya's resilience is charted through the lens of microhistory, an epistemologically fruitful historiographical perspective (neither a school of thought nor an orthodoxy) that has sometimes been misunderstood: the small scale was once discarded as ‘a trap’ (Prins Reference Prins and Burke1991: 134). Yet, reducing the scale and considering apparently insignificant facts and individuals’ idiosyncratic social relations allows us to grasp continuities and clues that can generate – not automatically, and not by analogy, but by anomaly, what Edoardo Grendi once called ‘the exceptional normal’ – an appreciation of broader historical phenomena (Levi Reference Levi1990; Ginzburg Reference Ginzburg1994; Grendi Reference Grendi1994; Peltonen Reference Peltonen2001).Footnote 2 With this theoretical backdrop in place, I aim to demonstrate how concrete and intimate details about two publishing houses and the man behind them – i.e. the ‘micro’ dimensions (publishing model, individual choices, the social relations around them, entities constraining publishing) – are connected to the ‘macro’ (national and global events).

Walter Bgoya's ideology and values, innovations and risks, constraints and opportunities, as well as the strategies he deployed to handle shrinking state support, scant resources and donors’ assistance (without acquiescing to them), are discussed here with the aim of illuminating three major themes. First, through an historical account of two influential Tanzanian presses, this article fleshes out the intellectual contribution of the publisher who has been intertwined with them for fifty years, a man whose coming of age occurred in an exhilarating time of decolonization, anti-racist protests, Pan-Africanism, and debates on liberation, imperialism and Marxism in the context of the Cold War. Second, in assessing how key political, normative and financial changes have affected the production and distribution of books in postcolonial Tanzania, the article shows that the main continuities are constituted by Bgoya's close personal engagement with authors and by his sense of vocation despite constant (though never linear) austerity measures. Lastly, I argue that identifying how specific conditions of shortage have affected the printing and marketing choices made by a publisher can offer insights into the ways in which African cultural institutions have sought to favourably position themselves within (and outside) the state in a changing global context.

In showing the links between two publishing houses committed to novelty and excellence and the philosophy behind them, the article reveals how five decades of knowledge production and distribution have been based on the leftist beliefs of a man who continues to imagine himself in opposition to neoliberalism. Resilience and radicalism, articulated in Bgoya's practices and discursive strategy, point to the persistence of a radical stance into the decades of austerity; resilience thus becomes emblematic of the often overlooked continuities between the global anti-racist activism of the 1950s and 1960s, the liberation struggles and Pan-Africanism, the ethos of ujamaa, and the post-Cold War decades seemingly dominated by neoliberalism. Although Bgoya's trajectory, vision and expertise are unique, his acts of remediation expose the worldview and contribution of a generation deeply invested in intellectual freedom and progressive cultural production and dissemination.

Ideological formation

Born in Ngara (Kagera Region, Tanganyika) in 1942, Walter Bgoya attended a mission primary school and then an Anglican boarding school about 200 miles from his village. What sparked his discovery of the joy of reading were his parents’ illustrated Bible and exposure to adventure books for adolescents while being school librarian as a teenager. After completing his O levels at a government school in 1960, he won a scholarship from the African American Institute to pursue a BA degree in Political Science in the USA, and left for Kansas five months before Tanganyikan independence in December 1961. Four intense years in the USA marked his political awakening. He encountered jazz and international fiction (two lasting passions), sold books door to door, was captivated by the fervent political climate, and met exiled artists and activists from South Africa and elsewhere. The racism he experienced first hand led to his involvement in student politics, agitating for opening up segregated institutions (see Monhollon Reference Monhollon2002).

Upon completing his degree in 1965, Bgoya returned to Tanzania, a one-party state under the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU). After stints in Ngara, Kampala and Bujumbura, he settled in Kariakoo, Dar es Salaam. As part of a small network of mission-educated and politically conscious individuals, in 1966 he was offered a job in the Research Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.Footnote 3 In this period he read Marxist literature, imbibed the writings of President (and Foreign Minister) Julius K. Nyerere, joined the TANU study group, and became a member of the party after the 1967 Arusha declaration.Footnote 4

Subsequently assigned to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Africa Desk, he worked closely with the leaders of Southern African and other liberation movements, and attended the Organization of African Unity's Liberation Committee meetings in Dar es Salaam and in other African cities. In 1968, Bgoya was transferred to the Tanzanian Embassy in Addis Ababa, and in 1970 to Peking (Beijing), where he worked for six months as second secretary. However, growing uneasiness about life as a diplomat – he saw the Foreign Office as restricting his intellectual freedom – prompted him to embark on another career path. An opportunity presented itself in 1972.

TPH: the golden period of Tanzanian publishing

Tanzania Publishing House (TPH) was established in 1966 as a parastatal organization with 60 per cent share ownership held by the National Development Corporation (NDC) and 40 per cent by Macmillan Educational Publishers UK. Several newly independent African governments adopted similar paradigms: with ‘no model of publishing … to be perpetuated or improved upon’ (Brock-Utne Reference Brock-Utne1996: 179), parastatals were deemed suitable to counter foreign companies’ dominance. Thus, the first state publishing house was ironically a joint venture with a private multinational company (ibid.).

Two men shaped TPH in its early days: general manager Robert Hutchison, a left-wing Englishman, and editor Harko Bhagat, a young Zanzibari radical thinker whose involvement in the island's opposition politics alongside Abdulrahman M. Babu led to his imprisonment in 1971. Hutchison planned to return to the UK, and Macmillan slowly withdrew from TPH after losing its monopoly on educational publishing. In August 1972, Bhagat, aware that his stint in detention would prevent him from being appointed to head the company, approached Walter Bgoya, who eagerly agreed to join TPH. After undergoing training with Hutchison and at Macmillan Education in England for three months, his tenure as general manager began in 1973. He recalls having

[a] very very tough time. I was doing editing, proofreading, cover design, everything. Since there were no computers … typesetting was done on old letterpress machines (monotype and linotype) with letters cast from hot metal arranged to form lines and paragraphs. Many typesetters didn't know English, so there were many mistakes and I had to correct the proofs several times.Footnote 5

From the outset, Tanzanian publishing and printing industries were governed by a dearth of training facilities for publishers and authors and legislative and financial challenges: copyright laws and enforcement were weak; paper, inks and spare parts were subject to heavy duties and taxes.

