The National Service Framework for Mental Health in England (Department of Health 1999) listed reducing suicide among its seven standards for mental health services. This made it clear that clinical staff were expected to be competent in the assessment of suicide risk and that local health economies had a responsibility to carry out a ‘suicide audit’ to learn lessons and improve the quality of services provided. Choose Life, Scotland's strategy for preventing suicide (Scottish Executive 2002), also requires training staff in risk assessment. Suicide prevention remains one of four areas of focus in the draft mental health strategy for Scotland 2011–2015 (Scottish Executive 2011), which is currently out for consultation. Crucially, these documents highlight that individual clinicians, the organisations in which they work and service users require safe methods of working together to provide effective strategies to reduce clinical risk.

Standardising procedures

Achieving effective operation in complex systems such as this is a key challenge for healthcare organisations, and a number of high-profile initiatives have attempted to address such areas. One aim of the 5 Million Lives project in the USA (www.ihi.org/ihi/programs/campaign), led by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, was to prevent 5 incidents of medical harm over 2 years. It sought to do this through encouraging healthcare providers to adopt standardised procedures. The processes chosen were those that tackled clinical circumstances associated with high morbidity and mortality, such as pressure ulcers or harm from medication use, and often focused on prevention.

Acknowledging the harms caused by service provision is a vital first step when considering how to reduce them. A number of forces, including threats of disciplinary action and litigation, tend to militate against healthcare workers reporting such events. In response, healthcare systems have made some event-reporting mandatory (for example, suicide and wrong-site surgery) and have also developed techniques of audit for harm using random selection of case notes and use of a global trigger tool (Reference Griffin and ResarGriffin 2009). This technique is well established in the acute hospital sector but only in early pilot use in a few mental health organisations. Robust implementation can gradually build a picture of where harm is occurring in an organisation and direct action to areas that require attention to reduce risk of harm.

The aspiration to standardise key aspects of clinical care and the recognition that clinical risk assessment is a key aspect of clinical decision-making have led to sustained efforts to standardise clinical risk assessment procedures in mental health. Standardised risk assessment tools have evolved to focus, among other things, on suicide and self-harm, violence, self-neglect, vulnerability and risk to children, although not all tools cover all risks.

At an organisational level, judging the quality of clinical risk management is notoriously difficult. The overall numbers of completed suicide among service users of any particular service are typically small and not amenable to statistical analysis.

Psychiatrists are well placed to improve the quality and safety of clinical risk management in the organisations in which they work. This article is intended as a practical guide to approaching this task in a mental healthcare organisation. It suggests a framework to organise the response and anticipates potential challenges. Essentially, there are three stages:

-

1 understanding expectations

-

2 evaluating the need for change

-

3 considering the challenges and proposing a way forward.

Understanding expectations

Ensuring that the workforce is fit for purpose is key to the success of any healthcare organisation. Mental health providers have articulated responsibilities for training staff and managing processes that are pertinent to risk. National bodies set guidance and standards for care and hold organisations to account. The spirit of reviewing clinical practice in relation to risk may be one of quality improvement within the organisation, but it is necessary to pay particular attention to external requirements that come from the wider health system. Guidance typically advises on good practice with reference to review of evidence, whereas standards outline a set of behaviours that must be followed.

National guidance

The Department of Health set out its priorities for risk assessment in England in Best Practice in Managing Risk (Department of Health 2009). This document, produced for the National Mental Health Risk Management Programme, was intended to help mental health practitioners and mental healthcare organisations develop their procedures and practice in working with clinical risks. The Department of Health conducted an extensive review of the risk management literature, particularly with regard to risk management tools. Further, it reviewed examples of practice from across the National Health Service (NHS) and identified instances of good practice. On the basis of this work, it proposed 16 best practice points for the effective management of risk. The report also described a range of risk assessment procedures and tools, but did not make any requirements for their implementation. Instead, organisations were allowed to develop their own policies and procedures, provided they were informed by the evidence base.

