Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects 3–7% of children (Reference WilensWilens 2004). Prospective longitudinal studies show persistence of the disorder in 10–20% of adults diagnosed with ADHD in childhood, and a further 40–60% of patients experience partial remission, with persistence of some symptoms and significant clinical impairments (Reference Barkley, Murphy and FischerBarkley 2008). Population studies estimate the prevalence of adult ADHD at between 3.4 and 4.4% (Reference Kessler, Adler and BarkleyKessler 2006). The DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994) and the ICD-10 (World Health Organization 1993) criteria are widely used to diagnose ADHD in adults. The 2008 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines provide evidence for the validity of ADHD diagnosis in children and adults and make recommendations for its diagnosis and management. Detailed description of clinical diagnosis and management of adult ADHD is given elsewhere (Reference Weiss and MurrayWeiss 2003).

Substance use disorders are common in adults with ADHD (Reference Kessler, Adler and BarkleyKessler 2006; Box 1). Prospective studies (Reference Molina and PelhamMolina 2003) and population-based surveys (Reference Kessler, Adler and BarkleyKessler 2006) clearly demonstrate a higher prevalence of substance use disorder in individuals with ADHD. Likewise, the prevalence of ADHD is substantially higher in adolescents and adults seeking treatment for substance use disorder (Reference Schubiner, Tzelepis and MilbergerSchubiner 2000).

BOX 1 Main clinical issues of ADHD comorbid with substance misuse

-

• Substance use disorders are a frequent comorbidity in ADHD

-

• Significant challenges exist in assessing and treating ADHD in the context of substance use disorder comorbidity

-

• No clear treatment guidelines and care pathways exist to guide clinicians to manage ADHD with comorbid substance use disorder

-

• Issues in relation to exacerbation of substance use disorder, future risk of substance misuse and diversion of psychostimulants complicate treatment

Methodology

This review discusses the relationship between substance use disorder and adult ADHD. We performed a comprehensive search of Medline and PsycINFO databases using the search terms ‘attention deficit hyperactivity disorder’, ‘substance related disorder’, ‘substance misuse’ and ‘street drugs’ and checked the reference lists of identified articles. We also searched the internet using Google, as well as searching psychiatry textbooks, published and unpublished treatment guidelines and conference proceedings by hand. To improve the clinical relevance we considered use of both licit and illicit substances, including nicotine, alcohol, cocaine and cannabis. The studies reviewed in our article used standardised criteria from DSM-III, DSM-III-TR, DSM-IV or ICD-10 (American Psychiatric Association 1980, 1987, 1994; World Health Organization 1993) to diagnose adolescents or adults with ADHD and comorbid substance use disorder.

Relationship between substance use disorder and ADHD

Several longitudinal studies of children and adolescents with ADHD point to a greater risk of developing substance use disorder in adolescence and adulthood as compared with matched controls (Reference Molina and PelhamMolina 2003; Reference Biederman, Monuteaux and MickBiederman 2006). Factors such as high novelty seeking trait, self-medication for ADHD symptoms (Reference AshersonAsherson 2005) and comorbid disorders such as conduct disorder (Reference Milberger, Biederman and FaraoneMilberger 1997; Reference Molina and PelhamMolina 2003) and bipolar disorder (Reference Biederman, Wilens and MickBiederman 1997) increase the risk of developing substance use disorder in people with ADHD (Box 2).

BOX 2 Relationship between ADHD and substance use disorder

-

• ADHD greatly elevates risk for substance use and misuse

-

• High novelty seeking trait, self-medication for ADHD symptoms and the presence of conduct disorder and bipolar disorder are risk factors for substance misuse in adult ADHD

-

• Patients with ADHD and substance use disorder tend to commence early and experiment more freely with substance misuse

-

• Growing up with ADHD confers a greater risk for using alcohol and tobacco, whereas clinic-referred adults with ADHD seem more likely to use marijuana, cocaine and LSD

-

• Substance use may be considered as a form of self-medication for patients with ADHD

Patients with ADHD and substance use disorders tend to commence early and experiment more freely with substance misuse compared with patients with substance use disorder without ADHD (Reference Krause, Dresel and KrauseKrause 2002a). Two recent studies, the UMASS project and Milwaukee study (Reference Barkley, Murphy and FischerBarkley 2008) demonstrate important findings. Compared with matched controls, adults with ADHD were more likely to be past or current users of substances and used these substances in greater amounts. They were also more likely to receive treatment for previous alcohol and drug use disorders. The UMASS project and the Milwaukee study further demonstrate that children growing up with ADHD may carry a greater risk for using alcohol and tobacco, while clinic-referred adults with ADHD seem more likely to use marijuana, cocaine and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD).

