As mentioned in our previous article (Reference Martindale and SummersMartindale 2013), the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2009) suggests that psychodynamic principles can help psychiatrists to understand the experience of people with psychosis. In this article, we hope to show the feasibility and benefit of using psychodynamic principles as part of case formulation.

Varieties of formulation

Formulations are an attempt to explain or understand, a way of making sense of things. They are hypotheses or tentative ideas, not statements of knowledge. A formulation brings to the foreground thoughts or chains of thought which will influence how people are approached and communicated with, and may sometimes also guide treatment in a more formal way.

Formulations can be about a problem or predicament for a patient, a family, a care team or an organisation, for example they can be about the development of psychotic symptoms and experiences, about coping with a serious illness, about difficulties in engagement or managing risk, or about conflicts between different parts of an organisation.

Formulations can be developed in different ways. They can result from an individual or a group process, and they may or may not be written down. They may be the product of conscious reflection or a semi-automatic process. To some extent, practitioners and patients try to explain and understand (formulate) thoughts and emotions all the time. They may or may not do this openly or jointly.

There are many different models, theories and frameworks for the making of formulations, and a psychodynamic approach can be used alone or in conjunction with other approaches. Distinguishing features of a psychodynamic approach include:

-

• the underpinning theoretical framework recognises the importance of unconscious processes

-

• specific approaches are used to elucidate interpersonal and unconscious processes, for example attention to transference and countertransference, to associations with the patient's story and to boundaries of the space for dialogue (Box 1). Most importantly, there is a search for repetitive patterns in relationships.

BOX 1 Some psychodynamic terms

Transference and countertransference

Transference is the human tendency for people to experience and treat relationships in line with their internal models of ‘how particular relationships work’. Countertransference refers to the feelings and relationship evoked in response to a patient's transference-based words, emotions and behaviour (e.g. case vignette 1).

Associations

Thoughts and feelings that occur in healthcare professionals in the course of thinking about or discussing something that may in some way be a response to this ‘thing’, even when the links are not immediately apparent or conscious (case vignette 2).

Boundaries

Boundaries here relate to time, place, structure and role e.g. for a team discussion of formulation, there may be an allocated time, room, format, and a set of expectations of participants. Importance of clear boundaries:

-

• creating conditions that promote psychological security, to encourage freedom of exploration

-

• offering a potential additional source of information about the patient – when there is pressure to alter boundaries either from the patient themselves or from the responses of practitioners to the patient.

The psychodynamic approach to formulation discussed in this article is applicable to any psychiatric problem, not just psychosis, although our examples and discussion of the value of formulation relate specifically to psychosis. Patients with psychosis differ in the extent to which psychological factors contribute to the development and maintenance of their psychotic symptoms. Psychological formulations may at first sight appear most relevant in forms of psychosis where emotional factors seem prominent. However, psychological factors are important in every individual with psychosis, including where neurodevelopmental factors seem dominant (see case vignette 4). For everyone they shape experience, behaviour, relationships and responses to illness and treatment. Psychodynamic approaches are likely to be particularly helpful in understanding patients' relationships, family dynamics and interactions with services as well as psychotic symptoms. In our experience, practitioners tend to find formulation most helpful, both for themselves and their patients, in situations where they feel worried, are short of ideas about what to do or have difficult countertransference responses.

Case vignettesFootnote a

Vignette 1: Transference, countertransference and repeating patterns

Rachel started to hear a critical voice shortly after she had left a job where she felt bullied and had had various disputes with colleagues. She believed the voice belonged to her stepfather who had sexually abused her as a child. Rachel's community nurse felt increasingly annoyed by the way Rachel treated her, for example at every visit, she would take 10 or 15 min to make a drink for herself or finish a telephone call, then would spend the rest of the session criticising relatives or friends, ignoring the nurse's attempts to introduce other topics.

