Dε pœ ge baa ye? Who, then, arranges (dresses, prepares) the ge?

Ge nin ge baa. It's the ge who arranges the ge.

The above text, which I heard sung in call-and-response style at several Dan ge (mask spirit)Footnote 1 performances in Côte d'Ivoire in the 1990s, is one element of getan, or the music/dance aspect of the manifestation of ge. This text goes to the heart of the ambiguous notion of agency practised by mask spirit performers among both Dan and Mau peoples, at home in Côte d'Ivoire and in immigrant contexts in the US. ‘Who, then, dresses and/or prepares the ge?’ the call asks. ‘It's the ge that dresses and/or prepares the ge,’ comes the ironic reply.

At its most fundamental level, this song plays on the ontological ambiguity surrounding such mask spirit performances. Many people who identify as Dan and Mau believe a masked dancer in performance is a manifestation of a spirit being, not a human in costume. In most Dan and Mau community contexts in Côte d'Ivoire, the question ‘Who, then, arranges the ge?’ is clearly rhetorical. People generally know that the belief system – a loose-knit but widely shared interpretive frame through which people interrelate various practices involving extra-human agency – holds that no one arranges the ge. The answer ‘It's the ge who arranges the ge’ upholds this belief. When mask spirit performers professionalize and their performances move to the stage, however, the commodification process challenges this belief and its related practice of not naming a person behind the mask. The challenges associated with staging and commodification are present to a degree in professional mask performance practice in Côte d'Ivoire. But such challenges become even more commonplace in the context of the US.

In this article,Footnote 2 I briefly describe the belief system at the centre of Mau and Dan mask spirit performances and some implications of these beliefs in practice, and I suggest an ontological framework for interpreting the ambiguous agency embodied in Dan and Mau mask spirit performances. I ground my discussion of this ontological framework by juxtaposing ethnographic material about non-commercial, community-based mask spirit belief and practice with details of the career of an international ‘star’ mask spirit performer, Vado Diomande. Philosopher Barry Smith describes ontology, or the study of being, as a stream of philosophy exploring ‘the science of what is’ (Reference Smith and Floridi2003: 155). In other words, ontology involves classification of ‘the kinds and structures of objects, properties, events, processes and relations in every area of reality’ (ibid.). By addressing the issue of the agency of mask spirit performers as a question of ontology, I am joining conversations in recent anthropological literature about the challenges of conducting ethnography of spiritual (and other intangible) phenomena. For example, in the introduction of The Social Life of Spirits – a recent collection of essays exploring theoretical and methodological issues related to anthropological research of intangible phenomena – anthropologists Ruy Blanes and Diana Espírito Santo ask, ‘How do we work (around, with, as) an “anthropology of intangibles”?’ (Reference Blanes, Santo, Blanes and Santo2013: 4). In answering their own question, Blanes and Santo argue that anthropologists of ‘intangible’ phenomena should ‘begin from the premises of [intangible entities’] influence, extension, or multiplication in the world’ rather than from ‘substantive ontological pre-definitions’ (ibid.: 7). Focusing on the intangible entity itself as a substantive object is problematic because ‘there is no easy answer as to what an “entity” is, or at least one that bases itself upon a straightforward or preconceived idea of agency’ (ibid.: 17). As such, Blanes and Santo recommend focusing the ethnographic lens on the tangible effects of non-human agency, in the form of its observable downstream results.

As I read it, then, Blanes and Santo’s recommendation supports a fluxist theory of ontology – one focused on the existence of being in events and processes (‘occurents’) rather than things or substances (‘continuants’) (Smith Reference Smith and Floridi2003: 155). Building on Blanes and Santo’s questioning of the efficacy of casting the intangible entity as a substantive study object, I propose here that the ambiguous agency at the heart of Dan and Mau mask spirit performance is best understood using a performance framework that locates being in process. My interlocutors’ discourse about and practices of these performances suggest that, rather than looking for ontology in performance, we understand ontology as performance – or perhaps better yet, performance as ontology. Existence, then, is located in process and performance, not independent from them. Such a framework illuminates both the challenges and the strategic advantages that ontological ambiguity presents to mask spirit performers in immigrant settings in the US. This ontological framework, which is consistent with Dan and Mau performance practice and discourse that I have learned through ethnographic research both in Côte d'Ivoire and in the US, also provides a philosophical grounding to theories positing African art as process. Revisiting these theories from an ontological perspective, I endeavour to better understand the ways in which mask spirit performers manoeuvre in the interstices of display and disguise (see also Harding Reference Harding1998), addressing both belief and market demand.