Substances most commonly used by adults with ADHD (Box 3)

BOX 3 ADHD and substance use

-

• Studies in both adults and adolescents have found ADHD to be associated with earlier initiation and higher rates of lifetime substance use (nicotine 41–42%, alcohol 33–44%, cocaine 10–35%, cannabis 51%, opiates 16–19%)

-

• ADHD has been shown to be an independent risk factor for tobacco use specifically in clinical and high-risk samples, even after controlling for comorbid conduct disorder

-

• Substance use in ADHD may be considered as a form of self-medication for patients with ADHD. Clinical observations have revealed that patients with ADHD with substance use disorder often demonstrate an improvement of ADHD symptoms

-

• Given that some substances have been shown to reduce ADHD symptoms, abstinence may be more difficult for adults with ADHD

Nicotine

Studies in both adults and adolescents have found ADHD to be associated with earlier initiation of regular cigarette smoking and higher rates of lifetime smoking (41–42% v. 26% for ADHD and non-ADHD respectively) (Reference Pomerleau, Downey and StelsonPomerleau 1995). Significant associations between ADHD symptoms and cigarette smoking have been found in both general population (Reference Kollins, McClernon and FuemmelerKollins 2005) and longitudinal studies (Reference Milberger, Biederman and FaraoneMilberger 1997; Reference Molina and PelhamMolina 2003). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder has been shown to be an independent risk factor for tobacco use specifically in clinical and high-risk samples, even after controlling for comorbid conduct disorder (Reference Milberger, Biederman and FaraoneMilberger 1997; Reference Molina and PelhamMolina 2003).Reference Milberger, Biederman and FaraoneMilberger et al (1997) followed 6- to 17-year-olds with and without ADHD for 4 years and found that ADHD was specifically associated with a higher risk of initiating cigarette smoking even when controlling for social class, psychiatric comorbidity and intelligence.

Factors such as inattention and deficits in executive functioning (Reference Molina and PelhamMolina 2003), hyperactive/impulsive symptoms (Reference Fuemmeler, Kollins and McClernonFuemmeler 2007), novelty-seeking traits (Reference Tercyak and Audrain-McGovernTercyak 2003) and dysregulation of dopaminergic/nicotinic and acetylcholinergic circuits have been proposed to explain ADHD–smoking comorbidity. Two literature reviews (Reference McClernon, Kollins and LutzMcClernon 2008; Reference Glass and FloryGlass 2010) provide evidence for the importance of cognitive, social, psychobiological and genetic factors in understanding the association between ADHD and cigarette smoking.

Clinical observations have revealed improvement of attention, concentration and impulse control with nicotine (Reference Gehricke, Whalen and JamnerGehricke 2006) and several lines of evidence suggest that nicotine may be useful in treating ADHD symptoms (Reference Newhouse, Potter and BucciNewhouse 2008).

Given that nicotine has been shown to reduce ADHD symptoms, smoking cessation may be more difficult for adults with ADHD (Reference Pomerleau, Downey and SnedecorPomerleau 2003). A controlled laboratory study demonstrated that nicotine abstinence among smokers with ADHD is associated with greater worsening of attention and response inhibition than among those without ADHD (Reference McClernon, Kollins and LutzMcClernon 2008). In another study of over 400 adult participants in smoking cessation treatment studies, childhood ADHD diagnosis was significantly associated with treatment failure (Reference Humfleet, Prochaska and MengisHumfleet 2005).

Alcohol

Several studies have documented a high incidence (33–44%) of alcohol misuse or dependence in adults with ADHD (Reference Biederman, Wilens and MickBiederman 1998; Reference Rasmussen and GilbergRasmussen 2000). Likewise, an increased prevalence of childhood and persistent ADHD is noted in alcohol-dependent adults (Reference Krause, Biermann and KrauseKrause 2002b).

