Assertive community treatment has been around in one form or another for 25 years. During this time it has become the dominant model of specialist assertive outreach to people with severe mental illnesses. It was developed by pioneering psychiatrists in the USA with the explicit aim of helping patients struggling to stay out of hospital to live more successfully in the community. It achieved this by providing them with more intensive support in obtaining the material necessities of life and by placing a greater emphasis on social functioning and quality of life rather than symptoms. When we published our experiences of setting up an assertive community treatment team in this journal 9 years ago (Reference Kent and BurnsKent & Burns, 1996), only a few teams existed in the UK. Our own team was one of four new services assessed by the UK700 study of intensive case management (Reference Creed, Burns and ButlerCreed et al, 1999). At the time, assertive community treatment was much more widely developed in the USA, where teams were grouped under the catchy title of PACT (Programs in Assertive Community Treatment). This all changed when the National Health Service Plan identified assertive outreach as a necessary component of community mental health provision (Department of Health, 2000). The result has been a very rapid proliferation of assertive community treatment teams in the UK. By April 2004, 270 had been established. In this article, we outline the history of the assertive community treatment model, describe the processes required to run an effective team and the current status of the model as a mental health service intervention in the UK.

Historical development

Training in community living

Assertive community treatment began with the highly influential ‘training in community living’ programme developed during the 1970s at the Mendota Mental Health Institute in Madison, Wisconsin (Reference Marx, Test and SteinMarx et al, 1973). This programme sprang from a recognition by Marx and his colleagues, Stein and Test, that contemporaneous community treatments did little more than maintain chronically disabled patients in ‘a tenuous community adjustment on the brink of rehospitalisation’ (Reference Stein and TestStein & Test, 1980). Their programme was an attempt to address the imbalance of care before and after discharge, and was developed with the understanding that an effective community treatment programme must assume responsibility for helping patients to meet all their needs. These needs, they argued, include the material essentials of life such as food, clothing and shelter; coping skills necessary to meet the demands of community living; motivation to persevere in the face of adversity; freedom from pathologically dependent relationships; and support and education of significant others involved with the patient in the community.

The expectation that socially disabled patients would come to the clinician was replaced with the expectation that the clinician would be assertive in delivering care and go to the patient. The assumption that the patient would negotiate the difficult pathways between different caring agencies was replaced with the assumption that the clinician is responsible for ensuring coordination of inter-agency care. The role of the keyworker became pre-eminent, and key-workers assumed responsibility for delivering a greater proportion of direct care to a much smaller number of allocated patients. Care became needs-led and care programmes were designed for each individual patient.

The results of Stein & Test’s original randomised controlled study of training in community living remain impressive. Over the first year, 58% of the individuals randomised to standard progressive care were readmitted to a psychiatric hospital compared with 6% of those receiving training in community living. Not only were patients on the training in community living programme more likely to live independently in the community but their clinical state improved, together with their social functioning, likelihood of employment, adherence to medication regimens and, most important of all, their quality of life (Reference Stein and TestStein & Test, 1980). These gains were achieved without additional burden on families or other informal carers and (despite the intensity of intervention) at no extra cost because of the saving on beds (Reference Test and SteinTest & Stein, 1980; Reference Weisbrod, Test and SteinWeisbrod et al, 1980). These results have been interpreted to suggest that training in community living was significantly less expensive than standard progressive care. When funding for the programme was withdrawn, all of the gains were lost. This last very important finding indicated that assertive community treatment needs to be offered to patients over the longer term. This led to a change in ethos and a change in name from training in community living to assertive community treatment, reflecting a service providing continuous, longer-term support rather than one-off training.

Assertive community treatment

Assertive community treatment has influenced service development internationally (Reference Marshall and LockwoodMarshall & Lockwood, 1998). This wider influence can be attributed in part to the rigorous manner in which Stein and Test conducted their original study, and in part to successful early replication outside of the USA. One of the most important of these early studies was a replication of training in community living in Sydney, Australia (Reference Hoult, Reynolds and Charbonneau-PowisHoult et al, 1984).

