Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an auto-immune disorder mediated by the immune-complex and characterised by its protean clinical manifestation and multisystemic involvement (Reference Mak, Mok and ChuMak 2007a). Neuropsychiatric manifestation of SLE (NPSLE) is one of the major and most damaging presentations. It comprises a wide range of neurological syndromes affecting the central, peripheral and autonomic nervous systems, as well as psychiatric syndromes. In view of the diverse clinical manifestation of NPSLE, the American College of Rheumatology research committee devised a nomenclature which gives case definitions for 19 neuropsychiatric syndromes in SLE (ACR Ad Hoc Committee on Neuropsychiatric Lupus Nomenclature 1999) (Box 1). Albeit comprehensive, none of the syndromes described are specific to SLE and, in fact, non-SLE causes such as complications of lupus therapy, infection of the central nervous system (CNS), metabolic dysfunction and drug intoxication may contribute to them. Hence, these complications must be excluded before being ascribed to the underlying immunopathogenic mechanisms (Reference Mak, Chan and YehMak 2007b).

BOX 1 Neuropsychiatric manifestations of SLEFootnote a and prevalence ratesFootnote b

Central nervous system

-

• Aseptic meningitis

-

• Cerebrovascular disease

-

• Demyelinating syndrome

-

• Headache (including migraine and benign intracranial hypertension)

-

• Movement disorder (chorea)

-

• Myelopathy

-

• Seizure disorders

-

• Acute confusional state (<1%)

-

• Anxiety disorder

-

• Cognitive dysfunction (55–80%)

-

• Mood disorder (14–57%)

-

• Psychosis (0–8%)

Peripheral nervous system

-

• Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (Guillain–Barré syndrome)

-

• Autonomic disorder

-

• Mononeuropathy (single/multiplex)

-

• Myasthenia gravis

-

• Cranial neuropathy

-

• Plexopathy

-

• Polyneuropathy

Although overt psychiatric symptoms are often clinically obvious, subtle changes such as mild cognitive impairment are often left unnoticed. This underscores the need for careful and robust clinical assessment tools which help identify these clinically important psychopathologies. In addition, how psychiatrists formally diagnose and evaluate a wide variety of lupus-related psychiatric syndromes and their impacts by using validated assessment instruments and ultimately manage these syndromes in conjunction with rheumatologists needs to be addressed.

This article reviews the immunopathogenesis, clinical manifestation and therapeutic options for NPSLE, and highlights the indispensable role of psychiatrists working with rheumatologists in the collaborative management of these conditions.

Epidemiology, pathogenesis and therapeutic options

Epidemiology

Neuropsychiatric manifestations in people with SLE are fairly common, with a prevalence of 17–75%. The wide range reflects possible inter-ethnic variations of lupus manifestation and different criteria for diagnosis (Reference Stojanovich, Zandman-Goddard and PavlovichStojanovich 2007). Neuropsychiatric manifestations of SLE are complex:

-

• they can occur at any time during the course of the disorder or even precede its onset

-

• they can occur during the active or quiescent phase of lupus

-

• patients may present with single or multiple neurological and/or psychiatric manifestations (Reference Hanly and HarrisonHanly 2005).