However, it is uncertain whether ADHD predicts the development of alcohol use disorders. A Danish longitudinal study (Reference Knop, Penick and NickelKnop 2009) designed to identify antecedent predictors of adult male alcoholism selected 223 sons of alcoholic fathers and 106 matched sons of non-alcoholic fathers from a Danish cohort (n = 9125). The study showed that: paternal risk did not predict adult alcohol dependence; ADHD comorbid with conduct disorder was the strongest predictor of later alcohol dependence; and that each measure (ADHD and conduct disorder) independently predicted a measure of lifetime alcoholism severity. Other long-term follow-up studies conducted in adolescents and young adults, however, have found no increased risk for alcohol use disorders in individuals with ADHD (Reference Molina and PelhamMolina 2003) or revealed mixed findings. In a longitudinal study, Reference Molina, Flory and HinshawMolina et al (2007) found that childhood ADHD predicts heavy drinking, symptoms of alcohol use disorders, and alcohol use disorders for 15- to 17-year-olds, but not 11- to 14-year-olds or 18- to 25-year-olds.

Cocaine

Studies have reported prevalence rates of 10–35% of childhood ADHD in treatment-seeking cocaine users (Reference Carroll and RounsavilleCarroll 1993; Reference Levin, Evans and KleberLevin 1998). Cocaine users who had childhood ADHD are younger at presentation for treatment and report more severe substance use, more frequent and intense cocaine use, and intranasal or intravenous use of cocaine (Reference Carroll and RounsavilleCaroll 1993). In the UMMAS study of clinic-referred adults (Reference Barkley, Murphy and FischerBarkley 2008), cocaine use was specifically associated with ADHD. The study revealed that the risk for cocaine use was related to higher ADHD symptoms, lower IQ and greater criminal diversity scores. Clinical observations have revealed that patients with ADHD and comorbid cocaine addiction often show an improvement of ADHD symptoms. The ‘self-treatment’ hypothesis is supported by studies reporting marked reduction in ADHD symptoms after cocaine consumption (Reference Volkow and SwansonVolkow 2003). Pathophysiologically, this may be explained by the dopaminergic action of cocaine reducing the core symptoms of ADHD.

Cannabis

Reference Torgersen, Gjervan and RasmussenTorgersen et al (2006) reported lifetime and current rates of cannabis misuse of 51% and 36% respectively for their sample of 45 adults with ADHD. Reference Molina, Flory and HinshawMolina and colleagues (2007) described an analysis of the Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD at the 24- and 36-month time points comparing individuals with ADHD with a control group without ADHD. At both the 24- and 36-month time point the group with ADHD was found to have significantly higher rates of cannabis use along with nicotine and alcohol (ADHD: 3.0%; no ADHD: 0%). A 25-year prospective longitudinal study of a birth cohort of New Zealand children (n = 1265) showed a significant association between cannabis use and increasing self-reported symptoms of adult ADHD at age 25 (Reference Fergusson and BodenFergusson 2008).

Few studies have examined the relationship between cannabis use and ADHD. Reference Adriani, Caprioli and GranstremAdriani et al (2003) gave evidence that cannabinoid agonists reduce hyperactivity in a spontaneously hypertensive rat strain, which is regarded as a validated animal model for ADHD. Reference Aharonovich, Garawi and BisagaAharonovich and colleagues (2006) found significantly better treatment retention of cocaine-dependent patients with comorbid ADHD among moderate users of cannabis compared with abstainers or heavy users. The relationship between cannabis use and ADHD remains unclear and more empirical work is required to understand mechanisms determining this comorbidity.

Opioids

There are very few studies examining the relationship between ADHD and opioid use disorder. Existing data from retrospective and prospective studies, however, suggest high rates of ADHD (16–19%) in treatment-seeking chronic opioid users (Reference King, Brooner and KidorfKing 1999; Reference Torgersen, Gjervan and RasmussenTorgersen 2006).

Caffeine

Caffeine is a popular psychostimulant consumed in most parts of the world. Clinical observations reveal increased consumption of caffeine in the ADHD population. Adults presenting with ADHD tend to give an account of regular and increased consumption of caffeine through beverages such as tea, coffee, coke and energy drinks with high caffeine content. Caffeine in moderate amounts produces increased alertness and elevated mood (Reference Cox, Jacob and LeblancCox 1983). In a literature review, Reference Ross and RossRoss & Ross (1982) concluded that caffeine may be a viable treatment alternative for ADHD when other drugs must be discontinued due to side-effects. Reference Ross and RossRoss & Ross (1982) also estimated a therapeutic dose of caffeine in children to be between 100 and 150 mg of caffeine, equivalent to 6 mg of dextroamphetamine. However, the relationship between caffeine and ADHD remains unclear and further studies are warranted to elucidate patterns of use and efficacy of caffeine in controlling ADHD symptoms.

