Bioarchaeology is the osteological study of archaeological human remains using an anthropological approach (Roberts Reference Roberts2010:38). This field is therefore closely allied to archaeology, which provides the crucial context for interpretation of bioarchaeological data. Bioarchaeology and archaeology share similar research questions and theoretical perspectives but use differing methods to explore the past. As field- and laboratory-based disciplines, archaeology and bioarchaeology use laboratories, field schools, and excursions alongside traditional in-person lectures to equip the next generation of practitioners with the skills needed for their careers (Spiros et al. Reference Spiros, Plemons and Biggs2022). These practical skills are sought after by employers and in some cases are required for the certification of both individual practitioners and degree programs (Colley Reference Colley2004; Passalacqua and Pilloud Reference Passalacqua and Pilloud2020).

Lockdowns and travel restrictions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic have required educators from numerous fields, including bioarchaeology, to offer crucial field training via online delivery (Douglass Reference Douglass2020; Douglass and Herr Reference Douglass and Herr2020; Hoggarth et al. Reference Hoggarth, Batty, Bondura, Creamer, Ebert, Green-Mink and Kieffe2021; Pacifico and Robertson Reference Pacifico and Robertson2021; Scerri et al. Reference Scerri, Kühnert, Blinkhorn, Groucutt, Roberts, Nicoll and Zerboni2020). Although the educational impacts of this transition have been explored in anatomy (Bauler et al. Reference Bauler, Lesciotto and Lackey-Cornelison2022; Papa et al. Reference Papa, Varotto, Galli, Vaccarezza and Galassi2022) and forensic anthropology (Moran Reference Moran2022; Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Collings, Earwaker, Horsman, Nakhaeizadeh and Parekh2020; Villavicencio-Queijeiro et al. Reference Villavicencio-Queijeiro, Pedraza-Lara, Quinto-Sánchez, Castillo-Alanís, Sosa-Reyes, Gómez-Valdes, Ojeda, De Jesús-Bonilla, Enríquez-Farías and Suzuri-Hernández2022), there has been little investigation on the impacts of online education within bioarchaeology. This reflects a broader deficit in educational research in this field, with existing studies being few, outdated, and limited in scope (e.g., Lacombe et al. Reference Lacombe, Quam, Lipo and DiGangi2019; although see Spiros et al. [Reference Spiros, Plemons and Biggs2022] for an exception). Inadequate training has been implicated as a cause of sensationalized and unethically misrepresented bioarchaeological data (Snoddy et al. Reference Snoddy, Beaumont, Buckley, Colombo, Halcrow, Kinaston and Vlok2020). Therefore, there is a clear ethical need for bioarchaeologists worldwide to engage in the development of an updated, relevant, and authentic framework for bioarchaeology education. To develop this framework, it is first necessary to identify the current educational approaches used in this discipline, such as online learning, and to assess whether they are effective for bioarchaeology teaching and learning.

We address the limited education research in bioarchaeology and contribute to the assessment of current teaching and learning practices in this field by exploring the perceived effectiveness of online education in bioarchaeology. We consider two common perceptions around online learning from the standpoint of bioarchaeology education—that (1) online techniques are inadequate for teaching practical skills and (2) online learning environments lack a sense of community, negatively affecting the experiences of learners. We investigated teaching effectiveness and learner experiences through a participant survey of archaeology and bioarchaeology students and professionals who completed a year-long digital masterclass series. We define a “masterclass” as a teaching and learning session that is led by experts (“masters”) in a particular discipline and integrates both passive content delivery and interactive activities. This series aimed to provide a broad overview of the methods and theory of human skeletal analysis. The survey explored student perceptions of learning during the course, the perceived effectiveness of teaching staff and online learning in general, and whether online learning was conducive to the development of a sense of community among participants.

ONLINE EDUCATION PRE- AND POST-PANDEMIC

Online learning refers to teaching and learning performed using digital devices (Mayer Reference Mayer2018). The conceptualization and adoption of online education were made possible by the development of computer networking and email technologies in the 1970s, with the first completely online course offered in the 1980s (Harasim Reference Harasim2000). The subsequent adoption of online education has been slow because of negative perceptions around this teaching modality and the early failures of online learning to deliver according to expectations (Harasim Reference Harasim2000; Lloyd et al. Reference Lloyd, Byrne and McCoy2012; Palvia et al. Reference Palvia, Aeron, Gupta, Mahapatra, Parida, Rosner and Sindhi2018). These perceptions include the feeling that online education is of poorer quality than in-person teaching, leads to lower student engagement, creates more work for academics, and is solely a “revenue-grabbing” exercise by academic institutions looking to “teach more for less” (Lloyd et al. Reference Lloyd, Byrne and McCoy2012; Pacifico and Robertson Reference Robertson2021; Robertson Reference Robertson2021).

