Delivering cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) for obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) requires a detailed understanding of the phenomenology and the mechanism by which specific cognitive processes and behaviours maintain the symptoms of the disorder. A textbook definition of an obsession is an unwanted intrusive thought, doubt, image or urge that repeatedly enters a person's mind. Obsessions are distressing and ego-dystonic but are acknowledged as originating in the person's mind and as being unreasonable or excessive. A minority are regarded as overvalued ideas (Reference VealeVeale, 2002) and, rarely, delusions. The most common obsessions concern:

-

• the prevention of harm to the self or others resulting from contamination (e.g. dirt, germs, bodily fluids or faeces, dangerous chemicals)

-

• the prevention of harm resulting from making a mistake (e.g. a door not being locked)

-

• intrusive religious or blasphemous thoughts

-

• intrusive sexual thoughts (e.g. of being a paedophile)

-

• intrusive thoughts of violence or aggression (e.g. of stabbing one's baby)

-

• the need for order or symmetry.

A cognitive–behavioural model of OCD begins with the observation that intrusive thoughts, doubts or images are almost universal in the general population and their content is indistinguishable from that of clinical obsessions (Reference Rachman and de SilvaRachman & de Silva, 1978). An example is the urge to push someone onto a railway track. The difference between a normal intrusive thought and an obsessional thought lies both in the meaning that individuals with OCD attach to the occurrence or content of the intrusions and in their response to the thought or image.

Thought–action fusion

An important cognitive process in OCD is the way thoughts or images become fused with reality. This process is called ‘thought–action fusion’ or ‘magical thinking’ (Reference RachmanRachman, 1993). Thus, if a person thinks of harming someone, they think that they will act on the thought or might have acted on it in the past. A related process is ‘moral thought–action fusion’, which is the belief that thinking about a bad action is morally equivalent to doing it. Lastly, there is ‘thought–object fusion’, which is a belief that objects can become contaminated by ‘catching’ memories or other people's experiences (Reference Gwilliam, Wells and Cartwright-HattonGwilliam et al, 2004).

Responsibility

One of the core features of OCD is an overinflated sense of responsibility for harm or its prevention. Responsibility is defined here as: ‘The belief that one has power that is pivotal to bring about or prevent subjectively crucial negative outcomes. These outcomes may be actual, that is having consequences in the real world, and/or at a moral level’ (Reference Salkovskis, Richards and ForresterSalkovskis et al, 1995). The difference in OCD is the individual's appraisal of situations: the belief that harm might occur to the self, a loved one or another vulnerable person through what the individual might do or fail to do. Harm is interpreted in the broadest sense and includes mental suffering; for example, some people with obsessive worries about contamination fear they will go ‘crazy’ or that the anxiety will go on for ever. Individuals with OCD believe they can and should prevent harm from occurring, which leads to compulsions and avoidance behaviours.

Non-specific cognitive biases

People with OCD have a number of other cognitive biases (Box 1) that are not necessarily specific to the disorder but, in combination with cognitive fusion and an inflated sense of responsibility, lead to anxiety and compulsive symptoms. The excessively narrow focusing on monitoring for potential threats (e.g. fear of contamination from blood, resulting in constant checking for red marks), even when no immediate threat is present, means that less attention is focused on real events. This reduces the individual's confidence in their memory, which in turn leads to further checking behaviours. Intrusive thoughts, images or urges are often accompanied by an excessive attentional bias on monitoring them. This leads to a heightened cognitive self-consciousness and an increase in the detection of unwanted intrusive thoughts and worries about not performing a compulsion or safety behaviour.