Human being spirit

In my ethnographic research on mask spirit performances both in Côte d'Ivoire and with Ivorian immigrants in the US, I have found that certain ideas and practices are shared among people who identify as Mau or Dan. In this sense, my research supports the argument that ethnic boundaries, so clearly drawn on colonial and postcolonial maps of African states, can be deceiving in their seeming implication of isolable, even bounded, ethnic communities (cf. Kopytoff Reference Kopytoff and Kopytoff1987). In reality, a great deal of exchange has historically occurred and still takes place between and among people who identify variously as Mau and Dan, especially – but far from only – in the frontier zone where large populations of both ethnicities live. Not surprisingly, then, many traditions are shared between the two groups, from textiles to rhythms to mask spirit belief and practice. Such sharing of traditions is to some degree ironic given the extent to which Dan and Mau people themselves will sometimes emphasize the Dan-ness or Mau-ness of certain cultural practices (such as ge itself, which some Dan interlocutors asserted was at the core of what it means to be Dan; see Reed Reference Reed2003). On one point, however, I have found unanimous agreement: that the stilt mask spirit originated in the Dan region and eventually was adopted by people further north in the region commonly considered Mau. The extent to which Dan and Mau individuals with whom I have conducted ethnographic research share belief and practice should therefore not come as a surprise.

Conducting research for my book Dan Ge Performance (Reference Reed2003), I questioned many people, including initiates – ritual specialists, dancers, musicians and healers – and non-initiates to explore mask spirits from multiple perspectives to get at an intersubjective construction of meanings surrounding such performances in people's experience. While I found myriad perspectives and ideas about Ge,Footnote 3 I began to notice that many people's experience involved a loose-knit set of ideas that constituted something like a system of belief and practice. In using the term ‘system’, I do not mean to suggest a single, monolithic structure whose specifics were uniformly shared (cf. Reed Reference Reed2003: 69–72). In discussions, Dan people expressed considerable variety in the details concerning categories of spirits and processes of communication with them. Yet, it was very common for people to profess that such a system existed and to interpret their and others’ practices based on this systematic framework. No one better articulated ideas about this system of belief than one of my Dan teachers, elder Gueu Gbe Alphonse, who had this to say about the process of performance and ontology:

The mask, the wearer … there is the raffia, there is what they put on the head, there are the pants, the bubu (shirt) … that whole ensemble, which is material, and worn by a human who, from the moment that he is dressed like that, and that he is in that disposition, becomes spirit … From the instant that he places himself behind the mask, he becomes different. He is inhabited by a wisdom, he is transported, he transcends, and at the moment, he becomes at the same time the physical mask that you see, and he becomes at the same time, spirit. (Gueu Gbe quoted in Reed Reference Reed2003: 87)

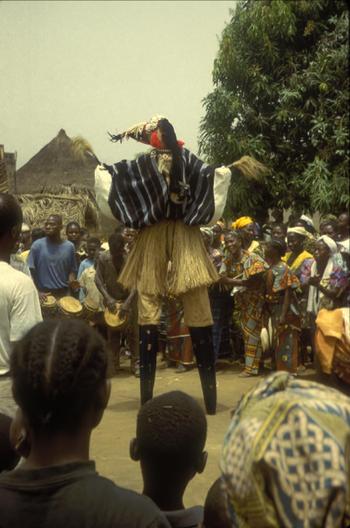

In public discourse, the performing ge is a spirit manifest (Figure 1). There is no human present.Footnote 4 Yet, in Dan and Mau community contexts, everyone aside from very young children know that a person is ‘behind the mask’ of a performing ge, and many people know who the person dancing a particular ge is. This information, however, cannot be spoken in public. People deliberately talk around the issue, finding creative ways to discuss the subject of Ge performance without naming names. An intentional ambiguity surrounds this aspect of Ge performance; it is permissible to know, but not to say, that there is a person beneath the dancing figure. Taking my interlocutors literally, a dancing ge is not a person embodying a spirit, but rather the ge is the spirit itself.Footnote 5 As I heard Dan people sing at several performances in Côte d'Ivoire in the 1990s, ‘Gewon ye ɗœ’ (‘The matter of Ge exists’). Ge performance does not represent; it is. My Dan and Mau teachers interpret mask spirit performance as being, via an ontological interpretive frame.

Figure 1 Stilt mask spirit Gue Man, Biélé, Côte d'Ivoire, 1997.

In my publications based on this research, I have chosen to write about this issue with this same sense of deliberate ambiguity. Although in the past I did not name anyone who ‘accompanied’ or was ‘behind’ any ge, readers might have inferred who they were, which is acceptable. I chose this tack both to adhere to my ethical obligations regarding this matter, and to attempt to represent in my writing the way in which Dan people talked with me about it.Footnote 6 Ethically, I always made clear to interlocutors that my intention was not to unveil secrets. I asked them to tell me if our conversations had accidentally veered into the domain of protected knowledge, and promised them that I would never write about or otherwise share such information, including the identities of mask spirit performers. When Dan people themselves talked about this subject, the intentional ambiguity came into play. Asked where a prominent member of the community might be who always seemed to be missing when a particular mask spirit was performing, people often suggested that he was ‘away on travel’. In interviews with participants following a performance, when everyone in the room was aware of who had been behind the mask, we would not address that person directly, but instead would discuss the dancing mask spirit using the third person.

