…to live without certainty, and yet without being paralysed by hesitation, is perhaps the chief thing.

(Bertrand Reference RussellRussell 1945)

Decisions form the bridge from knowledge to action. Many decisions require minimal effort, but psychiatrists are often faced with complex dilemmas, such as whether to admit a patient to hospital, whether to allow leave from hospital or whether to trial a medication that has serious side-effects. Such dilemmas are characterised by two key features:

-

• uncertainty with respect to the relative probabilities of the various outcomes that may follow: for example, how likely is it that this patient will abscond if granted leave?

-

• an inherent and inevitable level of risk because whatever decision is made, there are potential harms as well as benefits.

Whereas risk assessment is now established as a core skill for psychiatrists, the judgement and decision-making skills required to translate assessment knowledge into clinical action have only recently crossed the gap from academic psychology into medical training (Reference Del Mar, Doust and GlasziouDel Mar 2006). Unsophisticated thinking about decision-making is correspondingly common and so it is not unusual for the outcome of a risk decision (e.g. a patient treated at home dying by suicide) to be taken as a measure of the quality of the decision-making carried out before that outcome.

This article seeks to enhance skills in decision-making processes by providing a simple framework for use in clinical practice and an overview of the ways in which clinicians and managers can be unwittingly misled into suboptimal practice.

Intuition and reason

Classically, intuitive decision-making based on ‘what feels right’ has been considered to be dialectically opposed to rational approaches that methodically calculate an appropriate choice based on cold logic (Box 1). Rational decision-making depends on relatively slow, emotionally neutral cognitive processes, which require conscious effort (Reference KahnemanKahneman 2003). Their application to decision-making is exemplified by classical decision analysis, according to which choices between options are made according to estimates of expected utility (Reference Elwyn, Edwards and EcclesElwyn 2001). Using such a method, choice is determined by an algorithmic procedure, whereby the utility of each possible choice is calculated arithmetically using the formula:

utility = probability of outcome × value of outcome.

BOX 1 Intuition and reason in decision-making

Intuition

-

• Fast

-

• Effortful

-

• May be emotionally charged

-

• Opaque

Reason

-

• Slow

-

• Effortless

-

• Emotionally neutral

-

• Transparent

Positive and negative values can be incorporated into the formula to reflect benefits and harms respectively. Ultimately, an option of highest utility is calculated, which then dictates the appropriate choice.

There is ample evidence, however, that this is not how everyday dilemmas are managed (Reference PlousPlous 1993). Such a bald mathematical approach in any case is of limited practical use to psychiatrists making decisions where the competing variables may be incommensurate and/or difficult to quantify. How, for example, to fairly weigh the relative value of dignity against the possibility of self-harm (Reference BellBell 1999)? Although numerical values could be applied to such concepts, this raises the question of how to decide on such numbers.

Limitations on conscious processing power and on time available to busy clinicians also make the arithmetical netting-out of costs and benefits unrealistic in everyday psychiatric practice (Reference FaustFaust 1986; Reference Elwyn, Edwards and EcclesElwyn 2001).

If this rational approach is not feasible, should psychiatrists simply resort to trusting unfettered intuition when making high-risk decisions? Doing what feels right generally works in our daily life: stopping at a red light is a learned habit that does not require careful conscious weighing up of pros and cons. The neuropsychological system responsible for such automatic choices (Reference KahnemanKahneman 2003) is fast and effortless, based on habits derived from hard-wired dispositions or from cognitive associations that have been learned over time. This system has an emotional aspect: particular autonomic physiological changes are associated with intuitive choices (Reference Bechara, Damasio and TranelBechara 1997), the basis of the so-called ‘gut feeling’.