Due to these early, widespread concerns about the quality and effectiveness of online education, a large number of reviews and qualitative surveys have focused on student perceptions of online learning. Most studies advocate for the benefits on online learning among nondisabled, neurotypical students (Chakraborty et al. Reference Chakraborty, Mittal, Gupta, Yadav and Arora2021; Hollister et al. Reference Hollister, Nair, Hill-Lindsay and Chukoskie2022; Kulkarni and Chima Reference Kulkarni and Chima2021; Means and Neisler Reference Means and Neisler2020; Muthuprasad et al. Reference Muthuprasad, Aiswarya, Aditya and Jha2021; Papa et al. Reference Papa, Varotto, Galli, Vaccarezza and Galassi2022). These advantages include greater inclusivity, flexibility, and accessibility of online learning, as well as an increased feeling of community and motivation engendered by collaborative online environments (Harasim Reference Harasim2000:50; Kauffman Reference Kauffman2015; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Liu and Bonk2005; Song et al. Reference Song, Singleton, Hill and Koh2004). E-learning may be of additional benefit to students with physical disabilities because of the wider range of assistive technologies available online; it also has been linked to reduced social anxiety among neurodivergent learners (Goegan et al. Reference Goegan, Le and Daniels2022; Hashey and Stahl Reference Hashey and Stahl2014; Rice and Dykman Reference Rice, Dykman, Kennedy and Ferdig2018; Ro'fah et al. Reference Ro'fah, Hanjarwati and Suprihatiningrum2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the mass adoption of online teaching as a means of continuing with education during lockdowns and mandatory isolation periods. Despite the advantages of online learning, nondisabled neurotypical students and teachers have expressed a preference for in-person training, with online learning seen as a temporary measure for use during the pandemic only (Papa et al. Reference Papa, Varotto, Galli, Vaccarezza and Galassi2022:274; Spiros et al. Reference Spiros, Plemons and Biggs2022). In fields such as anatomy, bioarchaeology, archaeology, and forensic anthropology, where practical training is key to developing competency, this rapid pivot in teaching modality raised concerns around the appropriateness of online learning in hands-on disciplines (Kulkarni and Chima Reference Kulkarni and Chima2021; Papa et al. Reference Papa, Varotto, Galli, Vaccarezza and Galassi2022:274; Passalacqua and Pilloud Reference Passalacqua and Pilloud2020; Scerri et al. Reference Scerri, Kühnert, Blinkhorn, Groucutt, Roberts, Nicoll and Zerboni2020; Spiros et al. Reference Spiros, Plemons and Biggs2022; Villavicencio-Queijeiro et al. Reference Villavicencio-Queijeiro, Pedraza-Lara, Quinto-Sánchez, Castillo-Alanís, Sosa-Reyes, Gómez-Valdes, Ojeda, De Jesús-Bonilla, Enríquez-Farías and Suzuri-Hernández2022).

The shift to online learning also highlighted inequities in access to the technological infrastructure required for successful online learning, as well as issues of increased social isolation and reduced motivation and engagement among students (Chakraborty et al. Reference Chakraborty, Mittal, Gupta, Yadav and Arora2021; Hollister et al. Reference Hollister, Nair, Hill-Lindsay and Chukoskie2022; Kulkarni and Chima Reference Kulkarni and Chima2021; Means and Neisler Reference Means and Neisler2020; Miszkiewicz Reference Miszkiewicz2020; Muthuprasad et al. Reference Muthuprasad, Aiswarya, Aditya and Jha2021; Papa et al. Reference Papa, Varotto, Galli, Vaccarezza and Galassi2022). These inequities were particularly severe among students with disabilities, students of color, and students of low socioeconomic status (Goegan et al. Reference Goegan, Le and Daniels2022; Means and Neisler Reference Means and Neisler2021; Mohammed Ali Reference Mohammed Ali2021; Ro'fah et al. Reference Ro'fah, Hanjarwati and Suprihatiningrum2020; Russ and Hamidi, Reference Russ, Hamidi, Vasquez and Drake2021).

Furthermore, a lack of research around the applicability of andragogical theory to e-learning calls into question its overall effectiveness for adult learners in general (Greene and Larsen Reference Greene and Larsen2018). Andragogical theory and online learning share a fundamental emphasis on self-directed learning, flexibility, accessibility, and relevance to learners (Galustyan et al. Reference Galustyan, Borovikova, Polivaeva, Bakhtiyor and Zhirkova2019). As such, “digital pedagogies” and “virtual andragogies” have been proposed to assist educators in leveraging these similarities to increase the efficacy of online teaching (e.g., Anderson, Reference Anderson2020; Greene and Larsen Reference Greene and Larsen2018). These guidelines emphasize flexible course design, the curated use of online tools, and the targeted development of self-motivation skills among learners (Ferriera and Maclean Reference Ferreira and Maclean2018; Greene and Larsen Reference Greene and Larsen2018).

EDUCATION IN BIOARCHAEOLOGY

Because bioarchaeology draws on biological, archaeological, and anthropological theory; requires ethical awareness; and necessitates both theoretical and practical training, bioarchaeology educators experience unique challenges to effective teaching and learning. Similar issues are being addressed in the related fields of forensic anthropology and archaeology through engagement in critical discussion around educational requirements, reflecting on current standards of education, and developing and undertaking benchmarking and accreditation processes (Beck et al. Reference Beck, Roberts, Fairbairn, Ulm, Balme, Frieman, McGowan and Strickland2020; Colley Reference Colley2004; Langley and Tersigni-Tarrant Reference Langley and Tersigni-Tarrant2020; Passalacqua and Pilloud Reference Passalacqua and Pilloud2020; Pinto et al. Reference Pinto, Pierce and Wiersema2020; Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Collings, Earwaker, Horsman, Nakhaeizadeh and Parekh2020).

In contrast, there have been few attempts to critically assess the current standard of bioarchaeology education, including whether it engages with educational best practices, employs modern andragogical principles, or is effective in producing independent practitioners in the field. Most research on bioarchaeology education to date has a practical focus, with works providing broad guidance and resources for people engaged in biological anthropology teaching (e.g., Cohen Reference Cohen, Rice, McCurdy and Lukas2010; Frazetti Reference Frazetti, Rice, McCurdy and Lukas2010; Rector et al. Reference Rector, Day, O'Neill, Vergamini, Volkers, Hernandez and Verrelli2018; Schaefer Reference Schaefer2018; Štrkalj Reference Štrkalj2010).

