Why self-help?

Both primary and secondary care practitioners often wish to offer their patients access to effective psychosocial interventions, yet the lengthy waiting-lists for specialised psychological or psychotherapeutic services create frustration among both referrers and their patients. There is therefore a need for new ways of accessing such treatments that can be delivered in most psychiatric team settings. For this to be realistic, such delivery must be possible within the time available to most practitioners (10–20 minutes for many consultant psychiatrists). One approach is to offer structured self-help materials.

What is self-help?

The term self-help has been applied in many different contexts, ranging from self-help groups to help-seeking behaviour and self-care. According to Cuijpers' (1997) description, in self-help

“the patient receives a standardised treatment method with which he can help himself without major help from the therapist. In [the approach] it is necessary that treatment is described in sufficient detail, so that the patient can work it through independently. Books in which only information about depression is given to patients and their families cannot be used.”

Although information provision is a component of self-help approaches, it is important to differentiate materials used for self-help from materials that aim only at patient education. The goals of self-help and patient education are different, and this should be borne in mind when using or producing self-help materials.

In this article, the term ‘self-help’ is used to describe materials delivering treatment in a medium-based format (such as books, audio- or videotapes or computer presentations: see Box 1) and that are used by an individual for self-treatment. This may be provided independent of (unsupported self-help) or in addition to sessions with a health care practitioner (supported self-help).

Box 1. Formats of self-help delivery

People like to learn in different ways and the various formats in which self-help materials are delivered allow them to choose the media they prefer

Audiotape used, for example, in learning a relaxation approach

Videotape especially for skills-based learning or to show, in documentary style, the impact of a problem on others who share it; videos may also show skills in practice, such as undergoing planned exposure in a supermarket

Written materials handouts, workbooks and books, in printed format or via the internet (as downloadable files that may then be printed out); this is the most-used format of self-help

Interactive computer materials questions may be asked of the user and, depending on the responses, specific information or interventions provided

Virtual-reality presentations of particular use in treating phobias, as they allow simulation of situations that are difficult to reproduce, such as flying and exposure to certain insects

Interactive touch-tone or voice-activated telephone access the patient interacts with a central computer by telephone

Is self-help effective?

Various self-help materials have been assessed and shown to be a effective. To date four meta-analyses have been completed (Reference Scogin, Bynum and StephensScogin et al, 1990; Reference Gould and ClumGould & Clum, 1993; Reference MarrsMarrs, 1995; Reference CuijpersCuijpers, 1997).

Scogin et al (1990) summarised 40 studies that used bibliotherapy (written materials/manuals) and compared self-administered with therapist-administered treatments.

Gould & Clum (1993) examined 40 self-help studies that had a control group (no treatment, waiting-list or placebo). The studies addressed clinical targets ranging from smoking to mood disorders and sexual dysfunction. Treatments included audio- and videotape and written materials/manuals. They did not include materials delivered by computer.

Marrs (1995) combined 70 studies that compared bibliotherapy with a control group or other therapist-administered treatment. Thirty studies made direct comparisons between equivalent patients treated by either self-help or a therapist. These studies included written materials, audio- and videotapes and also computer-delivered material.

Cuijpers (1997) examined in detail six studies that randomly allocated patients to bibliotherapy or a waiting-list control group. This review included computer-based treatments within the term bibliotherapy.

The key findings of these meta-analyses are that self-help approaches can be effective. The overall treatment effect sizes recorded were as follows: 0.96 for self-administered treatments compared with controls, and 1.19 for bibliotherapy with minimal therapeutic contact compared with controls (Reference Scogin, Bynum and StephensScogin et al, 1990); 0.76 at post-treatment and 0.53 at follow-up (Reference Gould and ClumGould & Clum, 1993); 0.565 and maintenance of the effect size at follow-up (Reference MarrsMarrs, 1995); 0.82 (Reference CuijpersCuijpers, 1997). (An overall effect size of 0.1–0.32 reflects a small treatment effect of the self-help approach, 0.33–0.55 a moderate effect, and 0.56–1.2 a large effect.)

Overall, self-help treatments appear to be most effective for skills-deficit training (such as assertiveness training) and the treatment of anxiety, depression and sexual dysfunction.