Pathogenesis

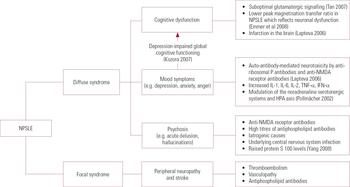

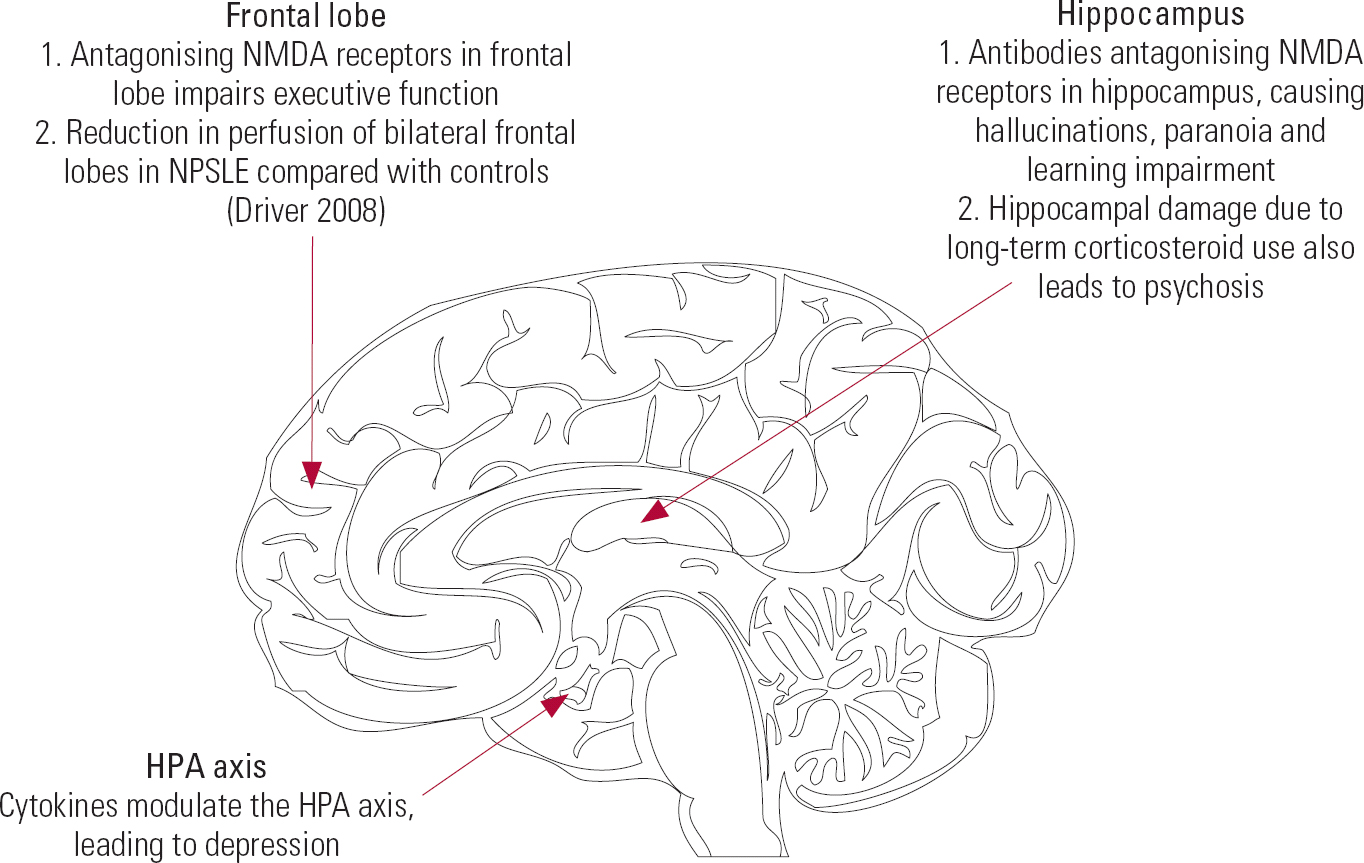

Regarding the nomenclature of NPSLE, clinical manifestation is divided into diffuse and focal syndromes, largely depending on the anatomical sites of the CNS pathology (Fig. 1). Several immunopathogenic mechanisms giving rise to NPSLE syndromes have been proposed. Although NPSLE syndromes such as stroke and peripheral neuropathy are likely to be related to thromboembolism and vasculopathy, the mechanisms for diffuse psychiatric syndromes such as depression and psychosis are related to auto-antibody-mediated neurotoxicity. Among patients with lupus, anti-ribosomal P antibodies are higher in individuals who have depression and/or psychosis than in those who do not (Reference Arnett, Reveille and MoutsopoulosArnett 1996). Anti-n-methyl-d-aspartate (anti-NMDA) receptor antibodies have attracted substantial attention, as NMDA receptors are capable of binding to the neurotransmitter glutamate. The hippocampus expresses the highest number of NR2 NMDA receptors and studies have demonstrated that antagonising NMDA receptors can cause hallucinations and paranoia (Reference Jentsch and RothJentsch 1999). The exact reason why anti-NMDA receptor antibodies can lead to such diffuse NPSLE syndromes is not clear, although antagonisation of NR2 receptors has been shown to induce apoptosis of neurons and subsequent neuronal injury in a way reminiscent of excitatory amino-acid toxicity (Reference Lipton and RosenbergLipton 1994).

