Summations

-

• Glucagon-like peptide-1 and its receptor agonism was positively associated with neurogenesis.

-

• Changes in neurogenesis were observed in the hippocampus, dentate gyrus, olfactory bulb, and medial striatum.

Considerations

-

• No human studies were identified, limiting the ability to extend the findings to humans.

-

• Animal models vary in species and disease models, which may introduce confounding effects.

-

• Markers for neurogenesis of disparate neuronal populations varied across studies, which may impact the consistency of the results.

Introduction

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is a gut-derived incretin hormone indicated for antidiabetic therapy by promoting insulin secretion and inhibition of glucagon secretion (Lutz & Osto, Reference Lutz and Osto2016). GLP-1 receptors are broadly distributed both peripherally (e.g., on pancreatic β cells) and within the central nervous system (Lee & Lee, Reference Lee and Lee2017; Muscogiuri et al., Reference Muscogiuri, DeFronzo, Gastaldelli and Holst2017). Extant literature has reported that GLP-1 receptors are expressed on neurons in regions such as the paraventricular nucleus, hippocampus, and preproglucagon cells in the olfactory bulb (Katsurada et al., Reference Katsurada, Maejima, Nakata, Kodaira, Suyama, Iwasaki, Kario and Yada2014; Montaner et al., Reference Montaner, Denom, Simon, Jiang, Holt, Brierley, Rouch, Foppen, Kassis, Jarriault, Khan, Eygret, Mifsud, Hodson, Broichhagen, Van Oudenhove, Fioramonti, Gault, Cota, Reimann, Gribble, Migrenne-Li, Trapp, Gurden and Magnan2024; Canário et al., Reference Canário, Crisóstomo, Moreno, Duarte, Duarte, Ribeiro, Caramelo, Gomes, Matafome, Oliveira and Castelo-Branco2024).

Neurogenesis is a process described as the formation of neurons through stem and progenitor cell proliferation, occurring mainly in the subgranular zone within the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus and subventricular zone (SVZ) of lateral ventricles (Cope & Gould, Reference Cope and Gould2019; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Guo and Zhou2023a). This process is characterised by the proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells via symmetrical division to form new neural stem cells, and asymmetric division to produce radial glial cells (Shimojo et al., Reference Shimojo, Ohtsuka and Kageyama2011). The newly proliferated radial glial cells can further divide into neuroblasts and astrocytes through asymmetric division, subsequently integrating into existing neural circuits (Shimojo et al., Reference Shimojo, Ohtsuka and Kageyama2011; Braun & Jessberger, Reference Braun and Jessberger2014; Ihunwo et al., Reference Ihunwo, Tembo and Dzamalala2016). Neuronal differentiation and proliferation involves the cAMP Response Element-Binding Protein (CREB) and Notch signalling pathways (Merz et al., Reference Merz, Herold and Lie2011; Bagheri-Mohammadi, Reference Bagheri-Mohammadi2021). These processes are modulated by various kinases, including protein kinase A (PKA) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Jo, Eun and Ahn Jo2003; Bagheri-Mohammadi, Reference Bagheri-Mohammadi2021).

Extant literature identified that GLP-1 and GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) can exert neuroproliferative effects whilst being associated with increased neurogenesis in preclinical models (Velmurugan et al., Reference Velmurugan, Bouchard, Mahaffey and Pugazhenthi2012; McIntyre et al., Reference McIntyre, Powell, Kaidanovich-Beilin, Soczynska, Alsuwaidan, Woldeyohannes, Kim and Gallaugher2013; Vaccari et al., Reference Vaccari, Grotto, Pereira, de Camargo, Lopes and Wei2021). It is hypothesised that GLP-1 subserves neuroproliferative effects through the action of PKA and PI3K pathways (Li et al., Reference Li, Tweedie, Mattson, Holloway and Greig2010). Notably, the binding of GLP-1 RAs result in increases in cAMP and PI3K, wherein the activation of these secondary messengers lead to activation of factors such as CREB and the Notch signalling pathways, resulting in increased synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Jo, Eun and Ahn Jo2003; Bagheri-Mohammadi, Reference Bagheri-Mohammadi2021; Dworkin & Mantamadiotis, Reference Dworkin and Mantamadiotis2010; Ren et al., Reference Ren, Xue, Wu, Yang and Wu2021). Notwithstanding, the role of GLP-1 and GLP-1 RAs on neurogenesis has not been adequately explored.

Herein, we examine the effects of GLP-1 RAs on neurogenesis across both preclinical and clinical paradigms. Our goal is to provide a comprehensive update on the impact of each GLP-1 RA in neurogenesis, while highlighting their potential therapeutic applications in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s Disease (AD).

