It is impossible to ignore the focus in the past few years on clinical leadership both in the professional literature and in government papers, most notably the landmark Darzi Report, also known as the NHS Next Stage Review (Reference DarziDarzi 2008). Lord Darzi's report set the scene in terms of highlighting the importance of involving clinicians in leadership roles, which in subsequent years has been developed further as a concept by professional institutions across the UK. Of note, the review also emphasised the delivery of healthcare by teams across patient pathways as key to improving quality of care (Reference DarziDarzi 2008; Reference Stanton, Chapman, Stanton, Lemer and MountfordStanton 2010). Recent Advances articles have also focused on the need for psychiatrists to acquire excellent leadership skills (Reference Garg, van Niekerk and CampbellGarg 2011; Reference Brown and BrittlebankBrown, 2013).

The development of clinical leadership skills has been formally recognised as a necessary part of training for doctors and the relevant competencies have been outlined in the Medical Leadership Competency Framework (MLCF), introduced by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges and the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement in 2008 (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement 2010). The MLCF is now embedded in the different specialty training postgraduate curricula, including psychiatry (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2010a). ‘Working with others’ is one of the key MLCF domains and contains four key competencies for working in teams (Box 1).

BOX 1 Key competencies for working in teams

Doctors should:

-

• have a clear sense of their role, responsibilities and purpose within the team

-

• adopt a team approach, acknowledging and appreciating efforts, contributions and compromises

-

• recognise the common purpose of the team and respect team decisions

-

• be willing to lead a team, involving the right people at the right time

Leadership and teamwork in psychiatry

Effective multidisciplinary teams are associated with high-quality patient care (World Health Organization 2009). As a general rule, mental healthcare is very much organised around teams, be they assertive outreach teams, home treatment teams, in-patient teams or other community mental health teams. Psychiatrists tend to work within comparatively flattened hierarchies relative to other clinical specialties, which may be more conducive to teamworking. The familiarity of psychiatrists with working in this way, their advanced communication skills and an understanding of group dynamics should all mean that psychiatrists have key skills for working within and leading teams.

However, psychiatrists over the past decade have been working in a changing environment. New Ways of Working, a government-led initiative, has had profound effects on mental health service design and delivery. It aimed to move mental healthcare delivery towards a more competency-based rather than professionally based model. This has led to questioning of the role of psychiatrists as leaders of the multidisciplinary team, with a move towards a more distributed leadership model (Department of Health 2007; Reference Craddock, Antebi and AttenburrowCraddock 2008). The Royal College of Psychiatrists has its own focus on this matter, publishing a paper on the leadership role of the consultant psychiatrist (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2010b). This describes consultants as ‘uniquely positioned to lead a team in such a way that practice and outcomes for patients are good and are continuously improving’. It also identifies two important aspects of leadership by consultant psychiatrists: ‘clinical decision-making in multidisciplinary contexts’ and ‘managing dynamics in the team setting’. Bearing this context in mind, this article will focus on the psychiatrist's role as a leader of teams, considering how teams function and how they can work effectively to provide high-quality patient care.

What are teams?

Teams can be considered as a form of a group. However, there are important differences. Groups may be defined as a number of people who interact with one another and who are psychologically aware of one another (Reference MullinsMullins 2005). Teams differ in that leadership becomes a shared activity, accountability may be collective, there is a common purpose of mission and effectiveness is measured by the group's collective outcomes (Reference Greenberg and BaronGreenberg 2003). One definition of a team is ‘a group where members have complementary skills

Psychiatrists within the team

Psychiatrists are likely to work in a number of identifiable teams, the most immediately apparent being their multidisciplinary clinical team. However, there are a number of other groups that they may be either consciously or unconsciously a part of, such as managerial teams (for clinical or project leads), research teams, educational teams, junior doctor peer groups and so on. Working as part of a team can be one of the most rewarding experiences of being a doctor, but teamworking is not without its difficulties. To either lead a team effectively or be a productive member of a team, it is useful to have an understanding of how groups and teams form and evolve over time.