Notwithstanding these challenges, the vibrant political and intellectual climate enabled Bgoya to expand TPH's range of publications. Dar es Salaam, which hosted the main Southern African liberation movements, was ‘an ideological centre with considerable magnetic pull, drawing liberal and radical thinkers from around the world’ (Mwakikagile Reference Mwakikagile2006: 36). With fewer diplomatic and civil service constraints, his contribution to decolonization efforts increased. Under Bgoya's directorship, TPH issued Walter Rodney's How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (Reference Rodney1972) and Issa Shivji's Tanzania: the silent class struggle (Reference Shivji1973), ground-breaking books still in a manuscript form when he joined.

Although TPH was parastatal, the government did not dictate its publications. To explain the intellectual autonomy he experienced and entrenched, Bgoya recounts that when the chairman of the TPH board attempted to stop Shivji's manuscript from being published, Hutchinson, then still general manager,

emphatically stated that we would publish it and I strongly supported that position, [so] the chairman went to inform Mwalimu Nyerere (behind our backs) and to seek his advice. In a note to the chairman, Mwalimu replied that his job was of President and the job of TPH's General Manager was to publish books; each should do his job.Footnote 6

From this episode, which Bgoya also related in writing (Reference Bgoya, Kamau and Mitambo2016: xii), one might speculate that Nyerere was pleased that TPH's publications largely coincided with the government's goals. However, Bgoya insists that TPH was truly independent in its editorial and intellectual choices, and its publications did not have to buttress Nyerere, for whom the civil service should be ‘sheltered from the interventions of politicians’ (Eckert Reference Eckert, Bierschenk and Olivier de Sardan2014: 209). While some TPH books shared broad ideological similarities with the government, Bgoya often criticized ujamaa's flaws – from a radical perspective.

He also recalls having been summoned by a minister who instructed him to publish his manuscript. When Bgoya unceremoniously refused, maintaining that it was not good enough, the minister was taken aback.

‘What do you mean? I am telling you,’ to which I replied, ‘Sorry, I am not going to do it. Your job as a minister is not to tell me what to do in my company. Being a minister does not change our relationship as author–publisher … Since TPH is state-owned you can get it published, but you have to sack me first.’ He was so stunned! He couldn't believe it.Footnote 7

Bgoya views this incident as an attempt by a government official to use his position to advance his personal interest rather than assert control over cultural production. This attitude, he explains, stemmed from the widespread tendency to see a public press as obliged ‘to publish anything’, and, more importantly, to conflate publishing and printing (see le Roux Reference le Roux and Van der Vlies2012 on South Africa). To exacerbate this misconception is the fact that

in Kiswahili -chapisha means both ‘to cause to be published’ and ‘to cause to be printed’. ‘Publish’ and ‘print’ are very close, -chapa. When I say I am a publisher [mchapishaji] … you have to explain that there is a process before going to print. [Even] Tanzanian banks are surprised when we … ask for a loan … They understand printing but not publishing!Footnote 8

In the meantime, TPH's reputation grew steadily, and, by 1975 – when Macmillan was bought out and TPH became fully owned by NDC – it had become a fulcrum of progressive ideas. The 1974 Sixth Pan-African Congress saw prominent internationalists and representatives of liberation movements from Africa and the diaspora flock to Dar es Salaam (Bgoya Reference Bgoya and Minter2007: 105). The organizing secretariat, composed of Bgoya's friends from the 1960s, often met at TPH. ‘Everybody came … There were endless discussions,’ he remembers.Footnote 9 Unable to go back to Kenya after three years in solitary confinement for a political pamphlet in 1972, Mombasa-born poet and activist Abdilatif Abdalla joined the Institute of Kiswahili Research at the University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM), where he spent seven years (see Kresse Reference Kresse2016). He met Bgoya through his Nairobi-based brother Abdilahi Nassir, then Swahili editor of Oxford University Press (OUP) in East Africa, which had a branch in Dar es Salaam (on OUP in East Africa, see Davis Reference Davis2011). Abdalla and Bgoya became friends. He recalls TPH's ‘pivotal role in African liberation … Walter's office was a meeting place for most freedom fighters.’Footnote 10

In this period, Bgoya joined the Central Committee of the TANU Youth League, which furthered his understanding of TANU's position ‘in promoting (and if necessary, even hindering) radical transformation of state and society in favour of the workers and peasants whose interests it was established to serve.’Footnote 11

He also built connections with the UDSM departments of Political Science and Development Studies. A hub of cultural ferment ‘imbued with extraordinary intellectual vigour’, UDSM was ‘greatly inspiring and influencing discourses on state and society and challenging orthodoxy’ (Bgoya Reference Bgoya2014: 116). It hosted an impressive array of scholars from Guyana, Europe, the USA and Canada, Tanzania and other parts of Africa – Walter Rodney, Clive Thomas, Terence Ranger, Giovanni Arrighi, Tamás Szentes, John Saul, Lionel Cliff, Mahmoud Mamdani, Yash Tandon, Dani W. Nabudere, Nathan M. Shamuyarira, Issa Shivji, Karim Hirji, Marjorie Mbilinyi, Penina Mlama – who at different times distinguished UDSM as a centre of radical knowledge production. Students, including a young Yoweri Museveni, published the radical magazine Cheche (‘Spark’) (Hiriji Reference Hiriji2010).

