Assessments (Boxes 1 and 2) are an essential and integral part of medical education. Assessments enable us to make decisions about trainees – whether and how much they have learnt and whether they have reached the required standard (Reference RowntreeRowntree, 1987). They can influence the way a student learns (Reference BroadfootBroadfoot, 1996), the motivation a student has for learning and the content of what is learnt. For an assessment method to be acceptable it needs to be valid, reliable, practical and have a positive effect on a trainee's learning (Reference Newble and CannonNewble & Cannon, 2001).

Box 1 Some common and abbreviations acronyms

| CBD | Case-based discussion |

| CEX | Clinical evaluation exercise |

| DOP | Directly observed procedure |

| Mini-CEX | Mini-clinical evaluation exercise |

| MSF | Multisource feedback |

| OSATS | Objective structured assessment of technical skills |

| OSCE | Objective structured clinical examination |

| RITA | Record of in-training assessment |

| SP | Standardised patient |

| WPA | Workplace assessment |

Box 2 Useful definitions of educational terms related to assessment

| Assessment | A systematic process of collecting and interpreting information about an individual in order to determine their capabilities or achievement from a process of instruction |

| Formative assessment | Occurs during the teaching process and provides feedback to the trainee for their further learning |

| Summative assessment | Occurs at the end of the learning process and assesses how well the trainee has learnt |

| Criterion-referenced assessment | The pass mark is determined against achievement of a predetermined standard, for example those who score over 65% will pass |

| Norm-referenced assessment | The pass mark is determined by a trainee's performance compared with that of others, for example the top 45% of students will pass |

| Appraisal | An on-going process designed to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of a person in order to encourage their own professional development and their contribution to the development of the organisation in which they work |

| Evaluation | The process of collecting and interpreting information about an educational process in order to make judgements on its success and to make improvements (note: in the USA this term is sometimes used to mean assessment, as defined above) |

| Validity | The degree to which a test measures what it is intended to measure, for example whether the content of an assessment covers the content of the syllabus (content validity) and whether a test predicts the future performance of a student (predictive validity) |

| Reliability | The degree to which one can depend on the accuracy of a test's results, for example whether different examiners would award the same marks given the same candidate performance (interrater reliability) or whether the same set of students would score the same marks if the test were repeated with them under the same conditions (test–retest reliability) |

Poorly selected assessment methods can lead to passive or rote learning (to get through an exam ination), which is associated with a rapid decay of knowledge and sometimes an inability to apply it in real situations (Reference Stobart and GippsStobart & Gipps, 1997). The main components of undergraduate and postgraduate assessment in medicine have traditionally been written and clinical examinations. These have strengths and weaknesses. The majority are now better in an all-round sense in that they test a number of dimensions, for example knowledge, problem-solving and communication skills, but by definition they are still one-off assessments. A single, sometimes non-clinical, event establishes what a doctor knows (e.g. in a multiple choice paper), knows how to do (e.g. in a short-case viva or extended matching questions) or is able to show how to do ‘on the day’ (e.g. in a long case or an objective structured clinical examination, an OSCE). They are basic tests of competence, not assessments of day-to-day performance. They specifically do not assess other attributes necessary for a person to perform consistently well as a doctor, for example team-working skills.

The outcome-based approach

Current developments in medical education and training dictate the necessity and give the opportunity for significant change in all aspects of the assessment system. Changes that have occurred in undergraduate training in the decade or so since the publication of the first edition of Tomorrow's Doctors (General Medical Council, 1993) are now being followed by similar initiatives in postgraduate education.

The current shift in medical education is towards outcome-based learning. Outcome-based education can best be summed up as results-oriented thinking. It is the opposite of input-based education, where the emphasis is on the educational process, almost regardless of the result. In outcome-based education, the outcomes agreed for the curriculum guide what is taught and, importantly here, what is assessed. Exit outcomes, i.e. the doctor's performance capabilities, are therefore a critical factor in determining both what is to be learnt (the curriculum) and what is to be tested (the assessments). Assessment programmes in outcome-based education must be systematic and include criteria for each of the abilities defined.