The dismissive, contemptuous way Rachel treated the nurse seemed rather like the way the voice was treating Rachel and like Rachel's account of the way she had treated her colleagues, suggesting that this might be a transference pattern. The nurse's annoyed response to Rachel's self-centred behaviour (her countertransference) seemed to parallel Rachel's feelings about her hallucinatory voice and her work colleagues. These repeating patterns formed the basis for a formulation. This hypothesised that one effect of Rachel's experience of abuse is that she has internalised a model of relationships where one person exploits and mistreats another, and has herself taken on (identified with) aspects of her abuser. The suggestion was that in her psychosis, these abusive aspects are experienced in the voice and in imagined persecutors rather than within herself.

The context of formulating

In a female acute ward, staff were under increasing pressure to reduce bed use, and there was a strong subgroup among the staff who believed the pressures were due to inappropriate admissions of people who were ‘just attention-seeking’. Rachel was admitted here after a later relapse. She was contemptuous and sullen with the admitting doctor (who was exhausted and long past the end of his shift) and he concluded that her threats of suicide were ‘manipulative’. Later when the doctor had read Rachel's notes, had had a less hurried conversation with her and had talked to her nurse, he changed his view, and thought now that her self-harm had been a response to distressing persecutory hallucinations.

For this doctor the context in which he made his formulation had a big impact on his hypotheses at different points.

Vignette 2: Structure for formulation discussions, use of associations

A few days after the birth of her first baby, Jane developed delusional ideas that at the delivery a demon had been planted inside her so that her mind and actions were now being controlled by demonic powers, which she could hear discussing her and telling her to kill the baby. She became terrified that she would harm her daughter. Although now much improved, she was isolated and not enjoying motherhood. The team discussing her formulation had many ideas for addressing her social isolation and they almost moved straight to discussing these. However, they did decide to stop and reflect first. (Their shared understanding of the importance of structure for formulation discussions helped here.)

Initially, there seemed little more to say, then a new theme emerged. The support worker started talking about a different patient who had been isolated because of her mother's behaviour (an association to Jane's case). She then remembered that she had found Jane's mother's attitude unusual in a rather ill-defined way, perhaps rather disengaged. The care coordinator then started to muse on how superficial Jane's account of her childhood had seemed. The junior doctor remembered that Jane had had a delusional idea about the baby actually being her mother, and also that Jane's mother had had long periods of depression during Jane's childhood. This led to hypotheses that for Jane the birth of her baby had stirred up feelings about her relationship with her own mother, including feelings of not being cared for emotionally, and resentment at this. The team thought it was these unacknowledged feelings that had led to the delusion where the baby who needed so much care was misidentified as her mother, felt to be starving Jane herself of care, and hence the baby (mother) became the object of murderous rage.

Sharing the formulation with the client

This care coordinator then talked with Jane about how her mother's depression had affected her and about their current slightly tense relationship, although she chose not to mention that the support worker had thought her mother's behaviour unusual, or that the team hypothesised that Jane might feel quite angry with her mother (although this gradually emerged through Jane's own reflections). The care coordinator shared only selected parts of the formulation discussion.

The discussions about the formulation led to changes to the management plan. The team recognised that Jane was already actively reestablishing social networks, and decided against allocating a support worker. Instead, a series of additional family meetings were arranged. Practitioners helped Jane and her mother to start to discuss some of Jane's long-standing resentments about her mother's reliance on her, which in turn led to a new warmth in their relationship.

Vignette 3: Boundaries, collateral information and countertransference

Several people in a group who were normally very punctual came late to a meeting to discuss a formulation for Emma. The care coordinator then suggested that perhaps the discussion was not really needed after all, as it seemed clear to her that Emma had become psychotic in response to her ex-boyfriend's suicide. The team discussed the late start and the care coordinator's comments. They then started to recall other ways that practitioners had subtly avoided being with or thinking about Emma, for example the psychologist had delayed rearranging a cancelled appointment, the care coordinator had suggested that she could be a good patient to transfer to a new team member. The notes contained virtually no information about the suicide. The care coordinator said that at their first meeting Emma did not mention the suicide at all, and she only learned about it later through Emma's mother. The team then hypothesised that the tragic event had been so unbearable as to be literally ‘unthinkable’ and that the thoughts and feelings about it had emerged in psychosis (where Emma had developed the delusional belief that her ex-boyfriend was still alive). This formulation generated some new ideas about how the team might work with Emma.

