Any comprehensive account of the development of the heritage system in Albania (Figure 1) needs to review the profound impacts of two particularly important historical moments in the last 70 years. The first is the end of World War II, which marked the establishment of a communist sociopolitical system dominated by a centralized state economy, egalitarian ideology, and the disappearance of private property and free initiative. The second is the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the series of events in the 1990s resulting in the social, political, and economic transformations of the postcommunist society during the last 30 years. These two historically important landmarks, both in the second half of the twentieth century, have dramatically changed the development of Albanian society and explain many of its features, uncertainties, trends, and its narrative of itself, among other things. Also useful to understanding the complex relationships of contemporary Albanian society with its own past are the facts that (1) Albania, which gained its independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1912, is a relatively young independent state with just over 100 years of history as a political entity; and (2) Albania is embedded in the Balkan context, with its complicated ethnic identities, problematic relationships, changing boundaries, and economic underdevelopment compared to neighboring central and western Europe (Abrahams Reference Abrahams2015; Vickers Reference Vickers2001).

FIGURE 1. Map of Albania and the Balkans.

Over the course of the last century, competing narratives of the past that have been carefully crafted by the nation states in the Balkans have necessarily focused on the definition of ethnic and cultural identities, the documentation of their deep roots in the distant past, as well as their multiple connections with living populations. Albania is not an exception. The consolidation of the communist government in power following World War II marked the beginning of the construction of a system of archaeology and heritage that was generously funded and supported until the late 1980s in order to provide scientific evidence for the nationalistic agenda of the new state. An entire generation of young scientists and heritage operators was created, and they made some impressive achievements in both research and the preservation of heritage. It is thanks to the concerted efforts of these professionals and the new state-funded institutions (such as the Academy of Sciences, the Institute of Archaeology, the Institute of Folklore and Popular Culture, and the Institute of Cultural Monuments) that unprecedented progress was made in the understanding of the prehistoric and historic past (Cabanes Reference Cabanes1998).

The profession often grew alongside the state-sponsored agenda. The heritage system proved to be very effective in identifying, studying, and preserving both tangible and intangible expressions of the country's heritage. Legislative acts and research and heritage management procedures were adopted and progressively improved, providing the basis for a new experience within the heritage community (Papa Reference Papa1973). Until the beginning of the 1990s, the centralized government and rigidly planned economy of the socialist state, based on public ownership of almost everything, made it easier for the heritage system to control, coordinate, and implement preservation practices on heritage assets. The planned nature of all development by the state sector, the limited scale of developments, and the total absence of free initiative exercised limited pressures on heritage management and archaeology. Following the model of the sociopolitical structure, the heritage system was also designed as a highly centralized system. Not only did national organizations represent the highest levels of professional resources, but they were also empowered with the authority to exert their control and influence everywhere in the country. This ability to effectively operate everywhere assured a high quality of decisions and interventions but also coherence and standardization of procedures that would have otherwise been difficult to achieve, particularly in the remote communities. On the other hand, the narratives of the past were strongly ideological and intended to legitimize the central political power and consolidate the nation state. Thus, they were consistently used to demonstrate the historical basis of the need for isolation from the world and consolidation of the internal centralized power (Galaty and Watkinson Reference Galaty, Watkinson, Galaty and Watkinson2004:8–12; Galaty et al. Reference Galaty, Stocker and Watkinson1999).

Only 45 years after the end of the World War II, in the early 1990s, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent collapse of the communist system marked another moment of radical social change in Albania, as in the rest of the Eastern Europe. The basic principles of economic activity of the former socialist society, which was based on state ownership of every means of production, now opened to private property and free initiative. Since then, international cooperation and rates of development have proven to be unprecedented. The pressure on the heritage sector from infrastructure, demography, energy, and urban developments has increased rapidly. Social unrest, sophisticated and highly interconnected criminal activities, and the demands of the population for a much higher standard of living have created new challenges. For the second time in less than 50 years, dramatic social, political, and economic changes have occurred. The country's constitution and entire legal framework has had to be redrafted. This process of transformation, which included the heritage system, has brought with it the risk of ignoring everything positive built by society in the recent past, as is evident in the postcommunist era. As is any period of social change, the post-1990s were exciting times. In times of change, the maintenance of cultural identity becomes even more important, and heritage and research institutions changed little because of their already consolidated tradition and their widely perceived role in preserving national identity. The collapse of the structure that kept former Yugoslavia together in the Balkans made the issue of national identities even more relevant in the face of the relationships of the ethnic groups (Albanians, in our case) with the wider world (Vickers Reference Vickers1998). The sociopolitical context in which the heritage institutions were operating had changed and was developing rapidly.

