Violence by and towards young people has become a major public health issue. Increased lethality, more random violence and fewer safe places largely account for the high levels of fear experienced by both children and adults. In the field of child protection and domestic violence, where traditionally the child is referred as the victim not the perpetrator, child psychiatrists are well versed, practised and skilled in the assessment of children and families. However, young people are increasingly being referred to child and adolescent mental health teams for assessment because of violent acts that they have carried out. This is reflected in heavy case-loads of children with conduct disorder who have multi-morbidity and complex need. In England and Wales, health (including mental health), social care and education services are mandated to assist youth offending teams.

This all begs the question of what specific training and skills child psychiatrists are given or acquire to carry out this difficult task. This paper raises salient issues and presents possible frameworks within which this work might be undertaken.

Definitions

Violence denotes the ‘forceful infliction of physical injury’ (Reference BlackburnBlackburn, 1993). Aggression involves harmful, threatening or antagonistic behaviour (Reference BerkowitzBerkowitz, 1993). Longitudinal studies are invaluable in mapping out the range of factors and processes that contribute to the development of aggressive behaviour and in showing how they are causally related (Reference Farrington and BoswellFarrington, 2000). Loeber & Hay (1994) described four groups of young people: those who desist from aggression, those whose aggression is stable and continues at the same level, those who escalate in the severity of their aggression and make the transition to violence, and those who show a stable pattern of aggression. However, in attempting to work with any individual who has committed a violent act, the question to be answered is ‘why this individual has behaved in this unique fashion on this occasion’ (Reference Lipsey, Wilson, Loeber and FarringtonLipsey & Wilson, 1998). Violent behaviour often involves the loss of a sense of personal identity and personal value. A young person may engage in actions without concern for future consequences or past commitments.

Learning from the adult literature

Predicting future risk of violent behaviour has a long and difficult history (Reference Dolan and DoyleDolan & Doyle, 2000). There has been a gradual and helpful shift from ‘dangerousness’, as a subjective concept, to ‘risk’, which is a combination of factors, each of which is not necessarily dangerous in itself, that fluctuate over time and that may be modified and managed. Risk assessment and management of violence are key components of clinical practice.

Clinicians have traditionally assessed risk on an individual basis, using case formulation ‘unaided clinical judgement’. Adult research has focused on the accuracy of risk prediction variables in large heterogeneous populations using relatively static actuarial predictions. The debate about clinical v. actuarial risk prediction has led to the development of violence prediction instruments that combine the importance of static actuarial variables and clinical/risk management items that clinicians take into account in risk assessment of individuals.

The MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study (VRAS; Reference Monahan and AppelbaumMonahan & Appelbaum, 2000) highlights the significance of clinical factors in the prediction of violent outcomes in non-forensic psychiatric patients discharged from hospital. Cue domains in the VRAS are grouped under: dispositional factors; historical factors; contextual factors; and clinical factors.

Structured clinical judgements are a composite of empirical knowledge and professional clinical expertise. Webster et al (1997) have developed the Historical/Clinical Risk Management 20-item (HCR–20) scale, where H1–10 relate to history, C1–5 to clinical factors and R1–5 to risk, to assess risk of violence in clinical contexts. This and similar instruments emphasise the importance of the following in risk assessment:

-

• assessments conducted using well-defined published schema

-

• good agreement between assessors, which depends on their training, knowledge and expertise

-

• prediction for a defined type of violent behaviour over a set period

-

• that violent acts are detectable and recorded

-

• that all relevant information is available and substantiated

-

• that actuarial estimates are adjusted only if there is sufficient justification.

Risk assessment in young people

General framework

The literature on specific needs and risk assessment in adolescents who are violent, have mental health problems and/or offend is developing. The issue of assessment is closely linked to the issues of both prevention and treatment.

Reviewing both prospective and retrospective research suggests that victimisation and loss at an early age have consequences for future violent acts, in particular the association of physical abuse and violence. Stiffman et al (1996), in their US longitudinal study, found that a combination of personal variables (gender, substance misuse) and environmental variables (history of child abuse, stressful and traumatic events, rates of unemployment) predicted almost a third of the variance in adolescent violent behaviour.