Other key developments were the adoption of Swahili as the language of instruction in primary schools, and Nyerere's national adult literacy campaign, first launched in 1970 with paper provided by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA).Footnote 12 Unprecedented in Africa, the campaign allowed TPH to publish educational books with print runs of more than 3,000 copies, a considerable number for the local market (see Kamau Reference Kamau, Kamau and Mitambo2016: 8). The healthy income enabled Bgoya to publish Agostinho Neto's Sacred Hope (Reference Neto1974), the first ever English translation and publication of the MPLA (People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola) president's poetry, launched at the State House. Shivji's Tanzania: the silent class struggle was expanded and published jointly with Heinemann as Class Struggles in Tanzania (Reference Shivji1976). Other radical publications were Samora Machel's pamphlet Establishing People's Power to Serve the Masses (Reference Machel1977), first written in Portuguese, and The Political Economy of Imperialism (Reference Nabudere1977), a critique of Shivji's book by Ugandan Pan-Africanist and political scientist Nabudere. Titles in the Political Science Series included Ann and Neva Seidman's US Multinationals in Southern Africa (Reference Seidman and Seidman1977) and Babu's African Socialism or Socialist Africa (Reference Babu1981), co-published with Zed Press (later, Zed Books).Footnote 13 Articles from UDSM's ideological debate around class struggles, the state, imperialism and liberation were edited by Ugandan political economist Yash Tandon and published by TPH with an introduction by Babu (Tandon Reference Tandon1982). TPH also released many successful children's books, major Swahili novels and plays with an initial print run of between 3,000 and 5,000, and books on scientific subjects in Swahili. By 1983 it had issued more than twenty titles in its Ufundi (‘Technical’) series. This was arguably the golden period of Tanzanian publishing.

Navigating austerity and reconfiguring TPH

By the early 1980s, a serious national crisis, exacerbated by the 1978–79 Ugandan war, precipitated the collapse of health services, education and transport, and increased the scarcity of basic consumer goods. The impact on the publishing and printing industries was dire: the East African Literature Bureau declined with the downfall of the East African Community in 1977. The largest book printing company, Printpak, experienced shortages of paper and spare parts. Binding, stitching and trimming capacities were curtailed. Lacking raw materials, ink factories ceased ink production. The National Printing Company (NPC) also suffered greatly (Bgoya Reference Bgoya1986: 20–1). In 1979, TPH was transferred to Tanzania Karatasi Associated Industries. Unable to procure paper, in 1983 Tanzania Litho – probably the best of the forty registered book printers – switched to packaging. The crisis of parastatals, the university press and independent companies was worsened by weak distribution systems and the decline of public libraries.

To limit financial stagnation, Nyerere launched the National Economic Survival Programme (1981–82) and the Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs; 1982–86), ‘self-imposed austerity measures … designed to stave off acceptance of IMF [International Monetary Fund]/World Bank policy prescriptions’ (Kaiser Reference Kaiser1996: 231). While Bgoya supported Nyerere's stand-off with the World Bank and the IMF, the economy further deteriorated. Nyerere's 1985 resignation as president was partly instigated by his rejection of these policies. The Economic Recovery Programme (ERP) adopted in 1986 by Ali Hassan Mwinyi implemented the market-oriented plans imposed by the IMF and World Bank, which earned the new president the sobriquet ‘Mzee Rukhsa’ (‘Mr Anything Goes’).Footnote 14

The government sold many deficit-ridden parastatals, which had become sites of private accumulation and corruption (Chachage Reference Chachage and Gibbon1995). Massive devaluation wiped out TPH's working capital reserves and printing costs skyrocketed. A paucity of bank loans and high interest rates (only one national bank existed under ujamaa, and interest rates often reached 40 per cent), coupled with a ‘harsh tax regime, duties on imported paper and the denial of foreign exchange allocations for machinery and other consumables’ (Bgoya Reference Bgoya1997: 17), turned TPH into a collapsing enterprise. Without government policies to cushion TPH against its losses, Bgoya and his staff did ‘whatever it took to survive’ and ‘lived on the few sales of those old books we had in stock. We were not printing new ones.’Footnote 15 To make matters worse, the Ministry of Education refused to settle a substantial debt it owed TPH from previous book purchases, which, if paid, would have given them a chance to release new titles.

Moreover, under the SAPs regime, multinationals profited from foreign aid prescriptions, muscling out local companies. The World Bank's allocation of US$60 million for school and university textbooks largely went to these companies, irrespective of the cultural relevance of the material supplied. When in 1990 the state sought to involve Tanzanian companies in textbook publishing, the East African branch of OUP was counted as a local company. Likewise, Macmillan became an African company by creating a joint venture with a Tanzanian representative. Between them, the two multinationals controlled more than 60 per cent of the textbook market. This, combined with foreign exchange constraints and an inefficient and expensive postal service, made overseas sales nearly impossible. Frustrated by his inability to advance TPH, in 1990 Bgoya left, with a gratuity of only 63,000 Tanzanian shillings (Tzsh). Although the company continued to operate, and two managers succeeded Bgoya, without an injection of government capital TPH remained incapacitated.