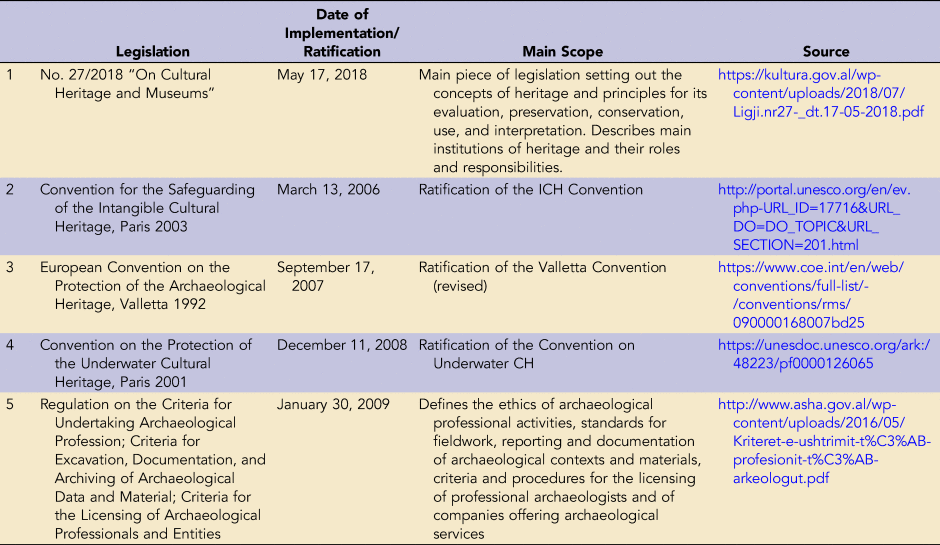

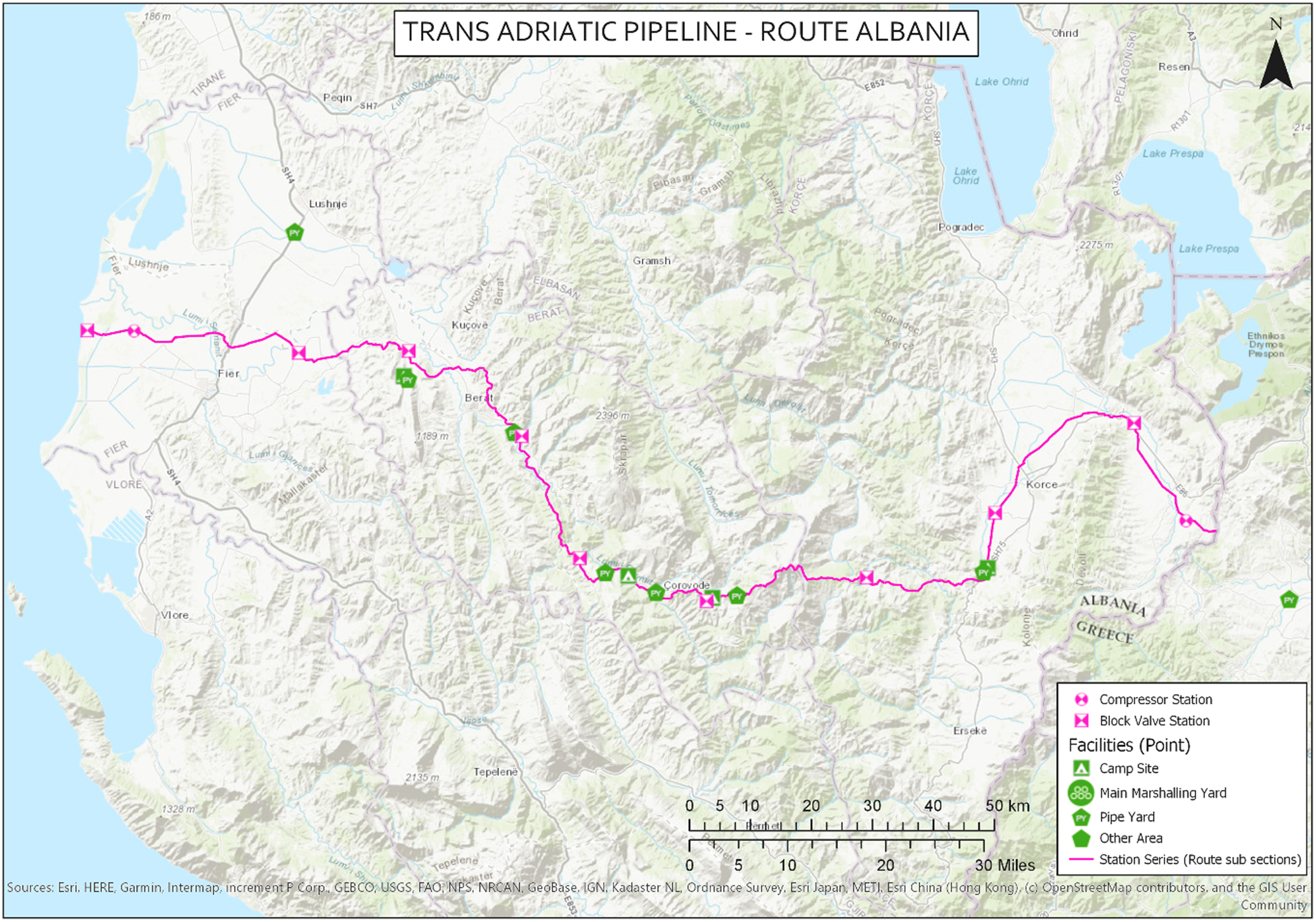

These new challenges required rapid action. The first of the responsive actions came in 1994 from the field of legislation. A new law on cultural heritage was approved that kept the same centralized system of heritage, with the same hierarchy of institutions and professional figures, even though the emergence of the private sector and the decentralization of the administrative power demanded stronger and more independent local heritage institutions in the different regions of the country. The need for a new heritage law that responded to rapid developments outside the discipline soon became evident, and the new law was presented about 10 years later. It was approved by the Parliament in 2003, with substantive amendments introduced in 2008 and 2011. Subsequently, a new Law on the Cultural Heritage and Museums was adopted by the Parliament in 2018 (Ligji nr. 27/2018 Për Trashëgiminë Kulturore dhe Muzetë, Ministria e Kulturës, Tiranë, 2018). The three new laws and several amendments of the last 25 years are only one aspect of the changes in the heritage system in Albania (Table 1). These changes effectively show the constant need for regulations and procedures that will bring the heritage sector up to speed with other sectors of Albanian life and international standards and also illustrate the underlying difficulties of the system and its resistance to adequate change.

TABLE 1. Main Current Heritage/Archaeology Legislative Acts in Albania.

Here is not the place to provide an in-depth analysis of the current legislation on Cultural Heritage in Albania. It is important, however, to mention that the trend is progressively toward creating an effective decentralized system of heritage (Table 2). The new system is required to cope with the local dynamics of historic centers and archaeological parks so as to be responsive to the rights and needs of the multiple stakeholders; to provide protective and sustainable development measures in accordance with other planning needs and mechanisms; to be respectful of human rights, minorities, and other vulnerable groups; to set guidelines for more dynamic management practices of heritage; and generally, to be better aligned with the needs of contemporary society.

