1 Introduction

The Russian invasion of Ukraine came on the heels of a series of crises that tested the resilience of the EU as a compound polity (Ferrera, Kriesi, and Schelkle Reference Ferrera, Kriesi and Schelkle2024). It has also, arguably, reshaped European policymaking at all levels and impacted the polity itself. This external threat triggered a debate between those arguing it can lead to an external security logic of polity building that serves as an impetus for (further) polity centralization in the EU, as per the ‘bellicist’ argument (e.g., Kelemen and McNamara Reference Kelemen and Kathleen2021) and those who doubt it (e.g., Genschel and Schimmelfennig Reference Genschel and Schimmelfennig2022). Taking the Russian invasion of Ukraine as a litmus test of the ‘bellicist’ argument, some contributions to the debate have questioned the extent to which it can really be conducive to polity centralization. The literature also casts some shadow of doubt on the extent to which such a threat is different than other threats and crises that the EU has been facing over the last couple of decades and the types of polity formation logics (external security vs. social security) it would trigger and their expected effects (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni Reference Eilstrup-Sangiovanni2022; Freudlsperger and Schimmelfennig Reference Freudlsperger and Schimmelfennig2022; Genschel and Schimmelfennig Reference Genschel and Schimmelfennig2022; Ferrera and Schelkle Reference Ferrera and Schelkle2024). Other contributions have explored specific topics such as the ways in which a rally around the European flag has evolved in the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine (Moise et al. Reference Moise, Natili and Oana2023; Truchlewski, Oana, and Moise Reference Zbigniew, Oana and Moise2023), or the nature of public opinion surrounding specific policies (Moise, Dennison, and Kriesi Reference Moise, Dennison and Kriesi2023; Wang and Moise Reference Chendi and Moise2023; Oana, Moise, and Truchlewski Reference Oana, Moise and Truchlewski2024). More generally, this debate is crucial for understanding the political dynamics that shape the current pathways of European polity formation.

This Element expands this debate in several ways and offers an empirically grounded analysis of the effects that the Russian invasion of Ukraine had on public support for European polity building in key policy domains. Focusing on public opinion support is important given the politicization of the European polity (Kriesi, Hutter, and Grande Reference Kriesi, Hutter and Grande2016), the debates on the democratic deficit in the EU and the weakness of voice channels (Bartolini Reference Bartolini2005), but also as a supportive public opinion offers an enabling environment for policymaking at the EU level and could take the wind out of Euroskeptic parties’ sails. While this Element is definitely not the first to focus on public opinion in the EU in times of crises (De Vries Reference Vries, Catherine, Vries and Catherine2018; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Altiparmakis, Bojar and Oana2024), it does bring in several theoretical and empirical contributions that offer unique analytical gains and novelty. These contributions are inspired by the polity approach to the European Union (Bartolini Reference Bartolini2005; Ferrera Reference Ferrera2005; Caramani Reference Caramani2015; Ferrera, Kriesi, and Schelkle Reference Ferrera, Kriesi and Schelkle2024) arguing for the multi-dimensionality and lack of finalité in European integration. In other words, the building of the EU polity need not imply a full transfer or new creation of ‘core’ institutions to the EU at the expense of the Member States. Instead, this approach acknowledges there can be a variety of polity-building pathways if one looks at the constitute elements of the EU as a polity (Ladi and Wolff Reference Ladi and Wolff2021; Ferrera, Kyriazi, and Miró Reference Ferrera, Kyriazi and Miró2024; Truchlewski et al. Reference Zbigniew, Oana, Moise and Kriesi2025).

First, in line with this approach, rather than conceiving of public support for the EU as uni-dimensional – more or less integration – we conceive of such support as playing out in two dimensions stemming from a distinction between ‘policy’ and ‘polity’ support. By policy support, we refer here to support for pooling decision-making and/or resources at the EU level in specific policy domains. By polity support, we refer to a general positive attitude to the EU based on a deeper loyalty towards the polity. In other words, policy support is analogous to specific support, while polity support is analogous to diffuse support for the EU (Easton Reference Easton1975). While specific and diffuse EU support have been related to one another in previous studies, we argue that they do not necessarily always go together and that studying their intersections opens up a richer analytical space in which public support for the EU can be categorized into four types: support for a centralized polity (high loyalty and high preference for pooling), decentralized one (low loyalty and low preference for pooling), pooled polity (low loyalty but high preference for pooling), or a reinsurance polity (high loyalty but low preference for pooling).Footnote 1

The second theoretical assumption that we start with is that crises are not monolithic threats. Crises play out in different policy domains and support for types of EU polity can vary across these domains as a function of the asymmetries that they exacerbate between countries and social groups, of the performance of European institutions and Member States in these crises, and/or of previous attitudes. These factors drive out territorial divisions – between citizens in different Member States – and functional divisions – between groups of citizens across Member States. In other words, akin to what the literature calls vertical differentiated integration (Holzinger and Schimmelfennig Reference Holzinger and Schimmelfennig2012; Dirk Leuffen and Díaz 2022; Schimmelfennig, Leuffen, and Vries Reference Frank, Leuffen and De Vries2023), support for the four polity types is policy domain-specific. This implies that there can be different polity-building pathways across policy domains, rather than a single logic of integration.

When it comes to the determinants of support for polity types across policy domains we, thus, inquire both into territorial divisions – between Member States – and into functional divisions – between social and attitudinal groups, within Member States. Concerning territorial divisions, we focus on the distribution of preferences for our four polity types between Member States and how these vary across policy domains. Concerning functional divisions, our manuscript brings together under the same umbrella three main sets of factors that have previously been associated with support for the EU. First, in line with the cleavage and post-functionalist literature (Vries and Edwards Reference Vries and Edwards2009; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009), we examine the relationship between ideational factors such as ideology and support for EU polity types. Second, going beyond deep-rooted attitudes, we also examine the relationship between crisis performance evaluations of both the EU and national governments as stemming out from the literature on output legitimacy (Scharpf Reference Scharpf1999; Jones Reference Jones2009; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2013). Finally, in line with more recent literature on external drivers of EU support, we look at factors related to the ‘bellicist’ argument and the hard security logic of EU polity building such as threat perceptions stemming from the invasion (Genschel Reference Genschel2022; Kelemen and McNamara Reference Kelemen and Kathleen2022; Truchlewski, Oana, and Moise Reference Zbigniew, Oana and Moise2023; Moise, Truchlewski, and Oana Reference Moise, Truchlewski and Oana2024), but also those related to a ‘Milwardian’ social security logic (Milward, Brennan, and Romero Reference Milward, Brennan and Romero1992; Natili and Visconti Reference Natili and Visconti2023; Ferrera and Schelkle Reference Ferrera and Schelkle2024) such as economic vulnerability. This allows us to examine and compare under the same theoretical and empirical umbrella the impact of both internal and external drivers of demand for different types of polities.

Beyond theoretically expanding the debate on EU support in light of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, we also empirically ground it by mobilizing a host of original public opinion data. Our Element relies on cross-national survey data that we contextualize using secondary source analyses of policy- and polity-making decisions undertaken in the EU during the invasion. Our empirical focus on public opinion is theoretically justified as, in line with the postfunctionalist literature (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009), we consider this to be one of the key mechanisms in the long causal chain between threats and polity formation (Truchlewski, Oana, and Moise Reference Zbigniew, Oana and Moise2023). Public support for both policies, but also for the EU polity at large, has the potential to tie or free the hands of policymakers at both the Member State and the EU level. At the Member State level, domestic policymakers are aware of the electoral consequences of their decisions and attempt to satisfy public opinion at home when making decisions on the EU stage. At the EU level, European policymakers have an interest in polity maintenance (Ferrera, Miró, and Ronchi Reference Ferrera, Miró and Ronchi2021; Ferrera, Kriesi, and Schelkle Reference Ferrera, Kriesi and Schelkle2024) and avoiding backlashes from domestic audiences. Nevertheless, beyond public support, we acknowledge that the structure of the polity in terms of how strong or weak its subunits are, how centralized, and so on, is important in shaping policy and polity responses to (external) threats (Genschel Reference Genschel2022; Moise, Truchlewski, and Oana Reference Moise, Truchlewski and Oana2024). We take this into account both by the fact that we examine the Russian invasion of Ukraine not as a monolithic threat spurring just an external security logic of polity-building, but as a series of threats affecting various policy domains in which the EU and the Member States have different competence distributions and powers at the centre of the polity might differ, and by examining both policy and polity support. In sum, by contextualizing public opinion in various policy domains and under the various decisions undertaken in these domains during the invasion, we also inquire into the ways in which the structure of the polity itself is shaping public opinion support.