The evidence base for assertive community treatment, although showing some attenuation since the early groundbreaking studies, has remained strong in the USA (Reference Mueser, Bond and DrakeMueser et al, 1998). The same cannot be said of the UK, where evidence for any advantage over standard community mental health team care has not been forthcoming (Reference Holloway and CarsonHolloway & Carson, 1998; Reference Burns, Catty and WattBurns et al, 2002). One possible exception has been the apparent benefit of assertive community treatment for adults with learning disability (Reference Tyrer, Hassiotis and UkoumunneTyrer et al, 1999). The lack of evidence for this treatment approach in the UK was not something we expected when writing in this journal 9 years ago (Reference Kent and BurnsKent & Burns, 1996) and it is something we shall return to later in this article.

The key elements of assertive community treatment

The original US model of assertive community treatment has been well described (Reference Test and LiebermanTest, 1992). A multidisciplinary core services team (continuous treatment team) is responsible for helping its patients meet all of their needs, and does so by being the primary provider of services wherever possible. The team offers continuity of care over time and across traditional service boundaries 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Patients are engaged and followed up assertively, and treatment is offered in the community rather than in traditional service settings. The emphasis is on helping individuals to function as independently as possible, by teaching and enhancing skills in the environment where they will be needed, rather than in day hospitals and sheltered workshops. The patient is assisted in meeting basic needs such as housing, food and work, and the development of a supportive social and family environment. Care plans for each patient are individualised and adaptable to changing needs over time. Goals such as reduced symptom severity, increased community tenure and improved social functioning are explicit. A keyworker from the team is responsible for providing and coordinating the care of each individual, helping the person to manage his or her symptoms on a day-to-day basis and overseeing medication (Box 1).

As we indicated in our previous article (Reference Kent and BurnsKent & Burns, 1996), assertive community treatment is a pure form of clinical case management (Reference KanterKanter, 1989) and lies at the opposite end of the case management continuum to the earlier ‘brokerage’ model (Reference ThornicroftThornicroft, 1991). Many of its underlying concepts have become emblematic of good clinical practice. Individualised, needs-led care planning coordinated by a keyworker is the cornerstone of the care programme approach (Department of Health, 1990).

Box 1 Key elements of the assertive community treatment model

-

• A core services team is responsible for helping individual patients meet all of their needs and provides the bulk of clinical care

-

• Improved patient functioning (in employment, social relations and activities of daily living) is a primary goal

-

• Patients are directly assisted in symptom management

-

• The ratio of trained staff to patients should be small (no greater than 1:15)

-

• Each patient is assigned a keyworker responsible for ensuring comprehensive assessment, care and review by themselves or by the whole team

-

• Treatment plans are individual to each patient and may change over time

-

• Patients are engaged and followed up in an assertive manner

-

• Treatment is provided in community settings because skills learnt in the community can be better applied in the community

-

• Care is continuous both over time and across functional areas

(Adapted from Reference Test and LiebermanTest, 1992)

In the absence of strongly identified ‘critical components’ of assertive community treatment that distinguish it from other community interventions in the UK, it is probably best to talk of indicators of good practice.

Indicators of good practice

Which patients benefit?

In order to determine who assertive community treatment is for we need to consider what it is for (Reference Burns and FirnBurns & Firn, 2002) (Box 2). Stein & Test repeatedly state that its purpose is to maintain regular and frequent contact in order to monitor the clinical condition in order to provide effective treatment and rehabilitation.

Box 2 Features of patients who might benefit from assertive community treatment

Agreed indicators

-

• Psychotic illness

-

• Fluctuating mental state

-

• Fluctuating social functioning

-

• Poor adherence to medication regimens

-

• Poor engagement

-

• Relapse would have severe consequences

Emerging indicators

-

• Belonging to Black or minority ethnic group

-

• Severe bipolar disorder

-

• Borderline learning disability

Accumulated clinical experience suggests that mentally disordered offenders and individuals with a primary diagnosis of personality disorder do not seem to benefit greatly. Although studies of assertive community treatment for forensic populations are ongoing, one study found that intensively managed forensic patients actually spent longer in prison (Reference Solomon and DraineSolomon & Draine, 1995). Rather more unexpectedly, given the target population for assertive community treatment, people with predominantly negative symptoms also seem to gain little. This may well be because of a ceiling effect.

