Summations

-

• Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (i.e., exenatide, liraglutide, and semaglutide) result in attenuation of alcohol-related behaviours, including alcohol consumption, alcohol preference, and alcohol-induced neurochemical responses in animal models.

-

• Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists vary with specific brain regions targeting in animal models, with observed effectiveness in the NAc and VTA implicated in alcohol use disorder.

-

• Results on whether glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists are able to reduce compulsive drinking behaviour in individual’s living with alcohol use disorder are mixed, and there remains a need for adequate and well studies.

Considerations

-

• There are limited clinical studies assessed within this review, with contrasting findings on the efficacy of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on alcohol usage.

-

• The transient nature of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists were not assessed in the literature reviewed in this paper. Notably, receptor desensitisation and neuroadaptations may limit the efficacy of the analogues.

-

• Although treatment combinations have been suggested to yield greater efficacy, the reviewed literature did not examine the synergistic effects of varied glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on alcohol-related behaviours.

Introduction

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) has been widely used to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2 DM), with extant literature supporting its role in glycemic and appetite control (Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, Lund, Knop and Vilsbøll2018). This peptide consists of 30 amino acids and is synthesised in the endocrine epithelial L cells, pancreatic alpha cells, and by a subset of neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) in the brainstem (Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, Lund, Knop and Vilsbøll2018; Holst, Reference Holst2024; Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Zong, Ma, Tian, Pang, Zhang and Gao2024). Stimulated by ingested macronutrients, GLP-1 is secreted postprandial in response to an oral glucose load (Holst, Reference Holst2024). Enteroendocrine L cells, responsible for secreting GLP-1, are distributed throughout the gastrointestinal tract, with proximal L cells playing a crucial role in elevating GLP-1 levels in plasma (Holst, Reference Holst2024; Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Zong, Ma, Tian, Pang, Zhang and Gao2024).

GLP-1 has only one known receptor, GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R), which is widely expressed throughout the body, including the digestive system, cardiovascular system, central nervous system (CNS), and peripheral nervous system (Holst, Reference Holst2024; Au et al., Reference Au, Zheng, Le, Wong, Phan, Teopiz, Kwan, Rhee, Rosenblat, Ho and McIntyre2024). Notably, GLP-1Rs in circumventricular organs are targets for peripheral GLP-1, particularly after large meals or under conditions like rapid gastric emptying (Holst, Reference Holst2024). Within the CNS, these receptors are predominantly expressed in brain regions involved in processing rewards, including the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and nucleus accumbens (NAc) (Marty et al., Reference Marty, Farokhnia, Munier, Mulpuri, Leggio and Spigelman2020). Recent literature demonstrated a link between GLP-1R signalling and dopamine (DA) mechanisms within brain regions involved in substance usage and addiction (Jensen et al., Reference Jensen, Galli, Thomsen, Jensen, Thomsen, Klausen, Vilsbøll, Christensen, Holst, Owens, Robertson, Daws, Zanella, Gether, Knudsen and Fink-Jensen2020; Au et al., Reference Au, Zheng, Le, Wong, Phan, Teopiz, Kwan, Rhee, Rosenblat, Ho and McIntyre2024). Particularly, GLP-1R activation and DA regulation may underlie GLP-1R’s effects on reward, provided dopamine transporter’s (DAT) role in regulating DA neurotransmission. As these regions are implicated in understanding addiction and substance use, as they regulate rewarding effects of substance use, GLP-1Rs may have implications for modulating behaviours associated with appetite and alcohol consumption (Marty et al., Reference Marty, Farokhnia, Munier, Mulpuri, Leggio and Spigelman2020; Badulescu et al., Reference Badulescu, Tabassum, Le, Wong, Phan, Gill, Llach, McIntyre, Rosenblat and Mansur2024).

As an agonist to GLP-1 (GLP-1RAs), GLP-1RAs can serve as a mediator of aforementioned reward and appetite associated signalling. GLP-1RAs, including semaglutide, liraglutide, tirzepatide, and exenatide, are drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of obesity and T2 DM (Thomsen et al., Reference Thomsen, Holst, Molander, Linnet, Ptito and Fink-Jensen2018; Holst, Reference Holst2024). Regarding its underlying mechanisms, these agonists activate GLP-1R, mimicking the effects of endogenous GLP-1, and resulting in enhanced insulin secretion, attenuated glucagon release, reduced gastric emptying rate, and suppressed central appetite (Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Zong, Ma, Tian, Pang, Zhang and Gao2024). Similarly to GLP-1 and its analogues, GLP-1RAs can modulate food intake and hedonic eating by targeting neural substrates, particularly within the mesolimbic reward pathways (e.g., VTA and NAc), altering satiety and reward responses to salient substances often subjected to abuse (Eren-Yazicioglu et al., Reference Eren-Yazicioglu, Yigit, Dogruoz and Yapici-Eser2021; Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Zong, Ma, Tian, Pang, Zhang and Gao2024). GLP-1RAs have further been demonstrated to regulate DA signalling through a process tightly controlled by the DAT, implicating its role in regulating the reward pathway (Jensen et al., Reference Jensen, Galli, Thomsen, Jensen, Thomsen, Klausen, Vilsbøll, Christensen, Holst, Owens, Robertson, Daws, Zanella, Gether, Knudsen and Fink-Jensen2020). Notwithstanding, GLP-1RAs effects on substance-related reward behaviours and GLP-1RAs’ potential to modulate alcohol consumption remains underexplored. The mesolimbic pathways targeted by GLP-1RAs play an integral role in the rewarding effects of alcohol consumption, influencing alcohol seeking motivation and reinforcement. By modulating these pathways, GLP-1RAs serve as a potential therapeutic mechanism to reduce alcohol intake via alteration of reward process pathways. Despite this, the role of GLP-1RAs in alcohol use disorder (AUD) remains largely underexplored, despite their established efficacy in managing metabolic disorders. Alcohol consumption is widespread globally, and its potential benefits and risks have sparked considerable debate among researchers. It is associated with all-cause, cardiovascular disease, and cancer mortality, among other conditions (Tian et al., Reference Tian, Liu, Zhao, Jiang, Liu, Zhao and Wang2023). AUD is a chronic, relapsing condition marked by an irresponsible compulsion to habitually seek alcohol, inability to control alcohol intake, and the development of a negative emotional states leading to dependence on alcohol and associated adverse health concerns (Marty et al., Reference Marty, Farokhnia, Munier, Mulpuri, Leggio and Spigelman2020). Alcohol’s debilitating effects can further extend to unintentional injury and suicide, contributing to pressing consequences for the engaged individual, relatives, and society at large (Klausen et al., Reference Klausen, Jensen, Møller, Le Dous, Jensen, Zeeman, Johannsen, Lee, Thomsen, Macoveanu, Fisher, Gillum, Jørgensen, Bergmann, Enghusen Poulsen, Becker, Holst, Benveniste, Volkow and Fink-Jensen2022). Although the FDA has approved several agents for the treatment of AUD – including disulfiram, naltrexone, and acamprosate – many individuals do not adequately benefit from these treatments (Litten et al., Reference Litten, Wilford, Falk, Ryan and Fertig2016). With AUD remaining a global leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality, understanding GLP-1 RA’s potential in regulating alcohol consumption could open new avenues for therapeutic approaches. As such, this review strives to investigate this potential therapeutic avenue, addressing the significant gap in the development of effective treatment strategies for AUD. Assessment of literature aims to provide an overview of current trends in GLP-1RAs administration in modulation of AUD and related behaviour.