Reacting to change

One difficulty is that the membership of most clinical teams is not static: there are often frequent changes, such as when new doctors join a particular clinical team as part of their training rotations or new individuals become involved in a project or management team. This can result in shifting dynamics and, arguably, there is a need for new members to integrate as quickly as possible for the group to remain effective. Healthcare teams in particular can be fluid and lack clear boundaries; this makes them complex and more difficult to evaluate and understand (Reference Stanton, Chapman, Stanton, Lemer and MountfordStanton 2010).

The life-cycle of a team

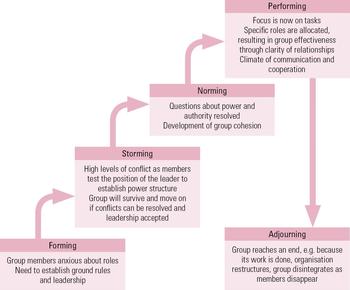

Reference TuckmanTuckman (1965) described probably the most popular model for how groups and teams form and evolve. He identified four key stages, with a fifth added later (Fig. 1). In this model, the needs of individuals may dominate at the beginning of the process; if personal and interpersonal issues are unresolved then focusing on the tasks may remain relatively unimportant to group members (Reference GuirdhamGuirdham 2002). As the name implies, performing is the stage in which the work gets done and the group is most likely to fulfil its responsibilities and achieve its goals; ideally, teams will reach this stage as quickly as possible and remain in it for as long as is necessary. Progress through the stages may be hindered by too much instability within the group (such as frequent changes in membership because people leave and join the team) and effort should be made to ensure that new members are welcomed and brought up to speed rapidly, as well as ensuring that vital knowledge is not lost if members leave the team.

FIG 1 Tuckman's five-stage model (adapted from Reference MullinsMullins 2005). and are committed to a common purpose or set of performance goals for which they hold themselves accountable' (Reference Greenberg and BaronGreenberg 2003).

Group dynamics

Individuals' reasons for joining the group

Individuals can have a profound effect on groups and groups can profoundly affect the individual (Reference Stanton, Chapman, Stanton, Lemer and MountfordStanton 2010). To understand teams better, it is helpful to understand why people join them in the first place. Reference Greenberg and BaronGreenberg & Baron (2003) outlined four main reasons that can be identified in individuals:

-

• to satisfy mutual interest

-

• to achieve security

-

• to fulfil social needs

-

• to fulfil a need for self-esteem.

Dealing with anxiety

No discussion of group dynamics and function would be complete without mention of Wilfred Bion's pioneering work on group relations (Reference Bion1961). He described three basic assumption states that may occur within a group when it is faced with uncontrollable anxiety and showed that these can co-exist within a so-called ‘sophisticated work group’ that is dealing with a primary task. The three states are:

-

• pairing – group development is arrested by a hope of being rescued by two members who will pair and somehow create a solution;

-

• fight/flight – the group acts as if its main task is to fight or flee from a common enemy; this enemy might be either inside or outside the group; and

-

• dependency – the group seeks a leader who will relieve them of their anxiety; once found, this leader is expected to be able to solve all problems and, if they do not, they will be attacked and a replacement will be sought.

The group may switch between these basic states or may become stuck in one state. Identification of basic assumption states within a team can provide explanations for behaviour that may otherwise be difficult to understand and offer a way of addressing underperformance.

Conformity within groups

Other problems within teams may arise as a result of the power of conformity in groups. The famous Asch experiments of the 1950s demonstrated the powerful effect of conformity on group decision-making (Reference Stanton, Chapman, Stanton, Lemer and MountfordStanton 2010). Participants tended to change their opinion to reflect that of other group members, but only one dissenting voice in the group dramatically reduced this tendency.

