In the early modern era, millions of people were enslaved, dispossessed, and forcibly displaced from sites in West Africa and West-Central Africa to European imperial realms where the meanings of slavery and freedom were codified into distinct rules of law. These laws and traditions often differed from legal cultures about slavery in enslaved peoples’ places of origin or the sites where they or their ancestors were first enslaved. Slavery and Freedom in Black Thought traces how West Africans and West-Central Africans and their descendants reckoned with the violent world of Atlantic slavery that they were forced to inhabit, and traces how they conceptualized two strands of political and legal thought – freedom and slavery – in the early Spanish empire. In their daily lives, Black Africans and their descendants grappled with laws and theological discourses that legitimized the enslavement of Black people in the early modern Atlantic world and the varied meanings of freedom across legal jurisdictions. They discussed ideas about slavery and freedom with Black kin, friends, and associates in the sites where they lived and across vast distances, generating thick spheres of communication in the early modern Atlantic world. Discussions about freedom and its varied meanings moved from place to place through diverse exchanges of information, fractured memories, and knowledge between Black communities and kin across the Atlantic Ocean.

Slavery and freedom were two concepts and legal categories that regulated the lives of every person of African descent in continental Europe and in the Americas in the early modern era. European empire-building projects in the Americas from the sixteenth century onwards and ambitious plans to extract and exploit the region’s natural resources led to insatiable demand for unfree labor to sustain these projects. In response, European traders and colonists created intense demand for the enslavement, dispossession, and forcible displacement of people from West Africa and West-Central Africa.Footnote 1 Armed with slave-trading licenses granted by the crowns of Spain, Portugal, England, France, and other European kingdoms (and, later, nations), merchants, investors, and ship captains who operated in sixteenth-century West Africa and West-Central Africa attempted to transform people into commodities, who they would later trade as inanimate property. This acute European demand for enslaved labor displaced over 12.5 million people from their kin and homelands over the course of three centuries, barring them from property ownership and free will, and causing cycles of devastating warfare and displacement across West African and West-Central African polities and kingdoms.Footnote 2 European merchants and slave-ship captains subjected their victims to grueling and violent crossings of the vast Atlantic, a voyage known contemporaneously as the Middle Passage.Footnote 3 Ship captains presided over such dangerous, violent, and cramped conditions on their ships that the mortality rate among enslaved people on these crossings was approximately 20 percent prior to 1600.Footnote 4 When slave ships arrived in the Americas, merchants sought to trade their enslaved embargo in the marketplaces of emerging slave societies on the continent. In doing so, they condemned those who survived the horrors of the Middle Passage to a life of harsh and dangerous unfree labor in slave societies where their enslavement was codified in laws (especially in the Spanish and Portuguese monarchies), and where the emergence of racial thinking tended to equate people who were racialized as Black as slaves or enslaveable.Footnote 5 In this violent early modern Atlantic world, European legal codes and prevalent attitudes of intolerance towards people racialized as Black rendered the lives of Africans and their descendants as highly vulnerable to unquantifiable harm, trauma, and violence. In this context, it is no surprise that enslaved and freeborn Black people sought to grapple with the diverse juridical meanings and rules of law concerning slavery and freedom in European empires, and understand how these differed from those in their places of origin in West Africa and West-Central Africa.

Freedom was often the most important concept that governed the preoccupations and day-to-day lives of enslaved, liberated, and freeborn people who were racialized as Black in the early modern Atlantic world. Some sought freedom from slavery on their own terms through precarious flights from enslavement and the establishment of self-governing communities, often known as palenques.Footnote 6 Fugitives from slavery built palenque communities across the sixteenth-century Spanish Americas (and in the broader Atlantic world), particularly in the Spanish Caribbean. The Spanish crown often waged war against such communities, perceiving their establishment as an act of aggression, while occasionally negotiating peace when politically expedient. Black people discussed freedom across legal jurisdictions too, as enslaved people learned about laws of slavery and freedom in other imperial realms where they might be able to obtain freedom or live with greater degrees of liberty within enslavement. One example is how enslaved Black people in late seventeenth-century British Jamaica and other Caribbean sites sometimes fled plantation slavery by aiming for Spanish territories where they understood slavery and freedom as being distinct legal categories in Castilian law that might improve their precarious lived experiences. For example, after the Spanish crown introduced sanctuary policies in the 1680s, enslaved people in English and French imperial realms soon learned that they could claim liberty under Spanish law if they touched foot in Spanish territories, and they shared this precious information with other enslaved people to encourage them to join the flight.Footnote 7 Other enslaved Black people in the Spanish empire navigated diverse legal ecologies of freedom by litigating for their entire or partial freedom in royal, ecclesiastical, and inquisitorial courts, while sharing the broad aim of pressing for a freedom (or fraction of freedom) that was codified in law and could be proven through official paperwork issued by a court.Footnote 8 Whatever means Black people deployed to seek degrees of freedom in their lives, discussions about freedom and its varied meanings moved across the Atlantic world.

