Introduction

Towards the end of 2016, many in Brazzaville – Congolese nationals and foreigners alike – started to feel that it was much more difficult than before to transfer francs CFA out of the CEMAC zone.Footnote 1 This feeling came from various experiences: higher transaction fees; unfavourable exchange rates or lower daily quotas at money-transfer agencies such as Western Union and MoneyGram; or, for corporations, stricter requirements for supporting documents, prolonged review processes, or rejections of transfers by commercial banks or the BEAC.Footnote 2 Yang Shan, the general manager of the Congo branch of a mid-sized conglomerate in China, complained to me about his experiences of paying one of his foreign suppliers:

You know how difficult it is to transfer money now. For this transaction I ran to multiple banks. Most of them told me they didn’t have any forex [foreign exchange] available. Now I finally made it through the bank but the money was returned because of a typo [in a document]! And the banks here don’t want to help me out.

Frustration with international money transfers has been common in the CEMAC countries since then. This situation opened up a unique window into the dynamics of money markets in contemporary Central Africa. Based on in-depth interviews with forex users and bank managers, observations in several transfer agencies, and close reading of relevant marketing and regulatory texts, this article examines the paperwork-based practices and regulations of international transfers of the franc CFA in Brazzaville from early 2016 to 2021. This was a period when the forex reserve of the BEAC shrank rapidly and regulatory practices relating to forex transfer kept changing, and when a new law regarding forex regulations, widely believed to be used to address shortages, came into force in 2019.Footnote 3 I argue that the paperwork for forex-related transactions has a major impact on the channels – and especially the speed – of money flows in the CEMAC zone. Rather than explicitly cutting off the flow outright or resorting to adjustments in the exchange rate, the BEAC’s policies of paperwork regulate forex flows by, among other mechanisms, changing the speed of this flow and, consequently, its cost. Thus, I conceptualize the dynamics of paperwork as ‘bureaucratic valves’: the techniques of paperwork through which regulators’ requirements and reviews, forex buyers’ preparations and manoeuvres, intermediates’ strategies and guidance influence the speed and the cost of forex transactions. Bureaucratic valves are a contested arena in which regulators have the dominant power to shape the flow of forex, but other participants – banks, money-transfer agencies and forex users – also try to turn the valves to their own advantage with varied levels of success.

This article contributes to the current anthropological analyses of documents by showing in detail how the actors involved, with their different and changing interests, actually use them. It also extends the analysis of paperwork from a national and administrative framework (in such issues as tax, land registration and immigration) to an international and commercial setting – namely, forex transactions. Theorizing paperwork as valves influenced by different forces reveals how paperwork can be used to flexibly fine-tune transactional processes in complex and changing configurations of powers and interests. A deeper empirical engagement with the dynamics of paperwork in such settings, I suggest, is essential for both illuminating forex dynamics as a key part of central banking and theorizing paperwork in other practices of governance and commercial exchanges.

Money and paperwork: anthropological perspectives

Anthropological studies of money have long examined interactions among different forms of money, especially in Africa (Bohannan Reference Bohannan1959; Guyer Reference Guyer and Guyer1995; Hart and Ortiz Reference Hart and Ortiz2014). These studies tend to focus on the entities being exchanged in transactions, be they money, things or financial products (Ekejiuba Reference Ekejiuba and Guyer1995; Hart Reference Hart1986; Rogers Reference Rogers2014). Things such as paperwork that are important for such transactions to take place but not exchanged are often simply dismissed as obstacles (Bähre Reference Bähre2012) without much in-depth investigation (Hashim and Meagher Reference Hashim and Meagher1999). Other studies on finance in Africa emphasize the power of social connections and cultural ideas and the prevalent uncertainty in shaping financial activities, showing their fluidity and incalculability in Africa (Kusimba Reference Kusimba2021; Maurer Reference Maurer2007). Formalities, which are seen as obstructing rather than facilitating the regulation of the complexity of African social life, could be pared down to improve efficiency in governmental programmes (Ferguson Reference Ferguson2007). Yet Jane Guyer shows that documents have significant bearings on economic activities in Africa and urges anthropology ‘to focus ethnographic attention’ on them, especially through ‘the analysis of economic documents “at work”’ (Guyer Reference Guyer2004: 158, 162). More recently, Maxim Bolt underlines that ‘the formal economy is far less reflected upon in anthropology’ and warns that ‘there are dangers in assuming that we already know enough about formalized arrangements’ (Reference Bolt2021: 977).

Although less focused on economic activities, recent studies of paperwork have demonstrated its importance in many other aspects of social life, especially in state and organizational governance (Harper Reference Harper1998; Guyer Reference Guyer2004; Hansen and Vaa Reference Hansen, Vaa, Hansen and Vaa2004; Roitman Reference Roitman2005; Riles Reference Riles and Riles2006; Hull Reference Hull2012a; Reference Hull2012b; Bolt Reference Bolt and Adebanwi2017; Reference Bolt2021; Mizes and Cirolia Reference Mizes and Cirolia2018; Muñoz Reference Muñoz2018; Cooper-Knock and Owen Reference Cooper-Knock and Owen2018). This strand of inquiry has turned the analytical focus of paperwork onto its material forms, especially by seeing documents not only as messengers of what are written on them. Guyer, for example, indicates that, in Africa, documents are experienced as unreliable, incoherent and subject to negotiation, despite their appearance of fixity (Reference Guyer2004: 158). Hull goes further in his ethnography of paper documents in Islamabad, arguing that documents, as signs, ‘are things’ (Reference Hull2012b: 13) and that they should be approached according to the ways in which they are produced, used and interpreted. Bolt shows that, despite all the inadequacies of governmental documents, urban Black South Africans use them selectively in disputes to ‘borrow the state’s authority’ to justify their inheritance of urban housing, thus giving rise to a ‘fluctuating formality’ (Reference Bolt2021: 988).

