It is important to be clear about what constitutes a ‘binge’. Binges (sometimes termed bulimic episodes) have two essential features: first, a large amount of food is eaten for the circumstances; and second, there is a sense of a lack of control. The DSM–IV definition is as follows (American Psychiatric Association 1994):

An episode of binge-eating is characterized by both of the following: eating, in a discrete period of time (e.g. within any 2-hour period), an amount of food that is definitely larger than most people would eat during a similar period of time and under similar circumstances; and a sense of lack of control over eating during the episode (e.g. a feeling that one cannot stop eating or control what or how much one is eating).

Note that the evaluation of the amount eaten is contextual; that is, account is taken of what would be the usual amount to eat under the circumstances. In clinical practice some patients describe binges that involve the consumption of modest amounts of food, this being especially true of patients with anorexia nervosa. Such episodes (termed ‘subjective bulimic episodes’ or ‘subjective binges’) do not fulfil the current DSM definition of a binge, although the sense of a lack of control is similar. Figure 1 shows the binge eating of a patient with bulimia nervosa.

Eating disorder diagnoses

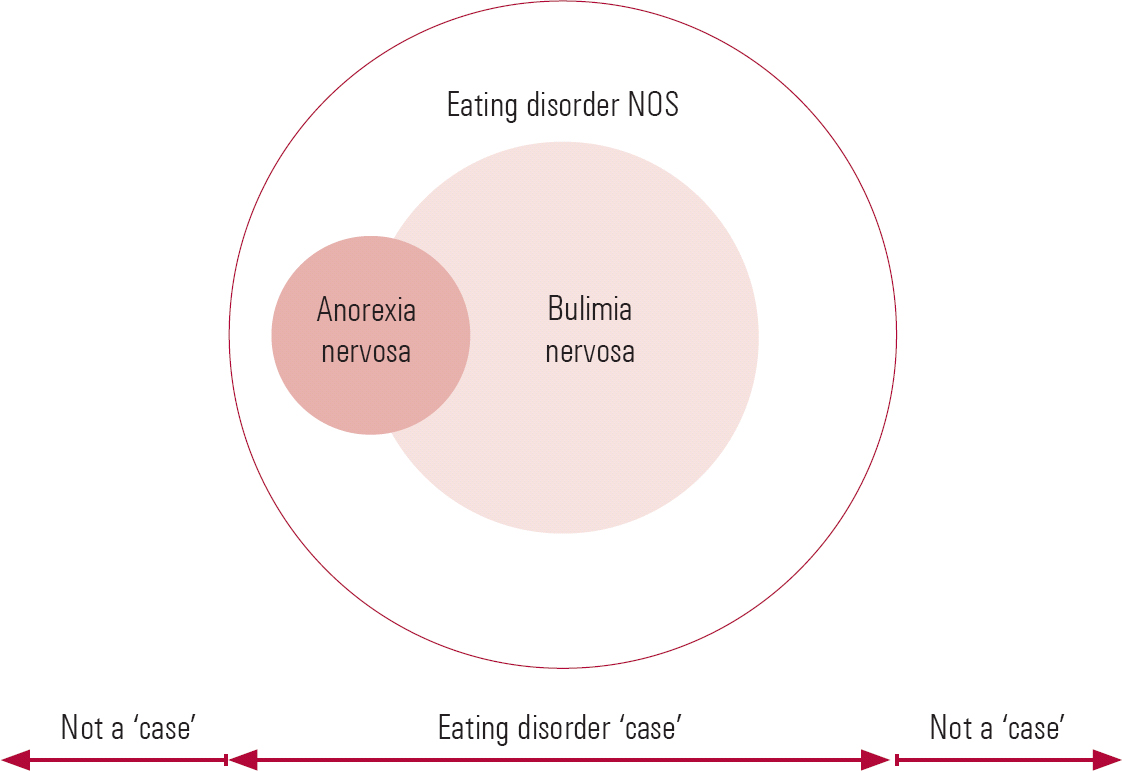

The DSM–IV recognises three eating disorders: anorexia nervosa; bulimia nervosa; and eating disorder not otherwise specified (NOS), which includes binge eating disorder. As noted, binge eating is required for the diagnosis of one of these disorders (bulimia nervosa) and may be a feature of the other two. It is helpful to illustrate diagrammatically the relationship between these three diagnoses (Fig. 2). The two overlapping inner circles represent anorexia nervosa (the smaller circle) and bulimia nervosa (the larger circle); the area of potential overlap is occupied by those people who would meet the diagnostic criteria for both disorders. When this occurs, the DSM–IV ‘trumping’ rule is applied whereby the diagnosis of anorexia takes precedence over that of bulimia. The outer circle defines the boundary of eating disorder ‘caseness’, namely the boundary between having a clinically significant eating disorder and having a lesser, non-clinical problem with eating. Within this outer circle, but outside the two inner circles, lies eating disorder NOS.