At issue, then, is the fact that answering the question posed in the opening song with a human being's name – especially in community contexts – is technically sacrilege, and would invite a consequence such as an attack in the spiritual realm (in Dan duyaa, generally translated as ‘sorcery’). As I have written elsewhere (Reed Reference Reed2003), this presents an odd predicament for someone concerned with issues of agency, as I am. In some regions of Africa, masked dancers can be identified by name. In her influential book on Pende masquerade, Z. S. Strother freely identifies masked dancers to draw connections between history and agency (Strother Reference Strother1998). Patrick McNaughton, in his book on Bamana artist Sidi Ballo, bases his entire argument on the importance of this individual – his personality, his artistry – to understanding the bird masquerade (McNaughton Reference McNaughton2008). This is not the case for the Mau or Dan people in community contexts, who are not permitted to name a mask dancer in a public setting. And yet, when mask performances become staged, this custom inevitably is altered. The processes of commodification render protection of a mask spirit dancer's identity not only more difficult to maintain, but also less desirable on the part of the performer(s). In this sense, my interlocutors echo Frances Harding's observation that Tiv kwagh-hir performers ‘sustain a tension between concealing the identity of a human wearer and then – especially in particularly successful and popular performances – seeking ways to reveal their identities before and afterward’ (Reference Strother1998: 57). My recent writing about the lives of Ivorian immigrant performers in the US has had to reflect that change as well (Reed Reference Reed2016). The stories of individual immigrant performers are replete with their individual recognition and naming, and yet the notion of ambiguous agency also persists in the various practices of mask performers who take to the stage.

Becoming known

It was Vado Diomande's ability dancing Gue Pelou – the stilt mask (nya ya in Mau) for which his family was known in the region – that landed him his first job in 1974 at age seventeen as a founding member of the Ballet National de Côte d'Ivoire, launching a career now spanning forty years.Footnote 7 Prior to the competitive process that led to his selection, Vado had for years been recognized by his fellow Toufinga villagers for his superlative skills in dance. That Vado was singled out as a kind of child dance prodigy in his village is not surprising in light of his familial background. Vado's family is a ‘mask family’, meaning that they have a long-standing tradition of being the guardians and performers of sacred mask spirits. In western Côte d'Ivoire among ethnic groups such as the Mau and their neighbours to the south, the Dan, only certain select families ‘own’ masks, and ownership of masks is inherited patrilineally. These families possess not only physical belongings – the sacred houses in which masks and related sacred paraphernalia are kept – but also access to the spirits and the right to manifest them in performance. Historically, only members of these families performed mask spirits and the various traditions associated with them, although in the last few decades of the twentieth century people from outside these families increasingly began joining in (Reed Reference Reed2003: 21). These masks are spirit beings, only some of whom manifest among humans in performance.

While Vado comes from a so-called ‘mask family’, this fact alone did not guarantee his becoming a highly skilled practitioner. Generally in mask families, one man in the family becomes the primary ‘proprietor’ of the mask. Vado's father was one such proprietor, the member of his generation who had what Vado alternately termed ‘the gift’ or ‘the power’. As among Dan people (Reed Reference Reed2003), when a baby is born in a mask family, family members assess whether or not the newborn possesses ‘the power’ (fan in Mau). In fact, it was even before Vado's birth that his father identified him as the next proprietor of the mask. Vado explained: ‘I had lots of big brothers, but the mask doesn't come to everyone. They all danced, but it wasn't the same thing. The power only comes to one person.’ Because this was the first time he had identified this inheritance as a ‘power’, I asked him about it. ‘I don't know where the power comes from,’ he said, ‘but it comes to you … it's a gift – my dad had it, too.’ He went on to tell me that this power affects how one dances and sings. ‘Everyone can [dance and sing] well, but when they see me do it, they say, “That's different!”’

Many people in western Côte d'Ivoire would interpret the ‘difference’ that Toufinga residents observed in Vado's dancing as the presence of spirits (singular: yinan (Dan); ginan (Mau)). Vado acknowledges that ‘the ginan make the dance powerful. When the good ginan come, the dance has a lot of power. Good energy.’ Ginan also accompany and empower another category of spirits – that is, the category central to this discussion: mask spirits (ge (Dan); nya (Mau)) – when they manifest in performance among humans. Intermediaries between people and God, mask spirits appear most commonly as dancing masked figures. Vado confirmed what my Dan teachers had taught me in Côte d'Ivoire in the 1990s: that a performing mask spirit manifests social ideals by being the best at whatever it does. Among Dan people, for example, no human can solve sorcery conflicts as effectively as the genre of ge (zu ge; see Reed Reference Reed2003: 157–70) charged with this task, and no human dancer can dance better than a dance ge (tankœ ge; ibid.: 149–56).Footnote 8 Not surprisingly, then, Vado asserts that Mau masks also embody ideal behaviour by being the best at what they do. He extended this argument to the selection process of the Ballet National de Côte d'Ivoire. ‘It works just like this in the ballet. That is, you have to be the best at whatever it is that you do to be in it … and even in the village before you are selected for the ballet you had to be the best.’ To be known as the best, obviously, necessitates being known.