Methods

Search strategy

This systematic review was conducted in adherence to the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (Page et al., Reference Page, Moher, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, McDonald and McGuinness2021). Relevant literature was extracted from the following databases: Web of Science, OVID (MedLINE, Embase, AMED, PsychInfo, JBI EBP), and PubMed were used to systematically search for relevant articles from database inception to October 27th, 2024. The search queries used for this review is of the following: (‘GLP-1’ OR ‘Glucagon-Like Peptide-1’ OR ‘Glucagon-Like Peptide 1’ OR ‘GLP-1 Agonist’ OR ‘Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Agonist’ OR ‘Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Agonist’ OR ‘Semaglutide’ OR ‘Dulaglutide’ OR ‘Trulicity’ OR ‘Exenatide’ OR ‘Liraglutide’ OR ‘Lixisenatide’ OR ‘Tirzepatide’) AND (‘Alcohol’ OR ‘Alcohol use disorder’ OR ‘AUD’ OR ‘Alcoholism’ OR ‘Ethanol Administration’ OR ‘Ethanol’).

Study selection and inclusion criteria

Articles obtained from databases were screened through Covidence, wherein duplicated articles were automatically excluded (Systematic review management, 2023). Two independent reviewers (H.A. and Y.J.Z.) reviewed the titles and abstracts according to the inclusion and exclusion guidelines (Table 1). Furthermore, relevant English-language primary and secondary sources were then examined through full-text screening and included for extraction if they reported on GLP-1RA-associated changes to alcohol or ethanol consumption. Discrepancies were resolved following thorough discussion between reviewers.

Table 1. Eligibility criteria

Data extraction

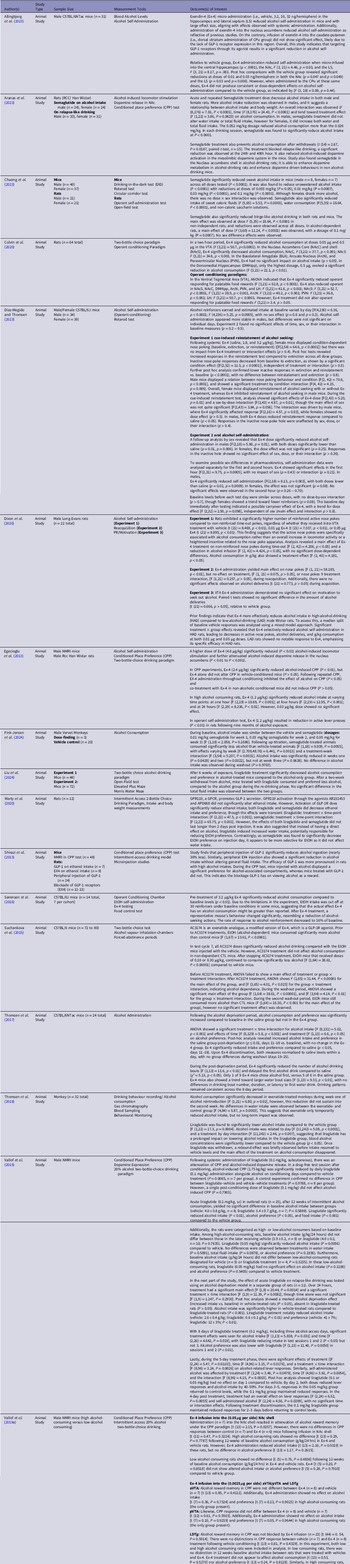

Literature applicable to alcohol-associated behaviours and GLP-1RA administration were obtained and further organised following the piloted data extraction guidelines (Table 2). Extracted data was established a priori, involving (1) author(s), (2) study design, (3) Sample Size, (4) measurement tools, and (5) outcome of interest(s) for preclinical studies (Table 2). An additional category, diagnosis, was included for clinical studies (Table 3). Two reviewers (C.S. and Y.J.Z.) extracted data from relevant literature, followed up with thorough discussion to resolve potential conflicts. Alcohol consumption and outcome of interest(s) involved GLP-1 or GLP-1RA administration in the context of alcohol-related behaviours in preclinical and clinical literature.

Table 2. Characteristics of preclinical animal studies examining association between GLP-1 and alcohol-related behaviour

Table 3. Characteristics of clinical studies examining association between glucagon-like peptide-1 and alcohol-related behaviours

Quality assessments

Quality assessment of pre-clinical studies was conducted using SYRCLE’s risk of bias analysis tool for animal studies, whereas quality assessment of clinical studies was conducted using Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies of the National Institute of Health (Hooijmans et al., Reference Hooijmans, Rovers, de Vries, Leenaars, Ritskes-Hoitinga and Langendam2014; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Wang, Yang, Huang, Weng and Zeng2020; National Institute of Health, 2013). Similarly, quality assessment of cohort studies was conducted using the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Wang, Yang, Huang, Weng and Zeng2020; National Institute of Health, 2013). Independent reviewers (H.A., C.S., and Y.J.Z.) examined literature risk of bias and resolved all conflicts through further discussions. These tools were chosen for their established validity and reliability in assessing risk of bias in animal, clinical, and observational studies. The inclusion and exclusion criteria, comprehensive overview of data, and methodological quality are organised as supplementary materials (Table S1, S2).

Results

Search results

A systematic search of relevant literature yielded 1,309 studies. Among these, 31 duplicates were identified manually, and 590 were identified by Covidence (Fig. 1). 688 studies were screened based on their titles and abstracts according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). Following this, 28 full-text studies were assessed, with 21 studies deemed relevant and included for data extraction (Table 2). 6 studies were excluded, consisting of studies with incorrect study designs (n = 4), without available full text (n = 1), and with wrong outcomes (n = 1). Ultimately, 21 studies meeting the eligibility criteria were included in this systematic review (Table 2).