Yet these findings, emerging in occasions of governance, are still difficult to square with the roles of paperwork in transactional scenarios. One such difficulty, which this article addresses, is that the regulation of forex and other transactions requires valves that can be fine-tuned rather than all-or-nothing switches. Many current studies conceptualize paperwork as ‘laissez-passer’ (Hull Reference Hull2012a; Lombard Reference Lombard2013; Bolt Reference Bolt and Adebanwi2017; Muñoz Reference Muñoz2018; Piot Reference Piot2019). In such a conceptualization, paperwork either allows certain things to happen or does not. The effectiveness and specificities of paperwork are contingent on other mechanisms, such as informal conversations, kickbacks and improvisational enactments of social relationships – mechanisms that are, in short, outside ‘the formal’. Reducing the effects of paperwork back to the informal, I suggest, does not further anthropological research into the formal sector. Paperwork itself can sometimes fine-tune transactions. This is all the more important where the daily number of actors and transactions is massive and where participants’ interests are ever changing and ambiguous due to volatile market forces (Blundo and Le Meur Reference Blundo, Le Meur, Blundo and Le Meur2008: 15). In such situations, it is impossible to negotiate every transaction through informal connections before nailing them down in paperwork. Forex transactions in Central Africa have these characteristics. Here, paperwork itself becomes an arena of market negotiations among a multiplicity of participants with different and changing interests. Hence, this study of forex attempts to reconceptualize the role of paperwork: rather than a ‘laissez-passer’, paperwork might also be seen as a valve that adjusts the speed and cost of the transaction it regulates.

To analyse the role of paperwork in this multiple-actor, variegated financial landscape (Siu Reference Siu2019), I draw on Paul Kockelman’s concept of ‘channel’ (Reference Kockelman2010: 419). It helps to conceptualize the flow of forex by stressing that channels are always subject to various interferences. One of the key qualities of the channels subject to such intervention is the speed with which things pass through them (or the bandwidth of the channel). Similarly, Bill Maurer indicates that the purpose of due diligence in setting up offshore companies in Caribbean tax havens is not that all information collected is indisputably true but that it ‘slows things down’ (Reference Maurer2005: 486), implying the importance of controlling the speed of a procedure.

Combining the two perspectives of channels and speed, I suggest that paperwork can be usefully conceptualized as a bureaucratic valve that can adjust the speeds and costs of flows of different resources. In the case of forex transfer, valves can be tightened (slower/more costly movement of money) or loosened (faster/cheaper movement), not only by the most powerful actors in the field, but also by other actors in their own ways. Although in general the more powerful actors in forex transactions, such as the BEAC and large banks, tighten valves when forex is scarce and loosen them when abundant, the complex and changing interactions between different parties sometimes make their behaviour less predictable, as the ethnography below will show. This is precisely why paperwork is better theorized as a valve rather than a pure obstacle. Adopting this conceptualization, this article also brings African experiences into the current anthropological discussion on changes in central banking practices, which so far focuses more on discursive tools and includes hardly any areas other than Western economies (Holmes Reference Holmes2013; Riles Reference Riles2018).

The ins and outs of forex in Congo: oil price, the franc CFA, and the mandatory deposit of forex

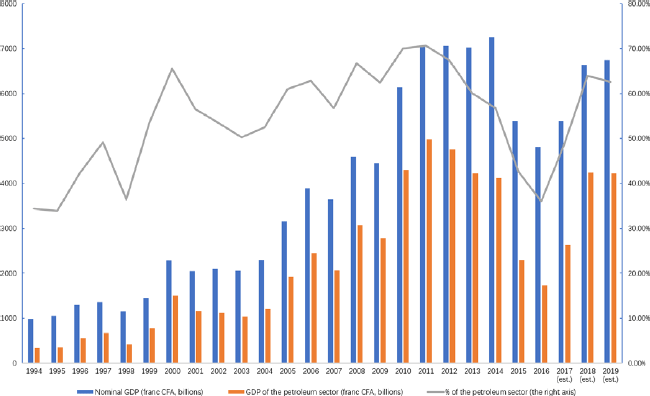

The general situation of forex in Congo and the CEMAC is largely determined by two factors: the price of oil and the institution of the franc CFA. For most years since 1994, the oil sector has constituted more than half of the annual GDP of Congo (see Figure 1). It is also the sector that receives most investment and generates the most exports and, as a consequence, forex.Footnote 4

Figure 1. The percentage of the petroleum sector in the Congolese economy measured by GDP.