Although they contrast with the ‘rational’ system, it would be a mistake to consider intuitive choices as ‘irrational’; they have considerable adaptive value and make sense in many circumstances (Reference GigerenzerGigerenzer 2007). However, just as the human visual system has inbuilt ‘rules of thumb’ (such as ‘small things are far away’), which can mislead and lead to optical illusions, so it is with the intuitive decision-making system. Although it may serve us well most of the time, intuitive decision-making carries with it the inevitability of certain ‘heuristic biases’,Footnote † which, if left unchecked by conscious deliberation, may unwittingly lead to departures from fair, balanced and appropriate decision-making (Reference PlousPlous 1993). Just as with optical illusions, which persist even when the ‘trick’ is known, such biases may continue to affect what we ‘feel’ is the optimal choice even after their presence is made explicit (Reference FineFine 2006). They are more common when the cognitive system is operating near to its limits, that is, when it is under the stress of considering complex, demanding problems (Reference FineFine 2006; Reference MontagueMontague 2006).

In a diversity of fields, even experienced experts relying purely on intuitive judgement often fail to perform as well as more systematic, mechanical decision-making systems (Reference Dawes, Faust and MeehlDawes 1989). Research into assessing the likelihood of future violence in people with mental disorders is consistent with this and generally finds that intuitive unchecked clinical judgement is less accurate than estimates that incorporate systematic consideration of empirically derived risk factors (Reference Webster and HuckerWebster 2007). A major reason for this is likely to be the multiple ways in which heuristic biases can derail intuitive decisions from unbiased optimal decision-making. I will now consider the major classes of such biases and how each may adversely affect particular kinds of risk decision.

Common heuristic biases

Box 2 summarises the common sources of bias. Such biases are not independent: they overlap and/ or interact to some extent, sometimes having a synergistic effect on the likelihood of error.

BOX 2 Potential sources of error and bias

Irrelevant feelings and factors that can influence estimates of likelihood

-

• ‘What I have experienced is more likely’

-

• ‘What I can remember is more likely’

-

• ‘What I can easily imagine is more likely’

-

• ‘What I want is more likely’

-

• ‘What I expect is more likely’ (confirmation bias and illusory correlations between phenomena)

-

• Hindsight bias

Relevant factors (often ignored) related to the likelihood of possible outcomes

-

• Base-rate data

-

• Contextual influences

Social influences

-

• Cognitive dissonance

-

• Groupthink

Heeding irrelevant factors

Faced with any dilemma, a critical variable in determining the appropriate choice is the relative likelihoods of the potential outcomes linked with each possible choice. Unfortunately, clinicians, like most people, often struggle with probabilistic thinking (Reference GigerenzerGigerenzer 2002) and errors are common at this stage. Various factors that have no empirical relevance to the issue may exert an influence. The question ‘How likely is this outcome?’ may be inadvertently replaced by ‘How accessible is this outcome?’, where ‘accessible’ refers to how easily the decision-maker can mentally represent the outcome (Reference KahnemanKahneman 2003). Although this ‘availability heuristic’ may serve us well in many mundane, everyday tasks (Reference GigerenzerGigerenzer 2007), it is likely to mislead, sometimes grossly, in a clinical context. Various factors affect the ease of mental representation, as discussed below.

‘What I have experienced is more likely’

This patient is just like that man I treated last year who ended up killing his father. He must have a very high risk of violence…

Personal experience, even of seasoned clinicians, provides a limited glimpse of possible outcomes. A tendency to privilege anecdotal personal experience may contribute to the poor correlation between experience and quality of judgement (Reference Ruscio, Lilienfeld and O'DonohueRuscio 2007). The problem is exacerbated by the fact that random samples (such as the sample of patients treated by any specific clinician) do not necessarily resemble in every detail the population from which they are drawn. Hence, basing the likelihood, for example, of suicide on idiosyncratic risk factors derived from one's own clinical cases may mislead. Evidence-based medicine, which in its more mature forms can integrate valuable elements of clinical experience (Reference GreenhalghGreenhalgh 2006), is predicated on discouraging clinicians from being misled by this bias.

