Preface

This Element is the culmination of a long journey of discovery. Ideas from an array of authors across many schools of economic thought are referenced. Novelty is in the way the ideas are synthesised for developing evolutionary price theory. As is appropriate for an evolutionary approach to economics, the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.

I was introduced to anti-trust economics as an undergraduate student by Geoff Shepherd at the University of Michigan. George Stigler strongly prosecuted an opposing view when I was a graduate student at the University of Chicago. Both Shepherd and Stigler mentioned Schumpeter, but neither seriously addressed Schumpeter’s critique of equilibrium economics as being tangential to understanding the process of development under capitalism.

My focus as an early career academic was on empirical research into aspects of competition, including pricing, productivity, profitability, industry structure, and advertising. Increasingly, this research identified phenomena not easily explained by mainstream analysis, such as variance in firm size, large productivity differences among firms producing similar products, rigidity in manufacturing prices in response to fluctuating demand, and a long-term downward trend in the ratio of the prices of primary products to those of manufacturing goods. Initially, I turned to post-Keynesian price theory for explanations, but this theory has a short-run orientation that generally doesn’t address structural change.

My colleagues at the University of Denver in the early 1980s, especially David Levine, introduced me to Josef Steindl’s (Steindl [1952] Reference Steindl1976) analysis of maturity and stagnation in modern capitalism. There are interesting parallels and contrasts between Steindl and Schumpeter in the analysis of competition as a process of differential firm growth following innovations, which I started to explore. However, it wasn’t until 1998 that I presented a paper based on comparing the analysis of competition in Schumpeter and Steindl at the International Schumpeter Society conference in Vienna.

Schumpeter Society conferences provided an ideal forum for developing my ideas about evolutionary price theory. My own presentations generated much constructive feedback, while the presentations of others broadened my understanding of evolutionary analysis. Contacts made at the conferences expanded my network for exchanging ideas and draft papers.

Development of my ideas on evolutionary price theory also benefitted from feedback at presentations to groups beyond evolutionary economics. Presentations to the History of Economic Thought Society of Australia and the Society of Heterodox Economists elicited comments encouraging both clarifications and extensions to incorporate diverse insights. I also benefitted from comments at seminars given at an array of universities and research institutes across the globe.

I owe a special debt of gratitude to co-authors on research containing the nascent ideas forming my approach to evolutionary price theory. Thanks go to Jerry Courvisanos, John Finch, Peter Kriesler, Stan Metcalfe, and David Sapsford. Stan has also commented on drafts of several chapters as well as providing advice and encouragement on the whole project. Curtis Eaton, Peter Earl, and John Foster have read chapters and provided very useful feedback, while Margaret Bloch has cast the editor’s eye over many of the chapters. None of my dear friends who have helped with the development and exposition of my ideas on evolutionary price theory throughout the many years of its development are to blame if I have failed to understand or heed their advice.

1 Introduction

The purpose of this Element is to set out a theory of price determination in capitalist economies that is consistent with the presumptions of evolutionary analysis. First, an open-system ontology is employed as is essential for evolutionary theorising. Second, prices are determined by the interaction of micro, meso, and macro elements. Third, prices change over time in a process characterised by historical specificity and path dependency. The resulting evolutionary price theory deviates substantively in terms of both construction and implications from neoclassical price theory with its closed-system ontology, methodological individualism, and ahistorical epistemology.

Capitalist economies are open systems that evolve through structural change from within, so evolutionary price theory needs to address how prices facilitate and accommodate structural change and how structural change in turn impacts prices. An undue emphasis on ratiocination in neoclassical theory has extracted a high cost, neglecting imagination and creative vitality. With humans questioning and acting creatively to change their circumstances, prices do more than guide the allocation of scarce resources. They provide information used by entrepreneurs and their financiers in evaluating the profitability of innovations. The dual informational role of prices means the information provided to entrepreneurs can disrupt the order created through coordinating the activities of non-innovating buyers and sellers (Bloch and Metcalfe Reference Bloch and Metcalfe2018).

Equilibrium is a closed-system concept that ignores the use of price information by entrepreneurs. Equilibrium according to Schumpeter (Reference Schumpeter1954, p. 969) implies, ‘a set of values of the variables that will have no tendency to vary under the sole influence of the facts included in the relations per se’ [italic in the original]. Reliable information conveyed to entrepreneurs in stable prices combined with their heterogeneous and ever-changing knowledge means such an equilibrium is implausible under capitalism. Schumpeter ([Reference Schumpeter1950] Reference Schumpeter1976, p. 82) clearly recognises this, noting, ‘Capitalism, then, is by nature a form or method of economic change and not only never is but never can be stationary.’

Nelson (Reference Nelson2013) suggests using the concept of market order rather than equilibrium in developing an approach to price theory consistent with the open-system perspective of evolutionary economic theory. Nelson argues that for markets not experiencing disruptive innovations a price theory based on market order has subtle, but important, differences from conventional price theory in the treatment of the behaviour of economic agents (behaviour according to routines replaces optimising behaviour) and the outcome of market interaction (order replaces equilibrium). However, for markets affected by disruptive innovations, ‘neither the standard conceptions of price theory or the more complex notions of market order presented here may have much use in the analysis of what is going on’ (Nelson, Reference Nelson2013, p. 31).

Schumpeter ([Reference Schumpeter1950] Reference Schumpeter1976) characterises markets undergoing disruptive innovation as subject to creative destruction. Creative destruction is a selection process. Innovation adds to variety in the market. Firms whose innovations pass the test of the market are rewarded with high profits, providing the finance required for them to grow relative to established rivals. The products, processes, and routines of the innovators thereby gradually displace those of established firms. Variation, selection, and retention are all parts of the evolutionary dynamic played out in the institutional context of a market economy.

Evolutionary price theory incorporates the evolutionary dynamic by analysing the interaction of heterogeneous firms, including between innovators and established firms, to explain the time path of adjustment in prices and market shares. Discontinuities and path dependence are inevitable in an error-ridden adjustment process, given decisions made on incomplete information and an unknown future. Structural change at the level of the aggregate economy results from the combination of markets experiencing disruption, which usually constitute only a portion of all markets, and the great bulk of orderly markets in which agents operate according to well-established routines.Footnote 1

Fundamental to evolutionary price theory is the micro-meso-macro framework widely used in evolutionary economic analysis (Dopfer et al. Reference Dopfer, Foster and Potts2004). At the micro level, prices change when the behaviour of consumers and firms change, with their creative activity generating new knowledge and passing new information to other agents. At the meso level, differential performance of established and innovative firms leads to differential firm growth in the process of creative destruction, which changes market shares and impacts average prices and the variance of prices over an industry. Prices change at the macro level due to the impact of changes at the micro and meso levels as well as interactions across sectors. There are also influences from monetary and financial institutions. Causation is far from unidirectional.

This Element builds on the incomplete and imperfect sketch of an evolutionary price theory contained in Schumpeter’s writings on capitalist development.Footnote 2 Nelson and Winter (Reference Nelson and Winter1982) and Metcalfe (Reference Metcalfe1998) add essential micro and meso ingredients by analysing the impact on price dynamics from differential firm growth and industry development following on from innovation and firm heterogeneity. Metcalfe (Reference Metcalfe, Shinoya and Nishizawa2008) and Nelson (Reference Nelson2013) argue for replacing Schumpeter’s reliance on the concept of equilibrium with that of order for determining market prices. Bloch (Reference Bloch, Courvisanos, Doughney and Millmow2016b, Reference Bloch2018b) suggests that work on the micro, meso, and macro components of evolutionary price theory can be complemented by incorporating ideas from post-Keynesian theory of administered prices and from Sraffa’s (Reference Sraffa1960) analysis of reproduction prices.