The case manager

Collaborative keyworking remains the dominant approach within assertive community treatment teams, with case managers tending to take a lead role with their allocated patients rather than an exclusive role. This means that, although keyworkers tend to function in a generic role that transcends traditional boundaries of professional expertise, patients get to know more than one member of the team. Consequently they should be less vulnerable to critical dependence on any one individual. It makes staff holidays and sickness easier to negotiate. It also allows staff with specialist skills to enter in and out of the care of a patient as the need arises, in a more natural and seamless way. For example, a team member with an occupational therapy background might be asked to see another key-worker’s patient to discuss vocational opportunities and remain able to cover for the lead keyworker in respect of his or her broader generic role.

There appears to be significant variation in case-loads between assertive community treatment teams in different parts of the UK; the range in London is between 5 and 14 patients per full-time staff member (Reference Wright, Burns and JamesWright et al, 2003). The results of the UK 700 study raise questions about the merit of very low case-loads (Reference Burns, Creed and FahyBurns et al, 1999). Team leaders need to think carefully about where they set their team’s threshold. As a rule of thumb there must be capacity for patients to be seen once or twice a week on a routine basis, with less frequent visiting being the exception. Importantly, teams need to retain the capacity to work very intensively with individuals when the need arises, for example, to avoid hospital admission. A well-functioning assertive community treatment team should be able to visit patients with high needs for care on a daily basis and sustain this level of involvement for several weeks (Reference Burns and FirnBurns & Firn, 2002). From a purely practical perspective, case-loads greater than 15 are unlikely to allow this.

The team

Traditional assertive community treatment teams emphasise a team approach to case management, with all members getting to know all patients and pooling responsibility for their care. The aim is to avoid an ‘overinvolved’ one-to-one relationship that might lead to pathological dependency.

Advantages to a team approach include the dilution of stress by sharing anxiety during crises and the prevention of the emotional burnout associated with close one-to-one work with resentful or treatment-resistant individuals. In practice, teams manage large numbers of patients and members cannot be expected to know every single one well enough to step into the case management role, with adequate knowledge of relapse signatures, risk indicators and social networks. Engaging individuals in treatment is also more difficult if they have to deal with many staff rather than a few. Teams usually need to adopt a pragmatic approach, using the blend of team- and keyworking that best suits each individual patient. For example, some individuals successfully engage with only one or two members, whereas others get to know all of the team over time.

Skills mix

Assertive community treatment teams need to maintain the same broad mix of skills as traditional community mental health teams. Arguably the range of skills is even more important, as one of the guiding principles of assertive community treatment is that the team should provide as much direct care as possible and avoid referring externally. The importance of this is illustrated by the frequent need to work with individuals with dual diagnosis. For this reason, teams really benefit if they have someone skilled in the assessment and management of substance misuse.

Gaps in a team’s skills mix can be addressed with training. Skills in cognitive–behavioural therapy, compliance counselling and motivational interviewing, for example, can be acquired by all mental health professionals. Indeed, the value of these therapies in engaging and treating people with enduring psychotic illnesses, together with their emphasis on a collaborative and non-confrontational approach, make them important skills for all clinical case managers in assertive community treatment teams.

Assertive community treatment requires staff not only to develop new skills, but also to adopt new ways of working. It demands a lot of individual case managers, whatever their professional background, as they are continuously expected to work beyond traditional professional boundaries and develop at least a minimal competence across a range of areas. These competencies include stabilising the patient’s living situation, monitoring medication and ensuring adherence, crisis resolution, and training and supporting the individual in activities of daily living in their own environment (Reference Burns and FirnBurns & Firn, 2002). When the team contains a good mix of different professionals, there is much to be said for regular interprofessional training. This approach is not only cost-effective, but it also promotes team-building and helps highlight gaps in a team’s skills mix. Where there are gaps, training from external agencies can be sought.

As with all mental health teams, a real value of a diverse mix of professionals working closely together is the breadth and depth of expertise that can be brought to bear on a problem. The different perspectives and philosophies that come with a social work or nursing background, for example, can add enormously to discussions about patient management.

In the future, non-professionally qualified support workers may have a more prominent role within UK assertive community treatment teams. Indeed, there may be real advantages in employing ‘fresh’ staff unconstrained by any one professional tradition. Experience suggests that they can be very effective at engaging patients, especially when they themselves have had experience of mental health problems. ‘User-workers’ are particularly common in US teams.