The focus is on the care delivered to different patients and in different settings.

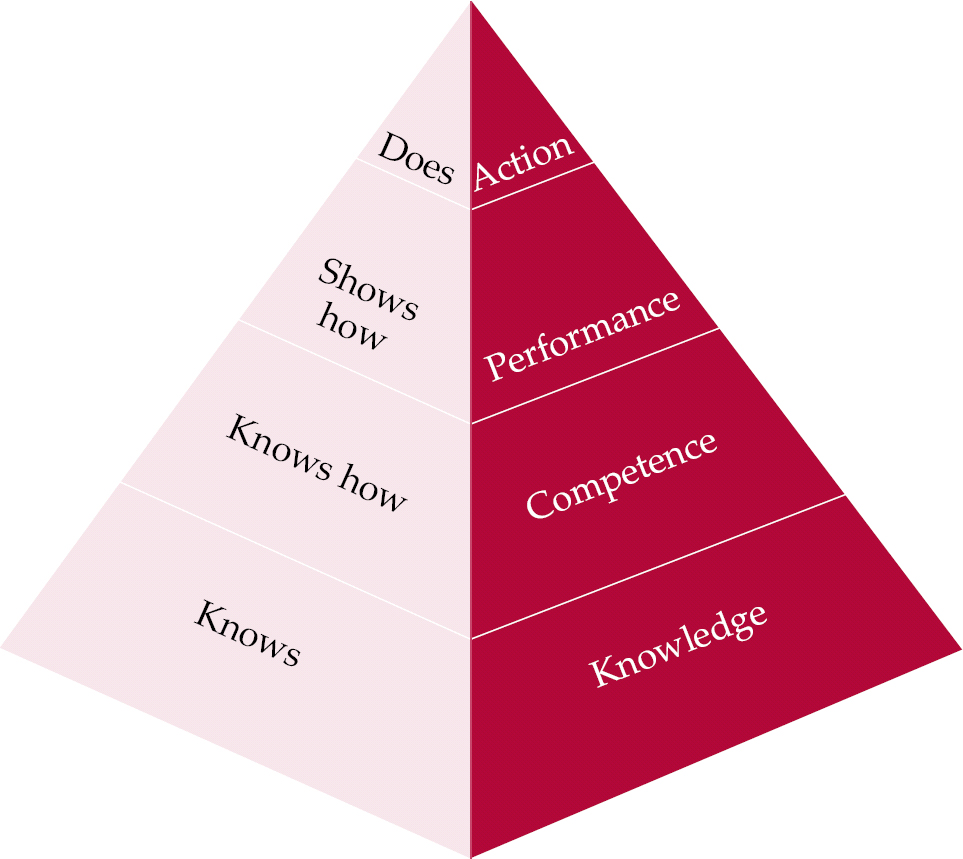

Newer assessment methods need to be able to assess what a doctor actually does in everyday practice (Reference MillerMiller, 1990), rather than one-off assessments of what they ‘know’, ‘know how’ or can ‘show how’ (Fig. 1). This requirement has led to the rapid development of suitable assessment tools and schedules, generally brought together under the title of workplace assessments.

Fig. 1 Miller's framework for assessment (after Reference MillerMiller, 1990, with permission).

Workplace assessment is one of the cornerstones of the emergent Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board (PMETB; http://www.pmetb.org.uk/), whose vision includes the rapid expansion of such assessments and their incorporation into a strategy that links assessment in the workplace with examinations of knowledge and clinical skills throughout training. PMETB states within its principles that assessment(s) must be fit for purpose, based on curricula, mapped to a blueprint of curricula content and use methods that are valid, reliable, psychometrically supported and in the public domain (Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board, 2004a ).

All assessment systems and, indeed, curricula must now satisfy PMETB's published requirements (Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board, 2004a , b ).