Treatment studies in ADHD with substance use disorder

Psychostimulants

Methylphenidate

Several meta-analyses of randomised clinical trials (Reference Koesters, Becker and KilianKoesters 2009; Reference Faraone and GlattFaraone 2010) and evidence-based guidelines suggest that stimulants should be the first option for treatment for adult ADHD (Reference Nutt, Fone and AshersonNutt 2007; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2008). However, most ADHD treatment studies typically exclude individuals with substance use disorder and it would be difficult to extrapolate evidence derived from these studies to this population with a dual diagnosis of ADHD and substance use disorder (Reference Szobot and BuksteinSzobot 2008). Reference Koesters, Becker and KilianKoesters and colleagues (2009) performed a meta-analysis of clinical trials comparing methyl-phenidate with placebo in adult ADHD. In a subgroup analysis, four randomised controlled double-blind studies were identified that addressed the efficacy of methylphenidate in adults with ADHD and comorbid substance use disorders (Table 1). Three studies had a parallel group design (Reference Schubiner, Saules and ArfkenSchubiner 2002; Reference Levin, Evans and BrooksLevin 2006, Reference Levin, Evans and Brooks2007) and one study (Reference Carpentier, De Jong and DijkstraCarpentier 2005) used a cross-over design. There was large variability of treatment duration (2–14 weeks) and mean daily dose (34–79 mg). The meta-analysis of ADHD with substance use disorder studies (Reference Koesters, Becker and KilianKoesters 2009) yielded an overall effect size of near zero (0.08; 95% CI –0.20 to 0.35). All four studies demonstrated no significant difference in ADHD or substance use symptoms with methylphenidate compared with placebo, although in one study (Reference Schubiner, Saules and ArfkenSchubiner 2002) physician and self-ratings taken at various times showed significant improvement in some ADHD symptoms in the methylphenidate group. Another study (Reference Levin, Evans and BrooksLevin 2007) reported a significant decrease in the probability of cocaine-positive urine samples with methylphenidate compared with placebo. All four studies recruited their study samples from treatment centres, so the results may not be representative of the general population (Royal Australasian College of Physicians 2009). None of the studies found serious adverse events as a result of the treatment, nor did the substance use disorder worsen because of the use of a stimulant (Royal Australasian College of Physicians 2009).

TABLE 1 Treatment studies for stimulants/non-stimulants in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) comorbid with substance use disorders

Amphetamines

Randomised placebo-controlled trials demonstrate superior efficacy of amphetamines in adults with ADHD (Reference Torgersen, Gjervan and RasmussenTorgersen 2008) and in treatment of cocaine dependence (Reference Grabowski, Rhoades and StottsGrabowski 2004a). Our literature search did not find any studies evaluating the efficacy of amphetamines in ADHD with substance use disorder.

Pemoline

Pemoline is a psychostimulant that acts through dopamine mechanisms. Reference Riggs, Hall and Mikulich-GilbertsonRiggs et al (2004) conducted a 12-week randomised controlled trial (RCT) to study the efficacy of pemoline in adolescents with ADHD and comorbid conduct disorder and substance use disorder (Table 1). The study found a significant difference in ADHD symptoms with pemoline treatment compared with placebo. However, despite efficacy for ADHD, pemoline did not have an impact on substance use disorder or conduct disorder. Pemoline is no longer commonly used in treatment of ADHD because of its association with liver toxicity.

Modafinil

Modafinil is an analeptic drug approved for the treatment of narcolepsy, shift work sleep disorder and excessive daytime sleepiness associated with obstructive sleep apnoea. Modafinil, like other stimulants, increases the release of monoamines, specifically the catecholamines noradrenaline and dopamine, from the synaptic terminals. Modafinil has demonstrated dose-related positive effects in reducing impulsive responding in normal volunteers and in patients with ADHD (Reference Turner, Clark and DowsonTurner 2004). A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 62 cocaine-dependent men and women reported increased cocaine abstinence in the modafinil group (Reference Dackis, Kampman and LynchDackis 2005). Our literature search, however, did not reveal any studies specifically evaluating modafinil in ADHD with substance use disorder.