Methods

Search strategy

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) was utilised to conduct this study (Page et al., Reference Page, Moher, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, McDonald, McGuinnes, Stewart, Thomas, Tricco, Welch, Whiting and McKenzie2021). Relevant articles were systematically searched using Web of Science, OVID (MedLINE, Embase, AMED, PsychInfo, JBI EBP), and PubMed from database inception to June 26, 2024. The search string used for the search included: (“GLP-1” OR “Glucagon-Like Peptide-1” OR “Glucagon-Like Peptide 1” OR “GLP-1 Agonist” OR “Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Agonist” OR “Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Agonist” OR “Semaglutide” OR “Ozempic” OR “Rybelsus” OR “Wegovy” OR “Dulaglutide” OR “Trulicity” OR “Exenatide” OR “Byetta” OR “Bydureon” OR “Liraglutide” OR “Lixisenatide” OR “Tirzepatide”) AND (“Neurogenesis” OR “Neuron* Proliferation). Separate searches were conducted on Google Scholar and from reference lists to ensure all articles relevant to the topic were captured.

Study selection and inclusion criteria

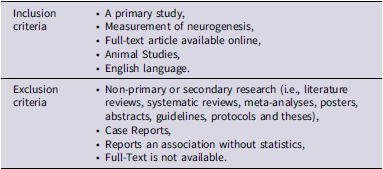

Articles obtained from the systematic search were screened through the Covidence platform, wherein duplicate articles were removed (Covidence, 2024). Two reviewers (H.A. and Y.J.Z.) independently screened the titles and abstracts based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). Primary articles that reported on changes in neurogenesis as a result of GLP-1 prescription or administration were retrieved for full-text screening by two reviewers (H.A. and Y.J.Z.) (Table 1). All conflicts were resolved via discussion, and articles deemed eligible by both reviewers were selected for data extraction.

Table 1. Eligibility criteria

Data extraction

A piloted data extraction template was used to organise and obtain data from included studies. Information to be extracted was established a priori, including (1) author, (2) study type, (3) sample size, (4) stains, (5) outcomes of interest. Two independent reviewers (H.A. and Y.J.Z.) conducted data extraction, wherein all conflicts were resolved through discussion. Outcomes of interest pertained to changes in neurogenesis associated with GLP-1 prescription or administration.

Quality assessments

Quality assessments were conducted using the SYRCLE’s risk of bias analysis tool for animal studies (Hooijmans et al., Reference Hooijmans, Rovers, de Vries, Leenaars, Ritskes-Hoitinga and Langendam2014). Relevant literature was assessed by two independent reviewers (H.A. and Y.J.Z.), wherein the risk of bias was evaluated, and all conflicts were resolved following discussions. Further information on inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as a summary table, can be found as supplementary material (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2. Characteristics of studies examining effect of GLP-1 and GLP-1 RAs on neurogenesis in animal models

BrdU, Bromodeoxyuridine; DCX, Doublecortin; Ki67, Antigen Kiel 67; NeuN, Hexaribonucleotide Binding Protein-3; Ex-4, Exendin-4; MCAO, Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion; Iba1, Ionized Calcium-binding Adapter.

Results

Search results

A systematic search generated a total of 162 studies, wherein 7 duplicates were identified manually, and 60 duplicates were identified by Covidence. 95 studies underwent abstract and title screening, with 65 articles deemed irrelevant. In accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 30 full-text studies were assessed for eligibility, of which, 13 were excluded due to wrong outcomes (n = 8), wrong study designs (n = 3), wrong comparator (n = 1), and wrong intervention (n = 1), yielding a total of 17 studies for further analysis (Figure 1, Table S2). Although animal and human studies were eligible for inclusion, the search only yielded animal studies.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram of literature search ( Covidence, 2024).

Methodological quality

Quality assessment of the included studies was conducted using the SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies (Hooijmans et al., Reference Hooijmans, Rovers, de Vries, Leenaars, Ritskes-Hoitinga and Langendam2014). Studies utilizing animal cell culture generated ‘not reported’ (NR) or ‘X’ notations, as some prompts were not applicable or not reported within the studies. However, as these studies derive cell culture from live animals, the SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool was used.

All of the included studies assessed preclinical literature, demonstrating low attrition and reporting bias. Common limitations of selected studies include insufficient detection bias and blinding procedures, including allocation concealment, random housing, and random outcome assessment domains.