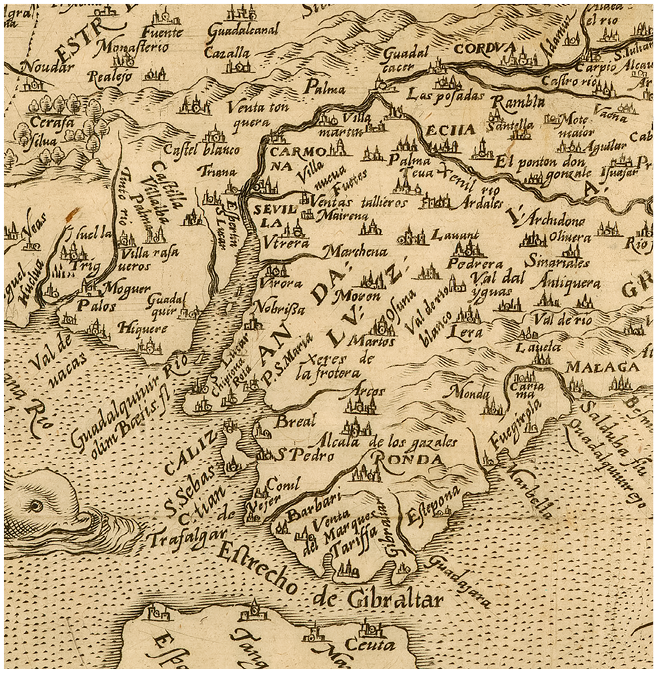

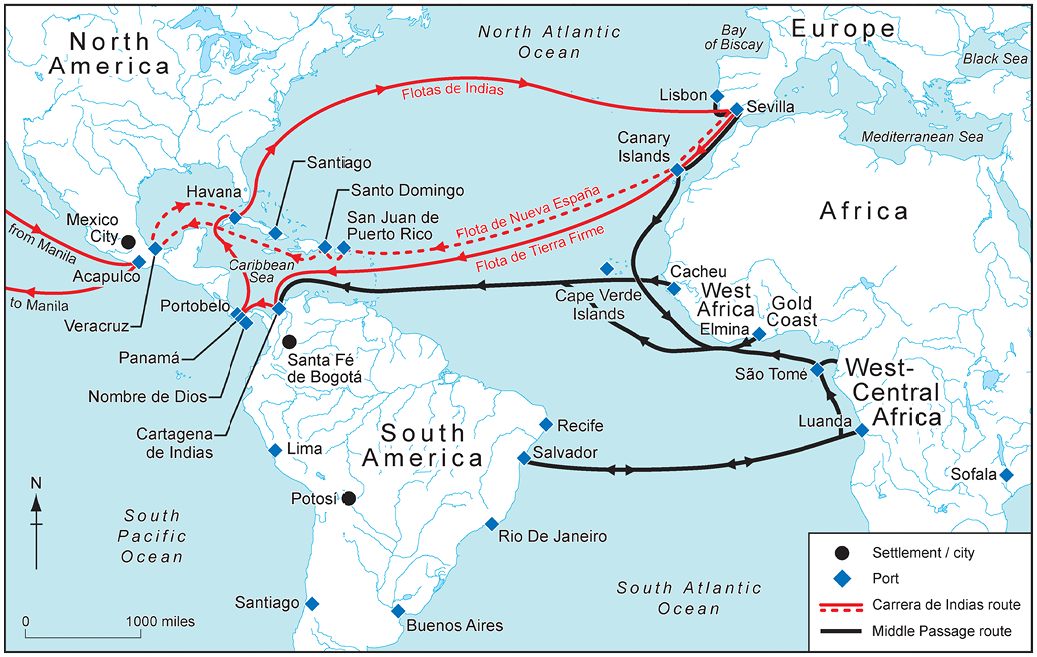

Slavery and Freedom in Black Thought traces how Black communities and kin exchanged ideas about slavery and freedom across the long sixteenth century (1520–1630) in the Spanish Atlantic world. The book sketches the emergence of thick spheres of communication among free and enslaved Black people between key port towns through relays of word of mouth, epistolary networks, and legal powers. In particular, everyday lives and experiences in the ports that constituted the maritime trading routes in the late sixteenth-century Spanish Atlantic (known as the Carrera de Indias), namely Cartagena de Indias, Havana, Nombre de Dios (and later Portobelo), Sevilla, and Veracruz, and the towns dotted along trading routes between key ports and the viceregal capitals, especially Lima and Mexico City (the capitals of the viceroyalties of Peru and New Spain, respectively), were often intertwined with events across the Atlantic, as ship passengers and port-dwellers trafficked in mundane and noteworthy information about people and events in faraway places (Figure 1.1). Slavery and Freedom in Black Thought explores how relays of word of mouth – stitched together through itinerant merchant communities, mariners, and passengers – bridged vast distances across the Spanish empire and allowed Black dwellers to send and receive messages from kin and associates from afar. Tapping official and informal messengers also allowed Black people to partake in a lettered world of communication by sending and receiving missives that traveled across the Atlantic. Rare surviving letters penned by enslaved Black people to their distant kin also reveal conversations about their hopes and expectations of freedom.

Figure 1.1 Abraham Ortelius, “Regni Hispaniae post omnium editiones locumplessima Descriptio” (detail of “Guadalquivir River [printed in illustration as Guadalquivir Rio] to Sevilla”). In Hispaniae illustratæ seu Rerum vrbiumq. Hispaniæ, Lusitaniæ, Æthiopiæ et Indiæ scriptores varii. Partim editi nunc primum, partim aucti atque emendati. Francofurti: Apud Claudium Marnium, & Hæredes Iohannis Aubrij, 1603.

Slavery and Freedom in Black Thought argues that these vast spheres of communication shaped Black individuals’ and communities’ legal consciousness about the laws of slavery and freedom in the early Spanish empire. This builds on foundational work by scholars who have explored the emergence of a Black legal consciousness in colonial Latin America, as well as scholarship that has explored how Indigenous Americans developed knowledge of plural legal jurisdictions and petitioning in the Spanish and Portuguese empires.Footnote 9 For example, Alejandro de la Fuente has posited that scholars working on the history