The intense debate surrounding interactions between professional archaeologists and collectors became an actuality for me during my multiyear dissertation research project in southeast Arizona's York-Duncan Valley, an area that represents the far western edge of the Mimbres-Mogollon archaeological culture area. Prior to 2014–2019 investigations, this close-knit rural area was largely an archaeological terra incognita. My research project focused on the reconstruction of precontact settlement patterns in the York-Duncan Valley and the analysis of sociocultural resilience during periods of severe drought in twelfth-century southeast Arizona (Whisenhunt Reference Whisenhunt2020). The project included the identification and recording of sites in an area where residents are often suspicious of outsiders and where archaeology—particularly the remains of larger pueblos—is frequently located on private land. Further complicating research efforts, the handful of known precontact settlements had at best been hand excavated by looters, and at worst, destroyed by mechanical means with few artifacts remaining on the surface. Ultimately, the acquisition of much of the settlement pattern and material culture data required for the project was facilitated by collaboration with former pothunters, who excavated artifacts from burial contexts on private property more than 30 years ago. Even though these excavations occurred prior to the enactment of state laws prohibiting the removal and sale of funerary objects from private land, the collaboration posed ethical challenges. In this article, I discuss research objectives and results, and the navigation of challenging ethical considerations. I also offer a set of best practices that may assist others contemplating similar engagement and that may foster local stewardship and preservation goals.

PROJECT BACKGROUND

The York-Duncan Valley, a 50 km stretch of land along the Gila River, has few extant pueblo archaeological sites remaining from the precontact period. The land modification needed to farm the floodplains and low terraces on the Gila River has taken a significant toll on sites from all chronological periods (Whisenhunt Reference Whisenhunt2020). Rail line and road construction that occurred prior to the enactment of preservation laws demolished major portions of several sites. Surface artifact hunting on private property has long been, and continues to be, a local pastime. However, the most consequential activities associated with the destruction of precontact pueblo settlements over the past 100 years are the legal (before 1990 and on private land with the owner's permission) and illegal excavation of ceramics and other artifacts, known as “pothunting” or “looting.” Even the most pristine pueblo site in the York-Duncan Valley has at least been dug by hand. Others have been nearly or wholly destroyed. At best, a few linear cobble features representing the remains of architecture and a scatter of artifacts remain on the surface. At worst, a settlement or smaller pueblo may be marked only by a handful of pottery sherds and lithics. Even archaeological sites on federal and state land in the York-Duncan Valley often bear the marks of looting, although not the level of mechanical disturbance visible at large sites on private property.

Pothunting in the York-Duncan Valley intensified in the 1980s when the commercial value of precontact painted Mimbres pottery skyrocketed. Locally, excavation was largely focused on sites situated on private property, and it was accomplished with the landowners’ consent. At the time, prior to the enactment of Arizona Revised Statute (ARS) §41-865, the excavation of archaeological sites, including burials, was legal if carried out on private property with the permission of the owner. The 1979 Archaeological Resources Protection Act served as the federal umbrella statute governing removal and sale of archaeological objects. For there to have been a violation of ARPA, an artifact's removal had to have been accompanied by an illegal act. This included excavation or collection from federal, tribal, or state lands or while trespassing on private property. Consequently, under ARPA, the removal of any artifact, including funerary pottery, was legal if it occurred on private property with the owner's permission. In the York-Duncan Valley, hundreds of ceramic vessels and artifacts mostly taken from mortuary contexts were legally sold on the open market or, more rarely, incorporated into small private collections possessed by the site's titular owners. State laws changed in 1990 with the adoption of Arizona Revised Statute (ARS) §41-865, prohibiting private landowners from disturbing human remains or burial goods. The enactment of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in 1990 further bolstered protections to all cultural items found on federal or tribal lands or curated in federal institutions, but like ARPA, it did not apply to artifacts found on private lands or private collections.