We further these empirical goals by using original public opinion data collected within the ERC Synergy project SOLID at three-time points (March, July, and December 2022) after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, forming an original three-wave panel in five countries (Germany, France, Italy, Hungary, and Poland) with an additional two countries (Finland and Portugal) studied only in the second wave. Panel data has the unique advantage of tracking individuals over time enabling an examination of how their attitudes shift in response to the changing conditions of the conflict. It also allows more in-depth exploration of the interplay between attitudes, such as crisis performance evaluations, and security conditions, such as vulnerabilities enhanced by the war. Our panel data, therefore, allows us to study the dynamics of EU public opinion through a critical juncture for EU policy and decision-making. The EU and its Member States are directly involved in the war, through refugee acceptance, sanctions, energy policy, military aid, humanitarian relief, and other geopolitical and national decisions. Russia itself claims that it is at war not just with Ukraine, but with the whole of NATO. European publics have, therefore, been exposed to a geopolitical struggle between the West and Russia, with the EU taking a strong role. They have been exposed to the quick, emergency-style, consensual policymaking of the beginning of the war, as well as to the later disagreements among member states over sanctions, energy policy, and grain exports. Respondents have been exposed to the terrifying images of war crimes and, particularly in Eastern countries, also to the threat of Russian aggression and possible escalation. Our period of study, therefore, captures what is, to date, the most salient external threat to the European polity. It is, therefore, the ideal scenario in which to test the ‘bellicist’ argument, starting from the demand side.

To sum up, our Element brings in several key contributions to the debate on EU polity building in the aftermath of the invasion:

First, we seek to address the debate by delving deeper into the polity formation logics that are triggered across policy domains. Our Element pushes forward a distinction between ‘policy’ and ‘polity’ dynamics. By policy dynamics, we refer here to the specific support for decisions in various policy domains concerning the distribution of the burden of the shock across these policies among Member States. By polity dynamics, we refer to the shape and evolution of diffuse support for the EU based on a deeper loyalty towards the polity. By analogy, the polity is the container, while policies are what is contained. We argue that this distinction is important for capturing the various polity formation pathways upon which Europe can embark within crises. Rather than conceiving of public support for the EU as uni-dimensional – more or less integration – we conceive of such support as playing out in these two dimensions. Studying the intersections between these dimensions opens a richer analytical space for categorizing public support for the EU. We, hence, propose four polity types at the intersection of policy/specific and polity/diffuse support: a centralized polity (high loyalty and high preference for pooling), a decentralized one (low loyalty and low preference for pooling), a pooled polity (low loyalty but high preference for pooling), and a reinsurance polity (high loyalty but low preference for pooling).

Second, in contrast to what has been labelled as the ‘bellicist’ argument, we argue that the Russian invasion of Ukraine exerted pressures on a variety of different policy domains with the potential to spur not only an external security logic of polity building (i.e., centralizing the defence domain as a consequence of the external threat) but also other logics of polity building such as a social security one – that is, centralizing of risk and redistribution in other policy domains to cope with the fallout of the crisis (Moise et al. Reference Moise, Natili and Oana2023). In this Element, we further develop this idea that crises are not monolithic threats, but rather that they play out in different domains and support for EU polity types can vary across these as a function of the asymmetries that they exacerbate between countries and social groups. Consequently, the EU itself is not viewed as subject to more or less integration uniformly across the polity, but can be conceived of as an amalgamation of different polity types across policy domains. This idea structures the content of the Element as we analyse four highly salient policy domains on which the Russian invasion of Ukraine induced high pressures for reform – refugee policy, energy policy, foreign policy, and defence – while also focusing on the similarities and differences between them.

Third, we contribute to the literature on the internal and external drivers of European polity formation and their relative weight. While the literature on European integration has classically been focused on internal drivers of polity formation, political economists have long been acquainted with the idea of the ‘second image reversed’ in international politics (Gourevitch Reference Gourevitch1978), that is, the idea that external crises affect domestic political cleavages and thus shape the policy response and the development of any polity (Rogowski Reference Rogowski1989; Midford Reference Midford1993; Alt et al. Reference Alt, Frieden, Gilligan, Rodrik and Rogowski1996). The same is true of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and its influence on the formation of the European polity (Moise, Truchlewski, and Oana Reference Moise, Truchlewski and Oana2024). It is only recently that scholars started paying attention to the mechanism of external threats influencing the EU (Kelemen and McNamara Reference Kelemen and Kathleen2022), leveraging an old literature on the sources of state-building and federalism (Riker Reference Riker1964; Tilly Reference Tilly1975). We compare the impact of internal and external drivers of demand for different types of polities.

Fourth, our Element attempts to further empirically ground the debate surrounding the polity formation consequences of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In doing so, we critically focus on public opinion as an important link in the chain of polity formation given the politicization of the European polity, criticism of democratic deficit in the EU and of weak voice channels, but also as a supportive public opinion offer an enabling environment for policymaking at the EU level. In light of this, the Russian Invasion of Ukraine and its impact on the European polity offers a critical case study of the linkage between public opinion and polity formation. Empirically, we use a host of original public opinion data consisting of a unique three-wave panel survey on the topic of EU polity building following the invasion.

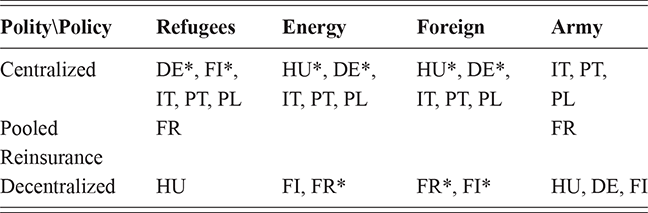

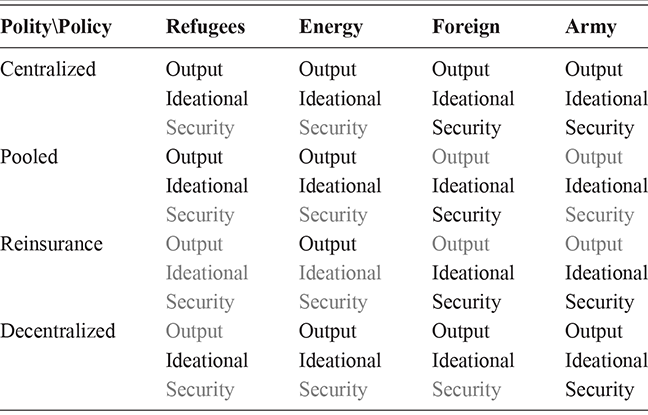

Across the four empirical sections, we show that all four polity types that we conceptualize at the intersections between policy and polity attitudes (centralized, decentralized, pooled, and reinsurance) are supported by large percentages of European publics. These results illustrate that two categories of citizens that are largely ignored in studies of EU support, those who want to centralize decisions in particular domains but have low loyalty towards the polity and those who, while having high loyalty, still do not want to centralize, constitute significant groups across all of our policy domains. In terms of the determinants of EU support, we show that performance evaluations and ideational factors are significantly related to preferences for polity types across all four domains, while external factors such as perceived threats and economic vulnerability stemming from the invasion have a lower impact. These results hold not only when examining static relations between these attitudes but also when examining within-individual change across the crisis. Hence, preferences for our four polity types are more strongly rooted in output legitimacy and deep attitudinal variables, rather than in factors directly related to the security or economic threats raised by the war. Beyond these attitudinal divisions, our results also show important territorial divisions between citizens in different Member States, divisions which vary greatly across policy domains. While countries are hardly divided over refugee policy (with the exception of Hungary), across the other three policy fields studied in the manuscript we observe varying potential ‘coalitions’ of citizens across Member States likely as a consequence of the asymmetrical impact of the crisis.