TABLE 2. Main Institutions of Archaeology and Cultural Heritage in Albania.

THE HERITAGE DISCOURSE

Before I discuss the mitigation procedures and the role that mitigation plays in the heritage practice in Albania, it will be useful to describe the state of the heritage discourse in the country. The concepts of heritage today inherit much of their structure from their formative period of the twentieth century, as briefly outlined above. Heritage is mainly material, monumental, and highly aesthetic; it is the backbone of national identity; is almost totally intellectual property of academics and professionals such as archaeologists, historians, ethnologists, and conservation architects; and can be offered as a product to the general public and the tourism sector. Heritage occupies a special place in public debates in Albania, and the public's interest in heritage issues has grown in the recent years. Civic organizations and individuals have contributed to making heritage relevant and to holding cultural institutions accountable for its preservation, management, accessibility, and presentation. There are several points that characterize this discourse:

(1) Heritage appears as very important for the documentation through material evidence of the national identity of the Albanian people.

(2) Heritage preservation and management must aim at properly keeping the material reality of the past and passing it on to future generations.

(3) Heritage is valuable because it traces Albanians back in time and confirms their autochthonous character and rights to their territories.

(4) Heritage is defined and its values are assessed by professionals (even those individuals who are not heritage professionals try to claim expertise in order to gain credibility).

