Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 March 2024

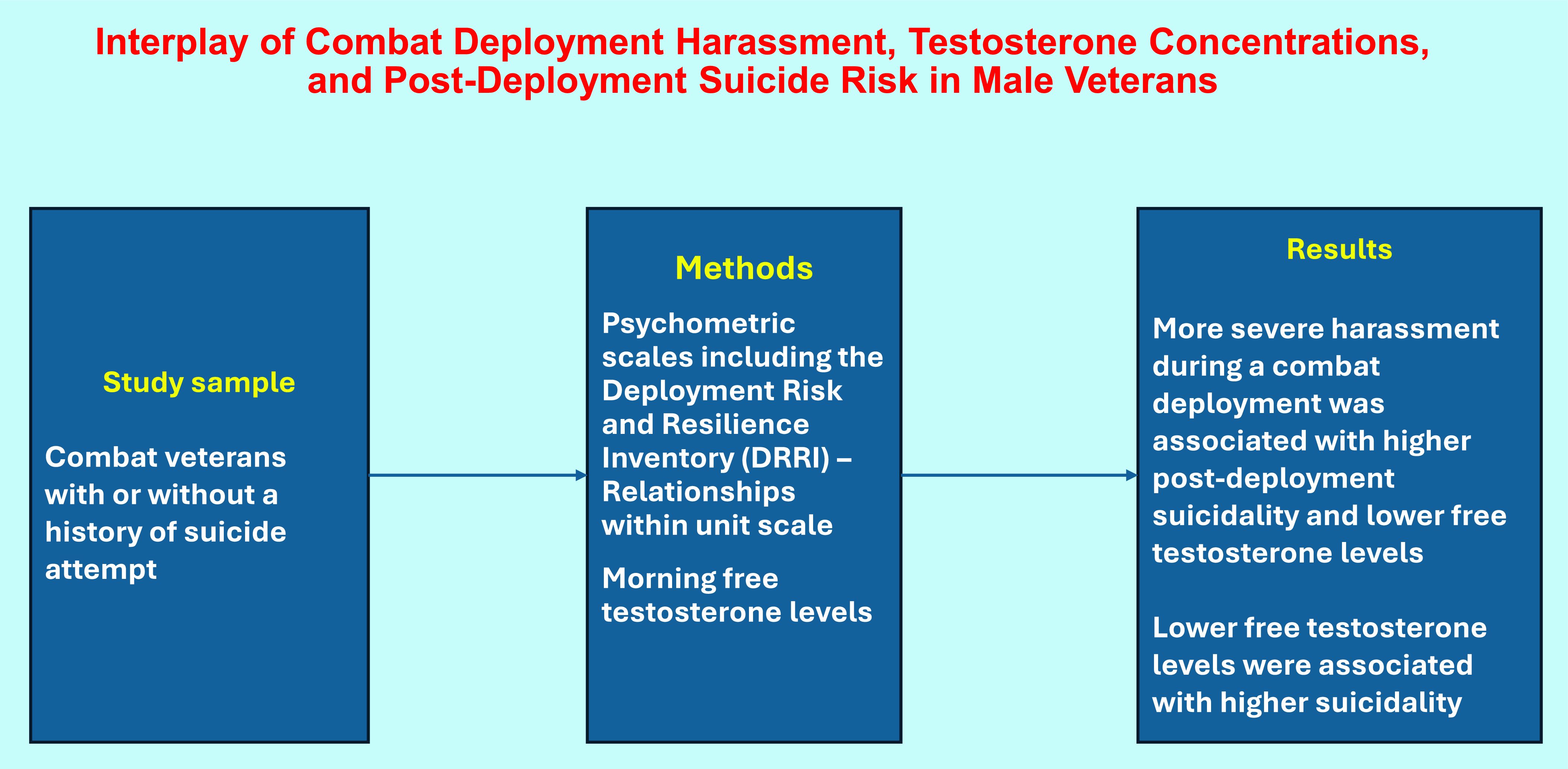

Many combat veterans exhibit suicidal ideation and behaviour, but the relationships among experiences occurring during combat deployment and suicidality are still not fully understood. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that harassment during a combat deployment is associated with post-deployment suicidality and testosterone function.

Male combat veterans who made post-deployment suicide attempts and demographically matched veterans without a history of suicide attempts were enrolled in the study. Demographic and clinical parameters of study participants were assessed and recorded. Study participants were interviewed by a trained clinician using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), the Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory (DRRI) – Relationships within unit scale, the Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI), and the Brown–Goodwin Aggression Scale. Free testosterone levels were assessed in morning blood samples.

DRRI harassment scores were higher and free testosterone levels were lower among suicide attempters in comparison with non-attempters. In the whole sample, DRRI harassment scores positively correlated with SSI scores and negatively correlated with free testosterone levels. Free testosterone levels negatively correlated with SSI scores. Aggression scale scores positively correlated with DRRI harassment scores among non-attempters but not among attempters.

Our observations that harassment scores are associated with suicidality and testosterone levels, and suicidality is associated with testosterone levels may indicate that there is a link between deployment harassment, testosterone function and suicidality.