FIG 1 Diffuse and focal syndromes in neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (NPSLE) and underlying pathologies. HPA, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; NMDA, n-methyl-d-aspartate; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Antiphospholipid antibodies are associated with focal neurological manifestations such as cerebro-vascular diseases (Reference PetriPetri 2007). Box 2 summarises the auto-antibodies involved in NPSLE.

BOX 2 Auto-antibodies involved in NPSLE

-

• Anti-ribosomal P antibodies

-

• NMDA receptor antibodies

-

• Antiphospholipid antibodies

-

• A proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL) for B cell survival and function (Reference George-Chandy, Trysberg and ErikssonGeorge-Chandy 2008)

-

• Antihistone antibodies (Reference Sun, Shi and HanSun 2008)

Several lines of evidence have demonstrated that serum pro-inflammatory cytokines are involved in depression in SLE. For example, patients with SLE and depression have elevated serum levels of interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-2, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interferon (IFN)-α (Reference Maes, Meltzer and BosmansMaes 1995). Figure 2 summarises the roles of antibodies and cytokines in major neuropsychiatric symptoms and Box 3 lists the changes that occur.

FIG 2 Neuroanatomical locations and neuropsychiatric symptoms of SLE. HPA, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal; NMDA, n-methyl-d-aspartate; NPSLE, neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus.

BOX 3 Diffuse changes in SLE

-

• Reduction in cerebral blood flow (Reference Yoshida, Shishido and KatoYoshida 2007)

-

• Loss of tissue integrity in brain parenchyma (Reference Welsh, Rahbar and FoersterWelsh 2007)

-

• Demyelination in white and grey matter (Huges 2007)

Therapeutic interventions

Treatment options for NPSLE are very limited, as therapy mainly comprises high-dose corticosteroids plus an immunosuppressive agent as an induction, followed by switching to a less toxic immunosuppressive agent and lower dose of corticosteroid as maintenance.

Only one small randomised controlled trial has been published comparing intravenous methylprednisolone and intravenous cyclophosphamide as treatments for NPSLE (Reference Baca, Lavalle and GarcíaBaca 1999). The study found that significantly more patients responded to treatment in the cyclophosphamide group compared with the methylprednisolone group.

Apart from immunosuppressive therapies for NPSLE, auxiliary treatments such as anti-psychotic, anti-anxiolytic and anti-epileptic agents are often required for controlling symptoms such as psychosis, anxiety and seizures.

Cognitive impairment and lupus

Cognitive impairment is one of the most common NPSLE syndromes, occurring in 20–80% of patients with lupus (Reference Hanly and HarrisonHanly 2005). The common cognitive abnormalities associated with NPSLE and their expected findings in neuropsychological tests are summarised in Table 1.

TABLE 1 Common cognitive abnormalities associated with neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus and expected findings in neuropsychological tests

| Cognitive abnormalities | Expected findings in neuropsychological tests a |

|---|---|

| Impairment in immediate, delayed, retrieval and global memory | Rey AVLT (trial I): problems with immediate word span; difficulties with immediate recall trial after five oral presentations of a 15-word list Rey AVLT (trial VII): problems with retrieval efficiency; delayed recall trial after 30 min |

| Impairment in visuospatial activities (e.g. affecting visual construction) | RCFT (copy phase): problems with constructional and organisational ability; failure to copy a complex figure WAIS (block design): failure to use blocks to construct replicas of designs RCFT (immediate recall phase): problems with visuospatial memory; failure to recall drawing after 3 min |

| Poor attention and concentration | WAIS (digit span): failure to repeat random number sequences forwards and backwards |

| Difficulties with abstract thinking | Providing superficial explanation when asked to interpret proverbs |

| Reduction in psychomotor speed | WAIS (digit symbol): failure to complete the task of filling the blank spaces with symbols paired with numbers in 90 s |

Assessment

As yet, no single bedside screening test is available, as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was shown to be unhelpful in assessing neuropsychiatric manifestations in patients with SLE (Reference Hanly and HarrisonHanly 2005). Reference Poole, Atanasoff and PelsorPoole et al (2006) found that cognitive deficits were better assessed by performance-based tests of disability rather than a self-report.