Groupthink

A related concept is groupthink, which has been defined as a mode of thinking that people engage in when they are deeply involved in a cohesive group; members' strivings for unanimity override their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action (Reference JanisJanis 1972). Groupthink can particularly occur in situations where, for example, teams face moral dilemmas or highly stressful external threats – factors that are common in mental healthcare. Groupthink will result in faulty team decision-making because all options are not properly considered and evaluated. A clinical example where consideration of this phenomenon is particularly crucial is multidisciplinary team decisions about risk assessment and management, because a strong and authoritative opinion in a cohesive team may lead to a potentially more risky care plan than may have resulted from a thorough consideration and discussion of all available options. In addition, groups are likely to feel more able to take bigger risks than individuals in isolation. Various strategies can be adopted to avoid groupthink, including team members taking it in turns to play devil's advocate and discussing the team's decisions with trusted external people or experts.

The Six Thinking Hats

A popular method for promoting fuller input from more team members and ensuring that decisions are considered from all important perspectives is the Six Thinking Hats technique (Reference De BonoDe Bono 1985; Box 2). When used in team meetings it has the benefit of preventing the confrontations that can occur when people with different thinking styles consider the same problem. In addition, it can be helpful when ensuring that important decisions, such as the clinical risk assessment and management example in ‘Groupthink’ above, are considered thoroughly and from all angles. The six hats represent six different modes of thinking and are directions in which to think rather than labels for thinking. When considering a decision, one of the metaphorical hats should be put on to indicate the type of thinking being used at the time. When this method is used in a group, everybody should wear the same hat at the same time to avoid categorising individuals on the basis of their behaviour or personality traits. A key theoretical reason to use the Six Thinking Hats technique is to separate ego from performance, allowing a full exploration of a decision.

BOX 2 The Six Thinking Hats technique

Blue hat – controls the thinking process (e.g. ‘We need to focus on white-hat thinking now’). This hat would be worn by the chair of the meeting, who may need to stop team members criticising others' viewpoints or switching styles before it is decided that the team should switch

Red hat – looks at problems using intuition, the emotions and gut feelings

White hat – focuses the group on the available data, facts and figures

Green hat – creativity and alternatives

Black hat – the pessimistic viewpoint, logical and cautious

Yellow hat – the optimistic viewpoint, seeing the benefits or values in an option

(After Reference De BonoDe Bono 1985)

Team roles

Individuals may adopt different roles within teams depending on their personality, professional backgrounds and skill set. In certain situations doctors may be clearly leading a team, but at other times may need to take on a different role. Diversity of roles within teams is thought to improve performance (Reference GuirdhamGuirdham 2002) and much work has been done to describe the various roles that need to be fulfilled in an effective team. One of the best known and most widely used descriptions of team roles is that developed by Reference BelbinBelbin (2006). He argued that for teams to function optimally, each of the nine roles outlined in Box 3 needs to be fulfilled and that if too many team members have similar roles this can lead to friction and reduced effectiveness. As well as developing detailed descriptions of these individual roles, Belbin also created a profiling questionnaire that enables individuals to identify which roles they are most likely to adopt (www.belbin.com).

BOX 3 Belbin's team roles

Coordinator

-

• Needed to focus on the team's objectives, draw out team members and delegate work appropriately

-

• Can summarise the view of the group

-

• Might over-delegate, leaving themselves little work to do

Shaper

-

• Challenges the team to improve

-

• Provides the necessary drive to ensure that the team keeps moving

-

• Happy to challenge and be challenged

-

• Can risk becoming aggressive and bad-humoured in their attempts to get things done

Plant

-

• Presents new ideas and very creative

-

• Good at solving problems in unconventional ways

-

• Pays less attention to detail

-

• May be unorthodox or forgetful

Resource Investigator

-

• Has strong contacts and networks

-

• Explores outside opportunities

-

• Can provide inside knowledge on the opposition

-

• May forget to follow up on a lead

Implementer

-

• Can plan a practical, workable strategy and carry it out as efficiently as possible

-

• Has practical common sense and realism

-

• Might be slow to relinquish their plans in favour of positive changes

Teamworker

-

• Cooperative and supportive, socially orientated

-

• Helps the team to gel, uses their versatility to identify the work required and complete it on behalf of the team

