The use of social networks for public engagement in archaeology, the possibilities of rapid dissemination of archaeological heritage, and the challenges of ensuring sustainable online participation via social networks are major concerns discussed by different researchers who have investigated social media use in the field of archaeology. In general, the main challenge for any archaeological organization is to determine what to promote—and how—in order to create and maintain a coherent presence on social media (De Man and Oliveira Reference De Man and Oliveira2016). Professional archaeological bodies find themselves increasingly concerned with marketing and the creation of a strong online brand, as well as with the means to deploy social media to establish their research presence and pursue forms of participatory, multivocal dialogue (Pett Reference Pett and Bonacchi2012). The use-value of social media for these institutions can be most obviously understood through the frame of marketing or informing the public about activities, thereby ensuring that the reach of their publicity grows among, between, and around individuals and communities in social media spaces (Kidd Reference Kidd2010).

Facebook consistently proves to be one of the most popular social media platforms, having transformed the social media landscape by providing a unique setting for individual and professional online presences (Matthews and Wallis Reference Matthews and Wallis2015; Pett Reference Pett and Bonacchi2012). The platform is widely used by archaeological organizations to help implement their essential goals and activities, such as branding and marketing, broadcasting and outreach, and participation and community engagement (De Man and Oliveira Reference De Man and Oliveira2016; Goskar Reference Goskar and Bonacchi2012; Whitcher-Kansa and Deblauwe Reference Whitcher-Kansa, Deblauwe, Kansa, Kansa and Watrall2011; Marakos Reference Marakos2014; Matthews and Wallis Reference Matthews and Wallis2015; Pett Reference Pett and Bonacchi2012; Richardson Reference Richardson2014; Walker Reference Walker2014).

Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA), https://www.mola.org.uk, is one of the leading archaeological companies in the UK, providing professional archaeological services and implementing award-winning community engagement programs with a high-profile online presence (Museum of London Archaeology 2019). According to the website, MOLA is involved in both commercial and community archaeology, and the organization has a dual mission serving different goals. As a commercial organization, it seeks to provide professional heritage advice and services to help development-, infrastructure-, and construction-sector clients meet their planning process requirements. As a nonprofit company, it aims to not only inspire people to be curious about their heritage but also share knowledge and information with the widest audiences to strengthen communities and create a sense of place.

MOLA has established several online presences to support its mission and organizational needs. These include a website and blog, as well as different social media sites such as Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, Academia.edu, and a recently opened Instagram account. Its Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/MOLArchaeology, supported by more than 13,000 followers, is a useful addition to the organization's online publicity (Museum of London Archaeology 2018). It may be seen as a successful example of sustainable social network communication, in the context of what Jenny Kidd identifies as the realm of the “marketing frame” in museums/heritage organizations (Kidd Reference Kidd2010). (Note that this “frame” can be contrasted with Kidd's (Reference Kidd2010) conception of the use of social media for inclusivity and collaboration). While MOLA is successful in applying social media to spread the word and attract people to its activities, it is fair to say that it “misses opportunities to explore ways of aligning the marketing frame more honestly (and creatively) with users’ experiences of (and within) the spaces of the technology” (Kidd Reference Kidd2010:68–69).

This review explores different aspects of MOLA's Facebook page seeking to showcase how the organization uses the social network on a day-to-day basis to communicate with its community of followers and how these activities align with users’ experiences and reactions, measurable via Facebook metrics. I rely on quantitative and qualitative data analysis, examining MOLA's Facebook practices by classifying posts by their activity type and by thematic coverage (described below). Moreover, to understand the value of the posted content to the audience, users’ responses are measured in relation to indicated content types, and sentiment analysis is applied to users’ comments.