‘What I can remember is more likely’

We have had three patients abscond in the past 6 months; this man seems likely to abscond if we let him out without an escort…

A recent dramatic incident or ‘bad run’ of adverse outcomes can mislead with respect to likelihood. Recent events are more accessible to memory than more distant (and possibly more prevalent) experiences and so may act as an arbitrary ‘anchor’, biasing estimates of probability of another such event.

‘What I can easily imagine is more likely’

More detailed and/or vivid presentation of information can unduly influence estimates of the significance of information even when the data are no different. For example, when presented with hypothetical scenarios, clinicians are more likely to indicate that they would deny discharge to a patient when the patient's violence risk is communicated in a frequency format (‘20 out of 100 patients’) compared with a probability format (‘20% likely’), possibly because it is easier to visualise frequencies than probabilities (Reference Slovic, Monahan and MacGregorSlovic 2000).

Similarly, as most politicians recognise, a small number of individual testimonials may overshadow the impact of statistical data. Dramatic episodes such as a heinous crime by a psychiatric patient can thus have a disproportionate influence on policy decisions.

‘What I want is more likely’

A key rationale for separating the role of forensic evaluator from that of treating clinician is that it is very difficult to avoid the possible impact of wishful thinking on the clinician's estimate of likelihood of bad outcomes (Reference Weinstock, Gold, Simon and GoldWeinstock 2004). Psychiatrists do not want their patients to behave violently and so they may underestimate the likelihood of this. Such effects are well recognised in social psychology (Reference PlousPlous 1993). Conversely, the ‘Pollyanna effect’ (Reference Boucher and OsgoodBoucher 1969), whereby the more desirable elements of an outcome may be emphasised because that outcome is likely, can also derail optimal judgement.

‘What I expect is more likely’ (confirmation bias)

He seemed very pleasant, so I didn't ask him about plans to harm other people…

It is usual for diagnostic (and prognostic) hypotheses to be formed very early in a clinical assessment (Reference GroopmanGroopman 2007). Early estimates formed in a clinician's mind regarding risk in a given patient may have some basis in evidence: angry people are more likely to harbour violent plans and depressed people are more likely to have suicidal ideation. Indeed, the value of empirical risk factors lies in their capacity to tell us something about the probability of a particular phenomenon given their presence.

However, the presence of a given risk factor is rarely, if ever, conclusive. Derailment from optimal judgement (with regard, for example, to diagnosis or risk) can thus occur if we follow our tendency to look only for ‘affirmatives’ – for further evidence to confirm our initial hypothesis. Hence, there is value in seeking exclusionary diagnostic signs, such as enquiring about warm interpersonal ties in a patient believed to be schizoidal (Reference FaustFaust 1986).

The related tendency to see illusory correlations between phenomena is the basis for superstitious thinking and, at times, dangerous medicine. Exclusive focus on cases where treatment has coincided with recovery has led to persistence with ineffective or even deadly treatments. The actual strength of a relationship between two variables can of course be ascertained only by also considering the proportion of instances in which the variables do not covary.

Hindsight bias

Hindsight bias, whereby it seems obvious in hindsight that a particular outcome was going to occur, has a similar foundation. For example, clinicians may recall after an adverse incident (such as a suicide) that they had experienced a ‘gut feeling’ about the case and regret not taking heed of it. This ignores the fact that the usefulness of such an indicator depends not merely on the frequency of affirmative instances (in which the ‘gut feeling’ indicator was followed by a suicide) but also on the frequency of instances when no such outcome occurred despite a ‘gut feeling’, and also on a consideration of how common the outcome is when no such indicator is present.

Ignoring relevant factors

Unstructured intuitive judgement also tends to ignore various factors that could assist with improving accuracy when estimating relative probabilities of particular outcomes.