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram of literature searches relevant to glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and alcohol consumption in preclinical and clinical studies (Systematic review management, 2023).

Methodological quality

All controlled intervention studies were described as double-blinded, randomised trials, and had sufficient sample size to detect a clinically significant effect. Included observational cohort studies had sufficient sample size to detect a clinically significant effect, whilst employing consistent exposure measures across all study participants. Notwithstanding, Quddos et al. (Reference Quddos, Hubshman, Tegge, Sane, Marti, Kablinger, Gatchalian, Kelly, DiFeliceantonio and Bickel2023) did not clearly specify the study population, and did not employ random assessment (Table S2). As such, we only examined the objective results investigating the association between GLP-1 RA administration and alcohol consumption behaviour for this study.

Most animal studies employed similar groups at baseline and/or adjusted for confounders and randomly housed animals during the experiment. Common limitations included the lack of blinding and random outcome assessment. Most studies did not exhibit a high degree of bias. Notwithstanding, studies rated ‘fair’ generally exhibited higher levels of categories marked as ‘Not Reported’ or ‘Not Applicable’, further omitting information regarding allocation concealment and insufficiently addressing incomplete outcome data (Table S1). Albeit the presence of limitations, the qualities of results were not affected.

GLP-1 and GLP-1RA effect on alcohol-related behaviors

Cumulatively, we identified 21 studies investigating the role of GLP-1RA on alcohol consumption or administration in preclinical (n = 19) and clinical (n = 2) studies. The GLP-1RAs identified and assessed in this review are exenatide, semaglutide, and liraglutide.

Preclinical evidence on the influence of GLP-1RA on alcohol-related behaviors

To understand the influence of GLP-1RAs (i.e., exenatide, semaglutide, and liraglutide) on alcohol consumption, 19 animal studies, consisting of rodents and monkey models, were identified. These studies used intracerebral injections to target varying brain regions, as well as peripheral infusion, to assess alcohol-associated behaviours.

The role of exenatide on alcohol-related behaviors in preclinical studies

We identified 13 studies evaluating the impact of exenatide on alcohol consumption, demonstrating that exendin-4 (Ex-4) administration attenuates alcohol-related behaviours across various brain regions (Colvin et al., Reference Colvin, Killen, Kanter, Halperin, Engel and Currie2020; Allingbjerg et al., Reference Allingbjerg, Hansen, Secher and Thomsen2023; Díaz-Megido & Thomsen, Reference Díaz-Megido and Thomsen2023; Egecioglu et al., Reference Egecioglu, Steensland, Fredriksson, Feltmann, Engel and Jerlhag2013; Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, McNally and Ong2020; Shirazi et al. Reference Shirazi, Dickson and Skibicka2013; Sørensen et al., Reference Sørensen, Caine and Thomsen2016; Suchankova et al., Reference Suchankova, Yan, Schwandt, Stangl, Caparelli, Momenan, Jerlhag, Engel, Hodgkinson, Egli, Lopez, Becker, Goldman, Heilig, Ramchandani and Leggio2015; Thomsen et al., Reference Thomsen, Dencker, Wörtwein, Weikop, Egecioglu, Jerlhag, Fink-Jensen and Molander2017; Thomsen et al., Reference Thomsen, Holst, Molander, Linnet, Ptito and Fink-Jensen2018; Vallof et al., Reference Vallöf, Kalafateli and Jerlhag2019a; Vallof et al., Reference Vallöf, Vestlund and Jerlhag2019b).

Allingbjerg et al. (Reference Allingbjerg, Hansen, Secher and Thomsen2023) administered Ex-4 at varying doses (i.e., vehicle, 3.2, 10, 32 ng/hemisphere) in the NAc, ventral hippocampus (HPC), and lateral septum (LS), resulting in attenuated alcohol self-administration in C57BL/6J mice with a substantial effect size. Specifically, when micro-infused into the ventral HPC, Ex-4 significantly decreased self-administration compared to the vehicle group (p < .0001). Similar reductions were observed following administration to the NAc, F (3, 21) = 4.46, p = 0.03, and lateral septum (LS), F (3, 21) = 8.17, p = 0.001. Post hoc analyses further supported that doses of 0.01 and 0.03 ng/hemisphere in both the NAc and LS significantly reduced alcohol self-administration compared to vehicle (NAc: p = 0.047 and p = 0.049; LS: p = 0.03 and p = 0.006). A higher dose of Ex-4 (4.8 μg/kg) significantly reduced alcohol-induced locomotor stimulation and attenuated alcohol-induced dopamine release in the NAc (P < 0.01 to P < 0.001), highlighting its impact on both behavioural and neurochemical responses to alcohol (Egecioglu et al., Reference Egecioglu, Steensland, Fredriksson, Feltmann, Engel and Jerlhag2013).

Additional findings by Colvin et al. (Reference Colvin, Killen, Kanter, Halperin, Engel and Currie2020), support that Ex-4 administration into the ventral tegmental area (VTA) significantly reduced alcohol intake at 0.05 µg and 0.5 µg (F (3,21) = 50.7, p < 0.0001), aligning with reductions observed in the NAc core and shell (NAcC: F (3,21) = 37.7, p < 0.001; NAcS: F (3,21) = 34.6, p < 0.001). In the Dorsomedial Hippocampus (DMHipp), only the highest dose of 0.5 µg produced a significant reduction in alcohol consumption F (3,21) = 22.1, p < 0.01), indicating a dose-dependent effect specific to this region.

To further support these findings, Dixon et al. (Reference Dixon, McNally and Ong2020) demonstrated that intra-VTA injections of Ex-4 (i.e., vehicle, 0.01 μg, 0.05 μg) yielded reduction in alcohol-self administration, which was most prominent in high-alcohol Long-Evans rats. It appears that Ex-4 selectively reduced alcohol-seeking behaviour in rats with a demonstrated specificity toward high-alcohol-drinking (HAD) phenotypes. In Experiment 1, Ex-4 treatment significantly attenuated non-reinforced nose pokes (F (2,42) = 4.206, p < 0.05), alcohol infusions (F (2,42) = 4.424, p < 0.05), and total alcohol consumption (F (2,40) = 4.181, p < 0.05), indicating that active nose pokes were directly associated with alcohol consumption rather than non-specific increases in activity. However, in Experiment 2, Ex-4 had no impact on reacquisition behaviours, as evidenced by unchanged alcohol deliveries (t (21) = 0.773, p > 0.05), and in Experiment 3, Ex-4 administration in the VTA showed no effect on motivation to seek alcohol (t (21) = 0.666, p > 0.05). This lack of effect on reacquisition and motivation suggests that Ex-4’s influence is not on general alcohol-seeking motivation but rather specific to conditions of established high alcohol intake.