Many economic indices of Congo reflect the havoc wreaked by the slump in oil prices since 2015. Figure 1 shows that a significant shrinkage of Congo GDP took place between 2015 and 2017. During the same period, exports also decreased from roughly 70 per cent of GDP to less than 60 per cent. Figure 2 shows the change of foreign reserves of the BEAC and of the Congo in recent years.Footnote 5

Figure 2. The amount of foreign reserves in the CEMAC and Congo.

In 2016, the total assets of the BEAC shrank by more than 30 per cent, and its foreign reserve diminished by more than half. Congo’s foreign reserve at the BEAC contracted by more than two-thirds. Deprived of forex and burdened by rapidly accumulating external debts, the BEAC had few choices but to control the outflow of foreign exchange.

The franc CFA is a currency with two subtypes used in West and Central Africa, most of whose countries are francophone.Footnote 6 In Central Africa, the franc CFA (Coopération Financière en Afrique centrale) is used in the CEMAC. Several key features of the franc CFA system were fixed at the very beginning of its establishment in 1945 and remain unchanged. First, except for a one-time devaluation of 50 per cent in 1994, the franc CFA is pegged to a European currency, first with the French franc and then with the euro when the latter replaced the franc. Second, the French Treasury maintains this pegging and guarantees an unlimited convertibility between the franc CFA and the euro. But this guarantee requires in turn that the forex reserves of the member states are centralized at two levels: at regional level, the member states deposit their reserve at the central banks issuing francs; and at the systemic level, the central banks deposit half of their reserve at the French Treasury. If the deposits at the French Treasury or the two central banks fall below a threshold, there would be additional limits on the credit line from these central banks and other punitive policies. Third, transfer within the sub-regions is unlimited.Footnote 7

The apparent pegged exchange rate between the franc CFA and the euro does not mean that the actual exchange between them or between the franc CFA and other hard currencies is always frictionless and follows the same procedure. As Sara Berry points out, ‘stable prices need not reflect stable … conditions or processes of exchange’ (Reference Berry2007: 60). In choppy times of forex shortage, the process can be highly complex and unpredictable. Like Jane Guyer’s ethnography of the allocation of limited oil at a station in Nigeria (Reference Guyer2004: 107–10), the forex transfer between 2016 and 2020 in Central Africa is this allocation process writ large. But here, paperwork plays a much more prominent role in determining who gets how much forex, how soon, and through whom.

Paperwork and its manoeuvre in forex transfer before the new regulation

Quite unlike other banking services, international money transfer is highly accessible in Brazzaville. Even those without a bank account can transfer money easily in a money-transfer agency. Because of the strong demand, many microfinance institutions in Congo choose to highlight their money-transfer services in their advertisements (Figure 3). Even during the recent economic downturn caused by the pandemic, new money-transfer agencies were still being opened in Brazzaville (Figure 4).

Figure 3. A microfinance agency in Brazzaville, marking its categorization (‘1ère CAT. AGREMENT’) on the board as required by the financial regulator in the CEMAC. This sign highlights its money-transfer service (‘TRANSFERT D'ARGENT’).

Figure 4. A new office for multiple transfer agencies was under construction in May 2021 in a high-end supermarket in downtown Brazzaville.

Before the acute forex shortage in the CEMAC fully developed in 2017, the international transfer of money had been an essential source of income for banks in Congo. MABank, a commercial bank established in the 2010s in Congo, gained almost half of its annual revenue in its first two years from transferring money rather than from the interest on loans. Given the complexity and importance of its money-transfer service, this bank annually organizes open information sessions for its clients to clarify the procedure and the required documents for international transfer. In one of the sessions in 2017, Ma Keduo, the director of the bank’s department of financial markets, summarized six different channels for transferring money in Congo in a table, arranged implicitly from the most informal to the most formal (translated and reproduced in Table 1). As the table shows, even before the new regulation of 2019, paperwork was already functioning to direct forex flows into different channels. For each channel, he commented on its advantages and weaknesses. According to him, the first three channels, which are popular among individual merchants, have fewer requirements for paperwork but higher costs. The bank-based channels, by contrast, are placed at the bottom. He stressed their low cost but was candid about the trouble involved in preparing documents for these channels.

Table 1. Available channels for transferring money

Generally speaking, the major trade-off among these different channels is between cost and paperwork. During my fieldwork, I found all six channels in active use by different groups of users. The paperwork-gated channels are less expensive and less risky than those without much requirement for paperwork. But they can be afforded only by middle-sized and large corporations, because it takes extra effort to prepare the documents. This is best reflected by the experiences of individual traders of petty goods in Congo. They generally do not use banks to make international transfers, neither for imports nor for personal use. There are several reasons for this. First, the BEAC requires that the buyer of forex must be the same individual or institution as the importer. Yet, in practice, the traders often do not import by themselves. Instead, they use service agencies so that they can import things together to share the cost of shipping. Hence, the name of the importer and the name of the buyer of forex do not always match. Second, the providers of these traders are also operating without full paperwork for import/export. Face-to-face trade and familiarity between providers and buyers enable contracts to be dispensed with, but such contracts are often essential to justify making international transfers at the banks in the CEMAC. Consequently, these merchants, despite their central role in providing goods for daily use in Congo, often settle for the more expensive channel with fewer requirements for formalities.Footnote 8