Sheldrick (1999) suggests a traditional adult forensic approach to risk assessment in young offenders who are violent, breaking down the current incident/offence and historical data (Box 1). It is essential that assessment of empathy for the victim be carried out in the context of the emotional and developmental status of the young person and with an understanding of the protective mechanisms of amnesia and clinical denial following a violent offence/incident.

Box 1 Sheldrick's (1999) model of risk assessment in violent young offenders

Consider the following, looking for situations, triggers, frequency, severity and trends over time

Index offence

Seriousness

Nature and quality

Victim characteristics

Intention and motive

Role in offence

Behaviour

Attitude to offence

Victim empathy

Compassion for others

Past offences

Juvenile record

Number of previous arrests

Convictions for violence

Cautions

Self-reported offending

Past behavioural problems

Violence

Self-harm

Fire-setting

Cruelty to animals

Cruelty to children

Risk escalates when there is failed multi-agency risk assessment and management, which includes failure to respond to reported episodes of violence, poor record-keeping and communication, and taking a cross-sectional rather than long-term view of the young person and his or her behaviour.

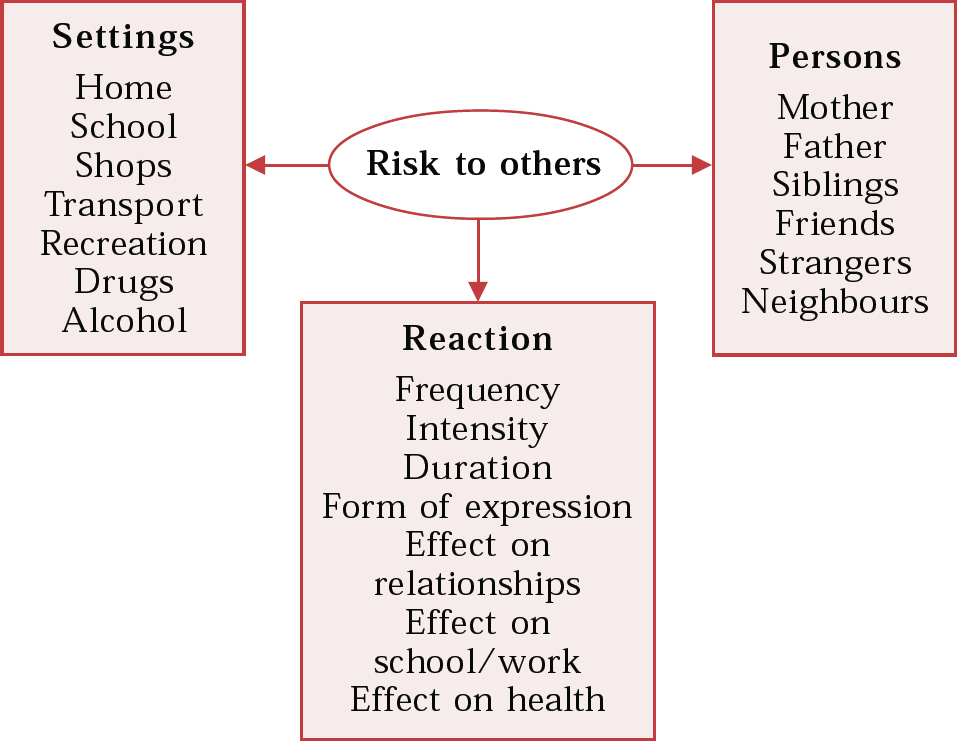

In assessment of young people in whom there is a risk of violence and mental health problems, certain key factors must be considered; these are listed in Box 2. When a young person has been assessed, it often becomes apparent that there are a number of overlapping risks (e.g. risk of harm to self, especially in male young offenders, can be lost in the level of concern about risk of harm to others). Practitioners should tease out these overlaps and state each risk as specifically and separately as possible. Risk should be predicted only for the immediate/short-term future. Regardless of the type of risk assessment used by the clinician, the multi-agency team needs to know the situational factors. Will the behaviour occur in the public/domestic domain, with/without provocation, in the immediate or extended vicinity? Will the victim(s) be perceived by the young person as vulnerable? Will the young person hold hostile attributions towards the victim? Will the victim represent certain meanings for the young person, e.g. authority figure, abuser, bully? Will the victim be in the immediate or in an extended vicinity? Who are the potential victims? (always list them). Does the young person lack concepts of emotion and/or lack safe problem-solving skills. Does the young person misuse substances, engage in other high-risk behaviour and is he/she easily provoked? (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Assessment framework

Box 2 Key assessment issues where there is risk of violence and mental health problems

Who does the assessment (do they have to be clinicians)?