Key areas of expertise that should be available within an assertive community treatment team are summarised in Box 3.

Box 3 Key areas of expertise

-

• Diagnosing and managing substance misuse

-

• Motivational interviewing

-

• Cognitive–behavioural therapy

-

• Family therapy

-

• Administering and monitoring medication in the community

-

• Assessing medication side-effects

-

• Vocational assessment and rehabilitation

-

• Life planning

-

• Assessing activities of daily living

Team schedule

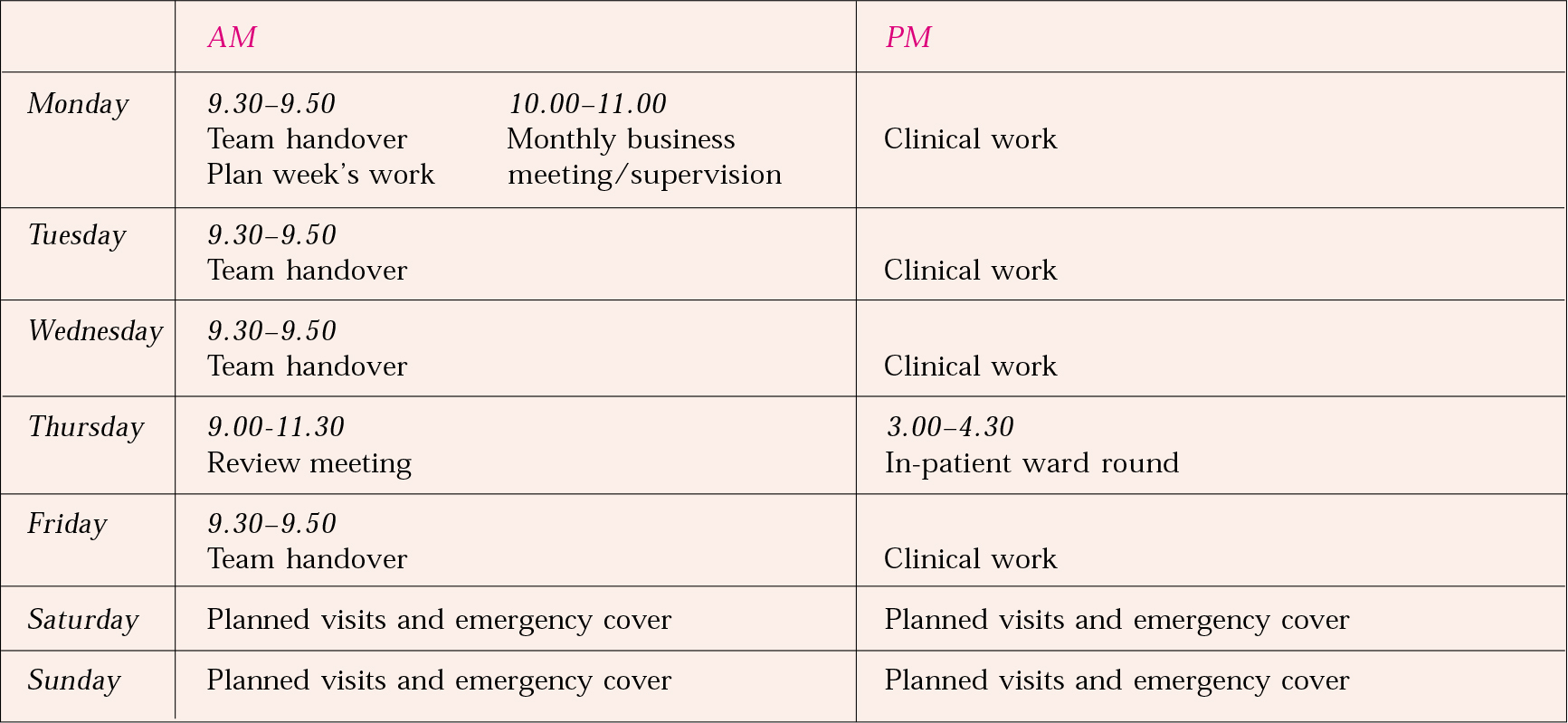

The team needs to meet once a day for a brief hand-over meeting, which should ideally last less than half an hour (Fig. 1). This is an opportunity to discuss current or emerging problems and to allocate tasks, not to conduct in-depth reviews. These should wait until the team’s weekly care plan review meeting. At handover meetings, each case manager should quickly run through all of his or her patients, flagging any concerns. Care should be taken also to look at the cases allocated to any team member who is absent or on leave. Monday handovers should include planning of the week’s work and Friday handovers discussion of problems that might arise over the weekend.