Anorexia nervosa

Three features must be present to meet diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa. First, the person should be significantly underweight and this should be the result of their own efforts. A widely used weight threshold is a body mass index BMI <17.5 kg/m2 (where the BMI is calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m) squared (m2)). Second, women should not menstruate (unless they are taking an oral contraceptive). Third, the person should be extremely concerned about their shape or weight, or both. Rather than worrying about being underweight, however, the person should be afraid of gaining weight. Self-worth should be judged largely or even exclusively in terms of shape or weight.

About a quarter of patients with anorexia binge eat. Many more have subjective binges.

Bulimia nervosa

Binge eating is the cardinal feature of bulimia nervosa and is required for a diagnosis. Three features have to be present to meet the diagnostic criteria for bulimia. First, the person must have frequent binges as described above, i.e. genuinely large amounts of food must be consumed with an accompanying sense of loss of control. Second, the person must regularly use extreme measures for controlling shape or weight. These include self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives or diuretics, over-exercising and intense dieting or fasting. Third, the person must be extremely concerned about their shape or weight, or both, judging their self-worth largely or even exclusively in terms of them. These attitudes to shape and weight are essentially the same as those seen in anorexia nervosa.

There is one other exclusionary requirement: that the person should not meet diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa (i.e. the DSM–IV trumping rule).

Eating disorder not otherwise specified

The third eating disorder diagnosis is the much neglected residual category ‘eating disorder NOS’. There are two steps in making the diagnosis: first, it must be determined that there is an eating disorder of clinical severity; and second, it must be established that the diagnostic criteria of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are not met (Reference Fairburn and BohnFairburn 2005a). Thus, the diagnosis is made by exclusion.

Clinical descriptions of eating disorder NOS indicate that, just as in anorexia and bulimia, most patients are young women and many have had either anorexia or bulimia, or both, in the past. Their clinical features closely resemble those seen in anorexia and bulimia, albeit at slightly different levels or in different combinations (Reference Fairburn, Cooper and BohnFairburn 2007). Binge eating is present in about a half of these patients.

Binge eating disorder

The American Psychiatric Association (1994) has proposed that a third specific eating disorder be recognised in addition to anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. This provisional diagnosis is termed ‘binge eating disorder’. It is intended for people with recurrent episodes of binge eating in the absence of the extreme methods of weight control seen in bulimia and anorexia. This proposal was controversial when it was first suggested and remains so today (Reference Stunkard and AllisonStunkard 2003;Reference Wilfley, Wilson and AgrasWilfley 2003; Reference WalshWalsh 2007). At present, binge eating disorder is not an established DSM–IV diagnosis and therefore eating disorders of this type are still classified officially as eating disorder NOS.

In clinical samples, people with binge eating disorder are usually rather older than those with anorexia, bulimia or eating disorder NOS, most are middle-aged and about a quarter to a third are male. The majority have comorbid obesity and it is often the combination of this and their binge eating that leads them to seek help.