of slavery should acknowledge that it was not laws that had a social agency, but instead that enslaved people gave meaning to laws through their work as litigants.Footnote 10 Herman L. Bennett has also explored how free Black people residing in New Spain developed a creole legal consciousness and an understanding of how to navigate legal structures. With a focus on the eighteenth century, Bianca Premo has explored how Indigenous Americans, enslaved Africans, and colonial women pressed for royal justice in colonial courts and composed legal arguments about the secularization of law, formalism, rights, freedom, and historicism, and conceptualized ideas in their legal arguments that scholars often associate with a lettered European Enlightenment.Footnote 11 Michelle A. McKinley has studied how enslaved Black women sought to negotiate fractions of their freedom within enslavement in ecclesiastical courts in seventeenth-century Lima.Footnote 12 Similarly, Adriana Chira has explored how Afro-descendants in nineteenth-century Cuba engaged with colonial legal frameworks that allowed custom and manumission in order to gradually wear down the institution of slavery through litigation, self-purchase, and the collection of fragmentary legal papers.Footnote 13

Slavery and Freedom in Black Thought reveals how the speed of communication flows across the late sixteenth-century Spanish Atlantic shaped the lives, ideas, and legal consciousness of enslaved and free Black people who lived in key trading entrepôts. The intensity and fast pace of maritime communication between key port towns in this period meant that news in Sevilla about an enslaved person’s litigation for freedom against their owner in a royal court, or of how an owner had sold one of their domestic slaves and displaced them from Sevilla, or news about an enslaved person’s liberation from slavery may have reached friends and acquaintances in the ports of Veracruz or Cartagena de Indias more quickly than the same news traveled to kin living in other parts of Castilla. For instance, enslaved and free Black residents of late sixteenth-century Sevilla could send a letter or a message through word of mouth to an associate or kin in the Spanish Caribbean and reasonably expect a response with the arrival of the fleet the following year.Footnote 14 This constant movement of people, information, and news about freedom in particular sites served as crucial infrastructure for certain Black individuals and communities to exchange ideas about the laws and customs of slavery and freedom. Partaking in these flows of communication allowed free and enslaved Black people to gather requisite information, knowledge, and strategies to seek or defend their own freedom before royal courts dotted across Spanish imperial realms.