Risk assessment tools remain a controversial subject among clinicians. Critics point out their limited usefulness in predicting outcomes. In a report, the Royal College of Psychiatrists recommends that locally developed risk assessments should be abandoned altogether because they are felt to promote a ‘tick-box mentality’ (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2010). As an alternative, the College advises that widely validated, evidencebased tools be used and emphasises that they should not be applied in isolation, but be integrated into an overall biopsychosocial assessment.

The College's report is often understood as implying that evidence of predictive power should be sought, but evidence of efficacy in reducing unwanted outcomes would be more relevant to the clinical purpose of risk assessment. It appears that no single tool is recommended for use in some of the most relevant clinical settings, such as community crisis teams, and almost all studies focus on prediction or acceptability rather than the reduction of the unwanted outcomes. One notable exception is a study of the Brøset Violence Checklist (Reference Abderhalden, Needham and DassenAbderhalden 2008), which predicts violence over the next 12 hours in in-patients. The study showed a reduction in violence on wards where the checklist was used.

National standards

The National Health Service Litigation Authority (NHSLA) is a special health authority established in 1995 that administers schemes to cover liabilities for clinical negligence in England, so that NHS bodies can pool the costs for any ‘loss of or damage to property and liabilities to third parties for loss, damage or injury arising out of the carrying out of [their] functions’ (Department of Health 2002). The intention is that the administration of the scheme promotes high standards of care within the NHS in England and minimises the impact of any serious and untoward incidents.

This body essentially acts as an insurance firm for NHS organisations. All trusts, including foundation trusts, are required to make payments to the NHSLA. When significant incidents of negligence occur that are covered by the schemes, the NHSLA takes forward the administration of the process. Like most types of insurance, the amount paid by an individual organisation is stratified, with the organisations presenting the highest risks expected to provide a higher premium. The NHSLA is clear that this system of contribution provides an incentive to organisations to manage the risks that they present. Trusts that are able to demonstrate active management of their risks can significantly reduce their contributions to the NHSLA. Cost-effective organisations will provide the NHSLA with evidenced risk management plans, highlighting how they have met the defined standards to qualify for reduced contributions. Level 3 affords the lowest contribution and is the most difficult level to achieve.

For mental health and learning disability (intellectual disability) trusts, the NHSLA has defined 5 standards, each with 10 criteria, covering 50 areas of organisational risk (there are six standards in total, but standard 5 refers only to acute, community and non-NHS providers) (National Health Service Litigation Authority 2012). These organisations present a wide range of potential risks and the range of standards reflects this. They cover areas from hand hygiene and resuscitation to harassment and bullying and sickness absence. In addition, there are standards that are particular to mental health and learning disability settings, including rapid tranquillisation, absence without leave (AWOL) and clinical risk assessment. The criteria for clinical risk assessment are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1 Standard 6, criterion 3: clinical risk assessment

Mental health and learning disability trusts, like all healthcare providers in England, are regulated by the Care Quality Commission (CQC), whose responsibility it is to ‘make sure that the care people receive meets essential standards of quality and safety’ (Care Quality Commission 2010). It provides registration and regulation of NHS bodies and regularly monitors compliance with nationally defined quality standards. The CQC defines standards according to the types of services offered. Mental health and learning disability trusts are likely to be required to meet standards for a range of services. Examples include community-based services for people with mental health needs (so-called MHC services) and hospital services for people with mental health needs, learning disabilities and/or problems with substance misuse (MLS services) among others. Where the CQC finds that the standard of care provided by an organisation is below what is expected, they will work with commissioners and provider organisations to address this and use enforcement powers if necessary.

Outcome 4L from the CQC (Care Quality Commission 2010: p. 69) refers specifically to clinical risk and is required to be met for MHC, MLS and some other services:

‘People who use services who are thought to present a risk of suicide and homicide or harm to themselves or others have an ongoing, multi-disciplinary assessment and plan of care made:

-

• To determine whether they have a history of harm to themselves or others.

-

• To establish any risk of suicide and homicide or harm to themselves or others, including environmental risks, and how these can be minimised.'