Clinical prevalence

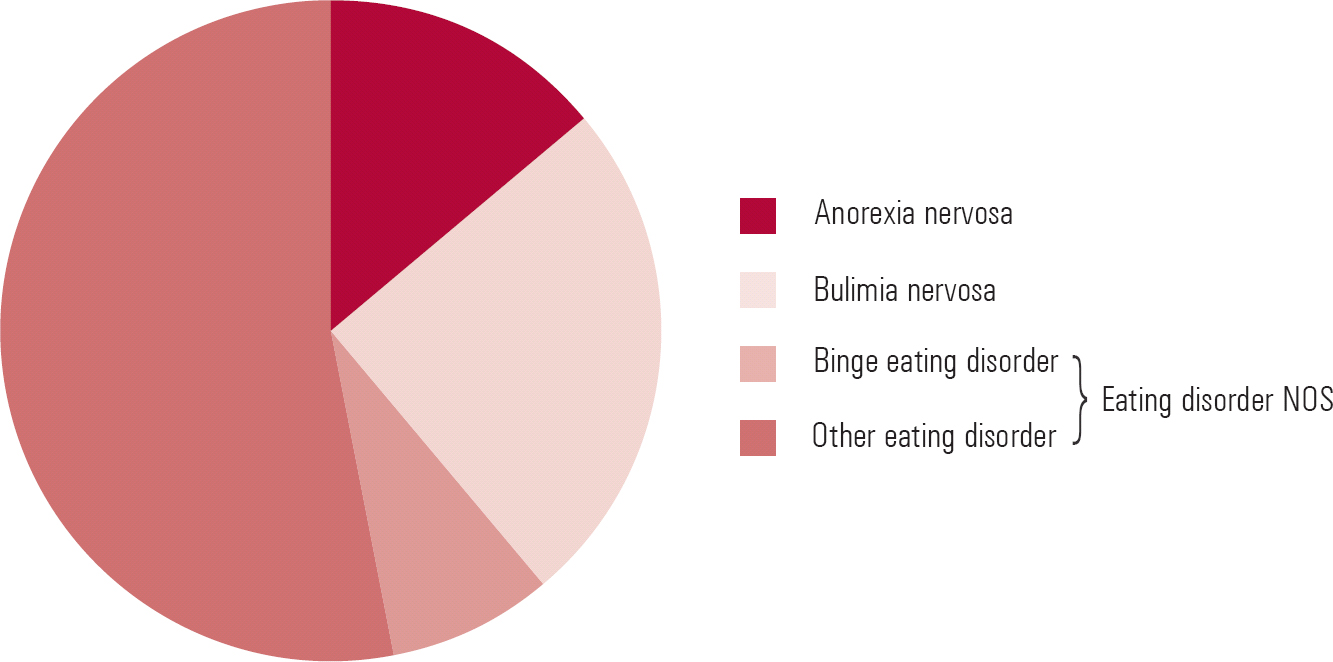

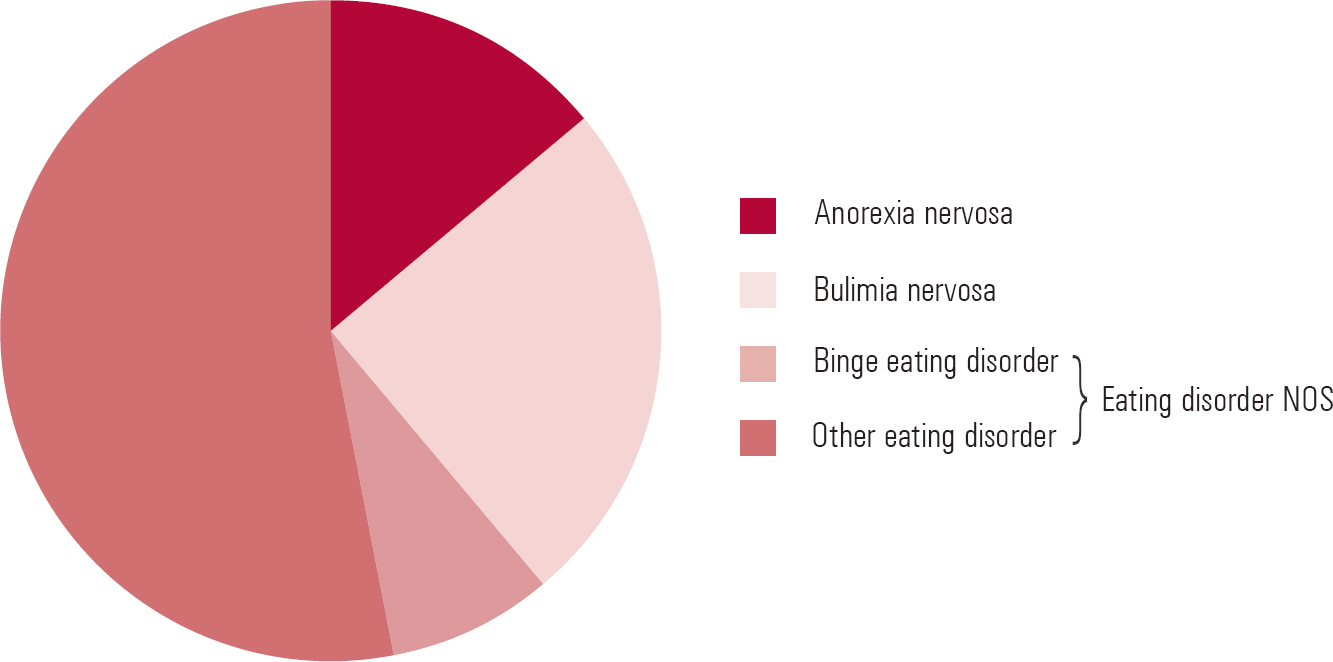

The relative prevalence of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and eating disorder NOS among patient samples is contrary to what one might expect bearing in mind the current DSM classification scheme (Fig. 3). Eating disorder NOS, the residual category, is by far the most common presentation, constituting about 60% of cases seen in out-patient settings (Reference Fairburn and BohnFairburn 2005a) and around 75% of eating disorder cases in the community (Reference Machado, Machado and GonçalvesMachado 2007). Bulimia is the next most common, representing about a third of cases, and the remainder are cases of anorexia nervosa. Diagnostic criteria for binge eating disorder are met in less than 10% of cases.