For those corporations well equipped with the paperwork necessary for forex transactions, commercial banks have an interest in facilitating such transactions, since they are a significant source of revenue and profit. To do this, the banks have adjusted the flow of paperwork. As Table 1 shows in its last line, MABank had a priority service that could save time in paperwork processing. In this service, the bank would use its own sources of forexFootnote 9 to meet the needs of its clients before submitting relevant documents to the BEAC for authorization and forex credits. In an ordinary service, by contrast, the bank would submit the documents first to the BEAC and then wait for the authorized credit of forex. Using this priority service, clients would not have to wait for review and authorization by the BEAC before making the transfer. In practice, this service has enabled a number of clients to dispense with the waiting time at a slightly higher cost, and MABank was able to gain significantly from these transactions before the new regulation came into force.

It should not be assumed that there had been no changes in the regulation of forex transfers before the promulgation of the new framework in 2019. In fact, the BEAC also had an interest in altering the flow of paperwork, and actually did so, but on different grounds. In 2015, the BEAC tweaked the paperwork flow, which expedited forex transactions of small amounts. As explained by another MABank bank manager, the BEAC required the commercial banks, starting from October 2015, to execute transfers of amounts equal to or less than 100 million francs CFA (around US$183,000) using their own forex resources before sending the relevant documents to the BEAC for the forex credit. The reasons for this change, according to the manager, could have been the insufficient staffing at the BEAC for handling all the application materials, especially those relating to small amounts. He also implied that, by doing this, the forex held by the commercial banks themselves would be more fully mobilized for such transactions, so that the BEAC could keep its own forex for a longer time. Whatever the motivations were, this adjustment in the flow of paperwork facilitated the international transfer of small amounts by saving the time spent waiting for the BEAC’s authorization.

These international transfer settings before the new regulation in 2019 clearly reflect how paperwork plays a significant role in differentiating channels of forex flows. First, access to certain documents – such as purchase contracts and customs clearance forms – allows some forex users (usually formal business corporations) to use less expensive channels (see Table 1) – namely banks – whereas individual merchants and informal companies without access to such paperwork had to rely on more costly approaches. Second, commercial banks and the BEAC achieved their goals of changing the speed of forex flows by rearranging the paperwork flow. It should be stressed that, although the two actors came to similar paperwork-based solutions, they did so out of different motivations: generating more profits from forex transfer services for the commercial banks; and lessening the burden of regulatory work for the BEAC. Later, during the severe shortage, especially after the new regulation came into force, paperwork would remain at the centre of different manoeuvres and the varying interests driving them.

Tightening the valve: forex shortage and the new regulation in 2019 – and their effects

One way to tighten the bureaucratic valve and slow down the flow it controls is to require more paperwork. Such requirements create a significant amount of work to collect, organize, shape and review documents correctly. When this work increases, more time is needed to prepare the paperwork before the flow of forex can be set in motion. This was exactly the effect of the 2019 forex regulation framework.

The new framework, signed at the ministerial meeting of the CEMAC at the end of 2018 and coming into force on 1 March 2019, overhauled the previous regulatory system created in 2000 (hereafter, the 2019 version and 2000 version, respectively).Footnote 10 A comparison of the key texts of the two systems reveals that the fundamental change in the 2019 version is the centralization of power and forex at the BEAC. Before, the ministries of finance of the member states had much more leeway in allowing forex transactions, and large stocks of forex were held by commercial banks and large export companies in the CEMAC, notably those in the oil and mineral sectors. In a general approach favouring the free flow of money, the 2000 version stipulates: ‘The payments relative to the current international transactions … are free, whereas the movement of capital is, to a very large extent, free.’ The only specified cap is 10 million francs CFA (about US$16,900) for transactions relating to foreign movable properties (Article 5). By contrast, Article 6 of the 2019 version, mainly concerning the same issue, has a much more moderate tone in terms of the freedom of money flows: ‘All the transfers, payments, and settlements of current transactions to a foreign destination, subject to the justification of the origin of the funds and the presentation of the documents required by the foreign exchange regulation, can be executed freely’ (emphasis added). It sets a much lower, all-encompassing and accumulative cap for transactions exempted from the requirement for multiple documents: 1 million francs CFA (about US$1,700) per person per month for all kinds of transfers. Therefore, the number of transactions to be accompanied by such paperwork grew exponentially.

This new regulation made forex transfer difficult at all levels, from individuals to large corporations. Individual traders are among the most severely impacted because they need forex regularly to import goods. Mr Yu and his family are among them. They have a shop facing the main avenue in Poto-Poto, one of the busiest market areas in Brazzaville where foreign traders are concentrated (Whitehouse Reference Whitehouse2012). Yu sells goods for daily use: battery-powered lamps, shoes, plastic flowers, schoolbags, and so on. He came to Congo from China for petty commerce in 2010. All of his goods are imported from China. He is in charge of handling everything related to forex for the shop, and he was fairly open when talking about his experiences in making money transfers. He used one word to characterize transferring money – nan, meaning difficult in Chinese – and he repeated it multiple times during my interview with him in his shop. He was quick to get into the details, saying that this difficulty began only two years before (roughly 2017). According to him, starting from 2017, the transfer limit was changed to 1 million francs CFA per passport per month at Western Union. This limit was too low for the imports his shop needed; on average, he could generate a turnover of this amount in only a couple of days. He was also unwilling to use the more informal channels of money transfer, such as those operated by networks of money dealers, which charged transaction fees higher than his profit margin. In fact, he was so sensitive to the fluctuations in the foreign exchange rates and transaction fees that he remembered in exact numbers the various costs of transferring 1 million francs CFA through Western Union in recent years, and he could rattle them off without skipping a beat. In one of our conversations in his shop, he explained:

Usually, if you transfer 1 million francs CFA through Western Union, you will get €1,524 at the recipient side. If you choose informal money agencies, you will only get €1,480. And it would take three to five days to arrive, so I would be worrying about that … Nine years ago, the transaction fee was about 72,000 francs CFA [for 1 million francs CFA]. Then, for a long time, it was kept at 65,000 francs. In February this year, the transaction fee was 41,300 francs, but you only got €1,471 at the recipient side. Soon it reverted to €1,524, but the transaction fee was 100,150 francs. The latest rate you get [is] €1,524 at a 56,150 francs fee.

His extraordinary sensitivity to marginal gains (Guyer Reference Guyer2004) from actual exchange rates and transaction fees reflects the significance of money transfers to his transcontinental business. As if recalling something painful, he told me that there had been a period when 1 million francs CFA were worth only 9,700 yuan, a rate at which he had no profit margin at all. He seriously wanted to quit the business then. But at the time of the interview in 2019, his main difficulty became the daily limit on the amount of money one could transfer out of the CEMAC area. In addition to the limit on individuals, money-transfer shops also have a daily quota. Once the daily quota is used up, which usually happens early in the morning, for the whole day no more money can be transferred out of the CEMAC from that shop. As Yu recalled, there was a time when people in urgent need of forex had to start to wait as early as 2 a.m. Hearing our discussion on the experience of transferring money, his wife weighed in by stressing the importance of oiling the hands of the clerks of those agencies and keeping a good personal relationship with them so that they could reserve some quota.

Yu’s experiences are shared by many other users of forex in Brazzaville. Mukié, a middle-aged Congolese woman, explained to me in the small yard of her home in the Bacongo area of Brazzaville how difficult it was to transfer money out of Congo. She frequently sends money to some of her family members in France. To do this, she said, ‘Now you have to go there [money-transfer agencies] early, otherwise the daily quota [of the agency] will be used up. Sometimes I even have to wait for days.’ Her friend sitting next to her, a younger Congolese woman who often travels between China and Congo for trade, confirmed the difficulty by stressing that she could not get enough foreign cash in Congo for her payments in China. Rather, she would use prepaid Visa cards, a tool introduced by several commercial banks into Congo and intensively marketed around the same time of the forex shortage to facilitate overseas payments. Raj, an Indian entrepreneur in the travel business in Congo, also complained to me of his friend’s extra loss caused by a delayed transfer of forex for payment overseas.

For banks and corporations, it was hardly any easier to make forex transfers. Client managers of MABank fielded calls or visits almost every day from their corporate clients asking about the procedures for making transfers or the progress of their applications. Given the significantly increased requirements for paperwork, almost no clients were able to get everything right at the first submission; the back and forth of application materials between the banks and their corporate clients were inevitable and took much time and energy on both sides.

Even with the help of banks, the outcome of the reviewing process at the BEAC was highly uncertain. As the bank managers I knew well often say, ‘There are so many documents [required for the transaction]. It is always easy to find something wrong if they [the BEAC reviewers] want to.’ Sometimes the reviewing process was so slow and uncertain that, when the authorization was finally issued, the client’s money that had originally been prepared for transfer had already been used for other purposes. Moreover, the specific requirements for certain paperwork keep changing. In an interview in 2020, one of the managers at MABank showed me an importation declaration form for the BEAC with a blank cell marked as ‘Douane’ (customs). She said: ‘It worked before [leaving this cell unstamped by customs]. But now we are asked to get it stamped.’ What was more irritating for her was that, in the portfolio of required documents, there was already another import declaration from customs. ‘Now it just means you have to get customs’ consent for the same thing twice’ (Figure 5).

Figure 5. A redacted internal MABank form used to check whether a forex application has all the necessary documents. Notice that, as the document requirements changed, the original design became outdated and was left unused; handwritten notes were used instead (see the last box in the form with the title ‘Remarque(s)’).

The case of several forex transfer applications made in early 2020 by MM, a mid-sized oil company in Congo, reflects the multiple ways in which paperwork can shape the forex flow and often breed ad hoc documents not contained in the legal framework. In January and February, three applications made by MM to pay an overseas supplier were rejected in a row, because the BEAC claimed that MM had lacked the required documents for two previous forex transfers. The managers of both MM and MABank were astonished by this reason, as the two transfers had been approved and completed by the BEAC. Moreover, the rejection letter from the BEAC, signed by its national director for Congo, claimed that it would block all future applications from MM until this issue were solved. In their preparation for resubmitting the ‘missing’ documents, the managers anticipated one issue: the date of the invoice. The original invoice was dated 2018, when the import took place, but they thought it might be deemed invalid for the review in 2020 because of the two-year time gap. So, the manager of MM asked the supplier for a new invoice with a date in 2019, the time of the actual payment for the import, and prepared a letter explaining the process. A senior executive of the bank also signed a supporting letter. Together with these materials relating to previous successful applications, they submitted new applications for forex.