These features are, not surprisingly, very similar to what Smith (Reference Smith2006) has considered “Authorized Heritage Discourse,” and in many ways, they reflect an agenda that is imposed by the traditional/institutional heritage discourse. My point, however, is that it seems that this agenda is uncritically embraced by contemporary debate in Albanian society, even when accountability is requested from the state cultural institutions.

THE “MITIGATION” CONCEPT

“Mitigation” is a word with no direct translation in Albanian. It is also not a concept that is explicitly represented in Albanian legal literature on cultural heritage. It is, however, implicitly intended in several procedures, particularly those that deal with large development projects. The first appearance of these procedures is related to the Law on Cultural Heritage, adopted in 2003 (Ligji për Trashëgiminë Kulturore. Ministria e Kulturës, Tiranë, 2003). Prior to 2003, “common sense” was used to mitigate adverse impacts on heritage assets. The norms of “common sense” were particularly effective before the 1990s, when the state-dominated economy made it easy for state institutions to coordinate actions and plan interventions of different kinds on the ground. This coordination became more difficult with the introduction of private development initiatives, conflicting interests, and decentralization of planning authorities. For these reasons, the need for clearly stated legal procedures to guide the cultural institutions became crucial for the purposes of mitigating impacts. In the law of 2003, however, these procedures were neither clear nor complete. The Council of Europe and the European Convention for the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage, adopted in Valletta in 1992, exerted an important influence on the promotion of the concept that the “polluter pays” in the Albanian law of 2003, even though it was only ratified in 2007 by the Albanian Parliament. This premise alone, however, was not a guarantee for a successful implementation of the principle. The necessary institutions, roles, and responsibilities were still missing, or largely ineffective. Amendments to the law in 2008 were intended to fill the gap.

These same reasons were in large part responsible for making another important piece of the European Union legislation almost ineffective—namely, the Directives on the Environmental Impact Assessment, which were drafted in 1985 with subsequent amendments (Directive 2011/92/EU). Even though these directives were reflected in the national Environmental Protection Law (Ligji për Mbrojtjen e Mjedisit, 2009, https://gzk.rks-gov.net/ActDetail.aspx?ActID=2631), the procedures for implementing this law with regard to cultural heritage have failed to make useful reference to the Cultural Heritage Law. These two ministries, the Ministry of Environmental Protection and the Ministry of Culture, have been operating for a long time in a parochial, unintegrated fashion, with no proper cross-referencing between them. In the last three years, however, we have been noticing some encouraging signals of breaking the isolation in addressing both environmental and cultural heritage issues under an overall national planning policy.

The legal framework designates the National Council for Archaeology and the National Council for Restoration as the central decision-making bodies that assess, approve, and enforce, through the permitting process, the relevant mitigation measures. As expressed in the law since 2003, mitigation, in almost all cases, has meant avoidance of the heritage property by development projects, documentation through (for instance) archaeological excavation, or the imposition of conditions to the implementation of the development project. The law also stipulates that the costs of the project modification are to be covered by the developer. There were no clear procedures for assessing the value of the heritage property or the impact of the development project on any significant value. There were no provisions for assessing the feasibility of the proposed mitigation, and there was no way out in cases when this was not financially feasible for the developer. Moreover, there was no procedure for any legally binding agreement between parties for the implementation of the approved mitigation. The laws of the postcommunist era still carried the mentality and the basic concepts of the recent past into the new socioeconomic context. They displayed the overruling power of the state institutions over matters of mitigation and the lack of consideration for the rights of the other parties to discuss the feasibility of the mitigation measures or alternative solutions. Because of the residual inherent belief that the decision of the central cultural institutions is the only professional representation of the law, heritage decisions are often made in isolation from other aspects, such as the legal or financial implications they might have on other state institutions or private entities. In this aspect alone it is clear that sociopolitical change is not an easy process and does not come at a clear-cut moment in time. The trajectory of change goes through transition periods characterized by mixed elements of the past and the present, whereas the future is not always clear or predefined.

Other aspects of the mitigation practices in Albania of the last decade include the provision that the central institutions, such as the Institute of Cultural Monuments of the Archaeological Service Agency, are tasked with monitoring and reporting on the implementation of the approved mitigation measures. These institutions, however, do not have the human and infrastructural resources to complete this task properly. In practice, accountability for failure to perform as decided and approved by the decision-making bodies is uncertain. Procedures for accepting well-implemented mitigations are not clearly defined. The independent assessment of whether the mitigation has avoided certain problems to heritage assets, while creating others, is almost never done. For several years, it has become obvious that the very concept of mitigation and its legal articulation in the country's legislation is obsolete, at times extremely rigid, disrespectful of the multiplicity of voices and interests around the heritage sector, incomplete, and difficult to follow through all its phases. A need for alternative solutions has been growing steadily, some of which I will discuss through the examples that follow.