More recently, there has been discussion of the applicability of bioarchaeology skills to anatomy education (Langley and Butaric Reference Langley and Butaric2020) and the introduction of strategies for supporting blind and low-vision students in laboratory contexts (Blatt Reference Blatt2022). Although there has been extensive critique of the race concept in forensic and biological anthropology in general (e.g., Fuentes Reference Fuentes2021; Go et al. Reference Go, Yukyi and Chu2021; Lasisi Reference Lasisi2021), there remains a lack of specific discourse around race and ancestry in bioarchaeology education although (for exceptions, see Adams and Pilloud Reference Adams and Pilloud2022; Soluri and Agarwal Reference Soluri and Agarwal2022). Recent work by Spiros and colleagues (Reference Spiros, Plemons and Biggs2022) advocates for the development of a digital pedagogy in forensic anthropology and bioarchaeology that accommodates variable levels of technological proficiency, understands different cultural perspectives around learning, and supports accessibility.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The “Living on the Edge” Thai bioarchaeology project was initiated in 2020. This collaborative venture, which included researchers based in Thailand, New Zealand, and Australia, aimed to explore human health during the protohistoric (AD 500–800) social transition in northeast Thailand. In-person bioarchaeology training workshops were to be offered to both students and professionals in archaeology and bioarchaeology alongside the data-collection phase of the project, originally scheduled to take place in Thailand in mid-2021. Data collection was subsequently delayed because of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the original workshops were redeveloped into a year-long online “masterclass” series.

The Masterclass Series

The bioarchaeology masterclass series comprised 10 online seminars delivered monthly between February and December 2021; each 90-minute seminar was offered free of cost over Zoom, which was chosen because it provides a no-cost, easily accessible, and download-free means of communication. Participants were required to provide their own internet connection. They were recruited through open invitations on Twitter and through targeted email invitations to members of existing bioarchaeology and archaeology research networks in Southeast Asia.

Masterclass Participants

Seminar registration data were collected for eight of the 10 masterclasses, which were held between February and October 2021. These data show that registrations per session ranged from eight to 35 individuals, with an average of 17 attendees (SD = 8.14; Supplemental Text 2). All survey participants had a university education, with the largest proportion of individuals currently holding master's degrees (69%, n = 9) and having previous bioarchaeology and archaeology experience (Table 1). Classes were taught in both English and Thai, although all participants self-rated their English language and technological proficiency as average or above (Table 1). Participants were predominantly from Southeast Asia (see Supplemental Text 2 for specific information on participant nationalities).

Table 1. Demographic Information of Participants and Detailed Feedback on Enjoyment of the Masterclass Series.

* Please note that the wording of this question has been altered from the original for ease of understanding. See Supplemental Text 7 for the original survey text.

Masterclass Content

Bioarchaeology incorporates osteological analysis with archaeological interpretation. The masterclass series was therefore designed to provide participants with training in core osteological skills, key archaeological and biological theories used by bioarchaeologists in interpreting osteological data (e.g., the biocultural stress model; Goodman et al. Reference Goodman, Martin, Armelagos, Clark, Cohen and Armelagos1984), and key research practices in bioarchaeology (e.g., hypothesis testing; Supplemental Text 3). The series was structured so that individual sessions built progressively on one another.

The seminars in the first half of the series introduced basic skeletal anatomy, with an emphasis on skeletal landmarks used for age and sex estimation. Age and sex estimations provide crucial information on the population structure of ancient communities, which in turn provides critical context for inferences around life in the past. Methods for age and sex estimation were therefore included in the masterclass series. The series concluded with sessions on specialized approaches used in bioarchaeology, such as the study of paleopathology, stable isotopes, and bone histology. When used to analyze well-contextualized human skeletal remains, these techniques allow for nuanced insights into the biology, society, and environment of past peoples. To situate the skills learned within the wider context of academic research, the seminar series also included sessions covering research design, key research questions investigated in Thai bioarchaeology, and research dissemination. Optional homework was provided for Session 2, “The Research Design,” requiring students to develop a “mini” research proposal (Supplemental Text 4). No other homework was provided throughout the series.

Masterclass Delivery

All project team members were involved in delivering seminars, with contributions ranging from logistical support to developing and presenting classes. All the presenters held PhDs in bioarchaeology or in closely related disciplines such as archaeology, had a minimum of three years of in-person lecturing experience, and had at least six months online teaching experience before the masterclass series began. Teaching approaches included both traditional, “passive” lectures and interactive activities, with instructors aiming to engage in active learning during at least half of each session.

Active learning approaches provide a means of knowledge construction and include “any instructional method that engages students in the learning process . . . [and] requires students to do meaningful learning activities and think about what they are doing” (Prince Reference Prince2004:223). Studies demonstrate that active learning results in greater knowledge retention and higher grades, increased student engagement and lecture attendance, and greater development of expert-like characteristics (Brewe et al. Reference Brewe, Kramer and O'Brien2009; Deslauriers et al. Reference Deslauriers, McCarty, Miller, Callaghan and Kestin2019; Howell Reference Howell2021). Students participating in active learning experiences also report deeper approaches to learning, which are facilitated through clear goal setting (Lizzio and Wilson Reference Lizzio and Wilson2004).