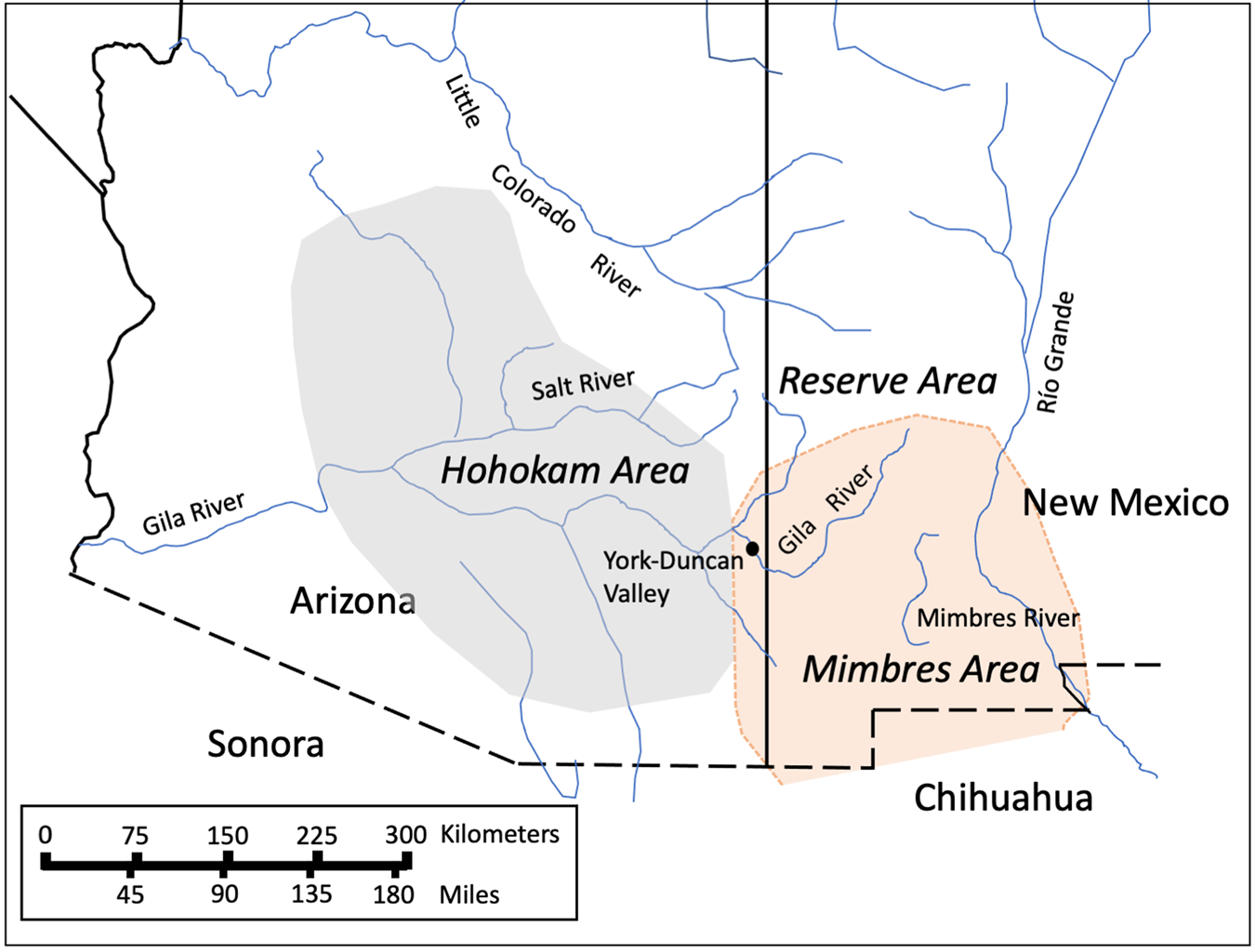

Prior to the start of the project, tribal affiliations to the research area were unclear, given that it lies at the eastern edge of the Hohokam region and the far western edge of the Mimbres-Mogollon region (Figure 1). However, Zuni and Hopi residents of the Western Pueblo villages of New Mexico and Arizona claim cultural affiliation with the people of the Mimbres region (Nelson and Hegmon Reference Nelson, Hegmon, Nelson and Hegmon2010:3). An evaluation of changes in settlement systems in the US Southwest between AD 1200 and 1599 suggests that Postclassic residents in the York-Duncan Valley and others in the region migrated south into Mexico's Sonora region or northeast to Western Pueblo settlements in the fifteenth century, leaving the valley depopulated until the arrival of Apache tribes (Wilcox et al. Reference Wilcox, Gregory, Brett Hill, Gregory and Wilcox2007:173–180). Research results suggest that people living in the York-Duncan Valley during the Classic period (AD 1000–1130/50) were substantially affiliated with residents in the Mimbres core area. One historic (AD 1500–1950) Apache site was also identified during survey.

Figure 1. Regional cultural areas and the York-Duncan Valley study area (created by Mary E. Whisenhunt).