Use of informants

How stable is the assessment – will it hold for months?

Reliability and validity

Difference between current symptoms and future risk of violence

Adolescent needs and risk assessment tools

General principles

Standard clinical assessment tools used in child and adolescent psychiatry cover many of the areas considered in forensic child and adolescent risk assessments (Reference Gowers and GowersGowers, 2001). This is especially important as juvenile justice systems in particular are not always equitable. In choosing between the many scales available it is important to question not just their proven scientific properties but also their feasibility for practitioners to use (given that resources available to CAMHS practitioners so often fall short of the ideal).

It is important to consider the purpose for which the scale be used (see Table 1). Scales that measure psychopathology may not be good ways of assessing the risk that the psychopathology poses. Measures used to map out types of symptom must have good content validity. An instrument required to pick out one group of symptomatic people from the rest of the community (e.g. mental health screening of young people in custody) needs to have good criterion validity. A related issue is the extent to which the scale is intended to measure change.

Table 1 Grid for specifiying requirements of a structured scale in a juvenile forensic population

| Assessment required (yes/no) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose of assessment | Psychopathology | Need | Risk |

| Screening of all juveniles coming into contact with an agency | |||

| Detailed assessment, e.g. for sentencing, planning treatment | |||

| Measuring change, e.g. during treatment or sentence | |||

What concept of psychopathology?

Is a broad or narrow approach to psychopathology needed? Child psychiatry already benefits from using multi-axial and developmental concepts of child psychopathology. Specific and general intellectual delays are very common among young people in the juvenile justice system, as is comorbidity of disorders. Broad-band interviews, however, offer only poor coverage of rare conditions such as pervasive developmental disorders.

Health needs assessment

Health needs assessment is an important contributor to risk management. Examination of health needs indicates management issues for the immediate, short- and long-term perspectives. Needs assessment has a theoretical base, provides a dimensional classification of need and defines the circumstances in which action is required. Different perspectives can be taken into account, for example those of the carer, the professional and the young person. Long-term, replicable qualitative and quantitative data can be provided across many settings: community, out-patient, in-patient, youth offending teams, residential care, open and secure and young offenders units. Where child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) are facing an influx of high-risk referrals, needs assessment can be used as a basis for multi-agency planning. Health needs assessment has a theory and methodology different from those of risk assessment; nevertheless, the two separate processes are intertwined.

Needs assessment may both inform and be a response to the risk assessment process. Repeated needs assessments may be termed ‘risk management’. The Salford Needs Assessment Schedule for Adolescents (SNASA; Reference Kroll, Woodham and RothwellKroll et al, 1999) has been developed for use with all adolescents, including those presenting with high-risk violent behaviour both in the community and in secure settings. It identifies 21 areas of potential need, covering material, familial, social, educational, psychiatric and psychological problems and includes violence and self-harm. In assessing the significance of each need and how it may be met by services, the SNASA can be used repeatedly over time and through placements.

Adult risk assessment tools are being modified for use in children and adolescents. The two main adult tools that have been adapted are the HCR–20 scale (Reference Webster, Douglas and EavesWebster et al, 1997) and the Hare Psychopathy Checklist (PCL; Reference HareHare, 1980). The HCR–20 now has an established version for boys under the age of 12, the Early Assessment Risk List EARL20B (Reference Augimeri, Webster and KeoghAugimeri et al, 1998). The Psychopathy Checklist – Youth Version (PCL–YV), which is a modification of the revised PCL (PCL–R; Reference Monahan and AppelbaumMonahan & Appelbaum, 2000), is undergoing continuing work and refinement (further details available from the author upon request). It should be noted, however, that the PCL–R and the PCL–YV were designed to assess the construct of psychopathy and not as risk assessment measures per se. The Structured Assessment of Violence in Youth (SAVRY; further details available from the author upon request) has its origins in the HCR–20. It is a 30-item scale designed as a general assessment of risk of violence in youths. It consists of three risk scales (historical, social/contextual and individual/clinical) and one protective scale. Both the SAVRY and PCL–YV are in their final stages of development.