These spheres of communication also shaped the legal consciousness and political strategies of Black religious brotherhoods and confraternities on both sides of the Atlantic. This book is influenced by recent historiographical debates about the applicability of the concept of the “public sphere” to contexts beyond a European lettered and “enlightened” elite, and works that have explored how enslaved and free Black people’s movement across spaces (both voluntary and involuntary) led to the emergence of new forms of knowledge, including ideas about subjecthood, medicine and healing, and Black Catholicism.Footnote 15 For example, it traces how Black confraternities sometimes maintained contact with Black brotherhoods in other sites and shared legal strategies. Take the case of the leader of a prominent Black confraternity in late sixteenth-century Lima, Francisco de Gamarra, who formerly resided in Sevilla where he had been enslaved.Footnote 16 Upon his liberation from slavery, he crossed the Atlantic and settled in Lima where he became a sought-after builder (albañil). In Lima, Gamarra drew on a lifetime of experiences and memories from Sevilla as well as his ongoing ties to the city, especially as his enslaved daughter languished there while he sought to raise funds to pay for the price of her liberty and her voyage to Lima.Footnote 17 Similarly, leaders of Black religious brotherhoods in Mexico City and Sevilla in the early seventeenth century likely communicated with each other in the aftermath of severe political persecution and repression that was instigated by religious and royal authorities in their respective cities. This book traces their strategies for royal justice and the locations from where they organized their petitions, and suggests that the leaders of the Black brotherhoods in Sevilla and Mexico City likely communicated and shared political strategies to build their legal petitions to press for royal justice.

Slavery and Freedom in Black Thought also analyzes how free and enslaved Black people attempted in their daily lives to forge a sense of belonging in an empire that was hostile to them. Existing scholarship has explored how enslaved and free Black people sought to build political ideas of belonging in the Spanish Americas through clothing, economic activities, property ownership, and participation in festive rituals and Black confraternity life.Footnote 18 Slavery and Freedom in Black Thought builds on these studies by exploring how Black people attempted to forge belonging through their participation in colonial bureaucracy (and especially in the creation of paperwork) to build evidentiary thresholds that would improve or defend their legal status.Footnote 19 In particular, the study traces how enslaved and free Black people understood that ideas and practices of belonging in the Spanish empire were often determined by an individual’s local ties, namely the ability to command credible witness testimonies within a community, and the resources to document ties and biographies through paperwork, often before a public notary that would result in a legally binding notarial document known as an escritura.Footnote 20 They learned how to access royal justice and engage in royal petitioning, and understood the significance of gathering relevant paperwork and creating community ties to build evidentiary thresholds in legal spheres. They participated in legal cultures of belonging by enlisting diverse witnesses to testify about their biographies, including friars, friends, former owners, neighbors, merchants, members of the nobility, messengers, priests, servants, slaves, tradespeople, treasurers, and officials in city governance. Those who lacked community ties invested copious resources in generating supplementary paperwork to prove their belonging, in particular to protect and duplicate their freedom papers.

Freeborn and liberated Black people also forged belonging in the Spanish empire by defining and expanding the privileges and rights of freedom. They did so through their day-to-day lives across different sites in the Spanish Atlantic, including their participation in economic life and commerce, labor, property ownership, litigation in royal and ecclesiastical courts, applications for royal licenses to cross the Atlantic as passengers on ships, and petitions to the crown for royal justice in response to local authorities’ attempts to limit the inclusion of free Black men and women in society. Freeborn and liberated Black people also negotiated the meanings of freedom through carefully crafted petitions to the crown requesting justice or grace (privileges) for themselves or their communities. In their petitions, they often envisioned the meanings of freedom and belonging in the Spanish empire in expansive terms. These free Black political actors deftly negotiated various, and often overlapping, legal jurisdictions, and deployed political discourses of belonging to broaden the meanings of Black freedom in the Spanish empire.