Very little was known about the archaeology of the York-Duncan Valley before 2014. Only a handful of site or cultural resource management (CRM) reports (Berman Reference Berman1978; Lascaux and Montgomery Reference Lascaux and Montgomery2013; Lightfoot Reference Lightfoot1984) were written before the start of the project. Only one—Lascaux and Montgomery's extensive 2013 report on a multicomponent site on the outskirts of Duncan—included the excavation of pueblo structures.

RESEARCH OBJECTIVES AND CHALLENGES

My dissertation project included two fundamental objectives: to broadly reconstruct precontact settlement patterns in the river valley and investigate the nature of sociocultural resilience by evaluating settlement pattern and material culture change between the Mimbres Classic and Early Postclassic periods (AD 1130–1300; Whisenhunt Reference Whisenhunt2020). In the Mimbres-Mogollon region—generally believed to center in the Mimbres Valley (Gilman Reference Gilman, Harry and Herr2018)—this interval was marked by substantial changes in settlement patterns, demography, and material culture representing a social reorganization. Following a period of significant population growth in the Classic period, two severe droughts in the twelfth century are believed to have factored into the depopulation of much of the northern Mimbres River drainage, the dispersal of large villages into hamlets or abandonment of the southern portion of the river valley, and an eastward migration (Grissino-Mayer et al. Reference Grissino-Mayer, Baisan and Swetnam1997; Nelson Reference Nelson1999; Nelson and Hegmon Reference Nelson and Hegmon2001; Roth et al. Reference Roth, Gilman, Anyon, Roth, Gilman and Anyon2018).

Material culture patterns also changed significantly between the Classic and Early Postclassic periods. Classic ceramic assemblages were largely homogeneous, consisting almost exclusively of Mimbres types, with little nonlocal pottery present (Anyon and LeBlanc Reference Anyon and LeBlanc1984; Brody Reference Brody2004; Hegmon et al. Reference Hegmon, Nelson and Roth1998:93). The reorganization of Mimbres society at the end of the Classic period marked the reintroduction of nonlocal ceramics in assemblages throughout the Mimbres region, representing a florescence of new external social relationships (Hegmon and Nelson Reference Hegmon, Nelson, Sullivan and Bayman2007:95). Therefore, the research project involved both determining whether a similar reorganization co-occurred in the York-Duncan Valley and reconstructing a basic occupational history of the precontact periods using survey methods. This involved the identification and recording of archaeological sites and surface artifact analysis on federal, state, and private lands. Architecture and ceramic types found at Classic and Early Postclassic period sites would be the most critical elements in answering research questions associated with the area's sociocultural response to drought.

We expected to find Classic and Early Postclassic sites in the York-Duncan Valley because all other periods in the Mimbres-Mogollon chronological sequence appeared to be represented. During the first two field seasons, however, we found few Classic sites and only one occupation associated with the Early Postclassic period. Initial outreach efforts with the community and personal contacts with a few local landowners resulted in the identification of several sites located on private property, including some with pueblo occupations. However, the poor condition of the sites and the paucity of surface artifacts hindered our ability to answer many research questions. Furthermore, Classic and Early Postclassic sites seemed underrepresented for an area that had a perennial stream and that was adjacent to a substantial amount of arable land.

Near the end of each summer field season, we typically presented an overview of survey and excavation objectives and accomplishments in public forums in Duncan, Arizona. We used these sessions to enhance the public's understanding of the archaeology in the surrounding area and to bolster support for local site preservation and stewardship. We also asked community members if they knew of sites on private property, or individuals with that knowledge. Several names were repeatedly mentioned, including Collaborator 1 and Collaborator 2. Both had been involved in the legal removal of pottery and other artifacts from several local sites in the 1980s. Collaborators 1 and 2 led us to more than 20 unrecorded archaeological sites in the York-Duncan Valley and shared their recollections of the occupations and the associated assemblages. In the process, they introduced us to many ranchers and farmers in the area. These introductions constituted a vital first step in building the trusted relationships necessary to encourage landowners to preserve archaeological sites on their property.

Both informants share a passion for history, particularly the precontact history of the York-Duncan Valley, although neither openly acknowledged their role in destroying it. Unlike Collaborator 1, Collaborator 2 had photographed almost all of the ceramic vessels and other objects removed from the sites, which provided an irreplaceable material record of subsurface archaeology in the York-Duncan Valley. Discussions with both informants continued until the conclusion of project fieldwork in the summer of 2019. Although we continued to survey public and private lands until the project's conclusion, the final two field seasons largely evolved into a labor of reconstruction that involved recording despoiled sites and leveraging data acquired from Collaborators 1 and 2 and other local informants.