Likewise, in high alcohol-consuming rats, 1.2 μg/kg Ex-4 effectively reduced alcohol intake across multiple time points ([1 hour: F (2,19) = 18.69, P < 0.001; 4 hours: F (2,19) = 12.95, P < 0.001; 24 hours: F (2,19) = 8.236, P < 0.01]), whereas a lower 0.03 μg/kg dose had no significant effect (Egecioglu et al., Reference Egecioglu, Steensland, Fredriksson, Feltmann, Engel and Jerlhag2013). Additionally, in an operant self-administration test, 1.2 μg/kg Ex-4 significantly reduced active lever presses (P < 0.01) in rats with prolonged alcohol exposure, indicating its potential to suppress established alcohol-seeking behaviours.

In conditioned place preference (CPP) experiments, a 2.4 μg/kg dose of Ex-4 significantly reduced alcohol-induced CPP (P < 0.01) without affecting CPP in vehicle-conditioned mice (P > 0.05), demonstrating specificity for alcohol-related cues. When administered throughout conditioning, Ex-4 inhibited alcohol’s effect on CPP (P < 0.05), and co-treatment in non-alcohol-conditioned mice did not induce CPP (P > 0.05). An increased dose (i.e., 3.2 μg/kg Ex-4) further reduced alcohol consumption relative to baseline (P < 0.01) (Sørensen et al., Reference Sørensen, Caine and Thomsen2016). Furthermore, mice response to alcohol reinforcement was reduced to 16% of the baseline, demonstrating reduction in alcohol-seeking behaviours.

Further evidence in accordance with the aforementioned findings are provided by Vallof et al. (Reference Vallöf, Kalafateli and Jerlhag2019a), wherein researchers infused Ex-4 into the NAcS in low and high alcohol consuming mice. Ex-4 infusion into the NAcS (0.05 μg per hemisphere) resulted in an attenuation of alcohol reward memory under CPP testing (t (13) = 2.15, P = 0.0257)). However, there were no distinctions in CPP responses between control and Ex-4 mice (t (11) = 0.47, P = 0.3224)). Additionally, low alcohol consuming rats showed no significant alterations (t (5) = 0.76, P = 0.4836)) following 12-weeks of baseline alcohol consumption in Ex-4 and vehicle rats (Vallof et al., Reference Vallöf, Kalafateli and Jerlhag2019a). Locomotor response to alcohol was further inhibited by nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS)-Ex-4 administration at 0.05 μg per hemisphere at one, two, and 24 hours (P < 0.001) (Vallof et al., Reference Vallöf, Vestlund and Jerlhag2019b). Alcohol response was significantly decreased in Ex-4 treated mice (P < 0.05, F (3,49) = 2.85, P = 0.0469). Consistent with existing literature, Ex-4 treated mice showed a declined presence for the alcohol-associated compartment compared to controls in CPP testing (P < 0.05) (Vallof et al., Reference Vallöf, Vestlund and Jerlhag2019b).

Alongside Ex-4’s disparate impact in varying drinking phenotypes (i.e., high versus low consumption), studies further characterised potential sex differences and alcohol-related behaviours following Ex-4 administration (Díaz-Megido & Thomsen, Reference Díaz-Megido and Thomsen2023). For cue-induced reinstatement, systemic Ex-4 treatment (saline, 1.8, and 3.2 μg/kg) had no impact on reinstatement responses in female mice, who showed condition-dependent nose poking [F (2,54) = 64.6, p < 0.0001] with a lack of treatment effect (p > 0.4) (Díaz-Megido & Thomsen, Reference Díaz-Megido and Thomsen2023). Post hoc analysis confirmed that reinstatement responses exceeded extinction, and inactive responses decreased from baseline to extinction (both p < 0.0001), with no significant differences between reinstatement and extinction (p > 0.8). In male mice, however, Ex-4 significantly reduced reinstatement behaviour, showing a dose-dependent response ([F (2,16) = 4.57, p = 0.03]).

Analysis further revealed a dose effect ([F (2,43) = 5.20, p = 0.01]) and a sex-by-dose interaction ([F (2,43) = 4.87, p = 0.01]), driven by male responses. Inactive nose-poke responses were unaffected by sex or dose (p > 0.4). Additionally, Ex-4 significantly reduced oral alcohol self-administration in males ([F (2,18) = 5.80, p = 0.01]), with both doses decreasing intake relative to saline group (p = 0.01, p = 0.006). Notwithstanding, female mice had no significant dose effect (p = 0.25). Additional analysis for the first- and second-hour following treatment indicated Ex-4 reduced male self-administration in the first hour ([F (2,18) = 8.13, p = 0.003), with both doses yielding lower alcohol-related behaviours than saline (i.e., p = 0.02, p = 0.0009). Female mice displayed a non-significant trend (p = 0.08), with no significant effects observed in the second hour (p = 0.26 − 0.70) (Díaz-Megido & Thomsen, Reference Díaz-Megido and Thomsen2023).

Correspondingly, Thomsen et al. (Reference Thomsen, Dencker, Wörtwein, Weikop, Egecioglu, Jerlhag, Fink-Jensen and Molander2017) identified a significant increase in alcohol consumption and preference compared to baseline in saline (p ≤ 0.01, days 11–18 vs. baseline) but not Ex-4 C57BL/6NTac mice groups, post-alcohol deprivation. Ex-4 significantly reduced alcohol intake and preference compared to saline (p < 0.05, days 11–18). In the post-deprivation period, Ex-4 significantly reduced the number of alcohol drinking bouts ([F (1,13) = 11.6, p < 0.01]) and delayed the first alcohol drink compared to the saline group (χ2 = 5.13, p < 0.05). Only one of nine Ex-4 mice chose alcohol first, versus five of six in the saline group. With Ex-4 discontinuation, both measures normalised to saline levels within a day, with no group differences during washout (days 19 to 25). Thomsen et al. (Reference Thomsen, Holst, Molander, Linnet, Ptito and Fink-Jensen2018) followed up their research in monkeys, wherein alcohol consumption was significantly attenuated following exenatide treatment in week one of alcohol reintroduction (F (1,21) = 6.80, p = 0.02), but this effect was not preserved in week two.