Brain imaging

Similar to schizophrenia, executive dysfunctions such as difficulty in multi-tasking, organisation and planning are common in NPSLE (Reference Hanly and HarrisonHanly 2005). In contrast to schizophrenia, the understanding of cognitive dysfunction did not evolve from the traditional ‘lesion-based’ approach, as earlier magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings were either non-specific or negative.

Diffusion tensor imaging has revealed early changes in the frontal lobe, genu corpus callosum and anterior internal capsule of patients with NPSLE (Reference Zhang, Harrison and HeierZhang 2007). Reference Monastero, Bettini and Del ZottoMonastero et al (2001) found that changes in psychiatric comorbidity such as depressive disorder parallel changes in cognitive function. Hence, psychotropic medication such as antidepressants may improve both mood status and cognitive function. The effect of cholinesterase inhibitors in individuals with lupus and cognitive impairment is not known.

Cognitive rehabilitation

Cognitive rehabilitation should also be considered, as it was shown to be promising in patients with schizophrenia and cognitive dysfunction (Reference Wykes, Reeder and CornerWykes 1999). Since cognitive impairment pertaining to NPSLE is heterogeneous, one approach to cognitive rehabilitation is to focus on subgroups of patients with specific cognitive abnormalities (e.g. of memory and attention). Larger, controlled trials of cognitive rehabilitation are required to identify specific and effective treatment strategies, long-term outcomes and cost-effectiveness of treatment.

Psychosis and lupus

Reference Appenzeller, Cendes and CastallatAppenzeller et al (2008) conducted a longitudinal study of patients with SLE for 9 years and identified primary psychotic disorder in 17% of the cohort. Of the patients presenting with primary psychotic disorder, 66% of cases were related to NPSLE, 31% were associated with corticosteroids and 3% were related to neither NPSLE or medication. Psychosis secondary to SLE at disease onset occurred in 21% of patients presenting with primary psychotic disorder and 45% of cases were associated with positive antiphospholipid antibodies.

Psychotic symptoms in SLE

Case study: Corticosteroid-induced psychosis

A 19-year-old woman was diagnosed with SLE when she presented with arthralgia, malar rash and subsequent diffuse progressive glomerulonephritis. Aggressive immunosuppression comprising intravenous pulse methylprednisolone followed by oral prednisolone and cyclophosphamide was given. Although her lupus activity was under control, she started to suffer from insomnia and mania. She accused somebody of following and harming her. She had no visual hallucinations, and neurological examination revealed no focal deficit. Thorough metabolic and infection screening was negative and no abnormalities were shown on brain MRI. The diagnosis of corticosteroid-induced psychosis was made and a subsequent prednisolone taper was accompanied by a progressive improvement of her psychotic symptoms over the next 3 weeks. Adjunctive antipsychotics were titrated to zero over a further 2 months.

Cases similar to that of the young woman described above are often referred to psychiatrists. In referrals of young people with a first episode of psychosis it is important to rule out physical disorders such as SLE (Reference Fernandez, Gorriti and Garcia-VicunaFernandez 2007). The main clinical features of psychosis in NPSLE are acute delusions and hallucinations. As the typical age at presentation of NPSLE-related psychosis is in the early 20s, it is often difficult to differentiate it from schizophreniform psychosis. Corticosteroids also contribute to psychosis through ischaemia and subsequent hippocampal damage (Reference Wolkowitz, Reus and CanickWolkowitz 1997). Table 2 summarises the differences between psychosis related to NPSLE and to corticosteroids.