Local response to national drivers

Although there remains continued appropriate debate regarding clinical risk assessment and management, there are a number of drivers that require providers to set out clear policies and procedures, including standards for documentation that need to be acknowledged. It is imperative that organisations come up with a solution. Clinicians can have a role in shaping the response to develop practices that are safe, clinically sensible and work for the benefit of service users. In England, the Department of Health, NHSLA and CQC documents are useful because they generate a series of essential rules that will shape policy locally. In summary, these are:

-

• risk assessment and management plans are necessary;

-

• organisations must have in place ‘tools/processes’ that are clearly described;

-

• organisations must monitor (audit) the implementation of their risk assessment and management practices; and

-

• as far as is practicable, tools/processes should be informed by the evidence base.

Evaluate the need for change and make a plan

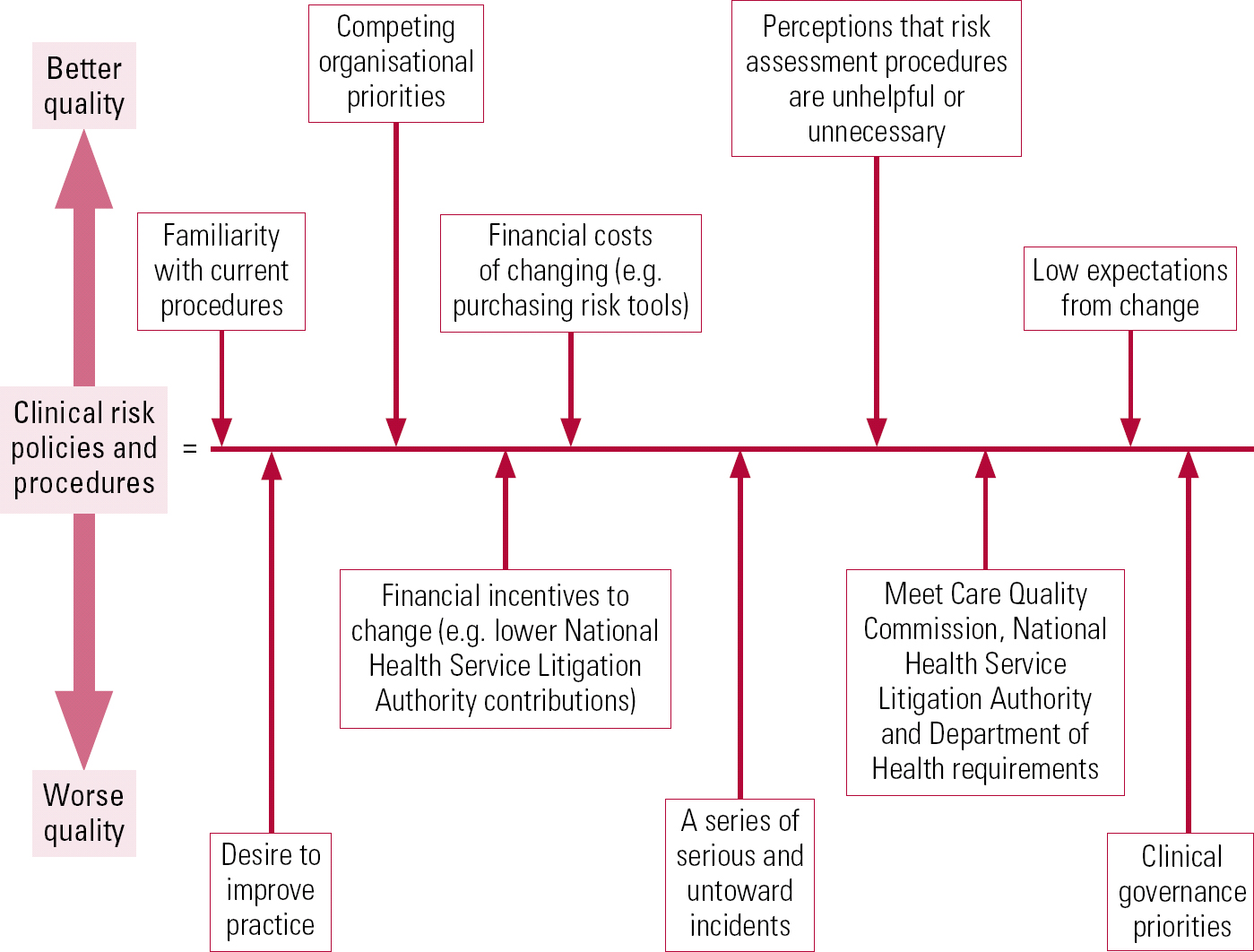

A useful first step in planning a strategy is to conduct a ‘force field analysis’ to describe the situation as it stands. This method is based on a concept originally described in psychology (Reference LewinLewin 1943) and helps to articulate the drivers for and against change of the present state (or ‘field of equilibrium’). In this case, the field of equilibrium may be defined as ‘clinical risk policies and procedures’ and the change aimed for is ‘better quality’. The field is then annotated, with the forces promoting or impeding change described. An example force field analysis for a typical mental healthcare provider (for revising clinical risk policies) is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig 1 Force field analysis for a typical mental healthcare provider (based on Reference LewinLewin 1943).

This exercise can be useful because it can contribute to structuring thinking to move the project forward. Questions about the present state can be posed that can help suggest actions:

-

• Which forces for change can be promoted? For example, should this area be prioritised through clinical governance? Can financial savings be achieved through obtaining a higher NHSLA level?

-

• Can new forces for change be identified? For example, can other stakeholders be found who might benefit from change?

-

• Which forces for resistance can be reduced? For example, can people's perceptions of risk assessment and management be changed?

-

• Which forces for resistance can be diverted to other areas? For example, does a potential solution need to be a purchased product or can it be created internally at no extra cost?

As the force field is examined in this way, a strategy to move forward should become clearer. To secure a change in practice and culture that is embraced by the organisation, the dos and don'ts in Box 1 may help in tackling the situation.