DEFINING CONTENT ON MOLA'S FACEBOOK PAGE

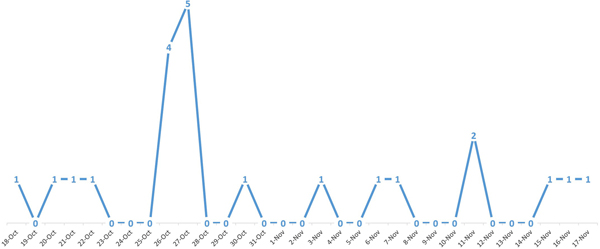

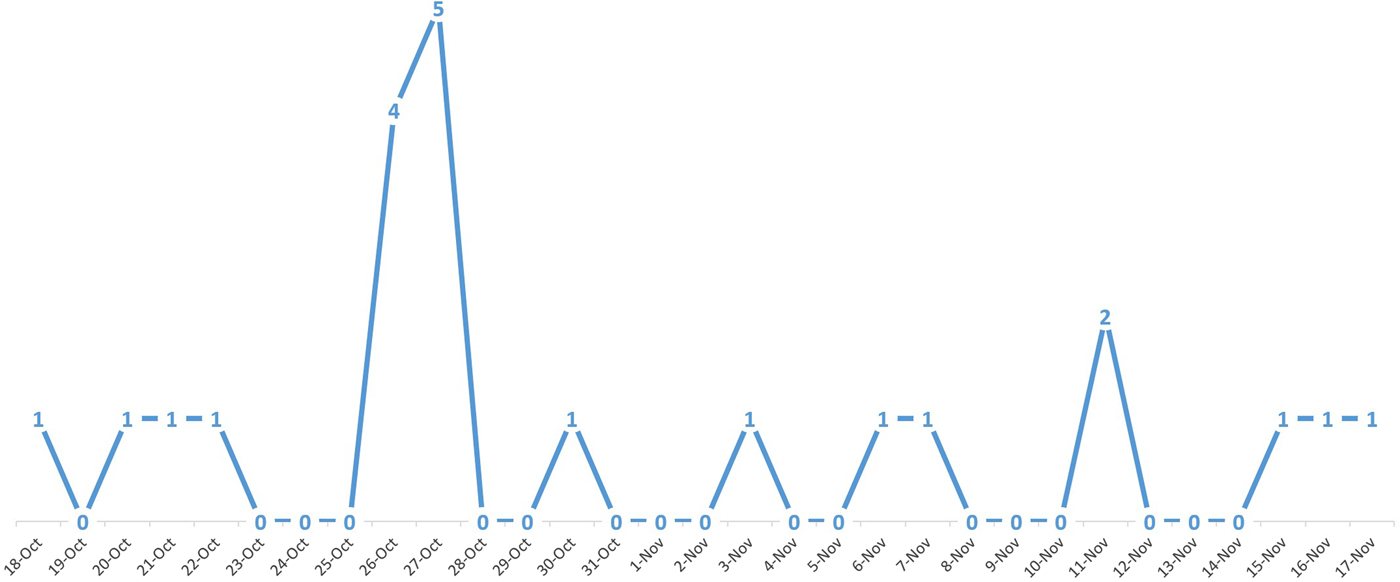

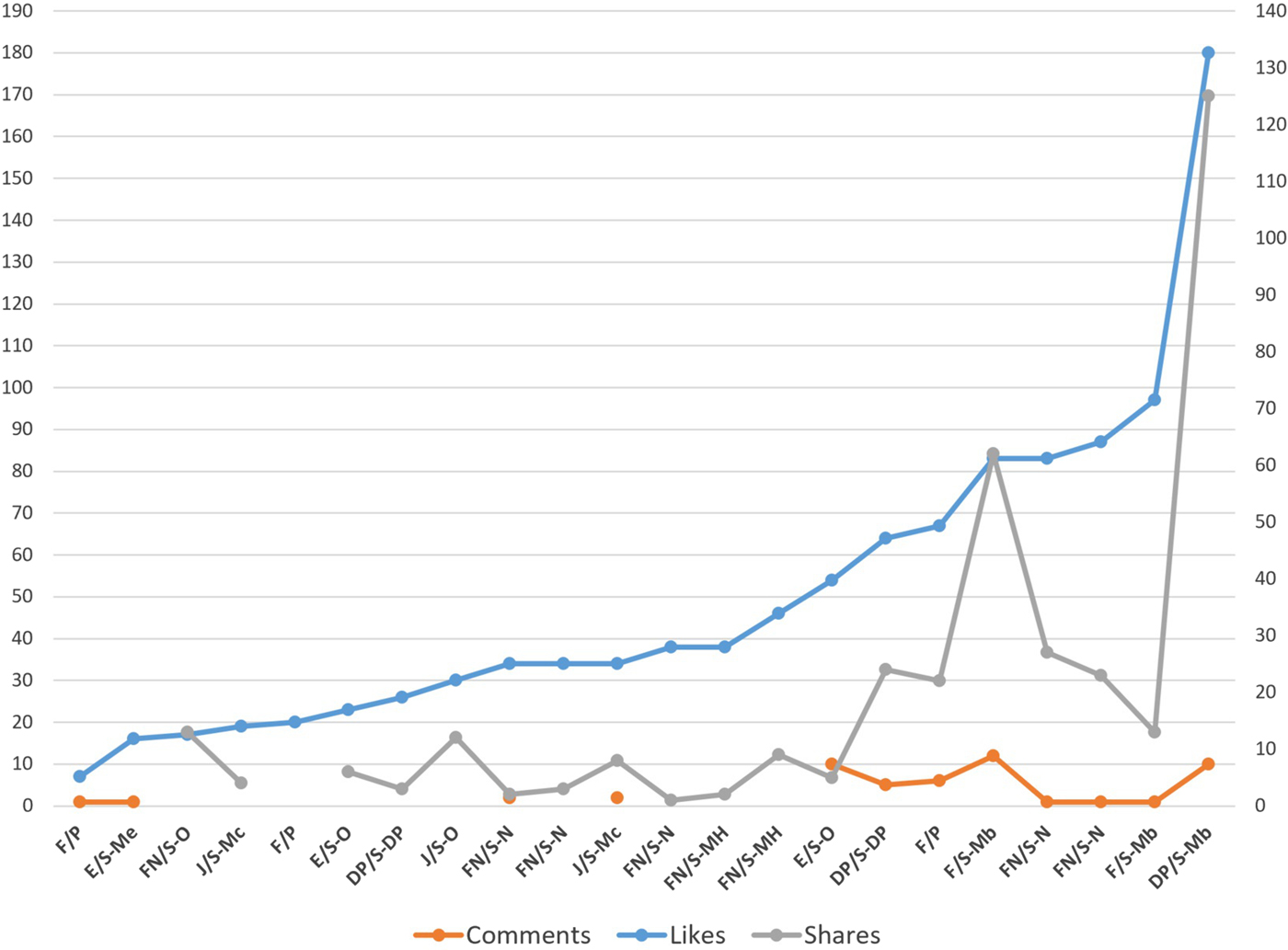

In order to better understand the nature of the content posted on MOLA's Facebook page and to measure its impact on the audience, I observed interactions on the page over a period of one month.Footnote 1 I then performed qualitative and quantitative data analysis on posts and user comments created during that time. This one-month sample was chosen to present a snapshot of day-to-day performance and focused on recent activity (carried out within the last year). My observations suggest that MOLA is an active user of Facebook, sharing 22 posts during the one-month period. Posting is a regular activity for the organization, and it is usually performed every few days (Figure 1). In comparison, similar archaeological organizations share far fewer posts on their Facebook pages. For example, Headland Archaeology (UK) Ltd shared 14 posts during the same period, Archaeology Wales posted just twice, and the Council for British Archaeology just once.

FIGURE 1. Posting frequency on MOLA's FB page, October 18, 2018 to November 17, 2018.