Yet they got another rejection letter in March; this cited the problem that, in the submitted documents, the date of customs clearance was before the date of the invoice, which meant that the invoice might be for some other transactions. No advice on how to address this issue was given in the letter. Later, the managers of MM and the bank had to visit the national branch of the BEAC in Congo. According to the managers, the BEAC staff member who received them knew about their situation, even without consulting the relevant records. In the brief meeting, the member of staff told them to submit yet another letter, provided by the supplier, to explain the delay in the payment. After they acted accordingly, the application was approved.

Such increased and changing requirements for paperwork reflect the fact that the paperwork required for forex transactions is not only for passing on information. It is equally about the energy and effort invested in putting that information in the right form, the right order, and the right amount. As the example of the customs stamps and the case of MM show, even if there are other documents already passing on certain information (in the former case, customs authorization), once they are not in the right number or the right order in the eyes of the BEAC, they will not work. Since the acute shortage of forex fully set in around 2017, and especially since the new regulation of 2019 came into force, most of the back and forth between bank managers and their clients has been devoted to getting the right types and quantity of documents in place, making the information in those documents consistent, and meeting the changing requirements of the BEAC. This energy and effort put into paperwork are precisely what Maurer has called ‘due diligence’ (Reference Maurer2005), in the sense that the amount of labour spent in preparing it is as important as the veracity of its contents.

Responses to the new regulation: further tightening and loosening the valve

Participants in forex transactions, other than the BEAC, also turn the valve of paperwork using their own strategies. Their interests change in different circumstances, so they turn the valve in different directions at different times.

Individual forex users cope with restrictions by going to the agencies early, but, more importantly, they have their own paperwork strategies: borrowing IDs. Currently, the monthly quota of forex for individuals is 1 million francs CFA, which is far too low for traders such as Yu for their businesses. So, before the day of the transfer, Yu would borrow many passports and identity cards from local people. On that day, he would get up very early, bring all the documents and IDs he had collected to the agency with which he was familiar and wait for it to open. Sometimes, he would have to go to multiple agencies, as some small agencies had such a limited quota for each day that it could be used up in the early morning. Another Chinese entrepreneur told me that there were some people who specialized in using multiple IDs to transfer money for others and who made a profit from this service.

It seemed that this manoeuvre was widely used and forex transfer agencies were complicit. As part of my fieldwork, one day I went to the downtown branch of a major transfer agency and asked if I could transfer 2 million francs CFA to China. The clerk confirmed that such a transfer was possible, and showed me the quote on the computer screen: €1,524. I expressed my doubt to her by saying that I had heard elsewhere that there was a 1 million per day limit. She shrugged, saying, ‘You can bring two IDs.’ Those more compliant agencies would post conspicuous notices stating: ‘The holders of IDs must be present when making forex transfers.’

Some Congolese entrepreneurs seized this opportunity to develop their businesses in forex transfer, often highlighting their document-free services. They strategized their connections outside the CEMAC to secure their own sources of forex. Kimya, a middle-aged entrepreneur who runs a money-transfer agency in a busy street of Brazzaville, told me that her success was attributable to the onset of the difficulty in getting forex. In 2016 and 2017, when the problems were most severe, she was able to secure forex in cash from Kinshasa. She frequented both sides of the Congo River to meet the demands of forex in Brazzaville, which usually came from government officials and athletes who needed forex in cash while travelling abroad. Thus, her business was animated by the history of ‘reciprocity of influence’ between Brazzaville and Kinshasa (Gondola Reference Gondola1997; M’Bemba-Ndoumba Reference M’Bemba-Ndoumba2021). Imana, a young man who had studied in China, used his network of Congolese students and Chinese friends in China to open up a digital service that specialized in money transfers between Congo and China. This fulfilled a strong demand in Congo as there were many Congolese students and traders in China. Neither entrepreneur’s services were cheaper than banks or money-transfer agencies, but their businesses thrived by providing access to forex for targeted clients without the trouble of getting documents.

The reactions of banks were ambivalent, despite their interest in facilitating forex transfers. In fact, after the new regulation came into force, some banks further tightened the valves of paperwork to such an extent that the BEAC had to intervene. In the period examined in this article, the BEAC often used circular letters addressed to its offices in the member states and to the commercial banks in its jurisdiction to specify detailed requirements for forex transactions, especially around the time of the 2019 regulation coming into force, as details were not pinned down in law. A close reading of those letters available to the author reveals two kinds of reaction from the banks. The first was to refuse, without any explanation, to execute their clients’ requests to make transfers, as revealed by two letters issued by the governor of the BEAC in the week following the implementation of the new regulation. According to the first letter, which was addressed to the national directors of the BEAC, these banks explained their refusal by ‘spreading the erroneous information that there might be a scarcity of foreign exchange in the sub-region and that the Central Bank … might be the source of the refusal to execute the orders of transfers made by clients at their counter’.Footnote 11 The real reason for the refusal, the governor wrote, was that the banks were deciding whether to accept their clients’ applications for forex transfer using the banks’ own positions (holdings) of forex. He stressed that the banks should be executing their clients’ requests whenever their foreign positions allowed; if not, the documents were to be forwarded to the BEAC to finance the operation (ibid.). In the letter concerning the same issue but addressed to the directors of the banks in the CEMAC, the governor stressed that there was no shortage of foreign exchange and that the BEAC had a ‘comfortable margin’ to meet the demand of the CEMAC economy.Footnote 12 As these two letters show, it is obvious that certain banks chose to avoid dealing with some forex transactions during the transition period of the new regulation. By refusing to serve their clients at their bank counters on the grounds of the scarcity of forex in the region, the banks would avoid the cost of spending too much time on preparing the documents as well as the risk of being rejected, and they shifted responsibility for failing to make the transfers to the general situation and the BEAC.