BOX 1 Dos and don'ts in securing a change in practice

-

• Do review current practice and need Is there a need to change? Is it going to be worth the effort? If so, you may need to convince others of this and you will need to know the details of context to back up your assertions

-

• Do review the literature You may need to know national guidance in more detail and evaluate the solutions that have been explored elsewhere

-

• Don't lose sight of what you are trying to achieve Devise a project plan and aspirations

-

• Do obtain the authority and organisational backing to take the plan forward Who are the key decision makers that will allow or block the changes you are proposing? It is likely that some of these people will want to check on progress over the following steps at intervals. Risk, quality or safety committees may need to endorse or revise aspects of the work. Keeping them informed and engaged can help to maintain momentum

-

• Don't go it alone Identify resources (particularly allies/colleagues)

-

• Do consider the service user and recovery agenda Get meaningful service user involvement and feedback, which can significantly improve quality and promote engagement

-

• Do clarify the potential options and evaluate these Produce a shortlist in the form of an options paper and articulate the proposed choices clearly

-

• Don't proceed without getting feedback on the options

-

• Do produce final recommendations You may need to obtain further feedback at this stage

-

• Do get the principles agreed and conduct a pilot before final implementation This will help to iron out any final unforeseen problems or indeed reduce the potential impact if this really is not the right way forward. We used a Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycle (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement 2008) for this stage of the work so that the product could be refined using feedback from clinicians and to increase the sense of ownership

Consider the challenges and propose a way forward

Mental healthcare providers are complex organisations. Services have much in common, but they have much to distinguish them too. Diversity among providers has increased as commissioning priorities in each region respond to local needs. This evolution has resulted in organisations looking quite different to one another, with bias in the types of services provided. Children's mental health services are one particular example – in some regions these are provided by community or acute trusts rather than mental health services. Secure forensic mental health, in-patient learning disability or specialist tertiary services may or may not fall within their remit. Our own organisation has changed significantly in recent years. As a foundation trust, learning disability services have expanded as the organisation has grown, and drug and alcohol services are now provided by a non- NHS organisation.