The bias assessment in animal model studies revealed distinct patterns that correspond to their overall quality ratings. Studies assessed as “Good,” such as those conducted by Belsham et al., (Reference Belsham, Fick, Dalvi, Centeno, Chalmers, Lee, Wang, Drucker and Koletar2009); McGovern et al., (Reference McGovern, Hunter and Hölscher2012); Pathak et al., (Reference Pathak, Pathak, Gault, McClean, Irwin and Flatt2018); Sampedro et al., (Reference Sampedro, Bogdanov, Ramos, Solà-Adell, Turch, Simó-Servat, Lagunas, Simó and Hernández2019); Solmaz et al., (Reference Solmaz, Çınar, Yiğittürk, Çavuşoğlu, Taşkıran and Erbaş2015); Weina et al., (Reference Weina, Yuhu, Christian, Birong, Feiyu and Le2018); and Yang et al., (Reference Yang, Feng, Zhang, Li, Wang, Ji, Li and Hölscher2019), generally exhibit a lower risk of bias with most items adequately reported, despite occasional limitations in areas like random housing or random outcome assessment. In contradistinction, studies rated as ‘Fair’, including those by Bertilsson et al.,(Reference Bertilsson, Patrone, Zachrisson, Andersson, Dannaeus, Heidrich, Kortesmaa, Mercer, Nielsen, Rönnholm and Wikström2007), Darsalia et al., (Reference Darsalia, Mansouri, Ortsäter, Olverling, Nozadze, Kappe, Iverfeldt, Tracy, Grankvist, Sjöholm and Patrone2012); Hamilton et al., (Reference Hamilton, Patterson, Porter, Gault and Holscher2011), Lennox et al., (Reference Lennox, Porter, Flatt and Gault2013), Parthsarathy & Hölscher (Reference Parthsarathy and Hölscher2013), Ren et al., (Reference Ren, Xue, Wu, Yang and Wu2021); and Zhao et al., (Reference Zhao, Yu, Ping, Xu, Li, Zhang and Li2022), often show a higher number of items marked as “Not Reported” or “No,” particularly in baseline characteristics, allocation concealment, and random housing. Additionally, the study by Hunter & Hölscher (Reference Hunter and Hölscher2012) was rated ‘‘Poor’’ as it consistently demonstrate significant bias with multiple items inadequately reported, highlighting the necessity for rigorous methodology to ensure comparability and reliability in animal research (Table S1). This pattern emphasises the link between comprehensive reporting and a lower risk of bias, underscoring the crucial significance of thorough methodological transparency in producing high-quality, reliable scientific outcomes.

GLP-1 effects on neurogenesis in animal models

We have identified three studies examining the effects of GLP-1 and neurogenesis (Table 2) (Lennox et al., Reference Lennox, Porter, Flatt and Gault2013; McGovern et al., Reference McGovern, Hunter and Hölscher2012; Sampedro et al., Reference Sampedro, Bogdanov, Ramos, Solà-Adell, Turch, Simó-Servat, Lagunas, Simó and Hernández2019). Lennox et al., (Reference Lennox, Porter, Flatt and Gault2013) identified an association between (Val8)GLP-1-Glu-RA administration and a 30% increase in BrdU-positive cells (p < 0.05) within the granular cell layer of the dentate gyrus of mice in comparison to saline controls (Lennox et al., Reference Lennox, Porter, Flatt and Gault2013). The increase in BrdU-positive cells indicate a significant difference in mature neuronal populations between GLP-1 administration and saline controls (Lennox et al., Reference Lennox, Porter, Flatt and Gault2013). This trend was in accordance with results from McGovern et al., (Reference McGovern, Hunter and Hölscher2012), wherein (Val8)GLP-1-Glu-PA administration was significantly associated with increases in BrdU-positive cells (p < 0.05) and DCX-positive cells (p < 0.05) in mice dentate gyrus (McGovern et al., Reference McGovern, Hunter and Hölscher2012). Similarly, Sampedro et al., (Reference Sampedro, Bogdanov, Ramos, Solà-Adell, Turch, Simó-Servat, Lagunas, Simó and Hernández2019) reported significant increases in neurogenesis ascertained by marker Ki-67 in the ganglion cell layer, inner nuclear layer, inner plexiform layer, outer nuclear layer, and the outer plexiform layer (p < 0.05) of obese mice treated with GLP-1 in comparison to controls (Sampedro et al., Reference Sampedro, Bogdanov, Ramos, Solà-Adell, Turch, Simó-Servat, Lagunas, Simó and Hernández2019). Notably, GLP-1 administration was also associated with upregulation of survival pathways glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta (GSK3β) (p < 0.05) and B-cell lymphoma-extra-large protein (Bcl-xL) (p < 0.05) (Sampedro et al., Reference Sampedro, Bogdanov, Ramos, Solà-Adell, Turch, Simó-Servat, Lagunas, Simó and Hernández2019). Taken together, these results suggest that GLP-1 increases neurogenesis in various regions of the brain and provides mechanistic insight on the pathways in which GLP-1 can modulate neurogenesis (Lennox et al., Reference Lennox, Porter, Flatt and Gault2013; McGovern et al., Reference McGovern, Hunter and Hölscher2012; Sampedro et al., Reference Sampedro, Bogdanov, Ramos, Solà-Adell, Turch, Simó-Servat, Lagunas, Simó and Hernández2019).