Additional therapist input appears to have no effect on patient outcome above what is obtained by self-help treatments alone (Reference Scogin, Bynum and StephensScogin et al, 1990; Reference Gould and ClumGould & Clum, 1993; Reference MarrsMarrs, 1995). However, anxiety treatments may be more effective when there is additional therapist contact (Reference MarrsMarrs, 1995).

The finding that more intensive input from a health care practitioner appears to add nothing flies in the face of the beliefs of many practitioners that supported self-help approaches are more likely to be effective than unsupported ones.

Overall, it is clear that some materials are effective and that self-help approaches are generally acceptable to patients – especially those who wish to take some control over their treatment. There are, however, significant problems with these meta-analyses, including an overemphasis on samples recruited via advertisement coupled with the use of very broad exclusion criteria. More recent studies have examined UK-based psychiatric samples and found acceptable take-up and clear clinical benefits from the use of self-help materials for the treatment of anxiety and depression (e.g. Whitfield et al, 2001).

What is needed is a systematic review of the use of self-help materials and such a review is currently being undertaken.

Self-help materials address a wide range of problems using the various delivery formats (Box 2), and in order to narrow the focus of this article we will consider the use of written materials developed for the treatment of depression – the so-called ‘bibliotherapy’ approach. The principles of management are, however, transferable and can be more generally applied to the use of other self-help delivery formats.

Box 2. The scope of self-help materials

Self-help approaches are largely used for mild to moderate mental health problems that have specific treatment goals (e.g. learning to relax, gaining problem-solving skills and identifying and challenging unhelpful thoughts)

The two most common disorders addressed by self-help materials are:

-

• Anxiety (worry, panic, generalised anxiety disorder)

-

• Depression

Other clinical problems for which self-help materials are available include:

-

• Alcohol/substance misuse

-

• Chronic fatigue

-

• Eating disorders

-

• Post-traumatic stress disorder

-

• Psychosis/schizophrenia

-

• Sexual and relationship problems

Skills-based materials address such issues as:

-

• Problem-solving

-

• Assertiveness training

Pros and cons of structured written self-help materials

Self-help materials are popular with the general public and self-help books are often among the top 50 best-sellers. The choice of self-help materials is rarely based on research evidence. An American survey reviewed which self-help materials were used by clinical psychologists and identified a wide range of materials, less than 10% of which had been evaluated in any form of clinical study (Reference QuackenbushQuackenbush, 1991). Self-help approaches potentially have both advantages and disadvantages.

Potential benefits

Self-help approaches can be an effective way of delivering treatment either as the main or a supportive component of treatment, which may be accessed with minimum delay.

Self-help provides a partial answer to demands to offer effective psychosocial interventions and is popular and acceptable to many patients. Furthermore, the price of written materials is low compared with specialist mental health treatment.

Self-help approaches may allow patients ready access to help that they would otherwise reject, wishing to avoid the stigma of psychiatric referral or protect their privacy. Patients may be attracted to the idea of working on their own to deal with their problems, thus avoiding the potential embarrassment of formal psychotherapy.

Patients take responsibility for self-management, working in their own time and at their own pace. This might empower them and promote collaboration. It may also enhance their sense of control over their illness.

Self-help offers the chance to reinforce or consolidate learning. Patients can return to the material whenever the need arises. They can therefore renew or update their treatment as often as they wish, and at no extra cost.

Materials can also help the person to identify early warning signs of relapse and to prepare a plan of action to deal with them.

Potential disadvantages

The finding that some self-help materials are effective does not imply that all will be.

Sometimes patients do not like the idea of using self-help approaches. They need to accept the approach as a valid treatment option.

Self-help materials should be delivered using a format, structure and content accessible to and understandable by the specific user. A certain level of education is often assumed in materials, and readability statistics are rarely completed or reported. This may be a crucial factor affecting access to and usability of materials.

Materials should not exclude users from different ethnic and minority groups. Ideally, a range of culturally specific materials should be presented, preferably with translations of the materials in different languages. Few materials have been developed for use by children or those with learning difficulties.

The offer of inappropriate self-help materials to agitated or distressed patients may exacerbate problems. Patients with severe depression may have concentration and memory problems that make the use of written self-help materials difficult. If handled poorly, such patients may misperceive the offer of self-help as a rejection and this can result in further distress.