Box 1 Non-specific cognitive biases

-

• Overestimation of the likelihood that harm will occur

-

• Belief in being more vulnerable to danger

-

• Intolerance of uncertainty, ambiguity and change

-

• The need for control

-

• Excessively narrow focusing of attention to monitor for potential threats

-

• Excessive attentional bias on monitoring intrusive thoughts, images or urges

-

• Reduced attention to real events

Emotion

The dominant emotion in an obsession may be difficult for some patients to articulate but it is commonly anxiety. Some also experience disgust, especially when they think that they could have been in contact with a contaminant. Others feel ashamed and condemn themselves for having intrusive thoughts of, for example, a sexual or aggressive nature, that they believe they should not have. Occasionally, a person with OCD believes that they are responsible for a bad event in the past; in such cases, the main emotion is guilt. Many individuals are also depressed, with various secondary problems caused by the handicap; comorbidity with a mood disorder is relatively common. At times, anger, frustration and irritability are prominent. Because of the range of emotions, it is not surprising that some patients find it difficult to articulate and untangle their dominant emotion.

Compulsions and safety-seeking behaviours

Compulsions are repetitive behaviours or mental acts that a person feels driven to perform. A compulsion can either be overt and observed by others (e.g. checking that a door is locked) or a covert mental act that cannot be observed (e.g. mentally repeating a certain phrase). Covert compulsions are generally more difficult to resist or monitor, as they are ‘portable’ and easier to perform. The term ‘rumination’ covers both the obsession and any accompanying mental compulsions and acts. As with obsessions, there are many types of compulsion (Box 2).

Box 2 The most common compulsions

-

• Checking (e.g. gas taps; reassurance-seeking)

-

• Cleaning/washing

-

• Repeating actions

-

• Mental compulsions (e.g. special words or prayers repeated in a set manner)

-

• Ordering, symmetry or exactness

-

• Hoarding

Early experimental studies established that compulsions, especially cleaning, are reinforcing because they seem to reduce discomfort temporarily. Furthermore they strengthen the belief that, had the compulsion not been carried out, discomfort would have increased and harm may have occurred (or not have been prevented). This increases the urge to perform the compulsion again, and a vicious circle is thus maintained. However, compulsions do not always work by reducing anxiety and are often intermittently reinforcing. Compulsions may function as a means of avoiding discomfort, as in examples of obsessional slowness (Reference VealeVeale, 1993). Compulsions are usually carried out in a relatively stereotyped way or according to idiosyncratically defined rules. The compulsion to hoard refers to the acquisition of and failure to discard possessions that appear to be useless or of limited value, and to cluttering that prevents the appropriate use of living space (Reference Frost and HartlFrost & Hartl, 1996).

The individual's criteria for terminating compulsions are an important factor in their maintenance. Someone without OCD finishes an action such as hand-washing when they can see that their hands are clean; someone with OCD and a fear of contamination finishes not only when they can see that their hands are clean but when they feel ‘comfortable’ or ‘just right’. Others may end a compulsion when they have a perfect memory of an event. These additional criteria for terminating compulsions may cause them to last even longer. Progress in overcoming OCD can be made only when the criteria for terminating a compulsion are restricted to objective criteria.

A ‘safety-seeking behaviour’ is an action taken in a feared situation with the aim of preventing catastrophe and reducing harm (Reference SalkovskisSalkovskis, 1985); it therefore includes compulsions and neutralising behaviours. Neutralising is any voluntary or effortful mental action carried out to prevent or minimise harm and anxiety with the goal of either controlling a thought or changing its meaning to prevent negative consequences from occurring (e.g. visualising that the doctor is telling me that I don't have cancer until I feel relief). Other safety-seeking behaviours include mental activities such as trying to be sure of the accuracy of one's memory, trying to reassure oneself and trying to suppress or distract oneself from unacceptable thoughts. Such behaviours may reduce anxiety in the short term but lead to a paradoxical enhancement of the frequency of the thought in a rebound manner.

Avoidance

Although avoidance is not part of the definition of OCD, it is an integral part of the disorder and is most commonly seen in fears of contamination. An example of avoidance is a woman with a fear of contamination who will not touch toilet seats, door handles or taps used by others. She will hover over the toilet seat, use her elbow to open doors and taps, use rubber gloves to put rubbish in the dustbin, avoid picking up items from the floor, avoid shaking hands with people or touching a substance that looks dangerous to her. Avoidance can also occur mentally: trying not to think or feel something upsetting. Not all situations can be avoided and safety-seeking behaviours are often used within a feared situation.