Association between GLP-1 RAs and neurogenesis in animal models

To understand the effects of GLP-1 RAs and neurogenesis in animal models, we have identified 13 studies (Table 2). Of the studies included herein, Hamilton et al., (Reference Hamilton, Patterson, Porter, Gault and Holscher2011) characterised the effect of both exenatide and liraglutide on neurogenesis.

Effect of exenatide on neurogenesis in animal models

Findings from Solmaz et al., (Reference Solmaz, Çınar, Yiğittürk, Çavuşoğlu, Taşkıran and Erbaş2015) identified significantly higher hippocampal neuronal count (p < 0.05) in mice treated with exenatide in comparison to saline (Solmaz et al., Reference Solmaz, Çınar, Yiğittürk, Çavuşoğlu, Taşkıran and Erbaş2015). These results were replicated by Pathak et al., (Reference Pathak, Pathak, Gault, McClean, Irwin and Flatt2018), wherein exendin-4 (Ex-4) administration in mice was associated with significantly increased DCX-positive cell count in comparison to controls (p < 0.001). The aforementioned trends accord with the results by Darsalia et al., (Reference Darsalia, Mansouri, Ortsäter, Olverling, Nozadze, Kappe, Iverfeldt, Tracy, Grankvist, Sjöholm and Patrone2012) wherein Ex-4 treatment over two weeks was associated with a 50% in neuroblast production when compared to PBS-treated rats (p < 50%).

Furthermore, analysis using Ki67 staining identified that Ex-4 treatment over two weeks was associated with a two-fold increase in proliferating cells in the SVZ of the hippocampus and dentate gyrus (p < 0.05) (Darsalia et al., Reference Darsalia, Mansouri, Ortsäter, Olverling, Nozadze, Kappe, Iverfeldt, Tracy, Grankvist, Sjöholm and Patrone2012). However, no effects of Ex-4 were reported when a NeuN/BrdU double marker was used to examine the effects of Ex-4 treatment (Darsalia et al., Reference Darsalia, Mansouri, Ortsäter, Olverling, Nozadze, Kappe, Iverfeldt, Tracy, Grankvist, Sjöholm and Patrone2012). Notwithstanding, Hamilton et al., (Reference Hamilton, Patterson, Porter, Gault and Holscher2011) reported a 65 and 63% increase in BrdU-positive cells in Ex-4 treated obese (ob/ob) mice and diabetic (db/db) mice (mice with a point mutation causing leptin receptor deficiency) (p < 0.001) in comparison to saline controls, respectively (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Patterson, Porter, Gault and Holscher2011; Suriano et al., Reference Suriano, Vieira-Silva, Falony, Roumain, Paquot, Pelicaen, Régnier, Delzenne, Raes, Muccioli, Van Hul and Cani2021). High-fat diet mice treated with Ex-4 also exhibited a significant increase in DCX-positive neurons in comparison to saline-treated mice (p < 0.001) (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Patterson, Porter, Gault and Holscher2011). These trends are further reinforced by findings from Bertilsson et al., (Reference Bertilsson, Patrone, Zachrisson, Andersson, Dannaeus, Heidrich, Kortesmaa, Mercer, Nielsen, Rönnholm and Wikström2007), wherein bis in die administration of Ex-4 for 7 days in rats was associated with a near two-fold and 70% increase in BrdU-positive cells in the SVZ and DCX-positive cells in the medial striatum, respectively (p < 0.01) (Bertilsson et al., Reference Bertilsson, Patrone, Zachrisson, Andersson, Dannaeus, Heidrich, Kortesmaa, Mercer, Nielsen, Rönnholm and Wikström2007). Consistent with the aforementioned trends, results from Belsham et al., (Reference Belsham, Fick, Dalvi, Centeno, Chalmers, Lee, Wang, Drucker and Koletar2009) identified that Ex-4 treatment over a one-week period was associated with a two-fold increase in BrdU-positive cells (p < 0.05) in mice (Belsham et al., Reference Belsham, Fick, Dalvi, Centeno, Chalmers, Lee, Wang, Drucker and Koletar2009). These findings suggest the presence of a positive association between exenatide and neurogenesis.