In considering the use of the SAVRY and PCL–YV when they become available, practitioners need to look at a number of factors: the positives and negatives of the parent tools; the desirability of tools with cut-off scores; the developmental modification of such tools and their transposability from a US to a UK population; and, especially, their applicability to girls and to individuals from diverse ethnic backgrounds (Box 3).

Box 3 Factors to consider in modifying the HCR–20 for use with adolescents

Negative factors

Its retrospective application is ‘with hindsight’ and may not give a completely accurate picture

Its quantitative approach means that borderline symptomatology or behaviour must be classified

It does not consider the impact of ‘no formal diagnosis’

It does not consider the impact of either long-term hospitalisation or secure detention in relation to risk management

Positive factors

Consistency of information gathered

It provides quantitative data that can be checked out for interrater reliability

The process can be repeated over time to inform risk management

It can be used to examine policy and practice retrospectively

Administration is not time-consuming if the individual completing the form is knowledgeable about the client

It can be administered by both clinicians and researchers (with some clinical knowledge)

It considers current protective factors alongside high-risk behaviours

It provides historical, clinical and risk thresholds, thus maximising the assessment process

The HCR–20 was trialled in its original form with a national sample of young people (Reference Webster, Douglas and EavesWebster et al, 1997). It combines statistical data with clinical information in a way that integrates current and historical clinical variables and contextual or environmental factors.

Relevance of specific disorders to aggression and violence

Hyperactivity and attention disorders predispose to both antisocial behaviour in childhood/adolescence and antisocial personality disorder in adult life. Disinhibition, poor impulse control and educational difficulties are implicated in this risk. Some youths respond by seeking acceptance and feelings of mastery by joining delinquent groups. Affective disorders play some role in youth violence (Reference Pliszka, Stienman and BarrowPliszka et al, 2000). Depression in adolescence can manifest itself as anger, which in turn is correlated with aggression. Anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorders show raised rates in violent young offenders. Part of the pattern of stress reactions includes a heightened sensitivity to potential threat, which can in turn involve the risk of a young person acting explosively or unexpectedly. Psychotic disorders occur only infrequently (Reference Clare, Bailey and ClarkClare et al, 2000; Reference Kazdin, Grisso and SchwartzKazdin, 2000). Pre-psychotic problems, in the form of borderline and schizoid personality disorders, may be important because concomitant difficulties with interpersonal relationships play a role in violent behaviour patterns. Neurodevelopmental dysfunction may be relevant, by leading to impairments in a youth's ability to adapt to stress, to recognise the consequences of his or her actions and to exercise impulse control. Serious mental disorders may have similar effects.

Affective disorders

Depression is commonly present in delinquents. Clinic attenders with conduct disorder have rates of depression of 15–31% (Reference Goodyer, Herbert and SeckerGoodyer et al, 1997). As antisocial youths are generally viewed as difficult and disruptive, the risk is that depression will go unrecognised by non-mental health agencies. Where depression and conduct disorder coexist, risk of substance (especially alcohol) misuse is high in young male and female offenders. Young offenders with comorbidity for depression and conduct disorder are particularly vulnerable to suicide attempts. Mental health screening in the young offender population may also be important to ensure early detection of sub-threshold cases of mania, where there can be chronic and rapidly fluctuating symptoms of irritability, emotional lability, increased energy and reckless behaviours.

Early-onset psychosis

A prodromal phase of non-psychotic behavioural disturbance occurs in about half of cases of early-onset schizophrenia and can last between 1 and 7 years. It includes externalising behaviours, attention-deficit disorder and conduct disorder. Mental health screening should include a focus on changes in social functioning (often from an already chaotic baseline level) to a state including perceptual distortion, ideas of reference and delusional mood (Reference ClarkClark, 2001).

