Carnality and spirituality: ‘the triple Ps of Zimbabwe’

… the postcolony is a world of anxious virility. (Mbembe Reference Mbembe1992: 9)

In early 2014, Zimbabwe’s public sphere was seized by tabloid-style rumours about precarious virilities, involving the former prime minister, Morgan Tsvangirai, and the ‘miracle-working’ Pentecostal prophet Emmanuel Makandiwa. Regarding the former, Elizabeth Macheka, the estranged wife of Tsvangirai, the presidential candidate of the Movement for Democratic Change–Tsvangirai (MDC-T), ‘confirmed’ to The Herald that she was separated from him because of ‘sensitive personal issues’ (Maodza Reference Maodza2014) that only the couple could resolve. Her statement was a ‘confirmation’ of an issue the public had ‘known’ and what the newspaper described, rather delicately, as ‘a medical one’. The public jumped to the conclusion that the former prime minister was suffering from ‘erectile dysfunctional disorder’ – journalist and blogger Fungai Machirori would describe this in her interesting essay ‘Of penises, politics and Pentecostalism in Zimbabwe’ (subsequently, ‘the triple Ps of Zimbabwe’) as ‘an exposé of trouble in the un-paradise that is Tsvangirai’s love life’ (Reference Machirori2014).Footnote 1 Macheka was reported to have left her marital home while Tsvangirai was in Lagos visiting the (in)famous Nigerian megastar prophet T. B. Joshua, ostensibly for a spiritual cure for his double jeopardy: political and carnal virility.

As for Makandiwa, the founder of the popular United Family International Church (UFIC), it was reported that he had performed, at the New Year’s Day service, a penis-enhancing miracle on a Namibian, whose private member was the size of a two-year-old’s. The Namibian reportedly could not sustain his love life or find a wife because of his phallic deficiency. The prophet was said to have commanded the man’s infantile private member, ‘First month grow, second month grow, third month grow, fourth month grow, fifth month ummm stop.’ The speculation was that the organ must have grown exponentially until the prophet decreed it to stop.Footnote 2

In reflecting on ‘the triple Ps of Zimbabwe’ – a subject that ‘enthralled’ ‘the general Zimbabwean populace’ – and despite Tsvangirai’s reassurance that he had no problem with his private member, Machirori stated:

As [the] prospects for political change continue to decline, it is the rise of Pentecostalism and tales of the supernatural that seem to have filled the void in the collective imagination of most Zimbabweans … While a penis-enlarging miracle might seem like child’s play … it does epitomise the vulnerability of so many Zimbabweans who remain desperate for a change in their personal fortunes. Desperate for hope; for at least one pleasure, one relief. And the commonality of the desperation is compounded by Tsvangirai’s pursuit of the same from TB Joshua. (Machirori Reference Machirori2014)

In a striking lay sociological reflection, Machirori concluded as follows:

Just think about Tsvangirai’s case a bit more deeply, if you will. Here is a man, aged 61, married as many times as he has lost in his bid to become Zimbabwe’s elected president (three), who makes a trek to a death-predicting spiritual leaderFootnote 3 in pursuit of answers and solutions to the problems beleaguering his personal and political aspirations. In a continuation of the comedy of errors that is his love life, he returns home to find his wife gone and, a few weeks later, speculations about his impotence all over the media. (Machirori Reference Machirori2014)

If such titillating tales of phallic inadequacies were not tragic reflections of everyday life and the nature of power in the postcolony, they would have been significant simply for the hilarity they provoked – except that, as Achille Mbembe has argued, the affinity between carnality and hilarity in postcolonial contexts is not a mere laughing matter,Footnote 4 notwithstanding the fact that ‘obsession with orifices, odours and genital organs … dominate … popular laughter’ (Mbembe Reference Mbembe1992: 6). But because obscenity, such as described above – and the related grotesquery – is not exclusively the province of ordinary people (‘non-official cultures’), as Bakhtin (Reference Bakhtin1970) assumed, we need to pay greater attention to the ways in which obscenity can help explain the nature of power in the postcolony, wherever we find it among the dominant (in ‘official cultures’) – but particularly in the mutuality between ‘official’ and ‘non-official’ cultures. This is because, as Mbembe suggests, obscenity and grotesquery are essential characteristics of postcolonial regimes of domination and subordination – and subjection.Footnote 5 There is an expectation, among both the dominant and the dominated, that the (African) man of power must display or exhibit his virility – particularly sexual virility.Footnote 6 Tsvangirai’s dilemma – what Mbembe calls, in the nugget above, ‘anxious virility’ – was unlike that of ‘The Providential Guide’ in Sony Lab’ou Tansi’s Life and a Half,Footnote 7 which Mbembe cites, who had suffered ‘a nasty blow from below’ due to old age but remained, despite his ‘momentary impotence’, ‘a dignified male, still even a male who could perform’ (Tansi 2011 [1979]: 42, cited in Mbembe Reference Mbembe1992: 6). The ex-prime minister was believed to have suffered long-term impotence. Beyond the fact that obscenity is a key characteristic of postcolonial regimes of domination and subordination, Mbembe argues that particular instances of such manifestations constitute ‘active statements about the human condition, and as such contribute integrally to the making of political culture in the postcolony’ (ibid.: 7).