Base-rate data

The tendency of clinicians to ignore base rates of violence in the population from which samples have been drawn has long been recognised as a source of error in the field of violence risk assessment (Reference MonahanMonahan 1984; Reference Dawes, Faust and MeehlDawes 1989). Precisely how much heed mental health clinicians should pay to population-based risk factors continues to be debated, particularly with respect to violence and sexual offence risk assessment (Reference Hart, Michie and CookeHart 2007). In general, however, clinicians are well advised to at least consider the prior probability of particular outcomes based on actuarial predictors derived from group data – sometimes termed ‘risk status’ (Reference Douglas and SkeemDouglas 2005) – and to use such information to anchor their estimates of likelihood of a given outcome after more case-specific information has been considered. For example:

if one is 99% sure that someone with a major depression is not suicidal, but 50% of patients with similar presentations and circumstances make attempts, then one should lower one's confidence, and this will probably move it to a level at which one takes appropriate safeguards. (Reference FaustFaust 1986)

Contextual factors

Neglecting the influence of contextual factors on the likelihood of particular outcomes has long been noted as a source of error in risk assessment (Reference MonahanMonahan 1984). For example, the influence of peers on likelihood of antisocial behaviour may be ignored by many clinicians (Reference Andrews and BontaAndrews 2003). This may be a result of the universal cognitive bias towards underestimating the role of situational factors when considering the determinants of undesirable behaviour by other people (Reference PlousPlous 1993).

Social influences

Although there is only limited evidence regarding their role in mental health, the processes of ‘cognitive dissonance’ and ‘groupthink’ have the potential to derail optimal decision-making, especially if it is being undertaken by groups such as committees or multidisciplinary teams.

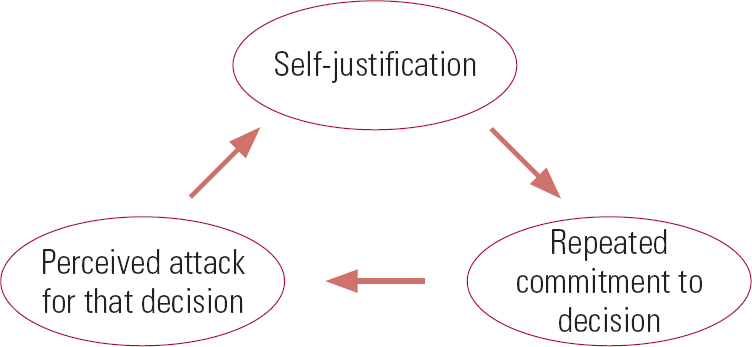

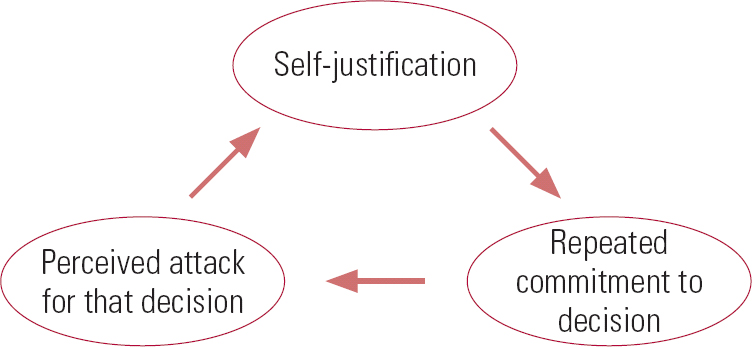

Cognitive dissonance

When confronted with information that is incompatible with a decision or a public commitment that has already been made, people tend to feel discomfort. Cognitive dissonance is the phenomenon whereby subsequent judgements become distorted to better fit with the previous decision and hence diminish the discomfort (Reference Tavris and AronsonTavris 2007) (Fig. 1).

For example, a clinician and their service may have a long-standing public commitment to providing care for people with severe mental illness. Resource and other constraints, however, may make it difficult for them to manage very complex or high-risk cases. A conflict may then occur between the following:

-

• a ‘public commitment to care for needy people’

-

• an ‘inability to care for this needy person’.

The need to resolve dissonance may encourage a subtle reinterpretation of the case: for example, the diagnosis may be modified to something other than severe mental illness (such as a substance use problem) or the level of risk may be downplayed.

