In the first years after the formalization of preservation practices with the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) in 1966 (National Park Service 2018), mitigation for adverse effects to historic properties was limited. When federal undertakings harmed or destroyed significant historic properties, there were only two mitigation alternatives: data recovery for archaeology (what Lynne Sebastian in this special issue has playfully called the 3 Ds—dig, document, and destroy) and Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) and Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) documentation for architectural history. By extracting and archiving historical information before destruction, the preservation goal was to recover and collect some fraction of a historic resource's societal value—its ability to help address important questions of history, science, engineering, and art.

Importantly, however, the NHPA recognized that some federal undertakings could harm historic properties without physically altering them. For example, when federal agencies transfer real property that contains historic resources out of federal ownership, the resources lose protection under federal preservation laws. Unless adequate and legally enforceable restrictions are created as conditions of the transfer, the transfer or sale of a historic property is considered an adverse effect as per 36 C.F.R. § 800.5(a)(2)(vii) (ACHP 2004).

Such scenarios can present a quandary. If, despite a loss of federal protection, the federal agency and consulting parties desire preservation of a resource in place, or if data recovery efforts are deemed inadequate or impractical, federal agencies must find ways to mitigate an adverse effect at some conceptual and/or physical distance from the affected resource. This article explores one such creative or alternative mitigation strategy: the creation of digital information systems to (1) collect, store, and convey cultural resource information and (2) facilitate coordination between government agencies, tribes, and other parties consulting on federal undertakings.

The accumulated products of document-and-destroy mitigation efforts have piled up. Vast volumes of paper maps, forms, and reports kept at state agencies and offices never find their way into publications accessible through public and university library systems or databases. Retrieving these records from the stacks, boxes, and cabinets of State Historic Preservation Offices and other information centers requires considerable time, money, and experience. The distance to such offices often creates a hurdle too difficult to overcome, and in response, cultural resource management consultants and researchers in university settings routinely keep their own smaller libraries and make do with out-of-date and often incomplete information.

In Washington State, particularly after 1999, the Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation (DAHP) started grappling with the reality that few people visited the agency to look at HABS/HAER documents, yet archaeological consultants came in droves to search the paper files and maps for cultural resource information needed to comply with federal laws. This became particularly overwhelming in the early 2000s, when the cellular industry went on a spree of cell tower construction. In 2001, agency staff also realized that the paper trove of “gray literature” was at risk after a major earthquake struck the region (Historylink 2001), centered just a few miles from DAHP's office. At the same time, the evolution of information technologies and approaches to communication offered new ways to collect, preserve, protect, and share important cultural and historic information.

With these problems and opportunities in mind, DAHP started looking for ways to make its archives of cultural resource information more useful and secure. In the mid-1990s, DAHP started acquiring electronic tools to create an internet-based repository that would parallel the advances in consumer-driven internet technology. The result of this effort became what DAHP calls the Washington Information System for Architectural and Archaeological Records Data (WISAARD).

A number of different commercial and nonprofit digital repositories now populate the information landscape, and it is easier than ever to find published material on any given subject. Support for digital archives by major funding institutions such as the National Science Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation (e.g., JSTOR and tDAR) shows that the creation and maintenance of such tools is a valuable area of research and development for scholars, in general, and archaeologists, in particular. The reach of these tools, however, does not extend far into the vast archives held by government agencies, and the sea of gray literature remains difficult to navigate.

Today, the WISAARD provides access to digital copies of documents and datasets held by DAHP, and it creates a virtual environment for information exchange and data management among consulting parties participating in federal and state regulatory processes. In many ways, the WISAARD has changed archaeological practice and cultural resource management in Washington State for the better. We assert that developing such systems should be a priority for government agencies and other organizations that collect and manage archaeological and cultural resource information.