Evidence-based treatment

Over the past 25 years, eating disorders have attracted considerable research attention. This was stimulated by the emergence in the late 1970s of large numbers of bulimia nervosa cases and subsequent claims that the disorder responded to both cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and antidepressant medication. Since then, bulimia has been the focus of over 70 randomised controlled trials and as a result evidence-based treatment is now possible.

More recently, the treatment of binge eating disorder has also attracted research attention, with many of the treatments for bulimia being applied to this condition. Evidence-based treatment of binge eating disorder is also possible, although the evidence is less strong than for bulimia.

In contrast, there has been relatively little research on the treatment of anorexia, in part because of the rarity of the condition and in part because its management poses many logistical problems. Few comparative trials have been reported and several have produced inconclusive results. The most positive outcomes have been achieved using a specific form of family therapy (the Maudsley Model) with adolescent patients with disorders of recent onset (Reference Wilson, Grilo and VitousekWilson 2007a), but comparable success has not been achieved with more established cases. Thus, evidence-based treatment of anorexia is barely possible and current recommendations about appropriate treatment are still based on expert opinion rather than robust data (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 2004; Reference FairburnFairburn 2005b).

Until recently there were no studies on the treatment of eating disorder NOS, but emerging evidence suggests that an enhanced form of the existing evidence-based treatment for bulimia designed to be suitable for the full range of eating disorders is just as effective for patients with eating disorder NOS (Reference Fairburn, Cooper and DollFairburn 2008a).

Management of bulimia nervosa

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines

Distilling what has been learned from large bodies of research is not straightforward. As readers will be aware, conventionally this has been done in the form of narrative reviews in which the authors describe and evaluate research findings, as for example did Reference Wilson, Grilo and VitousekWilson et al (2007a). Although such reviews are of value, they are susceptible to multiple forms of bias. Systematic reviews, in which a standardised approach is taken to the identification of all relevant studies and the synthesis of their findings, attempt to avoid this bias. Recently, several systematic reviews have been published on the treatment of bulimia. That commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 2004) is particularly rigorous and, as with all NICE systematic reviews, it provides evidence-based guidelines for clinical management. In essence, three main conclusions emerged from this review, and it is worth noting that they are consistent with the most recently published systematic review on the subject (Reference Shapiro, Berkman and BrownleyShapiro 2007). The NICE conclusions are as follows.

First, the leading treatment for bulimia nervosa is a specific form of CBT. There is strong research support for this treatment. Indeed, such is the strength of the evidence that NICE recommends that ‘cognitive–behavioural therapy for bulimia nervosa, a specifically adapted form of cognitive–behavioural therapy, should be offered to adults with bulimia nervosa’ across the National Health Service.

Second, interpersonal psychotherapy offers an evidence-based alternative to CBT and involves about the same amount of therapist contact (Reference Fairburn, Garner and GarfinkelFairburn 1997). Since interpersonal psychotherapy has considerably less empirical support than CBT and it takes longer to achieve comparable effects, NICE recommends that it ‘should be considered as an alternative to cognitive–behavioural therapy, but patients should be informed it takes 8–12 months to achieve results comparable to cognitive–behavioural therapy’.

Third, antidepressant drugs and certain self-help programmes (preferably used with some form of professional support) both have some efficacy as treatments for bulimia and are relatively straightforward to implement. However, since the evidence suggests that few patients make a full and lasting response to either treatment, NICE recommends that these treatments be viewed as possible first steps in management; NICE further specifies that fluoxetine is the antidepressant drug of choice, at a dose of 60 mg/day.