As in adult life (Reference Taylor and GunnTaylor & Gunn, 1999) most young people with schizophrenia are non-delinquent and non-violent. Nevertheless, there may be an increased risk of violence to others when they have active symptoms, especially when there is misuse of drugs or alcohol. The risk of violent acts is related to subjective feelings of tension, ideas of violence, delusional symptoms that incorporate named persons known to the individual, persecutory delusions, fear of imminent attack, feelings of sustained anger and fear, passivity experiences reducing the sense of self-control and command hallucinations. Protective factors include responding to and compliance with physical and psychosocial treatments, good social networks, a valued home environment, no interest in or knowledge of weapons as a means of violence, good insight into the psychiatric illness and any previous violent aggressive behaviour and a fear of their own potential for violence. These features require particular attention but the best predictors of future violent offending in young people with mental disorder are the same as those in the general adolescent population (Reference Clare, Bailey and ClarkClare et al, 2000).

Autistic spectrum disorders and learning disability

Autistic spectrum disorders are being increasingly recognised but are often overlooked in forensic groups. Their identification is critical to the understanding of offending, especially in adolescents with a learning disability. This is particularly so if an offence or assault is bizarre in nature, the degree or nature of aggression is unaccountable and/or there is a stereotypic pattern of offending. O'Brien (1996) and Howlin (1997) proposed four reasons for offending and aggression in autistic persons:

-

1. their social naivety may allow them to be led into criminal acts by others;

-

2. aggression may arise from a disruption of routines;

-

3. antisocial behaviour may stem from a lack of understanding or misinterpretation of social cues;

-

4. crimes may reflect obsessions, especially when these involve morbid fascination with violence – there are similarities with the intense and obsessional nature of fantasies described in some adult sadists.

Knowledge about criminal behaviour in young people with a learning disability is still developing (Reference HallHall, 2000). The clinical issues that arise concern the additional care needed in interviewing at assessment, as much as the possible special implications with respect to antisocial risk that arise from their cognitive level or profile. As with anyone else, associated psychopathology, life experiences and personal background should constitute part of the assessment.

‘Prodromal’ personality disorder

Models used to describe severe personality disorder in adults (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 1999) may also be applied to young people. Hare (1993) differentiated between ‘psychopathic personality’, characterised by an unemotional and callous interpersonal style, and ‘antisocial personality disorder’, in which the key elements are poor impulse control and antisocial behaviour. O'Brien & Frick (1996; Reference FrickFrick, 1998) argued that these two groups have a different aetiology. Christian et al (1997) described a group of children with a callous, unemotional interpersonal style, who lacked guilt and who did not show empathy or emotions. Box 4 lists various factors thought to direct the pathway to serious antisocial behaviour and interpersonal violence.

Box 4 Factors contributing to serious antisocial behaviour and violence (Reference Bailey, Smith and DolanBailey et al, 2001; Reference GarborinoGarborino, 2001)

Family features

Parental antisocial personality disorder

Violence witnessed

Abuse, neglect, rejection

Personality features

Callous unemotional interpersonal style

Evolution of violent and sadistic fantasy

People viewed as objects

Paranoid ideation

Hostile attribution

Situational features

Repeated loss and rejection in relationships

Threats of self-harm

Crescendo of hopelessness and helplessness

Social disinhibition in group settings

Substance misuse

Changes in mental state over time

Violence in the family

Violence witnessed by or perpetrated against the child

The theoretical work of the 1970s provided a framework for understanding the multiply determined nature of abuse and neglect (Reference Ammerman, Hersen, Ammerman and HersenAmmerman & Hersen, 1992). Ecological models were said to interact and converge to bring about family violence. This belief led to an increased interest in clinical assessment and treatment. The epidemiological research of the 1980s documented the widespread prevalence of child abuse, neglect, spouse battering, elder mistreatment and psychological abuse. This in turn fuelled the development and evaluation of interventions for both victims and perpetrators.