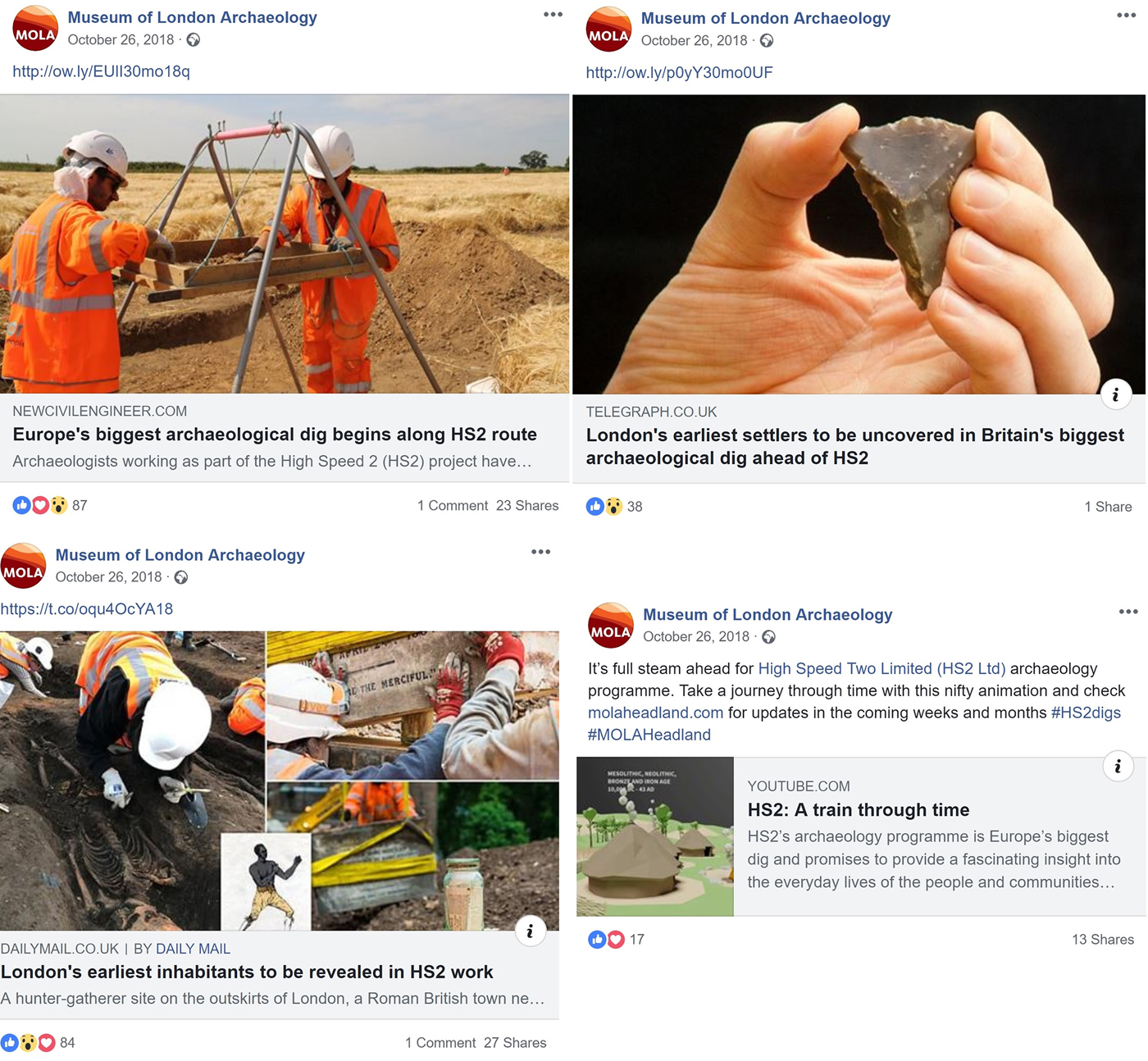

The frequency of posting differs, and an observed peak of posting was linked to the organization featuring news about High-Speed 2, one of the largest excavation projects in history in the UK. During the peak (Figure 1), nine posts were shared, with seven of them directly related to the HS2 excavations and most of them providing links to external news portals, such as the Telegraph, Daily Mail, and The Independent. In other words, Facebook was primarily used by MOLA to consolidate news from different communication channels and to provide relevant information about an ongoing excavation (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. MOLA's posts showcasing the aggregated news from different sources about ongoing HS2 excavations.

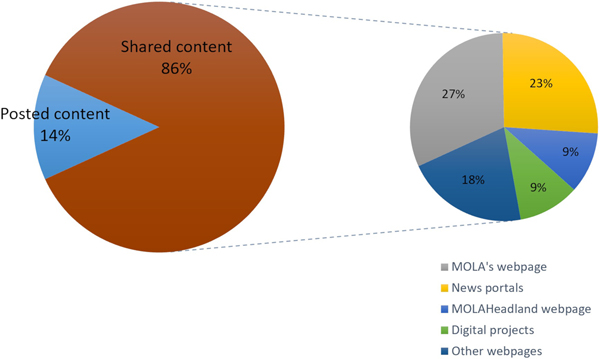

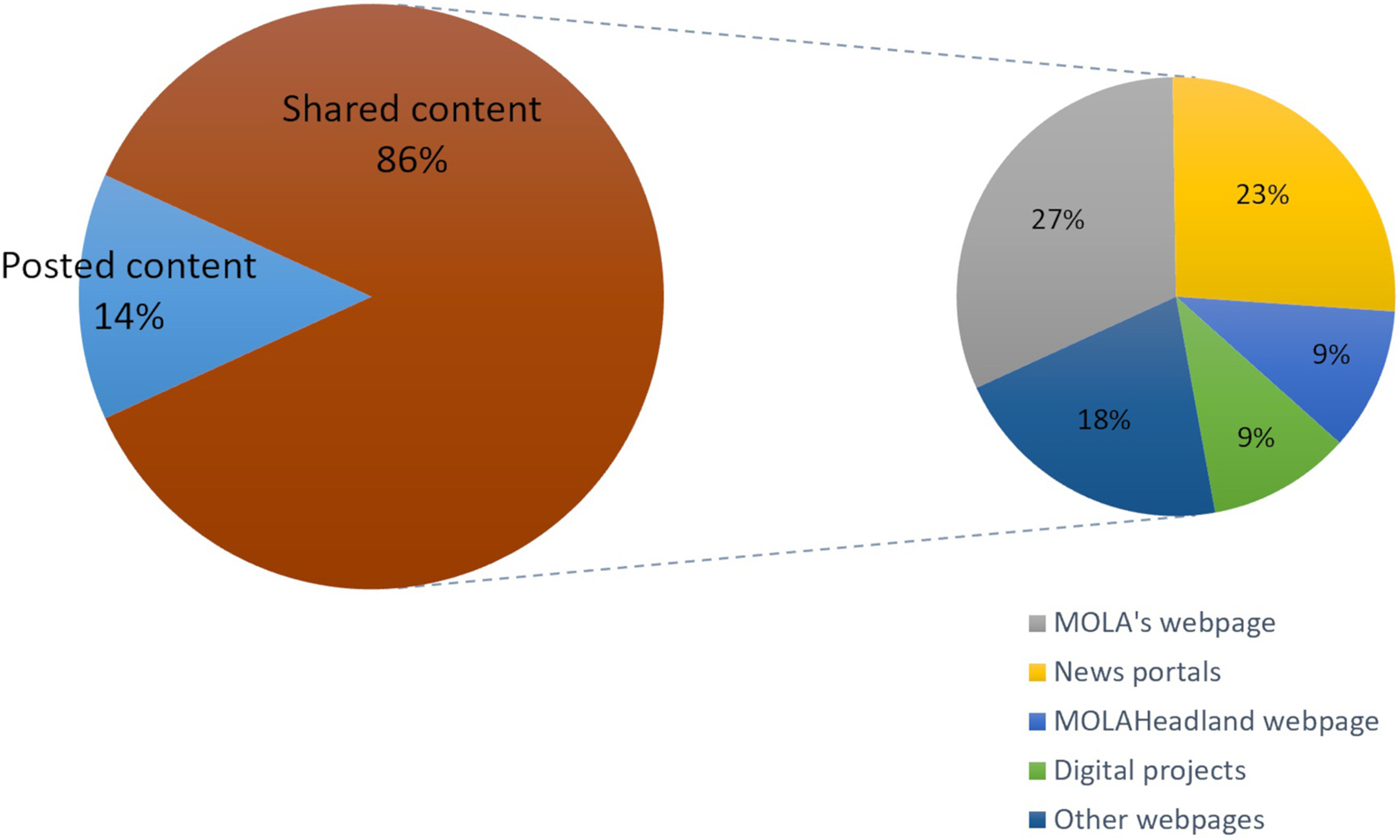

Overall, sharing content and linking it to different webpages appears to be an important activity for MOLA, as the vast majority of content (86%) is composed of shared links rather than original content (Figure 3). These links usually redirect users to primary sources of information, with MOLA's webpage being the most commonly disseminated source on its Facebook page.