Linking obsessions, compulsions and avoidance behaviour

The content of obsessions, compulsions and avoidance behaviour in OCD are closely related. For example, when a patient has to touch something that they normally avoid, the compulsive washing starts. When avoidance is high, the frequency of compulsions may be low, and vice versa. If a woman's obsession is of stabbing her baby, she might avoid being alone with him or put all knives or sharp objects out of sight, ‘just in case’. If this fails to reduce her obsession, she may ensure that someone is with her all the time (a safety-seeking behaviour) or try to neutralise the thought in her head. These acts in turn increase her doubts and prevent her from disconfirming her fears, and the cycle continues.

Assessment

Clinical assessment of OCD is summarised in Box 3. The assessment of avoidance requires a rating of predicted distress, so that a hierarchy of avoided situations without safety-seeking behaviours may be identified for therapy, together with an understanding of how the avoidance interacts with the obsessions and the distress experienced. Some patients also try to avoid ideas, thoughts or images by distraction or attempts to suppress them.

Box 3 Areas to cover in clinical assessment

-

• The context in which OCD has developed

-

• The nature of the obsession(s): their content; the degree of insight; the frequency of their occurrence; the triggers; the feared consequence (What is the worst thing that can happen?); the patient's appraisal of the obsession (What did having the intrusive thought mean to you? What sense did you make of it? Could harm occur as a result of this? What would happen if you could not get rid of the intrusions?)

-

• The main emotion(s) linked with the obsession or intrusion

-

• The compulsion(s) and neutralising: what the person does in response to the obsession; a rating of predicted distress if the compulsion is resisted; the feared consequences of resisting it; their experience of trying to stop a compulsion; the criteria used for terminating the compulsion and the assumptions held if they stopped using a compulsion. Indirect assessment might include activities such as the number of rolls of toilet paper or bars of soap used per week

-

• The avoidance behaviour: all the situations, activities or thoughts avoided are listed and rated on a scale (e.g. 0–100 in standard units of distress), according to how much distress the person anticipates if they experience the thought or situation without a safety-seeking behaviour

-

• The degree of family involvement

-

• The degree of handicap in the person's occupational, social and family life

-

• Goals and valued directions in life

-

• Readiness to change and expectations of therapy, including previous experience of CBT for the disorder

The patient's problems, goals in therapy and valued directions (e.g. to be a good parent and partner) should be clearly defined. Progress should be rated on standard outcome scales at regular intervals. The standard observer-rated tool is the Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (Reference Goodman, Price and RasmussenGoodman et al, 1989). The Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory (Reference Foa, Kozak and SalkovskisFoa et al, 1998) is a standard subjectively rated scale. Patients are usually offered time-limited CBT for between 6 and 20 sessions, depending on the severity and chronicity of the problem. Patients with more severe OCD may require a more intensive programme in a residential unit or in their home.

Family involvement

Some families accommodate an individual's avoidance and compulsions; some are overprotective, aggressive or sarcastic; they may minimise the problem or avoid the individual as much as possible. Sometimes the behaviours associated with the OCD restrict the activities of family members (such as gaining access to the bathroom) or their freedom to use certain rooms in the home because of hoarding. People with OCD may react with aggression when their compulsions are not adhered to by their family. Frequently, family members have different coping mechanisms, leading to further discord when they disagree over the best way of dealing with the situation. Assessment should focus on how different members of the family cope and their attitudes to treatment. The goals of CBT include helping family members to be consistent and emotionally supportive, without accommodating the OCD. They may be encouraged to assist in exposure tasks and behavioural experiments if these would facilitate recovery from OCD.