TABLE 2 Comparison between neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (NPSLE) psychosis and corticosteroid-induced psychosis (Reference Appenzeller, Cendes and CastallatAppenzeller 2008)

| Onset | Risk factors | Resolution | Predictors of recurrence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPSLE psychosis | Acute Mean age at onset: 25 years | High disease activity Other NPSLE manifestations such as depression or cognitive impairment Absence of cutaneous manifestations such as malar rash and photosensitivity |

May require antipsychotic treatment | Positive antiphospholipid antibodies in moderate to high titres |

| Corticosteroid- induced psychosis | New onset of psychosis that appears temporally within 8 weeks of being admitted to hospital or augmentation of steroids | Hypoalbuminemia | Psychosis will be resolved completely after reduction of steroid dosage without additional immunosuppressive agents | Increments of corticosteroid to control systemic manifestations |

Antipsychotics and their side-effects

Antipsychotic medication commonly used in schizophrenia can also be given to patients with NPSLE. Lupus-related bodily changes often affect the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antipsychotic drugs, leading to side-effects that can be persistent and disabling. Chlorpromazine, for example, is well known to cause drug-induced lupus. It may aggravate photosensitivity and complicate the existing manifestations of lupus (Reference Harth and RapoportHarth 1996). Although recent studies have indicated that the new atypicals may have a more favourable side-effect profile, agranulocytosis from atypical antipsychotics such as olanzapine has been reported (Reference Su, Wu and TsangSu 2007).

Research addressing the use of first-generation antipsychotics in people with lupus and psychosis is sparse. These drugs are not recommended because they may exacerbate NPSLE-associated movement disorders (Reference Nishimura, Omori and HorikawaNishimura 2003).

No data are yet available from controlled trials regarding the efficacy and safety of second-generation antipsychotics. As stroke is one of the NPSLE syndromes, risperidone and olanzapine should be avoided. These drugs are a known risk factor for cerebrovascular adverse events in elderly patients without SLE (Reference Herrmann and LanctôtHerrmann 2005). Quetiapine and sulpiride are recommended, as there are no reports of adverse effects in individuals with NPSLE.

In severe NPSLE, pulsed intravenous cyclophosphamide has produced significant improvement in psychotic symptoms (Reference Bodani and KopelmanBodani 2003). The medication was well tolerated in adult and paediatric patients.

Non-pharmacological interventions

Research into non-pharmacological treatment for NPSLE-associated psychosis is limited. Although there is compelling evidence to support the use of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) in modifying delusional beliefs and controlling hallucinations in people with schizophrenia (Reference Garety, Kuipers and FowlerGarety 1994; Reference Kuipers, Garety and FowlerKuipers 1997), no study has assessed the effect of CBT on patients with NPSLE-associated psychosis; however, the same principles can be applied.

Clinicians should address the nature of untreated SLE-related psychosis and its negative impact on both patient and caregivers if not treated. Psychoeducation is often useful to enhance insight and understanding.

Depression, anxiety and lupus

Depression and anxiety are the most frequently encountered psychiatric problems in patients with lupus (Reference WekkingWekking 1993), but there are no specific features that are unique to SLE (Reference Hanly and HarrisonHanly 2005). The use of different criteria for diagnosis has resulted in a wide prevalence (24–57%) across studies (Reference Brey, Holliday and SakladBrey 2002). For practical purposes, it is probably most helpful to consider depression and anxiety as dimensions rather than categories (Reference Goldberg and HuxleyGoldberg 1992).Footnote † Depression and anxiety in SLE are often accompanied by other problems, such as poor anger control.

In SLE, depression that presents with predominantly somatic complaints (e.g. pain and lethargy) may remain undiagnosed as these symptoms overlap those of lupus itself. For medical patients such as those with SLE, the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) has low sensitivity in detecting depression as its questions are too direct (e.g. have you had suicidal thought in the past 3 weeks?) and are intended for psychiatric patients with clear-cut depressive disorder. Most medical patients will get a very low score on the HRSD but this does not mean they are not depressed or have good mental health. Reference Stoll, Kauer and BuchiStoll et al (2001) therefore proposed the routine use of the Short Form (SF)–36 to detect depression when assessing patients with SLE. The SF–36 mental health score closely correlates with the severity of depression on the HRSD but its questions are more relevant to the everyday life of people with SLE (e.g. have your physical health or emotional problems interfered with activities like visiting relatives?).

Antidepressants

Data regarding the use of antidepressants in individuals with SLE stem from just a few case reports. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can be useful in treating depression in NPSLE, and psychiatrists need to be aware of specific side-effects of different antidepressants. Reference Cassis and CallenCassis et al (2005) and Reference Hill and HepburnHill et al (1998) have reported erythematosus skin lesions related to bupropion and sertraline use. Fluoxetine can cause extrapyramidal side-effects (Reference Fallon and LiebowitzFallon 1991).