The Element proceeds as follows. Section 2 sets the scene by introducing the theoretical framework and the empirical design. Sections 3–7 examine EU support across the four policy domains chosen: refugee policy (Section 3), energy policy (Section 4), foreign policy (Section 5), and defence (Section 6). Each of these empirical sections starts with a descriptive analysis of support for the four polity types that we introduce in our theoretical section. It then analyses statically the territorial divisions in such support and the relationship between individual factors related to performance evaluations, ideational factors, and security factors. Finally, each empirical section includes a dynamic analysis of within-individual attitudinal changes over time. The Element ends with a concluding section where we summarize our theoretical contributions as well as our empirical findings and discuss their wider implications.

2 EU Polity Support – A Theoretical and Empirical Framework

This section lays out the theoretical and empirical design of our Element. We begin by justifying our focus on public opinion, emphasizing its critical role in the context of the increasing politicization of the European polity and its influence as an enabler of European policymaking. We then focus on the conceptualization of the demand-side support for EU polity building in times of crises, putting forward two significant contributions inspired by the polity formation approach to the European Union (Caramani Reference Caramani2015; Ferrera, Kriesi, and Schelkle Reference Ferrera, Kriesi and Schelkle2024). First, in line with this approach arguing for the absence of a clear finalité in the process of European integration, we say that the building of the EU polity does not necessarily imply a full transfer of sovereignty or the creation of ‘core state power’ institutions at the EU level. By contrast, there can be a variety of polity-building pathways that need not imply centralization at the EU level (Ladi and Wolff Reference Ladi and Wolff2021; Ferrera, Kyriazi, and Miró Reference Ferrera, Kyriazi and Miró2024; Truchlewski et al. Reference Zbigniew, Oana, Moise and Kriesi2025). We leverage this insight and propose a four-fold typology of support for the EU polity stemming from a distinction between polity and policy attitudes. Second, we argue that crises are not monolithic threats but that they instead exacerbate divisions between Member States (territorial) and social groups (functional) that vary across policy domains. In light of this, we introduce the policy domains that this Element focuses on and theorize the kinds of divisions that are likely to be associated with polity support across these domains. When discussing these divisions and the drivers of EU policy support we bring under the same theoretical and empirical umbrella both internal – such as output legitimacy and ideology – and external – such as threat perceptions – factors influencing support. Finally, we conclude the section by briefly introducing our data and the design of the empirical analyses.

2.1 Public Opinion and the EU Polity Formation

Since 1992, the politicization of European polity formation has brought public opinion into the picture of European politics (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009). The 1992 referendum failure in Denmark, which rejected the Maastricht Treaty, and the reluctant ‘little yes’ uttered by French voters marked the end of the permissive consensus and elite-driven European polity formation. More than ever after a decade-plus of crises, the EU relies on different types of support from electorates. Polity building – as embodied by the many reforms and capacity building at the centre – needs to be fully supported by voters to be sustainable in the long run and not exploited by euro-skeptic party actors. We, thus, argue that mapping out potential conflicts – whether functional or territorial (Caramani Reference Caramani2015) – is vital for understanding where political frictions can appear and how they will influence the future of both European polity formation and the Russian invasion of Ukraine (since Ukraine relies on its European allies for crucial help).

While the argument of external threats inducing polity centralization that stems from the state-building literature (Riker Reference Riker1964; Hintze Reference Hintze and Gilbert1975; Tilly Reference Tilly1975; Kelemen and McNamara Reference Kelemen and Kathleen2021) has been chiefly focused on the supply side of politics (policymakers) and does not have much to say about public demand for polity centralization, we argue that the demand side is an important link in the chain going from the external threat to polity centralization (Truchlewski, Oana, and Moise Reference Zbigniew, Oana and Moise2023).

First, the Hintze–Riker–Tilly thesis was developed to explain state formation in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance when elites operated without much popular constrain and when military technology required economies of scale that needed to go beyond the feudal structure (Cederman et al. Reference Cederman, Galano Toro, Girardin and Schvitz2023). Modern democratic nation-states need to consider public opinion, as it may constrain or enable elite action. We know that a strong dissensus among the European public can constrain further political integration (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009). Conversely, a strong consensus allows greater room of manoeuvre for politicians to steer the shape of the EU polity. At the Member State level, domestic policymakers are aware of the electoral consequences of their decisions and attempt to satisfy public opinion at home when making decisions on the EU stage. At the EU level, European policymakers have an interest in polity maintenance and, hence, avoiding backlashes from domestic audiences that could threaten the polity and bring about divisions that would undermine common decision-making (Ferrera, Miró, and Ronchi Reference Ferrera, Miró and Ronchi2021; Ferrera, Kriesi, and Schelkle Reference Ferrera, Kriesi and Schelkle2024).

Furthermore, we note that public opinion is more likely to exert pressure on politicians during times of high salience when voters follow what is happening and have more well-formed preferences. The present moment is, therefore, an opportunity to probe into demand-side dynamics at a time when the public is particularly attuned to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the response of the EU. Footnote 2 We started our panel survey at the onset of the invasion in 2022, a moment of very high salience for the Russian war in Ukraine and the economic and political response of the EU. Thus, while several of the policy domains associated with the invasion (foreign policy, energy, etc.) are usually considered too complex for individuals and of low salience, our timing allows us to examine them in a situation when the public is aware and engaged in discussions surrounding the implications of these policies. Indeed, several elections, such as those in HungaryFootnote 3 and Slovakia,Footnote 4 showed that policies concerning the war were crucial for electoral success. All in all, we argue that in case of an external threat, when highly salient policies take centre stage in the public sphere, consensus on the demand side becomes crucial for policymaking.

Second, and more generally, following the polity approach to the European Union (Bartolini Reference Bartolini2005; Ferrera, Kriesi, and Schelkle Reference Ferrera, Kriesi and Schelkle2024) that draws on the Hirschman-Rokkan model of state-building (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1970; Rokkan et al. Reference Rokkan, Flora, Kuhnle and Urwin1999), we look at bonding as one of the main elements characterizing a polity (alongside bounding–borders and binding–authority/capacity).Footnote 5 Bonding refers to the loyalty and solidarity that members of a polity have towards the polity itself and towards other members, a loyalty that ultimately constitutes the political community (Oana and Truchlewski Reference Oana and Truchlewski2024). Investigating how thin or volatile such bonding is in times of crises on the demand side is important as it speaks not only to the amount of resistance there is in the EU against pooling resources and decisions in particular policy domains but also to the potential for triggering more foundational conflicts over the raison d’être of the polity itself (Ferrera, Kriesi, and Schelkle Reference Ferrera, Kriesi and Schelkle2024).

Nevertheless, we do not yet have a good understanding of how the demand side of politics is affected by external threats and by the Russian invasion of Ukraine in particular. The evidence so far shows that similarly to the COVID pandemic (Altiparmakis et al. Reference Altiparmakis, Brouard, Foucault, Kriesi and Nadeau2021; Beetsma, Burgoon, and Nicoli Reference Beetsma, Burgoon and Nicoli2023; Bremer et al. Reference Bremer, Kuhn, Meijers and Nicoli2023), the Russian invasion of Ukraine triggered a rally-round-the-flag moment among European voters, who became more supportive of leaders and policies following the start of the war (Steiner et al. Reference Steiner, Berlinschi and Farvaque2023; Truchlewski, Oana, and Moise Reference Zbigniew, Oana and Moise2023; Nicoli et al. Reference Nicoli, van der Duin and Beetsma2024). Importantly, this implies that EU elites have greater room for manoeuvring in order to pursue certain forms of polity building. Conversely, if far-right parties are not able to capitalize on possible dissensions, they may prove unable to create political momentum against policies and polity formation, as postfunctionalism would predict (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009). However, as we further argue in the next section, such a rally-round-the-flag is likely to vary across policy domains. Furthermore, support might be short-lived and give way to more dissensus as the crisis progresses. By focusing on the demand side of politics, our manuscript aims to shed light on these developments.