OCD in children and adolescents

Chronic, severe OCD can be particularly disabling in young people, who often have little insight into their condition and are not ready to change. Using the Mental Health Act is usually unhelpful unless for a trial of medication, for reasons of physical health or because there is a need to remove the patient from their family and home environment. It is preferable to try to engage young patients in understanding the cognitive–behavioural model of OCD and to help them follow their valued directions in life despite the disorder. If the OCD is so severe that it prevents the individual from coping without supervision, the parents may make their child homeless and ask for the child to be rehoused, as this may motivate the individual to change.

Exposure and response prevention

Behavioural therapy for OCD is based on learning theory. This posits that obsessions have, through conditioning, become associated with anxiety. Various avoidance behaviours and compulsions prevent the extinction of this anxiety. This theory of the disorder has led to ‘exposure and response prevention’, in which the person is exposed to stimuli that provoke their obsession and then helped not to react with escape and compulsions; repetition of these stages leads to extinction of the feared response. Exposure and response prevention remains a good evidence-based treatment for OCD (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2005).

The treatment method

First, a functional analysis is conducted and a hierarchy of the patient's feared situations and thoughts is generated. Graded exposure follows, beginning with the stimuli that are the least anxiety-provoking. The rationale of habituation is explained to the patient: repeated self-exposure to feared stimuli will lead to extinction. Response prevention involves instructing the patient to resist the urge to carry out a particular compulsion and wait for the ensuing anxiety to subside. Patients are never forced to stop a compulsion, but the therapist may act as a model for exposure and response prevention and gently encourage the patient to follow. Compulsions may be reduced gradually or patients instructed to delay their compulsive response for as long as possible. A patient unable to resist a compulsion to wash their hands would be asked to re-expose themselves to the feared stimuli – for example recontaminating themselves by touching a toilet seat and thus negating the effect of the compulsion.

Therapist-supervised exposure is generally more effective than exposure and response prevention practised alone by the patient as homework assignments. However, it is essential that the involvement of the therapist fades over time, with the patient taking responsibility for their progress. Prolonged (90 minute) exposure sessions held several times weekly with frequent homework will result in greater symptom reduction. Combining actual and imagined exposure is superior to actual exposure alone.

Outcome with exposure and response prevention

About 25% of patients refuse or drop out from exposure and response prevention, and of those that adhere to the therapy about 75% improve (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2005). Poor prognosis is associated with comorbidity (particularly depression or schizotypal personality); severe avoidance; overvalued ideation; expressed hostility from family members; and hoarding.

Adding cognitive therapy

Adding cognitive therapy to exposure and response prevention includes many of the same procedures, but they are presented as behavioural experiments to test out specific predictions. The emphasis is still on behavioural change and following valued directions in life. It attempts to improve engagement and provide a formulation that helps the patient to identify a broader range of cognitive processes (e.g. inflated responsibility and thought–action fusion) that maintain symptoms of OCD. The approach is to question these processes and the patient's appraisals of their intrusive thoughts and urges (not the content).

Cognitive–behavioural therapy has now been found to be superior to exposure and response prevention (P. M. Salkovskis, personal communication, 2007).

Normalising intrusive thoughts and urges

The initial strategy in CBT is to normalise the occurrence of intrusions and to emphasise that they are irrelevant to further action. The patient might be presented with a long list of intrusive thoughts and urges drawn from a community sample or examples that the therapist has personally experienced. Therapist and patient would then discuss the similarities of intrusive thoughts between people with OCD and people without – that is, the content of the thoughts does not differ but the degree of distress, effort and duration does. Patients learn that intrusive thoughts and urges are part of the human condition and are necessary for problem-solving and thinking creatively. Therapy therefore seeks to modify the way the individual interprets the occurrence and/or content of their intrusions, as part of a process of reaching an alternative, less threatening view of intrusive thoughts. The conclusion to be drawn is that the problem lies not with the intrusions but with the meaning that the individual attaches to those thoughts and the various strategies that they adopt to try to control or suppress them. Patients learn that their current strategies increase rather than control the frequency of intrusive thoughts, their levels of distress and the urge to neutralise their thoughts.