It is worth noting that these recommendations apply to adults, as at the time of the NICE review there were no published controlled trials focusing exclusively on the treatment of adolescents with bulimia. Two randomised controlled trials of family-based treatments for adolescents have since been published. In the first of these, which included young people with bulimia nervosa and eating disorder NOS, family-based treatment was compared with a guided self-help form of CBT (Reference Schmidt, Lee and BeechamSchmidt 2007). In the second study, in adolescents with bulimia nervosa and subthreshold bulimia nervosa strictly defined, family-based treatment was compared with supportive psychotherapy (Reference Le Grange, Crosby and RathouzLe Grange 2007). Although family-based treatment showed an advantage over supportive psychotherapy, very few differences emerged when compared with cognitive–behavioural self-help. Thus, further work is required before firm evidence-based treatment guidelines can be proposed for adolescents.

Stepped care

The NICE guidelines may be translated into a stepped care approach to the clinical management of bulimia nervosa.

Step one

As an initial step in treatment, antidepressant medication may be used. Most antidepressant drugs have an ‘antibulimic’ effect, resulting in a sizeable decrease in the frequency of binge eating and vomiting. This effect becomes apparent rapidly. As recommended, the drug generally used is fluoxetine 60 mg, taken in the morning. This is well tolerated and most patients experience few adverse effects after the first week. Antidepressants such as fluoxetine can also be used to treat a comorbid depressive disorder. In our experience, comorbid clinical depressions often go undetected in these patients. Few people with bulimia make a full response (in terms of binge eating and vomiting) to antidepressant medication and the effect tends to wear off whether or not the person continues on the drug. Thus, antidepressant medication is rarely sufficient on its own. This is probably because these drugs fail to moderate the characteristic extreme and brittle dieting which largely maintains binge eating.

An alternative, or additional, first step is to recommend a self-help book such as Getting Better Bit(e) by Bit(e) (Reference Schmidt and TreasureSchmidt 1993) and Overcoming Binge Eating (Reference FairburnFairburn 1995). There is evidence to support the use of both these books, especially if they are accompanied with some external support and encouragement, so-called ‘guided self-help’ (Reference Sysko, Walsh, Latner and WilsonSysko 2007). This can be provided by any clinical professional (e.g. general practitioner or practice nurse). However, as with antidepressant medication, few patients will make a full response.

Although, in principle, both antidepressant medication and self-help are relatively easy to implement and so would seem well suited for use in primary care, in practice this is more difficult (e.g. Reference Walsh, Fairburn and MickleyWalsh 2004). Referral for specialist treatment is generally to be preferred but, while patients are waiting for specialist treatment, one or both of these treatments may be tried (e.g. Reference Palmer, Birchall and McGrainPalmer 2002).