There are many possible ways to go about funding and building such systems, and organizations with different assets and limitations will benefit from different opportunities and approaches. In this article, we present the WISAARD as a case study and provide an outline of the system's history and function. Unlike other systems underwritten by subscription fees or large grants, the development of the WISAARD was funded through a mixture of state appropriations in DAHP's budget and money provided by state and federal agencies as mitigation for adverse effects to historic properties. We finish by considering a recent undertaking in Washington State, in which the Department of Energy provided funding for the WISAARD as creative mitigation for a transfer of property out of federal ownership, and we show how this action specifically meets the criteria for appropriate mitigation described by the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP). Because of their far-reaching benefits for research (in general) and management of cultural resources (in particular), we argue that creating, implementing, and enhancing digital information systems should be considered as a mitigation measure in addition to—or as an alternative for—traditional document-and-destroy approaches when off-site or when creative mitigation is needed to resolve adverse effects on federal Section 106 undertakings.

WHAT THE WISAARD IS AND DOES

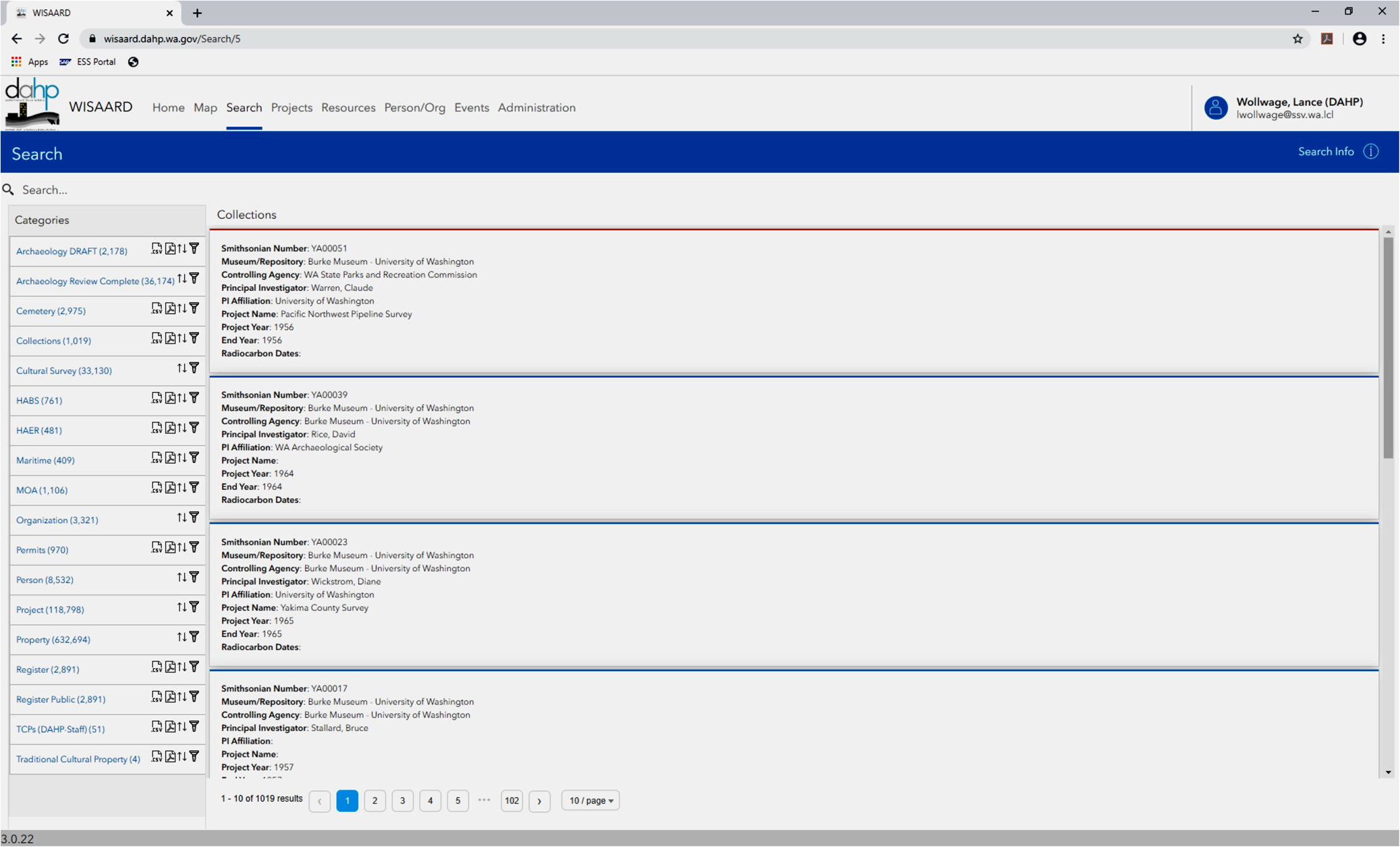

The WISAARD is Washington State's internet-accessible repository for architectural and archaeological resources and reports. Its main functions are a searchable database—both topically and geographically—data entry, and workflow organization. The WISAARD has one interface but presents users with different information depending on their point of access or permissions granted by DAHP. The public at large has limited permission to access information from DAHP's inventory of completed projects, buildings, structures, objects, maritime resources, historic districts, and sites, including those listed on the Heritage Barn Register (DAHP 2020a), Washington Heritage Register (DAHP 2020b), and the National Register of Historic Places (DAHP 2020c). The public entrance also provides access to an archaeological probability map generated with DAHP's predictive model (GeoEngineers 2009). A second level of permission allows authorized users to view the publically available data and initiate projects and submit historic inventory information, documents, and images for buildings, structures, and objects. A third level of permission provides cultural resource professionals, tribes, and public land managers access to protected archaeological site records, survey reports, cemetery information, and some information on traditional cultural places—as well as information on past and present projects under review by the agency, memoranda of agreements, programmatic agreements, state archaeological excavation permits, and archaeological collections curated with the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture at the University of Washington (Burke Museum 2020; see Figures 1 and 2). The fourth level of permission grants DAHP staff full access to all information and administrative functions. For more information and tutorials about the WISAARD, see https://dahp.wa.gov/wisaard (DAHP 2020d).