Many self-help books guarantee that they can cure problems; this may create false expectations and any failure to deliver improvement may result in patient deterioration.

Drop-out from using the materials can be high – especially when the use of self-help is unmonitored by a health care practitioner. Drop-out is related to poor motivation and feelings of hopelessness. A wide range of drop-out rates for bibliotherapy have been estimated: from about 7% (Reference CuijpersCuijpers, 1997) up to 50% (Reference Glasgow and RosenGlasgow & Rosen, 1978).

CBT and self-help

Has a patient you are working with ever said to you “What you said last time really made a great difference” – yet you cannot remember quite what you said? This common experience indicates that asking the right question or providing the right information can make a real difference to how the patient feels. The concept of asking sequences of effective questions and providing appropriate information is the basis of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) – a psychotherapy that has a proven effectiveness in the treatment of depression and anxiety (Reference AndrewsAndrews, 1996). This use of effective questioning and information provision can be offered on an individual basis, to groups or in self-help formats. However it is delivered, the aim is to help patients identify and then change unhelpful and extreme ways of seeing things and also unhelpful behaviours that might be adding to their problems. Interestingly, most studies evaluating self-help have used a CBT format. CBT has several other advantages as a model for use in self-help treatment. It is an educational form of psychotherapy, has a clear underlying structure and theoretical model and focuses clearly on current problems. Furthermore, it adopts a collaborative stance with patients that encourages them to work on changing how they feel by completing various specific tasks. It is noteworthy that, in reviews of self-help, CBT materials are among the group of self-help materials with the strongest evidence for effectiveness.

Box 3 shows examples of CBT self-help materials used within psychiatry.

Box 3. Some structured written self-help materials that use a cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) approach

Feeling Good ( Reference Burns Burns, 1998 ) One of the first CBT self-help books. Developed in the USA. Details at www.feelinggood.com

Managing Anxiety and Depression ( Reference Holdsworth and Paxton Holdsworth & Paxton, 1999 ) A short booklet, recently revised. UK developed by the Mental Health Foundation. Aimed at milder levels of distress rather than moderate or severe depression. Details at www.mentalhealth.org.uk

Mind over Mood: Change How You Feel by Changing the Way You Think ( Reference Greenberger and Padesky Greenberger & Padesky, 1995 ) Aimed at anxiety and depression, this US-developed book has been very successful. Allows photocopying of worksheets for use with patients. Details at www.padesky.com

Overcoming Depression: A Five Areas Approach ( Reference Williams Williams, 2001 ) A series of 10 workbooks, six of which can be downloaded free of charge from www.calipso.co.uk . License provided for unlimited photocopying for use with patients and in teaching. The Calipso site also includes details of accompanying training support materials

Introducing the idea of using self-help materials

If, after the clinical assessment, the health care practitioner thinks that self-help approaches may be beneficial to the patient, the role of self-help materials as part of the treatment plan can be discussed and the patient's attitudes to the use of such materials evaluated. Useful questions to explore attitudes towards the use of such materials include:

-

• “What is your initial reaction to the idea of using self-help?”

-

• “Have you used any self-help materials before? Were they useful?”

-

• “Has anyone you know used this approach?”

Doubts and concerns about the use of self-help materials must be addressed. It is important to emphasise that this is only one possible part of the whole treatment. Sometimes a person may choose not to take up the offer of self-help materials, or it may be more appropriate to consider their use at a later time – for example after a course of antidepressant medication, which may improve concentration, energy and motivation to levels at which the use of self-help materials may be more realistic.

Using self-help approaches with patients

If the patient is interested in using a self-help approach, the discussion should cover the materials available, the patients' preferred format for such materials and the part that the materials may play in treatment. A single sheet can be produced that summarises the range and format of materials available within a particular clinical service.

The following would usually rule out the use of self-help approaches:

-

• the patient is not interested in using self-help

-

• severe/major depression, with very poor concentration and energy levels that make using the materials difficult

-

• visual, hearing or reading difficulties that prevent effective use of certain delivery formats.

Self-help materials are most effective when the target problem areas are clearly stated. It is useful to have materials in a range of delivery formats, such as audio, written, CD–ROM or internet, so that a format that the patient is happy to use may be chosen.