With peripheral injection of Ex-4, there was also a significant reduction in alcohol consumption, without alterations in general fluid intake (Shirazi et al., Reference Shirazi, Dickson and Skibicka2013). Similar effects were observed in a modified version of Ex-4 (i.e., AC3174), wherein AC3173 doses significantly reduced alcohol consumption relative to vehicle EtOH mice (Suchankova et al., Reference Suchankova, Yan, Schwandt, Stangl, Caparelli, Momenan, Jerlhag, Engel, Hodgkinson, Egli, Lopez, Becker, Goldman, Heilig, Ramchandani and Leggio2015). Prior to treatment, EtOH (alcohol-dependent) mice consumed significantly more alcohol than control mice (F (1,67) = 13.61, P < 0.0001). Following, AC3174 administration reduced alcohol drinking, but did not significantly affect alcohol consumption in non-alcohol-dependent control mice.

Literature further demonstrated that selective administration in brain regions is crucial for Ex-4 effectiveness, as certain brain regions may not be an optimal targeting site. Notably, Ex-4 did not yield significant effects when injected in the caudate putamen (CPu), basolateral amygdala (BLA), arcuate nucleus (ArcN), paraventricular nucleus (PVN), anterior VTA (aVTA), posterior VTA (pVTA), and lateral dorsal tegmental nucleus (LDTg) (Colvin et al., Reference Colvin, Killen, Kanter, Halperin, Engel and Currie2020; Allingbjerg et al., Reference Allingbjerg, Hansen, Secher and Thomsen2023; Vallof et al., Reference Vallöf, Kalafateli and Jerlhag2019a). Ex-4 administration into the CPu, representing dorsal striatal targeting, did not produce significant alterations in alcohol self-administration behaviour, likely reflecting the lower density or absence of GLP-1Rs in this region [F (3, 18) = 0.89, p = .44] (Allingbjerg et al., Reference Allingbjerg, Hansen, Secher and Thomsen2023). Additionally, Ex-4 administration did not significantly influence alcohol intake in the BLA, ArcN, or PVN (p > 0.05) (Colvin et al., Reference Colvin, Killen, Kanter, Halperin, Engel and Currie2020). Research also identified lack of significant effect on alcohol-related behaviours in the aVTA, pVTA, and LDTg, wherein Ex-4 infusion (0.0025 μg per hemisphere) had limited effects on CPP response, alcohol consumption, and alcohol preference (Vallof et al., Reference Vallöf, Kalafateli and Jerlhag2019a). In the aVTA, Ex-4 did not alter alcohol reward memory in conditioned place preference (CPP) compared to vehicle (t(13) = 0.85, P = 0.4111) and had no effect on alcohol intake (t(7) = 0.36, P = 0.7324) or preference (t(7) = 0.13, P = 0.9023) in high alcohol-consuming rats. Similarly, in the pVTA, Ex-4 did not affect CPP (t (12) = 0.61, P = 0.5503), alcohol intake (t (7) = 0.10, P = 0.9219), or preference (t (7) = 0.05, P = 0.9644) in high alcohol-consuming rats. In the LDTg, Ex-4 infusion had no effect on CPP in either low or high alcohol-consuming rats (t (44) = 0.54, P = 0.5914), with no differences in CPP between vehicle and Ex-4 groups in vehicle-conditioned rats (t (13) = 0.81, P = 0.4329). In low alcohol-consuming rats, Ex-4 had no effect on baseline alcohol intake (t (13) = 0.53, P = 0.5270) or preference (t (13) = 0.24, P = 0.8128). However, in high alcohol-consuming rats, Ex-4 significantly reduced alcohol intake (t (11) = 3.26, P = 0.0076) without affecting alcohol preference (t (11) = 1.42, P = 0.1847). These findings suggest Ex-4’s selective efficacy in reducing intake specifically in high-consuming phenotypes, with minimal effects on alcohol reward memory or preference across regions (Vallof et al., Reference Vallöf, Kalafateli and Jerlhag2019a).

The role of semaglutide on alcohol-related behaviors in preclinical studies

We identified 4 studies that reported on the effects of semaglutide on alcohol consumption in preclinical studies (Aranas et al., Reference Aranäs, Edvardsson, Shevchouk, Zhang, Witley, Blid Sköldheden, Zentveld, Vallöf, Tufvesson-Alm and Jerlhag2023; Marty et al., Reference Marty, Farokhnia, Munier, Mulpuri, Leggio and Spigelman2020; Chuong et al., Reference Chuong, Farokhnia, Khom, Pince, Elvig, Vlkolinsky, Marchette, Koob, Roberto, Vendruscolo and Leggio2023; Fink-Jensen et al., Reference Fink-Jensen, Wörtwein, Klausen, Holst, Hartmann, Thomsen, Ptito, Beierschmitt and Palmour2024). Aranas et al. (Reference Aranäs, Edvardsson, Shevchouk, Zhang, Witley, Blid Sköldheden, Zentveld, Vallöf, Tufvesson-Alm and Jerlhag2023) reported that acute and repeated semaglutide treatment significantly decreased alcohol intake in both male and female rats, with more pronounced reductions in males, suggesting a potential link between alcohol intake and body weight (P < 0.0001). Higher reductions in alcohol consumption were observed with higher dosages, indicating a dose-dependent association. Furthermore, semaglutide was also found to prevent post-withdrawal alcohol consumption (t (14) = 2.67, P = 0.0187, paired t-test, n = 15) and relapse drinking, with significant reductions reported at the 24th and 48th hour. Similarly, Chuong et al. (Reference Chuong, Farokhnia, Khom, Pince, Elvig, Vlkolinsky, Marchette, Koob, Roberto, Vendruscolo and Leggio2023) observed that semaglutide significantly reduced preference for both sweetened and unsweetened alcohol (P < 0.0001) across all doses, but significant reductions were reported for doses 0.003mg/kg, 0.01mg/kg, 0.03mg/kg, and 0.1mg/kg. While female rodents were found to consume more alcohol, no significant dose-sex interaction was reported. Despite the general efficacy of semaglutide, Fink-Jensen et al. (Reference Fink-Jensen, Wörtwein, Klausen, Holst, Hartmann, Thomsen, Ptito, Beierschmitt and Palmour2024) found that while alcohol consumption was significantly less in semaglutide-induced mice than vehicle controls (P = 0.0055), reductions only lasted through the second week (week 1: P = 0.0428, week 2: P = 0.0022, week 3: P = 0.0632). This finding suggests that the drug’s effect may be short-lived. Its transient effects were also supported by Marty et al. (Reference Marty, Farokhnia, Munier, Mulpuri, Leggio and Spigelman2020)’s findings, as researchers found that while semaglutide did reduce ethanol consumption and preference, the effects did not last more than two days post-drug administration. Furthermore, semaglutide demonstrated the ability to selectively reduce alcohol consumption without affecting other fluid intake, and these reductions were unaffected by the administration of Ex9-39, a GLP-1R antagonist, suggesting that its effects are independent.

