Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part 1 Works

- Part 2 Impact

- Part 3 Approaches

- 9 King's Contestatory Intertextualities: Sacred and Secular, Western and Indigenous

- 10 Thomas King's Humorous Traps

- 11 “Have I Got Stories—” and “Coyote Was There”: Thomas King's Use of Trickster Figures and the Transformation of Traditional Materials

- 12 “One Good Story”: Storytelling and Orality in Thomas King's Work

- 13 Maps, Borders, and Cultural Citizenship: Cartographic Negotiations in Thomas King's Work

- 14 One Good Protest: Thomas King, Indian Policy, and American Indian Activism

- 15 “Sometimes It Works and Sometimes It Doesn't”: Gender Blending and the Limits of Border Crossing in Green Grass, Running Water and Truth & Bright Water

- Part 4 Encounters

- Part 5 Thomas King—A Bibliography

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

13 - Maps, Borders, and Cultural Citizenship: Cartographic Negotiations in Thomas King's Work

from Part 3 - Approaches

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2013

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part 1 Works

- Part 2 Impact

- Part 3 Approaches

- 9 King's Contestatory Intertextualities: Sacred and Secular, Western and Indigenous

- 10 Thomas King's Humorous Traps

- 11 “Have I Got Stories—” and “Coyote Was There”: Thomas King's Use of Trickster Figures and the Transformation of Traditional Materials

- 12 “One Good Story”: Storytelling and Orality in Thomas King's Work

- 13 Maps, Borders, and Cultural Citizenship: Cartographic Negotiations in Thomas King's Work

- 14 One Good Protest: Thomas King, Indian Policy, and American Indian Activism

- 15 “Sometimes It Works and Sometimes It Doesn't”: Gender Blending and the Limits of Border Crossing in Green Grass, Running Water and Truth & Bright Water

- Part 4 Encounters

- Part 5 Thomas King—A Bibliography

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

Summary

As numerous critics have pointed out, literal and metaphorical maps and mapping “are dominant practices of colonial and postcolonial cultures” (Ashcroft, Griffith, and Tiffin 2007, 28). Maps are a form of representation (“representational space,” as W. H. New has called them in Land Sliding), a construction of spatial relations and imagination, a form of control over space in the context of colonialism. But maps are also deployed as a strategy to counter hegemonic models of space. This is a central aspect for postcolonial societies, in which colonial inscriptions, for instance through cartography, are challenged and deconstructed in literary texts.

At the same time, postcolonial nations like Canada or Australia present a more complex constellation when it comes to the politics of cartography. The majority population may find itself in a critical position vis-á-vis colonial understandings of space and, simultaneously, in a position of colonial continuity. Here, the role of cartography

cannot be solely envisaged as the reworking of a particular spatial paradigm, but consists rather in the implementation of a series of creative revisions which register the transition from a colonial framework within which the writer is compelled to recreate and reflect upon the restrictions of colonial space to a postcolonial one within which he or she acquires the freedom to engage in a series of ‘territorial disputes’ that implicitly or explicitly acknowledge the relativity of modes of spatial (and by extension, cultural) perception. (Huggan 2008, 30)

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

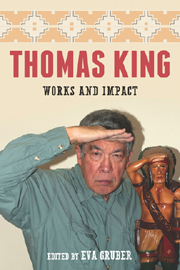

- Thomas KingWorks and Impact, pp. 210 - 223Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2012