FIGURE 3. Proportional representation of posted (original) versus shared content and its primary sources.

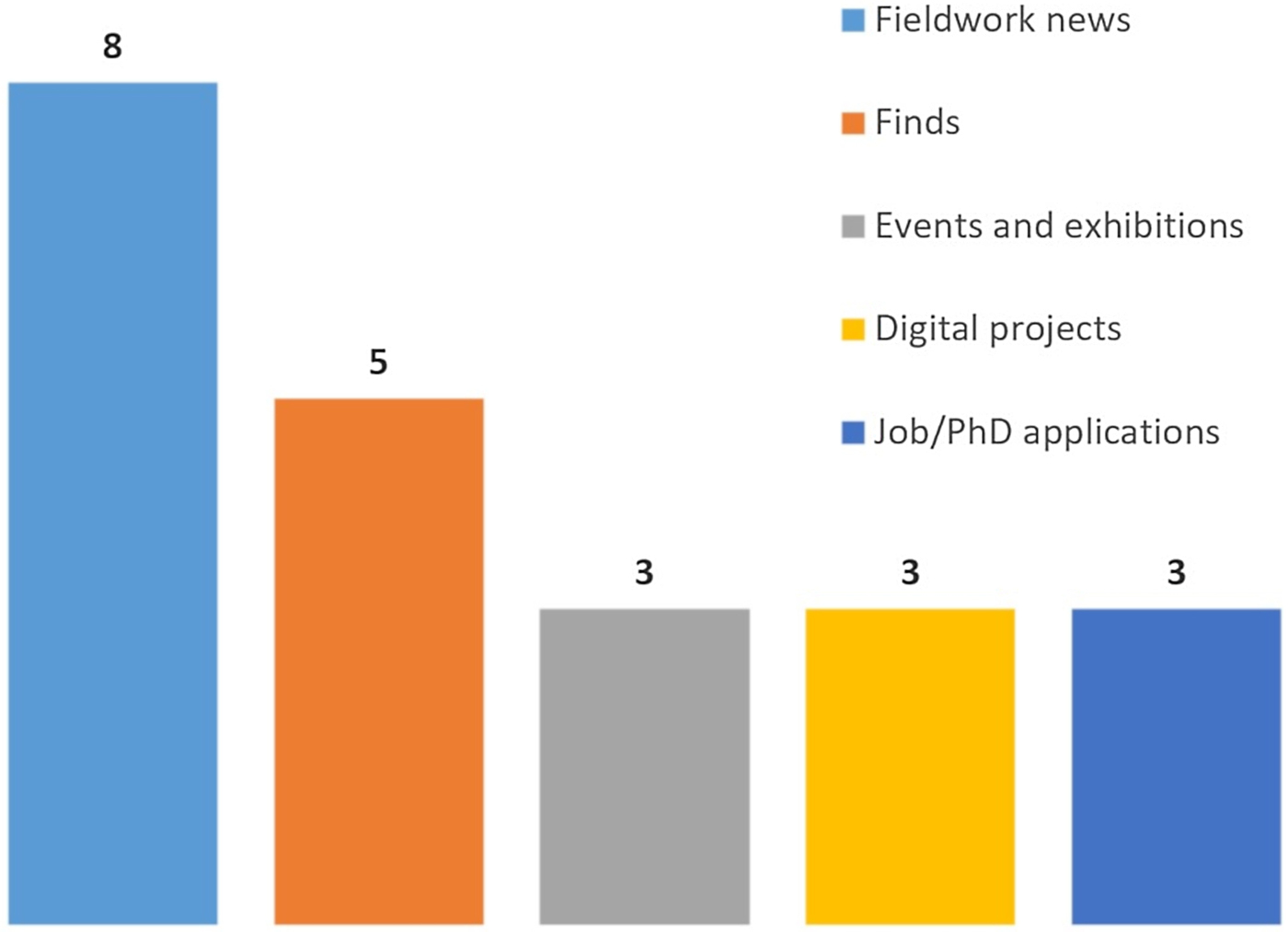

Archaeological fieldwork done by MOLA is another key activity for the organization, and it stands as the most common theme among MOLA's posts (Figure 4). The news portals, which broadcast the latest information about excavations, are the next most prominent subject of posts (Figure 4). MOLA's Headland Infrastructure page https://molaheadland.com, which represents a consortium of two major archaeological companies in the UK (i. e., MOLA and Headland Archaeology), is used to disseminate excavation news as well.

FIGURE 4. Breakdown of the themes of FB posts by MOLA: Fieldwork news, finds, events and exhibitions, digital projects, job/PhD applications.

Other shared posts represent webpages of a few specific digital projects, such as St. Paul's Cathedral VR project, the geomatic layers of London, and the interactive ArcGIS map of WW1 places where people once lived. They also link to other organizational webpages (e. g., universities, museums, municipalities) and offerings (e.g., exhibitions, archaeology job opportunities, etc.). As a marketing tool, Facebook is typically used by the organization to aggregate, broadcast, and disseminate information.

Occasionally, MOLA uses Facebook to post original content, with a specific focus on its educational program. There are only three cases (14% of all content) during my one-month observation period where MOLA used Facebook to share new content by uploading visual media (two videos and a photo) together with short textual descriptions (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5. Visual media posted by MOLA promoting its educational program MOLA Academy of Archaeological Specialist Training (MAAST).

These posts all relate to MOLA's recent educational program, MOLA Academy of Archaeological Specialist Training (MAAST), and are accompanied by the #MAAST hashtag. This suggests that the organization strategizes its posting activity and carefully chooses both content and the visual means to present it. Moreover, an uploaded image of teapot pottery was also accompanied by the #FridayFinds hashtag, a long-standing social media campaign on Facebook that was started in 2012, which involves the posting of a photo from the Museum of London online collections that describes interesting finds from various archaeological excavations. The #FridayFinds post suggests that MOLA aims to create durable social media campaigns, which form an important part of communication on Facebook. However, the effectiveness of these campaigns and their value for MOLA's community of users require detailed consideration. I offer such consideration below via scrutiny of Facebook's metrics for MOLA.