-

• Might become indecisive when unpopular decisions need to be made

Completer Finisher

-

• Ensures thorough, timely completion

-

• Perfectionist and conscientious, protects team from error

-

• Can have problems delegating

Monitor Evaluator

-

• Ability to analyse problems and evaluate ideas

-

• Provides a logical eye

-

• Makes impartial judgements where required

-

• Can be overly critical and slow moving

Specialist

-

• Single minded and dedicated

-

• Provides knowledge and skill in a particular field of expertise

-

• May have a tendency to focus narrowly on their own subject of choice

(Adapted from Reference BelbinBelbin 2006, with permission of Belbin Associates)

Arguably, the value of being able to recognise these different roles lies in spotting where imbalances may lie within a team; a high degree of self-awareness may allow a team member to consciously take on and cultivate one of Belbin's roles to optimise teamworking. Developing a personal awareness of which role you tend to be most comfortable with taking on, as well as an understanding of the other roles and their importance, will allow you to practise taking on more unfamiliar roles. Then, when faced with a situation of suboptimal team functioning (e.g. lack of a completer–finisher for a specific task) you can aim to consciously take on the missing role.

Team leadership

Key dimensions of effective clinical teams have been identified as clarity of leadership, roles, processes and objectives (Reference Markiewicz, West, Swanwick and McKimmMarkiewicz 2011). So far, we have discussed the different types of roles within teams and it would seem fairly obvious that clear objectives will be necessary for groups to enter Tuckman's ‘performing’ stage, as described earlier. So, what makes a good team leader?

There are many different types of leader and a full discussion of these is beyond the scope of this article. However, understanding one's own strengths and weaknesses is widely acknowledged as a key component of becoming an effective leader, as well as a team player. The first domain of the MLCF is the development of self-awareness; this cannot be overemphasised in terms of its importance when considering how doctors function within and lead teams. Exercises such as 360-degree appraisal (which trainees will know by the term mini-PAT – the mini Peer Assessment Tool), when conducted properly with the inclusion of constructive feedback, can be extremely useful in terms of developing greater personal awareness and understanding the effect of one's behaviour on others within the multidisciplinary team.

Some leadership programmes and courses include development of self-awareness by various other means, including the completion of personality inventories such as the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI; www.myersbriggs.org). The MBTI groups people into 1 of 16 types based on four dimensions:

-

• extraversion v. intraversion (E v. I)

-

• sensing v. intuition (S v. N)

-

• thinking v. feeling (T v. F)

-

• judgement v. perception (J v. P).

The result of the MBTI is expressed as a four-letter type, e.g. ENFP, ISTJ, ESTJ, INTP. We would strongly recommend finding out your Myers–Briggs type (questionnaire available at www.humanmetrics.com/cgi-win/JTypes2.asp) and reflecting on this with your supervisor, mentor or peer group. It is important to understand that no personality ‘type’ makes a perfect leader but doing the MBTI and other personality inventories can raise awareness of one's own potential weaknesses, which can then be counterbalanced by strengths in other members of the team.

Styles of leadership

Many different styles of leadership have been identified and described in the literature. One of the earliest and most enduring descriptions of leadership in a group setting is that of Reference Lewin, Llipit and WhiteLewin and colleagues (1939), who as well as coining the phrase ‘group dynamics’ studied how groups of children responded to different leadership styles. These three main styles of leadership (autocratic, democratic and laissez-faire, see Box 4) have since been criticised as being overly simplistic. However, they still hold relevance, with democratic leadership being recognised as the most effective style for most teams and one to which doctors should aspire (Reference Stanton, Chapman, Stanton, Lemer and MountfordStanton 2010).