The interactive activities ranged from asking students questions and facilitating group discussions, which encouraged students to actively think about and engage with course content, to online case studies. Case study activities included using standard methods to produce age estimates for detailed images of human skeletal remains and applying sex estimation techniques to digital 3D models provided on the project website. Several interactive online platforms supported these activities: they included an anonymous message board (Padlet, Wallwisher Inc.); a quiz and word cloud generator (Mentimeter, Mentimeter AB [publ]), and a repository of open-access interactive 3D models (Sketchfab, Epic Games Inc.). These platforms provide learners with diverse ways to communicate and visualize concepts and play a significant role in supporting learners of various learning styles and preferences. Although we sought to use reputable 3D models where possible, there remain extensive ethical challenges around using skeletal remains and skeletally derived materials such as 3D models in both online and in-person teaching (Hassett Reference Hassett2018; Ulguim Reference Ulguim2018). We refer readers to Smith and Hirst (Reference Smith, Hirst, Squires, Errickson and Márquez-Grant2019) and Márquez-Grant and Errickson (Reference Márquez-Grant, Errickson, Errickson and Thompson2017) for introductions to this crucial topic.

Participant Survey and Data Analysis

All individuals who registered to attend at least one class (n = 61) were invited to complete a two-part Qualtrics survey via email (Supplemental Text 5 and 6). The survey (Supplemental Text 7) was available online between December 13, 2021, and January 28, 2022. Part 1 of the survey gathered general participant information, such as the highest level of education achieved and the amount and type of experience in bioarchaeology and archaeology. Information on self-rated proficiency in English and self-rated technological skill was collected to allow us to control for the impacts of language and computer skills on feelings of learning and community. Part 2 collected information on participant experiences in the course. Both portions of the survey included Likert-scale type questions and free-text answers.

At the completion of the survey, all data were deidentified. Free-text responses were thematically coded following procedures outlined in Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2022). The occurrence of certain themes and the Likert-scale answers were then tabulated by frequency. All analysis was carried out in Microsoft Excel for Mac version 16.66.1. Inferential statistical analyses were not conducted because of the small number of survey participants.

RESULTS

Assessment of Perceptions of Masterclass Effectiveness

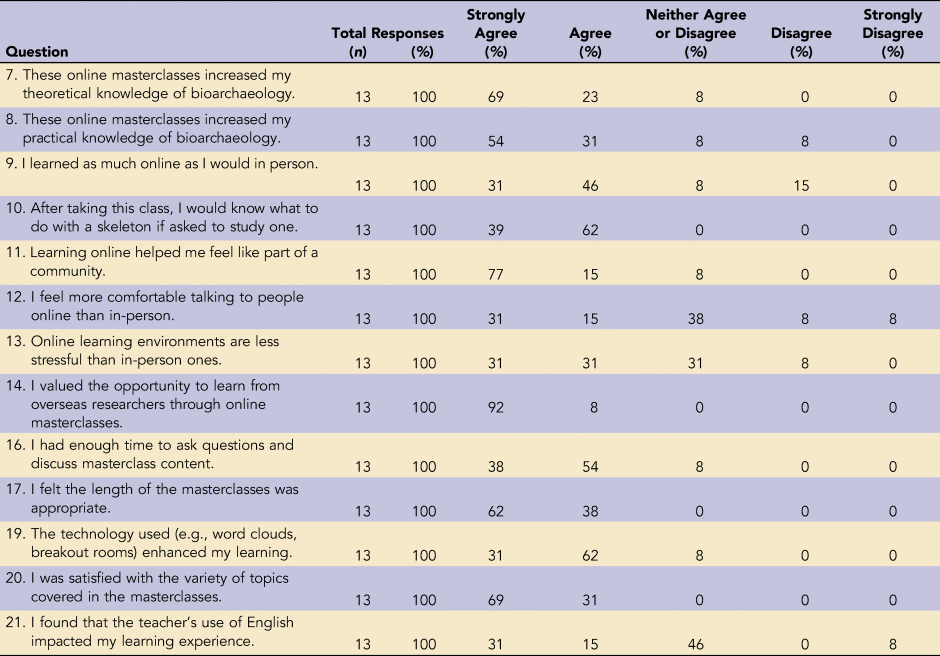

Based on an average of 17 masterclass registrants per class, 76% (n = 13) of participants chose to complete the survey. Most felt that the masterclass series increased their practical and theoretical bioarchaeology knowledge and felt that they learned as much online as they would have in person. All participants expressed the belief that their online training adequately equipped them to work with human skeletal remains should the opportunity arise (Table 2; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Visual summary of responses (n = 13) to survey questions assessed on the Likert scale.

Table 2. Participant Feedback on Masterclass Effectiveness, Sense of Community, and Learning Environment.

Participants expressed a range of feelings around the difficulty of online interactions, with 46% of the class feeling more comfortable communicating through online media than in person, 38% feeling neutral about communicating online, and a further 15% expressing discomfort with communicating online. Most participants did not find online learning any more stressful than in-person environments and identified that learning online helped them feel like part of a community.

All participants valued the opportunity to learn from overseas researchers, although most expressed that they would prefer to do so as part of an accredited university short course offered either online or in person (e.g., a Certificate of Proficiency or Microcredential; Table 1). All participants felt that the opportunity to ask questions, class length, teaching technology employed, and variety of topics covered were adequate (Table 2). Most participants felt that our teaching team's use of English positively affected their learning experience.

All participants expressed enjoyment of the masterclass series (Table 2; Figure 1); they most appreciated the combination of content and teaching style (Table 1). One-third of the participants suggested that being assigned extracurricular activities such as homework would improve the course, and one-quarter requested additional course content. The remaining participants either made no comment or noted that recording the lectures and greater accommodation of personal commitments (e.g., varied class times) would have improved their enjoyment of the course.