This Element has three parts plus introductory and concluding chapters. Part I deals with economic agents (micro level), Part II with markets and industries (meso level), and Part III with the interactions among industries and with the aggregate economy (macro level). The concluding chapter summarises and points to directions for further research.

Part I begins in Chapter 2 with discussion of individual and household behaviour under conditions of imperfect information, limited cognition, and uncertainty that underpin an evolutionary approach to consumer demand. Following in Chapter 3 is a corresponding discussion of firm behaviour, together with discussion of the need for coordination within the firm of individuals with differing knowledge and information. Routine and habitual behaviour by consumers and the use of rules and routines by firms are central to evolutionary analysis of pricing.

Meso-level analysis in Part II focusses on connections and interactions, between buyers and sellers in markets, and among firms in industries. Chapter 4 considers the balancing supply and demand as the condition for order in markets with undifferentiated products and numerous buyers and sellers, while the use of administered prices and maintenance of excess capacity by firms creates order in markets with heterogeneous products or small numbers of suppliers and buyers. Chapter 5 analyses how differential firm growth among heterogeneous firms producing related products leads to changes in industry structure as well as generating dynamics for product prices.

Part III is devoted to analysis of the aggregate price level. Chapter 6 discusses the relationship between firms and industries in the context of restless knowledge, before examining the transmission of prices across industries through input–output relationships. Schumpeter’s (Reference Schumpeter1939) argument that the business cycle is due to waves of innovations associated with the changing reliability of price information is then considered in Chapter 7, along with the role of monetary and financial institutions. Chapter 8 concludes with a summary and discussion of directions for further development of evolutionary price theory.

Part I Micro

2 Consumers

Bloch and Metcalfe (Reference Bloch, Metcalfe, Chen, Elsner and Pyka2024) observe that the strong rationality postulate underlying much modern economic discourse is increasingly rejected by behavioural economists and complexity theorists (Shiller Reference Shiller2000, Kirman Reference Kirman2011, Arthur Reference Arthur2015). Behaviour is goal directed but calculations need to be made within the confines of limited cognition and present limited knowledge, knowledge that is heterogeneous across individuals and changes by experience and creativity. Bounded rationality and satisficing routines are more reasonable presumptions than optimisation for analysing individual behaviour (Potts Reference Potts2000, Dopfer et al. Reference Dopfer, Foster and Potts2004, Foster Reference Foster2005, Earl Reference Earl2023).

The personal and changing nature of knowledge is widely recognised in the evolutionary analysis of individual and organisational behaviour. Implications for the behaviour of firms have been at the forefront, justifying the replacement of the assumption of optimising behaviour with behaviour according to rules and routines since at least the seminal work of Nelson and Winter (Reference Nelson and Winter1982). There has also been analysis of the implications for markets and institutions (Loasby Reference Loasby1999, Potts Reference Potts2001). In this chapter the focus is on the implications for the evolutionary analysis of consumer decision making and demand.

2.1 Knowing and Acting

Heterogeneity of individuals is recognised in mainstream analysis in terms of differentiated preferences for goods and differentiated skills for workers. This heterogeneity is pointed to as justifying a downward slope to consumer demand for individual products and an upward slope of supply for labour with specialised skills, both contribute to rationalising the stability of equilibrium. However, no heterogeneity is allowed in how individuals make decisions, with every decision being an optimising decision usually based on perfect information or at least rational expectations. Also, whatever heterogeneity of individuals exists is assumed constant for short-run analysis and determined by external influences in long-run analysis.

Imagination is central to the creation of novelty. As Shackle (Reference Shackle1959, p. 753) notes, ‘in a nondeterministic universe where creation of something essentially new can happen from moment to moment, then the individual imagination seems to be the locus, so far as human beings are concerned, of this continual projection of essential novelty into the world process.’ When faced with choice, individuals may respond creatively and act in novel ways.

Human beings are by nature inquisitive and to the extent that they think differently can conjecture different answers to the same question. These different answers transform the state of knowing, such that every solution to a problem has the capacity to define further problems and the growth of human knowing becomes autocatalytic and open. Because individuals know differently, it is not surprising that they behave differently and their behaviour changes over time as their knowledge changes. Loasby (Reference Loasby1999, p. 43) highlights the contribution to economic evolution from heterogeneity and continual change in individual knowledge and behaviour,

What we can reasonably conclude is that the differences between people, partly endogenous, and partly the result of their particular cognitive development, in the patterns of connections by which they make choices or recognise a need for a reconstruction of their strategies for making choices, are primary contributors to the generation of variety and thus to the evolution of economic systems.

Deciding and acting in the presence of uncertainty are problematic in modern economies (Levine Reference Levine1997). The certainties of traditional society have been removed and replaced with an environment subject to the vagaries of restless knowledge. No matter how carefully we develop knowledge, we may be surprised by an unexpected outcome as most action takes place in an environment of at least partial ignorance. Every action generates new information and potentially leads to a change in knowing. Loasby (Reference Loasby1999, p. 149) references Shackle in noting, ‘the incompleteness and dispersion of knowledge are a constant source of opportunities for creating new knowledge; as some ambiguities are resolved, more are revealed, and people are inspired to imagine new ways of closing their cognitive systems’.

The occasional discovery and creative action occur against a background of routinised behaviour. Uncertainty, limited cognition, and imperfect information encourage behaviour according to habits or routines. Hodgson (Reference Hodgson1997) argues habits and rules are ubiquitous in governing individual decisions. Both habits and rules ‘have the form in circumstances X, do Y’, where ‘Rules do not essentially have a self-actuating or autonomic quality but clearly, by repeated application, a rule can become a habit’ (Hodgson Reference Hodgson1997, p. 664).

Habits and rules are in part based on personal experience, so reflect learning from both expected and unexpected experiences (Witt Reference Witt2001). They are also partly based on the social and institutional environment in which the individual operates. The role of institutions and society in formation of habits is at the centre of evolutionary theorising about individual and household behaviour by Veblen (Reference Veblen1899). An individual acts in accordance with their perceived and desired position in society, leading to patterns of consumption that include conspicuous consumption, bandwagon effects, and snob effects.

Individuals are always constrained by rules of the game governing their freedom to act. In a market economy many informal restraints that shape interaction arise in the context of local interactions, local knowledge, and the specific experience of time and place, leading to geographical and historical specificity. Governments set regulations governing the way market interaction occurs (dispute resolution, quality assurance, health and safety matters for example). These regulations often are responses to experiences generated within the system and change over time, coevolving with the activities they are meant to regulate (Dopfer and Potts Reference Dopfer and Potts2008).

Routines are at the centre of the evolutionary approach to decision making. Earl (Reference Earl2023, p. 4) reviews the approaches to decision making in old and new behavioural economics as well as evolutionary economics and suggests, ‘The evolving sets of rules, heuristics, principles and routines that decision-makers use to deal with the challenges of everyday life may be genetically inherited, personally created or outsourced/absorbed from social networks, society in a wider sense and market institutions.’ These sets of decision-making rules are the outcome of a process where, ‘Economic evolution entails the creation of new rules and a competitive selection process whereby the relative populations of different rules (or sets of rules) change, with associated changes in the connective architecture of the economic system and of its subsystems’ (Earl Reference Earl2023, p. 3). This conception of decision making underpins much of the evolutionary approach to consumer demand, which is discussed in the next section.

2.2 Consumer Demand

Early contributions to evolutionary analysis of consumer demand attack neoclassical assumptions of optimising behaviour, especially as applied to new goods. Metcalfe (Reference Metcalfe2001) argues optimisation is neither necessary nor useful in analysing consumer behaviour, suggesting the effects of changes in price and incomes can be well handled by focussing on the time and budget constraints facing consumers in a way that also allows analysis of the demand for new goods. Witt (Reference Witt2001) notes the role of the evolution of consumers wants in explaining the avoidance of satiation despite the enormous growth of personal consumption under modern capitalism.