Workplace assessment

Workplace assessment (inevitably abbreviated to WPA) taps into the potentially best way of collecting data on trainees’ performance: personal witnessing of their interactions with patients over a period of time. It has the advantage of high validity precisely for this reason. However, it is not feasible to monitor every interaction every day, hence the need to develop efficient and effective techniques for optimising the process.

To ensure that the right competencies are learnt and validly and reliably assessed, workplace assessments in psychiatry, as in medicine in general, need to be considered alongside the development of curriculum models. The clear advantages of assessment in the workplace include the opportunities for feedback and the educational value conferred by putting emphasis on ‘real-time’ assessment. It is a strange fact of medical life that trainees are infrequently formally observed in daily encounters with patients. This limits the opportunity for continuous and developmental feedback on clinical performance. The introduction of assessment in the workplace means that far greater emphasis can be placed on patient-based learning and far more detailed, valid and reliable observations of doctors’ clinical performance can be obtained.

It is well documented that assessment drives learning (Reference BroadfootBroadfoot, 1996). Thus, if Dr A, a senior house officer, is assessed only by a multiple choice paper, she is likely to direct her learning towards facts from books. If she is assessed in the workplace, she is more likely to focus her learning on patient-based activities.

Benefits of multiple assessments and assessment methods

In an ideal system the trainee is tested by multiple raters using different tools repeatedly over a period of time. Clearly, no single rating is able to provide the whole story about any doctor's ability to practise medicine, as this requires the demonstration of on going competence across a number of different general and specific areas. Patterns emerge when an individual is subject to many assessments, thus diminishing problems of sampling and interrater reliability.

A further important reason for using different types of assessment is the specificity of the various assessment tools themselves. The development of a competency-based approach to training sets the most challenging agenda of accurately assessing a student both in individual components of competency and in overall performance.

Much of the existing data on the use of workplace-based assessments is derived from other medical specialties and often from other countries (Reference Norcini, Blank and ArnoldNorcini et al, 1995). In psychiatry, we must develop or adapt existing assessment methods and assessors in order to produce accurate and defensible data.

The strategy of using multiple assessments could quickly become burdensome, since the gold – you might say platinum – standard would be one of infinite measurements applied daily by everyone involved with the trainee. A compromise will have to be reached between a method that gains sufficient information to draw a full picture of the trainee's developing performance and the need to run services on a daily basis.

The picture emerging in the UK is based on PMETB's curriculum for the foundation years of postgraduate education and training, the core competency requirements of which are summarised in Table 1. The assessment system will take a three-tiered approach, encompassing educational (not National Health Service) appraisal, assessment and annual review (Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board, 2005).

Table 1 Foundation programme core competencies (after Foundation Programme Committee of the Academy of the Medical Royal Colleges, 2005)

| Domain | Skills/competencies |

|---|---|

| Good clinical care | History-taking; patient examination (includes mental state examination); record-keeping; time management; decision-making. Understands and applies the basis of maintaining good quality care; ensures and promotes patient safety; knows and applies the principles of infection control; understands and applies the principles of health promotion/public health; understands and applies the principles of medical ethics and relevant legal issues |

| Maintaining good medical practice | Self-reflective learning skills; directs own learning; adheres to organisational rules/guidelines; appraises evidence base of clinical practice; employs evidence-based practice; understands the principles of audit |

| Relationships with patients and communication | Demonstrates good communication skills |

| Working with colleagues | Working in teams; managing patients at the interface of different specialties, including primary care, imaging and laboratory specialties |

| Teaching and training | Understands educational methods; teaches medical trainees and other health professionals |

| Professional behaviour and probity | Consistently behaves professionally; maintains own health; self-care |

| Acute care | Assessing, managing and treating acutely ill/collapsed/unconscious or semi-conscious/convulsing/psychotic/toxic patients or patients who have harmed themselves: this includes giving fluid challenge, analgesia and obtaining an arterial sample for blood gas. Recognising own limits and asking for help appropriately; handing over information to relevant staff; taking patients’ wishes into consideration; resuscitation of patients, including consideration of advance directives |

A thorough discussion of some of the different assessment tools and how they may be used follows. It must be recognised though that this is an area of considerable growth. New tools are being developed and many of these will become part of the collection of evidence documented in individual portfolios in years to come.