Archival records obtained from the Centre National des Arts et de la Culture – the government ministry that houses the current manifestation of the national ballet (now called the Compagnie National de Danse de Côte d'Ivoire) – support the idea that in 1974, when the ballet was founded, individual talent was one of the criteria used to select performers. The director of the Ministry of Cultural Affairs, Jules Hié Nea, who was charged by President Félix Houphouët-Boigny with creating the national ballet, and its first director, Mamadou Condé, sought to represent the country on stage with a repertoire of dances that were regarded as ‘the most significant and original of their [respective] regions’.Footnote 9 Côte d'Ivoire is particularly well known for its masks, and people tend to associate particular mask performances with one or more of the country's sixty ethnic groups. When the national ballet was formed, organizers selected certain mask performances that were representative of specific regions of the country. Given the prominence of stilt mask performances in the western, mountainous region of the country, it comes as no surprise that the ballet specifically sought a performer with expertise in that genre. In terms of the performers of such traditions, however, the organizers had specific qualities in mind, which included ‘artistic technique’ as well as certain ‘physical and vocal qualities’.Footnote 10 Obviously, individual talent and thus identity were important considerations for the ballet organizers as they went about choosing performers to join the ballet.

Therefore, with regard to his experience as a nya ya performer, Vado's personhood – his family background, his specific identity within that family, his skill-based reputation in his natal village, and his reputation as a dancer on the national stage – mattered and was recognized in his youth and young adulthood. Notwithstanding the shared belief that the performing mask is a spirit manifest and the custom of not publicly naming mask performers, Vado became known, first locally, then regionally, and finally nationally, as an individual endowed with gifts that made his particular manifestations of Gue Pelou noteworthy.

Immigration and commodification

Being selected for the national ballet was a life-altering moment for the young Vado, ushering in a career as a stage performer, choreographer, and eventually director of his own Kotchegna Dance Company. With his fellow founding members of the national ballet, Vado was sent to the city of Bouaké for an intensive two-year residential training that he likens to a military boot camp, during which time he mastered the skill of transforming community-based music and dance traditions into entertainment for the national stage. Following similar patterns to the ballets of other West African countries, the Ivorian ballet made various changes to community performance customs, which included stitching together ethnically marked dances into choreographed dance dramas; opening circular dance patterns into lines; dramatically increasing the numbers of drummers and dancers performing simultaneously; shortening, standardizing and choreographing dance routines; creating a canonized repertoire; arranging rhythmic and dance changes; and more (Schauert Reference Schauert2015; Flaig Reference Flaig2010; Polak Reference Polak and Post2006; Castaldi Reference Castaldi2006; Reed Reference Reed2016).

Remaining with the ballet for fifteen years allowed Vado to build on that initial training and develop even more skills, and he eventually became not just a lead dancer but also a principal choreographer for the group. All this training and experience provided Vado with a skill set in the staging of Ivorian dance traditions that opened up new opportunities for him to enter a transnational market for African music and dance performance (Figure 2). The notion that training for the national stage can serve to prepare performers for a migrant labour market abroad circulates in many West African states. Castaldi writes that the gruelling process of training for the national ballet of Senegal enabled performers to accumulate ‘precious cultural capital’ (Reference Castaldi2006: 173) that they could later employ as a means to make a living abroad. Schauert writes that, within Ghana's two national ensembles, the Ghana Dance Ensemble and the National Dance Company, the idea that performers viewed tours as potential opportunities to ‘seek for greener pastures’ abroad was well known to the point that rules and strictures were put in place as disincentives (Reference Schauert2015: 146–8).Footnote 11 Experience in staging traditions and touring internationally to present shows for audiences in wealthy, Northern countries, coupled with the generally low wages of national ensembles in West African states, renders many performers both well prepared for and especially interested in finding a means – legal or otherwise – to move abroad, most often to Europe or North America, to test their abilities in new, potentially more lucrative markets.

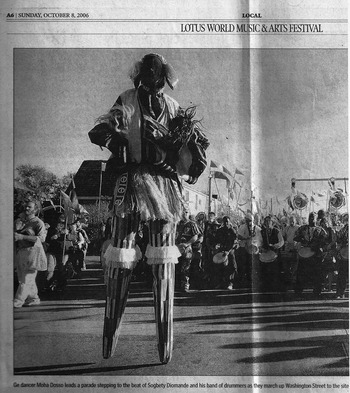

Figure 2 Gue Pelou leading a Lotus Festival parade, Bloomington, Indiana, 2006.