2.2 Beyond Integration: Conceptualizing Polity Support across Policy Domains

We argued that analyzing the demand side of EU politics in the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine is important given the war’s public salience and given public opinion’s crucial role in enabling or constraining policymaking. While this Element is definitely not the first to focus on public opinion in the EU in times of crises (De Vries Reference Vries, Catherine, Vries and Catherine2018; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Altiparmakis, Bojar and Oana2024; Truchlewski et al. Reference Zbigniew, Oana, Moise and Kriesi2025), it does start from two consequential theoretical assumptions inspired by the polity approach to the European Union (Caramani Reference Caramani2015; Ferrera, Kriesi, and Schelkle Reference Ferrera, Kriesi and Schelkle2024) that bring about unique analytical gains and novelty. First, rather than considering public support for the EU as uni-dimensional – more or less integration, we conceive of such support as playing out in two dimensions stemming from a distinction between ‘policy’ and ‘polity’ support. Second, we argue that crises are not monolithic threats but that they play out in different policy domains, and support for types of EU polity can vary across these domains. In this section, we elaborate on both of these arguments.

2.2.1 A Typology of Public Support for the EU

Europe is at a crossroads: repeated crises are reshaping it since the mid 2000s, oftentimes in counter-intuitive ways. Most surprising perhaps is an outcome that did not happen: contrary to what many established theories predicted and in spite of what many politicians and analysts wish, Europe did not ‘integrate’ uniformly across policy fields into a fully-fledged federation (Tilly Reference Tilly1990; Kelemen and McNamara Reference Kelemen and Kathleen2021). Nor did the EU disintegrate and decentralize policy fields after massive policy failures (Vollaard Reference Vollaard2014; Leruth, Gänzle, and Trondal Reference Leruth, Gänzle and Trondal2019). Rather, new forms of collective policymaking appeared following the tectonic pressures of various crises: for instance, the EU started elaborating a ‘reinsurance regime’ (Schelkle Reference Schelkle, Cramme and Hobolt2014, Reference Schelkle2017, Reference Schelkle, Adamski, Amtenbrink and de Haan2022, Reference Schelkle, Moschella, Quaglia and Spendzharova2023a, Reference Schelkle2023b; Truchlewski et al. Reference Zbigniew, Oana, Moise and Kriesi2025) where the EU acts as a backstop of last resort for European member states. European capacity building is comparatively thin, and its main purpose is to ‘rescue the nation-state’, as Milward famously put it. Other forms of (un-)intended collective policymaking have been theorized (e.g., ‘extensive unification’ - Ferrera, Kyriazi, and Miró Reference Ferrera, Kyriazi and Miró2024; Truchlewski et al., Reference Zbigniew, Oana, Moise and Kriesi2025 or ‘coordinative Europeanization’ - Ladi and Wolff, Reference Ladi and Wolff2021), and the main message is that we need an approach that captures them. These unintended outcomes of European polity formation in hard times underline that polities can form along different pathways – from centralized nation-states to federations and confederations, to name but a few (Stepan Reference Stepan1999). While the unintended consequences argument (‘spillovers’) has always been a key argument of neofunctionalist theories of European integration (Haas Reference Haas1958), the neofunctionalists also stress the idea of a general upward trend towards further integration which crises might just delay (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2019). By contrast, the polity approach, resting on a historical-institutional argument, stresses the importance of not just path dependence, but also critical junctures such as crises, which open the door for different polity formation pathways (Pierson Reference Pierson1996). Finally, and since the EU is also a democratic polity, public opinion plays a crucial role in shaping which polity pathways will be taken: this is because public opinion constrains decision-makers and sets the parameters not only of the possible but also of the probable (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009).

When it comes to Europe, however, the probable is too often reduced to a binary choice. Policy-makers and their electorate may choose either more or less integration. The postfunctionalist literature (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018), while informative in bringing a demand-side focus in the study of European integration, also tends to model support for or against Europe in an uni-dimensional fashion (more or less integration) which we argue that does fully cover the multi-dimensionality that public preferences surrounding the EU can take. The same problem belies the state formation literature which more often than not assumes that in times of crisis, only one logic dominates polity building: the external security logic (Tilly Reference Tilly, Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985, Reference Tilly1990; Kelemen and McNamara Reference Kelemen and Kathleen2021), that is, the need to centralize coercive means at the centre of the polity to reap the benefits of economies of scale, organized communication and centralized command-and-control. Consequently, citizens can mostly express feelings towards more or less centralization. Such binary choices, we argue, do not reflect wide possibilities of what are probable polity formation pathways. For instance, Europeans can decide to pool decision-making processes, but not necessarily their material capacities. A case in point is the push for greater majority voting in the Council whilst leaving material levers of action at the national level. We argue that capturing such polity pathways is best addressed not only by asking whether citizens want more or less integration but rather by inquiring into what type of integration they want.

Other recent contributions to the study of EU support have also taken stock of the insight concerning the multi-dimensionality of support (for instance Boomgaarden et al. Reference Boomgaarden, Schuck, Elenbaas and de Vreese2011; Anderson and Hecht Reference Anderson and Hecht2018; Leuffen, Schuessler, and Gómez Díaz Reference Leuffen, Schuessler and Gómez Díaz2022; Schüssler et al. Reference Schüssler, Heermann, Leuffen, de Blok and De Vries2023 and in particular De Vries Reference Vries, Catherine, Vries and Catherine2018). In line with this insight, to avoid conceptual ambiguities, we propose to expand the analytical space that captures the various pathways that Europe can embark on when crises force decisions and reforms. Thus, rather than conceptualizing public support for the EU as uni-dimensional – more or less integration – we conceive of such support as playing out in two dimensions stemming from a distinction between ‘policy’ and ‘polity’ support. This distinction is based on the classic differentiation between specific (policy) and diffuse (polity) support (Easton Reference Easton1975). In line with this, support can be both specific for certain policies and diffuse for the polity itself more generally. The policy dimension, akin to specific support, refers to domain-specific attitudes related to the pooling of resources and/or decisions through different mechanisms like centralization or coordination to share the burden in a particular domain. In other words, this relates to what is ‘contained’ within the polity, that is, how much decisions and/or capacities are pooled in the centre of the EU. The polity dimension, akin to diffuse support, refers to attitudes related to a deeper loyalty towards the polity. These attitudes relate to the ‘container’ – the polity itself. Recent literature has highlighted that support for policies – the contained – is also conditional on their institutional design – the container (Burgoon et al. Reference Burgoon, Kuhn, Nicoli and Vandenbroucke2022; Bremer et al. Reference Bremer, Kuhn, Meijers and Nicoli2023; Beetsma, Burgoon, and Nicoli Reference Beetsma, Burgoon and Nicoli2023; Ferrara, Schelkle, and Truchlewski Reference Ferrara, Schelkle and Truchlewski2023; Nicoli, Duin, and Burgoon Reference Nicoli, van der Duin and Burgoon2023; Blok et al. Reference Blok, Heermann, Schuessler, Leuffen and de Vries2024). Hence, we investigate such specific and diffuse types of support by looking at support for, respectively, European policies and the European polity itself.