Non-stimulants

Atomoxetine

Atomoxetine is a highly specific noradrenergic reuptake inhibitor with no misuse liability (Reference Heil, Holmes and BickelHeil 2002). Its efficacy in ADHD is clearly demonstrated in two 10-week double-blind, randomised controlled studies in adults (n = 536) with ADHD (Reference Michelson, Adler and SpencerMichelson 2003). However, studies addressing efficacy of atomoxetine in patients with ADHD and comorbid substance use disorders are very limited (Table 1). A 3-month double-blind, placebo-controlled study of atomoxetine in adults with ADHD and comorbid alcohol use disorder found clinically significant improvement in ADHD symptoms but inconsistent effects on drinking (Reference Wilens, Adler and WeissWilens 2008a). Reference Thurstone, Riggs and Salomonsen-SautelThurstone et al (2010) explored the impact of atomoxetine on substance use in an RCT involving 70 adolescents with ADHD. Participants received atomoxetine and cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) or placebo and CBT. Although the group receiving atomoxetine and CBT showed an improvement in scores on the DSM-IV ADHD checklist, this was not statistically significant compared with the placebo group.

Atomoxetine has also gained attention in the treatment of nicotine withdrawal. Reference Ray, Rukstalis and JepsonRay et al (2009) studied the effects of atomoxetine on subjective and neurocognitive symptoms of nicotine abstinence. The drug was reported to reduce subjective nicotine withdrawal symptoms and self-reported smoking urges.

Bupropion

Bupropion is an atypical antidepressant that acts as a noradrenaline and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, and nicotinic antagonist (Reference Slemmer, Martin and DamajSlemmer 2000). It is considered safer as it is less likely to be misused (Reference Griffith, Carranza and GriffithGriffith 1983) and several studies have demonstrated efficacy of bupropion in the treatment of ADHD with comorbid substance misuse (Table 1). In a 5-week open trial, bupropion was shown to reduce attention and hyperactivity scores among 13 adolescents with conduct disorder in a residential programme for patients who misuse substances (Reference Riggs, Leon and MikulichRiggs 1998). Three other open clinical trials have shown moderate reduction in ADHD symptoms and substance misuse (Reference Solhkhah, Wilens and PrinceSolhkhah 2001; Reference Levin, Evans and McDowellLevin 2002; Reference Prince, Wilens and WaxmonskyPrince 2002). In a 12-week single-blind trial of bupropion (Reference Levin, Evans and McDowellLevin 2002), patients reported significant reductions in attention difficulties, hyperactivity and impulsivity. Self-reported cocaine use, cocaine craving and cocaine-positive toxicologies also decreased significantly. This study concluded that bupropion may be as effective as methylphenidate when combined with relapse prevention therapy, for cocaine misusers with adult ADHD. Conversely, in a 12-week placebo-controlled trial (Reference Levin, Evans and BrooksLevin 2006), sustained-release bupropion did not provide a clear advantage over placebo in reducing ADHD symptoms or additional cocaine use in patients on methadone maintenance treatment. Results from an open trial (Reference Wilens, Prince and WaxmonskyWilens 2010) suggest that in adults with ADHD and substance use disorder, treatment with sustained-release bupropion is associated with clinically significant improvements in ADHD, but not in substance use disorder.

Psychological intervention studies

Good evidence of the effects of psychotherapy in adults is sparse (Reference Nutt, Fone and AshersonNutt 2007), but research supports the use of cognitive–behavioural methods for treating adult ADHD (Reference Young and BramhamYoung 2007; Reference Knouse and SafrenKnouse 2010; Reference Solanto, Marks and WassersteinSolanto 2010). Whatever evidence exists, it is difficult to extrapolate this evidence to the substance use disorder population, as most of these published studies evaluating efficacy of psychotherapy in ADHD exclude patients with substance use disorder.