In a recent publication, Thomas (Reference Thomas2019) argued that the use of the term “mitigation” in a development-led archaeology context is not appropriate. Instead, the concept of providing a benefit of one kind to make up for a loss of a different kind could be better described as “off-setting” or “compensation,” somewhat similar to the standard terminology used in the environmental discipline. Even though I agree with this argument, for the sake of consistency with the rest of the contributions in the volume, I will continue to refer to “creative mitigation.”

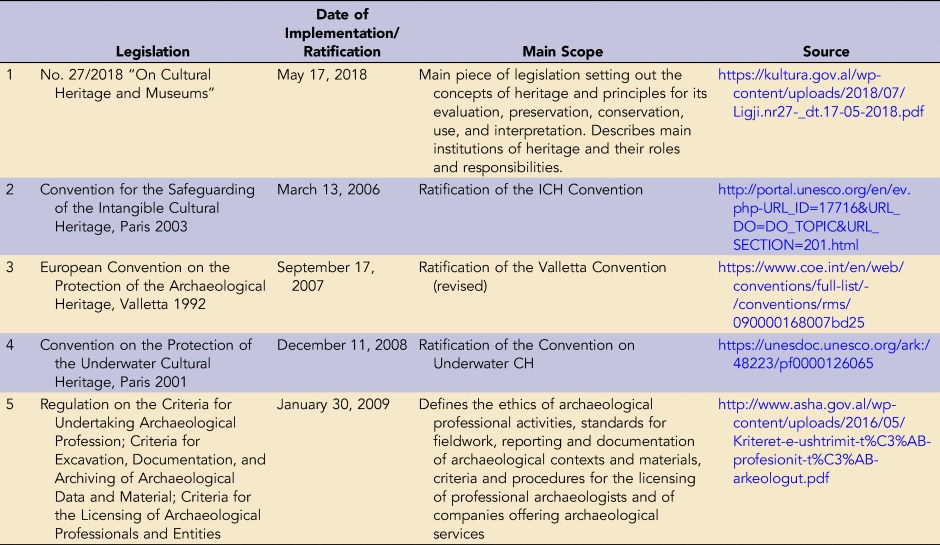

THE TRANS ADRIATIC PIPELINE PROJECT

The Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) is a large-scale development project that aims to bring Caspian natural gas to Europe. TAP will connect with another pipeline (Trans Anatolian Pipeline) on the Turkish-Greek border and will cross northern Greece, southern Albania, and the Adriatic Sea in order to emerge in southern Italy to join the European gas network. It crosses Albania from east to west (Figure 2) along a corridor more than 215 km long and 40 m wide. This right-of-way of the project represents the area with more direct impact on the territory; however, the impact of the overall project goes beyond this linear feature and includes the construction of many access roads and other infrastructure such as yards, camps, and disposal areas, which are necessary for the construction and long-term maintenance of the pipeline. As such, the project crosses a variety of environments and landscapes, including some areas well known for their archaeological potential and previously documented long-term human settlement. During the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) studies before the implementation of the project, the valleys of the rivers Devoll and Osum, the large plateau of Korça in the southeast, and the western lowland of the country around the major urban centers of Apollonia, Dimal, and Berat were assessed as critical areas with high archaeological and heritage potential.

FIGURE 2. Map showing the passage of the TAP gas pipeline through southern Albania.

TAP is committed to meeting high international standards with regard to protecting and promoting the environment, local communities, and cultural heritage, and it has adopted European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) standards and requirements for the measurement of its performance (EBRD 2014). This presented a welcome precedent for the Albanian heritage institutions and the heritage community because it created the possibility of adopting higher standards than those required by the national legislation through a well-funded, large-scale development project.

The very definition of “cultural heritage” in the EBRD Performance Requirement (PR) No. 8 is much wider than in the comparable Albanian legislation. It embraces “resources inherited from the past which people identify, independently of ownership, as a reflection and expression of their evolving values, beliefs, knowledge and traditions” (EBRD 2014:PR8:point 6). This opens the way for identification and protection of heritage that is locally recognized as such (even if not registered in the national heritage list), including intangible heritage and heritage of the recent past. The project was also a good test for the Albanian heritage institutional system and its readiness to manage a dynamic project of TAP's kind, size, and complexity. In addition, it was a test of the heritage legislation that had gone through numerous changes and amendments and an opportunity for lessons learned for the future.

