It is just over 1 year since my appointment as Director of Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for the Royal College of Psychiatrists. I had previously been involved in CPD as CPD Regional Coordinator for the West of Scotland. I have also been a college tutor and clinical director and am currently a course organiser.

When the College first considered CPD, it was against a background of considerable public concern regarding the regulation of doctors working in the National Health Service (NHS). We have come to think of the ‘Bristol case’, concerning the avoidable deaths of children following heart surgery at the Bristol Royal Infirmary, as being the watershed of such concerns (Reference SmithSmith, 1998). Perhaps the view held within the medical profession before Bristol was that there were a few ‘bad apples’ and that CPD might be a formal mechanism that would target such individuals. Following the Bristol case, however, the profession as a whole was ‘implicated’ and public concerns have no longer been centred on the few.

‘Transparency’ became essential. It was no longer good enough for doctors merely to give their word that they were keeping up to date; they also had to demonstrate it. The College developed its CPD policy as a ‘framework that acknowledges and formalises such activity’ (Reference Katona and MorganKatona & Morgan, 1999). One aspect was the completion of an annual return for CPD. Initially, this was viewed as irritating bureaucracy by many who had always regarded CPD (even if they did not call it this) as core to their professional identity. Alongside the irritation factor, there has also been a great deal of anxiety, above all over how CPD links to appraisal and, ultimately, to revalidation.

In this editorial, I describe aspects of our College's CPD policy (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2001) and, in particular, its relation to NHS appraisal and to revalidation.