FIGURE 1. Screenshot of secure WISAARD map interface showing cultural resource survey points, lines, and polygons.

FIGURE 2. Screenshot of secure WISAARD search interface showing collections category.

HISTORY OF THE WISAARD

The WISAARD was not created whole, and we present the following evolutionary history as an example for those interested in developing systems with similar materials, needs, and wants. It began with tools DAHP already possessed—Microsoft Excel (MS Excel) spreadsheets and a few simple Microsoft Access (MS Access) databases—and grew stepwise as different needs emerged and funding became available. Individually, each step advanced a specific goal or fixed a problem. It is not finished, and the work continues. The developmental history that follows contains many technical details. For a graphic overview of the WISAARD's developmental trajectory, please refer to Figure 3.

FIGURE 3. Evolution of DAHP's digital information system technology, showing milestones along the road to WISAARD from 1999 to 2019.

The first and most time-consuming step (Phase 1) was converting paper documents to digital images. Tired of searching manually though boxes of paper reports and filings organized by county for every project review and correlating them to hand-drawn site locations on large paper USGS 7.5-minute quadrangle maps, the state historic preservation officer (SHPO) simply wanted to retrieve files at the speed of computers. The agency took time at this stage to define a vision, outline a general approach, identify logical steps, and prioritize them based on needs and cost. That initial effort took just a few days, and the vision is revisited annually.

DAHP began by investing in a document-scanning technology (i.e., Report Xtender produced by OTG Software Inc.) that created multipage tagged image files (TIFFs) stored in an SQL Server database. For over a decade, as time allowed, staff at DAHP fed documents to the scanner. In 1997, DAHP purchased commercial geographic information system (GIS) technology and started digitizing archaeological site information (with Smithsonian trinomial numbers as the key attribute) and cultural resource survey boundaries (with the National Archaeological Database, or NADB, number as the key attribute; National Park Service 2020).

In 2001, DAHP hired consultants to improve the existing MS Access databases, begin migrating MS Excel spreadsheets, and build new databases to manage the agency's different datasets and information needs. The agency initially used MS Access because it was inexpensive and easy to develop, and it fit within the state's existing technology framework. The first databases were simple. An administrative database (AdminDB) tracked agency review and consultation activity and documents, and it generated statistics for annual reports to the National Park Service and the state legislature. A survey report database (SurveyDB) stored bibliographic information about cultural resource reports and other related documents. Over the next few years, other databases were fashioned to manage archaeological site information, historic property inventories (HPI), National Register properties, state archaeological excavation permits, human skeletal remains cases, cemetery records, memoranda of agreement (MOAs), as well as HABS and HAER databases.