After fifteen years in the national ballet followed by several more years directing and performing with his own, Abidjan-based company, Ensemble Kotchegna, Vado moved to New York in 1994. There, he formed a version of Kotchegna (called the Kotchegna Dance Company) and began making and repairing jembe drums, teaching drumming and dance, and performing as a dancer of many Ivorian traditions, including his speciality, Gue Pelou. Over time, Vado began actively pursuing options for his family members to immigrate to the US, in part to help support his extended family back in Côte d'Ivoire. With the goal of increasing cash flow from the US back home to Toufinga and Abidjan, in 1997 Vado succeeded in making opportunities for his nephews Sogbety Diomande and Moha Dosso to obtain visas and join him in New York. Dosso had assumed the directorship of the original, Abidjan-based Kotchegna in Vado's absence, and Sogbety Diomande, though just a teenager, had become one of the ensemble's featured performers. Vado knew that they were ready for North American stages, and he desperately needed relief from the burden of supporting so many family members:

Vado Diomande Like Sogbety here and Moha … you have to get someone near you. Because Sogbety's father is my big brother, we are of the same mother, same father. I was doing everything [I could to support my brother]! [It's as if they think] I can't do anything good here. ‘Send me money! Send me money!’ [he said]. I stopped everything, I took three months. Finally I got Sogbety here, and [then I thought] ‘Maybe I will rest a little bit’ … I saved money to pay for Sogbety, to get his visa and everything … now [that] Sogbety [is] here … I don't pay anything for [my brother] anymore. Sogbety's supposed to do that. So that's why [these past] ten years have been good for me, now.

Moha [is] helping [on the] other side, too! Moha is my big sister's son … that's why it's good when they are both working, doing well. If I have a problem … they help me, too! When I was sick, they came in … That's good.

Daniel Reed I hadn't understood that before, that when you invite family members here, they can help you support the family back home …

Vado Diomande Yeah! If everything is on you, it's no good. You have to support yourself, you have to support your people, your parents’ people – it's a lot! Because when you are somewhere [far away], everyone wants something from you.

Here, Vado illuminates an important, very practical aspect of the immigration and artistic process. Family members are brought over to join earlier immigrants not just to provide the new arrivals with access to economic betterment and/or the earlier immigrants with more familial support, but also to assist earlier immigrants in the essential task of earning money to support family back home. Anthropologist Paulla Ebron urges scholars to track relationships between aesthetic production and economy more closely in order to better contextualize and interpret staged performances of African music and dance (Reference Ebron2002: 20); in the case of Vado's family, economic concerns drive artistic and religious practice. Sogbety Diomande and Moha Dosso both were born and raised in Vado's home village Toufinga, where they were initiated and trained as nya ya performers. Then both moved to Abidjan – Moha in his early twenties, and Sogbety while still a teenager – where they joined Kotchegna and were trained in essential skills associated with ‘ballet’-style staged stilt mask performance. After spending several years each in New York, both nephews moved to the Midwest – Sogbety to Mansfield, Ohio, and Moha first to Cincinnati, Ohio, and eventually to the small town of Scottsburg in south-east Indiana. From these locations, they are able to increase, one might say, Gue Pelou's audience and market range. Trained in performing the staged version of this religious tradition, Sogbety and Moha have been able to take advantage of economic opportunities that eased their Uncle Vado's burden (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Gue Pelou with Vado Diomande following on drum, St Bernice, Indiana, 2008.

Although there are three sets of physical masquerade paraphernalia in the United States – in New York, Ohio and Indiana – there is but one spirit Gue Pelou.Footnote 12 With Vado at the helm, all three of these individual Mau immigrants dance the ‘same’ mask spirit. Ultimately, according to both Vado and Sogbety, all three Gue Pelou masquerades are extensions of the nya ya ba (‘ba’ being a suffix that literally means ‘great’ or ‘big’) – the great stilt mask back in Toufinga. The belief that a dancing mask is in fact a spirit, not a human, remains. This belief continues to dictate aspects of performance practice and process, particularly in preparations for performances. Vado must make periodic trips from the US back to Toufinga to offer large ‘sacrifices’, which can be a combination of cash and animals to be slaughtered for a huge ritual meal offered to the ancestors on behalf of powerful elders still living who are initiates in the affairs of nya. In his dreams, Vado receives visits from Toufinga spirits, who sometimes demonstrate new dance steps to him, while at other times they inform him of the need for more sacrificial offerings. But no aspect more clearly reveals the ambiguous agency and ontology of Gue Pelou performance than the process of preparing for a performance – the ‘dressing of the mask spirit’ to which the opening song text alludes.