Here, practitioners' countertransference responses to the patient of ‘avoiding thinking’ had influenced their behaviour in another setting – a ‘parallel process’ to Emma's. This might have been harder to notice if the team had not had a pattern of attention to boundaries and thus been able to notice pressures to change these.

Vignette 4: Psychosis without obvious psychological origins

Stephen had prominent negative symptoms, made little spontaneous conversation and responded to his social worker mainly in monosyllables. In a team meeting, the social worker explained that although the norm for the team was weekly visits, in this case he had reduced visits to once a month. It emerged that the care coordinator had not offered Stephen several of the team's standard interventions, such as working on a timeline of his life and a genogram. Visits had become limited to questioning about his medication and his (limited) daily activities. Other team members spoke of their own experiences with clients where they had felt that they had little to offer, but where they had been surprised to learn how much the clients still seemed to value the relationships. The social worker hypothesised that his withdrawal from more detailed work with Stephen might in some way be a response to his own feelings of despondency and uselessness, rather than an appropriate response to Stephen's needs. He decided to reinstate weekly visits, plus occasional joint meetings with Stephen's family. A year later, although conversation was still difficult for Stephen, he had slowly begun to confide about some things that were clearly important to him, and was beginning to participate more in family life. The team commented on how the social worker's conversation about him seemed much warmer and more interesting.

Although the team believed that Stephen had a predominantly neurodevelopmental psychosis, they still found the psychological formulation helpful.

Steps to a psychodynamically informed formulation

1 Identifying what needs to be understood and assembling information

This includes information about the patient's life, relationships, traumatic experiences and the content of their psychotic experiences (Box 2).

BOX 2 Headings for gathering information for formulation of an individual's psychosis

-

1 Problems for formulation – why is this person/issue being discussed now?

-

2 Outline of life history, attending carefully to each stage of life (0–5 years, 5 years– puberty, adolescence, early adulthood, each decade of adult life) and for each of these covering biological factors, events, relationship patterns, trauma, problematic situations, and symptoms. It is important throughout to attend to feelings evoked and instances where feelings might be expected but seem to be missing

-

3 Events and circumstances around the time the problem developed

-

4 Contents of symptoms (e.g. hallucinatory figures, psychotic beliefs)

-

5 Current life circumstances and relationships

-

6 Relationships with practitioners and treatments

-

7 Hypotheses (see Fig. 1 for ways of structuring this)

-

8 Implications for the person's interaction with practitioners

-

9 Implications for action

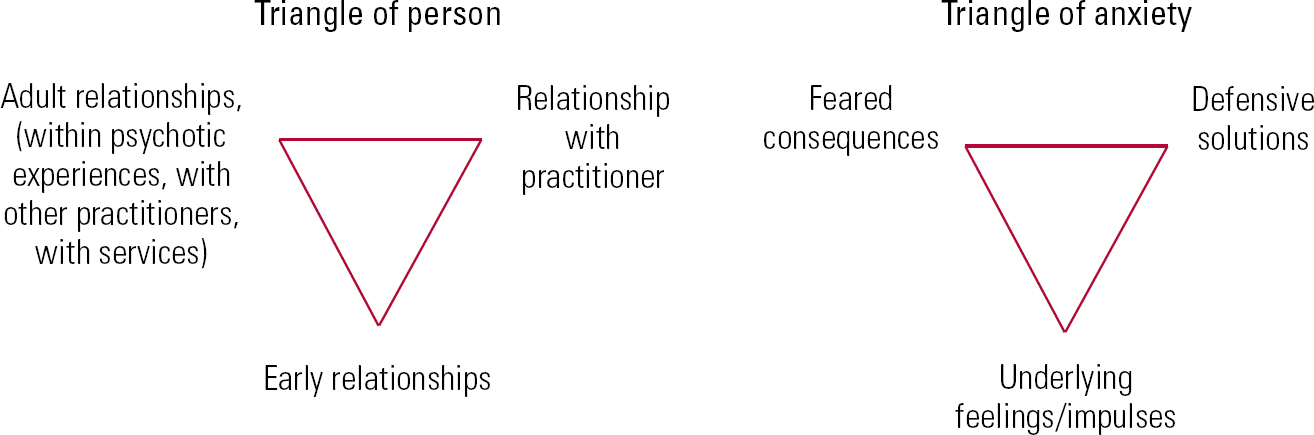

FIG 1 Malan's triangles. Adapted from Reference Malan and Coughlin Della SelvaMalan & Coughlin Della Selva (2006).