With supported self-help the materials are expected do at least some of the work of treatment and to supplement the work done individually with the patient. The materials may therefore reduce the length of each session with the practitioner, or reduce the total number of sessions required. This approach is sometimes referred to as reduced or minimal therapist contact. Regular review sessions are offered so that progress is monitored. The cycle of using self-help materials at home and then discussing with the therapist which aspects were clear/helpful and which more difficult/unhelpful can provide a structure to the treatment. This process is summarised in Fig. 1.

How often should a progress review occur?

Regular review or monitoring sessions (perhaps fortnightly) allow patients to discuss with the practitioner materials used between sessions. A 7- or 8-minute review will allow brief discussion of areas that are going well, identify problem areas and let the health care worker hand over the next set of materials to be worked on at home. In some practitioner groups members of multi-disciplinary mental health teams may have more time available for the review sessions. This may be used for more detailed discussion of specific components of the content (for example, a completed thought-challenge worksheet could be focused upon).

Improving learning and overcoming difficulties in using self-help materials

Box 4 shows advice that may be given to help patients to gain maximum benefit from self-help materials.

“I didn't have time”

Breaking old habits and starting new ones takes practice. Encourage patients to set aside time to change: explain that this is their right. It may be that they think that they have too many external pressures (e.g. a partner, children or job) to look after their own needs. Getting better should be a priority, and it is important for patients and for those around them that they have time to allow themselves to achieve this.

“I didn't understand what I had to do”

If patients feel stuck, encourage them to try to re-read the materials. If they are still confused, encourage them to talk to you about particular difficulties they have with understanding what to do. If the patients' symptoms of depression are interfering with their use of the materials, an antidepressant might help. If problems continue it may be that different self-help materials are more appropriate, or that a change to other treatment options is indicated.

“I tried but it didn't seem to make any difference”

Change takes time. A person may have been depressed for quite some time and it will take time to begin to change. The first steps towards change are often the most difficult. Try to encourage patients to stick at it. Using self-help approaches involves learning new knowledge and gaining new skills in overcoming problems. Reassure patients that although this may be a slow process, they can change, one step at a time.

Two useful interventions when patients are “feeling stuck”

Remember how difficult it can be to learn

Sometimes it is easy to forget how difficult it was to learn new information or skills that we now take for granted. Ask patients to think about some of the skills they have learned over the years. For example, if they can drive, ask them to think back to their first driving lesson. It is unlikely they were very good that first time, yet with practice they developed the new knowledge and skills needed. They can learn the skills to overcome their current problems in the same way. It may seem difficult at first but they need to keep practising what they learn.

“What advice would you give to a friend who said ‘I'll never learn anything using these materials’?”

Often people can give far better advice to someone else than they give to themselves. Use this to illustrate this ‘one rule for you, another for others’ tendency and get patients to follow their own good advice.

Box 4. Improving the learning process (after Williams, 2001)

Patients may be given the following advice on improving their use of materials

Stop, think and reflect

Evidence suggests that people who interact with written worksheets and complete the homework tasks suggested in the materials do better than those who do not. This is best done by answering all the questions that are asked

Take notes

Jot down notes in the margins or at the back of the materials to help you remember information that has been helpful. Review these notes each week

Review to consolidate

Once each chapter or workbook has been completed, put it aside and then re-read it a few days later. It may be that different parts of the text become clearer or seem more relevant on second reading

Including self-help treatments in your service

Self-help materials can be used in different parts of a clinical service. For example, self-help may be offered to patients on waiting-lists, supported or unsupported by limited access to a health care practitioner (see, e.g., Whitfield et al, 2001). It may also be used to support individual work and group treatments with a health care practitioner (such as a psychiatrist, community psychiatric nurse, occupational therapist or social worker).