Therapy in practice

The formulation

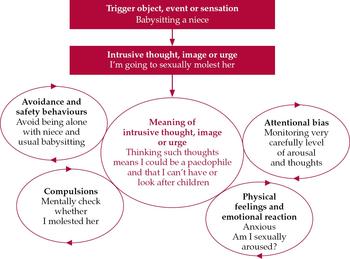

Take the example of Ella, a woman with OCD who has intrusive thoughts of molesting a child. Her therapist would draw up a formulation of the factors maintaining the symptoms and would share it with her (Fig. 1). Engagement may be assisted by a Socratic dialogue and setting up two competing theories to be tested out (Reference Clark, Salkovskis and HackmannClark et al, 1998). The therapist's side of such an interaction is outlined in Box 4. In this example, Ella was able to predict that if theory A were true and she really were a paedophile, then she would be feeling excited at the prospect of babysitting. If, however, theory B were true then she might be feeling very worried and frightened about abusing her niece. The treatment strategy should be to reduce such worries (not to reduce the risk to a child), which were interfering with her ability to be a good aunt and wish to become a mother.

Fig. 1 A formulation in obsessive–compulsive disorder.

Box 4 How does Ella prove to herself that her problem is worrying that she is a paedophile?

Therapist: ‘I want to see if we can build a better understanding of what your problem is and therefore how to solve it. It seems to me there are two explanations to test out. The first explanation, which I will call theory A, is the one you have been using for the past few years, that is, the problem is that you are a paedophile. Theory B, which we would like to test out in therapy, is that you are extremely worried about being a paedophile and in your values care very deeply about children.

Have you noticed that treating it as theory A makes the worry and distress about being a paedophile worse?

Have you ever tried to deal with the problem as if was a worry problem?

Would you be prepared to act as if it was theory B for at least 3 months and then review your progress? You can always go back to treating it as a paedophile problem if it's not working. This will mean gradually dropping all your safety and avoidance behaviours.’

Identifying cognitive processes

The therapist would discuss with Ella the process of cognitive fusion, her overinflated sense of responsibility and other beliefs about her intrusive thoughts or urges. She would be helped to differentiate between thoughts and actions with intention. This might involve behavioural experiments to test out theory B and being alone with children. This is akin to traditional ‘exposure’, but because of the detailed discussion and experiments on the nature of intrusive thoughts, it may be more acceptable and less distressing than just ‘facing your fears’. The cognitive– behavioural model is presented in some detail and referred to throughout treatment – the aim for the patient is not that she stops having intrusive thoughts but that she alters her relationship with her thoughts and develops an understanding of why some strategies increase or decrease her symptoms. Further discussion would focus on the assumptions involved in her appraisals of her thoughts (e.g. the therapist might question the mechanism of how thinking can make an event happen and question the validity of an intrusive thought and how it can reflect an actual event). This may lead to a mental experiment of trying deliberately to induce bad actions or events (e.g. having thoughts of causing the therapist to have a serious accident before the next appointment or having thoughts of harming the therapist while holding a knife against his or her neck).

Safety behaviours and compulsions

The therapist might conduct a functional analysis of the unintended consequences of Ella's avoidance, safety behaviours and compulsions and how they prevent disconfirmation of her worries. Patients tend to believe that their distress and worry will continue unless they carry out their safety behaviours or compulsions. This can be tested out in a behavioural experiment by asking the patient deliberately to perform one of their less disturbing obsessions. For example Mark, a man with OCD who fears being contaminated by HIV (see below), might be encouraged to perform his compulsion (e.g. checking and reassurance-seeking) on one day and on the next to resist the urge, on each occasion monitoring the degree of his distress or worry and the effect on his confidence in his memory. He would then be asked to compare the two experiences. Another experiment might involve the paradoxical effect of thought suppression on the frequency of the intrusive thoughts. This may lead to an experiment that involves asking the patient to record the frequency of a neutral thought under two conditions, with and without thought suppression. This may later be extended to their own intrusive thought. Behavioural experiments may appear to be the same as exposure but with a rationale of testing out certain beliefs about safety behaviours and making predictions about what would happen were they not performed.