EVALUATING AUDIENCE REACTIONS TO MOLA'S FACEBOOK PAGE

To perceive the overall value of MOLA's content on Facebook, I took audience interaction rates on posts into account. These rates “can help monitor and evaluate the ‘success’ of social media posts, and represent useful measures when understanding what type of content drives higher engagement” (Malde et al. Reference Malde, Finnis, Kennedy, Ridge, Villaespesa and Chan2013:36). More specifically, Facebook users can provide reactions via three interaction activities on an organization's posts: liking, sharing, or commenting. Impacts can then be measured quantitively by counting actual numbers of likes, shares, and comments on posts, as well as qualitatively by looking into the nature of comments and the sentiments they convey.

I have evaluated all three activities in order to identify MOLA's most engaging type of content and to define its value to the audience. Liking can be considered the most simplistic and most common activity, and it tends to represent positive attitudes, endorsements, or basic interest from the audience toward the content. Impact analysis shows that all 22 (or 100%) of MOLA's posts gained likes from followers. Likes range from seven per post (the lowest) to 180 per post (the highest) with an average of 50 per post (Figure 6). Content sharing is another important audience engagement measurement, which relates not only to one's expressed attitude towards a post, but also to perceived social value, believing that content might be relevant to others and is worth sharing with them. The third user activity, commenting, is the least common, even though it can be considered the most valuable measurement in terms of understanding interrelations between the audience and the content.

FIGURE 6. Audience reactions in relation to specific themes found in MOLA's posts: fieldwork news (FN), finds (F), events (E), digital archaeology projects (DP), jobs/PhD positions (J); types of activity: posting (P) and sharing (S); and primary sources for shared content: MOLA's website (M: Mb – blog; Mc – career; Me – events), news portals (N), MOLAHeadland webpage (MH), digital projects’ websites (DP), others websites (O).

To understand which of MOLA's posts are most valued by the audience, I conducted a qualitative content analysis in relation to different types of content. First of all, I sought to evaluate general audience reaction to posts covering five thematic areas (Figure 6): information about archaeological fieldwork news (FN), presentation of research through descriptive stories of archaeological finds (F), promoting events and museum exhibitions (E), introducing digital archaeology projects (DP), and inviting people to apply for archaeological jobs or PhD positions (J).

Secondly, I drilled down into these thematic areas based on the Facebook activity types (posting vs. sharing) demonstrated by MOLA's audiences (Figure 6). In addition, I considered the nature of shared posts, including the primary sources of the shared information, as well as particular sections of MOLA's website that were often presented as the main sources of information. This evaluation of audience reactions showcases which archaeological content attracts higher public attention.

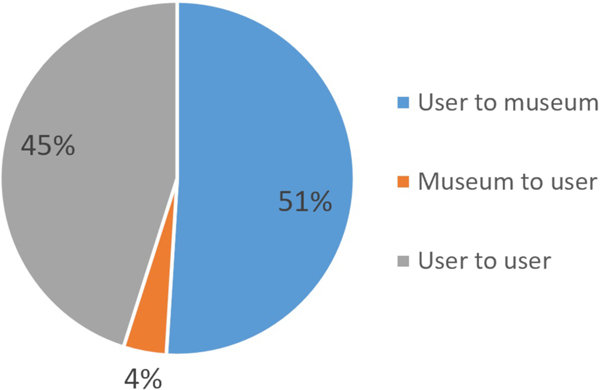

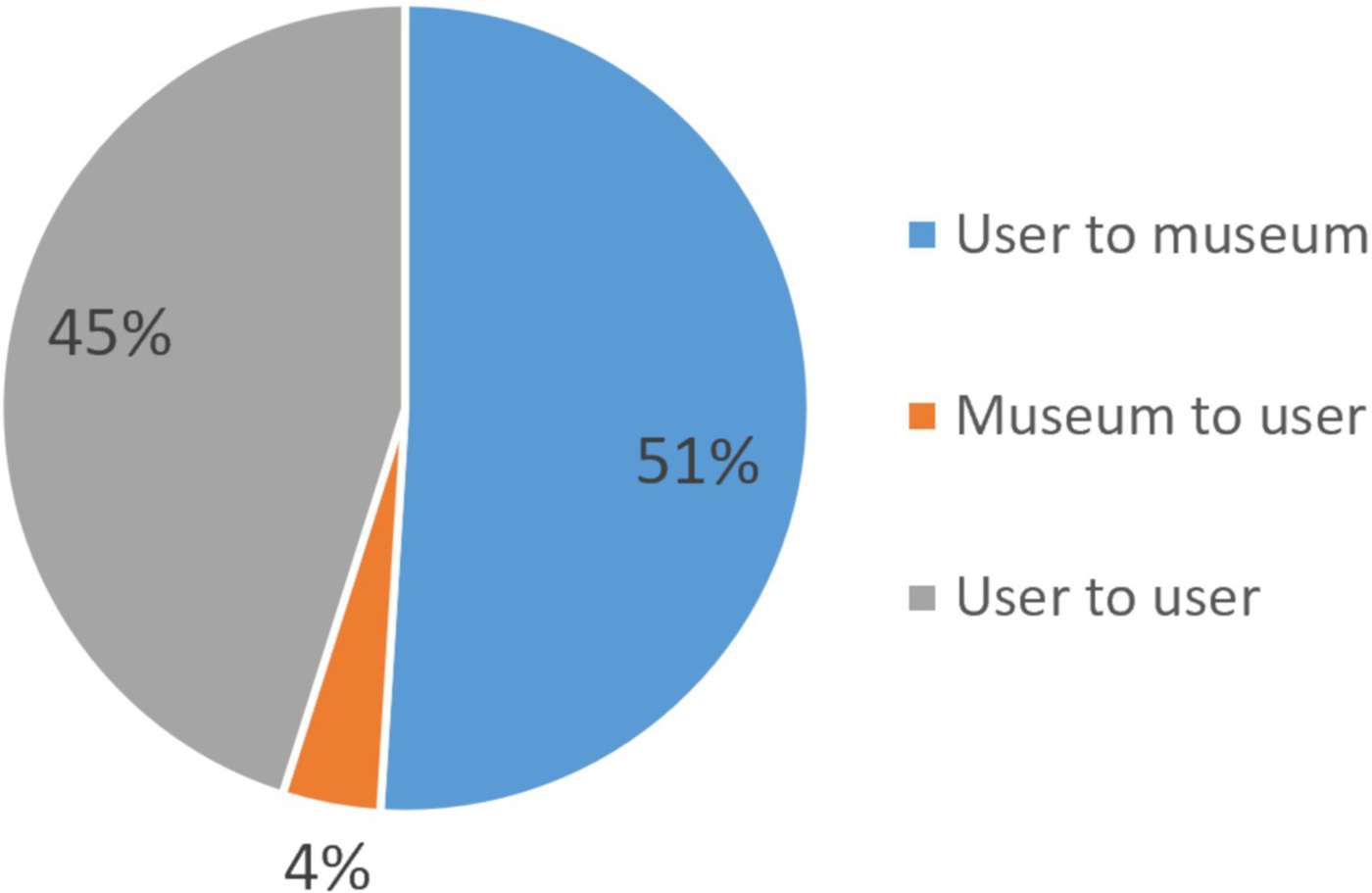

Furthermore, qualitative data and sentiment analysis were applied to users’ comments, seeking to provide deeper insights on the nature of conversations by identifying positive, negative, and neutral comments. Also, the direction of conversation was indicated by classifying Facebook comments as user to museum, museum to user, or user to user.