Despite this early work, Nelson and Consoli (Reference Nelson and Consoli2010) lament the absence of a modern evolutionary theory of household consumption behaviour. They then sketch the outlines of such an evolutionary theory, starting with the requirement that individual rationality is bounded. Households are viewed as engaging in activities to satisfy their wants subject to constraints of income and time, with the degree of success depending on the household’s ability to effectively coordinate its activities. Learning is important to improving this ability, meaning ‘consumption decisions need to be recognized as largely a matter of routine plus marginal changes in routine, except when the household is facing circumstances that are significantly new to it’ (Nelson and Consoli Reference Nelson and Consoli2010, p. 678). Learning is particularly important in the context of new goods and services, ‘the response of households to the availability of new goods and services may involve a significant reorientation of their targets and goals, which in many cases only can be accomplished in the course of learning to do new things’ (Nelson and Consoli Reference Nelson and Consoli2010, p. 681–682).

Chai and Babutsidze (Reference Chai, Babutsidze, Dopfer, Nelson, Potts and Pyka2024) review the substantial body of work that has been done since Nelson and Consoli (Reference Nelson and Consoli2010) to fill gaps in evolutionary consumer theory. Notable advances have occurred, including in the modelling of bounded rationality, understanding the impact of innovation in consumer goods on escaping the satiation trap implied by Engel Curves relating consumption expenditure to income, and the role of social networks in the diffusion of new goods. Chai and Babutsidze (Reference Chai, Babutsidze, Dopfer, Nelson, Potts and Pyka2024, p. 270) conclude, ‘This body of work has contributed to developing a more realistic understanding of i) consumer decision-making, ii) the process of preference formation, iii) the role of consumers in the innovation process, iv) the diffusion of innovations among heterogenous consumers and v) the co-evolution of demand and supply.’

For long-period analysis, treating consumer preferences as exogenous, as in neoclassical theory, is not useful. Consumer preferences are impacted by structural change in the economy as well changes in demographics, culture, and politics. For example, current real wages affect housing status, family formation, and population growth, which in turn affect the future age structure of the population, labour force, output, and consumer demand.Footnote 3

Consumer demand needs to be considered as part of the coevolutionary process involving the economy and all other aspects of society, including the process of change in economic, cultural, educational, and political institutions (Dopfer and Potts Reference Dopfer and Potts2008, Almudi et al. Reference Almudi and Fatas-Villafranca2021). Potts (Reference Potts2017) points to the coevolution of institutions and consumer demand in explaining why Keynes (Reference Keynes1930) was so wildly wrong in his prediction regarding the expansion in leisure that would accompany growth in productive capacity over time. Potts argues Keynes ignored innovation under capitalism is endogenous and is oriented towards generating profit, which means a bias towards encouraging production and consumption of new goods over pure leisure. Expanding production under capitalism cannot solve the economic problem of scarcity because creating markets (and the preferences underlying demand) attracts the attention of entrepreneurs.

Time is required for novel products to build up a substantial market. Earl (Reference Earl2022, Chapter 11.7) refers to the uptake of novel products as following a meso trajectory, with the number of users of a novel product increasing over time along an S-shaped curve. In the origination phase, the novel product attracts a niche market of pioneering buyers who have a particular interest in the distinguishing features of the novel product, and who learn about the product through their social networks or other specialist sources. Initially, the product is often expensive relative to available alternatives, and to its own future price, due to high start-up production cost.

Earl (Reference Earl2022, Chapter 11.9) cites several barriers to the rapid adoption of new technology, including the high initial cost to the consumer, the uncertainty regarding the success of competing standards for the new technology (as in Betamax versus VHS for video players), and limited availability of complementary products (as in the limited proportion of all music available on CDs). As prices of the new technology fall, technological standards are clarified, and availability of complements expands as more consumers are attracted. Eventually, new lifestyles evolve incorporating the novel product, as has been the case of with household appliances, including washing machines, dishwashers, and air conditioners. Suburban lifestyles based on the automobile with shopping centres and long distances to work provide an excellent example of the coevolution of novel products and institutions.

When novel products reach the maturity phase of the meso trajectory, they have been acquired by very large proportions of the target population. In the case of durable products, new sales depend on replacement demand. Marketing efforts switch to convincing consumers to replace their current model with something new and better, while for nondurables the effort is on increasing the quantity consumed by each consumer. Saturation of the market limits the growth of demand, with the novel product having reached the top of the S-shaped diffusion curve.

Where does the discussion of this section leave an evolutionary theory of consumer demand? The mainstream assumption of unlimited calculation ability and perfect information are clearly rejected. The notion that buyers always can identify and transact at the best available offer is unviable. Their purchases are subject to the incomplete distribution of information on prices and product availability, introducing a stochastic element into the amount bought at any price. Yet, as Nelson and Consoli (Reference Nelson and Consoli2010, p. 679) point out, ‘the “demand curves” described here are capable of doing many of the same jobs as the demand curves depicted and rationalized in neoclassical theory.’

Differences between the ‘demand curves’ of evolutionary theory and those of neoclassical theory are generally a matter of degree, at least for goods and services for which consumers have established routines. Constraints on information and decision-making ability encourage reliance on habits and routines that lead to inertia in consumer behaviour. Consequences include limited response to changes in income and prices as compared to optimising behaviour, especially in the very short run. Hence, the short-run price elasticity of demand for mature consumer goods and services is likely to be low. Likewise, the short-run marginal propensity to consume out of income is expected to be below the corresponding average propensity. Over time, greater adjustment occurs, better understood as a lagged response than a higher long-run elasticity, as path dependency means adjustments continue even if the price or income change is reversed.

Foster (Reference Foster2021) uses the evolutionary approach outlined earlier to develop a model of aggregate consumption building on the Keynesian approach of Dusenberry (Reference Duesenberry1949). Aggregate consumption has two components. The first component ‘is determined by a precommitment to a particular set of interconnected behavioural rules, ranging from meso-rules that are broad and cultural, down to personal commitments to individual routines and habits that are influenced by targeted advertising and marketing’ (Foster Reference Foster2021, p. 783). This component accounts for the bulk of consumption expenditure and is heavily path dependent, so current aggregate consumption depends heavily on past consumption. The second component consists of purchases of novel goods and services and follows a diffusion process as awareness and interest in these novelties spread through networks. Diffusion builds the impact of expanding connections into aggregate consumption through networks of individuals, with limits set by the size of the relevant population.

Foster estimates parameters of the model with data from the US economy from 1972 to 2018. The results are consistent with the hypothesised relationship and suggest a gradually waning impact of consumerism, which is the dominant meso-rule stimulating consumer demand for novelties since the middle of the twentieth century. As a result, the impact of fiscal policy on growth is weaker than in earlier decades and greater expansions of money or budget-financed credit are required to keep unemployment low.

2.3 Conclusions

The mainstream characterisation of the representative consumer maximising utility with exogenously determined preferences is unhelpful, even destructive to understanding economic evolution. Individuals are heterogeneous, with differentiated knowledge, cultures, and experiences. They have imperfect information and limited cognition, which leads to reliance on habits and routines in decision-making. They are also occasionally creative, especially in dealing with disappointed expectations, novel circumstances, and new products.

Consumer demand reflects the use of routines and habits to deal with imperfect information and limited cognition in a changing and uncertain environment. Demand takes time to adjust to changes in price or income, while demand for new products depends on diffusion of interest through networks of individuals. Evolutionary analysis resolves the satiation problem, as demand coevolves with the supply of novel products in an unending process moulded by institutional frameworks and social networks.