An element that is absolutely required regardless of where a Gue Pelou performance occurs is the creation of a sacred space in a convenient location that can be dedicated exclusively to the preparation of the mask spirit. This practice is rooted in the traditions of rural communities in western Côte d'Ivoire, where specific locations are considered to be sacred spaces through which communication with the spiritual realm occurs. Adjacent to each Dan village is a sacred forest, and those families who inherit the responsibility of maintaining and performing mask spirits have in their compounds one building, a sacred house, dedicated to the storing of sacred objects including those used in a mask spirit performance (such as the mask, clothing, raffia skirt and sacred drums). In village contexts, the preparations for and dressing of a mask spirit for performance will occur only in one of two locations: the sacred house or the sacred forest. Even in Côte d'Ivoire, however, as Dan and Mau people have become urbanized and have moved around the country, and as the distance of travel for masked performance has increased, ‘sacred houses’ are sometimes improvised through the transformation of secular, everyday space into sacred space for the purpose of dressing the mask spirit. I have seen performers in Côte d'Ivoire use a room in a house or an unoccupied building; there are many possibilities, but the key is that the space must be off limits to all non-initiates. The key principle here is that no one other than initiates may witness the dressing and preparing of the mask, or the moment when a human being dons the costume. Dressing the mask is a sacred and secret process, and the transformation from human being into nya or ge is a process in which only initiates are permitted to participate.

In the context of performances in the US, this tradition is maintained by necessity in an adaptable, creative manner. There are no shared dressing rooms – a private space must be guaranteed, or else the mask spirit will not perform. But the location of that space is negotiable. I have witnessed mask spirit performers make use of many types of spaces, including restrooms – in a public school in New York City, in community centres in Atlanta, in the public library and at an outdoor school building in Mansfield, Ohio, in Boys and Girls Clubs, and in Indiana University buildings in Bloomington; in a specially designated room in a convention hotel in Indianapolis; in rooms in the basement of churches in both Bloomington and Scottsburg, Indiana; and in temporary tent shelters in Bloomington and St Bernice, Indiana. Virtually any space will suffice, as long as it is guaranteed to be a private space restricted to initiates of the mask spirit; even other Ivorian immigrant performers are forbidden from entering. Explaining the importance of maintaining this tradition, Sogbety told me: ‘It's the same mask, in the village or here. If it's time to get dressed, nobody can see that. I respect that everywhere I go. It's the same mask; the same spirits are there.’

Ensuring that a space can be reserved for this purpose is a challenging aspect of arranging for Gue Pelou performances in the US, because the mask spirit must have total privacy both before and after a performance, when getting dressed and undressed. At a stage in an outdoor tent at the Lotus Festival of World Music in Bloomington, Indiana, in 2008, all three of the artists performing that evening were scheduled to share the same tent ‘dressing room’. Because I was on the Lotus advisory board and had also helped book my Ivorian friends for the show, Vado approached me to inform me that Gue Pelou could not appear under those conditions. I quickly borrowed a friend's car that was parked nearby, rushed home and grabbed a large tarpaulin and every bungee cord I had, and sped back with my supplies. The stage manager and I then hurriedly constructed a makeshift ‘wall’, with which we divided the tent dressing room in two. Had we not done so, Gue Pelou, often considered the highlight of Ivorian immigrant shows, would not have appeared.

Despite the perpetuation of this custom in immigrant performance contexts, the performer's identity is generally well known. Consider, for example, this article from The Morning Call, Allentown, Pennsylvania's local newspaper, previewing a performance by Vado Diomande's Kotchegna Dance Company on 16 February 2002. The article begins:

Vado Diomande requires twenty minutes of solitude to begin the ritual transformation … For once he puts on the mask, he is no longer Vado Diomande … He becomes Gue Pelou, mediator between the land of the ancestors and the land of the living, a spirit that expresses itself through acrobatic feats performed on stilts. (Craft Reference Craft2002)

The article continues, unveiling the ontological paradox:

Asked if Diomande himself would perform, company manager Lisa Harman answered, simply, ‘Pelou will be there.’ Bridging cultures has caused a considerable challenge for Harman, who must function in an entertainment-driven industry with identity conventions such as ‘Vado Diomande appearing as Gue Pelou.’ (Craft Reference Craft2002)

This is precisely the dilemma, the paradox, these performers face when operating in a capitalist market that commodifies both form and performer and transforms performance into labour. When the press covers Gue Pelou performers, they also want names. In the Bloomington Herald-Times on 8 October 2006 (Figure 4), a photograph of Gue Pelou leading a Lotus Festival parade up the street includes the caption: ‘Ge dancer Moha Dosso leads a parade stepping to the beat of Sogbety Diomande and his band of drummers.’Footnote 13

Figure 4 Bloomington Herald-Times photograph of Gue Pelou leading a Lotus Festival parade on 8 October 2006.