The post with the highest number of likes (180), which represents 1.3 percent of MOLA's total Facebook page community population, was also the one that received the highest number of shares (125), as well as the second highest number of comments (10) (Figure 7). The shared post links to MOLA's blog on its webpage and presents a digital archaeology project on St. Paul's Cathedral: a virtual reality reconstruction of the medieval cathedral, which was destroyed by fire in 1666.

FIGURE 7. MOLA's post representing the highest number of likes (180) and shares (125), as well as the second highest number of comments (10) during the observed period.

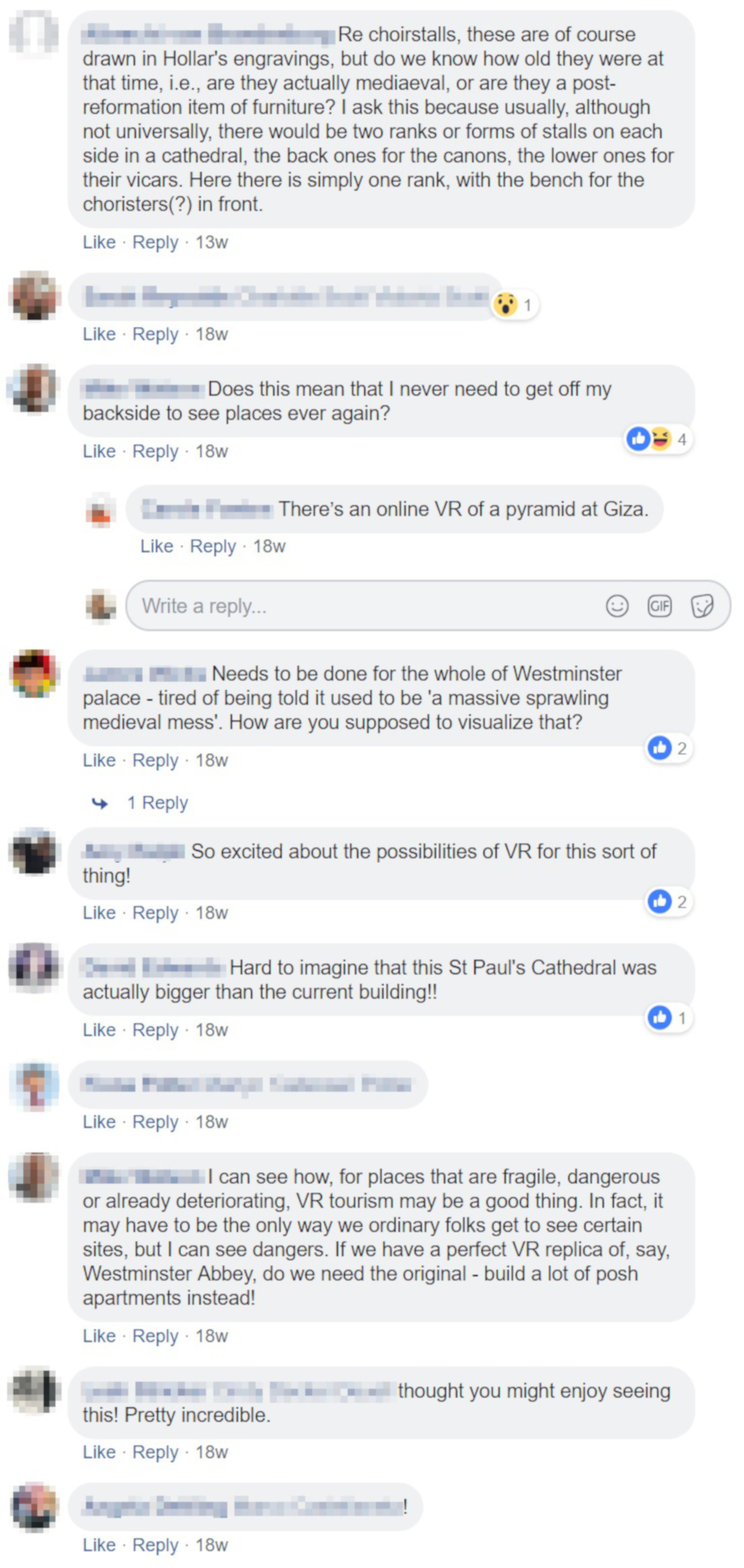

The majority of comments on the post can be described as neutral (5), with users merely tagging others to draw their attention to the post. One post also raised a question, encouraging reaction from other users regarding VR experiences in archaeology (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8. Users’ comments on MOLA's post on the St. Paul's Cathedral 3D project.

Three positive comments on the post expressed excitement about applying innovative technologies in archaeology to enhance visitors’ experiences. These comments describe the project as “pretty incredible” and “hard to imagine,” for example (Figure 8).

In contrast, a handful of negative comments offered concerns about the possibilities of VR, in some cases seeing it as “danger” to actual archaeological heritage (Figure 8).

It seems that information about digital archaeology projects posted on MOLA's Facebook page sparks higher user engagement with content. The discussion that evolved around St. Paul's Cathedral in VR suggests that it is not only enthusiasm about digital technology in archaeology that causes reaction but also concerns related to the technology's impact on “real” archaeological heritage. However, as all of the comments were posted by users (either user to museum or user to user) and none by MOLA, it is impossible to define the organization's position in this discussion.