3 Firms

Optimisation is rejected as a principle governing decision making at firms in critiques of the mainstream theory of the firm by Cyert and March (Reference Cyert and March1963), Simon (Reference Simon1964), and Shackle (Reference Shackle1970). For evolutionary analysis, optimisation is inconsistent with emergence and complexity, which are fundamental properties of an evolving economy. In a review of theories and empirics on firm growth, Coad (Reference Coad2009, p. 8) argues, contrary to neoclassical economics, ‘firms are not rational, many fail, and that many miss opportunities. Furthermore, many firms may shape their own destinies, as it were, and make opportunities for themselves that did not seem to exist before.’ For purposes of evolutionary price theory, firm behaviour is assumed to be governed by rules and routines developed over the unique historical experience the firm, which reflects the connections among individuals with specialised knowledge internal and external to the firm.

Mainstream economics treats all firms operating within an industry as identical. No other outcome is logically possible given the assumptions of universally optimising behaviour with perfect information and equal access to technology and markets. Winter (Reference Winter2006) points out history, dynamics, and probability combine to ensure firms differ. Firms exist in the modern economy in a bewildering variety of sizes, scope of operations, forms of governance, and orientations.

For purposes of developing an evolutionary price theory, three aspects of the differences among firms are discussed. First are the related characteristics of the size, scope, and organisation of the firm, with small, large and mega-firms distinguished. Second, different goal orientations of firms are surveyed, with profit, growth, and innovation discussed. Finally, the relation between the firm and the market is considered, distinguishing between price-taker and price-maker firms. The chapter closes with an illustration of application of evolutionary price theory for the case of a novel product that has no close competitors. Price theory for markets with multiple sellers is presented in subsequent chapters, orderly markets in Chapter 4, and disrupted markets in Chapter 5.Footnote 4

3.1 Firm Size, Scope, and Organisation

A better understanding of the variety of behaviour across firms can be achieved by distinguishing categories of firms according to size, scope, and organisation. Firm size is important as only larger firms can internally reap full advantages of specialisation from the division of labour. However, specialisation within the firm poses challenges of coordination and resistance to innovation. These challenges increase with the scope of firm activities, but increased scope offers opportunities for diversification and synergy, especially in relation to innovation through new products, processes, and markets.

3.1.1 Small Firms

Most firms are small in terms of sales and employment, privately owned, and produce a limited range of products serving a narrow range of customer needs. The traditional terminology of family-owned firm fits well in conveying that the cognition and communication issues for these firms overlap those facing individuals and households discussed in the last chapter. However, the production activity of the small firm tends to be highly specialised to take advantage of the gains from specialised expertise. Specialisation combines with idiosyncratic skills, experience, and information of owners to ensure there is substantial variety in performance among the group of small firms producing any commodity. Small firms dominate parts of the supply of personal services (hair salons and massage parlours) as well as household services (electricians and plumbers). They have dominated many retail businesses, such as groceries, bakeries, restaurants, and hotels, but these businesses are increasingly dominated by chain or franchise operations. They have also dominated agricultural production, and still do in many parts of the world.

Marshall (Reference Marshall1920, p. 263–264) suggests the growth of the family-owned firm is limited by the vitality of its founder, ‘Nature still presses on the private business by limiting the life of its original founders, and by limiting even more narrowly that part of their lives in which their faculties retain full vigour.’ He then uses the analogy of trees in a forest to discuss the diverse experience of growing and declining firms producing a commodity, suggesting the need to focus on a representative firm when analysing activity for the whole industry.

Activity of the small firm is not only limited by the life span and vitality of the founder. Personal wealth typically places a constraint on the size of the family-owned firm, much as income places a constraint on the consumption of the household (Steindl Reference Steindl1945). Borrowing is possible but only in amounts limited by Kalecki’s (Reference Kalecki1937) principle of increasing risk. Also, as noted in the last chapter, the knowledge and skill of individuals are generally limited, meaning the scope of activity in which the small firm is competitive is restricted. Adding employees to successfully provide for expansion requires additional skills in management. Not surprisingly, most firms remain small even if they manage to survive more than a few years.

Profit is a typical objective of the small firm, as the income of the owner depends on it. Survival is also front of mind, with minimal buffers available to deal with unexpected shocks and limited access to external finance. If the firm is successful and generates unexpected profits, there is a tendency to reinvest these profits in the same activities given that the financial constraint to expansion has been relaxed and the market has responded favourably to the firm.

3.1.2 Large Firms

Among the few firms that discover longevity, a very small number grow to a large size and scope. Size and scope challenge the capabilities of a family-owned firm, leading to institutional change. Recognition of the development of a different species of firm is certainly not new, with roots at least as far back as Marshall’s (Reference Marshall1920) treatment of joint-stock companies. Such companies were common in undertaking large projects, such as building canals and railways in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. By the early twentieth century large enterprises had come to dominate large swathes of industry in the United States and Europe. For example, Ford Motors in automobiles, US Steel in steel making, and Standard Oil in petroleum refining.

The distinctive organisational and behavioural characteristics of modern large corporations are discussed in The Modern Corporation and Private Property (Berle and Means Reference Berle and Means1932). Subsequent theoretical contributions build on the separation of ownership and control identified by Berle and Means. Managerial objectives, other than profit maximisation, are identified as drivers of decision making by Baumol (Reference Baumol1958), Marris (Reference Marris1964), Wood (Reference Wood1975), and Eichner (Reference Eichner1976).

Large organisations can benefit from specialisation, with individuals developing expertise in dealing with small sets of tasks. However, to function effectively, separate individuals, teams and departments within the organisation must coordinate their specialised knowledge. Development of methods for ensuring internal coordination is itself a specialised task and the subject of specialised study since, at least the work of Taylor (Reference Taylor1911), Marshall (Reference Marshall1923, especially Chapter 11), and Barnard (Reference Barnard1966 [Reference Barnard1938]).

Knowledge is a state of the individual mind. A large firm depends on a degree of correlation of the knowledge of team members, that they understand their tasks in common, that when asked a question or confronted by a command they act in very similar, typically indistinguishable, ways. Correlated behaviour is routinised behaviour, reliable behaviour that is confidently shared. The degree of sharing is highly uneven, depending on the context. At one level it may involve knowledge shared with very few others, but by degrees of generalisation we find kinds of knowing shared across the business department or the whole firm, albeit at a conceptual rather than practical level.

How is the necessary correlation of knowledge in large firms brought about? Knowledge is a state of mind that is necessarily inseparable from the person who knows. Information, by contrast, is an expression in some form of what the individual knows, it is not knowledge per se, but rather a particular representation of that knowing. Information is a public representation of private knowing, so information is inherently incomplete. Direct communication between employees allows communication going beyond codified information. The large firm has a distinct advantage as information and communication requirements can be economised through appropriately designed organisational structure (Arrow Reference Arrow1974).

Firms differ because each employee imagines differently, and because the interaction and coordination between employees is organised differently. What employees imagine differs because they are different individuals, bringing different expertise and experience to understand phenomena and to develop their understandings. The firm’s unique manner of organisation further differentiates the learning process because of differences in the manner of learning across firms. New imaginings are constantly being added and diffused within the firm, whereas old imaginings are forgotten or even rejected. Without such dynamics of individual knowledge within the firm it is impossible for the firm to change endogenously, impossible to conceive of innovation, which necessarily differentiates firms.