Against this backdrop, I reflect on Mbembe’s particular emphasis on what I call the carnality of power: that is, power’s ability to (over-)carnalize political and social relations – which, therefore, makes carnality ‘vital to understanding the dynamics of power’ (Povinelli Reference Povinelli2012: 79), and, by doing so, reduces the polis to the ‘equivalent [of] a community of men’ (société des hommes) whose ‘psychic life is organized around a particular event: the swelling of the virile organ, the experience of turgescence’ (Mbembe Reference Mbembe2006: 163). In reflecting on Mbembe’s famous essay, I intend to accomplish three interrelated goals to reinterpret the essay on the carnality of commandement: (1) by extending its reach to contemporary times, noting its persistent value in accounting for the meshing of licit and illicit sexuality as part of the licences of power in the postcolony (and beyond); (2) by extending its reach to include homosexual relationships – which Mbembe did not emphasize and which, since the original essay was published, have been largely removed from under the cloak of silence in public discourse in many parts of the continent; and (3) by challenging Mbembe’s assumption that those who laugh during instances of power’s excess and buffoonery (particularly in the context of its carnality) are laughing with and not laughing at power.Footnote 8

Why is carnality relevant for reflecting on powerFootnote 9 – and viceversa? In ‘Provisional notes’, Mbembe provides some key reasons that I reflect on in this article. Generally, ‘Provisional notes’ provides us not only with important means to reflect on the ways in which power literally penetrates the body, but also with the social and political implications of the ways in which the physical body (the carnal) and its (ab)uses are connected to the body politic. Here, I use the carnality of power to emphasize how power is instantiated by sex and sexual relations through attempts at, or actual instances of, copulation – precarious and unsolicited or desired and demanded – that are determined by relations of domination.Footnote 10 Within a distinctive economy of desire and pleasure, which Jean-François Lyotard describes as ‘libidinal economy’ (1993 [1974]), carnal power habitually involves all-consuming and relentless efforts by the dominant to gain ‘unfettered sexual access’ (Stoler Reference Stoler2010 [2002]: xxii). While some scholars, such as Stoler (ibid.), approach carnality as a phenomenon that ‘extend[s] beyond [relationships] grounded in sex’,Footnote 11 in this article I focus only on relationships grounded in sex, particularly as dictated by the dominant person’s constant thirst for sexualized bodies – and, of course, within specific formations of erotic economy (see Obadare Reference Obadare2020), including the ways in which the allure and ardour of power held by the dominant also foster erotic desires among the dominated.Footnote 12 The nature of this thirst often implies that this form of carnality would prompt violations of norms (of decency, for instance), rules and even laws, given that it is based fundamentally on unequal power.Footnote 13 This is partly a consequence of the fact that power revels in infringements of the carnal autonomy or integrity of its targets. As a result, carnal power Footnote 14 invites a surplus of rumours, gossip and suppositions about its complexion, aggression and transgressions.

I should clarify that by ‘power’ I do not mean the multidimensional leverage held and pressed into their own service only by those who are well placed in one way or another in the contemporary postcolony. I mean it, in the Foucauldian sense,Footnote 15 as a strategy that is present in all spheres of social life, mobilized by both the dominant and the dominated, and in which the two are mutually complicit (Clegg etal. Reference Clegg, Courpasson and Phillips2006: 254), as well as in the Mbembian sense as a phenomenon involving ‘the nature of [both] domination and subordination’ (Mbembe Reference Mbembe1992: 4).

I focus on the carnality of power – or the carnal life of power – for a number of related reasons. One, I want to re-emphasize some critical perspectives in ‘Provisional notes’. The first of these is Mbembe’s characterization of the postcolony as a formation marked ‘by a tendency to excess and a lack of proportion’ (Reference Mbembe1992: 3). This is important because, while things have changed significantly in Africanist scholarshipFootnote 16 since Mbembe’s essay was published, the literature, in my view, still has not paid sufficient attention to the examination of the dilemmas and challenges of ‘regular’ politics on the continent through the lens of sexual excess – including the political (as well as social, cultural and economic) implications or consequences of lechery in high places. The second is the author’s stress on the implications of ‘illicit cohabitation’ – the sharing of ‘the same living space’ by commandement and its ‘subjects’ – which, among other effects, leads to ‘mutual zombification’ (ibid.: 4). Thus, even while condemning or pretending to condemn the ‘moral lapses’ of the dominant, the dominated contribute directly or vicariously to promoting the criticality, if not the supremacy, of male virility in the contemporary postcolony by being in awe of it and/or by taking its transgressions for granted, and thus, implicitly or explicitly, cojoining (phallic) power and sexual potency. A man (especially a significant man) is expected to use his ‘maleness well’Footnote 17 – even when he does so in improper or corrupt ways in the context of the discharge of his formal duties. For instance, in Togo, President Gnassingbé Eyadéma’s political as well as phallic power were captured in the popular description of him as the ‘husband of all husbands’ (Toulabor Reference Toulabor1994: 63). Thus, a man (especially a man in/of power, such as Tsvangirai) who either lacks maleness or fails to use it well is regarded by the dominant as well as by the dominated as effeminate – that is, not a proper man.Footnote 18 The popular circulation of the social legitimacy and licence of sexual power, therefore, often means that, in what Jean-François Lyotard (1993 [1974]: 5) describes as ‘the accountancy in libidinal matters’,Footnote 19 the balance sheet is almost always resolved in favour of the powerful, particularly the most powerful.