Predominant factors within families that contribute to longer-term aggressiveness and risk of violence have been clearly identified in child rearing and parenting styles (Reference Farrington and BoswellFarrington, 2000). Against a backdrop of multiple deprivation three key clusters emerge. The first is the presence of criminal parents and siblings with behavioural problems. In the second, the day-to-day behaviour of primary caregivers is one of parental conflict, inconsistent supervision and physical and emotional neglect, with little or no reinforcement of pro-social behaviours. The child learns that his or her own aversive behaviour stops unwanted intrusions by the parents/caregivers. Young people who assault others have lower rates of positive communication with their families. A third cluster of family factors linked with later violence in the child include cruel authoritarian discipline, physical control and shaming and emotional degradation of the child.

Where young people live in a culture of violence in their homes and neighbourhoods, school has the potential to offer positive outlets to satisfy needs for belonging and recognition and acceptance through non-violent means. Failure to achieve academic success, peer approval and satisfying interpersonal relationships within the school context creates additional stresses and conflicts, with increased likelihood of aggression and violence linked to competition for status and status-related confrontations with peers (Reference Laub, Lauristen, Elliot, Hamburg and WilliamsLaub & Lauristen, 1998).

Domestic violence remains one of the most pervasive social problems, affecting most of the population directly or indirectly (Reference BlacklockBlacklock, 2001). One in four women experience domestic violence at some time, and a study by the National Children's Homes Action for Children in 1994 found that 75% of mothers subjected to domestic violence said that their children had witnessed it (Reference BlacklockBlacklock, 2001).

Abuse of parents by children

There is remarkably little known or documented on children violent to their parents, which is surprising given the level of knowledge and concern about antisocial and violent behaviour committed by children in school or in the community. The abuse of parents (with the exception of the elderly and the extreme act of parricide) can at best be seen as underresearched and at worst as a taboo subject associated with a sense of shame that parents cannot protect themselves against the violence of those with whose care and protection they are charged.

Seminal work by Strauss, Gelles and Steinmetz dating back to 1980 (Reference Strauss and GellesStrauss & Gelles, 1990) estimated that 18% of children between the ages of 3 and 17 years carried out one or more acts of violence towards parents. The victim was most often the mother; the violence ranged in severity from 10% of children hitting or striking a parent, 7% striking a parent with an object, 1% severely beating a parent to 1% using a potentially lethal weapon.

What is known about children who are violent to parents? Adolescents who have assaulted peers, siblings, teachers and strangers are at increased risk of having assaulted or threatened to inflict physical violence on their parents. Children who inflicted physical violence on parents were described by Harbin & Madden (1979) as more often economically dependent, male and aged between 13 and 24 years. Adolescents who are violent to parents appear to straddle socio-economic groupings. Family dynamics provide the greatest insight into the evolution of this particular form of violence in children (Reference Harbin and MaddenHarbin & Madden, 1983). It is common to find that the parents of such children convey inconsistent values about aggression. Although severe child abuse in this group is unusual, parents who use harsh child rearing techniques are at increased risk of being victims of violence at the hands of their children. Role reversal between parent and child (parentification) takes place, to the extent that parental authority is given over to the child.

Parents tend to deny the seriousness of acts of aggression and violence displayed against them. In the clinical situation when a child is referred because of violent acts occurring in the community or school, parents will not always reveal a preceding or coexisting history of violence in the home.

Violent assaults against parents are most likely to occur in the context of parenting stress arising from parent–child disagreement. Failure to set consistent limits on unacceptable behaviour produces a dynamic in which the child experiences an evolving sense of empowerment and, indeed, a sense of justification in dealing with increasingly failing attempts at parenting by escalating both the frequency and severity of violent responses. The tyrannical child is rewarded and reinforced in this behaviour by the parents giving in to this graded continuum of physical aggression.

The evolution of parental inconsistency and loss of authority that includes fear of the child can be likened to the need to maintain relationships through co-dependency as seen in adult male-to-female domestic violence. In domestic violence, the violence and abusive behaviours are used to control. The abusive behaviour is also used to support the sense of entitlement that allows an adult male to see his behaviour as reasonable given his partner's ‘unreasonable’ resistance to his expectation. This further fuels the process of partner blaming (Reference BlacklockBlacklock, 2001). Whatever other factors place a child at risk of being violent, this sense of entitlement and experience of being in control can lead to aggression and violence becoming the child's normal form of social transaction in the home and then beyond.