When developing policy, it is important to consider the needs of all the services that your organisation provides. To meet their aims, services use personnel with a wide range of skills and training, working in a range of environments from out-patient clinics to locked wards. It is imperative to liaise with stakeholders from across the organisation, including staff and service users, to think about key needs of risk assessment. Think about:

-

• What types of clinical risks will service users, carers and staff face?

-

• What is the demography of the population that the trust serves?

-

• What types of services does the organization provide?

-

• Within what kinds of environments does the trust operate?

-

• What is the skills mix of personnel, how are personnel used within the organisation and what are their training needs?

-

• Who provides risk assessment and how is it integrated into other assessment processes?

-

• What learning does clinical governance have to offer your trust? Have any themes emerged from serious incidents within the organisation?

This type of review is likely to give you a good insight into the requirements of your risk assessment processes. In doing this, a number of considerations may become apparent.

Organisational considerations

A ‘recognised risk tool’ or a home-grown solution

One leading dilemma is the tension between national requirements and the evidence base as it stands. If national policy requires a local response to risk assessment through the development of policy and procedure, but the evidence base requires further development to promote particular tools for clinical practice, what is an appropriate response? It may well be too early to abandon home-grown risk assessments for common mental health settings (such as out-patient clinics or crisis teams) altogether because there is no convincing successor. There remains a need for further research into the use of more comprehensive tools in these populations. In the meantime, from a good practice perspective, it is important to be mindful of the need for local acceptability and engagement and how the ability to adapt a tool to local needs may enhance ownership and use.

Time v. thoroughness pay-off

Generally, when using these approaches there is always a pay-off between the amount of time an assessment takes to complete and how thorough it is; tools that more thoroughly assess risks take the longest. When considering tools, it is worth assessing data on the time taken to complete the tool and to consider trialling some favoured tools in clinical settings to evaluate whether full implementation is realistic.

Training and good practice

Manufacturers of many of the commercially available tools can support organisations in setting up training around risk. Training is important because the utility of such tools is only as good as the clinicians who use them. It can also be a key factor in achieving buy-in and raising awareness of the tool across the organisation. All of the tools have strengths and weaknesses in practice and it is important to look at the characteristics of each and consider how they might help your organisation to deliver services to a standard to which it aspires. As yet, there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

Assessment v. management

Risk assessments are only worth doing if they are later acted on. Producing a management plan that is linked to the outcomes from the assessment is crucial. It should be noted that some tools include management as part of the process and some do not. It is important to consider how any risk assessment will inform the care that service users receive. If the management is not recorded as part of the risk assessment, how is it recorded? Is it in the care plan, a clinic letter or elsewhere? There should be a joined-up strategy.

How will you respond to the needs of special populations and services?

Some commercial manufacturers have risk tools they say have been developed for special populations such as child and adolescent mental health services or learning disability services. Some parts of your organisation may have taken their own risk assessment processes forward, for example the use of Historical, Clinical, Risk Management – 20 scale (HCR–20; Reference Webster, Douglas and EavesWebster 1997) in forensic services. The question remains whether decisions about risk assessment tools in specialist services be devolved to those services or be required to follow a standard procedure as well.

How will you respond to the organisational challenges for recovery-oriented practice with respect to risk?

Many organisations are orienting their services in line with recovery principles. The Centre for Mental Health (Reference Shepherd, Boardman and BurnsShepherd 2009) highlights ten key organisational challenges for services in this respect. Challenge six refers specifically to risk assessment: ‘Changing the way we approach risk assessment and management’. It may be necessary for your organisation to consider the relative merits of differing tools with respect to recovery and to think about how it may help service delivery in this regard.

What are the information technology capabilities of your organisation and how will risk assessment be recorded?

Electronic record-keeping is rapidly becoming the norm. Some risk tools are now compatible with electronic records, and others can be completed online. In some cases, electronic records can be built that are tailored to the needs of the organisation and risk tools can be constructed accordingly.