Assessment tools and methods

The mini-clinical evaluation exercise

The mini-clinical evaluation exercise (mini-CEX) has been adapted from the clinical evaluation exercise (CEX), an instrument designed by the American Board of Internal Medicine for assessing junior doctors at the bedside. The CEX is an oral examination during which the trainee, under the observation of one assessor who is a physician, takes a full history and completes an full examination of a patient to reach a diagnosis and plan for treatment. It takes about 2 h to complete. The physician gives immediate feedback to the trainee and documents the encounter. Later the trainee gives the evaluator a written record of the patient's work-up. The CEX has limited generalisability (Reference Kroboth, Hanusa and ParkerKroboth et al, 1992; Reference Noel, Herbers and CaplowNoel et al, 1992) because it is limited to one patient and one assessor, making it a snapshot view, vulnerable to rater bias.

The mini-CEX (Reference Norcini, Blank and DuffyNorcini et al, 2003) involves several assessments, each of 20 min duration, that are conducted at intervals during training. Each clinical encounter is selected to focus on areas and skills selected from the foundation curriculum (Foundation Programme Committee of the Academy of the Medical Royal Colleges, 2005) (see Table 1). A trainee will undertake six to eight mini-CEXs over the course of foundation-level training (Table 1). Each assessment will be rated by a single but different examiner and will assess skills not previously examined. Rather than completing a full history and examination the trainee is asked to conduct a focused interview and examination, for example to assess the suicidal intent of a patient. Assessment takes place in settings in which doctors would normally see patients (out-patient clinics, on the wards) and immediate direct feedback is given to the trainee.

The mini-CEX has been demonstrated to have good reproducibility (Reference Norcini, Blank and ArnoldNorcini et al, 1995), validity and reliability (Reference Kroboth, Hanusa and ParkerKroboth et al, 1992; Reference Durning, Cation and MarkertDurning et al, 2002; Reference Kogan, Bellini and SheaKogan et al, 2003) in general medicine.

The number of mini-CEXs required in higher specialist training is yet to be determined. The studies on reproducibility suggest that, for a given area of performance, at least four assessments are needed if the trainee is doing well and more than four if performance is marginal or borderline (Reference Norcini, Blank and ArnoldNorcini et al, 1995).

As yet the mini-CEX has not been evaluated specifically with psychiatric trainees. Early experience suggests that the practical planning (e.g. coordinating diaries to book the session and to give time to find a case that meets the criteria) should be done well in advance. The time required for an assessment stated in the foundation-years curriculum (Foundation Programme Committee of the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, 2005) may be an underestimate and resources are required in terms of time and patients. Importantly, the examiners will require extensive training.

The standardised patient examination

A standardised patient is a person who is trained to take the role of a patient in a way that is similar and reproducible for each encounter with different trainees. Hence they present in an identical way to each trainee. The standardised patient may be an actor, an asymptomatic patient or a patient with stable, abnormal signs on examination. Standardised patients can be employed for teaching history-taking, examination, communication skills and interpersonal skills. They can also be used in the assessment of these skills. The advantages of using standardised patients are that the same clinical scenario is presented to each trainee (reliability) and they enable direct observation of clinical skills (face validity). Feedback can be immediate and can also be given from the point of view of the patient – although the standardised patient would need to be trained to do this in a constructive manner.

Using standardised patients has high face validity. Reliability varies from 0.41 to 0.85 (Reference Holmboe and HawkinsHolmboe & Hawkins, 1998), increasing with more cases, shorter testing times and less complex cases. The reliability of this type of assessment is better when assessing history-taking, examination and communication skills than for clinical reasoning or problem-solving. Standardised patients have been used in multi-station exams such as OSCEs, where trainees perform focused tasks at a series of stations.