Fig. 1 Example timetable.

Weekly review meetings are an opportunity for a more in-depth review of cases (a statutory requirement in England for all patients with mental illness and complex needs). The frequency of review will depend on the patient’s need and the team’s overall case-load, but reviews should be systematic and include a summary by the case manager and risk and needs assessments. Some teams use structured clinical assessment scales to facilitate objective progress monitoring; regular contact with a patient can make it hard to spot gradual changes.

Team size

There are no hard and fast rules about the number of members in an assertive community treatment team. Experience indicates that a team needs to be large enough to maintain the right skills mix when key-workers are on leave. If too large, a team becomes unwieldy and excessive time is spent on communication. A team of 10–12 professionals seems to work well (Reference Burns and FirnBurns & Firn, 2002).

Patterns of care

Hours of availability

Expectations that teams will provide around-the-clock, direct-access crisis intervention derive from early descriptions of the assertive community treatment model. Closer scrutiny suggests that, for some teams at least, this was made possible by staff who were available from home on an on-call basis rather than from a ‘mobile’ crisis team working through the night. Whether they are at home or in an office, the idea of staff being immediately available at any hour is understandably attractive to service users, carers and commissioners. It certainly sits well with the notion of care that is continuous both over time and across functional areas. Increasingly, however, the need for assertive community treatment teams to provide any form of direct 24-hour care is questioned and very few offer it.

Most mature assertive community treatment services operate for extended hours, but few run throughout the night. There are good reasons for this. Operating a team safely for 24 hours a day is extremely expensive, both in financial terms and in terms of staff opportunity cost. Staff morale is inevitably more difficult to sustain if team members are required to work complex shift patterns with extended periods of relative inactivity. Professionals attracted to the assertive community treatment model enjoy intensive contact with patients. Importantly, the argument for 24-hour care has not been supported by any convincing evidence that patients make significant use of it. The mark of a mature and well-functioning assertive community treatment team, effective at identifying risk indicators and relapse signatures, should arguably be the absence of much late-night need. Finally, few other services operate overnight, significantly limiting the scope for any effective care coordination.

The argument for extended hours and weekend cover is much stronger. A few teams operate for extended hours (usually from 08.00 h to 20.00 h) on a shift system (usually morning and evening with an afternoon overlap). The daily handover meeting can then take place between shifts rather than at the beginning of the day. Evening work offers more opportunities to work with families and other informal carers, and many patients understandably prefer to take potentially sedating medication at night. The problems with the shift system are manifest in the complexity of information exchange and the difficulties of keeping a critical mass of staff on duty at any time. Increasingly, assertive community treatment teams in the UK work predominantly ‘office hours’, with individual flexibility. Given the parallel rise of crisis resolution/home treatment teams this seems eminently sensible.

Hospitalisations

A continuous and seamless assertive community treatment service should ideally manage individuals throughout their hospital admissions, exerting full control over the timing of admission and discharge. In many locations, different teams look after patients in the community and patients in hospital. In these circumstances, assertive community treatment teams can provide a continuity that is not otherwise available. In reality, many such teams in the UK have to relinquish responsibility for in-patient care. In such circumstances, close liaison with the in-patient team is essential if continuity of care and opportunities for early discharge are to be maintained. Active ‘inreach’ (visiting individuals while in hospital at least as often as one would visit them in the community) is an essential aspect of assertive community treatment work.

The role of the psychiatrist

Not all assertive community treatment teams include psychiatrists. Some liaise with psychiatrists outside of the team in adjacent local services. A recent survey of expert opinion (Reference Burns, Knapp and CattyBurns et al, 2001) revealed a high agreement that medical involvement is a crucial component of assertive community treatment and this seems to have been confirmed by cluster analysis (see ‘The control condition’ below).