As enslaved and free Black people conceptualized and pressed the crown to broaden the meanings and privileges of freedom through their daily practices and petitions in courts, they sought to shape an Iberian rule of law and Catholic tradition that would include Black people in society. An apt example of this discourse of belonging emerges from the defense presented by a Black confraternity in early seventeenth-century Sevilla, in which the Black brothers rejected their proposed exclusion from public religious life in the city by arguing that “Christ put himself on the Cross for everyone, and our Mother of the Church does not exclude us, and she adored us, and many other things more than white people, for we proceed from gentiles and Old Christians, and Black people are not excluded from priesthood as there are today many Black priests and prebendaries in our Spain.”Footnote 21 The intellectual work in this line of defense, and among those deployed by many others who petitioned the crown in this period, sought to reject Iberian ideas that coalesced in the late sixteenth century that regarded Black people’s purity of blood as permanently tainted by slavery and as irredeemably stained, thereby preventing their full inclusion into the Iberian community of Old Christians (a term used for people who could claim at least four generations of Christianity in their family).Footnote 22 In other words, their intellectual work to define the meanings of slavery and freedom in the early Atlantic world rejected ideas about blood lineage that sought to exclude Black Africans and their descendants from Iberian societies and render all Black people as slaves and enslaveable. Instead, through their petitions to the crown, free Black people attempted to expand the meanings of political belonging in the Spanish empire to be inclusive of free Black people. Black people’s intellectual work around political belonging in the Spanish empire had profound implications for the history of ideas about race, Blackness, exclusion, and inclusion in the Spanish Atlantic world, and the meanings and legal customs of slavery and freedom.

From Archival Absences to Kaleidoscopic Archives of Excess: Methodological Reflections on Intellectual Histories of the Black Atlantic

This study of how enslaved, liberated, and free Black people reckoned with the legal meanings of slavery and freedom builds on foundational scholarship in African American intellectual history and the long Black intellectual tradition that has sought to broaden the definitions of intellectual work, in particular, by positioning enslaved and free Black people as intellectual actors in the early modern Atlantic world.Footnote 23 For example, the notion of reckoning deployed in this book builds on Jennifer Morgan’s landmark Reckoning with Slavery.Footnote 24 Morgan traced how enslaved Black women understood economic value during the violent commodification of their own bodies, and how they assessed and measured economic value in their day-to-day lives and decisions. Slavery and Freedom in Black Thought positions enslaved and free Black men and women as intellectual actors, while deploying the notion of “reckoning” to study how people conceptualized juridical concepts of slavery and freedom and the diverse ways in which they plotted potential paths towards obtaining their liberation from enslavement and protecting their liberty. This history of ideas about slavery and freedom also builds on scholarship in other traditions, especially Indigenous studies, subaltern studies, and postcolonial studies, that have sought to broaden the meanings of intellectual work beyond a focus on those who put pen to paper, especially historians who deploy an entangled lens to explore the roles of Indigenous actors as producers of knowledge and technology.Footnote 25

The existence of spheres of communication between Black communities across the Atlantic world has been invisible in most historical accounts of the era owing to the various methodological challenges that arise when researching these histories in archives. With a few notable exceptions of lettered Black men in the early Iberian world who penned and published texts, the histories of monarchs and political leaders in West Africa and West-Central Africa who exchanged diplomatic correspondence with Iberian monarchs, and Black Catholic holy people in the Atlantic world whose words were recorded by their confessors, the vast majority of the history of Black thought in early modern Europe is etched into the historical record through archival fragments within documents produced by institutions of colonial administration and justice, or ecclesiastical and religious courts, all of which tended to be hostile towards enslaved and free Black people.Footnote 26 Yet scholarship that has explored how West African and West-Central African cultural and political ideas, practices, and legacies survived in the Americas despite the violence of enslavement, forced displacement, and dispossession in the Atlantic world offer important examples for broadening historical methodologies to confront the challenges of archival absences.Footnote 27