The role of liraglutide on alcohol-related behavior in preclinical studies

With respect to liraglutide treatment, four studies exploring its effect on alcohol consumption were identified (Thomsen et al., Reference Thomsen, Holst, Molander, Linnet, Ptito and Fink-Jensen2018; Marty et al., Reference Marty, Farokhnia, Munier, Mulpuri, Leggio and Spigelman2020; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wang, Wang, Wang, Xing and Hölscher2024; Vallof et al., Reference Vallöf, Maccioni, Colombo, Mandrapa, Jörnulf, Egecioglu, Engel and Jerlhag2015). These studies explore the effects liraglutide has on consumption and preference, and the complexities of its underlying mechanisms. Findings by Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Wang, Wang, Wang, Xing and Hölscher2024) reported that reductions in alcohol consumption and preference were observed in alcohol treated mice treated with liraglutide for 6 weeks in comparison to the control group. Notably, these mice continued to exhibit these effects (relative to the control group) even after a two-week alcohol withdrawal period. Interestingly, total fluid intake was unaffected in both groups, suggesting that the reduction in alcohol preference was due to a selective effect on alcohol rather than general changes in fluid intake.

Correspondingly, Marty et al. (Reference Marty, Farokhnia, Munier, Mulpuri, Leggio and Spigelman2020)’s findings demonstrated that while liraglutide did reduce ethanol intake and preference (liraglutide: treatment × time-point interaction), the effects were transient and did not last for more than 2 days post-injection. The researchers proposed that, forasmuch as liraglutide may have increased water intake, it accounts for the reduction in alcohol preference as it may not have directly affected alcohol consumption.

In Thomsen et al. (Reference Thomsen, Holst, Molander, Linnet, Ptito and Fink-Jensen2018)’s study, liraglutide was observed to significantly reduce alcohol consumption compared to the vehicle group (F (1,22) = 17.3, p = 0.0004). This intake was related to day (F (11,242) = 5.08, p < 0.0001), and a treatment by day interaction (F (11,242) = 2.44, p = 0.007), indicating that the treatment had a sustained impact on alcohol consumption until the second day, which is in accordance with Marty et al (Reference Marty, Farokhnia, Munier, Mulpuri, Leggio and Spigelman2020)’s findings. Following the second day, a distinguishable rebound effect was briefly observed before alcohol intake resumed to vehicle-levels and the liraglutide treatment effect disappeared.

Vallof et al. (Reference Vallöf, Maccioni, Colombo, Mandrapa, Jörnulf, Egecioglu, Engel and Jerlhag2015) focused primarily on the effects of liraglutide on alcohol-associated conditioned place preference (CPP) and alcohol-induced dopamine release. Liraglutide treatment at a dosage of 0.1mg/kg significantly reduced alcohol-induced CPP and dopamine release (P = 0.0065). Liraglutide was also found to significantly reduce both alcohol intake (P < 0.01) and alcohol preference (P < 0.05), compared to the vehicle group. In high-alcohol consuming rats, liraglutide was found to significantly reduce alcohol consumption (P = 0.0056), without affecting water and total fluid intake, or alcohol preference. Conversely, no significant effect on alcohol intake (P = 0.1100) and alcohol preference (P = 0.5405) was observed in low-alcohol consuming rats, relative to the vehicle treatment. In a relapse-like drinking model, marked deprivation effects associated with liraglutide’s effects on alcohol intake and preference were detected in control group rats and absent in the treatment group after 24 hours. While the reductions in alcohol intake appeared transient over time, the effects were prolonged with longer treatment periods. Significant reductions were prominent in the earlier sessions but soon returned to baseline levels in later days, especially with the 0.05mg/kg dosage. The 0.1mg/kg group experienced prolonged effect responses for 2-3 days before returning to vehicle-like levels.

Clinical evidence on the influence of glp-1ra on alcohol-related behaviors

We identified two clinical studies evaluating the effects of GLP-1RAs (e.g., semaglutide and on alcohol consumption in patients diagnosed with AUD (Klausen et al., Reference Klausen, Jensen, Møller, Le Dous, Jensen, Zeeman, Johannsen, Lee, Thomsen, Macoveanu, Fisher, Gillum, Jørgensen, Bergmann, Enghusen Poulsen, Becker, Holst, Benveniste, Volkow and Fink-Jensen2022; Quddos et al., Reference Quddos, Hubshman, Tegge, Sane, Marti, Kablinger, Gatchalian, Kelly, DiFeliceantonio and Bickel2023). Results from the clinical literature indicate that there are mixed conclusions drawn on the role of GLP1-RAs on alcohol-related behaviours (e.g., alcohol consumption).

In a randomised control trial by Quddos et al. (Reference Quddos, Hubshman, Tegge, Sane, Marti, Kablinger, Gatchalian, Kelly, DiFeliceantonio and Bickel2023) (n = 153), semaglutide administration was associated with significant attenuation of alcohol consumption in comparison to control and non-treatment groups (p < 0.001). Notably, binge-drinking behaviours were reduced following treatment, as supported by the binomial model [i.e., Semaglutide vs. Control (B = −2.0517, SE = 0.6002, p < 0.001)]. Additionally, drinks per episode of regular usage were significantly reduced after participants initiated medication consumption (B = 2.3443, SE = 0.2668, p < 0.001). Quddos et al. (Reference Quddos, Hubshman, Tegge, Sane, Marti, Kablinger, Gatchalian, Kelly, DiFeliceantonio and Bickel2023) further identified significant reduction in AUDIT scores within (i.e., pre- and post- starting medications) and between (i.e., medicated vs control) groups following semaglutide administration.