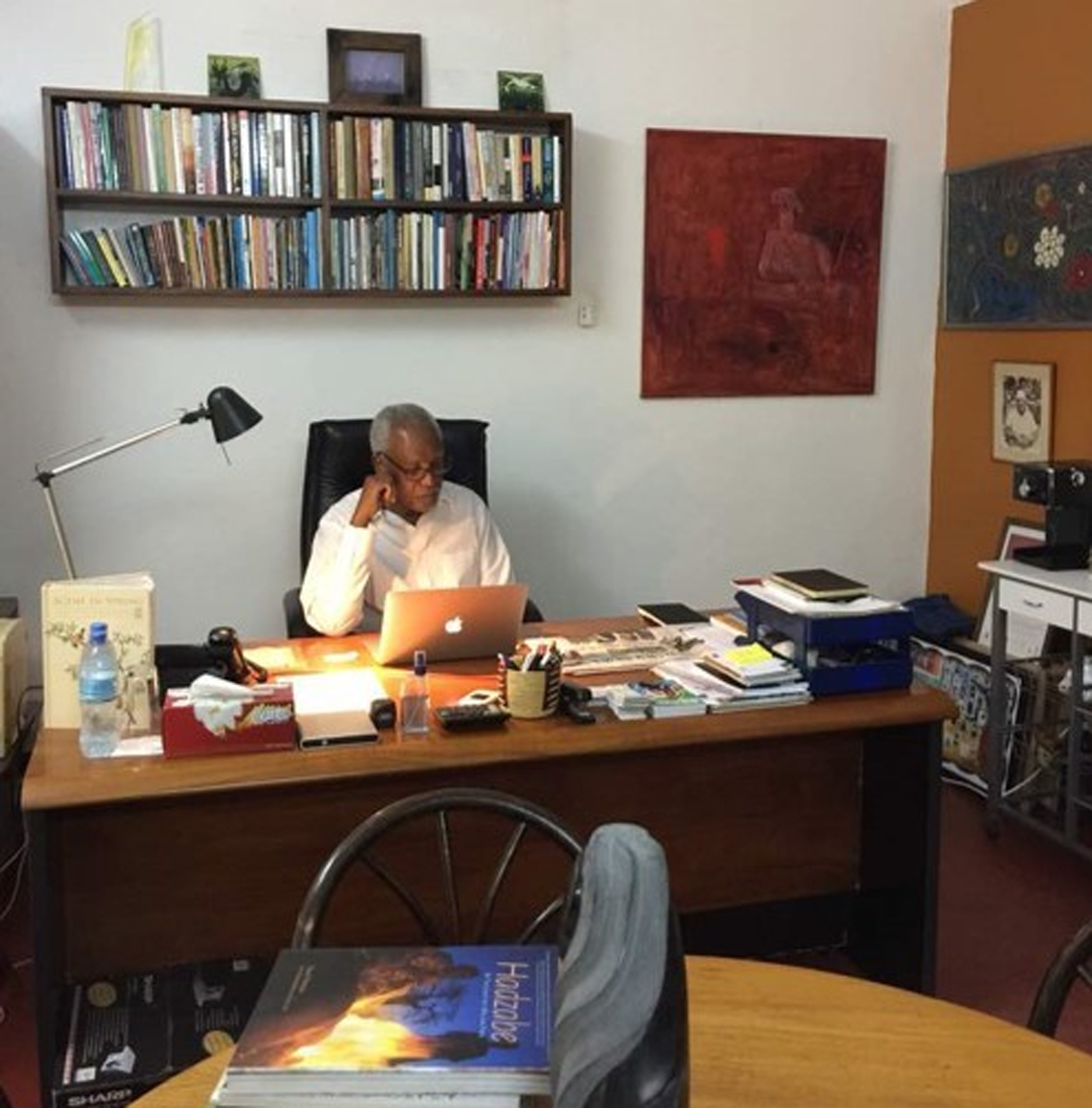

The nationwide drive to privatize parastatals (which increased during Benjamin Mkapa's presidency) also negatively affected TPH, which was earmarked for privatization through the ‘management and employee buyout’ (MEBO) model. TPH employees had no choice but to withdraw and ask Bgoya to buy the shares they had acquired as part of the privatization deal. TPH thus became a shell company of which Bgoya became the majority shareholder (81 per cent). What remained were the name and the central location. The building on Samora Avenue came to house a sister company – ‘TPH Bookshop’ – so named to take advantage of Tanzania Publishing House's popularity, but not related to it in business terms (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1 Walter Bgoya in his office, Samora Avenue, Dar es Salaam, May 2018. Photograph: Mkuki Bgoya. Source: Photograph courtesy of Mkuki Bgoya.

Figure 2 Iconic TPH on Samora Avenue, Dar es Salaam. The signboard carries the words: ‘TPH Bookshop. Since 1966. Indigenous. Independent.’ Source: Photograph courtesy of Mkuki Bgoya.

Mkuki na Nyota and Walter Bgoya's ‘guerrilla war’

In this context of institutional and budget reconfiguration, in 1991 Bgoya established his own independent company, Mkuki na Nyota (‘Spear and Star’) (MnN), a name bearing a highly symbolic meaning. The spear stands for struggle, and the star incarnates internationalism. While the initial logo depicted a Maasai warrior standing with his spear pointed towards a star, the later agile, stylized figure throwing a spear towards a star embodies ‘aspiring for the stars, pushing beyond the limits’.Footnote 16

The adjectives ‘independent’ and ‘progressive’ used by Bgoya to describe MnN require a brief explanation. ‘Progressive’ mirrors Edward Said's notion of progressive intellectuals involved in ‘the struggle for freedom, justice, [and] humanity’; thus, in postcolonial Africa, the publications emanating from a progressive press seek to further social justice (Bgoya Reference Bgoya2014: 111–12). An ‘independent’ publishing house is self-financing and is in control of editorial decisions. When I showed Walter a description of an independent press as ‘a small press, lacking substantial capital, that specializes’ in publishing ‘materials which commercial publishers reject’ (Darko-Ampem Reference Darko-Ampem2003: xi), he vehemently disagreed. ‘We don't publish what others have rejected’; most commercial publishers are only interested in books with ‘secure markets and high profitability’.Footnote 17

Notably, a similar process occurred in Kenya in 1992, where Bgoya's friend Henry Chakava – regarded by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o as the initiator of an ‘alternative model’ (Reference Kamau and Mitambo2016: 24) – bought the shares of British-owned Heinemann Kenya and founded East African Educational Publishers (EAEP), transforming a representative of a ‘filthy’ multinational into ‘an independent and successful indigenous company’, which broke ‘the myth of superiority of expatriate management’ (Bgoya Reference Bgoya, Kamau and Mitambo2016: viii–ix).

A significant early development for MnN was foreign donors’ interest in strengthening African publishing; this interest primarily came from Scandinavian countries and private institutions such as the Ford Foundation and the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation.Footnote 18 In early 1990s Africa, ‘[a]usterity's constraints on public spending led donors to a “civil society” focus in which NGOs would fill gaps in basic social services’ (Pfeiffer Reference Pfeiffer2019: 51). This somehow counterbalanced the absence of state support and SAPs’ damage to the education system.

In 1991, Bgoya was a key participant in a sponsored conference on ‘Publishing and Development in the Third World’, held in Bellagio (Italy), that identified the following problems: ‘fiscal policies (taxes, duties), state publishing monopolies, the lack of capital and trained personnel and the conduct of multilateral agencies such as the World Bank’ (Bgoya and Jay Reference Bgoya and Jay2013: 22). Its main outcome was the Bellagio Publishing Network, replaced in 2011 by the African Publishers Network (APNET), which soon became inactive due to it being heavily ‘donor dependent, operating as an NGO’ (ibid.: 23).