EVALUATING PROJECT COLLABORATION PRACTICES

We faced potential ethical and legal issues related to engaging with Collaborators 1 and 2, and integrating data derived from their collections into the research project results. In 2015, the Society for American Archaeology (SAA) commissioned a task force to outline appropriate relationships between professional archaeologists, artifact collectors, and avocational archaeologists (Pitblado et al. Reference Pitblado, Shott, Brosowske, Butler, Cox, Espenshade and Neller2018:14). Following three years of discussions and debate between stakeholder groups, the SAA issued a statement encouraging collaboration between archaeologists and “responsible or responsive stewards” in ways that do not conflict with professional codes of ethics that professional archaeologists have pledged to uphold (Pitblado et al. Reference Pitblado, Shott, Brosowske, Butler, Cox, Espenshade and Neller2018:16). Responsible or responsive stewards include those who collect artifacts legally or who own legacy collections inherited from family members. Stewards also willingly share their knowledge with archaeologists, making their private collections available to researchers and exchanging insights. But as Watkins (Reference Watkins2015:14) argues, there is an inherent tension between the legalities of working with collectors—responsible or not—and the ethics of such collaboration, particularly when data associated with funerary objects are involved. The SAA's Ethical Principal 3 recommends that archaeologists carefully weigh the scholarship benefits of projects involving artifacts not collected by professional archaeologists against the “costs of potentially enhancing the commercial value of archaeological objects. Whenever possible, they should discourage, and should themselves avoid, activities that enhance the commercial value of archaeological objects that are not curated in public institutions” (SAA 1996).

Therefore, when considering whether and how to work with former pothunters—and whether or not to include the analysis of images of unprovenanced artifacts in my research—I had to first ascertain whether the potential informants were responsive or responsible, as described by Pitblado and colleagues (Reference Pitblado, Shott, Brosowske, Butler, Cox, Espenshade and Neller2018:14). At the same time, I had to determine whether the gains of collaboration outweighed the potential losses. Finally, I considered ways to mitigate potential negative consequences of the collaboration and to enhance positive outcomes that included community support for preserving the archaeological record in accordance with published SAA recommendations.

Responsible or Responsive Collectors?

Much of the debate concerning the pros and cons of consulting with collectors has focused on engagement with nonarchaeologists involved in the excavation or surface collection of artifacts on private land, or with individuals who have legally purchased artifacts for their private collections (Cox Reference Cox2015; Deckers Reference Deckers2020; Fisher et al. Reference Fisher, Harris, Schreg and Knipper2015; Pitblado Reference Pitblado2014; Pitblado and Thomas Reference Pitblado and Thomas2020; Shott and Pitblado Reference Shott and Pitblado2015; Thomas and Pitblado Reference Thomas and Pitblado2020; Watkins Reference Watkins2015). Those such as Collaborators 1 and 2, who excavated artifacts from burial contexts on private property before 1990, seem to fall into a ethically grayer area. Excavation was performed legally at the time, but without regard to the ethics involved in removing Native American objects of cultural and religious significance from mortuary contexts. In other words, although it is legal to work with these individuals, is it ethical to do so?

Shott and Pitblado (Reference Shott and Pitblado2015:11–12) argue that collaboration with collectors is warranted only with those who (1) do not loot or buy and sell artifacts for profit, (2) agree to maintain documentary standards (even if they had not before we reached out to them), and (3) make their collections available to researchers for study and recording. They believe that collectors who meet those standards are responsible and that those who might meet them after being educated should be considered responsive. Both Collaborator 1 and Collaborator 2 were careful to point out that they avoided digging on federal and state lands in the 1980s. Based on discussions with both informants, I do not believe that either engaged in the excavation of artifacts after Arizona Revised Statute (ARS) §41-865 was put into force in 1990. Collaborator 2 described how he and his team sped up excavation efforts at a site on Arizona's Blue River as the law's enactment date approached. This suggests that he took the new law seriously enough to curtail his activities when it became enforceable. Several of the photos Collaborator 2 took of artifacts removed from sites also included date stamps, all of which marked the images as taken in the 1980s. Finally, Collaborator 2 became a teacher, whereas Collaborator 1 went on to a career in law enforcement—professions that seem an unlikely (although not impossible) fit for individuals engaged in criminal activity.