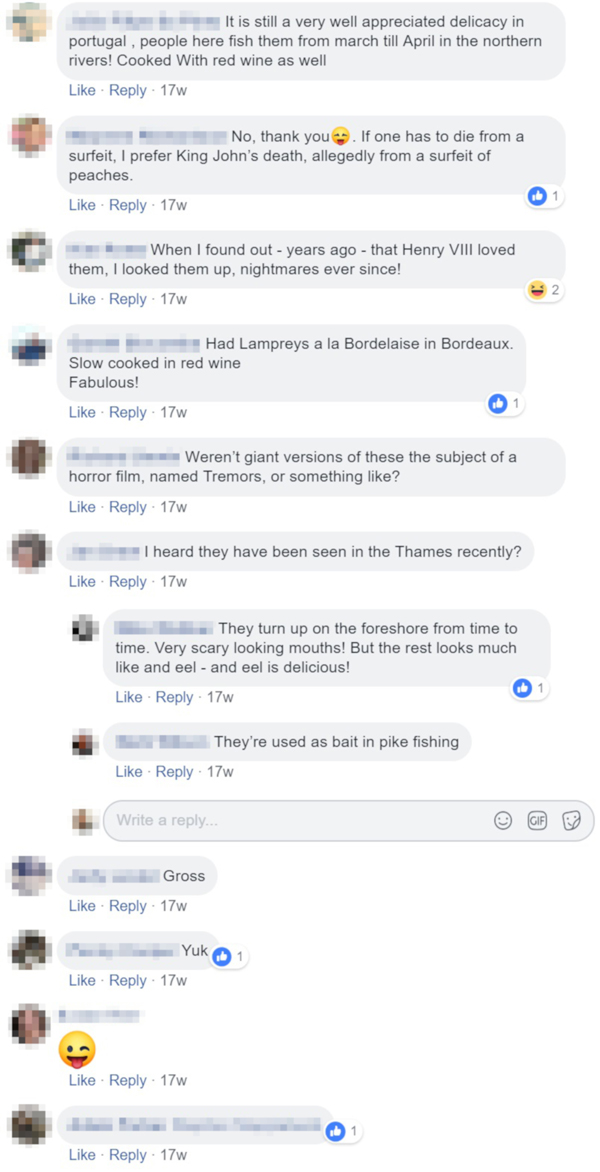

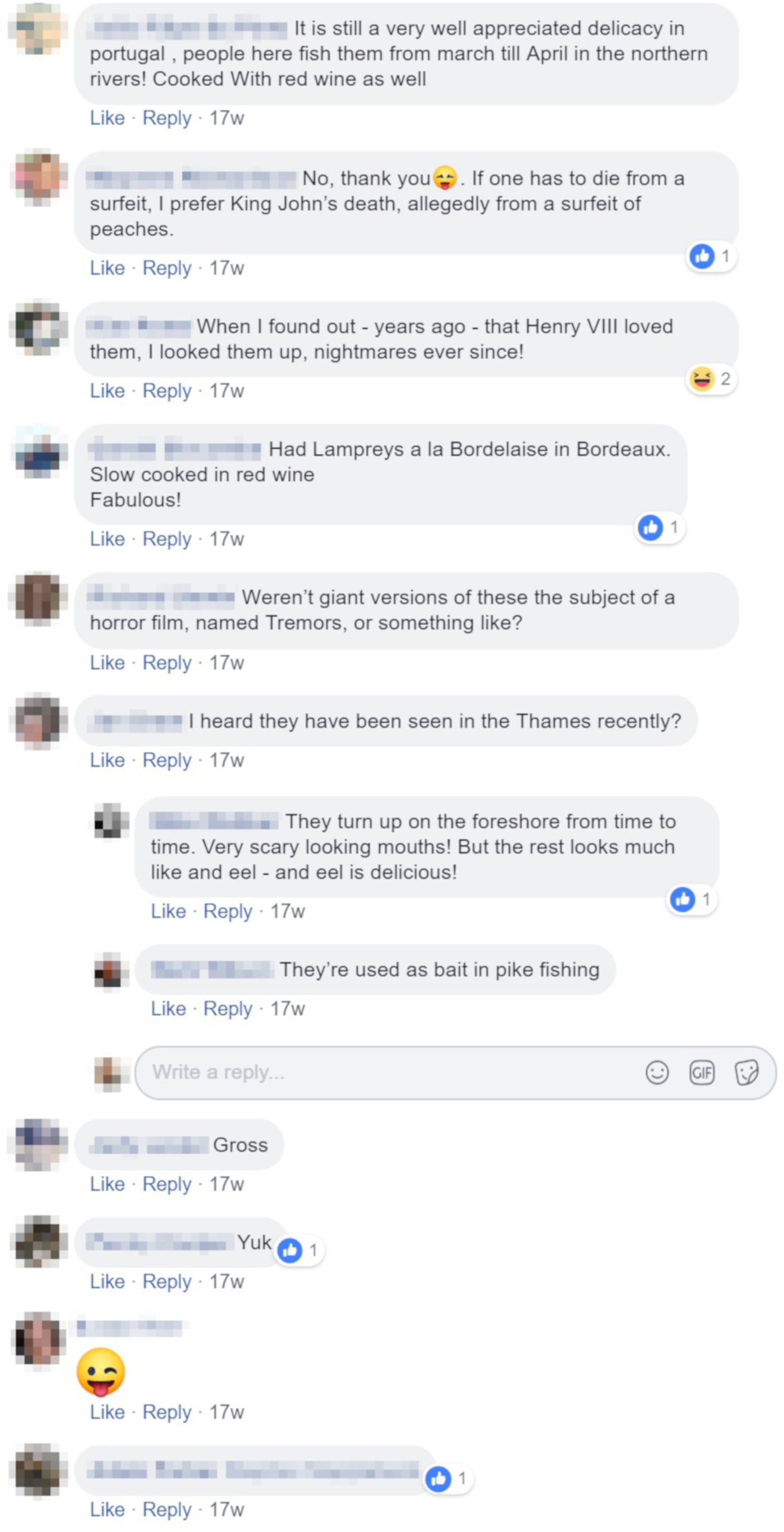

MOLA's most commented-on post—with 12 comments and the second highest number of shares (62)—also derived from MOLA's blog, and it presents an interesting story of Lamprey fish “teeth” finds (Figure 9).

FIGURE 9. The most commented-on post during the observed period, about finds of lamprey “teeth”.

The post sparked varied comments from community members, the majority of which were negative (6), but only in terms of expressing some sort of disgust toward the “delicacy,” even though usually they were presented in a humorous form. A few, however, expressed positive reactions (2), usually based on their personal experiences. Neutral comments (4) expressed curiosity toward the subject by posting questions and initiating discussion among community members (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10. Users’ comments on MOLA's post on lamprey finds.

The lamprey post shows the ability of the content to cause emotional reactions, suggesting that such emotional appeal should be considered a significant factor for higher audience engagement.

Another interesting observation around users’ metrics relates to the sources of information from which MOLA derives content. All three posts linking to MOLA's blog were among the top five most engaging posts, with two of them taking the first two positions in overall evaluation of audience reactions (Figure 6). It seems that MOLA's blog is of high interest to its audience and should be considered an impactful tool for audience engagement. While blogs are usually seen as solo channels for broadcasting to a targeted audience (Whitcher-Kansa and Deblauwe Reference Whitcher-Kansa, Deblauwe, Kansa, Kansa and Watrall2011), they are also useful for revealing the “human side” of the institution and its intent to engage interested publics in archaeological research (Walker Reference Walker2014). MOLA's Facebook page showcases that this social platform works effectively in promoting blog content and that users are keener to engage in discussion on the Facebook page rather than on the blog site itself.