Step two

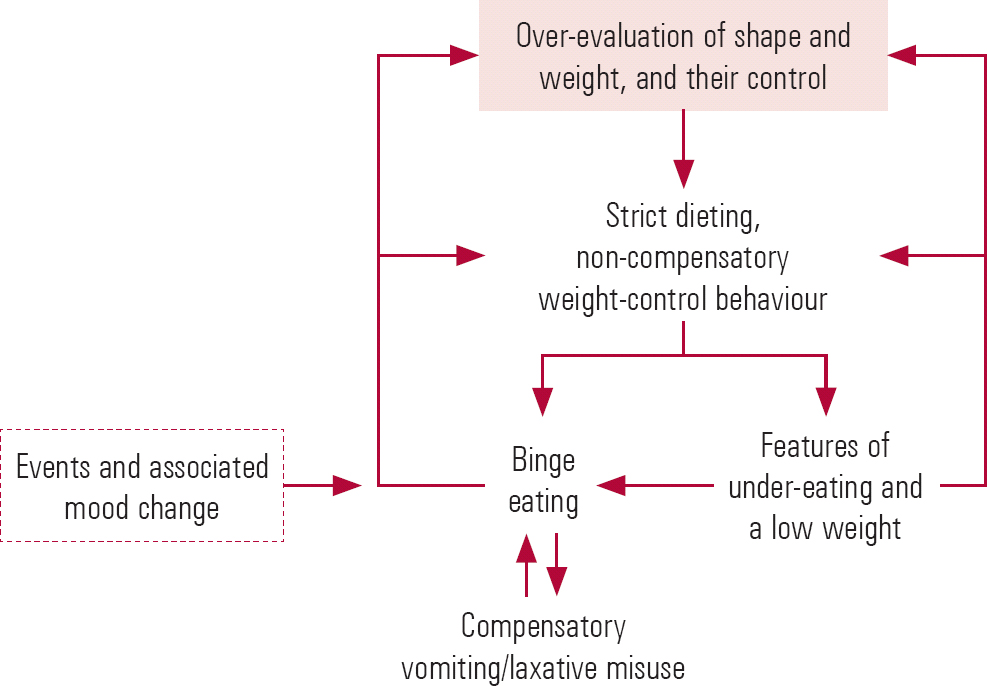

As noted by NICE, the treatment of choice for bulimia nervosa is a specific form of CBT (Reference Fairburn, Marcus, Wilson, Fairburn and WilsonFairburn 1993). This treatment is based on a cognitive–behavioural account of the processes maintaining bulimia, which has recently been extended to all eating disorders. This transdiagnostic theory (Reference Fairburn, Cooper and ShafranFairburn 2003) highlights the fact that patients with eating disorders share the same distinctive psychopathology and suggests that common transdiagnostic mechanisms are involved in the persistence of these disorders. According to the theory, people with bulimia, in common with individuals with other forms of eating disorder, over-evaluate the importance of their shape and weight and their ability to control them, and it is this dysfunctional scheme of self-evaluation that is of central importance in maintaining these disorders. Whereas most people evaluate themselves on the basis of their perceived performance in a variety of domains of life, people with eating disorders judge themselves primarily in terms of their shape and weight and their ability to control them. Most of their other clinical features can be understood as stemming directly from this core psychopathology, including the extreme weight-control behaviour (viz. the dieting, self-induced vomiting, laxative misuse and over-exercising), the various forms of body checking and avoidance, and the preoccupation with thoughts about eating, shape and weight. Figure 4 provides a representation (or formulation) of the main processes involved in the maintenance of eating disorders.

The only feature that is not obviously a direct expression of the core psychopathology is binge eating. Cognitive–behavioural theory proposes that binge eating is largely a product of attempts to adhere to multiple extreme, and highly specific, dietary rules. These patients' tendencies to react in a negative and extreme fashion to the (almost inevitable) breaking of these rules results in their interpretation of even minor dietary slips as evidence of poor self-control. Patients respond to this perceived lack of self-control by temporarily abandoning their efforts to restrict their eating. This produces a highly distinctive pattern of eating in which attempts to restrict eating are repeatedly interrupted by episodes of binge eating. The binge eating maintains the core psychopathology by intensifying patients' concerns about their ability to control their eating, shape and weight. It also encourages further dietary restraint, thereby increasing the risk of further binge eating.

Three further processes also maintain binge eating. First, difficulties in the patient's life and associated mood changes increase the likelihood that they will break their dietary rules. Second, binge eating temporarily ameliorates such mood states and distracts patients from thinking about their problems, and so it can become a way of coping with day-to-day difficulties. Third, if the binge eating is followed by compensatory vomiting or laxative misuse, the binge eating pattern is maintained. This is because patients' mistaken belief in the effectiveness of such ‘purging’ undermines a major deterrent against binge eating (in reality, purging has little effect on energy absorption).

Although CBT is the most potent treatment for bulimia nervosa, less than half of patients make a full and lasting recovery (Reference Wilson, Fairburn, Nathan and GormanWilson 2007b). Recently an enhanced form of the treatment has been developed (Reference Fairburn, Cooper, Shafran and BarlowFairburn 2008b,Reference Fairburnc). Although derived from the original CBT for bulimia nervosa, this treatment uses a variety of strategies and procedures to improve treatment adherence and outcome, and to identify and address obstacles to change. In addition, on the basis of the transdiagnostic theory of the maintenance of eating disorders, the treatment has been adapted to make it suitable for all forms of eating disorders and not just bulimia. The treatment exists in two forms: a focused form that concentrates exclusively on eating disorder psychopathology, and a broad form which also addresses, as needed, three commonly encountered external barriers to change (clinical perfectionism, core low self-esteem and interpersonal difficulties) which may occur in some cases. Almost all cases of eating disorders are complex as most people have significant other problems, including other Axis I disorders (the most common being mood disorders and substance misuse), personality disorders and physical complications. Enhanced CBT is designed to cope with these problems, many of which can be managed while providing treatment (Reference Fairburn, Cooper, Shafran and BarlowFairburn 2008b).

Box 1 lists the four stages and main elements of enhanced CBT (for a detailed description see Reference Fairburn, Cooper, Shafran and BarlowFairburn 2008b,Reference Fairburnc). The treatment is time limited, generally involving 20 sessions over 4–5 months. As it is highly individualised, it is best delivered on a one-to-one basis.