Mainstream theory of the firm assumes given technology, products and market demand and factor supply conditions that constrain behaviour. Optimisation under these constraints is then imposed for analysing the comparative statics of the impact of exogenous changes in technology and factor supply conditions. No consideration is given to how firms might develop from within, how they develop endogenously and deliberatively.Footnote 5

3.1.3 Mega-firms

An organisational development in large firms is the emergence of mega-firms discussed by Bloch and Metcalfe (Reference Bloch, Metcalfe, Pyka and Foster2015). Mega-firms constitute a sub-species of large firms, which are particularly well suited to dealing with the evolutionary context of the modern economy. In Bloch and Metcalfe emphasis is placed on the role of the internal structure and external linkages of mega-firms in the innovation process, shifting focus from the market as a selection mechanism that features in much neo-Schumpeterian literature. Mega-firms have considerable protection from markets, including capital markets, through their large size and scope, which provides them with the ability to internally generate and allocate resources for growth, diversification, and innovation. An early example of a mega-firm is General Electric that diversified from light globes to electronic equipment to jet engines and the financing thereof. A more recent example, Amazon has moved from online book sales to a generalised online marketplace as well as cloud computing services.

Mega-firms are complex organisational systems, produce many goods or services, often in different geographical locations, sell in different kinds of markets to customers who put their goods and services to different uses, and purchase many kinds of input to support their production activities. Employees of the firm are individually knowledgeable, but their knowledge is highly circumscribed and pertinent to a narrow aspect of the firm’s functioning. They are ignorant with respect to the totality of knowledge deployed by the mega-firm. Winter (Reference Winter2006, p. 135) identifies the fundamental difficulty facing such firms in question-and-answer format,

Does anybody in the large firm know what’s going on? Answer: No. Any single individual’s conceptual understanding of the firm in its entirety is mainly at an extremely abstract and aggregative level. Knowledge representing many lifetimes of education, training and experience is represented in such a conceptual picture by a few names of occupations and organizational subunits.

How the mega-firm operates then depends on how pools of localised knowledge are connected. Shared understanding among individuals with specialised knowledge contributes to the cohesion, and hence, stability of the mega-firm. However, shared understanding is undermined by the ongoing learning in separate parts of the organisation. A tension exists between the standardisation of practices into routines that underpin the shared understanding and efficiency of the mega-firm and the quite different practices required for change. Leadership in the form of entrepreneurship is required to overcome this tension, so the mega-firm is an entrepreneurial firm.

Mega-firms have a competitive advantage from the extensive capabilities and specialised knowledge of large numbers of individuals, which allows them to reap dynamic economies through the coordination of a division of labour. Importantly, mega-firm capabilities expand organically from the interaction of the knowledge of individuals, enhanced by introspection and creative problem solving, which provides some protection for the firm against the ravages of creative destruction in the competitive process. To put this in the language of business strategy, mega-firms are organised to achieve sustainable competitive advantage (Porter Reference Porter1985).

3.2 Orientations of Firms

Evolutionary economics is history friendly. Path dependency, historical events, and individual personalities feature prominently in the accounts of the development of individual firms and industries (Chandler Reference Chandler1962 and Reference Chandler1977, Malerba et al. Reference Malerba, Nelson, Orsenigo and Winter1999, Dopfer Reference Dopfer, Foster and Metcalfe2001). The observed variety of firms in the economy reflects the importance of their separate experiences. It also reflects the different ways in which firms interact with their environment. In this section, four orientations of firms are discussed, survival, profit, growth, and innovation. A firm may have multiple orientations, which are often complementary as noted at points in the discussion next.

3.2.1 Survival

Survival is a precondition to the pursuit of any other objective by a firm. Mainstream economics with its assumptions of perfect information and rational expectations ignores the early death experienced by most firms. When the environment is only partially known and continually changing in unexpected ways, mistakes are made and often fatal. Unrealistic assessments of firm capabilities are also common. A firm’s life is typically precarious and short.

Firms can act to reduce exposure to risk. For example, reducing borrowing and other long-run financial commitments means a lower probability that a future unexpected downturn in revenues or increase in costs leave the firm exposed to insolvency. However, hazards associated with uncertainty, the unknowable aspects of the future in an evolving economy, are unavoidable (Knight [Reference Knight1921] Reference Knight1971).

Choosing a strategy to achieve survival in an evolving economy is not straightforward. A strategy of sticking with established routines is not foolproof. Witness the fate of established firms who don’t imitate or innovate when faced with Schumpeter’s perennial gale of creative destruction. Survival requires alertness to changes in economic environment and appropriate responses. There is no guarantee of success, but it is reasonable to expect firms with a survival orientation to be over-represented in the population of surviving firms.

3.2.2 Profit

Profit maximisation is not a realistic objective, but an orientation towards profit has benefits for firms. Profit is the source of personal wealth for family-owned firms. Profit is positively linked to share price for publicly traded corporations, which impacts performance appraisal and bonuses of managers as well as on the value of their share options.

As well as being directly desirable, profit can be the means to an end. The connection between profit and survival is clear when unpredictable shocks are an unavoidable part of doing business. Profit also is important in the pursuit of growth or innovation.

In mainstream analysis of a world of perfect information and rational expectations, financing growth of production capacity or research and development activities aimed at innovation is straightforward. Determining the profits from investments in growth or innovation is simply a matter of calculation, available to a firm and to its financial backers. However, as explained in Section 5.1.2, the situation is radically different in an evolving economy with incomplete information, limited cognition, and an unknowable future. Realised profits enable risky investments in growth and innovation by providing a market test of success for potential backers as well as a direct means of finance.

3.2.3 Growth

Growth features as an objective for firm behaviour in some mainstream and post-Keynesian theory of the firm as discussed in the section earlier. A preference for growth over profit is linked to the separation of managerial control from ownership. Managers benefit from overseeing larger operations in terms of power, prestige, and salary. Growth and large size also help protect managers against losing control through merger or acquisition.

From an evolutionary perspective, growth is an obvious orientation to attribute to firms. Metcalfe (Reference Metcalfe1998, p. 29) suggests, ‘an evolutionary process explains how population structures change over time, and how structure is an emergent property.’ Under capitalism, innovations are spread in good part through the relative growth of innovating firms. Faster growth of innovating firms than their non-innovating rivals diffuses the innovation, increasing the share of output carrying the innovation. An orientation towards growth for innovating firms thus facilitates the evolutionary process.

3.2.4 Innovation

Schumpeter (Reference Schumpeter1961 [Reference Schumpeter1934]) assigns a special role, entrepreneurship, to the initiator of innovation and associates this role with the founding of new firms. These firms are small and individually controlled. While he later shifts focus to the role of large industrial firms as sources of innovation (Schumpeter Reference Schumpeter1976 [Reference Schumpeter1950]), observation suggests small firms remain prominent as sources of innovation in modern economies (Acs and Audretsch Reference Acs and Audretsch1988).

Schumpeter points to the need for leadership to overcome resistance to change and divert means of production from established activities to new uses. Overcoming resistance to change for a small firm generally involves resistance in the external environment. If obtaining means of production requires finance beyond the personal wealth of the owner or immediate family, banks or other external backers need to be convinced of the merits of the innovation. Only few small firms are likely to be led by individuals with the requisite skills.

For the large firm, resistance is likely to be within the organisation. Large firms may reallocate means of production from other activities or use existing lines of finance, but only when the competing interests within the firm can be overcome and the directors are convinced that the innovation has merit. Innovation is problematic in large firms because of the tension between the routines that underpin the efficiency of the firm and the different routines required for change. The former depends upon shared understanding within the firm as to its routines, whereas the latter depends on challenging and breaking the rigidity associated with the pursuit of efficiency. The former is the domain of management in a narrow sense, while the latter is the domain of entrepreneurial imagination, of thinking through how the firm could be different with respect to activity and organisation. Some, but not all, large firms are organised to overcome internal resistance and develop an orientation towards innovation.