In the framework of the ESIA study for TAP, over 150 cultural heritage sites and areas of high archaeological potential were identified, as well as significant intangible heritage sites (Trans Adriatic Pipeline 2016). These data informed the process of route selection for the pipeline with the goal of avoiding archaeologically sensitive areas and creating buffer zones around the known cultural heritage sites. However, the potential for chance finds, particularly in areas such as the Korça Basin or the Osum valley, remained high. A chance find procedure—which started with the constant monitoring of all ground-breaking activities, continued with the implementation of the Stop Work Protocol, and ended with the involvement of the relevant national authorities for approval of the mitigation measures more appropriate for each case—has been continuously adopted, as indicated by TAP commitments. Fieldwork between 2016 and 2018 met and exceeded expectations laid out in the ESIA document, with the discovery of several important sites. Mitigation measures discussed and approved by the national authorities and then implemented by TAP sometimes required thinking “outside the box” of the incomplete legal framework of the country. Even though avoidance and documentation were the only requests made by the Albanian National Archaeology Council, TAP moved well beyond those requirements to involving stakeholders in the process of heritage identification and ways and degrees of protection, as well as informing them systematically about the main discoveries, and other educational activities. Only some examples are discussed here.

During the preparatory work (opening of the right-of-way) before the opening of the deep trench for the pipeline near the village of Turan (in the center of the Korçë Basin), the remains of several burials were discovered. The discovery caused the construction to stop immediately and led to the subsequent assessment by the archaeologists engaged in the project and the Archaeological Service Agency. The assessment of the nature and extent of the site showed that it represented a complex site with multiple chronological components and that it most likely extended well beyond the limits of the right-of-way secured by the project. Avoidance was not easy for the developer to adopt because of efforts related to land acquisition and potential long delays (and the relative costs) to the construction operations. A statement of fieldwork methodology was prepared and presented to the National Archaeology Council for the rescue excavation of the section of the cemetery that coincided with the trench line of the pipeline (an almost 5 m wide trench with a depth of over 2.5 m). The documentation and removal of the burial finds was considered appropriate so that the trench, cleared of archaeological remains, could become available for laying out the pipe.

The National Archaeology Council had not often found itself facing decisions of this kind. It accepted the argument that avoiding the site would be an impractical and costly choice. The documentation and study of the cemetery was instead considered important for the public interest because the site had the potential for increasing the knowledge and understanding of the burial customs and social structures of the late prehistoric communities of this part of the country. However, the excavation of only the trench section of the cemetery (Figure 3) somewhat diminished the “public interest” of the excavation/documentation operation. If only the 5 m wide trench were investigated, questions of the sample size of the excavated cemetery would be raised and its representativeness would be questioned. It would also be difficult to get a sense of the full periods of use of the cemetery with this option. Consequently, a more balanced proposal was made to the developer. The proposal agreed to take “avoidance” off the table, as a very costly option for the developer. It also agreed to proceed with the urgent rescue excavation of the trench line, allow the construction team to lay down the pipe, and avoid disruption of the construction process (also very costly for linear projects of this kind). The developer, however, was asked to return to the site after the pipe was laid, with the goal of investigating the remaining area of the right-of-way acquired by the project.

FIGURE 3. View of the excavation of the trench line (5 m wide) at the cemetery of Turan in the Korça area (southeastern Albania). The fenced area with the orange mesh is a segment of the TAP's right-of-way (48 m wide).

This option was implemented with the agreement of all parties and proved to be the right one (Figure 4). Several periods of use of the cemetery were discovered by excavating the area outside the trench line. A large group of objects of material culture and their symbolic use in funerary contexts have enriched the analysis. Many important paleodemographic data have informed the reconstruction of the life of the communities that used this site as burial ground for their dead for a long period of time.

FIGURE 4. View of the excavation of the right-of-way (fenced area with orange mesh 48 m wide) of the TAP project (trench line is backfilled) at the cemetery of Turan in the Korça area (southeastern Albania).