Partnership with the Canadian Organization for Development through Education (CODE) – which donated paper, vital amidst irregular paper supplies – generated the beneficial Children's Book Project (CBP). CBP enabled Bgoya to publish nearly eighty children's books in five years. Once manuscripts were accepted, publishers were requested to purchase 3,000 copies out of a print run of 5,000 and sell the rest commercially. Through this mechanism, which guaranteed that publishers would break even, Bgoya could venture into issuing other titles.

In a context of belt-tightening, foreign donors provided funding, facilitated regional training courses, and sponsored international book fairs, through which independent African publishers established collaborations and expanded their markets.

However, considering publishing as ‘another front in the struggle’ (Bgoya Reference Bgoya and Minter2007: 106), and partly in a bid to limit dependence on donors – which he deems ‘monsters’ – Bgoya had to find other sources of income by mobilizing local and international networks built in the years of the liberation committee and TPH. Additional income came from publications for local independent research institutions, freelance editing, commissioned writing, consultancies on media and book publishing, allowances from the membership of various boards of directors, both during the latter part of Mwinyi's presidential mandate and after Mkapa's 1995 election, and participation in the Nyerere negotiating team (1995–99) during the Burundi Peace Initiative. These activities, though time-consuming, enhanced Bgoya's management skills, raised his profile, and enlarged his networks, spawning new publishing projects. This modus operandi was not an exception:

All the [independent] publishers I know in Africa [experience this], except those … who took over from thriving multinational companies … It's in some ways phenomenal that we have been able to survive. It's a guerrilla war! … And it hasn't changed. What has changed is that we are more established and more experienced, and we can borrow from the banks, even though the interest rate is still very high – 20 to 22 per cent.Footnote 19

An unexpected factor that enabled MnN's growth was that, with SAPs, the regime of foreign exchange control was relaxed. Also, with the creation of the bureau de change, by the mid-1990s Bgoya was able to capitalize on lower printing costs in India (later China) and better quality.

Furthermore, the African Books Collective (ABC) – founded in London in 1985 and trading from Oxford since 1989 to bring African voices to the world – facilitated global marketing and distribution of African books by putting them on major bibliographic databases. This increased MnN's visibility and accessibility. Though initially supported by donors, primarily SIDA and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), ABC became self-financing in 2007. Bgoya was not only a founding member, but also its chair until 2017.

The advent of the internet was also crucial for Bgoya, who could work with skilled editors and writers overseas. Outsourcing staff and employing freelance editors abroad were partly due to the dearth of specialized institutions that trained qualified editors (the main centres are in Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa) and to Tanzanians’ poor mastery of English.

The early 2000s presented a new challenge: the demise of donors’ support stemming from the adoption of the United Nations Millennium Declaration, which listed universal access to primary education among its eight development goals, but excluded the publishing sector and did not cater for higher education and teacher training. These so-called poverty reduction strategies led to the rapid decline of the Zimbabwe International Book Fair and other key platforms for marketing books and networking.

The unstable local currency and high printing costs forced Bgoya to limit MnN's print runs. This in turn increased the cost per unit and hence the price of books, ensnaring him and other independent publishers in ‘a veritable vicious circle’.Footnote 20 As MnN's general manager explained, for a scholarly monograph the minimum quantity using offset printing is 250 copies when printed overseas and 500 copies if printed locally. While independent publishers hope to sell all the books they print in as short a time as possible and then to reprint, this rarely happens, and many books remain unsold. The publishers’ goal has been to sell enough to break even, and hopefully make some profit. When it comes to pricing books, MnN's editorial team has applied a standard industry method, varying allocations of costs and returns ‘to what the market will accept’.Footnote 21 Bgoya and his team know, for example, that it is hard to sell a Swahili novel above 15,000 Tzsh (approximately US$6). Books in social sciences cannot be priced at more than 35,000 Tzsh (US$15), while art books can be sold for 40,000 Tzsh (US$17).

While even major publishers cannot be certain about sales performance, small independent publishing houses have faced additional challenges:

We don't have resources to effectively promote our books … We don't have proper market research. I cannot [afford to] pay a top marketing person. [There is] no marketing department which would conduct a study of local, regional, African and international sales and which would build a strong database, disaggregate that into different interest groups and constituencies. For this you would need assistance; someone strong in IT, [able to] use social media effectively. [You should] give them transport; send them to [major] books fairs: Frankfurt, Cairo, Delhi, etc. … The only resources we have are for attending conferences here in Dar, and visiting universities. Nevertheless, over the years we have learned to get a feel of the market and do manage to make fair guesstimates.Footnote 22

Another persistent problem has been rampant book piracy. In one of his writings, Bgoya rails against ‘those that built their industries on pirating others’ books for ages’ (Bgoya Reference Bgoya, Kamau and Mitambo2016: xi; on piracy in Kenya, see Ouma Reference Ouma, Kamau and Mitambo2016). More recent obstacles have been the stagnant economy under President John Magufuli, and the slowing down of business due to Covid-19.Footnote 23

The backstage of publishing: setbacks and prospects

Out of forty independent publishing houses registered with the Publishers Association of Tanzania (PATA), only half are active. While about nine release new books regularly, most publish one or two books annually, or occasional brochures and pamphlets for non-commercial distribution. Since the 1990s, Tanzanian publishers, like their counterparts in other developing countries, have concentrated on the only profitable market: educational publishing.Footnote 24 Textbook publishing has undergone three phases: state publishing (1966–85), private sector publishing (1991–2012), and return to government monopoly over educational publishing in 2014, under President Jakaya Kikwete.Footnote 25 This represented a major setback for many independent companies, which were excluded from an area on which they had heavily relied since the early 1990s.