Standardised patients have been used as a means of integrating the teaching and learning of interpersonal skills with technical skills and giving direct feedback to trainees. If the student–patient encounter is video recorded the student can subsequently review the tape as an aid to learning (Reference Kneebone, Kidd and NestelKneebone et al, 2005). Video recordings can also be used as part of a trainee's assessment, for example by enabling multiple raters to assess the individual (thereby increasing reliability). For workplace-based assessments the standardised patient would be seen in a setting where the candidate normally sees patients.

Case-based discussion

Case-based discussion is also known as chart-stimulated recall examination (Reference Munger, Mancall and BashbrookMunger, 1995) and strategic management simulation (Reference Satish, Streufert and MarshallSatish et al, 2001). The trainee discusses his or her cases with two trained assessors in a standardised and structured oral examination, the purpose of which is to evaluate the trainee's clinical decision-making, reasoning and application of medical knowledge with real patients. The assessors question the trainee about the care provided in predefined areas – problem definition (i.e. diagnosis), clinical thinking (interpretation of findings), management and anticipatory care (treatment and care plans) (Reference Southgate, Cox and DavidSouthgate et al, 2001). The trainee is rated according to a prescribed schedule; a single examination takes about 10 min, and there will be about six to eight examinations during the course of training. The assessors (two independent raters) visit the trainee's place of work and the patient's notes/trainee's documentation are used as the focus of the exam.

Patients must be selected to form a representative sample. The trainee's performance is determined by combining scores from a series for a pass/fail decision. Reliabilities of between 0.65 and 0.88 have been reported in other medical specialties (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education & American Board of Medical Specialties, 2000). Assessors must be trained in how to question and how to score responses.

Case-based discussion is potentially easy to implement but it requires that trainees manage sufficient and sufficiently varied cases to give a valid and reliable sample. Extensive resources and expertise will be required to standardise the examination if it is to be used for ‘high-stakes’ assessments.

Directly observed procedures

Directly observed procedures or objective structured assessment of technical skills are similar to the mini-CEX. The process has been developed by the Royal College of Physicians to assess practical skills (Reference Wilkinson, Benjamin and WadeWilkinson et al, 2003). Two examiners observe the trainee carrying out a procedural task on a patient and independently grade the performance. This form of assessment lends itself well to medical specialties where the acquisition of practical skills is important. Examples include suturing a wound, taking an arterial blood sample and performing a lumbar puncture.

In psychiatry it is less obvious what we would observe because psychiatrists are less involved with practical procedures. One possibility would be assessing how a trainee administers electro-convulsive therapy (ECT), but this is not frequently prescribed. Alternatively it could be used to assess less concrete skills such as conducting a risk assessment on a patient who has recently taken an overdose or preparing a patient for ECT, explaining the process and obtaining consent. In practice, there could be considerable overlap with the mini-CEX.

Multisource feedback

The need for a measure of the humanistic aspects of a doctor's practice is increasingly accepted. Multisource feedback, which is also known as 360° assessment, consists of measurements completed by many people in a doctor's sphere of influence. Evaluators completing the forms are usually colleagues, other doctors and members of the multi-professional team. Rarely are patients or families invited to participate. A multisource assessment can be used to provide data on interpersonal skills such as integrity, compassion, responsibility to others and communication; on professional behaviours; and on aspects of patient care and team-working. The data collected are summarised to give feedback.

Raters tend to be more accurate and less lenient when an evaluation is intended to give formative rather than summative assessment (see Box 2 for definitions) (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education & American Board of Medical Specialties, 2000). A body of published work is emerging (Reference Evans, Elwyn and EdwardsEvans et al, 2004; Reference BakerBaker, 2005) that suggests the clear need to differentiate between a tool to be used in developmental appraisal and a method for identifying poor performance. This differentiation is not always apparent. There must also be a note of caution surrounding the assessment of behaviours that are not directly observable. None the less, multisource feedback can make a vital contribution to the measurement and improvement of an individual doctor's performance.