Groupthink

Social psychology has amply demonstrated the power of the social rule that implores us not to ‘break ranks’ (Reference PlousPlous 1993; Reference GigerenzerGigerenzer 2007). In teams, this may be manifest as groupthink: a process whereby the members' ‘strivings for unanimity’ override their motivation to realistically appraise different courses of action (Reference JanisJanis 1982). It is especially likely within cohesive, insular groups, with a strong sense of their own inherent morality in which dissent is discouraged. Even prolonged discussion within such groups may simply amplify a pre-existing inclination towards caution or risk (Reference Hillson and Murray-WebsterHillson 2005), regardless of whether such a shift is warranted.

Optimal decision-making

Although formalised arithmetical computation of ‘expected utilities’ is an unrealistic model for clinical risk decision-making, unconstrained reliance purely on what intuitively ‘feels right’ will clearly encourage biases and inconsistencies. Theoretical developments (Reference KahnemanKahneman 2003) suggest that intuitive and rational modes of thought can, however, be used in tandem, as complementary rather than antithetical processes. This parallels developments in violence and suicide risk assessment, where ‘structured professional judgement’, utilising the best features of actuarial and clinical approaches, has proven to be both useful and valid (Reference Bouch and MarshallBouch 2005; Reference Webster and HuckerWebster 2007).

In a similar vein, I suggest the following series of steps as a means of constraining and structuring decision-making. They will assist with minimising bias and incompleteness (Reference Abelson, Levi, Lindzey and AronsonAbelson 1985), while still allowing appropriate input to the process from that affectively coloured, intuitively derived data source termed ‘professional judgement’. These steps can be usefully applied to any risk-related decisional process and will help to make the basis for a decision that is transparent and defensible.

Step 1: Optimise the context

Heuristic biases are more likely when the decision-maker feels under time pressure, under demand to perform other cognitive tasks at the same time, or, surprisingly, is in a particularly good mood (Reference KahnemanKahneman 2003). These factors, together with those that may encourage unhelpful social processes, can be minimised by setting up procedural norms for making particularly difficult decisions. Box 3 outlines the suggested norms.

BOX 3 Procedural norms for making particularly difficult decisions

-

• Recognise that quality decision-making in complex situations is a demanding cognitive task and allocate personnel and time resources accordingly

-

• Ensure that the mood and atmosphere of decision-making bodies is reasonably sober and formal

-

• Encourage leaders to permit criticism and dissent from any perceived ‘party line’

-

• For very complex matters, set up several distinct subgroups to consider the same question

-

• Use a devil's advocate approach: systematically consider all realistic options even when the majority is clearly in favour of one over the others

Step 2: Define the question and clarify the goals

Many decisions about risk issues need to incorporate a range of opinions from various stakeholders. A primary step is to clarify:

-

• the question

-

• the goals of the decision

-

• the criteria for success or failure.

Lack of clarity in such matters will encourage a poor process. Commonly, different stakeholders have different ideas as to the nature of the underlying question (Reference Del Mar, Doust and GlasziouDel Mar 2006), the goals of the exercise and/or the relative value of different outcomes. For example, a governmental decision to stop allowing patient leave from a forensic hospital for mentally disordered offenders may eliminate the possibility of absconding. However, it may also increase the likelihood of offenders both relapsing into active mental illness and reoffending after their release. The impact of such reoffending on the governmental department involved is minor compared with the dramatic impact of an absconding from custody, but the impact on the offender and victim is very significant.

Losing sight of ultimate goals and criteria for success may also allow ‘secondary’ risk management (Reference UndrillUndrill 2007) – concerns about organisational reputation – to override considerations that should be primary, such as the well-being of patients. Once the question is clarified, relevant information can be gathered and considered.