Because it is near the modern village of Turan, the cemetery (or at least some human burials) had been found previously by the residents during their agricultural activities. Several myths and historical narratives were connected to the cemetery in the community. Since no one from the village has been able to claim any direct descendance from the individuals represented at the cemetery, the community had a vivid interest in finding out who these people were and how long ago they had been buried. Furthermore, oral histories revealed that a little church once stood in the area of the cemetery, and the archaeological team was asked to confirm this fact. Another interesting research question was put forward by members of the local community: where was the settlement of the people buried in the cemetery, and was it true, as the historical narrative indicated, that an epidemic disease had been the reason for its abandonment? This was a unique situation in which the stakeholders could not only have a say in the process but also influence the research agenda of the archaeologists. TAP's cultural heritage team enthusiastically embraced these questions and is now analyzing the rich data collected during fieldwork. Discussion of the results with the local communities is part of the next steps of the project. Mitigating the impact of the pipeline on the site at Turan proved possible due to a flexible and creative approach that was based on a careful evaluation of values, the nature of the impact, the integration of stakeholders in the process, and the feasibility of the approved mitigation.

The same approach was also taken in several other chance finds of the TAP project, including the case of the discovery of a large Neolithic settlement in the village of Dërsnik in the Korça region (6 km to the south of Turan), an early medieval cemetery immediately south of the World Heritage Site of Berat, and a late Antique and medieval settlement near the village of Fushë-Peshtan in the district of Berat (Figure 5). In this last case, the discovery of numerous remains of walled structures made it impossible for the trench line to go through the site, so realignment of the trench was necessary, and this was possible due to construction techniques creatively employed by the construction contractor within the right-of-way. The well-preserved structures of this rural settlement located on a steep slope overlooking the Osum River valley brought about a lively discussion on their conservation and presentation to the public. Several serious challenges, however, were highlighted during the discussions, the most important of which was the difficulty on the part of the state institutions in identifying resources for continuous maintenance and management of the site after conservation. The failure to find alternative sustainable solutions to the long-term preservation and management of the site led to the decision to backfill the site and reinstate the area with the addition of erosion control measures carried out carefully by TAP.

FIGURE 5. Aerial view of the site at Fushë-Peshtan, Berat District (central Albania). Yellow lines indicate the right-of-way (48 m wide), whereas the blue lines show the rerouted trench for the gas pipes (approximately 8 m wide).

A different approach was taken on another site on the western coastal plain of Albania. The remains of brick-and-tile kilns were discovered in a large area that was to be used for the construction of the compressor station. These kilns were part of a production center used by the local villages during the collective farm system from the 1960s to the beginning of the 1990s. The collective farm needed building material not only for the auxiliary rural structures (such as storage facilities, temporary shelters, and workshops) but also for the new housing required for the growing numbers of families who were added to the farm over the years. There are indications that the production center distributed bricks and tiles to several neighboring farms so that some additional income would be secured for the community. Ethnohistorical research collected local memories and photographic documentation of the work processes at the center, including the location of sources for raw materials and fuel, production capacities, and the number of people employed during the nonintensive agricultural seasons.

The National Archaeology Council requested the excavation and documentation of all the remains of kilns in the construction site of the compressor station. The goal was to reconstruct the scale of the production center, the typology of kilns used, and potentially, the pattern of expansion of the production center and its spatial organization. The developer could remove the remains after proper documentation because deep excavations were required for the construction of the station and stabilization of the ground. Both parties, however, agreed that two kilns (one for bricks and one for tiles) would be reconstructed (Figure 6), based on local knowledge and materials. The reconstruction will be displayed in the park area in front of the administration offices of the station with an interpretive panel that describes the site, its history, and its transformation from one traditional tile/brick production center into a gas compressing station that will transport gas offshore through the Adriatic Sea to southern Italy.

FIGURE 6. Reconstruction of a twentieth-century brick kiln from the site of the TAP compressor station in Fier (western Albania).

HYDROELECTRIC POWER STATION PROJECTS

In the last 10 years, there has been an increase in small-scale energy production initiatives in Albania, using mainly the power of running water. This trend has been strengthened by government policies in the energy sector, which seek, on one side, to stimulate the production of energy from renewable resources, and on the other, to provide a local solution to the growing internal demand for energy consumption. As a result of these developments, almost every governmental agency is faced with an unusually large number of requests for approvals of projects that intend to use, eventually, the running water of every stream, large or small, everywhere in the country. Central cultural heritage institutions face the same pressure for approving cultural heritage impact assessment reports required by planning authorities, alongside approvals of Environmental and Social Impact Assessments. The National Archaeology Council expresses discontent with the systematic spread of this kind of project almost everywhere, fearing a diffused impact on the ecosystems (even though the environmental agencies have always approved the projects) and on the natural and cultural landscapes, often in areas where no other projects could be developed. Nevertheless, there is no legal basis for the National Archaeology Council to not approve projects that are legally compliant and in remote areas with no direct impact on archaeological or cultural heritage resources. In fact, until the very recent Law on Cultural Heritage and Museums of 2018, the concept of cultural landscape was not present in the legislation, providing no effective arguments against these projects.