What should be recorded? When a formulation has been worked on without the patient present, there are some particular issues about what should be recorded, given that the discussion may have covered practitioners' feelings. One approach is to record only hypotheses.

Collateral information is often crucial. A psychodynamic perspective includes the idea that psychosis may result from unbearable affects (Reference Martindale and SummersMartindale 2013), and that therefore the patient's own account may omit crucial aspects of what has made them ill in order to keep the affect out of awareness (see case vignette 3).

In contrast to other approaches, a psychodynamic approach pays particular attention to past and current patterns of relationships, to relationships with practitioners and services, to practitioners' countertransference, and to information emerging in the course of discussions, such as associations and pressures on boundaries. It can be helpful to attend to aspects that seem surprising or puzzling, a burden or anxiety-provoking.

2 Reflection

This involves reflecting on both available and missing information, including missing emotion. This means resisting pressures to move straight into suggestions for action.

3 Developing hypotheses

Developing hypotheses and considering how these may relate to the presenting problems. A narrative about these can be structured in various ways (see the next section).

Considering implications of the hypotheses

This may include implications for care planning by practitioners, such as predicting what may influence the risk of relapse, suggesting interventions which may help support the patient's non-psychotic functioning, and identifying patterns of interaction that practitioners may be drawn into and how it may be helpful to respond to these. If a formulation is worked on without the patient, then consideration needs to be given to what ideas might usefully be offered to the patient for their reflection. The patient's own formulation of their experiences is of course of great importance in determining how they feel about these and what actions they take, and careful thought needs to be given to how this will interact with the formulation of the staff. In some situations, it is very unhelpful for practitioners to share a formulation which differs from a patient's own. The formulation itself may give clues to this. For example, in case vignette 2 the team hypothesised that Jane had found it impossible to tolerate her anger at her mother. They thought therefore that to insist to Jane that this was an important aspect of her problems might well be very disturbing for her. In some situations, the patient's responses to a gradual discussion of formulation will be a guide to where it is helpful for the discussion to go. For example, it is highly unlikely to be constructive to proceed with a line of discussion which arouses reduced rapport, marked anxiety or intensification of psychotic thoughts or experiences.

A framework to structure the formulation

A team may find it helpful to have a shared framework for formulation. Psychodynamic approaches to formulation are described in detail elsewhere (Reference Mace and BinyonMace 2005, Reference Mace and Binyon2006). We will consider here three generic formulation frameworks, and then one that is more specifically psychodynamic. All of these can be used in any context, regardless of the presence or absence of psychosis.

Structuring the formulation – the PPP framework

A generic framework can be useful, particularly if practitioners come from different theoretical backgrounds. A familiar generic approach is to structure hypotheses around the stress–vulnerability model (Reference Zubin and SpringZubin 1977), considering predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating (PPP) factors. With a psychodynamic perspective, attention will be paid to how these factors link together, for example why the precipitating and perpetuating factors have the effect they do – i.e. their specific dynamics and meaning for this particular individual (e.g. in terms of their personal history). Perpetuating factors considered may include patterns of interaction that staff may be drawn into (e.g. the irritation of the nurse treated abusively by Rachel in case vignette 1).

For Rachel, predisposing factors included her sexual abuse and a strained relationship with her mother, whom she described as cold and strict. A major precipitating factor was the dispute at work, which left her feeling bullied. One perpetuating factor was the fact that having lost her job, she was spending much more time with her mother and finding this difficult.

Structuring the formulation – vulnerabilities and defences

A second generic approach is to consider underlying vulnerabilities and defences (coping strategies), attending to how things may feel to the patient, what has not been bearable, and to non-psychotic as well as psychotic defences.