DISCUSSION

Bioarchaeology represents a unique blend of practical learning and deep theoretical learning (Biggs et al. Reference Biggs, Tang and Kennedy2023). Practical laboratories, typically those centered on anatomical models and human skeletons, are considered critical for developing the hands-on skills required to become a bioarchaeologist. We therefore aimed to explore the effectiveness of online practical education in bioarchaeology, focusing on two common perceptions around e-learning: that online delivery is inadequate for teaching practical skills and that it does not elicit a sense of community. We acknowledge the small size of our participant pool in the interpretations presented in this section.

Gauging the Perceived Effectiveness of Online Practical Education in Bioarchaeology

Survey participants expressed a sense of confidence around their competence in bioarchaeology following the masterclass series, claiming that online classes increased their practical competency to the point where they felt they would “know what to do” if presented with a human skeleton in a bioarchaeological context. This finding suggests that online masterclasses may be as effective as in-person classes for developing hands-on skills in bioarchaeology. Interestingly, this contradicts research in the fields of anatomy and forensic anthropology, which often characterizes the use of online education as disadvantageous (e.g., Papa et al. Reference Papa, Varotto, Galli, Vaccarezza and Galassi2022; Pather et al. Reference Pather, Blyth, Chapman, Dayal, Flack, Fogg and Green2020; Scerri et al. Reference Scerri, Kühnert, Blinkhorn, Groucutt, Roberts, Nicoll and Zerboni2020; Spiros et al. Reference Spiros, Plemons and Biggs2022). Possible explanations for the positive view of online learning include the teaching approaches employed, the pathways by which adult learners incorporate knowledge, and the perceived relevance of the course content.

All respondents had prior experience in bioarchaeology and archaeology through formal education, practical experience, or a combination of both. This prior knowledge may have helped learners incorporate and interpret new knowledge shared through the masterclass series, resulting in positive perceptions of the effectiveness of online learning (Biggs et al. Reference Biggs, Tang and Kennedy2023; Roschelle Reference Roschelle, Falk and Dierking1995; Saunders Reference Saunders1992). However, incorrect or inaccurate existing knowledge may distort new knowledge. Therefore, teaching and learning can be perceived as effective but still result in the improper application of knowledge and poor student outcomes. It is possible that the feelings of confidence expressed by our participants do not reflect a true understanding of course content. Because students were not asked to demonstrate knowledge or competence in this study, it is not possible to identify or assess the potential impacts of knowledge distortion here.

Adult learners value active, self-directed learning and learning that is both problem centered and relevant to their everyday lives, leading to greater engagement in situations perceived as meeting these requirements (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Lee, Birden and Flowers2003:13; El-Amin Reference El-Amin2020; Knowles et al. Reference Knowles, Holton and Swanson2005; Loeng Reference Loeng2018; Merriam and Bierema Reference Merriam and Bierema2013). There are many strategies for scaffolding learning, including experiential, active, and authentic learning approaches (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Lee, Birden and Flowers2003; Merriam and Bierema Reference Merriam and Bierema2013). These approaches require educators to bring the real-word context into the classroom via problem-based case studies and projects based on authentic scenarios that learners will face (Herrington et al. Reference Herrington, Reeves, Oliver, Spector, Merrill, Elen and Bishop2014; Ornellas et al. Reference Ornellas, Falkner and Stålbrandt2019).

Because all study participants had experience in archaeology and bioarchaeology, and many were currently employed in these fields, it is likely that the masterclass content was broadly relevant to their everyday lives. Throughout the masterclass series we used real-world case studies and drew on our own professional experiences and those of the participants to provide relevant examples of how to apply the course content in the field. Students further gained an authentic and relevant experience by practicing techniques that form the basis of almost all bioarchaeological analysis (e.g., age and sex estimation). We therefore hypothesize that the inclusion of relevant content and the use of active learning approaches increased engagement and engendered feelings of knowledge among our participants.

Exploring Community in Online Education

Survey respondents claimed that the online classes were effective in creating a sense of community and were not more stressful than in-person classes, although some learners also expressed discomfort with communicating in a digital setting. The interpretations offered in this section are based on a small participant pool, and survey eligibility was determined based on the number of classes that participants had completed. This criterion selects for people who had spent more time interacting with each other and our team, so these results may be skewed toward those who felt a sense of community. Alternatively, results may be explained by different cultural preferences around learning and the use of interactive, collaborative teaching approaches and technologies throughout the masterclass series.

A sense of community among learners is key to student engagement, motivation, and performance (Berry Reference Berry2019; Gunawardena and Zittle Reference Gunawardena and Zittle1997; Martin and Bolliger Reference Martin and Bolliger2018; Rovai and Baker Reference Rovai and Baker2005). Several studies have identified mechanisms—collaborative learning approaches, interactive group activities, and use of interactive technologies—through which community can be fostered online (Gunawardena and Zittle Reference Gunawardena and Zittle1997).

Collaborative learning approaches emphasize cooperative group-work and team-based approaches to problem solving, which in turn foster social presence (Johnson and Johnson Reference Johnson, Johnson, Kluge, McGuire and Johnson1999; Qureshi et al. Reference Qureshi, Khaskheli, Qureshi, Raza and Yousufi2021). Shea and colleagues (Reference Shea, Fredericksen, Pickett, Pelz and Swan2001) observed that student satisfaction tends to be higher in collaborative environments, suggesting that the use of collaborative approaches alone may have positively affected perceptions of community and knowledge in our masterclass series.