The databases quickly evolved, with the AdminDB becoming DAHP's centerpiece data management tool. Every project gained a digital “log” that tracked all review and compliance actions and correspondence (Figure 4). The database application generated letters that communicated DAHP's concurrence (or lack thereof) with determinations such as “No Historic Properties” or “Adverse Effect.” The letters were stored automatically in a highly structured file directory schema on DAHP's shared network drive (which made it easy to find documents), and the MS Access application contained a direct link to the file structure for convenience and streamlining. Linkages with the other databases allowed staff to quickly connect archaeological sites or historic property inventories to particular projects and review activities.

FIGURE 4. Screenshot of administrative database (AdminDB) interface and linked directory folder revealed through browser window.

Between 2002 and 2005, direct links were established between the GIS, the document file structure, and MS Access databases, which pulled together the first comprehensive “system.” Researchers coming to DAHP could sit at a computer and quickly find critical information, instead of searching through indexes and cabinets. Within this timeframe, DAHP also launched its first small MapOptix-driven web application solely for the display of the Washington Heritage Register and the National Register of Historic Places GIS data. This application moved to an Esri product platform that leveraged ArcIMS. At the time, DAHP decided to share only the register information on the site because it was the only resource type that did not have any special use constraints, unlike archaeological site information protected by Washington State's public records laws (Washington State Legislature 2006).

MOVING THE WISAARD TO THE WEB

For researchers, consultants, and DAHP staff, using the computer system was a major improvement, but consultants still needed to get to DAHP's office to access the records, sometimes at great cost to their clients and organizations. Eliminating this need and reaching a broader audience were goals identified early in the planning process, and once the fundamental pieces of the system were in place, the agency focused on making more of the system available through the World Wide Web.

As with the proceeding phase, where the biggest issue was converting paper documents to digital files, transforming DAHP's local electronic information system into an internet-accessible application (Phase 2) proved challenging because it again required migrating the data from one format to another. Most MS Access data moved to an Enterprise SQL Server, although MS Access still provided the front-end application for maintaining the data, whereas GIS data were stored on an ArcSDE geodatabase within an on-premise Enterprise ArcGIS Server. The next iteration of the WISAARD application was developed using ASP Microsoft .NET Framework 3.5, ArcGIS Server JavaScript API 1.3, ArcGIS Server 9.3, Microsoft ReportViewer, Microsoft SQL 2005, and Microsoft Internet Information Services, and it was housed behind the State's SecureAccess Washington firewall (WaTech 2020). This simple server placement meant that DAHP could start sharing other types of cultural resource information, such as archaeology, cemetery, and survey reports, that were previously exempt from public disclosure.

The document management system required some additional automation and Aquaforest imaging conversion software that converted the proprietary TIFF files (i.e., BIN) of the first document scanning software into PDF files that would make the files more widely accessible to the public. Making these changes took two years, and in 2007, DAHP released the third version of the web-based WISAARD system.

In 2009, the WISAARD expanded to include an Historic Property Inventory application, and the access roles increased from two (“public,” which received only the HPI and Register information, and “Secure,” which was able to see all available data) to three, with the creation of an “HPI – Editor” role. This function allowed users to create and manage attribute and spatial data about historic buildings, structures, and objects entirely through a web interface, and it enabled users to link back to the previous WISAARD iteration in order to retrieve the other available resource information. The ArcGIS server played a crucial role for users to add and manage spatial content, and the MS Access version of HPI was retired.

Successes of these versions of the WISAARD and WISAARD-HPI led to a substantial upgrade. Phase 3 of the WISAARD began in 2014, with the objectives of creating a single centralized application for all of DAHP's business processes and data management while upgrading DAHP's aging document management system and allowing the implementation of more specific user roles (see Table 1).