One important hypothesis about what had been unbearable for Rachel is her experience of being abused, including being exploited and having her own needs dismissed. One of her non-psychotic coping strategies seems to have been ‘identification with the aggressor’, that is unconsciously adopting some of the qualities of her abuser so that she is now often in the neglectful and bullying position rather than being bullied (the annoyed feelings of the care coordinator related to being on the receiving end of this). In her psychosis, the bullying aspects of self are denied and projected into the hallucinatory voice and her imagined persecutors.

Structuring the formulation – increasing or decreasing inner security

A third generic approach involves structuring the account around factors that increase or decrease inner psychological security (Reference ThorgaardThorgaard 2009).

Some things are likely to increase psychic security for all of us – for example, feeling physically safe and well, having a home, a role in life, and caring relationships. Similarly, for all of us there are things likely to make us feel less secure and more in need of defensive solutions – for example, being disliked, criticised or losing a job. For Rachel, there are some factors more specific to her. For example, she is likely to feel more secure while able to use her non-psychotic defence of being the bully rather than bullied (so long as this does not cause her new problems). Conversely, her security is likely to be threatened by things that trigger feelings of being a victim again.

Structuring the formulation – using Malan's triangles

A more specifically psychodynamic framework is to look for repeating patterns in the person's relationships. Reference MalanMalan (1979) offered a model for this in his ‘triangle of person’ (Fig. 1). In a psychodynamic view, repeating patterns are understood to occur because they reflect something the person brings to their relationships, based on internal expectations, needs and internal object relations. Therefore parallels are likely to be found between the triangular patterns of early life relationships, adult relationships and the observed relationship with the practitioner. It is helpful to look for a further triangular pattern in what it is the person seems to seek in relationships, the responses they receive and how they themselves then react to these responses. People may have different patterns depending on whether they are dealing with men or women, authority figures or people offering care. Relationship patterns offer clues to the person's strategies for managing life and relationships and Malan's ‘triangle of anxiety’ offers a model for summarising these. It draws attention to how relationship patterns may reflect defences /protection against the feared consequences of underlying feelings and impulses.

For Rachel, in the triangle of person, there are parallels between her early relationships (victim–abuser), her adult relationships with her hallucinatory voice (victim–abuser) and her perceived relationship with work colleagues (victim–abuser), her reported aggressive behaviour to work colleagues (abuser–victim) and her relationship with her care coordinator (abuser–victim). In the triangle of anxiety, underlying each of these relationships, defensive aspects seem to include the non-psychotic defence of identification with the aggressor, and the psychotic defence of projection of the aggression into a hallucinatory figure. We hypothesise that what drives the need for these defences is a longing for relationships with others but a fear that this will lead to her feeling unbearably abused and disregarded.

Finally, a psychodynamic perspective can also be used to enrich a narrative about the meaning of symptoms which has already been structured by a different theoretical model, such as a cognitive–behavioural, cognitive analytic or systemic one.

A process to support good formulation

The process of creating the psychodynamic formulation is important. It needs to support practitioners to be as open as possible to the experience of the patient, and to think flexibly and creatively. Those making a formulation will naturally be drawn to the ideas most readily accessible to them, particularly so if they are anxious and short of time. Which ideas are most accessible will be determined in part by the social and cultural context, and in part by transference and countertransference pressures.

In a psychodynamic approach, three key features help to mitigate against such biases: a tentative attitude, a space for reflection and different perspectives. Aspects of these are shared with other approaches to formulation.

A tentative attitude

Treating formulations not as knowledge but as hypotheses implies expecting to review and revise them as new information emerges. Crucial to this is ‘negative capability’ (Reference BionBion 1992) – being able to tolerate not knowing. Practitioners need to be reflective about their own biases in developing a particular formulation, considering the influence of their social and cultural context, personal interests, countertransference and power relationships. In a group discussion, different people may have a different sense of what hypotheses feel most useful, and there needs to be space for this, particularly when working jointly with patients and families. For instance, in case vignette 2, the idea that Jane herself seemed to find most helpful was the simple notion that how she felt now might have some connection with her own experience of being mothered, and in conjunction with this she started to feel much more curious about her daughter's thoughts and feelings.