There remain two practical challenges. First, construction of tools that all potential assessors can use and second, the compilation of the data into a format that can be reported confidentially to the trainee.

Other assessments

Other assessment tools exist although not strictly for workplace assessments. However, they are worthy of a mention because they have the potential to complement workplace assessments for a complete all-round assessment package.

Written examination

Although workplace assessments cover the trainees’ performance they are weak at assessing their knowledge in a broad sense. This can be done using multiple choice or similar written papers such as those listed in Box 3.

Box 3 Written assessments

Multiple choice questions The candidate has to select the correct response to a stem question or statement from a list of one correct and four incorrect answers (other formats can be used)

Best of five The candidate has to select the most likely answer out of five options, some of which could be correct but one is more likely than the others

Extended matching questions The candidate has to match one out of several possible answers to each of a series of statements

Portfolios

A portfolio is a collection of material, collated by the individual over time, used to demonstrate their chronological learning, performance and development. It can enable individuals to reflect on their abilities and highlight areas that could be improved to enhance the quality of their practice. There are numerous models for portfolio use. In medicine, portfolios tend to be used both formatively (to improve one's own practice) and summatively (for recertification and revalidation). However, there is little evidence to support their use for the latter.

For portfolios to be a valid and reliable assessment tool trainees need to be well prepared in using them and their content must be uniform. Raters should be well trained and experienced (Reference Roberts, Newble and O'RourkeRoberts et al, 2002). Assessment criteria should be consistent with what doctors are expected to learn. The NHS Appraisal Toolkit (http://www.appraisals.nhs.uk) includes a model portfolio for doctors that covers the areas outlined in the GMC's Good Medical Practice (General Medical Council, 2001) and summarised in Box 4.

Box 4 Summary of the duties of a doctor registered with the GMC

-

• Good clinical care

-

• Maintaining good medical practice

-

• Partnership with patients

-

• Working with colleagues and in teams

-

• Assuring and improving the quality of care

-

• Teaching and training

-

• Probity

-

• Health

The advantage of establishing a portfolio during postgraduate training is that it is flexible and can therefore accommodate the individual's varying needs as they proceed along chosen career paths and within different specialties.

The record of in-training assessment

The record of in-training assessment (RITA) is a portfolio of assessments that are carried out during medical training. It used throughout UK postgraduate medical training, and is mandatory for specialist registrars and is being introduced for senior house officers. The purpose of this record is to determine whether or not an individual has completed each training period satisfactorily and can proceed with training and ultimately enter the specialist register. The Guide to Specialist Registrar Training (Department of Health, 1998) describes the RITA system, but the generality of its recommendations has resulted in widespread variation between regions and specialties.

A RITA is an assessment record, not an assessment in itself, and it currently relies on in-service assessments that are almost always retrospective and either lack evidence or use unsubstantiated evidence of competence (Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board, 2005). The clear opportunity now arises to clarify and strengthen a RITA-type system, as new workplace-based assessment processes begin to yield recordable evidence of performance.

Resource requirements: the professionalisation of training

The implementation of an assessment structure that adds value to the system for training and accreditation of doctors will require urgent attention to resources. Extensive assessor training will be needed to ensure uniformity of assessment at a local level. As most consultants will be expected to carry out workplace assessments, training that requires assessors to take professional leave may pose a particular problem. One long-term solution might be to incorporate ‘training the trainers’ into the curriculum, so that doctors in training are themselves learning to become the trainers of the future (Reference Vassilas, Brown and WallVassilas et al, 2003).

Unfortunately, the financial implications of producing robust assessment systems have yet to be calculated. Increasing the level of trainee supervision and assessment will almost certainly result in some reduction in time available for service commitment, although this may be difficult to quantify in advance.