The need for thinking “outside the box” was again obvious as project proposals began to be introduced. Public assets were being put at the disposal of developers, and little was going back to the local users and real owners of these resources. The impacts on natural and cultural landscapes were not being mitigated, and the legislation was inadequate to impose—or even discuss—any reasonable mitigation measure. The Ministry of Culture acted by approaching all of the developers individually and providing them with a list of needed interventions on monuments and sites in and around the areas of the proposed projects. They were asked to voluntarily decide if, where, and to what degree to contribute, as a way of giving back to the communities a portion of what was being taken.

The results of this approach were stunning. Almost everyone agreed to do something, and in many instances, the developers took pride in undertaking conservation, maintenance, or presentation projects for the local cultural sites. The developers probably found this activity a way to build bridges with local communities that, in many cases, were unhappy with the sudden change in—or disruption of—their usual activities and relationships with the water resources. The developers might have used their engagement in cultural heritage projects as way to promote their businesses or to simply comply with the dominating discourse (as described above) that puts heavy weight on the issues of national identity connected with cultural heritage. Whatever their reason, it was made clear to the heritage operators in the country that the society was ready to embrace the concept of “mitigation” and that the mitigation should be flexible, reasonable, and based on clear definitions of values and impacts to these values.

Creative mitigation based on these principles could multiply chances of success. The concept of corporate social responsibility is very recent among the Albanian business community. It has been introduced mainly by large foreign corporations and projects promoted by major international funding agencies. It is, however, finding its way to becoming common practice for at least some of the local businesses, thereby creating the right context for analysis of the kind that Starr (Reference Starr2013) offers with regard to CSR and heritage conservation, sustainable development, and corporate reputation.

DISCUSSION

Albanian society is in the process of a rather long transition period from a former autocratic sociopolitical system to a liberal democracy, facing difficult issues such as economic restructuring, the adoption of a comprehensive legal and juridical system, and the widespread corruption of state officials as perceived by a large part of the population (Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe 2019). This transformation has had a strong impact on both the heritage system and the way heritage issues have entered public discourse. The heritage legal framework has changed and improved frequently in the last three decades. Consequently, the heritage system has followed that trend. Heritage education, management, and practices have also been under the pressure of the changing wider context. Traditional approaches to heritage management, particularly those embedded in a historically particular sociopolitical system, have proven to be very resistant. Most of these traditional practices of conservation, presentation, or management were successful during the second half of the twentieth century but are no longer compatible with contemporary Albanian society.

Nonetheless, they still exercise a strong influence on the discourse of today. The concept of mitigation represents the dialectic relationship between a traditionally rooted idea and the needs of contemporary developments. It has been subject to change through several new laws and procedures, but it remains within the boundaries of avoidance/documentation/recovery. Mitigation is not considered to be an open and participatory process, but rather the concern of a few professionals in decision-making forums. It is based not on a proper assessment of values of the heritage resource but on superficial knowledge and, sometimes, on myths associated with specific areas of the past. Although a formal decision/approval for mitigation is regulated by administrative procedures, no capacities are in place to follow the process on the ground. No provisions exist yet for the legal responsibilities of those who implement a mitigation measure. How is the quality of the approved mitigation assured? What happens when mitigation is not implemented at all? Although the current legislation is rigid about what can and cannot be done with sites and monuments, it remains flawed regarding many aspects of the mitigation process. Everyday practice, however, is constantly bringing forth these shortcomings and inconsistencies. As indicated in the cases described here, the need to find alternative and creative mitigations is becoming evident. The weaknesses of the system are being identified and listed for potential inclusion in the upcoming amendments to the law. They are transformed into lessons learned for the future implementation of “creative mitigation,” which is just emerging in the heritage practices in Albania and which has a long and difficult path to its consolidation and maturity.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank Gerry Wait, of the journal's editorial board, for inviting me to participate in this volume. His thoughtful comments on an earlier version of this article, together with the critical comments of the peer reviewers, helped substantially with the current presentation of the article's arguments. Thanks go also to several individuals within Trans Adriatic Pipeline management who allowed me to use not only some of the information collected during the implementation of the project but also figures 2–6.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are partly available in Agjencia e Shërbimit Arkeologjik's website at http://www.asha.gov.al/ and partly available from the author with permission from Trans Adriatic Pipeline.