As the NICE guidelines note, interpersonal psychotherapy is an evidence-based alternative to CBT. Interpersonal psychotherapy is a short-term, focal psychotherapy developed by Reference Klerman, Weissman and RounsavilleKlerman and colleagues (1984) as a treatment for depression. The focus of the treatment is on helping patients identify current interpersonal problems and encouraging them to find solutions. Clinical experience suggests that interpersonal psychotherapy operates by improving interpersonal functioning and thereby enhancing self-esteem. This erodes patients' dependence on controlling shape and weight as a means to bolster their self-worth. As a result, they diet less intensively and the eating disorder gradually breaks down. One weakness of interpersonal psychotherapy is that it is much slower to work than CBT. Guidelines on implementing this variant of interpersonal psychotherapy have been published (Reference Murphy, Straebler, Cooper, Dancyger and FornariMurphy 2009).

Step three

It is at this point that evidence-based management breaks down. There is no evidence-based treatment for patients who fail to respond to CBT or interpersonal psychotherapy. Some benefit from a period of day-patient or in-patient treatment. The other indications for hospital admission are depression of such severity that out-patient treatment is not possible and poor physical health (e.g. severe electrolyte disturbance).

BOX 1 Core elements of enhanced cognitive–behavioural therapy

Stage one

To engage the patient in treatment and change. Appointments are twice weekly for 4 weeks and involve the following key procedures:

-

• jointly creating a formulation of the processes maintaining the eating disorder

-

• establishing real-time monitoring of eating and other relevant thoughts and behaviour

-

• providing education about body weight regulation and fluctuations, the physical complications and ineffectiveness of self-induced vomiting and laxative misuse as a means of weight control, and the adverse effects of dieting

-

• introducing weekly weighing

-

• introducing a pattern of regular eating

-

• involving significant others to facilitate treatment if appropriate

Stage two

This is a transitional stage generally comprising two appointments, each a week apart, with the following elements:

-

• jointly reviewing progress

-

• identifying barriers to change

-

• modifying the formulation as needed

-

• planning stage three

Stage three

Eight weekly appointments to address the key mechanisms maintaining the eating disorder:

-

• over-evaluation of shape and weight:

-

• providing education about over-evaluation and its consequences

-

• reducing unhelpful body checking and avoidance

-

• re-labelling unhelpful thoughts or feelings such as ‘feeling fat’

-

• developing previously marginalised domains of self-evaluation

-

• exploring the origins of the over-evaluation

-

• Dietary restraint:

-

• changing inflexible dietary rules into flexible guidelines

-

• introducing previously avoided food

-

• Event-triggered changes in eating:

-

• developing problem-solving skills to directly tackle such events

-

• developing skills to accept and modulate intense moods

Stage four

To ensure that progress made in treatment is maintained and that the risk of relapse is minimised. There are three appointments, each 2 weeks apart, and a single review appointment 20 weeks after treatment has finished. In the three appointments the following key procedures are addressed:

-

• providing education about realistic expectations

-

• devising a short-term plan for the months following treatment

-

• devising a long-term plan to minimise relapse in the future

(Adapted from Reference Fairburn, Cooper, Shafran and BarlowFairburn 2008b)

If admission is indicated, it should always be viewed as a preliminary to good out-patient care. Clinicians should beware of being misled by the non-specific clinical improvement that usually accompanies admission. This merely reflects the influence of the hospital environment. It may not persist following discharge.

Management of other binge eating problems

Binge eating disorder

The treatment of binge eating disorder has been the focus of a recent narrative review (Reference Mitchell, Devlin and De ZwaanMitchell 2008) and two recent systematic reviews (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 2004; Reference Brownley, Berkman and SedwayBrownley 2007). The NICE systematic review, conducted by the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, resulted in three evidence-based recommendations that closely resemble those for bulimia nervosa.

First, the leading treatment for binge eating disorder is a form of CBT similar to that used to treat bulimia nervosa (Reference Fairburn, Marcus, Wilson, Fairburn and WilsonFairburn 1993) and it should be offered to these patients.

Second, other psychological treatments for binge eating disorder may be offered, including a variant of interpersonal psychotherapy (Reference Wilfley, Welch and SteinWilfley 2002) and a simplified form of dialectical behaviour therapy (Reference Telch, Agras and LinehanTelch 2001), although the evidence supporting them is modest.

Third, antidepressant drugs and certain self-help programmes (preferably used with some form of professional support) both have some efficacy as treatments for binge eating disorder and are relatively straightforward to implement – NICE recommended that they be viewed as possible first steps in management.