Further, as hinted above, a focus on this aspect of the ‘system of signs’, in what Mbembe describes as the concurrent ‘chaotic plurality’ and ‘internal coherence’ of the postcolony, reminds us of the need to expand the examination of the ‘under-neath’ of things, especially those that existing social ‘strategies of concealment’ (Ferme Reference Ferme2001: 1) prevent scholars from fully accessing, as well as those that we, as scholars, often avert our gaze from because they seem too lurid or prurientFootnote 20 for (‘elevated’ and ‘elevating’) social analysis.

Starting with ‘Provisional notes on the postcolony’, Mbembe has shown that the order of things in the postcolony sometimes only makes sense when we consider them alongside the under of things. Again, as he demonstrates in this important essay, African writers have never shied away from using the carnal to illustrate the realities of social life on the continent – with Sony Lab’ou Tansi as a good example. Against this backdrop, I want to show that, contrary to some of the criticisms that the author, in the ‘Provisional notes’, is unnecessarily ‘prurient’ in his analysis of the sex and sexuality of powerful men and the targets of their erotic interests, he was in fact not only encouraging Africanist scholarship to boldly engage in and with actually existing erotic relations – including in their lurid excess and abjection – but also forcing us to focus on such matters that were elided in different ways (such as through euphemisms, metaphors, etc.)Footnote 21 both in actual social life in Africa and in the scholarly literature that described this social life. Perhaps one of the reasons why Africanist scholars, before Mbembe’s important essay, shied away from engaging with such matters was because of what Ann Laura Stoler (Reference Stoler2010 [2002]: xv) describes as the ‘inaccessibility’ of ‘people’s affective and moral states’, although these states constitute ‘critical markers of [potentially] dangerous interior sensibilities in the arts of governance’. It is therefore significant that, since Mbembe’s piece was published, there has been a noticeable eagerness among a few scholars to embrace the discussion of rumoured and/or actual sexual encounters among the dominant and between the dominant and the dominated that have consequences for the ‘dramaturgy of power’ in Africa (for example, see Piot Reference Piot2010).Footnote 22 No doubt, ‘Provisional notes’ was one of the first scholarly African works in the second half of the twentieth century to encourage us to reckon with the fact that sex and sexuality, being matters of ‘concern, surveillance and control’, as Foucault (Reference Foucault and Gordon1980: 57) describes it, can be ‘object[s] of analysis’ – particularly in the lurid way in which they are (mis)used in the postcolony.

Finally, I hope to use this reinterpretation of Mbembe to dismiss one of the ‘unhelpful oppositions’ in Africanist scholarship in the era in which he published the essay – which he failed to mention specifically – between licit and illicit sexuality.Footnote 23 This is partly because the carnal practices examined here, following Mbembe, are not ‘aberrant, exceptional excesses’ (Stoler Reference Stoler2010 [2002]: xvii) of domination in the postcolony; rather, they are common and recurrent, and therefore provide the grist for quotidian operations of power.

On the whole, Mbembe alerts us to how the dominated approve and at the same time disapprove of the sexual liaisons of the dominant; in fact, they expect that men of power must also possess sexual power, which can be – should be, and in some cases must be – staged or displayed in a number of ways, including the licentious. The more power those who are dominant have, the more tolerant are the dominated of their licentiousness – as the example of Donald Trump and his millions of worshippers in the ur-postcolony, the USA,Footnote 24 reminds us.

Paramours and paramountcy

[T]he acerbic [politician] Jonathan Moyo famously wrote that [Prime Minister] Tsvangirai approaches every issue with a shut mind and every woman with an open zip. (Gappah Reference Gappah2012)

The emphasis on orifices and protuberances has to be understood in relation to two factors especially. The first derives from the fact that the commandement in the postcolony has a marked taste for lecherous living. (Mbembe Reference Mbembe1992: 6)

In 2012, as Tsvangirai struggled to wind up President Robert Mugabe’s seemingly interminable reign in order to become Zimbabwe’s second president, The Guardian in the UK published an important piece about him. In the story entitled ‘Morgan Tsvangirai’s messy love life is a gift to his enemies’, after listing the prime minister’s many marriages and dalliances, the paper commented:

But how much does all this matter? For the most part, Zimbabweans don’t particularly care about the private lives of politicians. President Mugabe and his wife Grace began their relationship with an affair when both were married to other partners. Cabinet ministers routinely jump in and out of multiple beds, and Zimbabwe gives a collective shrug. This debacle matters for different reasons. It raises, once again, questions about the prime minister’s judgment and fitness for office. Even his allies are lining up to speak out. The Independent, a leading business weekly, asked the question: is he fit to govern, while veteran journalist Geoff Nyarota encouraged Tsvangirai to have regard for the dignity of his office. Certainly, his multiple, and, apparently, simultaneous, sexual relationships with partners who appear to have been subject to no vetting not only demonstrates his extremely poor judgment, they also raise security concerns. He has made it woefully easy for his enemies to portray him as a sex-crazed maniac. (Gappah Reference Gappah2012, emphasis added in italics)

This story exemplifies Mbembe’s point about the paradox in the attitudes of both the dominant and the dominated to the carnality of power. The dominated are appalled by the sexual excesses of the dominant when they are revealed and at the same time applaud, tolerate, ignore and/or understand them – including joking about them. Thus, resistance and passivity, autonomy and subjection constitute concurrent rather than distinct responses to carnal domination. Consequently, the banality of power is particularly expressive in the way in which people would sometimes ‘travesty the metaphors meant to glory state power’ (Mbembe Reference Mbembe1992: 6) by deploying words and phrases that carnalize power in (dis)praise of the supreme leader.