BOX 4 Styles of leadership

Autocratic

-

• Clear expectations for when and how things should be done

-

• Decisions made independently with little input from the group

-

• Can be controlling, bossy and dictatorial

Democratic

-

• Responsibility for decisions is spread throughout the team

-

• Team members are actively engaged

-

• Leaders offer guidance but encourage active participation of group members

Laissez-faire

-

• Little or no guidance given to the group

-

• Decision-making left to the group

-

• Group members become less productive and less cooperative

(Adapted from Reference Stanton, Chapman, Stanton, Lemer and MountfordStanton & Chapman 2010, with permission of Mark Allen Healthcare Ltd)

Other styles of leadership have been described in more recent years and two of the most influential models are the transactional and, more recently, the transformative leadership models (Mullins 2010). The transactional model of leadership is supported by power and influence theories. It assumes that work is done only because rewards are given and so the focus is on designing task and reward systems. This model is commonly used in the business setting to get day-to-day work done. The transformational model of leadership is more inspiring and describes a leadership style that inspires trust. It centres on the leader acting as a role model and communicating a clear vision that motivates team members towards achieving team goals while encouraging and supporting them.

It can be argued that different leadership styles are best suited to different situations. For example, in an emergency an autocratic leadership style may be both necessary and life-saving. Small groups made up of extremely capable and self-motivated people may be best managed with a laissez-faire style of leadership. Groups that need motivating towards achieving difficult tasks may need a more transformational model of leadership, whereas getting day-to-day work done may be best achieved with a transactional leadership style. One of the skills of a great team leader is a flexibility of leadership style and knowledge of when to adopt which style (Reference Howell and CostleyHowell 2001).

Accountability of team leaders and distributed leadership

More recent discourse on leadership, particularly within the public sector, has emphasised the concept of more distributed leadership within teams (Reference BoldenBolden 2011) and this can often be a feature of multidisciplinary teams. This can lead to accountability and governance becoming a particular issue: it is widely believed that ultimate responsibility for clinical decision-making still rests with the consultant psychiatrist, but as a consequence of changes in work patterns and current methods of service delivery, they may see only a small number of all the patients referred to the team and are taking on more of a supervisory role (Reference Craddock, Antebi and AttenburrowCraddock 2008). In this vein, the General Medical Council has issued supplementary guidance in conjunction with the Department of Health and the Royal College of Psychiatrists. It particularly highlights the issues of supervision of other professionals, delegation of responsibility and clarity of lines of accountability (General Medical Council 2005). The guidance clearly states that doctors are not responsible for the actions of other clinicians but they are responsible for ensuring that any juniors under their supervision receive adequate support.

Overcoming barriers to effective teamworking

Teamworking can be difficult and there are many barriers to effective teamworking within healthcare organisations (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement 2007). Conflict at the group level may arise owing to differences in group values, goals, resource issues and the bases of power (Reference MullinsMullins 2005). Other issues may be specific to allegiance to professional ‘tribes’, with the possibility of professional groups trying to gain dominance over one another in an multi-disciplinary team setting; professions also often have their own language. This, in addition to high workloads and competing demands, make negotiation, conflict management and delegation vital skills for any doctor in a team leadership role.

Negotiation and managing conflict

Conflict may arise between teams or within teams themselves. It can be a source of considerable stress and limit the effectiveness of the team. However, good conflict management can result in effective resolution of issues that have been blocking the performance of the team, the development of new ideas to move forward and ultimately better performance of the team. Whole books have been written on the management of conflict and a full discussion is beyond the scope of this article; however, two useful models shall be described. Reference Fisher and UryFisher & Ury (1983) in a seminal work described four points of principled negotiation that may be used when addressing conflict. A brief summary is given in Box 5.

BOX 5 Four points of principled negotiation

Separating the people from the problem

People tend to become personally involved in situations of conflict, and this must be addressed if relationships are to be maintained

Focus on interests, not positions

Positions have been decided in advance, so a focus on positions will mean that one party will always lose and come away unhappy; interests are what cause people to take up positions and so are more amenable to negotiation

Generate a variety of possibilities before deciding what to do

Focus on shared interests, in order to avoid a win–lose mentality

Base the result on objective standards

If the parties' interests are directly opposed, they should apply objective criteria to resolve their differences

Another useful model for managing conflict was developed by Reference Rahim and BomonaRahim (1979; Reference Rahim2002), who described five styles of managing conflict and their appropriateness in any given situation, as briefly summarised below.