Step 3: Gather information

Adequate information, both related to the specific case under consideration and derived from the broader literature, must generally be considered before making a defensible decision. However, there are limits to the amount of information that busy clinicians can be expected to gather and there is also a risk that irrelevant information may make errors more likely (Reference Del Mar, Doust and GlasziouDel Mar 2006). One of the major advantages of structured risk assessment instruments for assessing risk of violence, such as the Historical Clinical Risk Management 20-item (HCR–20) scale (Reference Webster, Douglas and EavesWebster 1997), is that they help clinicians to focus on the relatively small number of relevant factors. Properly marshalled information can optimise estimates with respect to the likelihood and potential consequences of each of the options that need to be considered.

Step 4: Consider other options

By definition, at least two different choices need to be compared. The single most useful technique for avoiding derailment by heuristic biases can be implemented at this step: stop to consider why your initial decision might be wrong, even if you feel confident in it (Reference PlousPlous 1993). That is, consider different perspectives and ask questions that seek to disconfirm rather than confirm your initial ideas. Systematic documentation of this process in the form of a cost–benefit analysis may be both clinically helpful and medico-legally protective. This simply involves considering the particular outcomes (both harmful and beneficial) that may follow from each choice under consideration. For each harm and benefit, consider:

-

• the likelihood of occurrence

-

• the consequences if it occurs

-

• legal issues

-

• ethical issues (Reference Miller, Tabakin and SchimmelMiller 2000).

This process will demonstrate that complex dilemmas always involve trade-offs and value judgements. Rather than attempting to minimise these, it is better to make them explicit. Incorporating the values of the relevant stakeholders, in addition to the ‘facts’ of the matter, does not render the process ‘unscientific’. Rather, such considerations are a necessary part of a humane approach to psychiatric decision-making (Reference Fulford, Bloch, Chodoff and GreenFulford 1999).

Systematically listing the potential harms as well as benefits of one's chosen option also leads to better calibration (estimates of one's own level of accuracy), even if the original favoured choice is not altered by this process (Reference PlousPlous 1993), thus guarding against overconfidence. It can also be useful at this stage to reframe relevant data in various ways. For example, if evidence relating to a particular outcome is presented in a probability format (e.g. ‘there is a 0.01 probability of absconding’), then reframe it as a frequency format (‘of 100 such patients in this position, 1 is likely to abscond’). If propositions have been presented as losses then reframe them as gains (e.g. ‘99 out of 100 such patients will use their periods of leave appropriately’). Differing stakeholder perspectives can also be incorporated into the cost–benefit analysis.

Relevant long-term factors should be incorporated to guard against the common bias towards short-term considerations. For example, longer-term therapeutic concerns should be systematically considered when determining whether to discharge a patient at short-term risk of self-harm (Reference WatsonWatson 2003). Of course, the precise temporal boundaries of concern will vary from case to case: the key is to clarify the relevant time frame as part of the decision question itself.

Step 5: Make the decision

After considering possible interventions, the outcomes that may flow from them, and the relative likelihoods and consequences of such outcomes, a choice finally has to be made between particular options. Ultimately, the decision is indeed made on the basis of ‘what feels right’, but the preceding steps in the process should minimise the likelihood of irrational biases influencing this choice. Whatever path is chosen will be open to criticism, since the chosen option will have associated potential harms and the unchosen option potential benefits. Such criticism is easier to refute if one can demonstrate a high-quality decision-making process.

Note that ‘no intervention’ is a choice in itself and should not necessarily be privileged over active change. Changing nothing often feels more attractive, because the status quo is taken as a reference point and the disadvantages of active change from that point subjectively loom larger than the advantages, particularly when only the short term is considered (Reference KahnemanKahneman 2003). Thus, errors of commission often loom larger than errors of omission and we have an inbuilt tendency to follow the default option and to avoid active change (Reference GigerenzerGigerenzer 2007). ‘Business as usual’, such as in-patients not having access to leave, out-patients continuing to be treated at home, or patients remaining on their current medication regimen, should therefore be considered an active choice in itself, alongside the options that involve more obvious active change.