Table 1. WISAARD Phase 3 permission categories.

One lesson from the first two development phases was a need for greater flexibility—the ability to adapt the system to new data, rules, policies, or laws. Until then, small changes could require significant programming work. Consequently, a primary goal for Phase 3 was for DAHP staff to have the ability to reconfigure the system when needed. DAHP obtained a scalable, “normalized” SQL Server database structure so that staff could alter map services at will without any programming. Phase 3 also introduced a web-based project management framework as well as the ability to submit Section 106 and other review documents online.

The sixth version of the WISAARD focused on creating a user interface similar to the historic property online form, where users could upload their archaeological photos, sketch maps, site observations, and artifact descriptions, as well as map the site directly into the system's ArcSDE geodatabase. This addition made the data live—WISAARD users are able to see current site conditions and updates as they are being reported to DAHP.

For the seventh WISAARD iteration, which was released in 2017, DAHP extended real-time accessibility to some review and compliance components, and it made consulting with DAHP on project areas and Areas of Potential Effect (APEs) much faster and easier. Where DAHP once received, mailed, and e-mailed project descriptions and maps, the WISAARD enabled users to identify all of their consultation participants (tribes, state, federal, local governments, and consulting cultural resource professionals), draw the project APE directly into the application, upload schematic documents and photos, and send and receive comments from project contacts. Today, authorized users may submit cultural survey documents, upload/incorporate spatial data, and create full archaeological inventories, including photos and other attachments, along with their project areas and formal consultation letters. This type of interaction between agency stakeholders and DAHP has revolutionized how DAHP manages information, and it has greatly reduced the time it takes to turn around project reviews.

The eighth version of the WISAARD, just released, attempts to clean up the user experience and provide a cheaper and more efficient data-sharing platform. DAHP's data sharing program (DAHP 2020e) will become fully integrated into the WISAARD's ArcGIS Portal for Server, and data-sharing partners will be able to incorporate DAHP's geospatial data straight into their own web-based applications specific to their regulatory oversight, disaster management programs, and land management needs.

CHALLENGES ALONG THE WAY TO THE WISAARD AND A FEW LESSONS LEARNED

DAHP staff and contractors tasked with WISAARD development overcame many obstacles to create the system that exists today. The most time-consuming aspect of the project is also the most fundamental. As mentioned above, the transfer of legacy papers to digital files in a searchable geographic information system consumed over a decade, with several full-time employees committed to the cause. Much of this time was spent on quality control. Many older documents did not meet current reporting standards and could not be placed on a map with confidence. Washington State law RCW.27.53.060 protects archaeological sites on both public and private land, so incorrectly mapped or overly broad site boundaries have legal implications for landowners (Washington State Legislature 2002).

Even today, the quality of reports uploaded to the WISAARD is as variable as the people who produce them, and quality control remains an ongoing priority. Beyond relying on DAHP staff who review documents during Section 106 and other regulatory review processes, some of the WISAARD's design elements aim to control variability by forcing submitters to provide specific information with dropdown menus and required data entry fields. Nonetheless, up to 10% of the reports submitted to DAHP in recent years remain unmappable but contain other information that archaeologists need. Such reports are still added to the WISAARD and may be found through the system's search function, but they do not appear on the map. For these issues, we have yet to discover an adequate technological solution, although the current efforts focus on making the system more user-friendly.

In terms of archaeological site and historic-building inventory data, the WISAARD's reliability depends on some level of quality control. Crowd-sourced data can vary widely in terms of quality. Users come and go, and no number of pull-down menus, checkboxes, or required fields can completely control for the variability of the people who are producing the data that populate the system. Simply making sure that the inventoried sites are mapped in the correct location is something that requires checking given the limitations of address locators.

All of this data wrangling led to further realizations. The first is that it is best to segment the work of creating a digital information system by dataset and to complete the work of digitizing the data and building an interface before beginning another. We recommend starting small and easy, with the most important or most manageable data sets. Done this way, each step clearly advances toward the goal of a comprehensive system and gives developers and staff the experience to tackle larger and more difficult data sets later.