In terms of responsiveness, Collaborator 2 photographed nearly all objects taken from all sites he excavated in the 1980s, and in multiple informal interviews, he described the sites and the contexts where the artifacts were found. Collaborator 2 did not maintain a private collection of pottery, suggesting he did not continue to buy or sell personally owned artifacts. Collaborator 1 not only allowed us and visiting scholars to view and record his artifact collection but also facilitated multiple visits to another family member's private collection of pottery. Both individuals led us to many unrecorded sites in the York-Duncan Valley and facilitated introductions to farmers and ranchers where the sites were located. Our interactions with Collaborator 1 and Collaborator 2 suggest that, today, they constitute responsible or responsive stewards of the archaeological record in accordance with Shott and Pitblado's (Reference Shott and Pitblado2015) guidelines.

Collaborators 1 and 2 also served as interlocutors in interactions with many landowners in the local area, creating a path toward building trusted relationships. Continuous long-term engagement with landowners and others in the community allowed us to emphasize the importance of site preservation in developing an accurate settlement history of the York-Duncan Valley. In at least one case, collaboration with a landowner prevented a site from being disturbed. He was unaware that a pueblo ruin even existed on his property and that he had planned to construct a fire pit on or near architectural remains. After we showed him the cobble alignments and ceramic scatters associated with the features, he shelved his plans. In other instances, we were able to offer positive reinforcement of landowners’ ongoing efforts to protect vulnerable sites and artifacts on their private property. We also took the opportunity to discuss the option to preserve privately owned sites by donating them to the Archaeological Conservancy. Although no one took us up on the offer, many are now aware of this option, should they choose to pursue it. Continued nurturing of personal relationships may increase the likelihood that, at some point, landowners or their heirs will choose the Archaeological Conservancy option.

Collaboration and the Commercialization of Artifacts

Another complicating factor in the ethics of collector engagement involves the potential commercialization of artifacts. Publicizing collected or looted artifacts can increase their market value, indirectly legitimize the objects, and encourage future looting (Chase et al. Reference Chase, Chase, Topsey, Vitelli and Colwell-Chanthaphonh2006; Goebel Reference Goebel2015; Lecroere Reference Lecroere2016). Goebel (Reference Goebel2015:29) describes how some collectors invite archaeologists to view and record their private collections, encouraging them to publish their research to bolster the collection's value in the antiquities market. In the York-Duncan Valley, there are at least three small privately owned artifact collections, two of which belong to Collaborator 1 and another member of his family. Most of the items in the collections are artifacts excavated from property owned by the collectors; none were purchased. Although data derived from the collections were integrated into research results, no photos of the artifacts have been published in journals. We have not published any of the photographs taken by Collaborator 2 because the images were originally used in the sale of the artifacts prior to 1990.

Our interactions with all three owners over the past six years suggest that none are interested in selling the artifacts. However, the families do not appear likely to donate their collections to either descendant communities or a research institution. Continued post-project engagement with the families may eventually effect a shift of positions regarding the eventual disposition of the collections.

Some fear that collaborating with those who excavated sites in the past could signify approval of looting on private property or even glorify pothunting on public lands. Some scholars (Goebel Reference Goebel2015; Lecroere Reference Lecroere2016) argue that such collaboration can cause far more damage than provide benefits. Others (Deckers Reference Deckers2020; Pitblado Reference Pitblado2014; Pitblado and Thomas Reference Pitblado and Thomas2020; Thomas and Pitblado Reference Thomas and Pitblado2020) argue on behalf of collaboration, noting that an interactive, nonjudgmental dialogue between archaeologists and responsible or responsive collectors can reinforce the importance of context, provenience, and preservation. A positive relationship can eventually lead to more ethical collection and stewardship processes and, ideally, even the cessation of collecting. Such efforts contribute to SAA stewardship principles and promote public support for preservation goals.

Tribal Involvement

Because the project focused on identifying unrecorded archaeological sites through survey, with tribal affiliations unclear, we did not collaborate with Indigenous representatives. By not doing so, we lost an opportunity to engage with the most important individuals in the collaboration process—those who claim descent from the people we study. Opening a dialogue with tribal representatives as the project progressed would have offered several advantages, including the normalization of a more inclusive research approach to archaeological survey practice. Indigenous knowledge keepers could have offered insights pertaining to ritual structures or artifacts encountered during survey. Three-way dialogue between individuals with private collections, Indigenous knowledge keepers, and us also could have created opportunities to discuss donating collections to descendant communities.