Geniposide effect on neurogenesis in animal models

There is currently insufficient information on the effects of geniposide on neurogenesis. Notwithstanding, an experimental study by Sun et al., (Reference Sun, Jia, Yang, Ren and Wu2021) examined the effect of geniposide in mice. Findings suggest that geniposide mediated an increase in DCX-positive cells and dendrites in mice treated with geniposide in comparison to controls (p < 0.05). Due to the limited data available, a comprehensive evaluation of geniposide’s effect on neurogenesis cannot be made.

Liraglutide effect on neurogenesis in animal models

We identified 6 studies examining the role of liraglutide in neurogenesis (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Patterson, Porter, Gault and Holscher2011; Hunter & Hölscher, Reference Hunter and Hölscher2012; Parthsarathy & Hölscher, Reference Parthsarathy and Hölscher2013; Weina et al., Reference Weina, Yuhu, Christian, Birong, Feiyu and Le2018; Salles et al., Reference Salles, Calió, Afewerki, Pacheco-Soares, Porcionatto, Hölscher and Lobo2018; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Yu, Ping, Xu, Li, Zhang and Li2022). Weina et al., (Reference Weina, Yuhu, Christian, Birong, Feiyu and Le2018) reported a significant increase in the density of DCX-positive immature neurons in mice injected with corticosterone and liraglutide in comparison with mice injected with corticosterone and saline (p = 0.0456). Additionally, ob/ob mice treated with liraglutide exhibited a 65% increase in BrdU-positive cells, wherein db/db mice treated with liraglutide exhibited an 88% increase in BrdU-positive cells in comparison to saline controls (p < 0.001) (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Patterson, Porter, Gault and Holscher2011). Similarly, a significant increase in neuronal count in the dentate gyrus of mice injected with liraglutide in comparison to controls (p < 0.05) was observed (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Yu, Ping, Xu, Li, Zhang and Li2022). Simultaneously, liraglutide administration was also associated with increased activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (p < 0.05) (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Yu, Ping, Xu, Li, Zhang and Li2022). Additionally, liraglutide administration was associated with significant increases in cAMP levels in comparison to controls (p < 0.05) (Hunter & Hölscher, Reference Hunter and Hölscher2012). In a separate study by Salles et al., (Reference Salles, Calió, Afewerki, Pacheco-Soares, Porcionatto, Hölscher and Lobo2018), liraglutide administration was associated with increases in DCX-marked neuroblasts of wild-type mice (p < 0.05) and APP/PS1 mice (p < 0.01) in the SVZ when compared to saline treatment. In contradistinction, liraglutide did not significantly change levels of GFAP-marked astrocytes (p > 0.05) (Salles et al., Reference Salles, Calió, Afewerki, Pacheco-Soares, Porcionatto, Hölscher and Lobo2018).-catenin pathway (p < 0.05) (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Yu, Ping, Xu, Li, Zhang and Li2022). Additionally, liraglutide administration was associated with significant increases in cAMP levels in comparison to controls (p < 0.05) (Hunter & Hölscher, Reference Hunter and Hölscher2012). In a separate study by Salles et al., (Reference Salles, Calió, Afewerki, Pacheco-Soares, Porcionatto, Hölscher and Lobo2018), liraglutide administration was associated with increases in DCX-marked neuroblasts of wild-type mice (p < 0.05) and APP/PS1 mice (p < 0.01) in the SVZ when compared to saline treatment. In contradistinction, liraglutide did not significantly change levels of GFAP-marked astrocytes (p > 0.05) (Salles et al., Reference Salles, Calió, Afewerki, Pacheco-Soares, Porcionatto, Hölscher and Lobo2018).

Parthsarathy & Hölscher (Reference Parthsarathy and Hölscher2013) identified that wild-type mice treated with liraglutide over a week exhibited increased cell proliferation at 3 months (90%), 6 months (63%), 12 months (114%), and 15 months (137%) of age (p < 0.05) in comparison to saline controls. Similarly, an increase in DCX-marked immature neurons was observed after liraglutide treatment in comparison to saline at 3 months (59%), 6 months (26%), 12 months (57%), and 15 months (61%) of age (p < 0.05) (Parthsarathy and Hölscher, Reference Parthsarathy and Hölscher2013).