As scholar and retired UDSM associate professor in language and linguistics Saida Yahya-Othman explains: ‘[W]hat publishers used to do was to make an effort to have at least one book for schools. Once that was ensured, they had the luxury to publish other things.’ When the Tanzania Institute of Education, originally composed of curriculum developers, was tasked with handling all textbooks’ publication stages, from writing to printing and distribution, lack of expertise within the panel had dismal consequences for the textbooks’ content.Footnote 26 As Bgoya puts it:

What the government has done by this decision to be the sole publisher of textbooks is to kill all cultural publishing. Textbook publishing is presenting educational material to students according to the curriculum. Schooling provides basic reading skills. But by itself it has little impact on literacy at national level. Literacy rates, which rose exponentially during the 1970s, have plummeted … The [text]books the panel has produced have been way below standard and there have been uproars against them in parliament and everywhere … Governments don't really know the business of publishing books … Authors, editors and related staff in a publishing house are not bureaucrats and desk officers who normally function as administrators. [It has been] a disaster. [And there are] no books in schools.Footnote 27

In assessing the impact of this policy on MnN, general manager Tapiwa Muchechemera recounts that, when he was recruited in 2008, 20 per cent of MnN's publications were textbooks. Walter's idea was for Tapiwa to expand the textbook market thanks to the experience in educational publishing he had gained with Pearson in his home country, Zimbabwe, after having studied publishing in South Africa. In 2009, the government announced that schools should adopt one textbook per subject. Although this did not turn into a policy, this uncertain situation led MnN to keep its focus on children's literature, politics, law and art books instead of expanding its range of textbooks. By 2012 it had become clear that the government was heading towards monopolizing textbooks. MnN's diversification strategy reduced the negative impact that this policy would have otherwise had.Footnote 28

A favourable development was Walter's son's appointment as production manager after his return from the USA, where he had studied graphic design. Since 2009, Mkuki Bgoya's creative design has, according to Walter, ‘revolutionized the quality’ of the books.Footnote 29 In this climate of inventiveness and steady growth, Bgoya made a bold investment: the Espresso Book Machine (EBM). One of five or so on the continent, EBM was expected to eradicate high printing costs and unsold books:

If you don't have much capital, if your market is small, it doesn't make sense to print many books when you cannot sell them [and] you have to incur costs of warehousing them. [EBM] reverses completely the Gutenberg process, where you publish, print, sell … You are [first] selling and then printing the book … One could even print and sell one copy!Footnote 30

Despite the promise of print on demand (a model also embraced by ABC) using less capital, when technical glitches arose, there were no qualified maintenance engineers and no spare parts. Once a technician had to travel from New York to fix the machine, at MnN's cost. After another period of inactivity in 2018, EBM has been repaired and the personnel has become skilled at operating it.

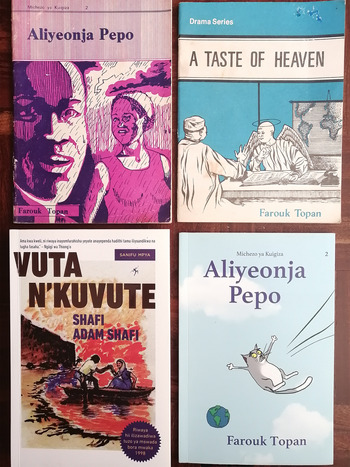

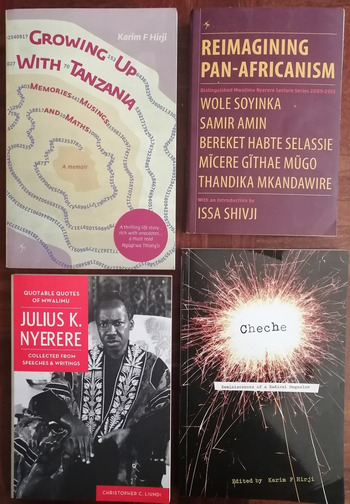

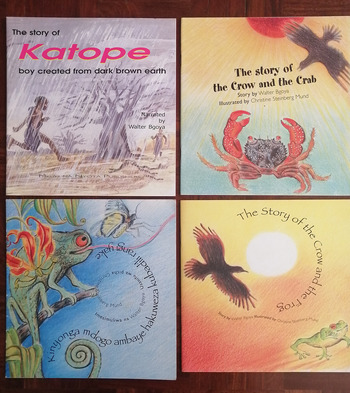

Editorial quality (paper, binding, packaging) and reasonable prices have increasingly endeared the public and local and international institutions, as well as new and established authors, including scholars from abroad. For example, historian of West Africa Toby Green published his novels Imaginary Crimes (Reference Green2013) and Colombian Roulette (Reference Green2016) with MnN. Political economy books have accounted for the majority (and the most influential) of MnN's publications – which mirrors TPH practices – followed by children's books (to date over 400, some authored and narrated by Bgoya himself), law and art books. Swahili fiction has held a special place, and several MnN novels, plays and poetry books are used in university courses on literature (see Figures 3, 4, 5 and 6). MnN's heterogeneous books, proactive search for new titles and willingness to take a risk with new authors have differed starkly from national trends. While over forty retailers sell MnN books nationwide, their interest remains mostly in textbooks. Furthermore, instead of promoting and stocking books, booksellers have customarily awaited buyers’ requests before ordering from publishers. This has affected MnN negatively.

Figure 3 Top row: Covers of TPH's fourth edition of the famous 1973 play Aliyeonja Pepo by Farouk Topan and its English translation, both published in 1980. Bottom row: MnN's covers of Shafi Adam Shafi's Vuta N'kuvute (first published in 1999) and the fifth edition of Aliyeonja Pepo, both designed by Mkuki Bgoya in 2018.

Figure 4 Four recent MnN books.

Figure 5 Four MnN children's books, two narrated and two authored by Walter Bgoya.

Figure 6 Mkuki na Nyota books displayed at TPH bookshop.

Although uneven, since 2013 the annual manuscript submission has ranged between forty-three and seventy-three, with an average of twenty-five Swahili and English books published annually. This is quite significant for an African country.