Assertive community treatment teams are not especially hierarchical and it is accepted that team members of all disciplines can take responsibility for decision-making about patients. This concept is more readily accepted in some countries and cultures than others. The relative scarcity of psychiatrists in the UK, for example, has meant that nurses are used to taking on extensive responsibility for patients. Teams working regularly with a psychiatrist appreciate the opportunity to get early medical reviews if there are problems. On the whole, prescribing medication remains the responsibility of doctors and clearly some decisions require senior psychiatric involvement.

Engagement with treatment

Assertive community treatment teams have always recognised the importance of promoting treatment adherence. The effective engagement of patients with medication regimens seems likely to have made a very significant contribution to the early success of the model. The increasing use of clozapine in the community has introduced another dimension to the work of assertive community treatment teams, as the task of promoting clozapine is especially suited to an intense and assertive outreach approach. They have a real opportunity to provide an effective intervention for individuals who might otherwise be unable to receive it. Clozapine can be delivered daily to promote adherence, and case managers are well placed either to take patients to a clinic for blood tests or even to carry them out in the patients’ homes. One team has described starting clozapine at home to avoid the need for admission (Reference O'Brien and FirnO’Brien & Firn, 2002), and the drug data sheet has been amended accordingly.

Referral to and discharge from a team

Assertive community treatment is expensive and should be reserved for people who cannot be managed effectively by routine services. Typically, these individuals will have a psychotic illness with fluctuating mental state and social functioning and poor adherence to prescribed medication. Acceptance criteria need to be clear and transparent to avoid confusion among referrers. The most likely criteria are listed in Box 4. Research is still needed to determine who is most suitably helped by assertive community treatment, but the quality of other local services will probably be a factor governing referral thresholds.

Box 4 Key criteria for referral to an assertive community treatment team

-

• Severe mental illness

-

• Heavy use of services

-

• Several admissions to hospital within the previous few years

Although Reference Stein and TestStein & Test (1980) moved away from a time-limited intervention, lifelong assertive community treatment is neither necessary nor practical when there are good alternative services. Transferring patients back to routine services should happen in a planned way, after a long period of reduction in clinical input from the assertive community treatment team to test stability and allow an adequate handover period. If the transition to the standard service fails there should be flexibility within the system for the individual to be referred back to the assertive community treatment team.

A small minority of patients fail to engage with any team. There are no hard and fast rules about how long an assertive community treatment team should attempt to engage such individuals, but sometimes the team has to accept that it will not succeed. By the same token, the lack of proven success for assertive community treatment with individuals who have predominantly negative symptoms means that the team needs to carefully weigh the possibility of small to insignificant gains against a large amount of time and clinical effort. Discharging patients who have consistently failed to benefit will allow a degree of ‘throughput’ – freeing places for individuals who may experience much greater gains.

Current status of assertive community treatment in the UK

As indicated, early optimism about the benefits of assertive community treatment in the UK has not been matched by reality. The studies that have been conducted have failed to demonstrate the hoped for improvements in long-term outcome, with reduced bed occupancy a primary measure (Reference Ford, Ryan and BeadsmooreFord et al, 1997; Reference Holloway and CarsonHolloway & Carson, 1998; Reference Wykes, Leese and TaylorWykes et al, 1998; Reference Burns, Creed and FahyBurns et al, 1999). There has been no convincing evidence that assertive community treatment is better than pre-existing UK community mental health services at improving clinical symptoms, social functioning or quality of life. The lack of any impact on bed occupancy has meant that there has been no demonstrable economic benefit either (Reference Byford, Fiander and TorgersonByford et al, 2000). Given the comparable performance of the less expensive community mental health teams in UK studies, there are inevitable issues regarding the introduction of assertive community treatment services nationwide. The cautions voiced about the costs and benefits of assertive community treatment in the commentary accompanying our first article seem even wiser with hindsight (Reference HirschHirsch, 1996).

The key challenges, then, are to seek to understand the UK results in a way that helps us improve our services across the board and to manage assertive community treatment teams in their local context in a creative way that ensures delivery of the very best for their patients.

Explaining the UK results

Three factors need to be considered to understand the results of the UK studies: model fidelity, context and the control condition.