However, students’ desire to collaborate is shaped by identity, including gender, personality, individual learning styles, and cultural background (Conrad Reference Conrad2002; Ghazal et al. Reference Ghazal, Al-Samarraie and Wright2020). Culture is an especially pertinent factor for the current study, because study participants were drawn from a range of nations, including Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, and Indonesia. Culturally specific approaches are required for effective collaborative learning. For students from Asian Confucian Heritage countries, including Vietnam, Singapore, China, and Taiwan (Nguyen Reference Nguyen2008; Pham Reference Pham2010, Reference Pham2011; Wang and Farmer Reference Wang and Farmer2008; Wang and Torrisi-Steele Reference Wang and Torrisi-Steele2015; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Dennett and Bryan2014), these adaptations include leveraging teacher approval as a motivating factor for students, having instructors focus on “humanitarian” leadership, and focusing on equality among peers. In Thailand, emphasis is placed on viewing teachers as knowledgeable experts, having respect for teachers, ensuring kindness and patience can be found in hierarchical student–teacher relationships, and using teaching approaches that equip students to be independent problem solvers (Suanpang and Petocz Reference Suanpang and Petocz2006; Wong Reference Wong2011). However, additional research is required to gain more nuanced perspectives around the interactions among individuals, cultures, and learning. It must also be noted that existing research investigating relationships between culture and educational engagement is predominantly based on cultural generalizations and fails to recognize the impacts of individual variation in personality, preferences, and behavior.

Breakout room discussions and team activities were used extensively throughout the masterclass series to foster independence and collaboration. Given that both e-learning and collaborative learning are becoming increasingly common in Thai, Vietnamese, and Cambodian educational settings, familiarity with these media may have contributed to a sense of comfort during the series (Heng and Sol Reference Heng and Sol2021; Pham and Tran Reference Pham and Tran2020; Suanpang and Petocz Reference Suanpang and Petocz2006). Furthermore, each breakout room contained at least one team member during each session, allowing us to target educational support to participants in need and build familiarity with them as appropriate. Team members were of varying age, sex, nationality, and seniority to accommodate communication across varying social status levels and to balance conflicting cultural preferences for experts, equality among peers, and hierarchy. Having staff on hand also ensured that we could identify, introduce, and integrate participants who had missed the “meet and greet” session and thereby facilitate their inclusion in the class.

A conscious effort was required by our team to maintain a sense of equality between dominant and “silent” participants. In-class discussions tended to be dominated by those who felt more comfortable in the learning space; this required a dedicated focus on more inactive participants to ensure that they were engaged. However, we recognize that educational engagement may look different for different people and respect that people may also have a wide variety of reasons for not participating. We employed technologies such as Padlet and the Zoom chat to allow participants to engage nonverbally and anonymously if they chose, supporting those with social anxiety or concerns regarding communication.

All participants self-identified as having strong English-language skills, suggesting that language barriers were not responsible for the varied interactions we witnessed; however, Kumi-Yeboah and colleagues (Reference Kumi-Yeboah, Dogbey and Yuan2017) observe that difficulties understanding culture-specific references, challenges identifying nonverbal cues, and the short, “only business” nature of online communications (e.g., short chat messages) may discourage student interactions. Research has also demonstrated that people from Thailand, Cambodia, and the Philippines may recognize large divides in social status and subsequently adopt a self-effacing approach to communication in group settings (den Brok et al. Reference Den Brok, Levy, Wubbels and Rodriguez2003). The variation in engagement may also be related to the cultural concept of face, so that students who are less confident in their knowledge may refrain from speaking out to protect their reputation among their peers (Nguyen Reference Nguyen2008). Gently challenging “silent” recipients and diverting discussions away from dominant personalities may have unintentionally created a mild challenge to face for both parties. Nguyen (Reference Nguyen2008) observes that this gentle challenge may motivate students to work hard to save face, increasing their engagement and, subsequently, their sense of community. However, the negative effects of losing face must be mitigated through actions such as giving credit and compliments where appropriate.

In the current study, both online “meet and greet” and icebreaker activities were used at the beginning of the masterclass series to allow participants to build relationships both with one another and the project team. These activities have been identified as particularly important in multicultural classrooms, because they allow students to acknowledge cultural differences and share knowledge around these (Martin and Bolliger Reference Martin and Bolliger2018; Song et al. Reference Song, Singleton, Hill and Koh2004; Tu and McIsaac Reference Tu and McIsaac2002; Volet and Ang Reference Volet and Ang1998). Relationship building in turn allows trust, group identity, a pleasant atmosphere, and a feeling of safety to form, contributing to a sense of community (Conrad Reference Conrad2002; Nguyen Reference Nguyen2008). Establishing clear norms around behavior has also been shown to support trust formation and collaboration among multidisciplinary teams (Harris and Lyon Reference Harris and Lyon2013). “Rules of engagement” were not, however, established at the beginning of the masterclass series, which is an area for improvement for future offerings.

The “meet and greet” for the current study began with a short presentation introducing the masterclass series and our research team. Photos of the team were provided, and each team member was invited to introduce themselves and their research. This helped establish team members as “experts” and “kind mentors” in the classroom (Nguyen Reference Nguyen2008; Wong Reference Wong2011). However, to moderate this sense of hierarchy, participants were also invited to introduce themselves and to share suggestions for course content and learning outcomes alongside our team. Involving students in decision-making processes situates them as active partners in their own education and increases student engagement and motivation (Adie et al. Reference Adie, Willis and Van der Kleij2018; Healey et al. Reference Healey, Flint and Harrington2016).