While specific and diffuse EU support have been related to one another in previous studies, we argue that they need not always correlate and that their intersections open a richer analytical space in which public support for the EU can be categorized. Hence, we propose a two-by-two typology (see Table 1) that categorizes support for the EU into four possible polity types: support for a centralized polity, a decentralized one, a pooled polity, or a reinsurance polity. While the concept of European integration only captures the first two of these and conflates the other categories into one of these extremes, we show across the four empirical sections that all four of these categories are supported by large percentages of European public and a sizable share of respondents locate themselves in the pooled and reinsurance types of polities. Note that these categories are ideal types that need not represent the status-quo in specific policy fields. The three categories are forward-looking and akin to ideal types: they signify preferences for possible polity formation pathways, rather than represent the status-quo in these specific policy areas. We argue that this typology gives us a much more fine-grained conceptual apparatus to empirically engage with support for the EU and to map theoretically richer possible outcomes.

Table 1 Pathways of EU polity formation

| Pathways of EU polity formation | Polity | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Partially/Not loyal | More/Fully loyal | ||

| Policy | More/Full centralization | Pooled | Centralized |

| Partial/No centralization | Decentralized | Reinsurance | |

The first possible type of EU support and polity formation pathway is that of a centralized polity. Citizens preferring this type of polity not only have a high loyalty towards the polity (e.g., high diffuse and general preferences for integration) but also want means/structures to be centralized in particular policy domains. By contrast, at the opposite end of the spectrum, we have citizens who prefer a decentralized polity. These citizens have low loyalty towards the polity and do not want to centralize means or structures. The first of the new categories that our typology brings in is that of the pooled polity. Citizens preferring such a polity have low loyalty towards the polity but want centralization in particular policy domains. Citizens in this category might want to pragmatically pool resources to face a shock, especially when subunits might have weak ‘infrastructural capacity’ (Mann Reference Mann2012; Genschel and Jachtenfuchs Reference Genschel and Markus2014). Finally, the other new category that our typology brings in is that of the reinsurance polity in which high loyalty is coupled with low preferences for pooling means or structures in particular policy domains (Schelkle Reference Schelkle2017, Reference Schelkle, Adamski, Amtenbrink and de Haan2022, Reference Schelkle, Moschella, Quaglia and Spendzharova2023a, Reference Schelkle2023b). This category draws from the idea that strong loyalty does not necessarily imply preferences for further capacity building. In general, it is not a foregone conclusion that subunits will pool resources: if the subunits have a strong ‘infrastructural capacity’, they will be reluctant to pool resources because the opportunity cost of doing so is losing political control (vs. creating new ex nihilo resources at the centre does not have this opportunity cost).

The two new categories that our typology introduces, pooled and reinsurance, also speak to competence and control theories of indirect governance (Genschel and Jachtenfuchs Reference Genschel, Markus, Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2013; Abbott et al. Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2020). These theories highlight the idea that any problem of governance is under-girded by principal-agent dynamics: principals face a dilemma between delegating to agents for more efficient action (competence) and controlling these agents so that they fulfil the task they are assigned to and do not exploit information asymmetries to pursue their own goal (control). In any polity, delegating competence without control can be politically perilous. Conversely, too much control over delegated competence can stifle efficiency. The problem of control also refers to the need for polity centralization: for any collective action to be efficient, agents also need to impose control so that principals do not renege on their initial commitment to common problem-solving. Hence, the need for common rules and institutions that enforce them.

Analogously, we could say that the pooled polity type stresses competence over control. In other words, supporters of the pooled polity type are pragmatists in that they want efficient solutions to policy-specific problems even if these solutions might imply the pooling of means away from principals – in the EU polity these would be the Member States. By contrast, the reinsurance type stresses control over competence: supporters of this type want control at the centre of the polity but with competencies remaining in the hands of the principals. Hence, our reinsurance type is akin to the regulatory polity stressing integration by regulation (Genschel and Jachtenfuchs Reference Genschel, Markus, Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2013) as core-state powers (and pooling of means) would remain firmly at the member-state level, but the EU would have regulatory control over these powers and a capacity to support member states when these cannot cope with extraordinary events (Schelkle Reference Schelkle, Cramme and Hobolt2014, Reference Schelkle2023b). However, while in these theories integration by regulation is opposed to integration by capacity building – integration that puts the EU on the pathway to state-building, our typology stresses that capacity building or the pooling of means can also be further differentiated. While a centralized polity would indeed imply capacity building but one that is placed on a firm basis of loyalty and with increased control and permanence at the centre, the pooled category refers to more pragmatic forms of centralization across policy domains that do not necessarily imply a mustering of core-state powers and needn’t be permanent.

A final note is worth mentioning related to the variation possible between the polity types within and across policy domains, but also across time. Polity-diffuse support is not policy domain-specific and hence does not vary across these domains, while policy support related to the decisions to centralize and pool resources are domain-specific. This implies that within each policy domain the four cells in our category can be of varying sizes, but when comparing between policy domains the size of the various support groups changes across vertical lines (from pooled to decentralized, or from centralized to reinsurance) in our Table 1 with the horizontal divisions in polity remaining stable across domains (i.e., the sum of the non-loyal group, with pooled and decentralized together staying constant across domains). Nevertheless, regarding variations over time, both vertical and horizontal variations are possible. Concerning the latter, polity attitudes can also change through time: as the crises progress, citizens’ loyalty to the polity might, for example, increase, and they could move from the pooled type to the centralized type, or from the decentralized type to the reinsurance type. As the forthcoming sections show, all these types of movements are observed empirically.

2.2.2 Public Support for the EU across Policy Domains

Our second contribution is to show that this four-fold analytical space applies to different degrees to different key policies. We argue that crises like the Russian war in Ukraine are not monolithic threats, but they operate through different channels of policy and polity preferences. In line with this, the external security logic can be complemented by other logics of polity formation kicking in: the social security logic (Moise et al. Reference Moise, Natili and Oana2023), that is, the need for every polity and polity response to be focused on redistribution and sustaining prosperity or, for instance, the legal logic of polity formation (Strayer Reference Strayer1970; Kelemen Reference Kelemen2011; Pavone Reference Pavone2022) through the emergence of an autonomous legal order. Accordingly, pooling means and structures may more or less be supported in some policy domains that others, which again underscores the idea that European integration is not a one-way street in the citizens’ mind, but rather a plurality of possible paths along which a polity can be build which can unfold differently in different policies.

Studying preferences for these polity formation pathways is particularly relevant in the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine not only as one of the likely cases in which demands for centralization or pooling can increase, according to the bellicist argument, but also as the threat coming from the invasion is multi-faceted and can highlight specific policy vulnerabilities in a polity (Moise et al. Reference Moise, Oana, Truchlewski and Wang2024). Hence, contrary to the bellicist argument focused on defence centralization, we argue that the threats of the invasion play out in different policy domains and support four types of EU polity that can vary across these domains as a function of the asymmetries that they exacerbate between countries and social groups, the performance of European and Member state actors, or of previous attitudes. These factors drive out territorial divisions – between citizens in different Member States and functional divisions – between groups of citizens across Member States.

We select four key policy domains of high salience in the crisis: refugee, energy, foreign policy, and defence. These policy fields represent the main vulnerabilities of the EU polity in this crisis and are subject to varying degrees of division between and within Member States.

The influx of refugees is a direct result of the war, and refugee policy is one of the main vulnerabilities that the conflict exacerbates. Between Member States, the pressures coming from the refugee influx are highly asymmetric with some countries, such as Poland and Germany, receiving the bulk of Ukrainian refugees. Within Member States, refugee policy and burden-sharing are some of the most politicized issues by far-right parties. Such territorial and functional divisions stood behind the intense conflict and eventual stop-gap, externalization solution of the 2015 refugee crisis (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Altiparmakis, Bojar and Oana2024). Nevertheless, existing evidence suggests that in spite of these asymmetries, there is strong support for burden-sharing both between Member States and socio-political groups (Moise, Dennison, and Kriesi Reference Moise, Dennison and Kriesi2023).