According to Yahya-Othman, the ‘terrible state’ of university bookshops and lack of bookshops of reasonable size and quality – Novel Idea in well-off Masaki ‘caters for expatriates’ – have made TPH the only place in Dar es Salaam where one can get good books. Its central location and the perception that MnN is a continuation of Tanzania Publishing House have also contributed to its popularity.Footnote 31 A recent positive development is the slow emergence of talented young authors in law and political science. Tapiwa Muchechemera, whose office is adjacent to the bookshop, where he spends quite some time – oscillating between a general manager, a bookstore manager and a bookseller – observed a gradual upward reading trend among a small but loyal group of townsmen in their late thirties. While women's interests lie in motivational writings, books on ujambazi (crime) and conspiracy theories have gained traction among the youth – provided the price does not exceed 15,000 Tzsh (approximately US$6). Evarist Chahali's Reference Chahali2016 novel Shushushu (‘Intelligence officer’) sold handsomely. Despite less spending money, the ‘hot political climate’ under Magufuli generated renewed interest in reading, even though this is mostly limited to ‘anti-establishment’ fiction.Footnote 32

Poor reading culture versus strong personal engagement

MnN aims ‘to encourage and develop a culture of reading in Tanzania’ and nurture ‘indigenous literature as a method of preserving and sharing stories’.Footnote 33 Its mission statement is ‘Relevant Books, Affordable Books, and Beautiful Books’, and it is committed to:

setting quality standards in book publishing; stimulating educational development; scouting for and nurturing both budding and established authors so as to develop Tanzanian and East African literature; providing value for money by listening to our customers and satisfying their needs for relevant, diverse, and affordable content; professionalism, transparency, fairness and integrity in our interaction with … readers, artists, designers, printers, government departments and booksellers; recognizing, encouraging and rewarding creativity by our staff in product development … and other ways of growing the business; providing our staff with opportunities to develop their skills and to take pride and responsibility for the success of the company.Footnote 34

For Muchechemera, an emphasis on nurturing may sound naïve in a country with inadequate schooling and language policies, an absence of well-equipped libraries, and ‘a big population but an unmatching appetite for books’.Footnote 35 Bgoya attributes the decline of the once rich fiction writing (in contrast to Kenya's growing book market in Swahili and English) to an education system that does not value literature. People ‘don't want anything to do with books, and after school or university they throw them away or sell them’.Footnote 36

Despite these constraints, for Bgoya, publishing should stimulate positive reading habits and answer ‘the needs of a liberating education and culture’ (Bgoya Reference Bgoya2017: 16). Reflecting on what role African publishers should play, he emphasizes that knowledge production is intertwined with dissemination:

Books influence public opinion. Books influence culture. Publishing becomes a culture itself. The culture of reading depends very much on the culture of publishing; and vice versa … Some of the books I have published have become important in raising an appreciation of creative writing. Novels, poetry, and … books on politics contribute to debate in the country … This role is the same all over the world … But publishing cannot thrive properly without developing a reading culture. And a reading culture cannot develop if the institutions, the parents … don't have access to interesting books and communities don't have libraries.Footnote 37

Walter Bgoya has been much more than a conventional publisher. While at TPH he employed two editors, when he founded MnN he put in place a standard peer-review process for scholarly books, but chose not to use external readers and editors for most works of fiction, his passion. Both at TPH and at MnN, Bgoya has encouraged writers to enhance their style and skills through lengthy discussions and advice, including reading suggestions. This has generated long-lasting friendships with authors and successful novels such as Shafi Adam Shafi's Kasri ya Mwinyi Fuad and Vuta N'kuvute, published respectively with TPH (Reference Shafi1978) and MnN (Reference Shafi1999), both results of Bgoya's close involvement in the publishing process, from giving authors lengthy feedback to providing reading suggestions. A similar point has been made for Henry Chakava, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o's editor and friend since the 1970s (Kamau Reference Kamau, Kamau and Mitambo2016: 4; Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o Reference Kamau and Mitambo2016: 21–2). In Bgoya's words:

What I do is not just a job: it's an engagement … You see what I have been telling you all the time: I engage with the authors … I spend time reading, interrogating, discussing with the authors: the characters, the plot, etc. Authors begin to see new dimensions, inconsistencies, or unclear sequencing of events. I work closely with the author. I am interested in having a dialogue … It's a relationship that develops: the closer the better.Footnote 38

Constant mediation between author and text represents a continuity between TPH and MnN. As a fellow publisher later confessed to him, aware of Bgoya's engagement, other publishers went as far as to advise writers to submit their manuscripts to TPH, get meticulous feedback, then withdraw and ‘come back to them’.Footnote 39 Asked to identify the most significant continuities in his publishing methods, Walter said:

A combination of things: no politician has interfered with my work. I have maintained my ideas of what I should publish … ‘Relevant books, affordable books, and beautiful books.’ By relevant I mean: I am not an advocate of capitalism, so it's very difficult for me to publish books by some right-winger … At the same time I am open to accepting critical books – even of socialism … You have a worldview as a publisher. It informs what kind of books you select.Footnote 40

Although Bgoya's ideology, modus operandi and vocabulary might sound old-fashioned and utopian, many authors have chosen MnN because of his communication skills and editorial advice – and sometimes precisely because of his worldview. For example, when CODESRIA commissioned Saida Yahya-Othman to edit a collection of essays by her late husband, the radical Zanzibari intellectual Haroub Othman (Yahya-Othman Reference Yahya-Othman2014), more than forty years of acquaintance with Bgoya and their like-minded outlooks determined her choice to co-publish with MnN:

Walter has a certain perspective, a ‘leftist’ perspective. I am sympathetic to his effort to get books which are meaningful [and] accessible to ordinary people – although many are in English … [He also publishes] good books, [in terms of] quality [and] content. He is trying very hard.Footnote 41

Abdilatif Abdalla, ‘one of the most renowned living Swahili poets’ (Kresse Reference Kresse2016: 6), has advised Bgoya on several Swahili manuscripts since the 1970s, has edited an anthology on two poets from Pemba for MnN (Abdalla Reference Abdalla2011), and plans to release some of his own poems with MnN:

We consider each other as brothers … We share socialist-inclined, anti-imperialist and Pan-Africanist beliefs … Walter is very much interested in ideas, in disseminating knowledge; publishing is a privileged [way of achieving that] … Those who experienced colonialism and later became [politically] active tend to do something which will continue the struggle. Walter is partly driven by that. He feels that what he is doing is a continuation of the struggle. Publishing is his contribution towards that … If he were not resilient and committed, he would have given up [on publishing] a long time ago.Footnote 42