The schedule of assessments selected will be mapped to the foundation years’ curriculum (Foundation Programme Committee of the Academy of the Medical Royal Colleges, 2005) in a blueprint. The Royal College of Physicians has published a model based on Good Medical Practice and the PMETB Standards for Curricula (2004b) that may serve as an exemplar (Joint Committee on Higher Medical Training, 2003). It will be necessary to establish clear standards for the process and outcome of assessment and then to monitor those standards across programmes. The obvious danger will be that standards will not be equivalent across the UK and abroad.

In a system that relies on assessment by senior colleagues it is likely that very few trainees will be deemed unsatisfactory. There will remain a need for another (national, independent) assessment, perhaps near the end of specialist training. For trainees who continue to perform unsatisfactorily a robust system for career counselling will be required.

Conclusions

Currently, workplace-based assessment is under-utilised and the way in which it is implemented and documented, principally through the RITA, is variable and often of poor standard. Assessors may be reluctant to make unfavourable judgements and may pass trainees by default, in the absence of real evidence. However, it is expected that workplace-based assessment will become increasingly common.

By its very nature workplace-based assessment has the advantage of high face validity, although its predictive validity is currently unknown (as is the case for almost all existing postgraduate medical examinations). Many of the specialties for which the assessments were designed have published reliability data, but there is a pressing need for comparable data in the field of psychiatry. Without evidence specific to our specialty, the public and professionals may well lack confidence in decisions based on the workplace-based assessment process.

Workplace-based assessment is an excellent source of information for teaching, educational supervision and feedback, as well as providing evidence of satisfactory (or unsatisfactory) progress and achievement. The system is founded on self-directed learning, so that the trainee schedules each assessment. Trainees will require a good level of organisation and motivation to achieve this. The significant benefit for trainees is the receipt of immediate and constructive feedback.

One of the most likely consequences of the contemporary reforms in postgraduate medical education is an increase in the amount of educational activity in the workplace and this must be properly underpinned if the opportunities offered are to be realised. Each college or specialty must develop a strategy involving workplace-based assessment and examinations of knowledge and clinical skills relating to the entire training period. The tools that we have described here are some of the basic building blocks from which the curriculum and assessment strategy of the future will be constructed.

Declaration of interest

The views expressed are personal and do not represent the views of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

MCQs

-

1 Assessments:

-

a do not influence the content of what a trainee learns

-

b should have high reliability and validity

-

c are the same as appraisals

-

d are useful if they are used only to assess a trainee's knowledge

-

e are better when they are summative.

-

-

2 Workplace-based assessments:

-

a will not be time consuming for the assessors

-

b aim to measure what a doctor does in day-to-day practice

-

c can include assessments by patients

-

d include multiple choice questions as a form of assessment

-

e should be organised by the trainee.

-

-

3 Multisource feedback is useful for assessing:

-

a a trainee's team-working skills

-

b a trainee's ability to do a lumbar puncture

-

c a trainee's ability to communicate effectively

-

d whether or not a trainee can tie their shoelaces

-

e a trainee's ability to relate to others.

-

-

4 Portfolios:

-

a are ideal for summative assessments

-

b are a chronological record of a doctor's performance

-

c enable one to reflect on one's own practice

-

d enable one to identify areas of weakness in one's own practice

-

e require that training be provided in their use and assessment.

-

-

5 Direct observation of procedural skills:

-

a requires that the assessors be trained

-

b can be adapted to assess skills in psychiatric practice

-

c has been developed more for other medical specialties

-

d is highly relevant to psychiatric practice

-

e could be used to assess obtaining patient consent to treatment.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | T | a | F | a | T |

| b | T | b | T | b | F | b | T | b | T |

| c | F | c | T | c | T | c | T | c | T |

| d | F | d | F | d | F | d | T | d | F |

| e | F | e | T | e | T | e | T | e | T |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.