Lastly, we would stress that as one builds the technology (e.g., data structures and interfaces), one must also invest in the development of training materials. The technology skill level of our users ranges from beginner to advanced, and the goal continues to be to make the system as intuitive as possible. It is impossible, however, to design for every situation, and this is where training is necessary—either in the form of online tutorials or in-person teaching. User expectations will be high, and training and tutorials will help alleviate frustration. But, be mindful that creating comprehensive training manuals may not be possible if you are building in pieces, or if you do not have the budget or staff time to devote to their production. If that is the case, it is essential to have staff customer support available via email or phone. The WISAARD is not just a data repository. It also contains workflow tools for a regulatory process that is anything but regular. Some interpretation of what to put where and when is necessary in order to get the information in the correct location at the correct time and directed to the correct person.

The WISAARD we have presented here was 20 years in the making, and it has some quirks. We expect that its evolution will continue forever as we iron out the wrinkles each new development creates and try to stay abreast of new technologies.

DIGITAL INFORMATION SYSTEMS AS ALTERNATIVE MITIGATION

Access to accurate and timely information is a fundamental concern in any research endeavor, and systems such as the WISAARD provide large benefits for researchers in academic settings and cultural resource consultants alike. Aside from the advantages of having easy access to up-to-date information, researchers profit directly by avoiding the costs of traveling to the agency. A year after the WISAARD launched on the web in 2009, DAHP staff calculated that 200 professionals who signed up to use the secure web portal collectively saved 671 hours and almost 2,000 gallons of gasoline by not commuting from their various offices to the agency (Strader et al. Reference Strader, Kramer, Duvall and Brooks2009). They also saved 165,000 sheets of paper by downloading electronic files instead of photocopying cultural resource reports. Since then, the WISAARD's professional user base has expanded to over 1,800 individuals.

For those involved in cultural resource management and consultation under Section 106 of the NHPA, the WISAARD provides quick, secure access to information needed to review and consult on federal undertakings. With the ability to control the kinds of information and documents that different user types see, DAHP can now give everyone the most current data available needed to make informed decisions in real time while safeguarding sensitive information by providing protected documents on a need-to-know basis. This level of accessibility has fostered efficient interaction between DAHP staff, federal agencies, and tribal partners, and it has greatly reduced the time it takes to turn around project reviews. The average time for DAHP to respond to requests, queries, and determinations under Section 106 has decreased to three days.

Perhaps most importantly, the WISAARD has allowed DAHP to expand access to cultural resource information to both the public at large and to public planners and land-managers at the state and local level. Use of the WISAARD and its contents is free to anyone with a computer and internet connection. Map functionality and geographic search capability also make the system more approachable and help expand accessibility to people without backgrounds in archaeological or historical research. Instead of searching by esoteric keywords or names, laypersons can quickly identify and view records and reports for an area of interest by circling it on map.

Building these systems is costly, however. The WISAARD is a multimillion-dollar system, paid for in pieces as funding became available from multiple sources and agencies. Although DAHP has long sought funds through the state legislature as part of the agency's biannual budgeting process, many of the components of the WISAARD were funded by agencies that stood to benefit from the development of the system. For example, the Washington State Public Works Board found seed money for DAHP's predictive model in a limited region of the state. Grant County Public Works, which manages large areas with large numbers of sites along the Columbia River, funded further development of the model, which also advanced DAHP's GIS capabilities in general. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and the Washington State Department of Transportation paid for a pilot program that put National Register documents on the web, which allowed DAHP to begin building its website architecture.

More recently, when the Department of Energy (DOE) transferred land out of federal ownership on the Hanford Nuclear Reservation, it needed to mitigate for the loss of protection that federal ownership provides for cultural resources, even though no historic properties faced immediate or direct threats. However, large numbers of archaeological site records needed updating before the sites left federal control. To resolve the adverse effect, the DOE, DAHP, and consulting tribes—in consultation with the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP 2020a)—developed a memorandum of agreement that stipulated and provided funds for the development of DAHP's online system for archaeological site and traditional cultural property form submissions.