The mega-firm with its large size and scope is well suited to resolve the tension between efficiency and innovation by devoting efforts to the integration of new knowledge within the firm. These efforts mean the mega-firm can use its existing capabilities to be able to innovate and to adapt to changing external conditions. Innovation based on connecting knowledge of individuals within a large and complex organisation can point in radically new directions, if supported by the firm’s leadership. Thus, the mega-firm fits well with Eliasson’s (Reference Eliasson, Dopfer, Nelson, Potts and Pyka2024) depiction of the experimentally organised decision team that not only innovates but often operates at the meso level creating new products, processes and, even, new markets, so it is unlikely to be fully identified with only one industry or sector of a single economy, at least not indefinitely.

Innovating firms are problematic for mainstream economic analysis. The explanation of firm behaviour in terms of optimisation subject to constraints is undermined by the self-transforming nature of the innovating firm, which weakens external constraints of technology, resources, and preferences. Optimisation is a dubious assumption for explaining behaviour of any firm in an evolving economy with imperfect information, incomplete networks, and fundamental uncertainty about the future.

Even evolutionary economic analysis is challenged by innovating firms. The boundaries of firms, market and industries are under continual challenge by innovation (Bloch and Finch Reference Bloch and Finch2010). However, for analytical purposes it is sometimes useful to associate firms with a particular product, a group of products with a market, or a group of firms with an industry. Examples include the analysis of price as a coordinating mechanism for buyers and sellers in a market (Chapter 4), and the analysis price dynamics as emerging from the selection process among the population of firms in an industry (Chapter 5). Detailed discussion of broader implications for evolutionary price theory of self-transformation by firms is postponed to Chapter 6.

3.3 Pricing Behaviour

Mainstream economics portrays competition as a structural characteristic of markets determined by the number and relative size of buyers and sellers. This is highly misleading, ignoring the roles of technology, institutions, and history in determining patterns of competition. Small firms often operate in a niche market with limited competition, such as the local bakery or a highly specialised professional service provider. Also, very large firms operating in markets for standardised commodities often have very limited control over the current market price of their product, with examples including firms buying and selling commodities like wheat or coal on world markets.

All firms in an evolving economy regardless of size, scope, and organisation face an environment characterised by imperfect information and uncertainty. They also generally operate with a limited number of direct competitors. Crucially, the historical and institutional characteristics of the market are critical in creating the competitive conditions faced by a firm, more so than the number or size distribution of firms emphasised in mainstream economics. Nonetheless, the distinction between price-taker and price-maker firms that features in mainstream theory of perfect and imperfect competition can be usefully adapted to evolutionary price theory.

3.3.1 Price-Taker Firms

Some firms enter the market with a minimum acceptable price and a willingness to sell up to a maximum quantity at or above that price, perhaps with a willingness to expand the quantity sold at higher prices. I categorise these firms in the extreme case as price takers. Though they need not face a horizontal demand curve for their products as in neoclassical price theory, an essential behavioural characteristic is that they don’t adjust the quantity supplied to market with the aim of influencing the market price.

In the evolutionary version of price-taker behaviour, firms adapt to the market rather than control it. Nelson (Reference Nelson2013) uses this characterisation in discussing how conventional supply and demand analysis can be adapted for evolutionary analysis. Being able to specify minimum price and maximum quantity combinations for each individual buyer or seller, without reference to offers and bids from other market participants, means the quantity bid for or offered at any price can be added together to obtain a market demand or supply curve, respectively. Nelson argues the appropriate balancing concept from an evolutionary perspective is market order rather than market equilibrium. Determination of price in orderly markets is explored in detail in the next chapter.

Institutions and history matter crucially in creating market conditions favourable to price-taker behaviour. Organised commodity markets, such as the Chicago Board of Trade and the London Metals Exchange, are institutional exemplars. Rules and regulations developed over time facilitate the determination of a price balancing bids and offers for a specific variety of commodity at a specified place and word quality. For current and, often, multiple future delivery dates. Historical discounts and premiums then guide price determination for related varieties for other places and word, qualities.

Organised national or international exchanges exist for many of the most important metal and storable agricultural commodities. Perishable agricultural commodities tend to be traded on local auction markets, although government intervention to control marketing is not uncommon. In general, historical development or government design has created market conditions where individual producers of primary commodities are price takers, even when collectively operating as price makers, such as with local marketing boards or, most notably, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries.

Kalecki (Reference Kalecki1971) examines price formation in modern capitalist economies by associating price-taker behaviour with firms operating in primary production, while manufacturing firms using primary products as raw materials engage in price-maker behaviour. The dichotomy in pricing behaviour means the ratio of the price of raw materials to the price of manufactured goods moves in the same direction as the rate of growth of output over the business cycle. This dichotomy is applied in Chapter 7 to examining the impact of waves of innovation on the price system and the price level.

3.3.2 Price-Maker Firms

Price-maker firms use rules or routines to set a fixed price for each of their products and offer all their available supply at those prices. Prices set by these firms are indirectly impacted by influences of buyer demand for the products or the pricing behaviour of firms selling substitute products. The indirect impact on rules and routines used in pricing is explained in the remainder of this section.Footnote 6

Bloch (Reference Bloch2018b) suggests using post-Keynesian pricing rules in developing micro-level analysis for an evolutionary theory of price determination. Post-Keynesian pricing rules are designed to capture the behavioural routines used by firms possessing market power, especially firms that dominate manufacturing in the modern economy. Large and complex enterprises need behavioural routines that can be applied across the organisation and monitored centrally. Importantly, post-Keynesian pricing rules share the presumptions of evolutionary analysis, namely imperfect information, distributed knowledge, open systems, and development from within.

A general characterisation of post-Keynesian pricing rules is that firms set price equal to a measure of normal unit cost multiplied by the firm’s desired price-cost ratio (Lee Reference Lee1999, Bloch Reference Bloch, Courvisanos, Doughney and Millmow2016b). Normal unit cost is the level of cost when the firm operates at its expected level of capacity utilisation, which is generally well below maximum possible production. Excess capacity provides a buffer for supplying unexpected increases in demand and a strategic deterrent against existing and potential rivals. In some post-Keynesian pricing rules, the measure of unit cost covers the normal full cost of production, including overheads and an allowance for the depreciation of fixed capital. In other variants only labour, raw materials, and intermediate inputs used in current production are included, providing a measure of normal average variable cost. A feature common to all variants is that the measure of normal unit cost doesn’t change as output fluctuates in the short period.

Various explanations are given regarding how the price-cost ratio desired by firms is determined. The full-cost pricing rule of Hall and Hitch (Reference Hall and Hitch1939) emphasises dealing with uncertainty and maintaining long-run sustainability. Monopoly power features prominently in the theoretical work of Kalecki (Reference Kalecki1971) on mark-up pricing, with the concept of monopoly power extending beyond the market structure notion of neoclassical economics (Kreisler Reference Kriesler1987). Requirements for internal financing of firm investment in extra capacity feature in the work of Eichner (Reference Eichner1976), Harcourt and Kenyon (Reference Harcourt and Kenyon1976), and Wood (Reference Wood1975). Steindl (Reference Steindl1976) and Sylos-Labini (Reference Sylos-Labini1962) emphasise the rate of growth of industry demand as well as conditions of entry and exit for the industry in which the firm operates.