Energy policy was directly weaponized by Russia as a way of punishing the EU for its support of Ukraine, and to fight back against other sanctions which could spur unity. Nevertheless, the energy threat induced by the crisis and the rising energy costs stemming from the energy transition are being experienced asymmetrically both between member states (given differences in energy dependence and geopolitical context), and within member states (due to various individual preferences and vulnerabilities) (Oana, Moise, and Truchlewski Reference Oana, Moise and Truchlewski2024). Such asymmetries can exacerbate transnational and domestic conflicts and can thus undermine common EU decision-making and solidarity.

The foreign policy of the EU is both a source of strength and weakness for the EU polity: due to the structure of its decision-making based on consensus and vetoes, the EU can either manage to speak with one voice – which makes it appear as united and strong – or can quickly descend into paralysis as even the smallest of its Member States can veto decisions. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that foreign policy is a domain in which economies of scale are much less tangible than in material policies like defence or energy. As a consequence of this, there is a high likelihood that Member States might wish to maintain autonomy and sovereignty. Furthermore, geopolitical factors such as proximity to the conflict zone might further exacerbate this problem: countries bordering a crisis-prone region may want to upload their policy solution to the whole polity, while countries far away may be reluctant to share the cost of a problem that is not theirs.

Finally, studying the defence domain is particularly important for studying the bellicist logic of polity formation: the threat stemming from the Russian invasion of Ukraine should result in more demand for centralization in the realm of defence. Nevertheless, this policy domain is characterized not only by the strength of the sub-units (Member States have highly developed national armies), but also by the external security guarantee provided by NATO both factors which might reduce the impetus for pooling and centralizing defence resources (Moise, Truchlewski, and Oana Reference Moise, Truchlewski and Oana2024). Furthermore, arming Ukraine is already highlighting tensions between member states over which weapons to send and how to reimburse other member states.

2.3 The Drivers of Support for EU Polity Types

The literature on public support for the European polity has already theorized its different potential drivers. Our aim in this manuscript is to bring them under the same comparative umbrella and analyse their relationship with our proposed measure of EU polity support across policy domains. In line with Caramani Reference Caramani2015 (but also more recent contributions to the literature on EU support or solidarity, Kriesi, Moise, and Oana Reference Hanspeter, Moise and Oana2024; Oana and Truchlewski Reference Oana and Truchlewski2024; Truchlewski, Oana, and Natili Reference Truchlewski, Oana and Natili2024) which points out to the importance of two types of cleavages when it comes to the EU: territorial cleavages between the Member States and functional cleavages which are transnational and cut across territorial lines, we also look at both types of factors throughout our analyses. With regards to territorial cleavages, we examine divisions in public support across Member States and how these vary across policy domains. In what regards functional divisions we examine the extent to which preexisting and deep-seated predispositions and attitudes such as ideology are related to EU polity support, but also look at the effect of crisis or policy-specific factors on such support. We focus on two such crisis or policy-specific factors which are rarely discussed under the same umbrella: output legitimacy (Scharpf Reference Scharpf1999; Jones Reference Jones2009; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2013), and security logics (Kelemen and McNamara Reference Kelemen and Kathleen2022; Natili and Visconti Reference Natili and Visconti2023; Ferrera and Schelkle Reference Ferrera and Schelkle2024) which have been put forward by various strands of literature on European polity formation. First, our framework integrating both territorial and functional divides speaks to the extent to which territoriality is dissipated within the EU across policy domain or replaced by cleavages cutting across these territories (Caramani Reference Caramani2015) as well as to the ways in which territorial and (post-)functional constraints could be re-enhanced, overcame, or bypassed altogether. Second, while the literature on European integration has classically been focused on internal drivers of polity formation, more recently scholars started paying attention to the mechanism of external threats influencing the EU (Kelemen and McNamara Reference Kelemen and Kathleen2021). Our framework aims to bring together and compare the impact of both internal and external drivers of demand for different polity types.

2.3.1 Territorial Divisions

A large part of the literature on support for European integration emphasizes territorial divisions between Member States and the ways in which such divisions can slow down or paralyze policymaking by giving rise to divergent territorial coalitions that make agreeing to common solutions harder. This literature argues that the asymmetries that crises create between Member States given their various vulnerabilities, the wider political and socio-economic national context in which citizens live, and the positions of their national governments structure their preferences (Ferrara and Kriesi Reference Ferrara and Kriesi2021). The crisis-focused literature has emphasized various transnational coalitions between member states in intergovernmental negotiations (Buti and Fabbrini Reference Buti and Fabbrini2022; Fabbrini Reference Fabbrini2022; Porte and Jensen Reference Porte and Dagnis Jensen2022). For example, in the Euro-Area crisis, the literature has pointed to divisions between creditor and debtor countries or ‘Northern Saints’ and ‘Southern Sinners’ (Matthijs and McNamara Reference Matthijs and McNamara2015). In the refugee crisis, Kriesi et al. (Reference Kriesi, Altiparmakis, Bojar and Oana2024) talk about a division between frontline states and open destination states (those receiving the bulk of refugees) and transit and closed destination states. In the COVID crisis, the literature (Kriesi, Moise, and Oana Reference Hanspeter, Moise and Oana2024; Truchlewski et al. Reference Zbigniew, Oana, Moise and Kriesi2025; Fabbrini Reference Fabbrini2022) highlights three main coalitions with divergent preferences: the ‘Frugal 4’ member states (Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden), the ‘solidaristic’ Southern countries (Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and one may add France), and the Visegrad four countries (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia). More recent studies (Kriesi, Moise, and Oana Reference Hanspeter, Moise and Oana2024) have shown that these transnational coalitions also play a role in the Ukraine crisis. In line with this and also starting from the assumption that such coalitions are also present in the aftermath of the invasion we examine territorial divisions between citizens in different Member States. We expect such divisions to matter, but we also expect them to vary across policy domains as a function of the Member State vulnerabilities that the crisis accentuates. We put forward our expectations in terms of the territorial divisions we foresee between these (or other) coalitions of member states in each particular policy domain in the respective empirical sections.

2.3.2 Functional Divisions

Ideational Factors

The second strand of theories explaining the demand for EU integration also uses cleavage theory (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967). This strand of theories argues that long-term social transformations are reshaping the structure of divides across the EU from territorial to functional divides that cross-cut across geography (Caramani Reference Caramani2015). This approach relates attitudes towards the European Union first and foremost to political ideology (Vries and Edwards Reference Vries and Edwards2009; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Hix and Høyland Reference Hix and Høyland2024). While some showcase the relationship between ideology and support for the EU as a U-shaped curve with those individuals that place themselves towards the centre of the left-right scale being more supportive of the EU than those that place themselves towards the extremes (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018), others (Hix and Høyland Reference Hix and Høyland2024) find that this relationship has changed dramatically over time as in the early years of European integration the right was more supportive of the EU, with this pattern reversing drastically after the 2000s. Generally, what the literature has in common is suggesting that the far-right has always been and still is associated with less support for the EU. Starting from this insight, we also expect that those citizens placing themselves towards the far right of the ideological scale would be less in favour of the three polity types that imply either high loyalty or pooling (centralized, pooled, and reinsurance) and more in favour of the decentralized polity type.

Output Legitimacy

Territorial and ideational explanations are usually robust indicators of EU support. However, given that territorial identities and ideology are rather stable as the result of deep-seated psychological predispositions they are expected to hardly change across policy domains or through time (Hooghe and Wilkenfeld Reference Hooghe and Wilkenfeld2008). By contrast, crisis and policy-specific factors can help us shed further light on such variation. The first set of such crisis/policy-specific factors that we look at are related to the discussion surrounding the criteria by which to evaluate the legitimacy of the EU. One such criterion that has been put forward in the previous literature is output legitimacy, and it refers to the effectiveness of the EU’s policy outcomes for the people (Scharpf Reference Scharpf1999; Jones Reference Jones2009; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2013). In line with this literature, we argue that citizens’ satisfaction with the management of a crisis and its results has a likely impact on their support for specific polity types. We, hence, expect that the perceived efficiency or inefficiency of the EU in managing the crisis should have an impact specifically on preferences for pooling. In other words, the more citizens are dissatisfied with the performance of the EU in a particular polity domain the less they prefer the centralized and the pooled polity type. We expect this argument to also hold through time: changes in how satisfied an individual is would be strongly related to changes in polity type preferences as the crisis progresses.