In the different types of reaction to the carnality of power, what is important is the way in which these reactions hint at or capture people’s reflections on power in the postcolony. The fact that the laughter provoked by the carnality of power suggests a certain popular ambivalence about the weaponization of the private member of those who are dominant does not provide us with the material to predict resistance or passivity. Rather, it furnishes us with evidence of the prevailing cultural attitudes that constitute useful subtexts to the discourses as well as the struggles for power. This is why the irony of particular instances of the concurrent praise and censure of carnal power through humour, pace Mbembe, should attract greater social analysis in the postcolony.

Of Zuma and Zapiro: carnality and hilarity

[T]he body in question is firstly a body that eats and drinks, and secondly a body that is open – in both ways. Hence the significance given to orifices and the central part they play in people’s political humour. (Mbembe Reference Mbembe1992: 7)

A controversial cartoon in the Johannesburg Sunday Times of 7 September 2008 by South Africa’s award-winning cartoonist Zapiro (real name Jonathan Shapiro) (Figure 1) caused an uproar and placed the cartoonist ‘in the firing line’ (Van Hoorn Reference Van Hoorn2008). In the cartoon, popularly called ‘Rape of Lady Justice’, African National Congress (ANC) leader Jacob Zuma loosens his trousers while his political allies hold down a woman wearing a sash saying ‘Justice System’, with her scales on the floor beside her. The Zuma allies include Julius Malema (then the leader of the ANC Youth League), Gwede Mantashe (one of the key leaders of the ANC), Blade Nzimande (the general secretary of the South African Communist Party or SACP) and Zwelinzima Vavi (general secretary of the Congress of South African Trade Unions or COSATU). Mantashe says to Zuma: ‘Go for it boss!’

Figure 1. ‘Rape of Lady Justice’ – Zapiro’s controversial cartoon. © 2008–2017 Zapiro. Republished with permission. For more Zapiro cartoons, visit <https://www.zapiro.com/>.

There is hardly a more apt or more popular demonstration of what Mbembe, in the epigram above, describes as ‘the significance given to orifices and the central part they play in people’s political humour’ in the postcolony than this cartoon.Footnote 25 Acknowledging the ‘massive reaction’ to the cartoon, both laudatory and condemnatory, Zapiro told the Mail & Guardian Online that this was ‘[p]erhaps the biggest reaction ever in the shortest space of time’ (Van Hoorn Reference Van Hoorn2008). The ANC, SACP and ANC Youth League not only dismissed the cartoon as ‘disgusting’ and one that ‘borders on defamation of character’, they reported the cartoonist to the South African Human Rights Commission, accusing him of ‘hate speech’. Zuma also sued Zapiro for £700,000 (Laing Reference Laing2010) but later withdrew the case. What gives rise to such conflict as this over a cartoon, argues Mbembe, ‘is not the … reference to the genitals of the men in power but rather the way in which people by their laughter kidnap power and force it, as if by accident, to examine its own vulgarity’ (Mbembe Reference Mbembe1992: 8).

Many praised the cartoon for capturing the spirit of ‘the rape of institutions’ – particularly the justice system. ‘He [Zuma] is raping the justice system,’ adds Zapiro, ‘and they [Zuma’s political allies] are complicit in that’ (Van Hoorn Reference Van Hoorn2008). Perhaps what made the cartoon more hilarious for some and more hideous for others was that Zuma had faced trial for rape. Therefore, in this case, while Zapiro insisted that rape was a metaphor for what Zuma and his constituents were doing to the justice system, Zuma and his supporters saw this cartoon as constituting a literal accusation of rape – although Zuma had been acquitted two years earlier (see Hammett Reference Hammett2010).Footnote 26 The reactions that this cartoon elicited again demonstrate the attitude of many people to what is often regarded as an issue of male virility – even in grave circumstances of rape allegations. Pierre de Vos, a constitutional law professor at the University of Western Cape, ordinarily a ‘great fan’ of Zapiro, wondered if the cartoon was not ‘immoral and ethically deeply problematic’ and ‘asked whether Shapiro was undermining respect for the judiciary he was purportedly defending, by suggesting subliminally that Zuma should have been convicted in the rape trial’. He also suggested that Zapiro might be ‘“cheapening” the horror of the act [rape] and helping to desensitise people’ (SAPA 2008, emphasis added). But many people disagreed with de Vos, with one stating: ‘It is time someone drew attention to the shocking behaviour of these political figureheads and their most avid supporters’ (ibid.).