Research Results: Collaboration Benefits

Shott and Pitblado (Reference Shott and Pitblado2015:11) remind us that if we do not use the knowledge provided by collectors, we may condemn damaged or destroyed sites to oblivion. That maxim held true in our interactions with Collaborators 1 and 2. In 2017, Collaborator 1 took our survey team to 11 mostly unrecorded archaeological sites both in the research area and west of the Arizona-New Mexico border. Collaborator 1 also enjoyed extensive personal and familial ties with households throughout the York-Duncan Valley, which opened doors for us that would otherwise have remained shut. Property owners in this rural area tend to be somewhat suspicious of outsiders, so personal reassurances paid enormous dividends in our research efforts over the years as we expanded our informant network. Introductions to other farmers, ranchers, and homeowners with potential sites on their properties and the fostering of those nascent relationships represent an enduring outcome of the collaboration.

These relationships also contributed to a better understanding of local precontact settlement patterns. For example, Collaborator 1 acquainted us with members of a large family represented by multiple households and farms throughout the valley. In one case, an introduction to a family member with a Late Postclassic artifact scatter on his property led to an interview with the owner's uncle, a gentleman in his 90s who lived on the farm in his youth. He described playing around the then-extant walls of a small precontact pueblo on a low terrace overlooking the Gila River floodplain in the 1930s. He was able to recall the general dimensions of the structure and the size of a substantial architectural mound encompassing it. The pueblo was destroyed years later during the construction of a nearby canal. Today, nothing remains of the site except a diffuse scatter of ceramic sherds. The elderly informant passed away in April 2021.

Collaborator 2 met with us on multiple occasions in 2018 and 2019 to discuss sites he was familiar with in the York-Duncan Valley and in the Reserve area north of York. In many cases, he recalled details about artifact and feature spatial contexts. Altogether, he described 11 previously unknown precontact and historic sites in the York-Duncan Valley, accompanying us to visit or record most of them and providing additional details during and after site visits (Whisenhunt et al. Reference Whisenhunt, Hard, Roney and Ludeman2018). He also corroborated several of the site locations and feature and artifact assemblage descriptions provided earlier by Collaborator 1. His descriptions were often supplemented with and verified by photos taken of artifacts and pottery associated with the sites.

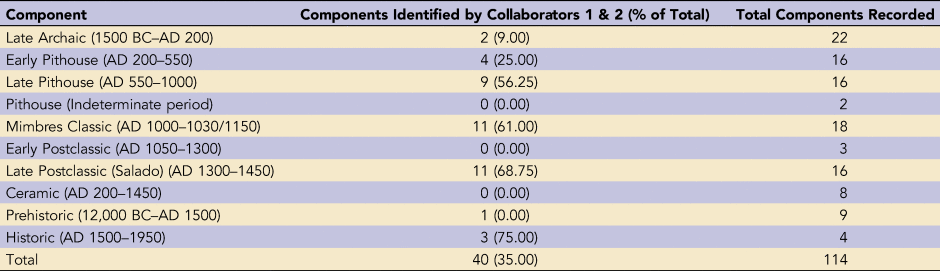

At least 25 of 87 (28.7%) precontact and historic sites formally recorded in this project were identified with the assistance of Collaborator 1, Collaborator 2, and those introduced to us by the two informants. The 25 sites included 40 occupations from various chronological periods, representing more than 35% of the 114 components recorded during this project (Table 1; Whisenhunt Reference Whisenhunt2020). In other words, more than half of all Late Pithouse (AD 550–1000), Mimbres Classic, and Late Postclassic occupations—almost all located on private land—would likely not have been identified and recorded without a collaborative effort that included former pothunters. Both Collaborators 1 and 2 were also able to recall the number of pueblo rooms or pithouses associated with most sites, enabling the estimation of diachronic changes in population from Late Archaic (1500 BC–AD 200) to Late Postclassic periods. Although memories can be unreliable after some 30 years, the dimensions of visible pueblo architectural mounds were consistent with room count estimates provided by Collectors 1 and 2.

Table 1. Number and Percentage of Components Identified with the Assistance of Collaborators 1 and 2.