In regards to fieldwork news (which is the most popular type of post by MOLA in terms of thematic coverage), from the perspective of the Facebook community, such posts do not seem to attract discussion. Even though they usually get a higher number of likes and a relatively higher number of shares, they rarely receive any comments (Figure 6).

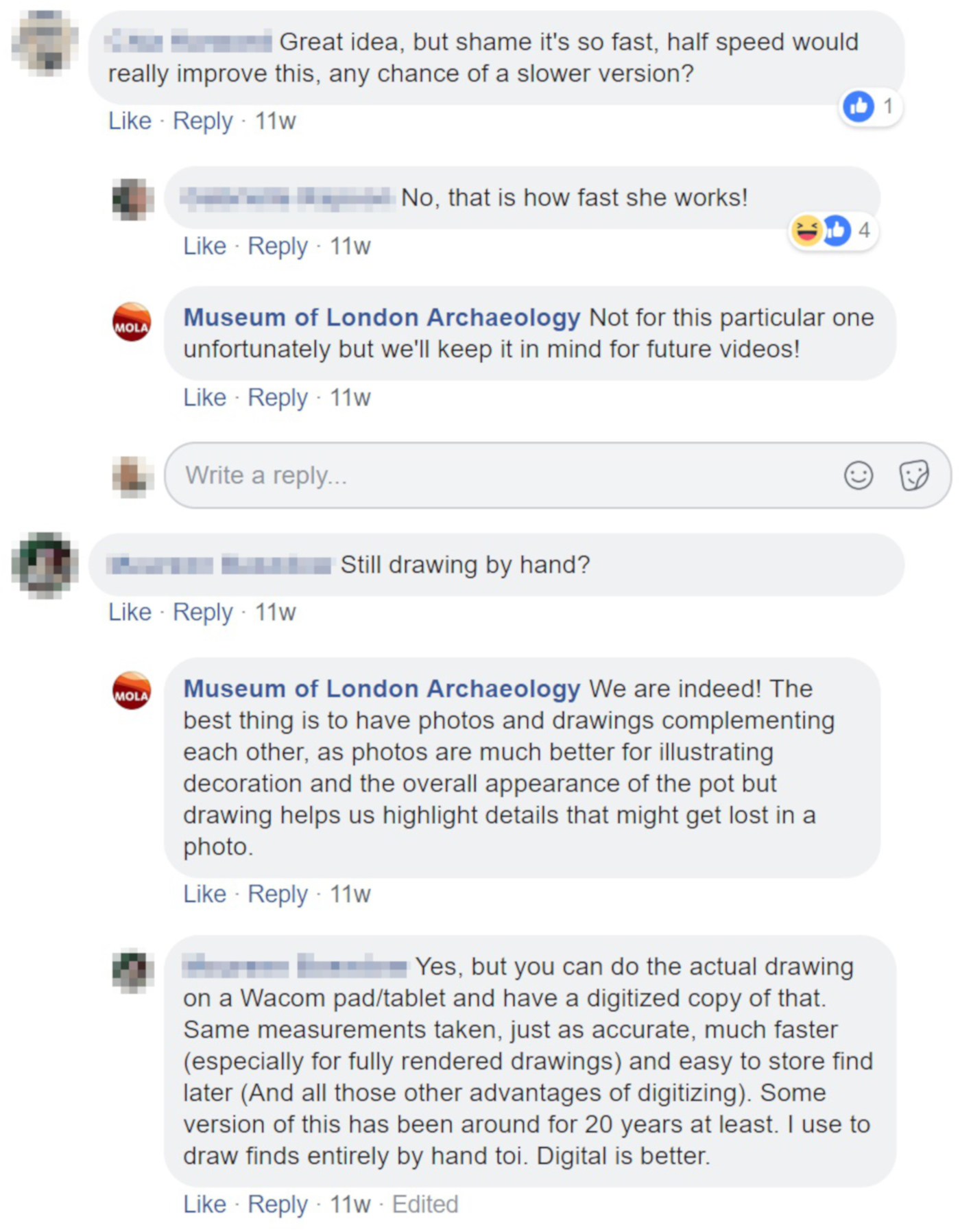

Information about jobs or PhD applications, as well as various events, are the least popular among MOLA's Facebook users. The same applies for original content posted directly to Facebook, which generally gets less audience reaction (Figure 6). On the other hand, of the three original posts generated by MOLA during the observation period, one post with a video related to the MAAST work received a relatively higher number of likes, shares, and comments (Figure 5). In fact, a discussion ensued between users asking questions, with MOLA answering them (Figure 11).

FIGURE 11. Museum-to-user interactions on MOLA's Facebook page.

This exchange represented the only time that MOLA was involved in a discussion with its Facebook page users. Otherwise, the vast majority of comments were user to museum or user to user (Figure 12). The relative popularity of this post highlights the importance of MOLA's participation in Facebook discussions in order to engage its community.

FIGURE 12. Main message directions for comments on MOLA's posts.

CONCLUSIONS

The creation of new content on Facebook always requires more effort for an organization and needs to be carefully considered and evaluated over the course of time. In MOLA's case, being more responsive was associated with higher audience engagement. Consequently, having a more active voice stands as an important factor in fostering community participation on Facebook. Yet, even though Facebook is a versatile platform, which could enable multiple kinds of interactions, it seems that for MOLA it primarily serves as a broadcaster of information, helping to share content from different websites. In fact, one of the main shortcomings identified by this review is the lack of MOLA's voice in the discussions, as most of the comments seem to be between users. Since the organization has interesting and engaging content posted elsewhere (e.g., on its website and blog), Facebook offers a medium through which this content can be discovered by wider audiences. At the same time, MOLA's Facebook page is appreciated by the community as a place where they can participate in discussion.

There was no strong correlation between thematic content and higher audience engagement, even though information about archaeological finds, digital archaeology projects, and fieldwork prompted active engagement relatively more frequently than information about events or job positions. On the other hand, some of the primary sources of information for posts (e. g., MOLA's blog) were strongly related to higher community engagement. Finally, there was no indication that long-lasting social network campaigns (e. g., MOLA's “Friday Finds”) or other types of original content posted uniquely to Facebook are currently perceived as more valuable by the community.

MOLA's Facebook page showcases how an archaeological organization performs its communication and dissemination on a day-to-day basis, and it provides insight into possible implications for successful practice on social network sites, as well as into possible reasons for failure. Such observations may help other similar archaeological organizations performing under the “marketing frame,” to be more vigilant of their social networking activities, as well as the content they share and its value to the community.