This explanation becomes more plausible when we consider the second kind of reaction, also reflected in the letters, which was to ask clients for more documents than required by the BEAC. In a letter issued on 9 December 2019, addressed to the directors of commercial banks in the CEMAC, the governor of the BEAC pointed out that ‘excessive documents, sometimes irrelevant to the object of the payment, were demanded from your clients for the settlement of their operations to foreign destinations’.Footnote 13 He criticized such a practice as contributing to ‘on the one hand, the prolongation of the delay in executing operations … on the other hand, the degradation of the indicators for evaluating the climate of business in our zone’. He did not suggest any possible reasons for the banks to ask for more documents than necessary in the letter. One of the possible reasons was that the banks were unsure about the changing regulation framework, so they asked for more than was necessary just in case the BEAC made demands for unexpected documents. Or this may have been a soft version of the direct rejection discussed above. Whatever the motivation was, it is noteworthy that this reaction was realized by manoeuvring paperwork. Whether to deter transactions or to avoid risks, commercial banks, similar to their regulators, also turned the bureaucratic valve to achieve their own ends. In this case, their reactions amplified the tightening effort from the BEAC, making transfers even slower.

These circular letters reflected an interesting attitude on the part of the BEAC towards the tightening of the valve of forex flow. Despite the dramatic increase in obstacles, the BEAC still tried to convey its steadfast support for free forex transactions. This standpoint was best shown in a public conference organized by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the BEAC on the economic situation of Congo in May 2019. The speeches of the panellists focused on investment, economic growth, and measures for stabilizing the credit market. The issue of forex transfer appeared only marginally, as a small part of the banking sector to be ‘stabilized’ in the crisis. It was also mentioned only in passing by a bank manager in the Q&A session in his question about the coordination between the BEAC and the governments of its member states. At the very last moment of the conference, however, the speaker from the BEAC proactively offered to explain the situation of forex transfer in the CEMAC. He claimed to use a situation in which there were ‘economic actors, members of parliament, and ambassadors in the hall’ to confirm that ‘there is no forex control’. He was keen to make sure that this sentence was heard, repeating it several times during his unsolicited intervention. He acknowledged that there were difficulties in making forex transfers, but explained the reason as follows:

It’s just a more rigorous implementation of a regulation which has not been applied for twenty years. Why? Because we used to be practically on a level of forex of 1 trillion francs CFA. This enabled the banks to transfer the forex as much as they wanted.

Then he stressed the obligatory repatriation and resale of forex to the BEAC – namely, the requirement that companies receiving forex from their overseas transactions need to transfer them back to Congo and sell them to the BEAC in exchange for the franc CFA, which ‘allows the guarantee of monetary stability’ but can cause some difficulty in forex transfer.

In these remarks, the central banker was using a communicative tool – a proactive explanation of central banking policies – to build up the public’s confidence and solicit their support (Holmes Reference Holmes2013), and to shape the expectation of important forex users, for whom forex control is hardly desirable. Yet for a small and weak economy like the CEMAC, communication between central bank officials and economic actors might be less effective in combating a crisis than it is between Western central banks and economies. The BEAC needed something more concrete than pure discourse to retain forex. It is here that the bureaucratic valve came in – namely, the ‘more rigorous implementation of a regulation’, in the words of the BEAC official quoted above. The valves allowed the BEAC to slow down forex outflow in practice without openly admitting the shrinkage of forex holdings, a claim that might further discourage economic activities and deteriorate the forex situation. Doing so enables communicative and substantive stability for central banking at the same time.

It should be stressed that the BEAC’s aim is not to retain as much forex as possible. It also adjusts the bureaucratic valve in favour of forex flows once stability is achieved to some extent. Indeed, on 6 November 2019, the BEAC loosened the valve by issuing a letter informing the banks that it would allow them, each week, to combine transfer applications of up to 50 million francs CFA into one single package and the BEAC would execute these applications without further review process, a channel that has been functioning well since then.Footnote 14

The subtle relations between the BEAC, the commercial banks, money-transfer agencies and individual forex transferers discussed above show that paperwork in forex transactions in Congo constitutes multiple contested valves that different players try to turn to their own advantage, with their own interests changing according to different circumstances. There is no predetermined antagonism in forex transactions; the interests of participants, and hence their dealings with paperwork, change with circumstances. Banks might help their clients for the pursuit of profits as well as reject them right away to avoid unnecessary risks or burdens; the BEAC might facilitate forex transactions to better mobilize the forex resources it has or block them to achieve target forex positions. These actors are constantly negotiating with each other for their own interests, which might be diametrically different as circumstances change.Footnote 15 Therefore, the conceptualization of this dynamic as a contested valve, influenced by multiple agencies, rather than as a unidirectional laissez-passer is more useful in shedding light on its fluid processes of negotiation with changing interests.