Indeed, the sketch seems to condense the long-running public discourses of lechery around Zuma. As a polygamist, he had not only married six times and had at least three wives at a certain point during his presidency (three by official accounts, more in public discourse),Footnote 27 he allegedly had between twenty and twenty-two children from his spouses and other lovers (Head Reference Head2017) and was often reported to have had sex with other women. Thus, in the estimation of his critics, despite having been acquitted of the charge of having raped his friend’s daughter, Zuma’s image as a libidinous leader festered. The woman he was acquitted of raping was an HIV-positive AIDS activist. Zuma, who claimed that the sex was consensual, admitted that he did not use a condom, but added that ‘he had showered afterwards to cut the risk of contracting the infection’ (Peta Reference Peta2008). While many of Zuma’s supporters found his response funny, Zapiro decided to challenge the levity implied in such hilarity by subsequently putting a showerhead on Zuma’s head in every subsequent cartoon in which he featured. Such was the scale of support that Zuma received from his supporters that not only was the home of the woman who accused him of rape burned down, with further threats to ‘burn the bitch’ – which forced her and her mother to seek asylum in the Netherlands (Thamm Reference Thamm2016) – but Zuma was subsequently elected as the leader of the ANC and, following that, as president of South Africa.Footnote 28

In reflecting on this combination of levity and gravity, of lightness and seriousness – as in the Zuma/Zapiro case examined here – which is mirrored in what the sociologist Ebenezer Obadare describes as a ‘state of travesty’ (Reference Obadare2010), Mbembe asks if ‘it [is] enough to say that the postcolonial subject, as a homo ludens, is simply making fun of the commandement, making it an object of derision, as would seem to be the case if we were to apply Bakhtin’s categories’ (Reference Mbembe1992: 7). He states that while such ‘outbursts of ribaldry and derision are actually taking the official world seriously, at face value or at least at the value officialdom itself gives it’, what matters is to realize that ‘the purest expression of commandement is conveyed by a total lack of restraint,Footnote 29 by a great delight too in getting really dirty. Debauchery and buffoonery readily go hand in hand’ (ibid.).

However, contrary to Mbembe’s conclusion that within the ‘postcolonial mode of domination’ obscene laughter constitutes evidence of ‘a practice of conviviality and a stylistic of connivance’ (Reference Mbembe1992: 22), Zapiro’s cartoons point to obscene laughter against – not with – regimes of domination (Werbner Reference Werbner2020: 288).Footnote 30

His Sex-cellency: the African head of state

The proclivity of power for active and ceaseless carnal knowledge, when it eventuates in gruesome outcomes – particularly for the reviled man of power – provides relief for its victims. Anyone who doubts the potential liberating powers of carnality should ask Nigerians. In June 1998, they were liberated from the clutches of a murderous dictatorship by the general’s carnal proclivities – at least, so many believed. When General Sani Abacha, Nigeria’s dictator, suddenly gave up the ghost on 8 June 1998, much of the country celebrated the end of the most vicious regime in the country’s history. The suddenness of his death and the official announcement that Abacha had died as a result of a heart attack led most people to suspect foul play. In no time, rumour circulated in urban areas of Nigeria that the reclusive general had lapsed on the laps of ‘Indian prostitutes’. Before he died, Abacha’s taste for oriental paramours was the stuff of elite gossip in Nigeria. As the Yoruba of south-western Nigeria – who were particular targets of his homicidal rule – would say, Abacha had exited from ‘a door similar to the one from whence he came to the world’. This cultural take, in addition to the rumours that the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), allegedly working in concert with other major intelligence agencies in the West and with Abacha’s adversaries, had decided to take the despot out through his sexual proclivities, seems to capture Mbembe’s elaboration of the intrinsic danger of carnal knowledge Footnote 31 in his response to the critics of On the Postcolony. He argues that, when power grows towards its limits, the phallus as effigy plays ‘a spectral function’. Thus, ‘in seeking to exceed its own boundaries, the body of power (the phallus) exposes its limits, and in exposing them, exposes itself and renders itself vulnerable’ (Mbembe Reference Mbembe2006: 163).

Although the salacious details of Abacha’s death were never officially confirmed, the fact that he and his close friend and fellow soldier General Jeremiah Useni, Minister of the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja – and (in)famously called ‘Jerry Boy’ – had been with some Indian ‘prostitutes’Footnote 32 late into the night before he died was reported by both local and foreign press (Orr Reference Orr1998; Weiner Reference Weiner1998). A Western official in Nigeria told The New York Times, ‘We’ve heard rumours that General Abacha was poisoned while drinking juice, carousing with young women, eating an apple,Footnote 33 even experimenting with Viagra’Footnote 34 (Weiner Reference Weiner1998). Another diplomat told the Irish Times: ‘This was something he did regularly.Footnote 35 He went there [the guest house] to meet two Indian girls in the morning of June 8th and that is where he was poisoned’ (Orr Reference Orr1998).

Whether true or not, what is important is that Nigerians believed that they were saved from his autocracy and the likely breakup of the country by ‘Indian prostitutes’. Rumours circulated about how the CIA, working with some elements within the Nigerian military, either gave the Indians what they used to spike Abacha’s drink or provided the ‘special condoms’ that Abacha used and which slowly killed him.Footnote 36 Whatever the real cause of Abacha’s demise, partly because he was such a detested dictator, Nigerians responded to the rumoured cause of death of a man noted for his ‘highly uncontrolled libido’Footnote 37 with ribaldry. The most common remark was about the ‘Indian apple’ that ‘Abacha bit to death’. A related one was that he ‘sang “Indian waka”Footnote 38 to hell’. Such play on what was assumed to be Abacha’s lechery and the laughter elicited among the direct and indirect victims of his despotism by the rumoured manner of his death are, as Mbembe would have it, a way of ‘reading the signs left, like rubbish, in the wake of [Abacha’s] commandement’ (Reference Mbembe1992: 8).