Reference Douglas and SchwartzDouglas and colleagues (1982) reported a case of depression caused by lupus cerebritis that was successfully treated by electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). With the development of a variety of anti-depressants, the use of ECT to treat depression in people with SLE has become second-line in clinical practice. Nevertheless, ECT does play a role in treating manic psychosis and catatonia stemming from NPSLE (Reference Ditmore, Malek-Ahmadi and MillisDitmore 1992).

The role of psychological therapies and non-pharmacological strategies such as CBT, cognitive remediation relaxation therapy, sleep hygiene and regular exercise should also be considered.

Fatigue and lupus

Fatigue has been reported as one of the most common and most disabling symptoms in SLE, with a prevalence of up to 80% (Reference Krupp, LaRocca and MuirKrupp 1990). Eleven per cent of patients in the UK fulfilled the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for fibromyalgia (Reference Taylor, Skan and ErbTaylor 2000), a condition characterised by chronic fatigue syndrome for more than 3 months and multiple tender spots.

Case study: Fibromyalgia in SLE

A 50-year-old housewife with long-standing SLE has been treated with prednisolone and azathioprine for the past 3 years. She started to complain of easy fatigue, poor sleep and generalised body aches and pains 6 months ago. In addition, she noted having a dry mouth and dysuria; no other systemic symptoms were observed. Physical examination revealed multiple tender spots over the neck and trunk. Thorough investigation showed no evidence of arthritis and her urine was sterile. Serology revealed no evidence of active lupus and metabolic screening did not suggest electrolyte imbalance or endocrinopathy. She was referred by her rheumatologist to a psychiatrist and the diagnosis of fibromyalgia was made. Eight weeks after treatment with fluoxetine, the symptoms of fibromyalgia substantially improved.

Box 4 summarises the key factors that contribute to fatigue in SLE. Reference Tench, McCurdie and WhiteTench et al (2000) have suggested that myalgia and arthralgia related to lupus may disturb sleep, resulting in daytime fatigue. Increased levels of anxiety and depression are also associated with increased SLE-related fatigue (Reference Ward, Marx and BarryWard 2002).

BOX 4 Factors contributing to fatigue in SLE

-

• Insomnia and high bodily pain

-

• Depression

-

• Anxiety

-

• Loss of muscular power

-

• Low levels of aerobic activity

-

• Associated fibromyalgia

Clinical assessment

Symptoms of fatigue can be rated using the Fatigue Severity Score developed by Reference Krupp, LaRocca and MuirKrupp et al (1990). It is also worth considering laboratory tests to rule out underlying medical conditions such as anaemia, hypothyroidism and malignancies.

Treatment

Treatment of fatigue in individuals with SLE is mainly symptomatic. Concomitant depressive disorder and sleep disturbance which may lead to fatigue should be identified and treated (Reference McKinley, Ouellette and WinkelMcKinley 1995). An SSRI such as fluoxetine may improve mood and energy levels.

Psychological interventions such as lifestyle changes, including sleep hygiene, relaxation and regular exercise programmes, are safe and helpful. Psychological interventions such as lifestyle changes, including sleep hygiene, relaxation and regular exercise programmes, are safe and helpful. Reference Tench, McCarthy and McCurdieTench et al (2003) conducted a randomised controlled trial in which patients with SLE were assigned to a 12-week programme of aerobic exercise, relaxation therapy or no intervention. At the end of the 12 weeks they compared the participants' physiological, symptomatic and functional changes. Graded exercise led to significantly greater overall improvement than relaxation therapy or no intervention.

The role of the psychiatrist

In- and out-patient referrals are the usual routes by which rheumatologists obtain psychiatric opinions on patients with NPSLE, but they have insufficient face-to-face communication with psychiatrists. In the consultation–liaison model of practice, however, psychiatrists attend ward rounds and discuss the diagnosis and management plan with the rheumatology team. The advantages of this include better communication, which allows the psychiatrist a broader view, clarifies uncertainties and leads to agreement on the diagnosis. It may involve a longitudinal follow-up to address difficult issues and review responses to various treatment strategies. The psychiatrist needs to formulate a framework for assessing patients with NPSLE. The psychiatrist's role in the management of NPSLE is summarised in Box 5.