Furthermore, keeping in mind the multilevel structure of the EU polity and its strong sub-units, we also expect the performance of national governments in the crisis to impact polity preferences. This insight is based on the ‘benchmark’ theory that contends that EU support does not develop in a vacuum and citizens’ attitudes towards the EU are not only a result of how the EU itself performs but also a result of a comparison between national and EU evaluations (De Vries Reference Vries, Catherine, Vries and Catherine2018). In our case, if the strong polity sub-units, that is, the Member States, are already perceived as fairing well in dealing with the crisis this reduces the need for pooling. Hence, the more satisfied one is with the performance of their government in dealing with a particular aspect of the crisis, the less one would prefer pooling in that particular policy domain.

Security Logics

While the literature on European integration has classically been focused on internal drivers of polity formation (i.e., ideational and output legitimacy), it is only more recently that scholars started paying attention to the mechanism of external threats influencing the EU (Kelemen and McNamara Reference Kelemen and Kathleen2022), leveraging an old literature on the sources of state-building and federalism (Riker Reference Riker1964; Tilly Reference Tilly1975). This ‘bellicist’ argument arguing that external security constitutes a strong driver for polity formation and centralization is generally focused on the supply side of politics. By contrast, we have argued that in the current era of mass democracy, a strong dissensus or consensus among European publics can constrain or enable policymaking (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009). In line with this, more recent literature has attempted to translate the ‘bellicist’ argument to the demand side of politics (Genschel Reference Genschel2022; Truchlewski, Oana, and Moise Reference Zbigniew, Oana and Moise2023; Moise, Truchlewski, and Oana Reference Moise, Truchlewski and Oana2024). This literature suggests that security concerns may prompt citizens in different member states to close ranks and demand more EU polity building. Indeed, studies of political behaviour show that exceptional circumstances and major crises (Mueller Reference Mueller1970, Reference Mueller1973; Altiparmakis et al. Reference Altiparmakis, Brouard, Foucault, Kriesi and Nadeau2021; Bol et al. Reference Bol, Giani, Blais and John Loewen2021; Schraff Reference Schraff2021; Steiner et al. Reference Steiner, Berlinschi and Farvaque2023) give rise to moments of unity in which a majority of citizens show increased levels of political support. In other words, the perceived threat that a crisis poses can produce a rally-round-the-flag effect on the demand side, which would increase support for the EU. Following this strand of literature, we also use a measure of threat induced by the invasion and expect that the higher such threat, the stronger the preferences for pooling, that is, the higher the support for the centralized and pooled polity types.

However, while ‘bellicist’ theories focus on the impact of hard security threats on EU supports, others instead emphasize how the quest for social security is a strong driver of EU polity formation (Ferrera and Schelkle Reference Ferrera and Schelkle2024). This argument aligns with a ‘Milwardian’ (Milward, Brennan, and Romero Reference Milward, Brennan and Romero1992) view of EU polity formation indicating that in compound polities, since the sub-units are states with considerable capacity in core state powers (Genschel and Jachtenfuchs Reference Genschel and Markus2014), instead of a transfer of such powers to the centre what is expected is for the EU to act as a safety net of the Member States. Because of this centralized European polity formation is expected to be predominantly achieved in the economic field. In line with this argument, on the demand side, it is actually citizens’ demands for protection against social and economic risks that would increase their demand for the EU (Natili and Visconti Reference Natili and Visconti2023). Following the argument of the social security logic of EU polity building, we would expect that the economic vulnerabilities stemming from the invasion push citizens’ preference for pooling resources at the EU level.

2.4 Design of the Study

2.4.1 Data

We further our empirical goals by using original public opinion data collected within the ERC Synergy project SOLID at three-time points (March, July, and December 2022) after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, forming an original three-wave panel in five countries: Germany, France, Italy, Hungary, and Poland. The second wave of our panel also included respondents from Finland and Portugal. The selection was these countries was guided by the idea of obtaining a wide amount of country heterogeneity in terms of reliance on Russian gas, political discourse related to sanctions, centrality in the EU, and geopolitical location that allows us to map preferences in a wide range of contexts. As further detailed in what follows, when comparing our data with other data sources with a wider geographical coverage on particular items of interest, the selected countries are fairly representative of wider European trends. Interviews were administered on national samples obtained using a quota design based on gender, age, macro-area of residence (NUTS-1), and education. Our total sample size is approximately 33,000 observations, while our panel respondents include 6,000 individuals surveyed over all three waves.

The first wave was carried out between 11 March and 5 April 2022, two weeks after the start of the war. This period captures attitudes at the very start of the war when the conflict dominated media channels across Europe, and thus the initial rally-around-the-flag effect (Truchlewski, Oana, and Moise Reference Zbigniew, Oana and Moise2023). EU member states came together in an unprecedented manner to form a common front against Russian aggression, applying sanctions, receiving refugees, and providing support to Ukraine. Attitudes from this period also tell us whether the EU may have missed a critical juncture for policy and polity change if such attitudes did not last. The second wave of our panel was conducted between 8 and 28 July 2022. Five months into the war saw a large decrease in salience, as other topics, including inflation and a looming energy crisis, took centre stage. At the same time, the conflict appeared in stale-mate after the spring, when the Ukrainians pushed Russian forces out from the capital, and the fighting concentrated on the South and East. The third wave was administered between 14 December 2022 and 4 January 2023. In between the second and third waves, the Ukrainian army made significant gains in the fall of 2022, showing the importance of Western-provided weapons and support. The timing of our third wave captured a period of calm in the conflict, while EU decision-making was focused primarily on energy policy and rising inflation.

While we focus on seven key member states over a roughly ten-month time-period following the start of the war, our findings speak to broader cross-country and over-time trends. Figure 1 shows how support for an integrated EU army fluctuates from 2018 to 2024 in fourteen EU countries.Footnote 6 What can be seen is that the war is a clear critical juncture, drastically shifting support in most countries starting in 2022, as already noted in the literature (Genschel Reference Genschel2022; Truchlewski, Oana, and Moise Reference Zbigniew, Oana and Moise2023). We see three types of countries. In France, Germany, Poland, and the Netherlands, we see stable support across time. In Denmark, Finland, Lithuania, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, we see strongly increased support in 2022, following the invasion, with some reversion in 2023–2024, but overall higher support. Lastly, in Italy, Hungary, and Romania, we see a decrease in support following the Russian invasion. Our sample of seven includes countries from each category, allowing us to study these dynamics in depth. Our analysis confirms the pattern of increasing initial support, followed by a slight reversion and then stability in most countries.Footnote 7 Importantly, our more detailed original panel survey allows us to show how these trends differ across policy domains. Secondly, our original panel data allows us to go more in depth in terms of the significance of these time trends. What does it mean that a higher or a lower share of respondents support an EU army? We combine this data with views on EU integration and unpack the main drivers behind these shifting dynamics.

Figure 1 Support for EU army across time and EU countries

Panel data has the unique advantage of tracking individuals over time in order to see how their attitudes shift in response to changing conditions and the continuation of the conflict. It also allows more in-depth causal exploration of the interplay between ideology, output legitimacy, and security conditions. In addition to our panel structure, our series of surveys also included several experiments, which aimed to shed further causal light on questions surrounding the support for policies and the European polity.

Preliminary analyses using part of the data have been published (Moise, Dennison, and Kriesi Reference Moise, Dennison and Kriesi2023; Truchlewski, Oana, and Moise Reference Zbigniew, Oana and Moise2023; Wang and Moise Reference Chendi and Moise2023) and inform our current theoretical framework and empirical goals. Our preliminary findings suggest neither a complete endorsement nor a complete rejection of the ‘bellicist’ logic. Instead of focusing on the question of ‘whether the war resulted in polity-building’ we focus on what types of polity-building are likely, given what the demand side of politics can support. Much remains to be explored, including the temporal dynamics across the three waves.