Certain other points need to be made about the management of binge eating disorder. First, binge eating tends to be highly responsive to treatment. Many interventions seem to be helpful and there is a sizeable placebo response rate. Second, guided cognitive–behavioural self-help appears to be almost as effective as full-scale CBT (Reference GriloGrilo 2006) and it is therefore an option worth serious consideration. Third, many of these patients present with comorbid obesity and this is often of more concern to them than the binge eating. Surprisingly, eliminating binge eating has little effect on body weight. This is because these patients overeat in general (and under-exercise), and their binge eating makes only a small contribution to their day-to-day energy surplus. The management of their accompanying excess weight is therefore a pressing clinical problem. At present it is not clear how best to combine weight management with treatment directed at the binge eating. A new cognitive–behavioural treatment for obesity has been designed to treat both problems in tandem (Reference Cooper, Fairburn and HawkerCooper 2003); emerging research findings suggest that this treatment is effective for the binge eating and also produces short-term weight loss, but, in common with other treatments for obesity, the weight lost is regained in the longer term. Lastly, there is emerging evidence that drugs other than antidepressants benefit these patients (Reference GriloGrilo 2006). These include the appetite suppressant sibutramine and the anticonvulsant topiramate, both of which appear also to produce concomitant weight loss in the short term. More rigorous and longer-term studies of these drugs are needed before they can be recommended.

Anorexia nervosa

As noted, it is barely possible to make evidence-based recommendations regarding the management of anorexia nervosa (Reference FairburnFairburn 2005b), and there has been no research on the treatment of the small subgroup of these patients that binge eat. Studies of the prognosis of anorexia usually identify those who binge eat or vomit as having a worse outcome but it may be questioned whether this is still the case now that there are treatments (especially CBT) that have been designed to address the mechanisms that maintain binge eating.

Eating disorder not otherwise specified

Lastly, there is the large number of patients with eating disorder NOS who binge eat. As mentioned, there is emerging evidence that these patients respond well to the enhanced, transdiagnostic form of CBT described earlier (Reference Fairburn, Cooper, Shafran and BarlowFairburn 2008b).

Conclusions

Binge eating occurs across the entire range of eating disorders. It is required for the diagnosis of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder but it is also seen in many cases of ‘eating disorder not otherwise specified’ (usually referred to as ‘eating disorder NOS’ or ‘atypical eating disorders’) and in some cases of anorexia nervosa. As discussed, there are treatments (especially CBT) that address the mechanisms that maintain binge eating and there are now evidence-based recommendations for the treatment of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. As yet there are no similar recommendations for the treatment of eating disorder NOS or anorexia nervosa, although recent evidence suggests that an enhanced transdiagnostic form of CBT is effective for the treatment of eating disorder NOS.

MCQs

-

1 Binge eating is required for a diagnosis of:

-

a anorexia nervosa

-

b eating disorder NOS

-

c bulimia nervosa

-

d pica

-

e obesity.

-

-

2 The leading evidence-based treatment recommended by NICE for bulimia nervosa is:

-

a interpersonal psychotherapy

-

b a specific form of CBT

-

c in-patient treatment

-

d antidepressant drugs

-

e self-help.

-

-

3 In binge eating disorder:

-

a overeating does not occur

-

b weight restoration is an important goal

-

c self-induced vomiting occurs frequently

-

d excessive exercise is a major problem

-

e obesity is often a significant co-existing clinical problem.

-

-

4 Interpersonal psychotherapy:

-

a is a treatment only for depression

-

b is not used in the treatment of bulimia nervosa

-

c involves many more sessions than CBT

-

d is an alternative to CBT but is slower to work

-

e focuses on dieting.

-

-

5 The most common eating disorder seen in clinical practice is:

-

a eating disorder NOS

-

b anorexia nervosa

-

c bulimia nervosa

-

d purging disorder

-

e binge eating disorder.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | f | a | f | a | f | a | f | a | t |

| b | f | b | t | b | f | b | f | b | f |

| c | t | c | f | c | f | c | f | c | f |

| d | f | d | f | d | f | d | t | d | f |

| e | f | e | f | e | t | e | f | e | f |

FIG 1 Binge eating: a typical food-monitoring record of a patient with bulimia nervosa. *, eating regarded as excessive by the patient, with several in immediate succession indicating a binge; V, vomiting; L, laxative.

FIG 2 Relationship between anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and eating disorder NOS (redrawn with permission from Reference Fairburn and BohnFairburn 2005a).

FIG 3 Relative prevalence of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and eating disorder not otherwise specified (NOS) in out-patient samples. Binge eating disorder is at present still a subcategory of DSM–IV eating disorder NOS (data from Reference Fairburn and BohnFairburn 2005a).

FIG 4 Transdiagnostic cognitive–behavioural formulation of maintenance of eating disorders (Reference FairburnFairburn 2008c).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.