For those concerned that supporting such mitigation measures could lead to “checkbook mitigation,” the ACHP formalized its thoughts on the matter in a letter to the president of the National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers (NCSHPO; see Figure 5 for letter in full). In it, Mr. John Fowler of the ACHP lists the benefits of electronic cultural resource information systems we described above, stating that in addition to simply making vital information available to federal agencies during Section 106 reviews, the development of such tools “increase the efficiency and effectiveness of information exchange between federal agencies, SHPOs, and others.” The letter also explains how funding for electronic information systems should be appropriate for mitigation “for most, if not all, adverse effects so long as the database contains some of the types of historic properties affected by the particular undertaking” (J.M. Fowler to E. Hughes, letter, 10 March 2017).

FIGURE 5. Letter from Mr. John Fowler, Executive Director, Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, to Ms. Elizabeth Hughes, President, National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers.

Other ACHP guidance (ACHP 2020b) on appropriate options to resolve adverse effects lists four key considerations:

• What is in the public interest?

• What are the benefits to, or concerns of, the consulting parties, those they represent, and those who ascribe importance and value to the property?

• If the proposed mitigation is designed to advance our knowledge about the past, how will this knowledge be provided to the public, to schools, to tribes or NHOs, and to professional archaeologists?

• Will it enhance the preservation and management of listed or eligible archaeological sites in a region?

Mr. Fowler's letter further adds:

In order to be appropriate, the negotiated and agreed-to mitigation measures should bear a reasonable relationship to the undertaking's adverse effects or, more generally, the types of adverse effects or types of historic properties at issue. Funding to support cultural resource electronic information systems should therefore be appropriate mitigation for most, if not all, adverse effects so long as its database contains some of the types of historic properties affected by the particular undertaking. So, for example, such mitigation would be appropriate for an undertaking that may affect a particular archaeological site in Washington State if similar archaeological sites in Washington State are part of the system's database. There is a reasonable likelihood that such a well-supported system would better ensure consideration of such types in the future [Fowler to Hughes, 2017].

As mitigation for the adverse effect of the DOE relinquishing land with numerous cultural resources and the subsequent loss of federal protection, the MOA provision that funded WISAARD development meets all of the considerations above. The WISAARD increases the availability of cultural resource information for all parties participating in cultural resources review and consultation, as well as the public at large. The ready availability of up-to-date information decreases the work needed to review and consult on Section 106 undertakings, and it greatly reduces the time needed to identify and evaluate historic properties, determine effects, and receive concurrence from consulting parties. The specific WISAARD improvement to be funded by DOE—an interface for online archaeological site form submissions—directly related to and aimed to improve DOE's ability to submit hundreds of site forms for the resources being adversely affected.

CONCLUSION

For historic property types such as archaeological sites and historic buildings, data recovery is often the main part of mitigation plans offered by federal agencies with undertakings that will destroy part or all of a historic property. In theory, by extracting important information before destruction, we recover some part of a historic resource's cultural value. For all of the twentieth century (and much of the twenty-first), the deliverable product of such mitigation efforts consisted of paper forms and reports kept by SHPOs and HABS/HAER records filed with the Library of Congress. Identifying and accessing these records from the stacks, shelves, and filing cabinets of SHPO offices and information centers requires considerable time and expense, even for experienced professionals.

Improvements in technology and approaches to communication over the last 20 years or so have led to many new ways to collect, preserve, protect, and share important cultural and historic information. Web-based GIS systems such as the Washington Information System for Architectural and Archaeological Records Data take advantage of the technologies and information-gathering habits of modern life, and they increase access to cultural resource information in ways that directly benefit the public, Native American tribes, and scientific communities. The benefits such systems provide makes funding them a useful option for federal agencies with undertakings where data recovery is impossible or undesirable, and where resolving adverse effects to historic properties requires off-site or creative mitigation efforts.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John Douglass and Shelby Manning for inviting us to participate in a session on creative mitigation at the 2019 Society for American Archaeology conference, and for pursuing this opportunity to publish our work in Advances in Archaeological Practice (AAP). We also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful and constructive comments and suggestions.

Data Availability Statement

All data provided in this article are available from the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation through the provided links or by contacting the agency.