CPD, appraisal, revalidation and anxiety

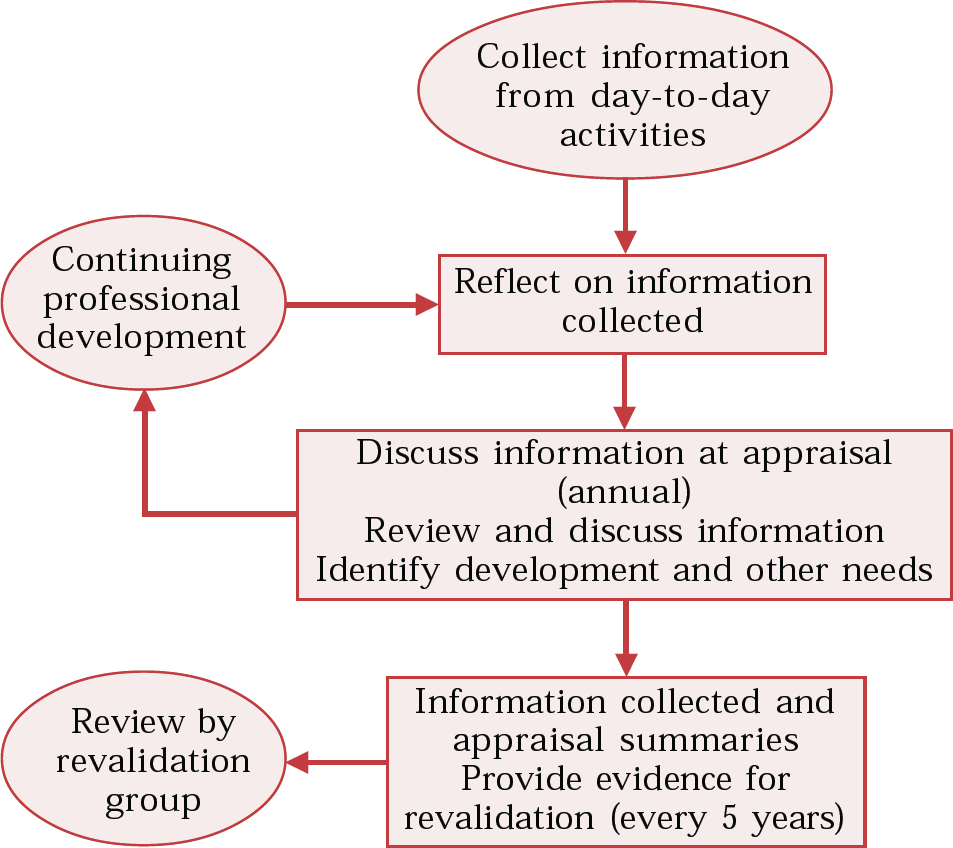

The revalidation procedures of the General Medical Council (GMC), the NHS appraisal process and the Royal College of Psychiatrist's CPD policy have been developed separately but simultaneously. The policies themselves, their context and how their procedures interlink are described by Newby (2003, this issue) and Reference Brown, Parry and OyebodeBrown et al(2003) and are illustrated in Fig. 1.

For many of us, there has been a lack of clear distinction between CPD and NHS appraisal. This has been in terms not only of the territory covered but also of the similarity of language used and procedures employed. Both policies, for example, emphasise the supportive nature of their exercise and both have a personal development plan (PDP) as the main outcome.

This lack of clarity has heightened existing unease. The rhetoric of support has appeared to be out of keeping with the prominence given to under-performance and the ‘bad apples’ of the medical profession. For many, the policies have blurred together and anxieties have ultimately coalesced around concerns regarding future registration.

The focus of NHS appraisal

National Health Service trusts are responsible for ‘appraisal’ as a part of their clinical governance procedures. NHS appraisal is thus an employer-led process that takes, in the first instance, an organisational perspective. Organisations themselves can be viewed as having developmental needs. Key tasks of the NHS include service development, risk management and policy implementation. In order to accomplish these tasks, the NHS depends on the acquisition of specialised training and skills by individuals.

Implementing the NHS appraisal policy is an example of such organisational development. Consultants will be appraised by clinical directors, medical directors or designated senior clinicians. These appraisers need to be trained to carry out an appraisal and such training is therefore a fundamental organisational requirement if the policy is to be implemented.

Does CPD differ from NHS appraisal?

The main features of CPD and of NHS appraisal are compared in Table 1. In common with NHS appraisal, a core aspect of CPD policy is the preparation of a PDP with a number of learning objectives for the coming year (Reference NewbyNewby, 2003). However, for CPD, the individual is the starting point rather than the organisation. Personal learning objectives will take account of our own career development and personal training needs and aspirations in addition to trust and NHS priorities.

In practice there will often not be a clear distinction between individually determined and organisationally driven learning objectives. Preferably these will coincide. There is, however, a kind of tension in the process, and individuals and employers must respect and seek to resolve any differing needs and priorities. Thus, learning objectives will both feed into appraisal and may arise from it (Fig. 1).

How do CPD and appraisal link with revalidation?

Revalidation is the process by which the GMC will determine whether medical practitioners should remain on the Medical Register. Annual NHS appraisal will form the basis of revalidation. CPD will support NHS appraisal. The GMC has made it clear that, although appraisal and revalidation are based largely on the same sources of information, they are two separate processes with different objectives. This is true also of the relationship between CPD and appraisal. All three policies share common elements and in fact are interdependent, yet each one is distinct from the other (Fig.1).

Conclusions

Continuing professional development is a small but important part of the new regulatory framework. In the process of regulation, CPD will be both a mechanism of peer support and a preparation for annual appraisal. It has a distinct focus on the needs of the individual and will therefore be crucial in feeding individual learning objectives (rather than those that are organisationally determined) into appraisal.

Table 1 Comparison of NHS appraisal and CPD

| NHS appraisal | CPD |

|---|---|

| Annual | Minimum twice per year |

| Top-down | Bottom-up |

| Employer-led | Individually led |

| One-to-one | Peer-group-based |

| Organisational focus | Individual/career focus |

| Review of performance | Establishes personal learning needs |

| Leads to revalidation | Prepares for NHS appraisal |

Fig. 1 CPD, appraisal and revalidation (General Medical Council, 2002; redrawn with permission).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.