In an intervention study, Klausen et al. (Reference Klausen, Jensen, Møller, Le Dous, Jensen, Zeeman, Johannsen, Lee, Thomsen, Macoveanu, Fisher, Gillum, Jørgensen, Bergmann, Enghusen Poulsen, Becker, Holst, Benveniste, Volkow and Fink-Jensen2022) reported that weekly exenatide administration did not significantly reduce heavy alcohol consumption days relative to the placebo group. Notwithstanding, an exploratory BMI subgroup analysis indicates that exenatide significantly decreased heavy drinking days by 23.6% (95% CI [−44.4, −2.7], P = 0.034) and reduced cumulative alcohol consumption by 1,205g within a month (95% CI [−2,206, −204], P = 0.026) in obese patients (BMI>30 kg/m2, n = 30) relative to placebo group. However, these trends were not observed in patients with a BMI<25 kg/m2 (n = 52). Instead, exenatide administration increased heavy drinking days by 27.5% (95% CI [4.7, 50.2], P = 0.024) relative to placebo, though fMRI Alcohol Cue Reactivity analysis revealed a significant reduction in cue reactivity in ventral striatum, dorsal striatum, and putamen after 26 weeks. Whole-brain analysis further revealed initial cue reactivity differentiation in certain regions compared to healthy controls, but these differences were resolved by week 26, with exenatide additionally reducing activation in the temporal lobe, hippocampus, and parahippocampus. Nonetheless, there is not adequate information on the effects of GLP-1RAs on alcohol consumption and associated behaviours.

Discussion

Extensive literature provides evidence associating GLP-1RAs activity and modulation of alcohol-related behaviours, mediated by their interaction with key neurobiological pathways (Shirazi et al., Reference Shirazi, Dickson and Skibicka2013; Colvin et al., Reference Colvin, Killen, Kanter, Halperin, Engel and Currie2020; Vallof et al., Reference Vallöf, Kalafateli and Jerlhag2019a; Vallof et al., Reference Vallöf, Vestlund and Jerlhag2019b). Particularly, GLP-1RAs modulate the mesolimbic dopamine system, a critical circuit involved in reward and reinforcement processes, by targeting GLP-1R expressed in regions such as the NAc and VTA (Allingbjerg et al., Reference Allingbjerg, Hansen, Secher and Thomsen2023; Aranas et al., Reference Aranäs, Edvardsson, Shevchouk, Zhang, Witley, Blid Sköldheden, Zentveld, Vallöf, Tufvesson-Alm and Jerlhag2023; Colvin et al., Reference Colvin, Killen, Kanter, Halperin, Engel and Currie2020; Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, McNally and Ong2020; Vallof et al., Reference Vallöf, Kalafateli and Jerlhag2019a). Furthermore, GLP-1RAs attenuate alcohol-induced dopamine release in theseregions, subsequently reducing alcohol preference, consumption, and associated reinforcing effects (Aranas et al., Reference Aranäs, Edvardsson, Shevchouk, Zhang, Witley, Blid Sköldheden, Zentveld, Vallöf, Tufvesson-Alm and Jerlhag2023; Egecioglu et al., Reference Egecioglu, Steensland, Fredriksson, Feltmann, Engel and Jerlhag2013; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wang, Wang, Wang, Xing and Hölscher2024; Marty et al., Reference Marty, Farokhnia, Munier, Mulpuri, Leggio and Spigelman2020; Shirazi et al., Reference Shirazi, Dickson and Skibicka2013; Thomsen et al., Reference Thomsen, Dencker, Wörtwein, Weikop, Egecioglu, Jerlhag, Fink-Jensen and Molander2017; Vallof et al., Reference Vallöf, Maccioni, Colombo, Mandrapa, Jörnulf, Egecioglu, Engel and Jerlhag2015; Vallof et al., Reference Vallöf, Kalafateli and Jerlhag2019a; Vallof et al., Reference Vallöf, Vestlund and Jerlhag2019b). As such, these agonists may influence alcohol-related behaviours through their effects on brain regions, including the hypothalamus, amygdala, and HPC, which have known effects on stress, memory, and emotional responses relative to alcohol cues. These mechanisms collectively support the therapeutic potential of GLP-1RAs in altering alcohol and reward-related behaviours in pre-clinical models and clinical population.

Despite evidence supporting GLP-1RA mediated modulation of alcohol-related behaviours, notable considerations remain. Particularly, pre-clinical studies demonstrate that the efficacy of GLP-1RAs in reducing alcohol-related behaviours is dependent on the administration site. Brain regions such as the NAc and VTA consistently yield significant reductions in alcohol consumption and preference, reflecting their central role in the reward circuitry (Colvin et al., Reference Colvin, Killen, Kanter, Halperin, Engel and Currie2020; Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, McNally and Ong2020; Allingbjerg et al., Reference Allingbjerg, Hansen, Secher and Thomsen2023; Vallof et al., Reference Vallöf, Kalafateli and Jerlhag2019a). For instance, exenatide administered directly into the NAc or VTA effectively attenuates alcohol self-administration and dopamine release, highlighting these regions as optimal targets for GLP-1RA interventions. Conversely, GLP-1RA administration in regions such as the CPu, BLA, ArcN, and PVN appears less effective or altogether ineffective (Colvin et al., Reference Colvin, Killen, Kanter, Halperin, Engel and Currie2020; Allingbjerg et al., Reference Allingbjerg, Hansen, Secher and Thomsen2023; Vallof et al., Reference Vallöf, Kalafateli and Jerlhag2019a). This may reflect lower GLP-1R density or limited involvement of these regions in alcohol reward pathways (Allingbjerg et al., Reference Allingbjerg, Hansen, Secher and Thomsen2023). These findings emphasise the importance of targeted administration strategies to maximise the efficacy of GLP-1RAs in preclinical models and potentially in clinical settings.

Another consideration is the influence of GLP-1RAs on alcohol-related behaviours varying across sex and drinking phenotypes. Male rodents generally exhibit greater reductions in alcohol consumption and preference following GLP-1RA administration compared to females, suggesting a sex-dependent response likely influenced by hormonal or neurochemical differences (Díaz-Megido & Thomsen, Reference Díaz-Megido and Thomsen2023). However, a few examined studies found no significant interaction between dose and sex, they observed a sex- independent relationship. Furthermore, GLP-1RAs appear more effective in high-alcohol-consuming phenotypes, reducing alcohol-related behaviours to a greater extent than in low-consuming counterparts. This variability emphasises the need for additional examinations into the biological underpinnings of these differences to inform personalised treatment approaches.

In addition, clinical studies evaluating GLP-1RAs for AUD patients demonstrated mixed findings. While semaglutide has demonstrated promising reductions in alcohol consumption and binge-drinking behaviours, the effects of exenatide appear to vary based on patient characteristics, such as body mass index). For instance, obese patients exhibited significant reductions in heavy drinking days and alcohol consumption with exenatide treatment, whereas non-obese patients showed minimal or even adverse effects. These contrasting results suggest that GLP-1RA efficacy may depend on individual variability, necessitating further investigation to identify patient subgroups most likely to benefit from treatment.