A space for reflection

This is about having enough time and freedom from immediate practical and emotional demands. In a group or supervision setting, boundaries are an important aspect as predictability in time, place, roles and people involved helps to create a sense of security to support exploration away from habitual comfort zones. Sometimes it will be easier to think more freely away from the patient than with them. In case vignette 1, when Rachel's care coordinator was with Rachel she felt preoccupied with the struggle to conceal her own irritation and had found it hard to think about Rachel as vulnerable, but this changed as she started to develop a different understanding of Rachel's behaviour in the discussion with the team.

Different perspectives

Unrecognised countertransference responses can distort the formulation (e.g. when Rachel's care coordinator had felt that the main problem was Rachel's aggression and self-centredness). Discussion with others not directly involved in the relationship can be helpful in clarifying these patterns. One of the things that helped Rachel's ward doctor start to think about her differently was hearing from the care coordinator and primary nurse how very differently they felt about her. In a group discussion, although it is possible for everyone to be caught up in a similar countertransference position without recognising it, there is nevertheless more chance of a range of perspectives being available, so it is important that everyone's contributions are considered, regardless of their training or experience. Good supervision is particularly important for practitioners with limited psychodynamic training. Psychodynamic training can help, as a central part of this is increasing awareness of one's own inner world and developing ability to access to ‘a third position’ or ‘internal supervisor’.

What resources are needed?

Organisational and management support is crucial. This needs to include recognition that time for reflection is a legitimate and important part of mental health work, so that time allocated for formulation is not constantly eroded by other priorities. This is not necessarily expensive, as it may well avoid professional time being wasted through the team identifying unhelpful or unnecessary interventions (see case vignette 2).

Incorporating a psychodynamic perspective requires sharing of theoretical knowledge. All teams are likely to have this to some extent. Even where there is no psychodynamically trained practitioner, many psychiatrists and clinical psychologists will have gained basic understanding of psychodynamic principles through their professional training.

For group discussions of formulation, it will be helpful to agree on using psychodynamic perspectives, to be clear about the purpose and structure of the discussion and to appreciate the value of considering countertransference responses, of sharing associations that may not feel immediately relevant and of listening to contributions from all participants regardless of their expertise. It may be helpful, but is not essential, for participants to have some theoretical knowledge of psychodynamics. Participants without psychodynamic experience may find it helpful to begin to learn about this by developing formulations jointly with more experienced practitioners. In groups where participants are not accustomed to a psychodynamic approach, leadership from a psychodynamically trained practitioner is helpful.

Where practitioners themselves have some training in psychodynamic work, a psychodynamic approach may be incorporated readily, even automatically, in everyday practice and without extra cost.

The resources needed are within the reach of ordinary National Health Service (NHS) multidisciplinary teams and need not be greater than for other approaches to formulation. The literature contains some accounts of where this is happening (Reference DavenportDavenport 2002), and Box 3 lists ways in which psychodynamic thinking has been incorporated in everyday practice of busy teams.

BOX 3 Examples of where psychodynamically informed formulation contributes to general clinical care in busy multidisciplinary teamsFootnote a

Informal uses (where the practitioner's thoughts on the formulation are not necessarily written down or explicitly articulated)

-

• In discussions with clients, e.g. about how they make sense of their symptoms or about relapse prevention in the course of routine psychiatric appointments

-

• In family discussions, e.g. on similar topics, again in the course of routine appointments

-

• In recommending individual treatment plans

Explicit formulation (although not necessarily involving use of psychodynamic terminology)

-

• In communication with other professionals, when comments on diagnosis are supplemented with comments on what may have contributed to the development and maintenance of the person's problems

-

• In ‘formulation discussions’ – multidisciplinary discussion where professionals meet to develop a formulation and consider implications for action. Typically 1 hour long, and usually there are concerns about a client's progress or the therapeutic relationship

-

• In clinical supervision, particularly when considering the therapeutic relationship or deviations from a practitioner's usual practice

a These examples are taken from services where we have worked.

Is it worth trying to incorporate psychodynamic understanding?

Criteria suggested for evaluating the appropriateness of formulations include whether they fit the evidence, avoid leaving important things unexplained and make theoretical sense, in addition to whether they can be used to make predictions or plan interventions and what happens when these are used (Reference Johnstone, Johnstone and DallasJohnstone 2006).