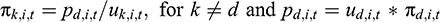

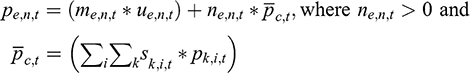

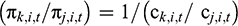

A general form of post-Keynesian pricing rules has normal unit cost and the desired price-cost ratio as the proximate determinants of the administered price set by price-maker firms in the short period. The price for the kth firm operating in the ith industry at time t,

![]() , is given by the firm’s normal unit cost,

, is given by the firm’s normal unit cost,

![]() , multiplied by the desired price-cost ratio,

, multiplied by the desired price-cost ratio,

![]() ,

,

Fluctuations in output due to rising or falling demand have no immediate impact on the desired price-cost ratio or normal unit cost, so the short-period price is unaffected by demand fluctuations. In contrast, changes in prices for intermediate inputs and labour, unless temporary and expected to be reversed, lead to changes in normal unit cost and proportional changes in product price to maintain the desired price-cost ratio.

Key questions in applying post-Keynesian pricing rules to an evolutionary context are what determine the values of normal unit cost and the desired price-cost ratio both at a point in time and in terms of movement over time. Bloch (Reference Bloch, Courvisanos, Doughney and Millmow2016b) addresses these questions in the context of providing a Schumpeterian twist to post-Keynesian price theory. Key issues identified there are whether the costs of overhead and depreciation are included in the unit cost measure or in the desired price-cost ratio, the role of market structure in determination of the desired price-cost ratio, the impact of creative destruction on the dynamics of industry-average values of normal unit cost and desired price-cost ratio, and how obsolescence and R&D costs are handled. These issues are discussed at various points in the following chapters.

3.3.3 Price Leadership

Price-taker and price-maker firms can coexist in the same market. Indeed, models of price leadership presume such coexistence. In the simplest case of price leadership, firms produce virtually identical products and prices for all firms are equal. A single dominant firm, the leader, is the price maker and other firms, followers, act as price takers. Heterogeneity in normal unit cost across firms is accommodated through compensating differentials in price-cost ratios. The price-cost ratio for each of the price-follower firms is determined by its own normal unit cost and the price set by the leading firm, firm d,

(3.2)

(3.2)

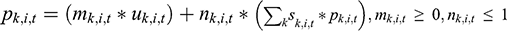

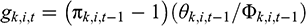

Price leadership is an extreme case of interdependence of pricing rules across firms producing similar products. Kalecki (Reference Kalecki1971, Chapter 5) proposes a pricing rule with a firm’s price as a linear function of its own normal unit cost and the average price of related products,

(3.3)

(3.3)

The last term on the right-hand-side of Equation (3.3) is the weighted average price of all firms producing similar products, with

![]() being the share of industry sales accounted for by the kth firm. A greater weight on own cost suggests greater independence in pricing and a greater weight on average price suggests greater interdependence. In the limiting case of price leadership,

being the share of industry sales accounted for by the kth firm. A greater weight on own cost suggests greater independence in pricing and a greater weight on average price suggests greater interdependence. In the limiting case of price leadership,

![]() > 1 and

> 1 and

![]() = 0 for the price leader, while

= 0 for the price leader, while

![]() = 0 and

= 0 and

![]() = 1 for price followers (Asimakopoulos Reference Asimakopoulos1975, Bloch Reference Bloch1990).

= 1 for price followers (Asimakopoulos Reference Asimakopoulos1975, Bloch Reference Bloch1990).

The firm’s price increases with both the

![]() and

and

![]() coefficients, given levels of its own unit cost and the average price of similar products. These pricing coefficients can vary over firms, with the price leadership case being an extreme example. The average price across all firms is given by,

coefficients, given levels of its own unit cost and the average price of similar products. These pricing coefficients can vary over firms, with the price leadership case being an extreme example. The average price across all firms is given by,

(3.4)

(3.4)

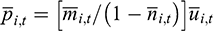

where a bar over a variable or coefficient indicates it is an appropriately weighted average over the group of products as with average price in the last term of (3.3). Kalecki (Reference Kalecki1971, Chapter 5) refers to the term

![]() as the degree of monopoly for the industry consisting of the group of producers. The degree of monopoly is influenced by a range of factors, including industry concentration, the degree of sales promotion, overhead costs as a proportion of total costs, and the strength of trade unions.Footnote 7

as the degree of monopoly for the industry consisting of the group of producers. The degree of monopoly is influenced by a range of factors, including industry concentration, the degree of sales promotion, overhead costs as a proportion of total costs, and the strength of trade unions.Footnote 7

The expressions in (3.3) and (3.4) are useful in evolutionary price theory because they connect individual firm price setting to the firm’s own normal unit cost and the average price in the industry. Innovation by a single firm impacts its cost and price, which then flows through to the prices of other firms in the industry. Average price for the industry is determined by the averages of pricing coefficients and unit cost across all the firms in the industry, which means that average price changes with the distribution of market shares as well as changes in pricing coefficients and normal unit cost at individual firms. Changing structure of market shares due to differential firm growth is at the centre of analysing price dynamics for markets disrupted by innovation in Chapter 5.

3.3.4 Pricing of Novel Products

Novel products are central to the evolutionary process. Distinctive new products feature prominently in consumer expenditures over the modern era, products such as computers and mobile phones most recently, adding to televisions and air conditioners for the previous generation, automobiles and radios for the generation before, and the even earlier mass production of textiles, clothing, and footwear. Such products have been essential in maintaining consumption as a share of household income despite rising real incomes noted by Foster (Reference Foster2021) as discussed in Chapter 2.

Novel producer products have been essential for transforming production processes. Mechanised assembly lines, electrification, computers, and robots are among the array of novel products raising labour productivity and lowering manufacturing costs. Railroads, trucks, planes, and fossil-fuel powered ships have connected manufacturers to cheaper sources of raw materials and intermediate products. In primary production, costs have been dramatically reduced and output increased using novel products such as tractors, synthetic fertilisers, seismic mapping, dredge lines, computers, and drones.

Pricing of novel products is complicated. The producer faces great uncertainty regarding buyer reaction and the cost of production over the full meso trajectory of origination, adoption and retention for the product as discussed in Chapter 2. Mainstream economics ignores the issue. Novelty is inconsistent with the certainty presumed in perfectly competitive equilibrium.

Pricing analysis discussed in previous sections is compatible with novel products, but a nuanced and multi-phase application is required. Nuance is required in combining elements of the analysis of price takers, price makers, and price leadership. Further, separate analyses are required for each phase of the meso trajectory of origination, adoption, and retention of the novel product.

Initially, the producer of the novel product is a price maker without close competitors, but its circumstances differ from those of an established seller who is a monopolist. In particular, the producer of the novel product can take the prices of its distant competitors as given because it looms small as a threat when its product is first introduced. In this sense, the firm starts in a situation with somewhat like a follower firm under conditions of price leadership.

In its situation as a price follower, the prices of established products provide benchmarks for the producer of the novel product. For consumer goods, the buyer needs to fit the novel product into the established pattern of expenditure. Comparisons to existing products that satisfy related wants are inevitable, with price as well as product characteristics evaluated in terms of value for money. For producer goods, the novel product is attractive when the downstream producer can lower its production cost. The price of currently purchased producer goods determines the comparison cost.

Pricing novel products using an adapted version of Kalecki’s model of price-setting equation, (3.3), includes a benchmarking role for prices of established firms. The price of the novel product of an entrepreneurial firm, e, that starts a new industry, n, is given by,

(3.5)

(3.5)

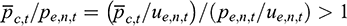

Weights used in calculating the average price of competing products,

![]() , are shares of prospective customers for the novel product who are currently buying products of other firms scattered across established industries. Each competing price is scaled to a quantity equivalent to a unit of the novel product. The value of the parameter,

, are shares of prospective customers for the novel product who are currently buying products of other firms scattered across established industries. Each competing price is scaled to a quantity equivalent to a unit of the novel product. The value of the parameter,

![]() , is determined based on the competing needs of the entrepreneur for a high price to generate profits to finance growth in productive capacity and for a low price to attract customers from competitors.