Step 6: Plan for the worst

Theories of decision-making often imply that it is a ‘one-shot’ process. In practice, this is often not the case in mental health. It can be more helpful to see each decision as a step on a ‘risk path’ (Reference CarsonCarson 1996). For example, high-risk mentally disordered offenders should not be precipitously discharged from hospital: discharge should be the endpoint of a graduated process, starting with escorted leaves. If each step on this risk path is successfully negotiated, greater confidence can be given to the decision to take the next step.

Similarly, it is important to have contingency plans in place for adverse outcomes that may follow any given decision. For example, a decision to treat at home may be reversed if matters deteriorate, and the granting of parole may be cancelled if an offender fails to comply with certain risk management procedures. Such an approach requires a reasonably long-term perspective on decision-making and adequate resources to both monitor and intervene after decisions are made.

Step 7: Learn from the outcome

It is useful for decision-makers to include an estimate of their level of confidence when making a particular decision. Not only will this guard against overconfidence but it will also, in the long term, assist them with developing better calibration with respect to their forecasting skills. Calibration can be improved only if feedback from past decisions is provided. In practice this is often difficult for mental health clinicians because relevant outcome data may be delayed or not readily available. Effective quality assurance processes at the level of a service, and outcomes research more broadly, will assist decision-makers to continually learn from the past.

In the long term, optimising decision-making processes should lead to a healthy preponderance of positive outcomes over negative outcomes. However, it is in the nature of complex dilemmas that negative outcomes cannot totally be avoided. Although high-profile bad outcomes may be avoidable by implementing extremely conservative measures, this may constitute a poor process, resulting in worse overall outcomes from more balanced perspectives that incorporate considerations such as optimising patients' recovery (Reference CarsonCarson 1996).

Conclusions

The tired debate between intuitive/expert and mechanical/actuarial approaches to decision-making has moved on. In mental health, optimal clinical decision-making processes use models that recognise the practical value of intuitive approaches in dealing with complex issues. To avoid being derailed by certain common heuristic biases, however, a certain degree of rational systematic analysis is a necessary adjunct to such approaches. The framework outlined in this article accommodates both rational and intuitive expert modes, with the aim of optimising decision-making in high-risk situations.

MCQs

-

1 The intuitive mode of thinking is:

-

a effortful

-

b slow

-

c emotionally neutral

-

d unbiased

-

e fast.

-

-

2 When assessing for risk of violence in a patient with a mental disorder:

-

a clinical experience is the most reliable guide

-

b using the HCR–20 guarantees an estimate free from bias

-

c actuarial tools are of no practical help to clinicians

-

d ‘structured professional judgement’ has been shown to be a valid approach

-

e contextual variables should be ignored.

-

-

3 Heuristic biases:

-

a can always be avoided by simply being aware of their existence

-

b may lead to suboptimal decisional processes

-

c are always detectable, in hindsight, when a bad outcome occurs

-

d are very unlikely to occur when teams (rather than individuals) make decisions

-

e include the tendency to favour change over the status quo.

-

-

4 Appropriate guidance for optimal decision-making processes does not include:

-

a allowing plenty of time

-

b encouraging a bright and happy mood

-

c having a leader who welcomes dissent and debate

-

d adopting a devil's advocate approach

-

e clarifying goals and values of the relevant stakeholders.

-

-

5 Cost–benefit analysis:

-

a requires that every relevant factor be expressed in numerical terms

-

b should avoid concerns about ethics or legislation

-

c ensures that secondary risk management appropriately takes priority

-

d guarantees an ideal outcome

-

e can assist with both consideration and documentation of the factors involved in making a decision.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | f | a | f | a | f | a | f | a | f |

| b | f | b | f | b | t | b | t | b | f |

| c | f | c | f | c | f | c | f | c | f |

| d | f | d | t | d | f | d | f | d | f |

| e | t | e | f | e | f | e | f | e | t |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.