A recurring limitation observed in assessed preclinical and clinical studies is the transient nature of GLP-1RA effects on alcohol-related behaviours. While significant reductions in alcohol consumption and preference are often observed initially, these effects diminish over time (Marty et al., Reference Marty, Farokhnia, Munier, Mulpuri, Leggio and Spigelman2020; Fink-Jensen et al., Reference Fink-Jensen, Wörtwein, Klausen, Holst, Hartmann, Thomsen, Ptito, Beierschmitt and Palmour2024; Vallof et al., Reference Vallöf, Maccioni, Colombo, Mandrapa, Jörnulf, Egecioglu, Engel and Jerlhag2015), potentially due to receptor desensitisation or compensatory neuroadaptations. Receptor desensitisation and neuroadaptations may limit the long-term efficacy of GLP-1RAs. As such, future research should further evaluate strategies to mitigate tolerance, such as dose escalation protocols, intermittent dosing schedules, or combination therapies targeting complementary pathways.

Other possible explanations may stem from the intricacies of the neuroendocrine system, where prolonged modifications in reward pathways are counterbalanced by compensatory hormonal fluctuations. Furthermore, the progressive reinstatement of alcohol intake may be facilitated by various factors that are not sufficiently regulated by the pharmacological activity of GLP-1RAs. This limitation highlights the need for longitudinal studies to evaluate the sustained efficacy of GLP-1RAs and explore strategies to mitigate tolerance, such as dose adjustments or combination therapies.

Lastly, another notable limitation of the current literature (Erbil et al., Reference Erbil, Eren, Demirel, Küçüker, Solaroğlu and Eser2019) is the variability in the neuroprotective effects of various GLP-1 analogues. Evidence suggests that these effects are largely dose-dependent, where higher doses are associated with more significant neurodegenerative process reversals; such effects could have profound and similar implications in reward pathways and neural circuits involved in neurodegeneration and substance abuse. Additionally, treatment combinations have been suggested to yield greater efficacy, however most of the reviewed studies did not explore the potential synergistic effects combining different analogues, which is an aspect that could have vital implications in understanding their impact on alcohol-related behaviours and reward pathways. The omission of such combination therapies in these studies results in a gap in research, warranting further exploration on therapeutic avenues regarding GLP-1RAs and addiction interventions.

Conclusion

Results from assessed preclinical and clinical studies underscore the potential of GLP-1RAs in attenuating alcohol-related behaviours, though the extent and consistency of these effects vary across experimental models and patient populations. Extant preclinical studies suggest that GLP-1RAs (i.e., exenatide, semaglutide, and liraglutide) attenuate alcohol consumption, preference, and alcohol-induced neurochemical responses in rodent models, with nuanced differences influenced by dosage, administration route, and target brain regions. Notably, the efficacy of these agents appears selective of high-alcohol-consuming phenotypes and specific brain regions such as NAc and VTA. However, discrepancies in findings, including the transient nature of effects and region-dependent variability, emphasise the need for further mechanistic studies into GLP-1RA’s influence on alcohol-related pathways. Additionally, clinical evidence, while limited, has yielded mixed conclusions regarding the influence of GLP-1RAs on alcohol-associated behaviours. While semaglutide has shown promise in reducing alcohol consumption and binge-drinking episodes, the effects of exenatide appear to be influenced by patient characteristics such as BMI, suggesting variability in treatment response. These findings emphasise the need for additional clinical studies to clarify the therapeutic efficacy of GLP-1RAs in addressing AUD. Recent analysis on GLP-1 suggests an association with suicide, but with no causal effects (McIntyre et al., Reference McIntyre, Mansur, Rosenblat and Angela2023; McIntyre, Reference McIntyre2024; McIntyre et al., Reference McIntyre, Angela, Rosenblat, Teopiz and Mansur2024; McIntyre et al., Reference McIntyre, Mansur, Rosenblat, Rhee, Cao, Teopiz, Wong, Le, Ho and Kwan2025). Further research should concentrate on elucidating the mechanisms underlying these effects, identifying biomarkers of treatment response, and optimising intervention strategies to enhance clinical applicability.

Lastly, this review does not examine the role of GLP-1R antagonists, inhibition techniques, or genetic knockouts to explicitly confirm whether observed effects on alcohol-related behaviours are directly mediated through GLP-1R signalling. Without these studies, it remains uncertain whether GLP-1RAs exert their effects through GLP-1 receptor activation or if alternative pathways contribute to the behavioural outcomes. As such, this gap necessitates further incorporation of antagonist, inhibitory, or genetic techniques to confirm the role of GLP-1R activation through GLP-1RAs in alcohol-associated behaviours. Future studies should integrate antagonist administration or genetic knockout models to delineate the precise role of GLP-1R signalling, clarifying mechanistic specificity and excluding confounding influences. Addressing this gap is essential for refining therapeutic strategies, optimising intervention efficacy, and identifying potential off-target mechanisms influencing alcohol-related behaviours.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/neu.2025.6.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contribution

Conceptualisation and Methodology: Yang Jing Zheng and Roger S McIntyre.

Investigation: Yang Jing Zheng, Hezekiah Au, and Crystaleene Soegiharto.

Formal analysis and Visualisation: Yang Jing Zheng and Crystaleene Soegiharto.

Writing - Original Draft: Yang Jing Zheng, Hezekiah Au, and Crystaleene Soegiharto.

Writing - Review and Editing: All authors.

Financial statement

This paper was not funded by any entity.

Competing interests

Dr. Roger S. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) and the Milken Institute; speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Neumora Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sage, Biogen, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Neurawell, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Viatris, Abbvie and Atai Life Sciences. Dr. Roger S. McIntyre is a CEO of Braxia Scientific Corp. Kayla M. Teopiz has received fees from Braxia Scientific Corp. Dr. Taeho Greg Rhee was supported in part by the National Institute on Aging (#R21AG070666; R21AG078972; R01AG088647), National Institute of Mental Health (#R01MH131528), National Institute on Drug Abuse (#R21DA057540), and Health Resources and Services Administration (#R42MC53154-01-00). Dr. Rhee serves as a review committee member for Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and has received honoraria payments from PCORI and SAMHSA. Dr. Rhee has also served as a stakeholder/consultant for PCORI and received consulting fees from PCORI. Dr. Rhee serves as an advisory committee member for International Alliance of Mental Health Research Funders (IAMHRF). Yang Jing Zheng, Crystaleene Soegiharto, Hezekiah Au, Kyle Valentino, Gia Han Le, Sabrina Wong, Hernan F. Guillen-Burgos, and Bing Cao have no conflicts to declare.