This trend was replicated in wild-type mice treated with liraglutide over 37 days, wherein significant increases in cell proliferation in the dentate gyrus were observed in comparison to saline controls at 3 months (20%; p = 0.0457), 6 months (22%; p = 0.0467), 12 months (36%; p = 0.0455), and 15 months (52%; p < 0.05) of age (Parthsarathy & Hölscher, Reference Parthsarathy and Hölscher2013). Similarly, increased proliferation was observed using Ki67 immunostaining post-liraglutide treatment in comparison to saline treatment at 3 months (94%), 6 months (103%), 12 months (143%), and 15 months (122%) of age (Parthsarathy & Hölscher, Reference Parthsarathy and Hölscher2013). Additionally, an increase in DCX-positive neurons post-liraglutide treatment in comparison to saline controls was also observed at 3 months (43%), 6 months (40%), 12 months (74%), and 15 months (68%) of age (p < 0.05) (Parthsarathy & Hölscher, Reference Parthsarathy and Hölscher2013). Notwithstanding, no significant change in gliogenesis was observed in mice treated with liraglutide (p > 0.05) (Parthsarathy & Hölscher, Reference Parthsarathy and Hölscher2013). Results suggest a positive association between liraglutide and neurogenesis, which may be mediated through changes in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.-catenin pathway.

Lixisenatide effect on neurogenesis in animal models

To examine the association between lixisenatide and neurogenesis, we identified two studies (Hunter & Hölscher, Reference Hunter and Hölscher2012; Ren et al., Reference Ren, Xue, Wu, Yang and Wu2021). In an experimental study by Hunter & Hölscher (Reference Hunter and Hölscher2012), mice treated with lixisenatide exhibited an 80% increase in neuronal proliferation marked by BrdU-positive cells in comparison to control (p < 0.01). Additionally, a 70% increase in proliferating neurons was observed in lixisenatide-treated mice in comparison to saline controls observed via DCX analysis (p < 0.05) (Hunter & Hölscher, Reference Hunter and Hölscher2012). Similarly, Ren et al., (Reference Ren, Xue, Wu, Yang and Wu2021) reported that intranasal lixisenatide administration was associated with increased numbers of BrdU and BrdU/DCX-marked cells in the olfactory bulb and hippocampus (p < 0.001). Taken together, these results suggest a positive association between lixisenatide and neurogenesis (Hunter & Hölscher, Reference Hunter and Hölscher2012; Ren et al., Reference Ren, Xue, Wu, Yang and Wu2021).

Semaglutide effect on neurogenesis in animal models

There is insufficient evidence on the effect of semaglutide in neurogenesis. Notwithstanding, a study by Yang et al., (Reference Yang, Feng, Zhang, Li, Wang, Ji, Li and Hölscher2019) reported that mice with middle cerebral artery occlusion administered with semaglutide had a significantly higher number of DCX-positive cells in comparison to saline administration (F = 25.277, p < 0.01) whilst also exhibiting increased expression of neurogenesis markers nestin, CXCR4, and SDF-1 (p < 0.01) (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Feng, Zhang, Li, Wang, Ji, Li and Hölscher2019). Contrastingly, semaglutide administration was also associated with a significant reduction of Iba1-positive cells in the hippocampus in comparison to saline treatment (p < 0.001) (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Feng, Zhang, Li, Wang, Ji, Li and Hölscher2019). Additionally, administration of semaglutide was associated with significant changes in apoptotic pathways (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Feng, Zhang, Li, Wang, Ji, Li and Hölscher2019). Notably, increases in proto-oncogene c-RAF (c-Raf) (p < 0.05), mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 (ERK2) (p < 0.01), B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) (p < 0.05), and decreases in Caspase-3 (p < 0.05) were observed one week after semaglutide administration (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Feng, Zhang, Li, Wang, Ji, Li and Hölscher2019). Although these findings suggest that semaglutide is likely associated with increased levels of neurogenesis, further research is required to investigate changes in specific neuron types.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this systematic review represents the first comprehensive examination of the association between GLP-1s, GLP-1 RAs, and their effects on neurogenesis. Existing literature consistently reports a positive relationship between GLP-1, specific GLP-1 RAs, and neurogenesis, highlighting their potential significance in this domain.