2.4.2 Operationalization of the Polity Categories

In order to operationalize the four polity categories that form our dependent variable, we take a general measure of support for the polity and specific measures of support for the various policy domains. To measure support for the polity, we use a question that asks respondents whether EU integration should go further or whether it has gone too far.Footnote 8 This measure remains constant across policy domains. Footnote 9 Then, for each specific policy domain, we use questions asking whether in that specific policy area, the respondent would like to see more centralization at the EU level or not. While there might be multiple ways of policy-specific integration (e.g., integration in the energy field need not be done via the sharing of costs, but via other means), we use these indicators as they all represent salient policy proposals discussed at the EU level at the time of data collection.

Refugee policy: ‘Each EU country should be required to accommodate a share of refugees’. – 11-point scale Agree-Disagree;

Energy policy: ‘Some experts say that moving away from Russian gas is expected to affect some EU countries more than others in the short term. Which of the following statements comes closest to your view’. Answer categories:

– The cost of moving away from Russian gas should be a matter for each government individually;

– The cost of moving away from Russian gas should be shared between all EU member states;

Foreign policy: ‘Foreign policy decisions, such as decisions about war and peace, should be taken at the EU level, rather than at the level of the single member states’. – 11-point scale Agree-Disagree;

Military policy: ‘The EU should create its own army’. – 11-point scale Agree-Disagree.

In order to create the four groups and harmonize measurement across our policy fields, we dichotomize our 11-point scale measures. In doing so we opt for a conservative measurement of support for policy and polity, assigning the mid-point of the scales (5) to the lack of support categories. We, thus, consider only values above 6 to indicate support for the specific policy, or for the polity in our integration question. For energy policy we code the second answer category, of sharing the cost of moving away from Russian gas, as support for centralizing the policy. In order to create the four categories we assign respondents based on whether they support the polity and the specific policy, following Table 1. Thus respondents who support both are coded as favouring a centralized polity, neither as decentralized polity, favouring policy but not polity centralization as pooled, and favouring polity but not policy as reinsurance.

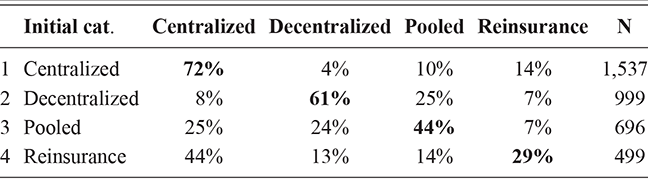

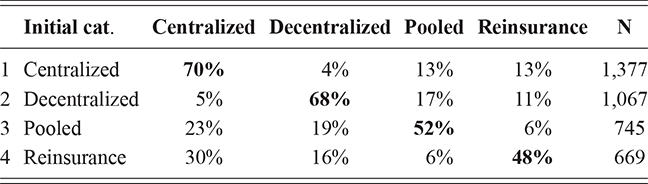

In addition to our cross-sectional analyses, we also investigate the drivers of over-time change between polity types. In each section, we discuss the dynamics of change between our waves. In so doing, we discuss the vertical (e.g., from centralized to reinsurance) and horizontal (e.g., from centralized to pooled) movements in figure 1 (and subsequent descriptive figures such as Figure 3), but not diagonal (e.g., from centralized to decentralized) changes. We do this in order to make the changes comparable. Vertical and horizontal change requires a respondent to change only one variable, whereas diagonal change requires them to change both. This means that for practical purposes a diagonal change is less likely, as we observe (see e.g., Figure 7). We discuss these changes in detail in each section.

More generally, our dichotomization could raise several concerns regarding respondents generally placing themselves in the middle of the scale, a high correlation of polity-policy attitudes, the robustness of the effects of independent variables on the disaggregated dependent variable, or losses of information in the analysis of change. We discuss these concerns more in depth in the Appendix (Sections 1, 4, and 5) to the Element where we show that the extremes of our scales represent sizable categories, that the correlation of policy–polity attitudes is smaller than expected, that the effects of our predictors are rather stable and in the expected direction on each of the two constituent variables, and also show more detailed results in the analysis of change.

2.4.3 The Determinants of Support and Modelling Strategy

Following our theoretical framework, we focus on three types of independent variables that may affect support for the different forms of the EU polity: satisfaction with performance at the EU and the national level, ideology, trust in Ukraine, and security factors such as threat perception and economic vulnerability. In the Appendix (Section 1) to the Element we present descriptive figures for these independent variables and their variation across countries and change over time.

We perform two types of analysis across the policy fields of interest to this Element: refugee, energy, foreign policy, and military policy. The first analysis is a static analysis of our second wave (8 to 28 July 2022), where we have the larger country sample, including Portugal and Finland. Due to the categorical nature of our dependent variable, we perform a multinomial analysis. We present the results in predicted probability plots for ease of interpretation. In addition, we also present an analysis of change between waves. We first present descriptives for how the relative proportions of each group in our dependent variable change between waves 1 and 2, and then 2 and 3. Given the large number of combinations of types of change (sixteen possible changes for each wave pairing), we limit our analysis to analyzing the change in the ‘centralized’ group, which we argue is crucial to understanding whether we can expect policy-specific polity formation.Footnote 10 We utilize multinomial models with country-fixed effects and include both level and change for our predictors. In interpreting results we focus only on the effect of changes in our predictors on whether individuals remain in the ‘centralized’ category or switch to one of the other three.

For both types of models, beyond our main explanatory variables included in the coefficient plots, we also control for trust in the government, interest in politics, and include country-fixed effects. Our analysis of change suffers from possible problems related to attrition in our sample. We conduct all change analyses on the same set of respondents, who were retained in the survey across all three waves and make up about 50 per cent of the original sample. Attrition analysis reveals that our sample remains mostly balanced, despite the attrition. Respondents who are retained differ in only two factors across our dependent and independent variables. Respondents who are interested in politics are about 10 per cent more likely to remain in the sample. Respondents who are in favour of an EU army are about 4 per cent more likely to remain in the sample. These modest effects, coupled with the fact that no other factors are significant, give us confidence that attrition does not present substantial bias in our analysis. The static analysis in wave 2 utilizes fully representative samples, which include the retained respondents from wave 1 together with new respondents until our original quotas were filled.

3 Refugee Policy

Between 2015 and 2022, refugee crises repeatedly tested the EU’s politics, albeit in different manners. The 2015–16 crisis unleashed political conflicts between frontline and destination states (e.g., Greece vs. Germany), undermined the EU’s capacity to act and find solutions (e.g., the failure of the quota system), and induced an anti-immigration backlash in public opinion. By contrast, the 2022 refugee crisis forced the EU to innovate to accommodate Ukrainian refugees by activating the Temporary Protection Directive (TPD). All in all, two different political dynamics unfolded as the two refugee crises played out in 2015 and 2022 (Moise, Dennison, and Kriesi Reference Moise, Dennison and Kriesi2023; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Altiparmakis, Bojar and Oana2024): while the far-right used the 2015 refugee crisis to garner votes, in 2022 it was less vocal. Likewise, elites and publics alike were less polarized and more welcoming of refugees in 2022 than in 2015. Finally, the refugee aspect of the Russian invasion of Ukraine was one of the most salient at the beginning of the invasion, when compared to other policy areas such as energy or defence (Moise, Dennison, and Kriesi Reference Moise, Dennison and Kriesi2023; Moise et al. Reference Moise, Oana, Truchlewski and Wang2024). In this section, we examine the nature, drivers, and temporal evolution of support for our four polity types in the refugee domain. In terms of structure, we start by descriptively mapping public preferences onto the four polity types identified in Section 2 (see Table 1): the centralized polity, the pooled polity, the reinsurance polity, and the decentralized polity. We then examine static territorial and (post-)functional divisions in these preferences before examining how changes in political attitudes over time are related to polity types.