Literature indicates efficacy for both individual and group CBT in substance use disorder (Reference Liddle, Dakof and TurnerLiddle 2008). Structured, adapted psychotherapies that incorporate motivational enhancement, CBT and/or contingency management to combat substance use disorder can be very useful in treating patients with ADHD and comorbid substance use disorder. In the UK, the Young–Bramham Programme is an integrated programme for understanding ADHD, adjusting to the diagnosis and developing skills to cope with symptoms and associated impairments, including substance use disorder. The programme offers techniques based on psychoeducation, motivational interviewing, cognitive remediation and CBT (Reference Young and BramhamYoung 2007).

Diagnostic assessment

It is important to recognise the challenges inherent in assessing ADHD in the context of comorbidity (Box 4). A study exploring patterns of communication between physicians and patients with ADHD and depression concluded that psychiatrists treating adult patients with depression may not recognise ADHD (Reference Dodson, Findling and EaganDodson 2010). Given the overlap between symptoms associated with multiple psychiatric conditions, it is important to ensure that potential comorbidities are recognised, discussed and addressed.

BOX 4 Assessment of ADHD and substance use disorder

-

• Patients presenting with substance use disorder should be screened for presence of ADHD

-

• Screening instruments for adult ADHD can be invaluable tools in the assessment of this group

-

• Assessment of these individuals should include current and childhood history of ADHD symptoms, detailed history of current and past substance use, previous treatments, and psychiatric, family and forensic history

-

• At least 1 month of abstinence is useful for accurate and reliable assessment for ADHD symptoms

-

• It is imperative to watch for signs of possible misuse, such as missed appointments, and signs of possible diversion, such as repeated requests for higher doses and a pattern of ‘lost’ prescriptions

-

• It is important to exclude high-risk situations (e.g. comorbid antisocial personality disorder, strong forensic history and family member or peers with substance use disorder)

Patients presenting for treatment of substance use disorder should be screened for the presence of ADHD symptoms. Screening instruments for adult ADHD (Reference Barkley and MurphyBarkley 1998; Reference ConnersConners 1998; Reference Kessler, Adler and AmesKessler 2005; Box 5) can be invaluable tools in the assessment of this group (Reference Rosler, Retz and ThomeRosler 2006). It is important to bear in mind that abstinence from drug use may be required to evaluate ADHD symptoms properly. At least 1 month of abstinence is useful in accurately and reliably assessing for ADHD symptoms (Reference BrownBrown 2009).

BOX 5 Screening instruments for adult ADHD

-

• Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale (Reference Barkley and MurphyBarkley 1998)

-

• Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scale (Reference ConnersConners 1998)

-

• Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) (Reference Kessler, Adler and AmesKessler 2005)

A careful evaluation and assessment of these individuals should include history of attention deficit, impulsivity or hyperactivity symptoms in childhood, current ADHD symptoms, substance use, treatments, psychiatric disorders, and a family and forensic history. A comprehensive psychosocial assessment will help to understand particular strengths and difficulties of the individual in various domains.

Treatment considerations

Exacerbation of current substance use disorder, future risk of substance misuse and diversion of psychostimulants complicate treatment of ADHD comorbid with substance use disorder. Evidence so far does not suggest that treating ADHD pharmacologically with stimulants during active substance use disorder exacerbates the disorder. Reference Grabowski, Shearer and MerrillGrabowski et al (2004b) reviewed the data on use of stimulants as a treatment for cocaine addiction. Methylphenidate and amphetamine were variably effective in reducing cocaine use compared with placebo and did not exacerbate any aspects of cocaine addiction. In a meta-analysis using data from six studies (five prospective longitudinal studies and one retrospective study) Reference Wilens, Faraone and BiedermanWilens et al (2003) reported a 1.9-fold reduction in risk of substance use disorders in individuals with ADHD who had taken stimulant medications compared with similar individuals who had not taken such medications. The authors, however, identified several limitations of their meta-analysis, including the small number of studies available and inherent confounding factors that may vary between studies, such as severity of ADHD and the presence/absence of comorbidities. Several longitudinal studies (Reference Molina, Flory and HinshawMolina 2007; Reference Barkley, Murphy and FischerBarkley 2008; Reference Biederman, Wilens and MickBiederman 2008) found no significant effect of stimulant treatment, age or duration of stimulant treatment on the development of substance misuse.