Theory into practice

Using a semi-structured approach to assessment of violence

Assessment of violence, in its various settings, degrees of severity and the presence or absence of mental disorder, must be approached systematically. Again the adult literature may be called upon, as it contains graded series' of questions that may be used with children and adolescents to ask about their violence (Box 5). By first giving the young person the opportunity to talk about violence done to him or her, whether at home, at school or in the community, the clinician will be able to gain an informed understanding of why this child is presenting at this time with this particular violent act (Reference Sheidow, Gorman Smith and TolanSheidow et al, 2001). The same structure can be used to take a history from parents, allowing them to explore with the clinician the depth and extent of violence displayed towards them behind the closed doors of home.

Box 5 Assessment questions to ask the child or adolescent

For each question, the young person says if and where the behaviour has happened – at home, at school or in the community

Has anyone ever thrown something at you?

Have you thrown something at anyone else?

Have you pushed, grabbed, shoved anyone?

Have you slapped anyone?

Have you tugged or pulled at anyone's hair?

Have you bitten anyone?

Have you punched anyone?

Have you kicked anyone?

Have you head-butted anyone?

Have you kneed anyone?

Have you ever put anybody in a headlock?

Have you ever held onto anyone around their neck so that they might be starting to choke?

Have you threatened anyone with a knife or any other object or weapon?

Have you used a knife or other weapon?

Have you done anything else that might be considered violent?

Interviewing a young person

Even with the prospect in the near future of a full set of gold-standard risk assessment tools for children and adolescents, the reality remains that the clinician often must interview a young person who is reluctant to be seen. The young person may have grown to view him-/herself as a constant focus of complaint, criticism and blame, ‘assessed out’ by a range of professionals, and skilled in the avoidance techniques of passive or overt hostility. This can make safe engagement a daunting prospect.

Complex cases take time, and regardless of requests for a ‘quick-fix’ risk assessment, the CAMHS team should carefully think through how to approach any assessment. Some general principles of risk assessment are outlined in Box 6and discussed below. The team should insist that all known information is provided and that the referrers are open and honest about the purpose of the assessment. Where possible, the team should provide the young person and the family with user-friendly information about the service and the assessment process. In an emergency, whether in a clinic, the home, a police station or residential open or secure facility, the team should insist that, as far as is possible in any crisis, its own emotional and physical safety and those of other professionals and the young person are assured. In no circumstances should an individual enter a situation alone without immediate back-up.

Box 6 Some general principles of managing risk in adolescents

Gather information from several sources

Accept that risk cannot be eliminated or guaranteed: it is dynamic and must be reviewed frequently

Throughout the process, be clear about the exact role of each member of the child mental health team and have clear channels of communication within the team

Where there is multi-agency involvement in the process, decisions should not be made by one person alone (a common pressure placed, in particular, on the child psychiatrist)

Some risks are general, others are specific and have specific victims

Outcomes must be shared but within the boundaries of ‘need to know’ and level of confidentiality expected

It seems likely that CAMHS teams are to be increasingly asked to undertake risk assessment. When the risk behaviour is that of violence, health service managers must themselves make an adequate ‘risk assessment’ of the physical circumstances in which the CAMHS team will work. They must also ensure that all staff have appropriate training not only in child and adolescent risk assessment but also in self-protection – as a minimum, in disengagement techniques.

In an emergency assessment it is vital to stress that any examination can provide only a ‘here and now’ snapshot of the young person, who is often highly aroused because of the emotional crescendo surrounding him or her. The latter is all too often a response to the fear and sense of hopelessness, helplessness, frustration and, at times, anger that the young person's behaviour has engendered in carers, who may be emotionally and physically exhausted and feel unsupported.