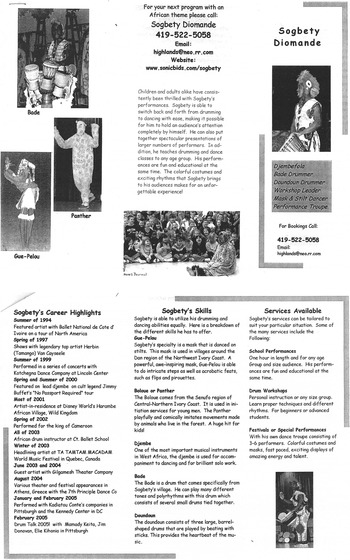

But it is not just journalists who name mask spirit performers in the US. Performers themselves invoke their agency strategically to allow their names to be known when it is advantageous for them to do so. Working within a competitive marketplace, performers must market themselves as individuals so that potential customers can differentiate among performers and know whom to call. Those individual performers must have names, and those names must be associated with the commodity being marketed – the mask spirit. Figure 5 shows two images – the front and back of a trifold brochure to promote Sogbety Diomande. For business purposes, Sogbety identifies himself as a mask and stilt dancer; this is elaborated on the inside of the brochure where Gue Pelou is described in explicit detail. In a capitalist marketplace, one needs to know what ‘services are available’ and whom to contact to purchase them. In another of many possible examples, Figure 6 shows a brochure from the Calico Children's Theatre at the University of Cincinnati Clermont College, where among the series offerings are ‘A Box of Shel Silverstein’, ‘Mystery at Frogwarts’, the film Arctic Express, and ‘masked stilt dancer’ Sogbety Diomande, with accompanying photograph of Gue Pelou.

Figure 5 Trifold brochure promoting Sogbety Diomande.

Figure 6 Promotional flyer for the University of Cincinnati Clermont College Calico Children's Theatre, 2007.

In this sense, Gue Pelou performers in the US are not unlike popular musicians who seek various means, including conventional media, social media and human networks, to market their skills as commodified labour. Inherent in this commodification is a process of transformation of ‘various kinds of value – aesthetic, moral, linguistic, and economic’ (Shipley Reference Shipley2013: 4). Entering into such a process performing a sacred mask, these performers’ cultural and aesthetic practice – language, clothing, music, dance and beliefs – are transformed into labour or product. Also, like pop stars, each individual personality – his name, his image, his identity – must itself become subject to commodification. However, while naming becomes more openly discussed and commonplace in the context of immigrant life in the US, one must remember that individual identification also occurs, if more indirectly, back in Côte d'Ivoire as well. Commodification entered into these performers’ lives not in the US but in Abidjan, and, to some degree, even in the small village of Toufinga.

Ask Sogbety, Vado or Moha directly whom the children will see at the theatre, and they will tell you, ‘Pelou will be there.’ What, then, do we as scholars do with this ambiguous agency? Responding to an essentializing, colonialist representational tradition of making claims for ‘The Yoruba’ or ‘The Dogon’, many scholars now reflexively highlight individual subject positions in ethnographic representations and celebrate African artists as individual agents.Footnote 14 Agonizing over this dilemma, I wrote an email to my Indiana University colleague, art historian Patrick McNaughton, in which I questioned my method of choosing not to name mask spirit performers in my publications and presentations. I wrote: ‘Obscuring agency is the antithesis of my mission as an anti-essentialist Africanist!’ McNaughton wisely replied, ‘YES BUT … obscuring agency is surely a spicy and delightful form of … agency.’ How right he was. To respect the tradition of agency ambivalence of mask spirit performers is precisely to recognize the agency of those same performers to define what they do in their own terms.

Performance as ontology

Considered from this perspective, what ‘is’ the phenomenon of a stilt mask spirit? An agency-centred approach, as ethically and politically important as it may be, that focuses on a substantive being – which sees a dancing mask spirit as a thing, a continuant, a substance – might be missing the point, or at least the point that my teachers have been trying for more than two decades to get across to me. Rather, if in mask spirit performance, what is is an event or process – an occurent or occurrence – then the substantive question regarding being is moot. In a Gue Pelou performance, one is experiencing, rather, a process of spiritual beingness that offers considerable challenges, but also great benefits, to participating performers. Conceptualizing West African mask spirit performance as an occurent can transcend the apparent ‘conceptual disjunction between the performer and the masked figure’ (Harding Reference Harding1998: 57) so commonly described in the literature on these traditions.

The notion of being as process points me back to pioneering African art history scholarship published more than forty years ago, such as Herbert Cole's notion of art as a verb (Reference Cole1969), and Robert Farris Thompson's call to study African art ‘in motion’, as enacted (Reference Thompson1974). These and other interventions in African art history echoed the broader paradigm shift towards process (and specifically, performance) in ethnographic scholarship in fields such as linguistic anthropology, folklore and ethnomusicology in the 1970s (for example, Bauman Reference Bauman1978; Stone Reference Stone2010 [1981]). The call for scholars to de-centre the products of human creative endeavour and focus instead on the social processes that lead to and surround those products was in part an effort to better understand human beings’ engagement with art, which led scholars naturally to concerns of agency. Perhaps the lesson of the ambiguous agency of Gue Pelou performances is that the mask spirit as ‘thing’, or individual being, should not be our focus; rather, it is the process itself – being unfolding in time – that matters.