If a stimulant medication is prescribed, there is an important concern regarding its potential for misuse or diversion in this population. A systematic review (Reference Wilens, Adler and AdamsWilens 2008b) found that 5–9% of school students and 5–35% of college students in the USA had used a non-prescribed stimulant over the previous 12 months. Between 16 and 29% of students with stimulant prescriptions had at some time been asked to give, sell or trade their medications. The reasons individuals reported for misusing stimulants were to enhance performance, self-medicate for ADHD symptoms and for their euphorogenic effects (immediate-release stimulants only).

Newer extended-release stimulants and pro-drug formulations minimise the risk of misuse and diversion of drugs (Reference Spencer, Biederman and CicconeSpencer 2006). Lis-dexamfetamine dimesylate (LDX) is the first long-acting prodrug stimulant (Reference FaraoneFaraone 2008). The structure of LDX (covalently bonded d-amphetamine and l-lysine) prevents mechanical drug tampering such as crushing (Reference FaraoneFaraone 2008). Following oral ingestion, it is hydrolysed into l-lysine and active d-amphetamine, which is responsible for the therapeutic effect (Reference FaraoneFaraone 2008). Preliminary evidence suggests the potential for reduced misuse liability of orally and intravenously administered LDX compared with d-amphetamine (Reference Jasinski and KrishnanJasinski 2009).

Management

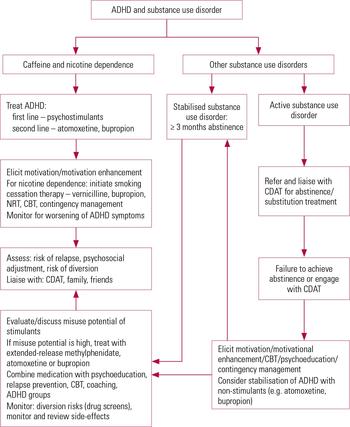

Therapeutic interventions for ADHD and substance use disorder are multimodal with interventions from addiction modalities (drugs and alcohol service, Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous), psychotherapeutic modalities (behavioural and cognitive therapies) and pharmacotherapy. On the basis of our literature review and the current evidence in this area we propose an algorithm to guide clinicians in the treatment of this complex condition (Fig. 1).

FIG 1 Treatment algorithm for the management of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) comorbid with substance use disorder. CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; CDAT, community drugs and alcohol team; NRT, nicotine replacement therapy.

Active substance use disorder should be attended to before the symptoms of ADHD are addressed. Experts often recommend a 3-month period of abstinence before treatment for ADHD may be considered (Reference BrownBrown 2009). However, this may be unrealistic to achieve for patients with significant ADHD symptoms. Some patients with untreated ADHD symptoms may carry the risk of relapse or drop out from the services and find it difficult to engage with other interventions offered. In such cases it is vital to engage patients in an integrated treatment programme and if possible provide an early and aggressive treatment of the ADHD at initial entry into detoxification or rehabilitation programmes (Reference Barkley, Murphy and FischerBarkley 2008).Reference Goossensen, van de Glind and CarpentierGoossensen et al (2006) developed and tested an intervention programme for the screening, diagnosis and treatment of ADHD in patients with substance use disorder in two addiction centres in The Netherlands. Treatment consisted of four interventions (education, medication, coaching and peer support groups) and was simultaneously provided and integrated into the treatment of substance use disorder. The programme was well accepted by patients and feasible to implement. In a naturalistic study, Reference Blix, Dalteg and NilssonBlix and colleagues (2009) evaluated benefits of combined treatment with opioids and central stimulants in a comprehensive treatment facility for substance use disorders. Results were encouraging, with reduction in both opioid misuse and ADHD symptoms and warrant future research to investigate such integrated treatment programmes.

Reference Gray, Himanshu and UpadhyayaGray et al (2009) provide some practical recommendations specifically in relation to smoking cessation in patients with ADHD and nicotine dependence. The authors recommend stabilisation of ADHD symptoms as the first priority of treatment, since untreated ADHD could lead to greater relapse to smoking. The second step is to encourage patients to quit smoking and once that is established the third step is to initiate smoking cessation. A similar approach may be used in treatment of caffeine dependence in patients with ADHD.

Treatment of ADHD with active substance use disorders should entail effective interagency liaison. Close working with agencies involved (e.g. substance misuse, forensic and police services), family and close friends will ensure better monitoring of illicit drug use, treatment adherence and abstinence from illicit drugs.