The performance of “caring and sharing” behaviors was intended to support the development of community and accommodate generalized cultural preferences for kindness, patience, and familial connections (Nguyen Reference Nguyen2008; Pham Reference Pham2010; Song et al. Reference Song, Singleton, Hill and Koh2004; Tu and McIsaac Reference Tu and McIsaac2002; Wong Reference Wong2011). Instructors engaged in these behaviors by allowing class time for informal, personal discussions, as per Martin and Bolliger (Reference Martin and Bolliger2018). Conversations often revolved around the ongoing pandemic. Although participants had experienced the pandemic in different social, economic, and cultural settings, the many universal experiences of this event, such as lockdowns, mask use, and case numbers, provided “common ground” for our diverse group and enabled all participants to take part in the conversation.

Although most students were amenable to sharing and discussing ideas during the masterclasses, technical difficulties such as unstable internet connections impeded this process for some. These difficulties highlighted inequities in access to technology among our cohort, which were intensified by the additional challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic (Beaunoyer et al. Reference Beaunoyer, Dupéré and Guitton2020; Cheshmehzangi et al. Reference Cheshmehzangi, Zou and Su2022). Flexible learning has been identified as a way of overcoming educational and technological inequities, because it allows students to engage in their studies in the learning style, time, and location of their choice and accommodates individual experiences of illness and disability (Hollister et al. Reference Hollister, Nair, Hill-Lindsay and Chukoskie2022; Means and Neisler Reference Means and Neisler2020; Muthuprasad et al. Reference Muthuprasad, Aiswarya, Aditya and Jha2021; Nkomo and Daniel Reference Nkomo and Daniel2021; Picardo et al. Reference Picardo, Denny, Luxton-Reilly, Szabo and Sheard2021; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Collings, Earwaker, Horsman, Nakhaeizadeh and Parekh2020).

Masterclass participants noted that take-home assignments, extended course content, recordings of lectures, and increased flexibility around the timing of masterclass sessions would further increase their satisfaction with the masterclass series. Kay and Mann (Reference Kay, Mann, Kay and Hunter2022) have advocated for the use of student video assignments and feedback videos to increase the effectiveness of communication between students and instructors and promote a deeper understanding of course content. However, Horn (Reference Horn2020) and Picardo and colleagues (Reference Picardo, Denny, Luxton-Reilly, Szabo and Sheard2021) suggest that the use of recordings may exacerbate existing educational inequities and promote unhelpful student behaviors such as binge watching.

Limitations and Future Direction

We feel that it is important to reflect on our positionality in this research. “Positionality” refers to the biases, assumptions, and worldviews that researchers bring to their interpretations, which are constantly shaped and reshaped by their identity and beliefs (Holmes Reference Holmes2020; Rivera Prince et al. Reference Rivera Prince, Blackwood, Brough, Landázuri, Leclerc, Barnes and Douglass2022). This research was collaboratively developed and conducted by a multicultural team, including early career, mid-career, and senior career females from New Zealand; an early career male and senior career female from Thailand; and a mid-career female from the European Union. The two first authors (SMW and ALB), as white scholars attempting to describe how other cultures may think and feel in education, acknowledge the need to be aware of the colonial overtones surrounding their work. To avoid speaking for other people and cultures, they have actively worked to include the voices of Thai researchers, such as RS and NW, through both collaboration and citation. Our team also actively consulted with our participants regarding masterclass content to ensure they were included as our partners in teaching and learning.

Recruitment strategies for the masterclass series included open invitations on Twitter and targeted email invitations distributed through existing bioarchaeology and archaeology research networks in Southeast Asia. Our ultimate participant pool was relatively small, and future recruitment will target a broader range of platforms. For example, recent research (Ganbold Reference Ganbold2022; Kemp Reference Kemp2021) has highlighted the popularity of YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram across Southeast Asia. An alternative research approach involves investigating online learning and community in existing learner cohorts, such as university courses or professional organizations in the region. These approaches may also be used in tandem to complement recruitment and provide an avenue for comparative studies among varying cohorts. Investigating regional and cultural variations in learning and attainment of educational outcomes in a diverse range of bioarchaeology practitioners worldwide will enable the development of culturally and ethically appropriate curricula.

Although initial interest in the masterclass series was high, attendance was lower and declined throughout the series, suggesting issues with learner retention. Attendance and retention were likely influenced by a range of factors both internal and external to the study, including changing personal and professional commitments, ongoing and variable pandemic challenges, and a declining lack of interest in (or lack of relevance of) course material. Possible solutions to this issue include varying class times and providing recordings and take-home materials to support flexible learning, incentivization of participation (e.g., financial remuneration, awarding official qualifications), increased consultation with participants around course content, and greater use of active teaching techniques.

The survey was designed to capture only qualitative information on general perceptions of the course, such as feelings of enjoyment while learning. As such, few empirical conclusions can be drawn regarding the true effectiveness of the series or the attainment of educational outcomes, including competence in the field of bioarchaeology. Future studies may benefit from including assessments of student competence in their survey instrumentation.

KEY CONSIDERATIONS FOR EDUCATORS

To stimulate discussions around bioarchaeology education and provide a starting point for future research, we provide the following suggestions for improving the effectiveness of online learning. Although framed from the perspective of bioarchaeology, they address broad themes that are common to teaching and learning across many hands-on disciplines such as archaeology. These themes include relationship building, respecting cultural diversity, and supporting learners of diverse backgrounds. These suggestions are therefore broadly applicable to any teachers engaging in multicultural, online, or practical education.