, is determined based on the competing needs of the entrepreneur for a high price to generate profits to finance growth in productive capacity and for a low price to attract customers from competitors.

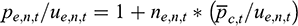

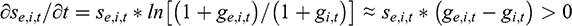

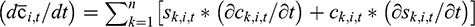

In the origination phase of the meso trajectory of a novel product is viable only if its price exceeds it unit cost. If

![]() is set equal to one and both sides of (3.5) are divided by unit direct cost of the novel product, the resulting equation for determining the product’s price-cost ratio is,

is set equal to one and both sides of (3.5) are divided by unit direct cost of the novel product, the resulting equation for determining the product’s price-cost ratio is,

(3.6)

(3.6)

The novel product is a value proposition to customers of competing products when,

(3.7)

(3.7)

This occurs only if

![]() , which only occurs if the unit direct cost for the novel product below the average price of competing products and the value of

, which only occurs if the unit direct cost for the novel product below the average price of competing products and the value of

![]() is substantially less than one.

is substantially less than one.

Keeping the price-cost ratio high during the origination phase generates profits to provide internal finance for investment in capacity expansion and can help in attracting external finance. Perhaps, even leading to acquisition by venture capitalists or an established firm with cash flow to invest in rapid expansion of production capacity. Pioneering customers provide a market for limited output in the origination phase, even when the price of the novel product doesn’t provide much better value than alternatives.Footnote 8

During the adoption phase of the meso trajectory of the novel product, a key consideration is the threat of entry from imitators. The benchmark for prices of competing products shifts from the prices of established distant competitors to prices likely to be charged by imitators. Sylos-Labini (Reference Sylos-Labini1962) suggests the entry-limiting price is equal to the unit cost of a small-scale potential entrant. Prices above this level attract at least some entry. A trade-off exists between ceding market share to imitators and generating internal finance for expansion of production capacity, as discussed in Section 3.3.3.

In the retention phase of the meso trajectory for the novel product, there are imitators operating in the industry. Here, price dynamics depend on the interaction between the innovating firm and its imitators, who have unit direct cost that may be below, equal, or above those of the innovator. Price determination for this situation is a special case of price theory for industries disrupted by innovation, which is presented in Chapter 5.

Learning and specialisation of labour in production occurring during the adoption and retention phases of the meso trajectory for novel products contribute to sharp decreases in the cost of production. The dynamics of differential firm growth as discussed in Chapter 5 ensure that cost decreases pass into price decreases, with stable or falling price-cost ratios. Thus, a sharp downward path for prices of novel products relative to those of established goods and services is commonly observed. Witness the experience of prices for computers, mobile phones, electric vehicles, and internet services over recent decades.

3.4 Summary

Firms are heterogeneous, even across firms producing similar products. They face an uncertain future and operate with limited knowledge. Their behaviour is generally regulated by rules and routines, particularly for large firms and mega-firms, who depend on such rules and routines to coordinate the activities of many individuals with specialised knowledge and skills. These rules and routines vary across firms, contributing to the variety of firm behaviour.

Several dimensions of differences among firms are examined in this chapter. First, differences in firm size, scope, and organisation are addressed, with emphasis on differences between small, large, and mega-firms. Second, the orientations of firms are distinguished in terms of survival, profit, growth, and innovation. Third, price-maker firms are distinguished from price-taker firms, both in terms of market conditions facing the firms and the behaviours they adopt in response. Fourth, price leadership is discussed as involving both price-taker behaviour (for the followers) and price-maker activity (for the leader). Finally, the pricing analysis is applied to determining price for a novel product with pricing behaviour changing between the origination, adoption, and retention phases of the meso trajectory for the novel product.

Part II Meso

4 Market Order

Preliminary to the analysis of how prices are determined in an evolving economy, I consider the theoretical role of prices when an economy is experiencing development from within. In Schumpeter’s ([Reference Schumpeter1934] Reference Schumpeter1961, Reference Schumpeter1939) theory of economic development and the business cycle there are two roles for price information. Prices provide information to coordinate transactions and encourage efficient resource allocation, and they provide information to entrepreneurs and their financiers to use in assessing the profitability of potential innovations.

Schumpeter argues under normal economic conditions price information is reliable and transactions are well coordinated. Reliable price information is useful to entrepreneurs and their financiers in assessing the profitability of innovations, thereby supporting a wave of innovations. However, innovations disrupt normality, undermining the coordinating role of prices. Price information becomes less reliable, leading to a downswing in innovative activity that continues until the price system adjusts and more normal conditions return.Footnote 9

4.1 Coordinating Price

Schumpeter (Reference Schumpeter1939) refers to a theoretical norm for price in discussing the prices that occur when innovations are fully absorbed in the economy. Marshall, his followers, and Sraffians use related concepts of normal price and reproduction price, respectively, to refer to the prices that occur in the long period, when external disturbing influences have dissipated (Bloch Reference Bloch2022). Forces determining the long-period price in these approaches are conceptually distinct from each other (Bloch Reference Bloch2020).

For reasons explained in remaining chapters, especially Chapter 7, Schumpeter’s concept of a theoretical norm for prices is rejected as being logically incoherent and unhelpful in evolutionary price theory. Instead, coordinating price is suggested as an appropriate theoretical concept for price. The coordinating price is a price consistent with orderly exchanges between buyers and sellers in a market in the short period, but subject to change over time as the market develops from within. No concept of a disturbance-free or long-period price is offered for evolutionary price theory as disturbance is always present or emergent in the evolving economy. Evolutionary price theory is a theory of prices in motion.

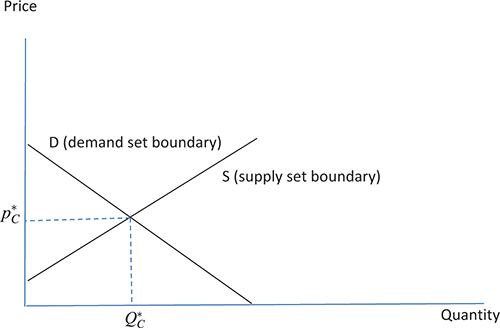

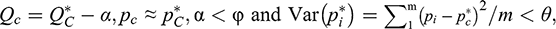

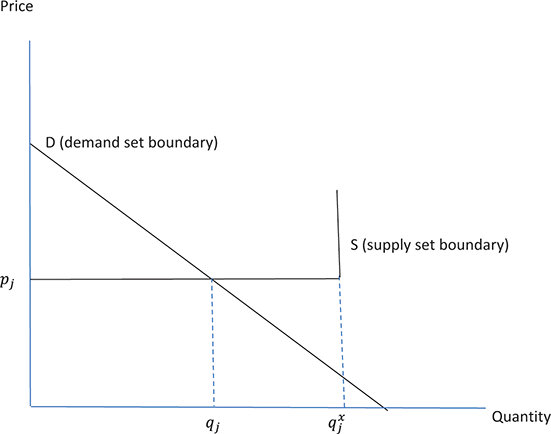

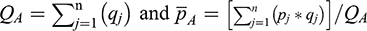

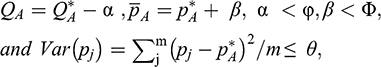

The remainder of this chapter discusses the role of price information in coordinating buyer and seller activities in an evolving economy. The concept of market order replaces the concept of market equilibrium in mainstream price theory. First discussed is price determination in orderly markets with large numbers of buyers and sellers, adapting the concepts of supply and demand to an evolutionary context. Following is a discussion of using administered prices to create order in markets dominated by a small number of sellers or buyers. With either market-determined prices or administered prices, coordinating price is the theoretical price concept for market order.