Issa Shivji, acclaimed scholar and Professor Emeritus at UDSM, where he has held the Julius Nyerere Chair in Pan-African Studies, released Pan-Africanism or Pragmatism? Lessons of Tanganyika–Zanzibar union with MnN (Shivji Reference Shivji2008), his second major interaction with Bgoya the publisher decades after getting out Class Struggles with TPH. His choice of MnN was deliberate, even though Shivji's international standing would have granted him easy access to foreign publishers. Likewise, releasing Development as Rebellion: a biography of Julius Nyerere – co-authored with Saida Yahya-Othman and Ng'wanza Kamata – with MnN was a conscious decision (Shivji et al. Reference Shivji2020). Distributed worldwide by ABC, Bgoya's latest ambitious three-volume project had a long gestation and saw sustained intellectual exchanges with the three authors and comrades. Shivji says:

Walter worked very closely with us throughout the process, not only because he was interviewed for the book, but because he and [his son] Mkuki went out of their way to make sure that the publication was of high quality … It was … exceptional … [Also] in its design [and] layout.Footnote 43

In this process, Shivji and Bgoya, who share similar political traditions, ‘came close together on many issues’ and saw their ‘interests coincide’. As Shivji explains:

Walter has tried hard to … publish progressive work; at the same time he has to make ends meet: the two things don't necessarily work well together … Yet he remains committed to the dissemination of knowledge: if he was just purely motivated by profit, he would have moved [away from publishing] a long time ago … He can be broadly described as … [a] left-wing publisher … They find it very difficult to continue to exist … Neoliberalism is a direct attack on leftist ideology.Footnote 44

Bgoya's overall assessment of thirty years of independent publishing is that the tough conditions under which MnN has operated and the relatively small public appreciating literature have never prevented him from getting enthusiastically involved in new projects. He regards himself as strongly committed to his job; he aspires to publish more titles, attend more book fairs and international conferences, and convert the books published over fifty years into digital-based material, which is extremely pricey.

A phenomenal endeavour

Drawing from two distinct bodies of work in publishing studies and African print cultures, and using the framework of resilience and the lens of microhistory, this article has examined the glory and collapse of TPH, the practices, difficulties and achievements of MnN, and how Walter Bgoya – the central figure behind these two publishing houses, whose career in the publishing sector spans five decades – has navigated the shifting and uncertain conditions of austerity. It has illuminated the links between the backstage of publishing and the lifelong ideas of a cultural innovator whose worldview, which was shaped in a time of decolonization and Pan-Africanism, still influences his deep investment in intellectual freedom.

With the ‘age of austerity’ inaugurated in the mid-1970s, the demise of ujamaa and TPH's decline, the key adversities were the contraction of the public sector, SAPs, few and inefficient outlets, undercapitalization vis-à-vis escalating printing costs, ambiguous language policies and copyright laws, book piracy, low income and a dwindling reading culture, competition from multinationals, donors’ interventions often clashing with local realities, their sudden withdrawal after the UN's Millennium Development Goals, and limited resources to strengthen distribution networks. More recent constraints have been the government's monopoly on textbooks and financial stagnation resulting in less cash.

Running an independent company while holding on to the intellectual project that had animated TPH required Bgoya to operate in a terrain in which his cherished ideology was continuously challenged. Faced with new obstacles, in the 1990s he had to accept donors’ patronage, find additional sources of income, outsource external editors and print abroad. He has had to admit that the SAPs, though ideologically and financially deleterious, opened up unexpected commercial benefits. And the global distribution of MnN's books has occurred through ABC, which, albeit self-financing since 2007, was previously funded by donors.

In a bid to curb donors’ interference and mitigate local setbacks, Bgoya has had to constantly devise new strategies to generate revenue. Far from being ‘neutral’, these strategies have been informed by his political stance. Enhancing his own local and international status by tapping into existing networks and creating and sustaining new connections, he was able to gain the bargaining power necessary to produce and disseminate relevant, progressive and beautiful books, either written by African authors or on African matters, at a reasonable price. Increasing commercial textbook production (a plan that had to be relinquished) made it possible to produce other publications. Purchasing the expensive EBM machine, with its promise to reverse the Gutenberg process, was a way to circumvent the ‘vicious circle’ of high printing costs and produce commercially sustainable books. In seeking to maintain quality and innovation, Bgoya has spearheaded an uncommon intellectual, social and cultural mission: publishing should positively shape the local and global readership.

Despite changing times and conditions of austerity, his career has been underpinned by significant continuities, such as the passionate and unyielding pursuit of intellectual autonomy, social justice and Pan-Africanist principles – reminiscent of ujamaa's ethos. The resiliency paradigm not only is visible in his fierce and boisterous verbal reiteration of the integrity of indigenous publishing – seen as a ‘guerrilla war’ and ‘another front in the struggle’; production and dissemination of knowledge as ‘liberating’; multinationals as ‘filthy’; donors as ‘monsters’ – but is also founded on the tangible rejection of hegemony. Bgoya has thus been able to turn potentially fraught collaborations with the global North into equal power relations.

The article has also foregrounded this publisher's ability to nurture personal relationships and his close engagement with authors during the various stages of manuscript preparation, from character development (for fiction) to the editorial process. This has elicited admiration from progressive intellectuals and a niche public.

While Walter Bgoya's personality, engagement, vision and achievements are distinctive, the challenges he has encountered are not unique to Tanzania. The example of Henry Chakava, though not expanded upon, has suggested that these friends and colleagues, driven by a shared ‘nationalist and Pan-Africanist dream’ (Bgoya Reference Bgoya, Kamau and Mitambo2016: xiii), initiated similar publishing models and faced common obstacles. Their worldview is encapsulated in this statement attributed to Chakava: ‘It is … the contribution … to the academic and cultural welfare of your society that will be remembered’ (ibid.: xi).

Lastly, by looking behind the scenes and offering an intimate account of one of the continent's leading publishers, the article has shown that the core values and ethos of earlier decades have survived austerity. It has brought to light the intellectual, literary and strategic endurance of the radical politics of a generation of ‘non-aligned’ thinkers that coalesce around similar cultural and political concerns. This history provides a window into the intellectual contribution and resilience of independent cultural producers and institutions in postcolonial Africa, and complicates the pervasive tendencies to stress ruptures such as the decline of Pan-Africanism and internationalism in the face of austerity and neoliberalism.

Acknowledgements

I am hugely indebted to Walter Bgoya for the engaging conversations over the years and for his comments on two earlier drafts. I thank the National Research Foundation (NRF, grant number 90767) for financial support that enabled several research visits to Tanzania.