5 - Form and Popular Culture

Summary

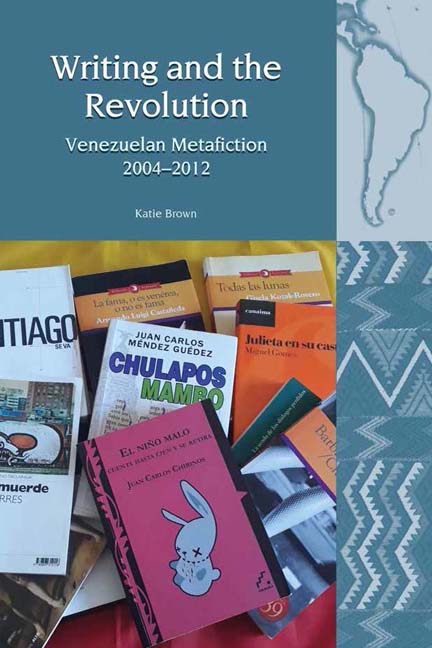

The incorporation of aspects of popular culture into literary texts is not new, but it takes on new significance in the context of the distinction between the popular as ‘lo nuestro’ [ours] and the elite as ‘apatriado’ [unpatriotic] in Bolivarian rhetoric. Moreover, the ‘popular’ as celebrated by the Bolivarian Revolution is defined by the national and often the indigenous, while popular culture in terms of globalised media is condemned as neo-imperialist. This chapter examines how a selection of novels – Bajo las hojas(Centeno, 2010), Chulapos Mambo(Méndez Guédez, 2011), Transilvania unplugged (Sánchez Rugeles, 2011) and El niño malo cuenta hasta cien y se retira(Chirinos, 2010) – involve aspects of popular culture, building on the spirit of aesthetic renovation that characterised the Punto Fijo period. ‘Popular’ is understood here in a variety of ways: as genres such as the gothic, comedy and detective fiction with mass appeal; as experienced by multitudes (global media and the internet); and as folk or indigenous. Using a combination of these aspects of popular culture allows these authors both to fulfil their literary aims, such as storytelling, building suspense or giving free rein to their imagination, and to comment on the socio-political realities of Venezuela under Chávez.

During the Punto Fijo period, the political and economic stability brought about with the transition to democracy led to aesthetic renovation (Barrera Linares, 2005), characterised by a diversity of styles and themes. Free from political obligations, authors could write about whatever subjects interested them, and did not have to fear censorship or punishment if they criticised the government (Porras, 2006, 626–627). Nonetheless, writers were discouraged from political radicalism through financial incentives from a state eager to maintain order, while, according to Ángel Rama (1982, 174), increased oil wealth had also created a middle class unwilling to jeopardise their new social position by supporting revolutionary movements. In this context, aesthetic concerns became the primary focus for many writers. Luis Britto García (1999, 50) suggests that, having lost hope in the possibility of improving society, writers began to strive for aesthetic perfection instead. At the same time, the state's use of oil revenue to fund publishing gave writers the economic freedom to be creative.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Writing and the RevolutionVenezuelan Metafiction 2004-2012, pp. 127 - 147Publisher: Liverpool University PressPrint publication year: 2019