Integrating

Integrating is an approach for complex issues that cannot be addressed by one party, providing that time is available to solve the problem and resources to help solve the problem are not all owned by one party. It is not a suitable style for simple problems or those that require immediate decisions.

Obliging

Obliging is an approach for issues in which you as an individual may be wrong, where the issue matters more to the other party and it is important to preserve the relationship. It is not suitable when the other party is wrong or behaving unethically.

Compromising

A compromising style is for when consensus cannot be reached, a solution is needed and parties are equally powerful. It is not suitable when one party is more powerful or the problem requires a complex problem-solving approach (i.e. integrating approach).

Dominating

A dominating approach can be used when the issue is trivial and requires a speedy decision; it is not suitable if the issue is not important to you and others possess the competence to deal with it.

Avoiding

Avoiding can be used when the issues are not that important to you and are likely to have a dysfunctional effect on relationships or when a cooling-off period is needed. It is not suitable when you have a responsibility to make a decision or prompt action is needed.

Delegation

One of the key skills of managing and leading a successful team, as well as one's own workload, is that of delegation. However, delegating successfully can be a difficult skill to master. Covey's stewardship model (Reference CoveyCovey 2004) may be viewed as being most appropriate for the multidisciplinary team setting. Rather than dictating to people what to do and how to do it, stewardship delegation focuses on results instead of methods. It takes time and patience and depends on trust, but has greater benefits. People may need training to acquire the competence to rise to the level of trust required for this model. It requires a clear, up-front mutual understanding of and commitment to expectations in five areas: desired results, guidelines, resources, accountability and consequences (Box 6). Clarity in these five areas will allow effective and efficient delegation.

BOX 6 The five areas of stewardship delegation

Desired results

These, together with the deadline for achieving them, are visualised and described by the person to whom the task is delegated

Guidelines

Parameters within which the person delegated to must operate are identified, as are problems that may arise; responsibility for results remains with the person to whom it has been delegated

Resources

Resources needed to achieve the desired results are identified

Accountability

Standards of performance are set, which will be used to evaluate results, as well as specific times when reporting and evaluation will occur

Consequences

What will happen as a result of the evaluation; any results or penalties are specified

Conclusions

The importance of teamworking is becoming ever more prominent in the health service environment and doctors are likely to find themselves taking on a variety of roles within multidisciplinary teams, including that of leader. An understanding of how teams function, as well as potential barriers to teamworking, will be an essential part of a doctor's knowledge base. This knowledge should be used as a basis for developing the many skills required for successful group membership and leadership. Box 7 lists useful resources for more information on this topic. However, it should be noted that the best way to develop these skills is through practical experience while seeking open and honest feedback.

BOX 7 Useful resources

Faculty of Medical Leadership and Management

NHS Leadership Academy

Mind Tools

Belbin Team Roles

The Myers & Briggs Foundation

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 The following is an adequate summary of Tuckman's group model:

-

a forming, norming, storming, adjourning

-

b forming, storming, performing, norming

-

c forming, storming, norming, performing, adjourning

-

d forming, performing, storming, adjourning

-

e storming, forming, norming, performing, adjourning.

-

-

2 The following is not an identified leadership style:

-

a democratic

-

b transactional

-

c transformation

-

d projective

-

e laissez-faire.

-

-

3 With regard to Belbin's team roles, the following is incorrect:

-

a Belbin described nine roles that may be present within a team

-

b the company worker role is also known as the implementer role

-

c the resource investigator may find it difficult to maintain enthusiasm for a task

-

d the plant is a predominately creative role

-

e team members cannot take on more than one role within a team.

-

-

4 Regarding the four points of principled negotiation, it is incorrect to say that they:

-

a are a model for managing conflict

-

b were originally described by Rahim

-

c include separating the people from the problem

-

d were originally described by Fisher & Ury

-

e include focusing on interests not positions.

-

-

5 The following is not one of Rahim's conflict-management styles:

-

a obliging

-

b avoiding

-

c compromising

-

d dominating

-

e delegating.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | c | 2 | d | 3 | e | 4 | b | 5 | e |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.