Model fidelity

Much attention has been paid to the question of model fidelity – the extent to which a team describing itself as an assertive community treatment team matches the accepted definition of such a team. The question is complicated by our poor understanding of which of the described components actually matter. Attempts to operationalise the critical components of assertive community treatment have been largely self-referential, with ‘experts’ already convinced that the model works being asked what they think is most important (Reference McGrew and BondMcGrew & Bond, 1995). A striking example is small staff case-load. Case-loads of fewer than 12 are strongly promoted as a critical component of assertive community treatment. Few would have predicted that reducing UK care coordinators’ case-loads by more than two and a half times (comparing average case-loads of 32 for standard care with 12 for assertive community treatment) would not lead to any significant differences in outcome on any measured variable at 2 years, yet this is exactly what the largest UK randomised controlled trial found (Reference Burns, Creed and FahyBurns et al, 1999). Not only was this result unexpected given the preoccupation with case-loads that we all share, but it is also counter-intuitive, unless one postulates some kind of ceiling effect. It also suggests that we should not blindly accept that any other single ingredient of assertive community treatment is critical to its success. How important, for example, is ‘assertiveness’?

Although it is important that we refine our understanding of which components are important for success, recent research indicates that some UK assertive community treatment services, although differing in some aspects of practice, are not significantly different from benchmark American counterparts (Reference Fiander, Burns and McHugoFiander et al, 2003).

Context

In the USA, Stein & Test’s service was introduced against the backdrop of a large, isolated mental hospital surrounded by office-based private practitioners. The UK comparison services were far more integrated and continuous, and they had already adopted the care management model that had made the first assertive community treatment services so innovative. This raises the interesting question of whether comparative UK community mental health services, integrated as they are with well-functioning primary care and social services, have been so effective for patients with severe mental illness that American-sized differences in outcome between assertive community treatment and ‘standard care’ are unlikely.