Certainly, in sexual matters, Abacha was not unique among Nigerian leaders, although he was the only one who is believed to ‘have died on top of a woman’ – something considered to be the worst form of death within Nigeria’s phallocentric cultural world.Footnote 39 For instance, Major Debo Basorun, the former aide to military President Ibrahim Babangida, described how, during a state visit to France, the First Lady, Maryam, physically assaulted the general on suspicion that he had used the excuse of an official meeting that lasted till the early hours of the morning for a ‘tryst’ (Basorun Reference Basorun2013: 222). When Maryam, who was pummelling her husband, eventually opened the door of their hotel suite to allow in a senior military officer who had been summoned by aides to break up the fight, Basorun reports that what they ‘saw was beyond comprehension’: ‘There he was – Nigeria’s military top dog panting and sweating profusely in his roughened service dress with some buttons already ripped off’ (ibid.: 222). Basorun, who was one of the closest aides to Babangida before they fell out (which forced him to flee Nigeria), alleges that Maryam was never able to directly catch her husband with other women, because he ‘was always a step ahead’, but she relied on other cues to provoke a reaction. On this occasion, she ‘allegedly sniffed some strange perfume on her husband’s body which led to accusations of infidelity (ibid.: 221).

What is important about this example is not the truth of the military president’s alleged infidelities, but the effect that the private, marital frictions over infidelities between ‘His Military Highness’ and his powerful wife (who was described by a news magazine as an ‘empress’Footnote 40 ) had on the performance of the former’s public duties. In this instance, because of the fight, Babangida arrived late for an early morning official event in France (Basorun Reference Basorun2013: 222). As Basorun states: ‘Babangida’s occasional squabbles with [his] wife always had an impact on his official productivity. His good and bad days could be as a result of such incident[s] and only close aides with access to the family could hazard a guess as to the cause’ (ibid.). The First Lady’s ‘lack of inhibition’ in discussing her husband’s alleged adultery and their ‘marital hitches’ with others, the ex-aide adds, trumped Babangida’s ‘love for secrecy’ (ibid.).

As the cases of Abacha and Zuma – and, to some extent, Babangida – show, the lecherous leader, whom I have captured here as His Sex-cellency, is not only a common phenomenon in the postcolony; also, the lechery, with the connivance of the dominated, has been normalized. In fact, as Mbembe notes, ‘The unconditional [sometimes conditional] subordination of women to the principle of male pleasure remains one of the pillars upholding the reproduction of the phallocratic system’ (Reference Mbembe1992: 9).

However, some of the (potential) victims of this system employ different means of escape from the unrelenting libidinous threats of the head of state. Charles Piot discusses the Togolese experience, where President Eyadéma uses carnality as a ‘strategy of control’. ‘Eyadéma made a habit of sleeping with the wives of male ministers (and, needless to say, with those few female ministers he appointed),’ writes Piot (Reference Piot2010: 25). This practice, he adds, is ‘clearly rooted in power politics as much as in the sexual appetite of the dictator.’ One minister who had an ‘especially attractive’ wife was said to have ensured that Eyadéma never set his lecherous eyes on her (ibid.).Footnote 41 The late Zairean dictator and kleptocrat, Mobutu Sese Seko, was also infamous for his sexual appetite, including rumours that he ‘fathered illegitimate children with [Bobi] Lawada’s [his second wife’s] twin sister’ (Taylor Reference Taylor2011). He married Bobi, who was his mistress, following the death of his wife, and then ‘made her twin sister [Kosia] his new mistress’. It is reported that he ‘joked [with] diplomats on asking whether they met his wife only to say when they said yes that they met his mistress and twin of his wife’.Footnote 42 In ‘Provisional notes’, such practices of phallicism that ignore ‘the array of interdictions surrounding copulation’ (Mbembe Reference Mbembe2006: 167), as displayed by Eyadéma and Mobutu, are described as ‘violent pursuit of wrongdoing to the point of shamelessness’ and ‘the loss of any limits or sense of proportion’ (Mbembe Reference Mbembe1992: 14, 17). Also, such ‘policies’ constitute reflections of the ‘unlimited rights’ of those in positions of authority ‘over those under them’. Mbembe is succinct in noting that these ‘rights’ ‘exempt acts of copulation from inclusion in the category of what is “shameful”’ (ibid.: 23). Like Eyadéma, a Nigerian head of state is alleged to have slept with most of the women in his first cabinet. It was said that he took exception to one of his female ministers who was a concubine of his deputy, asking her, ‘Why go for number two when number one is available to you?’Footnote 43

‘Inappropriate intimacies’ as family affairs

President Olusegun Obasanjo is one of the most internationally respected leaders in Africa. Apart from being a two-time head of state – and two-term president – of Africa’s most populous country, Nigeria, he also claims to be a ‘born-again’ Christian. In fact, after he finished his term as president, he registered at the National Open University of Nigeria (NOUN) and received a PhD in Christian theology in 2017 (Kayode-Adedeji Reference Kayode-Adedeji2017). Although allegations of his affairs with several women were common,Footnote 44 many people were shocked when, in January 2018, his first son, Gbenga, ‘dropped a bombshell’, as Sahara Reporters described it, about his father’s alleged ‘sexual intimacy with his wife, Moji’.Footnote 45 In an affidavit he submitted to the court in a bitter divorce case, the son of the former president stated that ‘he knows for a fact that the respondent committed adultery [incest?] with and had an intimate, sexual relationship with his own father, General Olusegun Obasanjo, in order to get contracts from the government’ (ibid.). In the affidavit, the estranged husband claimed that Moji was given lucrative oil contracts by her father-in-law in return for sexual favours (Last Reference Last2008).