Allowing the young person to (a) state his/her own list of percieved problems and (b) state an opinion on the list of problem behaviours adults believe he/she is demonstrating, can, whether at interview resulting in a long silence or verbal abuse, allow the young person to have a voice in his/her own assessment. This can at least in some cases allow the young person to use the assessment constructively. At the outset it is essential to make clear the boundaries of confidentiality, which by the time a crisis is reached, may mean that much of what is said by the young person has become ‘need-to-know’ information (Reference Bailey and CordessBailey, 2001).

In most cases, the young people can sustain interview and start to share with the interviewer their account of the escalation of violent behaviour. At each stage ask the individuals what they think and feel and about accompanying physiological experience. Start with injustices and acts against them and then what they have done to others. A systematic approach avoids the pitfalls of stereotyped beliefs about types of violence committed by boys and girls and opens up issues of violence against and by children in the family home. It exposes those children who have genuine difficulty linking thoughts, feelings and the physical responses of their bodies when experiencing sadness and anger under varying levels of stress and/or when the end result is violent behaviour. It therefore offers a more complete picture of the young person's behaviour, and the assessment can then inform not only treatment choices but how delivery of treatment may need to be modified for the individual child.

This process takes time but it has the added advantage that during assessment the young people start to gain insight into themselves, which can enable them to be open about their fear, or indeed lack of fear, of their potential to commit more serious acts of violence in the future. This approach has been adopted by the Forensic Adolescent Community Team Service (FACTS) in Salford to address risk of violence, and similar systematic approaches have been used with children involved in substance misuse, criminal behaviours and fire-setting and with children who are sexually abusive. When combined with holistic needs assessment, complex cases can start to be broken down into constituent components, which can be addressed by different parts of the multi-agency services involved, utilising a Care Programme Approach (CPA) and social services care planning. The developing adolescent risk assessment tool derived from the HCR–20 sits well with this approach, as its risk component has similarities to the CPA. Key to safe assessment is bringing the young person actively into the process from the outset. CAMHS are skilled in the art of clinical engagement and this ultimately is most likely to increase the effectiveness of an informed-needs-led multi-agency response to risk.

Conclusion

Risk assessment and management of violent children must be informed by those with expertise in and understanding of child and adolescent development. CAMHS therefore have an important role to play, a role that is likely to increase and has particular importance if the young person has special needs and/or recognised mental health problems. To fulfil this role safely, practitioners must be equipped with appropriate training and a framework within which to carry out assessments before advising on and being involved in treatment. This inevitably has implications for workforce, recruitment, retention, training and resources. Risk assessment and management of violent children will need to be incorporated into any child and adolescent mental health clinical governance framework both now and in the future.

Multiple choice questions

-

1. Principles of managing risk in adolescents include:

-

a ensuring that risk is eliminated

-

b identifying one person to take all decisions alone

-

c taking into account that risk is dynamic

-

d collecting information from social services alone

-

e ensuring that each risk is stated separately.

-

-

2. When carrying out risk assessment:

-

a prediction is for all types of violent behaviour

-

b prediction is over a set period

-

c violent acts must be detectable and recorded

-

d base it on information from a single informant

-

e use well-defined published schema.

-

-

3. In early-onset psychosis the risk of violent behaviour is raised when there are:

-

a misuse of drugs or alcohol

-

b no fear of imminent attack

-

c persecutory delusions

-

d no interest in knowledge or use of weapons

-

e a valued home environment.

-

-

4. As regards assessment tools:

-

a good measures of psychopathology are good measures for assessing risk

-

b broadband interviews offer good coverage of rare conditions

-

c health needs assessment defines circumstances in which action is required

-

d health needs assessment cannot be used over time

-

e the HCR–20 can be used over time to inform risk management.

-

-

5. Risk of violence by a child to a parent (or primary adult caregiver) is raised when:

-

a parents convey inconsistent values about aggression

-

b parents use harsh child rearing techniques

-

c role reversal between parent and child occurs

-

d assaults occur in the context of parenting stress

-

e parents tend to deny the seriousness of the child's violence against them.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | T | a | F | a | T |

| b | F | b | T | b | F | b | F | b | T |

| c | T | c | T | c | T | c | T | c | T |

| d | F | d | F | d | F | d | F | d | T |

| e | T | e | T | e | F | e | T | e | T |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.