There are strong theoretical and empirical arguments for including psychosocial elements in formulation in psychosis. The way professionals make sense of people's experience of psychosis determines their behaviour, the interventions they consider relevant and their ability to feel empathy, hope, confidence and a sense of alliance with the patient (Reference Johnstone, Johnstone and DallasJohnstone 2006; Reference SummersSummers 2006; Reference TarrierTarrier 2006). For patients, formulations which view psychotic experiences as meaningful and related to their life story are more often in line with their own views – more acceptable, and associated with less stigmatising attitudes and greater motivation to recover (Reference Angermeyer and KlusmannAngermeyer 1988; Reference Walker and ReadWalker 2002; Reference Geekie and ReadGeekie 2009; Reference Stainsby, Sapochnik and BledincStainsby 2010). Having a psychiatrist who treats the content of their subjective experience as relevant seems to be associated with improved satisfaction, therapeutic alliance, medication adherence and outcome (Reference McCabe, Heathe and BurnsMcCabe 2002; Reference Priebe and McCabePriebe 2008). Thus, although it is common among psychiatrists to regard psychosis, particularly schizophrenia, as primarily biological, overlooking psychosocial components will have unintended adverse effects.

There are strong theoretical arguments why a psychodynamic perspective is likely to add to other psychosocial perspectives. It offers an additional and complementary viewpoint, which is important as needs that are not easily recognised from one perspective may be better highlighted from another. A psychodynamic perspective is likely to be of particular value in understanding the interpersonal relationships which are likely to be central to patients' recovery, family relationships and use of services, and in developing therapeutic relationships which are better able to support all aspects of care. Particularly because of its emphasis on relationships, psychodynamic formulation may benefit both clients and practitioners. It can benefit clients by influencing care plans, therapeutic relationships and the acting out of countertransference (case vignette 4), and practitioners by helping them feel more able to tolerate difficult countertransference responses (case vignettes 1 and 4) and to think creatively (case vignettes 1–3).

Although there are no randomised controlled trials of bringing a psychodynamic approach to formulation in everyday clinical care, there is empirical evidence of the value of this practice. This comes from reports of the perceptions of practitioners using these approaches (Reference DavenportDavenport 2002; Reference SummersSummers 2006; Reference Martindale and SmithMartindale 2011) and from outcome studies in mental health services where psychodynamic principles are used routinely to try to understand patients' difficulties (Reference Aaltonen, Seikkula and LehtinenAaltonen 2011; Reference Seikkula, Alakareb and AaltonenaSeikkula 2011). There is also growing evidence of the value of psychodynamic formulation from therapies that use this (Reference Summers, Rosenbaum, Read and DillonSummers 2013). Although the evidence for these therapies in psychosis is still much less extensive than that for cognitive–behavioural therapies, there is no evidence that, in the context of general clinical care, cognitive–behavioural formulations are more reliable or valid than those based on psychodynamic models, or that any one approach to psychological formulation is superior to others (Reference Johnstone, Johnstone and DallasJohnstone 2006).

Last, arguments against using a psychodynamic approach are still frequently based on unsound information (Box 4).

BOX 4 Psychodynamic approaches: five myths challenged

MYTH: Using psychodynamic principles is incompatible with modern understanding of the biology of psychosis

FACT: A psychodynamic perspective on psychosis accommodates the biological evidence without difficulty. It takes biological predisposing factors as one possible component of vulnerability, although without regarding these as always primary, dominant or necessary. It acknowledges the brain as the substrate for all experience, although not necessarily as the primary cause of it. Even if biology were always the primary and necessary cause of psychotic experience, there would still be a role for approaches to understanding psychosis which link it to the lived experience of patients in ways which are acceptable, meaningful and helpful to them.