Perspectives on clinical risk management in mental health trusts

To be able to develop the most effective processes, it is helpful (for clinicians) to be mindful of the broader context to estimate the potential impact that new processes can have. National initiatives describe the fundamentals of what should be done, but much can be learnt from key people within an organisation. This can inform better resolutions and provide advantages in terms of promoting accurate and meaningful implementation of better practice. Medical managers and operational managers can give insight into the history and circumstances of the organisation and anticipate potential challenges with views of how they may be overcome. The risk department or risk managers will have expertise in managing organisational risk and should have particular intelligence regarding serious and untoward incidents and other information relevant to designing the system. They should also have knowledge of staff training arrangements, including details such as how many staff are trained and what resources are available to meet the training needs within the organisation. Trust solicitors and legal departments are likely to have views on defensible arrangements and may be able to advise in this regard.

Our own experience

In our own trust, we took as a starting point the six tools recommended in Best Practice in Managing Risk (Department of Health 2009) for assessing multiple risks. Our aim was to develop a set of procedures that would be applicable to all services. We familiarised ourselves with each of these, then drew up a shortlist. This included Functional Analysis of Care Environments (FACE; www.face.eu.com), the Galatean Risk and Safety Tool (GRiST; Reference BuckinghamBuckingham 2007) and the Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability (START) instrument; Reference Webster, Martin and BrinkWebster 2009), as well as modifying our own home-grown tool. In our view, these tools most clearly met our needs for reasons of clinical utility, integration with our current systems, evidence base and cost to the organisation.

The shortlist was examined more thoroughly and put through a series of further tests. In collaboration with colleagues from across our organisation, we outlined the set of characteristics we hoped for and other considerations. We wanted the tool to support clinicians in decisionmaking, to improve the quality of assessments and management plans, to promote recovery, and to be acceptable to service users and carers. Additionally, we needed to be mindful of affordability, the training needs of staff and other implementation considerations.

In each case, we contacted clinicians using these systems in other organisations and liaised with the manufacturers. In doing this, we sought to establish how each of the tools performed across all of our defined domains and then produced a summary report of our findings. Based on this, a decision was made by the trust to pursue the modification of our home-grown solution, informed by the evidence base, as no single tool stood out as being superior for our requirements.

Conclusions

Ultimately, when it comes to developing clinical risk management strategies, it is unlikely that there will be only one right answer. However, some approaches may bring a distinct improvement to the quality of practice as it stands. The opportunity to revise policy and procedures within a mental health service may afford a real possibility of meaningful change locally. Approaching the challenges in a considered way can maximise the positive outcomes and secure engagement in the process to the benefit of service users and staff alike.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Regarding the Department of Health documentBest Practice in Managing Risk :

-

a there are 15 best practice points

-

b they review risk assessment procedures but not risk assessment tools

-

c they take the form of national guidance

-

d they do not advocate consideration of the evidence base in developing clinical risk processes

-

e they do not allow trusts to develop their own policy and procedures.

-

-

2 Regarding the National Health Service Litigation Authority:

-

a there are four levels

-

b it is one of the strategic health authorities

-

c level 1 is the most difficult level to achieve

-

d for mental health trusts, there are six standards, each with ten criteria

-

e examples of criteria include ‘harassment and bullying’ and ‘absence without leave’.

-

-

3 For clinical risk assessment and management, national standards and guidance stipulate that:

-

a risk assessment and management plans are unnecessary

-

b organisations must have ‘tools/processes’ in place that are commercially available

-

c organisations must monitor (audit) the implementation of their risk assessment and management practices

-

d as far as is practicable, tools/processes should include tick boxes

-

e policies must be revised once every 5 years.

-

-

4 The Institute for Healthcare Improvement 5 Million Lives campaign:

-

a started in 2001

-

b targeted patients with mental health problems

-

c encouraged standardisation and prevention

-

d built on the work done in the 4 million lives campaign

-

e was a UK initiative.

-

-

5 Force field analysis:

-

a was originally described by Ritchey

-

b is based on concepts originally described in sociology

-

c is suitable for use in risk assessment

-

d requires a field of equilibrium

-

e can estimate the likelihood of future violence.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 c | 2 e | 3 c | 4 c | 5 d |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.