Overall, our results indicate that GLP-1 administration is associated with increased levels of neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus, ganglion cell layer, inner nuclear layer, inner plexiform layer, outer nuclear layer, and the outer plexiform layer. Furthermore, administration of the GLP-1 RAs exenatide, geniposide, liraglutide, lixisenatide, and semaglutide were associated with increased neurogenesis, mainly in the hippocampus and the dentate gyrus. Additionally, changes in neurogenesis exist alongside antiapoptotic and neuroprotective effects (Darsalia et al., Reference Darsalia, Mansouri, Ortsäter, Olverling, Nozadze, Kappe, Iverfeldt, Tracy, Grankvist, Sjöholm and Patrone2012; Sampedro et al., Reference Sampedro, Bogdanov, Ramos, Solà-Adell, Turch, Simó-Servat, Lagunas, Simó and Hernández2019; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Feng, Zhang, Li, Wang, Ji, Li and Hölscher2019). Notwithstanding, increased levels of neurogenesis were also observed in the medial striatum and olfactory bulb, suggesting that GLP-1 RAs may be associated with modulating neurogenesis outside of the hippocampus and dentate gyrus.

Additionally, our results identified that GLP-1 and GLP-1 RA administration are associated with changes in molecular pathways relevant to changes to neurogenesis. Notably, GLP-1 administration was associated with upregulation of GSK3β and Bcl-xL pathways. Similarly, liraglutide was associated with upregulation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, whilst increasing cAMP concentrations in the brain (Hunter & Hölscher, Reference Hunter and Hölscher2012; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Yu, Ping, Xu, Li, Zhang and Li2022). In contradistinction, semaglutide was associated with elevated activation of Bcl-2, c-Raf, and MEK1 pathways, whilst decreasing activity of Caspase-3 (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Feng, Zhang, Li, Wang, Ji, Li and Hölscher2019).-catenin pathway, whilst increasing cAMP concentrations in the brain (Hunter & Hölscher, Reference Hunter and Hölscher2012; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Yu, Ping, Xu, Li, Zhang and Li2022). In contradistinction, semaglutide was associated with elevated activation of Bcl-2, c-Raf, and MEK1 pathways, whilst decreasing activity of Caspase-3 (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Feng, Zhang, Li, Wang, Ji, Li and Hölscher2019).

The effects of GLP-1 RA on neurogenesis may be modulated through changes in signaling pathways. Notably, increased activity GSK3β, Bcl-xL, Bcl-2, Wnt/β-catenin, c-Raf, and MEK1 have been associated with the promotion of neuronal differentiation and proliferation, wherein decreased activity of Caspase-3 has been linked to anti-apoptotic effects (Pimentel et al., Reference Pimentel, Sanz, Varela-Nieto, Rapp, De Pablo and de la Rosa2000; Hur & Zhou, Reference Hur and Zhou2010; Lei et al., Reference Lei, Liu, Zhang, Huang and Sun2012; Fogarty et al., Reference Fogarty, Song, Suppiah, Hasan, Martin, Hogan, Xiong and Vanderluit2016; Aniol et al., Reference Aniol, Tishkina and Gulyaeva2016; Zhang & Liu, Reference Zhang and Liu2002; Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Fernandes-Alnemri, Mayes, Alnemri, Cingolani and Alnemri2017). Additionally, GLP-1 RAs have been noted to exert an anti-inflammatory effect, reducing levels of inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Jin, Hölscher and Li2021). This has been noted to exert a protective effect on dopaminergic neurons (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Jin, Hölscher and Li2021). As such, it could be hypothesised that GLP-1 and GLP-1 RAs subserves neurogenesis through multiple molecular and cellular systems (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Yu, Ping, Xu, Li, Zhang and Li2022; Hunter & Hölscher, Reference Hunter and Hölscher2012; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Feng, Zhang, Li, Wang, Ji, Li and Hölscher2019). Alterations within neuronal development and apoptosis are cellular effects that are observed in mood disorders and neurodegenerative diseases (Martins-Macedo et al., Reference Martins-Macedo, Salgado, Gomes and Pinto2021; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chuang, Lin and Yang2023b). As such, GLP-1 RAs may serve as an effective option in treating neurodegenerative diseases for persons with obesity. By understanding the association between GLP-1 and GLP-1 RAs on neurogenesis, we are able to examine how these agents can facilitate the regeneration of neurons in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and Parkinson’s Disease (PD) (Holst et al., Reference Holst, Burcelin and Nathanson2011).-catenin, c-Raf, and MEK1 have been associated with the promotion of neuronal differentiation and proliferation, wherein decreased activity of Caspase-3 has been linked to anti-apoptotic effects (Pimentel et al., Reference Pimentel, Sanz, Varela-Nieto, Rapp, De Pablo and de la Rosa2000; Hur & Zhou, Reference Hur and Zhou2010; Lei et al., Reference Lei, Liu, Zhang, Huang and Sun2012; Fogarty et al., Reference Fogarty, Song, Suppiah, Hasan, Martin, Hogan, Xiong and Vanderluit2016; Aniol et al., Reference Aniol, Tishkina and Gulyaeva2016; Zhang & Liu, Reference Zhang and Liu2002;, Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Fernandes-Alnemri, Mayes, Alnemri, Cingolani and Alnemri2017). Additionally, GLP-1 RAs have been noted to exert an anti-inflammatory effect, reducing levels of inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Jin, Hölscher and Li2021). This has been noted to exert a protective effect on dopaminergic neurons (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Jin, Hölscher and Li2021). As such, it could be hypothesised that GLP-1 and GLP-1 RAs subserves neurogenesis through multiple molecular and cellular systems (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Yu, Ping, Xu, Li, Zhang and Li2022; Hunter and Hölscher, 2013; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Feng, Zhang, Li, Wang, Ji, Li and Hölscher2019). Alterations within neuronal development and apoptosis are cellular effects that are observed in mood disorders and neurodegenerative diseases (Martins-Macedo et al., Reference Martins-Macedo, Salgado, Gomes and Pinto2021; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Guo and Zhou2023). As such, GLP-1 RAs may serve as an effective option in treating neurodegenerative diseases for persons with obesity. By understanding the association between GLP-1 and GLP-1 RAs on neurogenesis, we are able to examine how these agents can facilitate the regeneration of neurons in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and Parkinson’s Disease (PD) (Holst et al., Reference Holst, Burcelin and Nathanson2011). Although it could be hypothesised that changes in neurogenesis mediated by GLP-1 and GLP-1 RA may provide neuroprotective benefits in AD and PD-related pathogenesis, this hypothesis requires testing (Harkavyi et al., Reference Harkavyi, Abuirmeileh, Lever, Kingsbury, Biggs and Whitton2008; Cao et al., Reference Cao, Rosenblat, Brietzke, Park, Lee, Musial, Pan, Mansur and McIntyre2018; Tai et al., Reference Tai, Liu, Li, Li and Hölscher2018). Notwithstanding, the aforementioned neuroprotective and neuroproliferative effects modulated by GLP-1 RAs highlights the potential of repurposing these agents as an effective option for weight management in individuals with neurodegenerative conditions.