MYTH: Using psychodynamic principles is incompatible with a cognitive–behavioural approach

FACT: Psychodynamic and cognitive–behavioural approaches to formulation have in common the goal of trying to make sense of the person's difficulties through considering thoughts, feelings, behaviours and life contexts. Both consider past and present experiences and circumstances, content of symptoms, and devise formulations which can be tested. Formulations from both approaches can be presented in similar frameworks and although terminology is not always shared, technical psychodynamic terminology is not essential to developing a formulation. There are differences in other aspects, for example the emphasis in a psychodynamic approach on the unconscious, on interactions between patient and staff, on practitioners' countertransference and associations, and in group discussions on attention to boundaries and reflection time. Although such differences in emphasis may require consideration and compromise, there is evidence that these different theoretical approaches can be successfully combined in practice, and also used in conjunction with systemic principles (Reference DavenportDavenport 2002; Reference SummersSummers 2006).

MYTH: Using different models alongside each other is too confusing

FACT: There are examples where teams have drawn on different models (Reference DavenportDavenport 2002; Reference SummersSummers 2006) without this being perceived as a problem. Individual practitioners with skills in different approaches may regularly draw on a range of theoretical perspectives.

MYTH: A psychodynamic approach just focuses on the person's childhood and is not relevant to addressing current difficulties

FACT: A psychodynamic perspective (like many others) considers that a person's early life experiences have a significant effect in shaping their inner world and thus their later experience and difficulties. Having hypotheses about the roots of a person's difficulties can help the individual feel more accepting of themselves, and help those working with them be more able to be empathic when the going is difficult. However, the purpose and focus of a psychodynamic approach – whether in formulation or therapy – is on improving understanding of how things work in the person's mind in the present.

MYTH: Formulation should not be done without the patient collaborating

FACT: In a sense, this happens all the time, as every practitioner, even with the clear intention of working collaboratively, will form their own ideas about patients, and will – appropriately – not see fit to discuss all of these with their patients. There are some advantages to sometimes working on formulation away from the patient, for example in being able to reflect more freely (see case vignette 2) and accessing other perspectives. This is not to say, however, that this should be instead of making our best attempts to develop a shared understanding with patients and, where appropriate, their families. There is evidence that this can work well (Reference Aaltonen, Seikkula and LehtinenAaltonen 2011; Reference Seikkula, Alakareb and AaltonenaSeikkula 2011). In working directly with patients and families, a tentative approach is crucial (Reference Johnstone, Johnstone and DallasJohnstone 2006) and a higher level of skill may be needed.

Conclusions

In summary, as stated in the NICE guidance (2009), psychodynamic principles can be used to generate hypotheses that may be helpful in better understanding people with psychosis and in guiding their general clinical care. They can be used in combination with ideas based on other theoretical models. We have argued that there may be significant clinical benefits in using psychodynamic principles in formulation in everyday practice, that costs need not be prohibitive, and that the changes required are within the grasp of most NHS teams.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Psychodynamic formulations:

-

a must be verbalised and written down

-

b must be developed jointly by a team

-

c must always be discussed fully with the patient concerned

-

d can apply to organisations, teams or individuals

-

e are not used in psychoses which are predominantly neurodevelopmental in origin.

-

-

2 A psychodynamic perspective:

-

a is in conflict with recent findings on biological aspects of psychosis

-

b is incompatible with a cognitive–behavioural approach

-

c is incompatible with a cognitive analytic approach

-

d suggests that medication should be avoided

-

e considers unconscious processes.

-

-

3 When psychodynamic principles are used in team discussion of formulations:

-

a ideas derived from cognitive–behavioural therapy should not be considered

-

b participants should be encouraged to confine their comments to the agreed issue

-

c all participants should have psychodynamic training

-

d management support does not have any effect

-

e care plans may change as a result.

-

-

4 Unconscious processes in a patient's mind may be elucidated through attention to:

-

a patterns in the patient's relationships with family and friends

-

b practitioners' countertransference feelings

-

c practitioners' associations to the patient's story

-

d the content of psychotic symptoms

-

e all of the above.

-

-

5 A psychodynamic formulation can be readily used to assist:

-

a payment by results clustering

-

b DSM-IV diagnosis

-

c ICD-10 diagnosis

-

d relapse prevention

-

e monitoring of service user experience.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | d | 2 | e | 3 | e | 4 | e | 5 | d |

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Bent Rosenbaum, Judith Smith and Dr Nanda Palanichamy for thoughtful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.