• Actively encourage social interaction and relationship building through virtual icebreakers (both student–student and student–teacher) prior to “formal” classes. It may also be beneficial to have a “students only” gathering to allow learners to engage authentically with one another, although one may choose to appoint a student leader to head lead conversation in this instance.

• Consider setting clear rules of engagement for social interactions in collaboration with your students and research partners. These guidelines may reduce social anxieties around appropriate behavior in cross-cultural settings. Having participants role-play activities demonstrating appropriate behaviors (or if participants are not inclined to participate in this role play, having teachers act out scenes in front of the class) may help clarify what these behaviors look like.

• During the relationship-building process, encourage students to share their reasons for taking the course. This information can be used to tailor course content, encouraging active and inquiry-based learning and greater student retention over time.

• Acknowledge cultural diversity in your classroom (Taylor and Sobel Reference Taylor and Sobel2011), and if appropriate, facilitate discussions between learners about how this may shape their approaches to learning. This discussion can be extended into a guided reflection around the challenges and varying cultural perceptions of working in your field. For example, working with the dead can be a socially, emotionally, culturally, or politically charged experience, and reflections may assist students to develop self-awareness and a greater appreciation of the significance of their work.

• Use active and collaborative teaching approaches where possible to increase student engagement and achievement. Allowing students to lead during these activities may increase feelings of responsibility and engagement with content.

• Consider providing noncompulsory take-home assignments for students, which may help students identify areas for improvement.

• Provide lecture recordings to support flexibility in course attendance and consider the need to create a sense of community for those who do not attend synchronously. Social media, chat rooms, and message boards are commonly used tools for developing social presence among asynchronous learners (Akcaoglu and Lee Reference Akcaoglu and Lee2018; Gunawardena and Zittle Reference Gunawardena and Zittle1997; Tu and McIsaac Reference Tu and McIsaac2002).

• Consider completing training in teaching and learning to better understand the complexities of working with adult learners. A wide array of training options are available to accommodate individual circumstances. These options range from short- and longer-term study programs (e.g., graduate diplomas in adult education, degrees in education), training offered through institutional centers of learning and teaching, courses offered through centers for continuing adult education, and self-directed teaching endorsements (e.g., fellowship of the Higher Education Academy).

CONCLUSION

To stimulate dialogue around bioarchaeology education and facilitate the development of bioarchaeology-specific educational approaches, we explored the effectiveness of online education in bioarchaeology. Through a participant survey, we explored two common perceptions around online learning: that online education is an ineffective means of teaching practical skills and online learning environments lack a sense of community, negatively affecting learner experiences. Our findings suggest that learners perceive online seminars to be an effective means of providing practical training, with participants expressing feelings of practical competence, community, and comfort in the online setting. The use of active and collaborative teaching techniques within a culturally aware educational framework may be a promising alternative for online practical training in bioarchaeology. However, deeper appreciation of the factors influencing student participation and retention and of the varied relationships between student participation and educational success is required for a nuanced understanding of the effectiveness of online practical learning in this field.

Acknowledgments

Ethics approval for this survey was granted by the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee (D21/263, 2021). We thank Bernardo Arriaza for providing the Spanish translation of our abstract.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by a 2021 University of Otago Research Grant awarded to SH.

Data Availability Statement

We are required to protect the anonymity of our survey participants under ethical approvals granted by the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee (D21/263). Original survey data and individual responses are therefore not available to researchers outside our project team. Anonymized, aggregated (e.g., cohort level) survey data are available from the corresponding author by request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.

CRediT Statement

Stacey M. Ward and Anna-Claire L. Barker have both contributed equally to this publication and share first authorship. Stacey M. Ward: Conceptualization (Equal); Data Curation (Lead); Formal Analysis (Lead), Funding Acquisition (Equal); Investigation (Equal), Methodology (Equal); Data Visualization (Lead); Project Administration (Equal); Writing Original Draft (Equal); Writing: Review and Editing (Lead). Anna-Claire L. Barker: Conceptualization (Equal); Investigation (Equal); Formal Analysis (Supporting); Methodology (Equal); Data Visualization (Supporting); Project Administration (Supporting); Writing: Original Draft (Equal); Writing: Review and Editing (Supporting). Rasmi Shoocongdej: Conceptualization (Supporting); Funding Acquisition (Supporting); Investigation (Supporting); Supervision (Supporting); Writing: Review and Editing (Supporting). Naruphol Wangthongchaicharoen: Conceptualization (Supporting); Investigation (Supporting); Writing: Review and Editing (Supporting). Justyna J. Miszkiewicz: Conceptualization (Supporting); Funding Acquisition (Supporting); Investigation (Supporting); Writing: Review and Editing (Supporting). Charlotte L. King: Conceptualization (Supporting); Funding Acquisition (Supporting); Investigation (Supporting); Writing: Review and Editing (Supporting). Siân E. Halcrow: Conceptualization (Equal); Funding Acquisition (Equal); Investigation (Equal); Formal Analysis (Supporting); Methodology (Equal); Data Visualization (Equal); Project Administration (Equal); Supervision (Lead); Writing Original Draft (Equal); Writing: Review and Editing (Supporting).

Supplemental Material

For supplemental material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2023.16.

Supplemental Text 1. Thai-Language Abstract.

Supplemental Text 2. Masterclass Registration Data.

Supplemental Text 3. Biological Anthropology Masterclass 2021 Class Outline.

Supplemental Text 4. Homework from Seminar One.

Supplemental Text 5. Survey Invitation.

Supplemental Text 6. Participant Information Sheet.

Supplemental Text 7. Survey.