Conclusion

In this article, I suggest that forex flows in the CEMAC area are largely shaped by what I call bureaucratic valves – namely, the paperwork manoeuvres required for forex transactions. These valves influence the speed and the costs of different channels of these flows, be they money-transfer agencies, banks or others, by requiring more or less paperwork and rearranging its review process. In the time of urgent need for retaining more forex in the CEMAC, the financial regulator required more paperwork for forex transactions. When such pressure is relieved, these requirements are in turn eased. Meanwhile, different actors involved in these transactions, such as forex buyers, money-transfer agencies and banks, play with and around these paperwork requirements to pursue their own diverse interests. Although limited compared with the regulator, they nevertheless are able to shape the flows of forex through the same bureaucratic valve.

One might argue that, boiled down to the basics, it was the lack of forex and the centralization of all available forex at the BEAC rather than paperwork that made forex transfer so difficult in the CEMAC. This is not totally wrong, but if we overlook the role of paperwork, we cannot understand what these forex users and regulators busied themselves with during the shortage. They did not just leave the forex locked up in the BEAC with folded arms. Rather, they were busier than before to get transfers done. Only by highlighting the central role of paperwork in this system of forex regulation can we understand this intensified ‘busyness’ during the shortage, and, more importantly, the uses and effects of paperwork in formal economies.

The concept of the ‘bureaucratic valve’ refers to a dynamic interaction mediated by paperwork among actors involved in forex transactions in Central Africa, rather than the modus operandi of the BEAC itself. In this sense, this concept is akin to James Ferguson’s ‘anti-politics machine’, which theorizes the effects of interactions among multiple actors in foreign aid programmes in Lesotho in the 1970s and 1980s (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1994). For him, such effects constitute a ‘subjectless’ power that is not intended by any single actor but turns out to be an unexpected outcome of the complex dynamics of different stakeholders (ibid.: 18–19). In a similar vein, the ‘bureaucratic valve’ tries less to expose the ‘hidden intentions’ of the BEAC (which are hugely ambiguous and fluid anyway, as shown above) than to characterize the actual practices of transferring forex in Central Africa.

This study also demonstrates the diverse and changing interests in the use of paperwork across a wide range of actors. As Muñoz aptly argues in his study on the governing of cattle traders and truck drivers in northern Cameroon, the study of government needs to go beyond ‘dyadic interactions between rulers and ruled’ (Reference Muñoz2018: 162). The speed and cost that such valves can influence are key arenas of ‘the daily negotiation of bureaucratic powers’ (Blundo and Le Meur Reference Blundo, Le Meur, Blundo and Le Meur2008: 20), key mediators of ‘multiple rationales’ in African states and supra-state actors such as the BEAC (Bierschenk and Olivier de Sardan Reference Bierschenk, Olivier de Sardan, Bierschenk and Olivier de Sardan2014: 19), and key products of the ‘political energy, physical effort and scarce resources’ of users and regulators (Cooper-Knock and Owen Reference Cooper-Knock and Owen2018: 276). Hence, although the ethnography here is conducted in Congo, the concept of bureaucratic valves is helpful for understanding paperwork in transactional and governmental practices in Africa and probably elsewhere, especially when they involve multiple parties.

Finally, this study is an attempt to ethnographically study macro-economic practices, such as central banking (Appel Reference Appel2017; Hibou and Samuel Reference Hibou and Samuel2011; Riles Reference Riles2018). It shows that paperwork can be an effective tool for adjusting forex flows, especially in smaller and weaker economies such as the CEMAC. It thus complements current anthropological studies of central banking, which focus more on central bankers’ discursive and informational connections with the public and concentrate on Western economies. Moreover, existing ethnographic research on central banking is mostly concerned with the setting of interest rates and the collection of economic information; the task of managing forex, crucial for the central banking of smaller economies without stable sources of forex, is relatively less studied from a central banking perspective.Footnote 16 Hence, those practices related to forex and the regulation of them seem an important aspect and a promising path of ethnographic approaches to central banking and macro-economic activities, because of their direct connection with many actors, on both local and global levels.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Wenner-Gren Foundation and Yale University. I thank my interlocutors who made this research possible. The anonymous reviewers provided me with many inspirational suggestions and editorial help. I also benefited from the discussions with and the comments by Helen Siu, Douglas Rogers, Louisa Lombard, Paul Kockelman, Janet Roitman, Hannah Appel, Vanessa Waters Opalo, Nishita Trisal, and many others. I appreciate their support in the making of this paper.

Rundong Ning is a PhD candidate in the Department of Anthropology at Yale University. His dissertation project is about entrepreneurship and changing modes of work in Congo-Brazzaville. His research interests include entrepreneurship, finance, volunteerism and STS.