Although Moji denied the allegations, the marriage was eventually dissolved the following year. While the allegations of incest and incestuous adultery made headlines in the newspapers both in Nigeria and abroad, it was significant that President Obasanjo never responded to them. He carried on with his public life as if nothing was amiss. He didn’t seem to lose any of his social or political standing either in Nigeria or abroad over this. He continued to preach in churches and to make a show of being a ‘born-again’ Christian. Was this because most people didn’t believe the allegations or that they didn’t care? Did Obasanjo consider the allegations damaging? If so, why didn’t he deny them publicly? Could it be because he knew that it would have no effect on his reputation anyway?

When asked about the allegations, the man who was foisted on the ruling party by Obasanjo as the national chair, Dr Ahmadu Ali, told the press that ‘the sex scandal rocking the former first family is entirely’ a ‘family affair’, thus ignoring the ‘various commentators [who] have called on the PDP to expel Obasanjo from the party’.Footnote 46 There are several other urban legends about Obasanjo and women in NigeriaFootnote 47 – one even made it into the diplomatic cables from the American embassy in Nigeria to the State Department in Washington DC, as revealed by WikiLeaks. NEXT newspaper published the story of the 19 October 2007 cable from the US chargé d’affaires, which detailed ‘the different contending groups pulling and pushing for the soul of the ruling People’s Democratic Party’, in which the first female speaker of the House of Representatives, Mrs Patricia Etteh, was mentioned as not only ‘a member of the former president’s network [in the ruling] PDP, but also … Mr Obasanjo’s girlfriend’ (Akinbajo Reference Akinbajo2011). The ‘dubious rise’ of the woman, described by the American diplomat as a ‘former hairdresser [and] romantic interest of Obasanjo’, in becoming the number four citizen of Nigeria was ‘believed … [to be] on the back of Mr Obasanjo’. When NEXT contacted Etteh – who was forced to resign from her position as speaker due to allegations of corruption about four months after she was elected – she reportedly told the newspaper, ‘I don’t bloody care. I can have romantic interest with anybody. I am free to romance anybody’ (ibid.) Perhaps Obasanjo will write about these accusations in another memoir – since he didn’t mention them in his three-volume memoir published after he left office. But, given the way in which everyone – perhaps with the exception of Gbenga, and maybe Moji – moved on, particularly after the allegations about his daughter-in-law, one can suggest that the ‘mutual zombification’ of the dominant and the dominated has so normalized obscenity and grotesquery such that, in the end, even (allegations of) aberrant carnalities or ‘inappropriate intimacies’ (Stoler Reference Stoler2010 [2002]: xv) do not disrupt the people’s estimation of the powerful or interrupt their public lives. Although such scandals may ‘stub the toe’ of the dominant, as Mbembe (Reference Mbembe1992: 10) observes, he ‘glides unperturbed over them’. Thus, in the postcolony, the ‘taste for lecherous living’, ‘the total lack of restraint’ and ‘a great delight … in getting really dirty’, to use Mbembe’s phrases, do not seem to effectively destroy the ‘reputations’ of the dominant.

Yet, such a theory of carnal sovereignty based on popular expectations of male virility, particularly in figures of authority, must recognize the limits of the excess of carnal power. Contrary to Mbembe’s conclusion about the relationship between power’s excess and humour in the postcolony, complicity on the part of the dominated does not imply absolute loss of agency and critique. Thus, while they are implicated in licensing power’s sexual transgressions, the dominated retain a critical measure of distance through their capacity to laugh at (and not with) expressions of the carnality of power. As Zapiro’s Zuma cartoons and Eyadéma’s case show, regular people retain the power of humour as a critique of the carnality of power. Therefore, complicity is never complete. Among the dominated, there is always a space to deride carnal power.

Conclusion

What I have tried to do in this article is extend Mbembe’s insight on a particular characteristic of commandement in the postcolony: that is, its ‘tendency to excess and a lack of proportion’ (Reference Mbembe1992: 3), especially as this manifests in commandement’s ‘marked taste for lecherous living’ (ibid.: 6). I have provided further examples of why this insight is useful for reflecting on the confluence of the political and the erotic. In examining how power ‘animate[s] and enflesh[es]’Footnote 48 – to use Povinelli’s (Reference Povinelli2006: 3) instructive phrase – I have tried to make a supplementary contribution to Mbembe’s study of how, in the postcolony, power regards carnality as a way of distributing, if not sharing, life with the gendered other Footnote 49 (cf. Povinelli Reference Povinelli2006: 3).

In closing, I will make three points. First, reflecting on commandement’s preoccupation with the sexual is not a judgement on the private lives of the specific people who are dominant in postcolonial contexts. This perspective does not necessarily pronounce them as morally wretched, although they may be. As Mbembe states, the ‘notion of obscenity has no moral connotation here’ (Reference Mbembe1992: 14). Thus, when obscenity is ‘regarded as more than a moral category’, we are able to employ it in the analysis of ‘the modalities of power in the postcolony’. This is important because one of the most productive ways of studying ‘the forces of tyranny in black Africa’ is ‘within the confines of … intimacy’ (ibid.: 29).