Interpretations and inferences of our systematic review may be affected by methodological limitations. First, our review identified no human studies investigating the association between GLP-1 and GLP-1 RAs on neurogenesis, limiting our ability to extend our findings to humans. Furthermore, assessed animal models vary in species and disease models, which may confound the interpretation of our results. Moreover, GLP-1 RAs vary in structure and bioavailability, which limits our understanding of the extent to which GLP-1 RAs can exert neurogenesis. Notwithstanding, further research vistas should be directed to identifying the association between GLP-1 and GLP-1 RAs on neurogenesis in different neuronal populations, whilst examining the effect of these agents in neurodegenerative diseases such as AD and PD.

Conclusion

Herein, we report a positive association between GLP-1, exenatide, geniposide, liraglutide, lixisenatide, and semaglutide on neurogenesis. These findings provide a summary of the association between GLP-1 and GLP-1 RAs on neurogenesis, and provide a foundation for developing GLP-1 and GLP-1 RAs as potential therapeutic strategies for neurodegenerative diseases.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/neu.2025.4.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding statement

This paper was not funded by any entity.

Competing interests

Dr Roger S. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) and the Milken Institute; speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Neumora Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sage, Biogen, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Viatris, Abbvie, Atai Life Sciences. Dr Roger McIntyre is a CEO of Braxia Scientific Corp. Kayla M. Teopiz has received fees from Braxia Scientific Corp. Dr Joshua D Rosenblat has received research grant support from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR), Physician Services Inc. (PSI) Foundation, Labatt Brain Health Network, Brain and Cognition Discovery Foundation (BCDF), Canadian Cancer Society, Canadian Psychiatric Association, Academic Scholars Award, American Psychiatric Association, American Society of Psychopharmacology, University of Toronto, University Health Network Centre for Mental Health, Joseph M. West Family Memorial Fund and Timeposters Fellowship and industry funding for speaker/consultation/research fees from iGan, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Allergan, Lundbeck, Sunovion, and COMPASS. He is the Chief Medical and Scientific Officer of Braxia Scientific and the medical director of the Canadian Rapid Treatment Centre of Excellence (Braxia Health). Dr Rodrigo B. Mansur has received research grant support from the Canadian Institute of Health Research; Physicians’ Services Incorporated Foundation; the Baszucki Brain Research Fund; and the Academic Scholar Awards, Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto. Hezekiah C.T. Au, Yang Jing Zheng, Gia Han Le, Sabrina Wong, Hartej Gill, Sebastian Badulescu, and Kyle Valentino have no conflicts to declare.