By choosing to understand mask spirit performance not as the instantiation of being in performance but rather as being as performance, or performance as being, I evoke a specific manifestation of the shift towards process that was made decades ago in my own discipline of ethnomusicology, and that came in the substitution of one two-letter preposition for another in Alan Merriam's definition of the field. Merriam, who had earlier defined ethnomusicology as the study of music in culture (Merriam Reference Merriam1960), in 1977 revised his definition to the study of music as culture (Merriam Reference Merriam1977). This new definition moved the field beyond a functionalist model that presumed culture as some pre-existing system or thing that is somehow reflected in music performance, and towards the understanding that culture is made, or generated, in performance.

Again, however, here I propose not just an understanding of culture as process but ontology as process, a model in which being is its performance. Stuart Hall follows a similar line of thinking in his landmark studies of the performance of diasporic identity, in which he argues that identity is always a process, and ‘always constituted within, not outside, representation’ (Reference Hall, Braziel and Mannur2003: 234). Indeed, Hall advocated that identity is ‘not something that already exists’, but rather is ‘a matter of becoming as well as being’ (ibid.: 236). So, perhaps just as art is a verb, music is a process and identity is its performance, being itself can be understood as an occurrence in time. Blanes and Santo quote William James on this point, who asserts that ‘truth happens to an idea. It becomes true, is made true by events. Its verity is in fact an event, a process; the process namely of its verifying itself, its veri-fication. Its validity is the process of its valid-ation’ (James Reference James2000: 88 quoted in Blanes and Santo Reference Blanes, Santo, Blanes and Santo2013: 7, emphasis in the original).

‘It's the ge that arranges the ge’

So, answering the call ‘Who, then, arranges the ge?’ with the response ‘It's the ge who arranges the ge’ is a proposal of a kind of deliberately ambiguous agency and ontology that is known only in its performance. It is a proposal that scholars should not look for ontology in performance, but rather ontology as performance – or better yet, performance as ontology. In fact, such a position is arguably implicit in the getan lyrics themselves, which suggest that the substantive ‘who’ and the occurrent ‘dressing/preparing’ are conceptually one and the same. The commodification process that occurs when mask spirit performance becomes labour alters but does not eliminate the ambiguity around the agency and identity of the performer. As is always the case when cultural forms migrate – to new performance contexts, to new settings – some aspects of the form are abandoned, some come along for the ride, but all aspects are subjected by performers to a process of examining how the form will best work in the new context. As Vado's nephew and fellow Gue Pelou performer Sogbety Diomande told me: ‘When you're in a new context … you try things that work in that context.’ When Ivorian immigrants perform Gue Pelou in the US, belief and its related ontological ambiguity remain inseparable from the practice.

This ambiguity, however, presents both logistical and practical challenges. Vado Diomande was required to make what might be termed an initial capital investment in the form of a huge sacrifice to the ancestors and the nya ya ba to obtain permission to dance Gue Pelou outside the village. He has to regularly renew that permission by sending sacrifices from the US, and ideally by returning to his village of Toufinga annually to offer substantial sacrifices that one might interpret as annual dues. The traditions surrounding the dressing of the mask spirit create logistical complications that can prevent Gue Pelou from performing, potentially limiting performance opportunities. Ultimately, however, this ontological ambiguity serves performers well, in that it enables them simultaneously to claim that Gue Pelou is a spirit and, when strategically necessary and/or advantageous for them to do so, to draw attention to their human identities. Upholding the beliefs surrounding stilt mask performance offers performers multiple advantages. Most fundamentally, these beliefs animate performers’ abilities to transcend normal human levels of excellence and overcome human limitations in their performances, because, according to their own interpretations, it is the spirit being's agency that is acting, as opposed to mere human agency. Moreover, the periodic sacrificial offerings required to continue dancing Gue Pelou abroad constitute an enactment of belief that, according to performers, maintains necessary good relations with powerful villagers and protects performers from harm that would befall them should they attempt to dance Gue Pelou without such permission. Finally, the belief that Gue Pelou is a spirit is a major draw for North American audiences with an appetite for representations of African exoticism. Meanwhile, ambiguity also leaves space for performers to draw attention to their personal identities when necessary. In contexts such as national ballet auditions, promotional materials and media reporting, allowing human identities to be known enables performers to earn profit as labourers in the transnational marketplace of African dance performance. To be hired, promoted and gain a reputation in the crowded marketplace of the representation of Africa on stage, one must be known. Focusing the ethnographic lens on the processes of mask spirit performance utilizing an interpretive framework that understands ontology as performance illuminates the ambiguous agency at the heart of this practice, as well as the challenges and benefits this ambiguity accords performers.

Acknowledgements

For their support of this project, I acknowledge and thank the following units and programmes at Indiana University: the Office of the Vice President for Research for a New Frontiers in the Arts and Humanities Grant (2008) and a Collaborative Research and Creative Activity Fellowship (2012), the Office of the Vice Provost for Research for a Summer Faculty Fellowship (2014), and the College of Arts and Sciences for a College Arts and Humanities Institute Fellowship (2009). I also wish to thank Paul Schauert, Hsin-wen Hsu and Heather McFarland for their invaluable work as research assistants over the course of this project.