Second, perhaps as a reflection of the period in Africanist scholarship in which he published his essay, Mbembe concentrated exclusively on heterosexual relationships in describing obscenity and grotesquery (see also Pype Reference Pype2022). However, I do not think that Mbembe, by doing so, was engaging in heteronormative analysis. As two of the most important coups d’état in Nigeria have shown, the dominant’s homosexual relations (real or alleged) can also be the basis of particular forms of reactions to commandement. Although homosexuality has always been criminalized in Nigeria (first as ‘sodomy’ in the colonial and early postcolonial eras, and, since 2014, under the Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act, which banned gay marriage and same-sex ‘amorous relationships’), many believe that it is only the powerful who are able to ‘enjoy’ homosexual or bisexual lives without let or hindrance – though mostly in secret.Footnote 50 Homosexuality was first forced into the political space in Nigeria in 1966 when, in the broadcast announcing the overthrow of Nigeria’s first post-independence government, the coup plotters stated that homosexuality, among other offences, would be ‘punishable by death sentence’ (see Adegbija Reference Adegbija1995). It has since been rumoured that this was directed at the highest levels of political power in Nigeria at this point. There were suggestions that it was impossible to belong to some of the most exclusive political and military cliques in certain parts of Nigeria without being bisexual. The rumours gained greater credence twenty-four years later – that is, in 1990. In announcing what turned out to be an abortive coup, Major Gideon Orkar accused General Ibrahim Babangida of running not only a ‘dictatorial, drug-baronish … deceitful’ government, but also ‘a homosexually-centred’ administration (ibid.). Therefore, it is useful to go beyond heterosexual relations in reflecting on commandement, in relation to what Mbembe describes as the ‘obsession with orifices, odours and genital organs’, given that, at both elite and mass levels, people ‘wield concepts of femininity, masculinity, and homophobia (heteronormativity) as tools’ (Sperling Reference Sperling2015: 2) of politics, particularly because of the ‘accessibility and resonance’ of these as aspects of ‘popular cultural production’ that ‘makes the assertion of masculinity a vehicle for power’ (ibid.: 3, 4, emphasis in the original) possible.

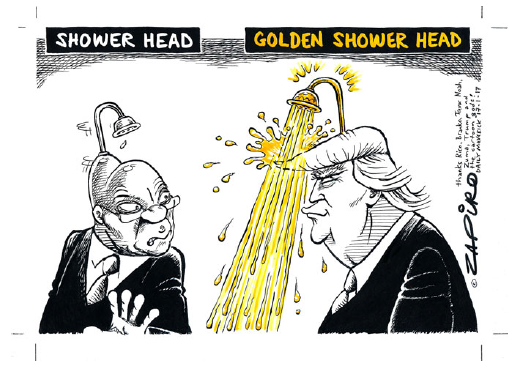

Third, as Mbembe insisted, examining such manifestations of ‘the tropicalities of His Excellency’ (Reference Mbembe1992: 6) as I have done here does not mean that this is an exclusive African (postcolonial) phenomenon. Thus, these examples of the carnality of power do not constitute, as he says, an ‘aspect of a rather crude, primitive culture. Rather, I would argue that … [they constitute] classical ingredients in the production of power, and that there is nothing specifically African about it’ (ibid.: 6). As the infamous examples of (allegations of) lecherous relationships involving presidents Bill Clinton and Donald TrumpFootnote 51 and Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi (of the notorious ‘Bunga Bunga’ case)Footnote 52 show, there is nothing tropical about the carnality of power. In fact, the correlation – or mutuality, in some cases – between carnality and power is what is fundamentally at stake here, as Zapiro also illustrates in a ‘(golden) showerhead’ cartoon pointing to the ‘affinity’ between Zuma and Trump (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Birds of a shower: Zapiro’s take on Trump’s alleged ‘golden shower’ in relation to Zuma’s ‘shower’ claims. © 2008–2017 Zapiro. Republished with permission.

While the postcolonial manifestations of such a correlation may follow a particular trajectory, the fact that Trump grabbed and continues to grab power and influence (over a substantial percentage of Americans), even in the context of his self-advertised proclivity for grabbing female genitalia, reminds us of the constant lecherous potential of power everywhere. For such men of power, to use Lyotard’s words, ‘There is no libidinal dignity, nor libidinal fraternity, there are [only] libidinal contacts’ (1993 [1974]: 113). Here, like Mbembe in ‘Provisional notes’, I have demonstrated only the specific manifestations of the carnality of power in the postcolony, especially given the low level of institutionalization in such states that emerged from colonization.

Acknowledgements

I thank Katrien Pype, Ebenezer Obadare, Rogers Orock and one of the journal’s anonymous reviewers for their critical comments that helped to clarify my arguments. My gratitude to Jonathan Shapiro (Zapiro) for permission to use his cartoons. I am also grateful to the Oxford School of Global and Area Studies (OSGA), University of Oxford, for research support.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Wale Adebanwi is the Presidential Penn Compact Professor of Africana Studies, University of Pennsylvania. He is also an Honorary Research Associate at the African Studies Centre, University of Oxford.