Images of whole ceramic vessels from Collector 2's photograph collection were critical in our assessment of the diachronic distribution of nonlocal ceramics in York-Duncan Valley sites. Although we had found a handful of Mimbres Style III and Mimbres Corrugated pottery sherds during the survey of several Classic sites, the photographs offered a far more comprehensive picture of subsurface assemblages. In several cases, assemblages associated with the Mimbres Classic period included not only Mimbres ware but also a small number of Hohokam pots attributed to the eleventh century.

Although a few Reserve and White Mountain Red Ware sherds diagnostic of the Early Postclassic period were found during survey, the small assemblages appeared to reflect an incomplete picture of nonlocal wares. The expected fluorescence of nonlocal pottery produced in the Early Postclassic period was evident in photograph images. Unlike the Mimbres Valley, ceramic types found in Early Postclassic contexts in the York-Duncan Valley suggested that external social relationships were almost exclusively focused to the north rather than to the south or east. Overall, settlement patterns and material culture change suggest that the York-Duncan Valley experienced a reorganization similar to that of the Mimbres Valley following two multiyear droughts in the twelfth century. However, its small Classic period population was unlikely to have been a forcing factor in that transformation. Additional details on research results and implications may be found in Whisenhunt (Reference Whisenhunt2020).

Without data from the photograph collection, local recollections of many lost sites, and access to previously unreported sites on private property, our understanding of the occupational history of the York-Duncan Valley would have been fundamentally flawed. I would have significantly underestimated the number and size of both pithouse and pueblo settlements in the valley. Furthermore, without access to images of ceramic vessels in Collaborator 2's photo collection, we would not have been able to recognize the nature or scale of social interactions between precontact residents in the York-Duncan Valley and those within and outside the Mimbres-Mogollon sphere of interaction.

More than 30 years have passed since the informants excavated sites in the York-Duncan Valley. Although the passage of time does not affect the ethical implications of looting, many with whom we collaborated—whether a former pothunter or a farmer who recalled playing among long-vanished pueblo ruins—are elderly. Once these individuals are gone, their memories of sites, features, and assemblages disappear with them.

BEST PRACTICES

To assist other archaeologists who are considering collaboration with those formerly involved in removing artifacts from private lands, I have distilled a short set of recommendations that may help them navigate potential legal and ethical issues and, at the same time, foster preservation of the local archaeological record. However, as Watkins (Reference Watkins2015:15) explains, there is no single “right” answer, and such engagement is highly situational.

(1) Before beginning a research project that involves community engagement of any kind, be fully cognizant of local, state, and federal statutes covering the removal of artifacts—particularly from burials—from sites on private property. Know when the laws were enacted, because this will determine whether an individual removed artifacts legally and whether that collector can be considered a responsible steward. You will also need this information when engaging with landowners who have archaeological sites on their property, particularly if you suspect burials may be present. Be prepared to discuss what federal and state laws do and do not allow, and the reporting process required if landowners find human remains on their property.

(2) To assess whether individuals are responsible or responsive collectors, be prepared to spend a considerable amount of time with them and with other members of the local community. Building trusted relationships with anyone takes time and effort, and few collectors have experienced positive interactions with professional archaeologists. To help you evaluate whether informants collected or sold artifacts legally and shut down excavations involving the removal of funerary artifacts on private land after laws changed, it is simplest to ask. In the case of those who were professional artifact hunters, ask what they did professionally after the new antiquity statutes were enacted and how their lives changed. What was their rationale in removing artifacts? Did their perspective change over the years? It may also be useful to ask local law enforcement officials or trusted community members if pothunters remain active in the local area.

(3) Treat collector informants or collaborators with respect and with appreciation for the time and assistance they provide. Extend that spirit of positive engagement to other members of the community as well because some may have had negative experiences with archaeologists in the past.

(4) Although we regret that we did not do so, reaching out to representatives of possible descendant communities near the local area would establish and nurture a more ethical, holistic approach to your project's collaborative process. Ideally, three-way collaboration between professional archaeologists, owners of privately owned collections, and Indigenous representatives could open the door to the eventual donation of artifact collections to tribal museums or cultural centers by the current owners or their heirs. Establishing a relationship with the potential inheritors of legacy collections may also prevent the future loss or sale of the artifacts. Consider incorporating a project funding line that supports the involvement of Indigenous knowledge keepers or participants in field school/project activities.