BOX 5 The psychiatrist's role in the management of NPSLE

-

• The psychiatrist can help the general practitioner and the rheumatology team by:

-

• assessing the reasons for referral, precipitating factors and potential risk

-

• empathetic listening and eliciting an emotional response from the patient regarding their view of the illness, threat to self-image, perceived control over the illness, and prognosis

-

• obtaining a collateral history from the general practitioner and family as the patient may be cognitively impaired

-

• linking the pathogenesis of NPSLE and psychiatric symptoms

-

• determining the role of psychosocial factors in the causation and maintenance of psychiatric symptoms

-

• explaining the psychiatric formulation and decisions to other specialists, paramedical staff, patient and family

-

• advising on the pharmacological and psychological management of psychiatric symptoms

-

• coordinating psychiatric services such as cognitive remediation

-

• training practice nurses and general practitioners to provide psychological interventions in the primary care or community setting

Conclusions

Psychiatric symptoms often occur in patients with SLE. Although the American College of Rheumatology nomenclature for NPSLE is comprehensive, psychiatric symptoms described in individuals with SLE are neither sensitive nor specific. Prompt recognition of psychiatric symptoms, with exclusion of aetiologies such as infection, metabolic or endocrine dysfunction and drug intoxication, is absolutely necessary.

Further research is required to explore the possibility of using anti-neuronal antibodies, electroneurophysiological studies and diffusion tensor imaging in diagnosing NPSLE, and to assess the efficacy of psychotropic medication and psychotherapy.

Close liaison between psychiatrists and rheumatologists undoubtedly facilitates effective assessment and management of the disease, which can improve the quality of life of individuals with SLE and associated psychiatric syndromes.

EMIs

Theme: Laboratory markers

Which of the laboratory markers below is most strongly associated with the following NPSLE symptoms?

-

1 ‘I hear a voice outside my house. She always sings to me. When I go out and check, there is nobody around.’

-

2 A young female with SLE complains of low mood and is noted to have cognitive decline.

-

3 A 22-year-old woman presented with malar rash on her face. What test would you order as a screening test?

Options

-

a Anti-double stranded DNA

-

b Complement proteins

-

c Anti-NMDA antibody

-

d Anticardiolipin antibody

-

e Antinuclear antibody

-

f Antiphospholipid antibodies

Theme: Neuropsychological tests

A 22-year-old architecture student presents with 5 years' history of SLE. She has become increasingly forgetful and appears depressed. Her main complaint is of poor attention. Her academic results have deteriorated as she has difficulty with drafting and designing new buildings.

-

4 She has difficulty recalling three items during the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE). You are concerned with her memory. Which test would you use to assess her immediate, delayed, retrieval and global memory?

-

5 As an architecture student, she is failing her assignment in drafting and design. You are concerned with her visuospatial abilities. Which test would you use to assess her constructional and organisation abilities?

-

6 On the MMSE, she appears to be slow. You are concerned with psychomotor retardation. Which test would you use to assess her psychomotor speed?

Options

-

g Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test

-

h Rey Complex Figure Test

-

i Serial 7, 3 stage command orientation

-

j Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (digital span)

-

k Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (digit symbol)

-

l Stroop test

Theme: Management of NPSLE

Which of the above actions is the most appropriate in the following scenarios?

-

7 The general practitioner insists that his patient is frankly psychotic and needs to be detained in hospital under the Mental Health Act.

-

8 A patient with SLE feels that their illness is hopeless and there will be no cure.

-

9 A 28-year-old patient with SLE complains of tiredness and low energy level. They are not keen to take additional medication.

Options

-

m Empathetic listening and eliciting emotional response from the patient

-

n Linking the pathogenesis of NPSLE and psychiatric symptoms, and offering explanation to other professionals

-

o To prescribe an antidepressant

-

p To prescribe a benzodiazepine

-

q Encouraging the patient to do exercise on a regular basis

EMI answers

| 1 | f | 4 | g | 7 | n |

| 2 | c | 5 | h | 8 | m |

| 3 | e | 6 | k | 9 | q |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.