Distancing

An important strategy is to help the patient distance themselves from their thoughts or urges and to cease to engage in (‘buy into’) them. A metaphor for thoughts and urges are cars on a road. If one engages with the cars (thoughts) then one might stand in the road and try to divert them (and get run over) or try to get into a car and park it. However, even when one has managed to divert or to park one car there are always more cars to be dealt with. The key is to acknowledge the thoughts (and thank one's mind for its contribution to one's mental health), but not to attempt to stop them or to control them. The goal is to embrace intrusive thoughts and urges, to walk along the side of the road, and to engage with life. This means always experiencing traffic noise in the background – intrusive thoughts never go away and reflect a person's worries. If a patient struggles with distancing themselves from their intrusive thoughts, this may be linked to beliefs about the consequences of not responding to them (e.g. a person who fears being contaminated may believe that they would lose control and go mad). In general, patients are taught to notice and experience their thoughts and feelings without trying to evaluate them or trying to avoid or control them.

Beliefs about contamination

Thought–object fusion (described above) can be used to enhance exposure to contamination. For example, a person can put the tiniest drop of a contaminant (e.g. urine, saliva, semen) into a large volume of water, so that the water has ‘thoughts’ of contamination. The solution can then be transferred to a hand-held spray with which they can ‘contaminate’ themselves or possessions for which they are responsible. This may lead them to question the process of thought–object fusion, and the usefulness of excessive washing or cleaning and any specific predictions that they had made beforehand.

Beliefs about intolerability of uncertainty

The need for certainty is a common theme in OCD, especially for events in the distant future that are impossible to disprove. For example Mark, the man with OCD mentioned earlier, demands to know for certain whether he is HIV positive, despite repeated reassurance from negative tests or positive explanations for his symptoms. Such patients always have a nagging doubt – the blood sample could have been accidentally switched, there could be a new type of HIV which has not yet been discovered, the sero-conversion has not yet occurred and so on. Mark is demanding a 100% guarantee or absolute certainty, which is of course impossible. However, while he continues to believe that he has to be 100% certain, he will focus on the possible doubts. Obviously the feared situations are possible, but they are highly improbable. It is important not to get involved in a detailed analysis of probabilities but to help the patient to focus on the process and recognise the link between the demand for certainty and their distress and further doubt. This will help them to step back and focus on the much higher likelihood of a poor quality of life if they continue to seek reassurance. Patients can be helped to tackle their beliefs using humour: we can guarantee two things in life – death and taxes! A third guarantee is that while the patient continues to demand a guarantee that a feared consequence will not occur they will continue to disturb themselves with their symptoms.

Beliefs about terminating compulsive behaviours

As has already been noted, people with OCD tend to use problematic criteria such as being ‘comfortable’, ‘just right’ or ‘totally sure’ to terminate a compulsion. Patients can be taught that they are diverting increasing amounts of attention and trying too hard to determine the indeterminable (e.g. whether one can be totally sure everything has been done to make something clean). Patients who check their memory have special difficulty. They are demanding to have a perfect or totally clear picture of everything they have done, in the order that it happened. Socratic questioning can be used to illustrate the impossibility of this demand and how each check creates further ambiguous data and more scope for doubt. The criterion of ‘feeling comfortable’ is particularly impossible to achieve when confronting disturbing fears about the harm that one may cause. In this case, patients should be helped to focus their attention away from their subjective feelings and towards the external world (e.g. what they can see with their eyes or feel with their hands). Alternatively, patients may be shown that demanding to feel comfortable or confident before they can terminate a compulsion or confront a fear is akin to putting the cart before the horse. Patients usually need to do tasks uncomfortably and unconfidently before they can achieve comfort and confidence in doing them.