The methodological work in this study also emerges in dialogue with scholars working within Black feminist traditions who have developed foundational methods to read and grapple with the archival silences and the violent erasures of the private and intellectual lives of enslaved and free Black women from the historical record.Footnote 28 In particular, Saidiya Hartman has paved an important path by coining “critical fabulation” as a historical method that pieces together the possible experiences of people whose lives were etched in the archive through violence or who were absent and dispossessed in the historical record.Footnote 29 Marisa Fuentes has also developed methodologies to respond to the absence of enslaved Black women’s voices in historical archives of late eighteenth-century Barbados.Footnote 30 Fuentes deploys the tools of critical fabulation, reasonable speculation, and reading along the bias grain within “a microhistory of urban Caribbean slavery” that explores enslaved Black women’s lives through the urban geographies and environments where they lived.Footnote 31 With a more expansive geographical frame, Jessica Marie Johnson has asked us to consider the possibilities of writing histories of Black women’s practices of freedom in their intimate spaces across the Atlantic world through an “accountable historical practice that challenges the known and unknowable, particularly when attending to the lives of black women and girls.”Footnote 32 Johnson assembled diverse historical fragments of daily life across vast spaces of the French Atlantic, namely Senegambia, the Middle Passage, and New Orleans, and reads these fragments alongside each other, noting how “although it is critical to respect the limits of each document, by bringing material together in careful and creative ways, snippets of black women’s lives begin to unfold.”Footnote 33 Finally, in Reckoning with Slavery, Jennifer Morgan explores the coherence between ideas about economic value and race in order to unearth the “lived experiences and analytic responses to enslavement of these whose lives have most regularly and consistently fallen outside the purview of the archive.”Footnote 34 Collectively, this scholarship invites us to consider silences in the archive as crucial pieces of historical evidence about enslaved Black women’s lives, and to deploy an array of research methods to reimagine the possible experiences and ideas of enslaved women.

Inspired by these methodological discussions about archival absences and tasked with a separate challenge of writing a history of ephemeral conversations and exchanges of ideas about slavery and freedom between Black kin, friends, and associates across the sixteenth-century Spanish Atlantic, I began to assemble thousands of fragmentary testimonies about Black life and ideas across four urban sites in the Spanish Atlantic. These sites include the ports of Cartagena de Indias, Nombre de Dios, Sevilla, and Veracruz, and their respective hinterlands, over the long sixteenth century. The book assembles these fragments of historical evidence about Black life and thought to create a deliberate sense of kaleidoscopic archival excess that occasionally reveals aspects of the history of Black people’s ideas about slavery and freedom. The study layers these kaleidoscopic strands of archival excess into discrete spatial frames of analysis, such as life and gossip among neighbors in a compact parish in a city, everyday life and legal knowledge in towns along a key trading route in an American colony, or the conversations between an enslaved man with strangers during multiple forced displacements across the Atlantic while he was trying to gather enough legal knowledge to launch an appeal against his illegitimate enslavement, or when assessing the significance of the employment of free and liberated Black men as town criers to convey news and to administer public auctions of enslaved people. Each of these spatial frames relies on a diverse methodological toolset, for example, drawing inspiration from foundational works in microhistory, cultural history, and histories of ideas and intellectual history.

The methodological work in this study is also shaped by spatial turns in the history of ideas, cultural history, and historical geography. In particular, my conceptualization of public spaces as key sites for exchanges of ideas has been influenced by reading scholars of Arab intellectual history who pinpoint the movement of people across and between political spaces and public sites as important components for the exchange and disputation of ideas.Footnote 35 For example, Muhsin J. Al-Musawi argued that historians must consider an active sphere of discussion and disputation within the history of ideas, arguing that “the ‘street,’ as opposed to scholars and other elites, has always been part of its own opposite poetics or discourse, while in other instances its case may be played out against innovations in theological discussion.”Footnote 36 Scholars working in historical geography of Black life in the colonial Americas have also developed methodologies to explore how environmental elements shaped Black life and society.Footnote 37 These readings helped me to visualize the spaces where enslaved and free Black people might have exchanged ideas in the early Atlantic world, whether exploring conversations playing out across the Atlantic on fleets crisscrossing the ocean, in port cities of the Caribbean, on street corners and squares of bustling cities, at inns and canteens along key trading routes, through relays of word of mouth among travelers in port towns, in church congregations, in markets, or in other spaces where meetings and conversations emerged amid the bustle of daily life. My approach to the orality of these diverse histories of ideas about slavery and freedom also reflects the influence of historians working on the history of communication in cities in the early modern period, such as John Paul Ghobrial, Giuseppe Marcocci, Christian de Vito, and Felipo de Vivo, who have played with scales of analysis to write histories of news in the everyday life of early modern cities, revealing urban landscapes and diverse soundscapes as key pieces of historical evidence.Footnote 38 Nicholas R. Jones has also invited us to consider how theatrical stages in this era might mirror the soundscape of cities, particularly the vernacular language and accents of different imperial subjects that a playwright might mimic in scripts and stage directions.Footnote 39 Finally, works in historical geography have also visualized how ideas moved and were exchanged across various sites. For example, in a study of slave revolts in eighteenth-century Jamaica, Vincent Brown maps the history of Black political thought about slavery and rebellion onto diverse geographical terrains and traces how these ideas were exchanged among enslaved laborers toiling on plantations as well as dwellers in towns.Footnote 40