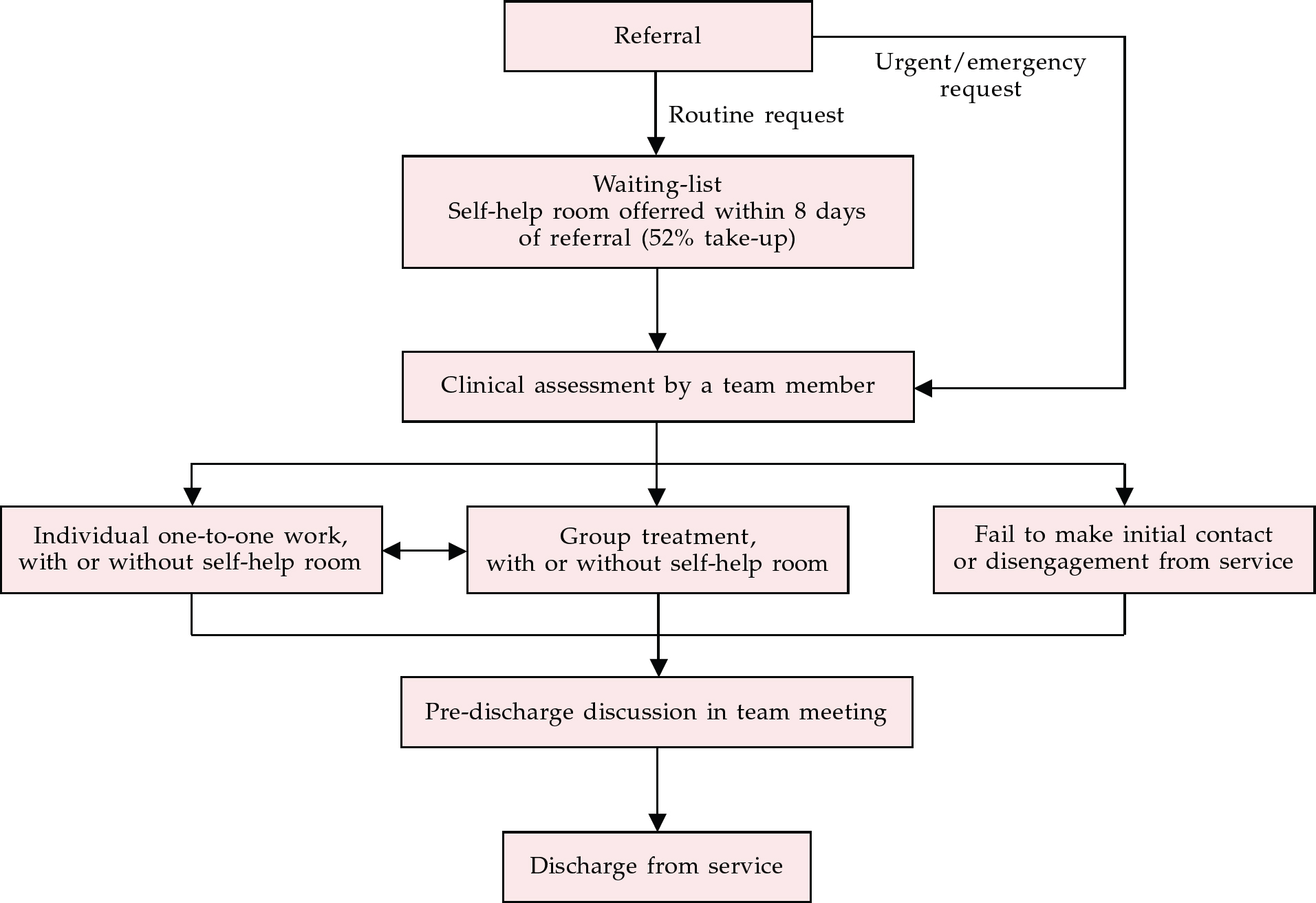

One way that self-help delivery can be encouraged within a clinical service is to introduce a focus for it. One such approach has been developed at Malham House Day Hospital in Leeds. Here, a specific self-help room was designated within an adult acute day hospital setting. This provides a central resource for use by day hospital staff, out-patients (including waiting-list patients) and patients being seen by members of the multi-disciplinary mental health team. The system is illustrated in Fig. 2. Self-help approaches can be integrated to support other treatments offered within the different clinical settings (e.g. at the day hospital or resource centre, and in both in-patient and out-patient settings). This has the advantage to the team and the patient of allowing a consistent management plan to be offered across these different settings.

Setting up a self-help room

The team setting up a self-help room must decide:

-

• the materials to offer in it

how to support it (e.g. consider the cost and practicalities of providing original copies of materials and photocopies of worksheets)

-

• how to provide an atmosphere that encourages both the patient and the clinical service to use self-help approaches.