Hazards of cognitive therapy in OCD

A hazard of cognitive therapy in inexperienced hands is that the therapist becomes engaged in subtle requests for reassurance and arguments about minor probabilities. In such cases, it is especially important to use Socratic dialogue to help the patient generate the information needed by a behavioural experiment, or to ask the patient how a colleague or relative would think or act. Most problems in CBT for OCD stem from two failures: challenging the content of intrusive thoughts rather than the patient's appraisal of them or the cognitive process; and not spending enough time on exposure and behavioural experiments. Always relate requests for reassurance or more information to the patient's formulation and the cognitive–behavioural model of OCD, with an emphasis on the effect of various cognitive processes and behaviours.

Key good practice points for using CBT are summarised in Box 5 and further reading is suggested in Box 6.

Box 5 Good practice points in CBT for OCD

-

• Patients should have clearly defined problems and goals for therapy

-

• There should be a shared formulation of the problem that provides a neutral explanation of the symptoms and of how trying to avoid and control intrusive thoughts and urges maintains the patient's distress and disability

-

• Do not become engaged in the content of obsessions and requests for reassurance, and do not argue about the likelihood of a bad event happening – help patients to use their formulation and the cognitive–behavioural model of OCD, and use a Socratic dialogue to focus on the process and consequences of their actions

-

• Do not give up using exposure and response prevention: integrate it with the cognitive approach in the form of behavioural experiments to make predictions

-

• Ensure that patients do not incorporate new appraisals or self-reassurance as another compulsion or way of neutralising

Box 6 Further reading

-

• Antony, M. M., Purdon, C. & Summerfeldt, L. J. (eds) (2007) Psychological Treatment of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder: Fundamentals and Beyond. American Psychological Association.

-

• Salkovskis, P. M. & Kirk, J. (2007) Obsessional disorders. In Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Psychiatric Problems: A Practical Guide (eds K. Hawton, P. M. Salkovskis, J. Kirk, et al), pp. 129–168. Oxford University Press.

-

• Veale, D. & Willson, R. (2005) Overcoming Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: A Self‐Help Guide Using Cognitive Behavioral Techniques. Constable & Robinson.

-

• Wells, A. (2000) Emotional Disorders and Metacognition, pp. 179–199. John Wiley & Sons.

Declaration of interest

None.

MCQs

-

1 Neutralising an intrusive thought or image:

-

a leads to an immediate increase in anxiety

-

b is an involuntary strategy adopted by the patient

-

c aims to create more harm

-

d prevents disconfirmation of the intrusive thought

-

e is identical to a compulsion.

-

-

2 Cognitive processes in OCD include:

-

a thought–action dissociation

-

b tolerance of uncertainty

-

c overinflated sense of responsibility for harm

-

d finishing washing ritual when seeing that one's hands are clean

-

e underestimation of the likelihood of harm.

-

-

3 Compulsions in OCD:

-

a can lead to psychosis if resisted

-

b may initially function as a means of avoiding anxiety

-

c can be resisted by focusing attention inwards on subjective feelings and not by external information

-

d are entirely voluntary

-

e cannot be mental acts.

-

-

4 Unwanted intrusive thoughts and images:

-

a are indistinguishable in content between people with OCD and the ‘normal’ population

-

b can be suppressed in the long term

-

c do not differ in the meaning that people with OCD attach to their occurrence and/or content compared with the ‘normal’ population

-

d are unnecessary for thinking creatively and problem-solving

-

e are rare in the general population.

-

-

5 Assessment for cognitive–behavioural therapy in OCD:

-

a does not require knowledge of the degree of family involvement

-

b does not require knowledge of the patient's degree of insight or overvalued ideation

-

c requires forensic assessment of intrusive thoughts and urges

-

d requires assessment of the patient's readiness to change

-

e requires analysis of countertransference.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | F | a | T | a | F |

| b | F | b | F | b | T | b | F | b | F |

| c | F | c | T | c | F | c | F | c | F |

| d | T | d | F | d | F | d | F | d | T |

| e | F | e | F | e | F | e | F | e | F |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.