Close monitoring is vital and it is imperative to watch for signs of possible misuse, such as missed appointments, and signs of possible diversion, such as repeated requests for higher doses and a pattern of ‘lost’ prescriptions (Reference Szobot and BuksteinSzobot 2008). It is important to exclude risk factors for prescription misuse and diversion. These include individuals with comorbid antisocial personality disorder, strong forensic history and family member or peers with substance use disorder.

For those who have stabilised substance use disorder or merely a history of substance use disorder or recreational substance use and no evidence of ongoing diversion or high-risk situations, extended-release or longer-acting stimulants are recommended. For those with active substance use disorder and/or high risk of diversion, non-stimulants such as atomoxetine and bupropion should be considered. Studies (Reference Stoops, Blackburn and HudsonStoops 2008; Reference Sofuoglu, Poling and HillSofuoglu 2009) determining the effects of atomoxetine on administration of stimulants such as dextroamphetamine and cocaine support its safety and tolerability when co-administered with stimulants.

Given the lack of robust evidence for pharmacological interventions in patients with ADHD and substance use disorder, clinicians should make an effort to offer their patients a combination of medication and psychotherapeutic interventions. Psychoeducation for patients and caregivers to inform on the condition, natural history and prognosis is an important element to improve recognition and treatment of ADHD with substance use disorder. Structured, adapted psychotherapies (Reference Young and BramhamYoung 2007) which incorporate motivational enhancement, CBT and/or contingency management to combat substance use disorder can be very useful in treating patients with ADHD and comorbid substance use disorder.

Future directions

Substance use disorder is a highly prevalent comorbidity in patients with ADHD. Although robust evidence exists for pharmacological management of ADHD, there is dearth of evidence for the management of ADHD with comorbid substance use disorder. More research is required to investigate pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments of ADHD with comorbid substance use. It is imperative that mental health professionals receive training in assessment and management of ADHD and substance use disorder. Future guidelines should be more explicit with respect to recommendations for this complex, highly prevalent and impairing condition.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Which of the following statements is false:

-

a studies in both adults and adolescents have found ADHD to be associated with earlier initiation and higher rates of lifetime substance use

-

b substance use can be considered as a form of self-medication for patients with ADHD

-

c abstinence may be more difficult for adults with ADHD

-

d ADHD predicts the development of alcohol use disorders

-

e ADHD greatly elevates risk of substance use and misuse.

-

-

2 Which of the following statements is true:

-

a atomoxetine, a non-stimulant, is a highly specific noradrenergic reuptake inhibitor with high misuse liability

-

b caffeine is an effective treatment for ADHD

-

c studies demonstrate that stimulants are more effective than non-stimulants in treating ADHD comorbid with substance use disorder

-

d bupropion is an effective smoking cessation treatment

-

e nicotine is an effective treatment for ADHD.

-

-

3 Which of the following statements is false:

-

a it is imperative to watch for signs of possible misuse when treating patients with ADHD comorbid with substance use disorder

-

b at least 1 month of abstinence is useful for accurate and reliable assessment for ADHD symptoms

-

c screening instruments for adult ADHD add no benefit in the assessment of ADHD in substance use disorder

-

d patients presenting with substance use disorder should be screened for presence of ADHD

-

e lisdexamfetamine dimesylate has low misuse liability.

-

-

4 Which of the following statements is true:

-

a treating ADHD pharmacologically with stimulants during an active substance use disorder exacerbates the substance use disorder

-

b there is strong evidence that stimulant use in childhood or adolescence increases the risk of developing substance use disorders

-

c newer extended-release stimulants and prodrug formulations minimise the risk of misuse and diversion of drugs

-

d psychological interventions provide no benefit in treating ADHD comorbid with substance use disorder

-

e stimulants have no role in treating ADHD with comorbid substance misuse.

-

-

5 Which of the following statements is false:

-

a therapeutic interventions for ADHD and substance use disorder are multimodal

-

b if substance use disorder is active, it should be addressed prior to attending symptoms of ADHD

-

c for those with active substance use disorder, and/or high risk of diversion, stimulants should be considered as first-line agents

-

d psychoeducation for patients and caregivers is an important element to improve recognition and treatment of ADHD with substance use disorder

-

e substance use in ADHD may be considered as a form of self-medication.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | d | 2 | d | 3 | c | 4 | c | 5 | c |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.