(5) Encourage owners of legitimate artifact collections (those acquired legally) to donate them to a research institution or repository. If that approach fails, consider both working with the owners to document the collections and encouraging them to continue making the collections available to other researchers. As outlined by Childs (Reference Childs2015:34), data standards should include the artifact type and cultural period, associated state site number and name, collection date, UTM coordinates where collected, in-site provenience, and two or three photographs of each object with a measuring scale. Consider curating the photos and data in a dedicated digital repository open to other researchers, such as the Mimbres Pottery Images Digital Database (MimPiDD), which is part of the Digital Archaeological Record (tDAR; Arizona State University 2013). One of the advantages of tDAR is its multiple layers of confidentiality, which limits public access. Time constraints prevented my documenting the three collections we accessed during the project, but I hope to do so in future. Photos taken by Collector 2 will be uploaded into and curated by tDAR.

(6) Recognize that a research project requiring involvement with collectors and other community members may be a long-term initiative. As Shott and Pitblado (Reference Shott and Pitblado2015:36) note in their set of Collector Collaboration Interest Group recommendations, ethnographic studies of collecting populations would help us gain a better understanding of their motivations, extent, and desire to interact with professional archaeologists. This is an approach that demands time. In our case, we began outreach efforts in 2014 and continued them even after the project concluded in 2019. The success of the data collection effort was largely predicated on the development of a network of residents who spread the word about our research goals and allowed us to survey their ranches and farms. Equally important, long-term engagement enhanced our ability to promote understanding and support for the preservation of the archaeological record. If we had had only one or two years in which to engage and gather data, we would have failed because there simply would not have been enough time to develop trusted relationships. It made more sense, therefore, to treat the project as a longitudinal research initiative spread out over years. I hope to maintain our post-project presence in the valley by continuing to survey along the Gila River in New Mexico and fostering stewardship principles on the local level. I am also involved with a local effort to develop a nonprofit educational enterprise called the Gila River Academy, a program designed to enhance public knowledge of Gila River Valley ecology and history. As part of this initiative, I hope to create and teach a short course focused on the archaeology of Arizona's Gila River Valley and local site preservation.

(7) When engaging with the local community, find ways to talk about the importance of preserving local archaeology. We discussed the value of context in archaeological investigations, and the way the unscientific removal of surface and subsurface artifacts can distort or eradicate our understanding of precontact occupations. A third message thread that might resonate locally would accurately frame the removal of funerary pottery from burials as grave robbing. In at least two instances in the 1980s, ranchers refused to allow the excavation of burials on their property because of their respect for the dead.

(8) In community engagement, describe what you plan to do with your research results. Provide periodic research updates through presentations or informal discussions. After your project is complete, present your conclusions in local forums. I recently hosted an online presentation to share research findings with Duncan residents.

CONCLUSIONS

Over the past few years, I have found that conducting archaeological settlement pattern research in rural southeast Arizona demands a process that considers interaction with those who excavated artifacts prior to the enactment of ARS §41-865. Outright rejection of a group of people knowledgeable of precontact settlements long removed from the local landscape effectively silences the sites in perpetuity and eliminates opportunities to build the relationships necessary to foster site preservation and achieve stewardship goals. However, ethical engagement with collectors also demands local research and discussions that will help determine whether the individuals are responsible or responsive. A long-term engagement strategy that incorporates that assessment, nurtures community involvement in preserving local archaeology, and creates opportunities for tripartite engagement among collectors, professional archaeologists, and descendant communities offers a potential way ahead in creating an ethical safe space for collector collaboration.

Acknowledgments

This research would not have been possible without the help of community members, particularly local informants, from Duncan, Arizona. I am enormously grateful for their generous support and friendship. My advisor Robert J. Hard and John R. Roney of Colinas Cultural Resource Consulting provided much-needed guidance and assistance. Fellow graduate students and undergraduate students who participated in field schools offered untiring help through several field seasons. I am also grateful to Bonnie Pitblado and others involved in the editorial and review process of this article for their insights and recommendations. Funding for this project was provided through the University of Texas at San Antonio's Graduate School Distinguished Research Fellowship and the Department of Anthropology. Work on Bureau of Land Management property for the duration of the project was accomplished under Permit No. AZ-000591. Access to Arizona state lands in 2015 was authorized under ASM permit 2015-001bl and Temporary Right of Entry (granted May 11, 2015), and under ASM permit 2018-087bl and Temporary Right of Entry 2018-3198 in 2018. All survey was accomplished in compliance with permit terms.

Data Availability Statement

Data in this manuscript are derived from my dissertation (Whisenhunt Reference Whisenhunt2020), available through ProQuest. Additional datasets based on images in the photograph collection, as well as electronic copies of the photos, are available from the author upon request.