The control condition

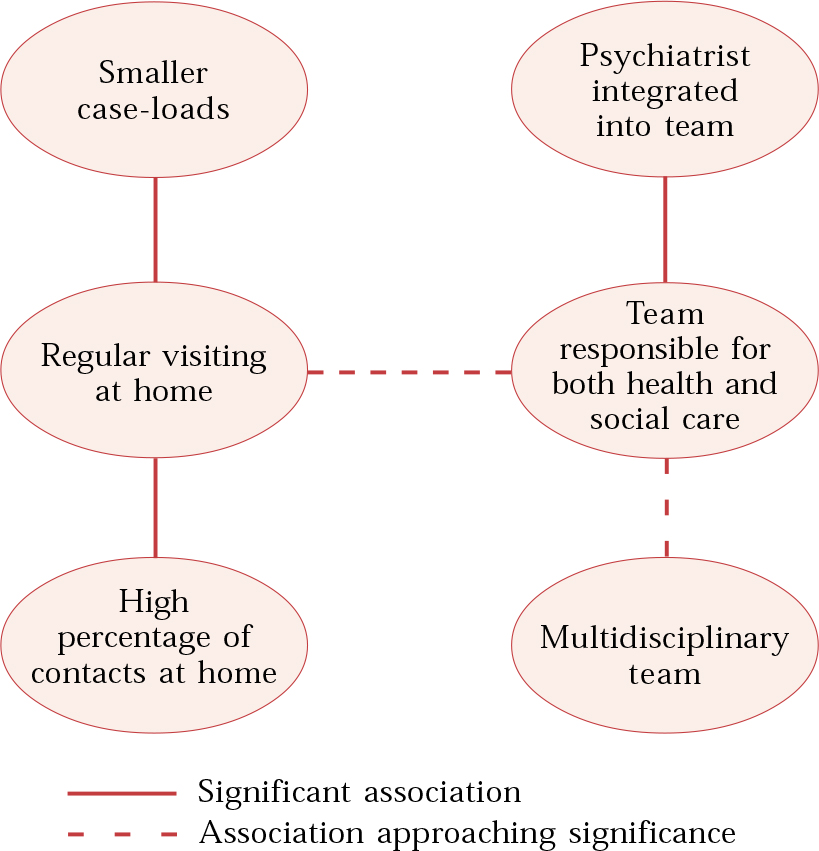

The third factor in the studies, and one that raises much broader questions, is the control condition. Services change over time and have always varied with location. It is possible that UK studies (as with later US and Australian studies) have failed to find differences because the control-condition standard services already contain the main effective ingredients of assertive community treatment. There is some strong evidence for this (Reference Burns, Knapp and CattyBurns et al, 2001, Reference Burns, Catty and Watt2002; Reference Wright, Catty and WattWright et al, 2004). In particular, in a review of international home-based care, Reference Burns, Catty and WattBurns et al (2002) performed cluster analysis on data about actual practice obtained from the researchers who had conducted over 60 of the 91 trials that their review examined. This identified the regular clinical features of the experimental services and the authors then used regression analysis to test individual features against reduction in bed occupancy. This produced six features common to the various treatment models and two that were positively associated with reduced bed occupancy (Fig. 2). Clearly several of these are found in routine UK care and may explain, in part, the failure of studies to demonstrate substantial advantages of assertive community treatment.

Fig. 2 Intercorrelations between service components.

Or is there no case to answer?

Although any of these three explanations may hold the key it is also possible that there is no question to answer. A detailed comparison of the in-patient component of home-based care in US and UK studies (predominantly of assertive community treatment) found that the main difference was that US control patients spent more time in hospital, whereas experimental patients in both countries spent about the same time in both locations (Reference Burns, Catty and WattBurns et al, 2002). So it is still far from clear that US assertive community treatment services are that much more effective than equivalent UK services.

Despite these reservations, until we have a better understanding of the ingredients and contextual factors required for optimal assertive community treatment, the challenge for anyone running a team in the UK is not to try to replicate the American model exactly, but rather to take a local view and consider each aspect of the model an indicator of good practice. For example, geographically dispersed rural teams may have to adopt practices different from those of inner-city teams. The high quality of UK community mental health services also raises the possibility of discharging patients from assertive community treatment teams, something that seems at odds with early views on the long-term (possibly lifelong) supporting function of the model.

Conclusions

Assertive community treatment is the most widespread and durable model of clinical case management for the treatment and rehabilitation of people with severe and enduring mental health problems. It is established in the USA, where it has been repeatedly shown to have significant advantages over routine care, and it is increasingly being adopted in the UK and mainland Europe. Although the same advantages have not been demonstrated outside of the USA, allocation of new funding to assertive community treatment in the UK has effectively ring-fenced resources for the care of some of the patients with the greatest needs.

Assertive community treatment should be an addition to well-organised and appropriately resourced routine services; it should not be a replacement. It should be restricted to individuals with psychosis and complex needs, utilising evidence-based interventions wherever possible and applying indicators of good practice to local circumstances. Research continues into what the effective elements of assertive community treatment are and into how to target the most appropriate patients to benefit from this form of care.

MCQs

-

1 Assertive community treatment incorporates the following key elements:

-

a engagement and follow-up of patients in an assertive manner

-

b improved symptom management as the primary goal

-

c continuous care both over time and across functional areas

-

d training the patient to avoid seeking help with symptom management

-

e avoidance of the use of medication to treat symptoms.

-

-

2 The following problems are agreed indicators for assertive community treatment:

-

a neurotic disorder

-

b severe learning disability

-

c personality disorder

-

d fluctuating social functioning

-

e psychotic disorder.

-

-

3 Assertive community treatment has been shown to be:

-

a more effective than standard care in the UK

-

b the treatment of choice for patients with bipolar mood disorder

-

c less expensive than standard care in the UK

-

d a good alternative to day hospitalization

-

e more effective at reducing symptoms than at reducing functioning.

-

-

4 Assertive community treatment teams should avoid:

-

a managing patients during in-patient admissions

-

b prescribing medication

-

c pathological dependency

-

d sharing their anxiety during a crisis

-

e requiring case managers to work within professional boundaries.

-

-

5 Assertive community treatment:

-

a developed from training in community living

-

b aims to help patients live independently

-

c aims to replace the total support of hospital with comprehensive support in the community

-

d avoids the use of psychological therapies

-

e is the most rigorously evaluated model of psychiatric community care.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | T | a | F | a | F | a | F | a | T |

| b | F | b | F | b | F | b | F | b | T |

| c | T | c | F | c | F | c | T | c | T |

| d | F | d | T | d | F | d | F | d | F |

| e | F | e | T | e | F | e | T | e | T |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.