Perhaps the easiest way of delivering self-help is to offer copies of a book or photocopies of materials within the room. Some units ask for a returnable deposit on books borrowed.

In the Malham House self-help room it was decided that only two sets of materials would be used, both in written format – Mind over Mood (Reference Greenberger and PadeskyGreenberger & Padesky, 1995) and Overcoming Depression: A Five Areas Approach (Reference WilliamsWilliams, 2001). This ensures that all staff are aware of the material on offer and can become familiar with its content. Plants, rugs and pictures on the walls create a relaxing atmosphere. A desk, pens and paper maintain a central focus on the materials. The room is used by only one person at a time, to ensure privacy, and a booking system allows users sessions of up to 1 hour. Patients are encouraged to use the room once or twice a week, and to keep all their completed workbooks and worksheets, to create their own personalised treatment pack. The room is kept neat and tidy, and one of the secretaries ensures that pens, paper and photocopied workbooks/worksheets are available when the room is open.

To ensure effective staff use of the selected self-help materials, weekly staff training sessions were offered before the room was opened. Everyone in the team was expected to read each component of the materials a week ahead of each session, and then one or two team members presented the key contents to the rest of the team. This allowed discussion of how the materials may be best used, aided familiarity with content (crucial for effective use) and allowed role-play practice of how to respond to difficulties in treatment.

Overcoming Depression: A Five Areas Approach was originally commissioned by Calderdale and Kirklees Health Authority and has been widely tested by a range of health care practitioners, including psychiatric nurses, clinical psychologists, psychiatrists and behavioural nurse therapists based in community and day hospitals, and general practitioners and practice nurses. The development phase also included extensive testing with patients to ensure clarity of content. It comprises 10 structured CBT workbooks that address common problems experienced in depression. Feedback from users and professionals has led to changes and improvements in the content over the past 2 years. Readability statistics show that all of the material has a reading age between 11 and 14 years (most workbooks have a reading age of 11–12 years). The materials are aimed at patients with mild to moderate depression, including those with biological symptoms of depression that are not at a level where concentration or memory problems preclude the use of written materials. Training is offered to health care practitioners to help familiarise them with the content of the materials and local ‘experts’ have been trained in the approach. Most of the materials can be downloaded free of charge from www.calipso.co.uk.

A survey at Malham House examining the attitudes of staff and patients towards the use of self-help approaches within the service showed strong satisfaction with the room and the self-help approach. An outcome study of the use of the room has shown a take-up of 52%, even among unsupported inner-city individuals on the general adult waiting-list (Reference Whitfield, Williams and ShapiroWhitfield et al, 2001).

Summary

Self-help approaches can be a useful extra tool in patient treatment. They allow patients ready access to structured and effective psychosocial interventions such as CBT. Materials may be used either supported or unsupported by a health care practitioner, and should have a structure and content that maximises usability. Self-help may be an integral part of service delivery within general psychiatric services. Training in the use of self-help is important, and all workers should be aware of the contents of the materials on offer.

Multiple choice questions

-

1. The following are desirable in self-help treatments:

-

a the patient should be medication-free

-

b the materials should encourage the user to stop, think and reflect

-

c materials should focus on current problems

-

d users should be discouraged from practising what they learn.

-

-

2. The following are desirable features to look for when choosing a self-help package:

-

a the use of interactive worksheets

-

b a licence allowing photocopying for clinical teaching and practice

-

c known readability level of the materials

-

d font size less than 11.

-

-

3. The choice of self-help material:

-

a is normally best left to the patient

-

b requires certification under national guidelines

-

c should be guided by an evidence base

-

d depends on the reading age and ethnic background of the patient.

-

-

4. Self-help rooms:

-

a should be sited in a quiet place such as a library

-

b can replace the need for any discussion of psychosocial issues

-

c may support individual and group-based work

-

d require frequent monitoring to ensure that sufficient materials are available.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | T | a | F | a | F |

| b | T | b | T | b | F | b | F |

| c | T | c | T | c | T | c | T |

| d | F | d | F | d | T | d | T |

Fig. 1. Using self-help materials

Fig. 2 Self-help as a part of the whole service delivery at Malham House Day Hospital in Leeds

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.