Thinking spatially about the history of ideas also requires us to consider whether the history of Black thought about slavery and freedom in this period was a uniquely urban phenomenon. Certainly, dwellers of port towns and viceregal capitals of the Atlantic world were often at the forefront of relays of communication, especially those who lived in ports that served as key destinations on maritime or overland trading routes.Footnote 41 In addition, archival evidence tends to be more plentiful in towns and cities as urban dwellers accessed courts of royal and ecclesiastical justice and the services of public notaries more often than their rural counterparts.Footnote 42 However, the greater volume of imprints of urban dwellers’ lives and ideas in historical archives does not mean that the history of slavery and freedom in Black thought was a uniquely urban phenomenon. As Vincent Brown demonstrates in Tacky’s Revolt, ideas about slavery and rebellion among enslaved Black people in eighteenth-century Jamaica spread across rural plantations as well as towns, as enslaved and free people on plantations taught recently arrived enslaved West Africans about the histories of previous revolts on the island. Slavery and Freedom in Black Thought focuses on urban landscapes because this is where a concentration of archival fragments exists to write this history. Yet the study also considers how conversations and ideas about slavery and freedom moved across vast spaces in the Spanish Atlantic world and connected rural and urban populations, as people discussed and debated these ideas with friends, kin, and associates, and plotted their hopes to obtain their liberty or greater degrees of freedom in their lives. Where possible, the book explores particular lives and lived experiences on urban and rural landscapes to make visible the shared spaces where people from different backgrounds converged and shaped one another’s ideas, be it in congregations, as passengers on ships, on street corners, or through word of mouth or hearsay in urban life. The study also explores the significance of travel between places – whether over land or sea – to the history of slavery and freedom in Black thought.

Slavery and Freedom in Black Thought in the Early Spanish Atlantic

This study is an intellectual exploration of the rich, complicated, and worldly lives of people of African descent as they negotiated experiences of enslavement and liberation from slavery in the early modern Spanish empire. Criss-crossing multiple scales of analysis, from micro to macro, from the formal to the intimate, and from individuals’ engagement with institutional processes to their spatial cosmographies, the book charts an intellectual cartography of early modern Black life that upends our understanding of Black movement across spaces, Black intellectual history, and Black agency at the dawn of and decades into the Atlantic trade in enslaved Black people. In disparate, but intimately tied sites in the early Spanish empire (from Sevilla and Mexico City to Nombre de Dios and Lima, among other key ports and towns), West Africans, West-Central Africans, and their descendants not only traveled between such spaces and constructed a Black Iberian world, but actively assembled a dynamic Black public sphere across oceans, seas, and overland trading routes, and offered their own competing intellectual visions of slavery and freedom.

In this shared Black Iberian Atlantic world, the meanings of slavery and freedom were fiercely contested and claimed. Weaving together thousands of archival fragments, the study recreates the worlds and dilemmas of extraordinary individuals and communities while mapping the development of early modern Black thought about slavery and freedom. From a free Black mother’s embarkation license to cross the Atlantic as a passenger on a ship, or an enslaved Sevillian woman’s letters to her freed husband in New Spain, or an enslaved man’s negotiations for credit arrangements with prospective buyers on the auction block in Mexico City, to a Black man’s petition to a royal court in an attempt to reclaim his liberty after his illegitimate enslavement, Africans and their descendants were important intellectual actors in the early modern Atlantic world who reckoned with ideas about slavery and freedom in their daily lives. Their intellectual labor invites us to reimagine the epistemic worlds of the early modern Atlantic. Through fragments of personal letters, depositions in trials, commercial agreements, and petitions to the crown, the study pieces together the lives of Black men and women both in metropolitan Spain and the colonies, how people moved from one place to another, and, more importantly, how ideas and information moved and operated in different contexts. Free and enslaved people who moved freely or by force across the Atlantic shared information and legal knowledge with those they met along the way.

The study is divided into six chapters and a coda. Chapter 1 explores how free and liberated Black individuals responded to institutional processes that increased bureaucratization in the Spanish empire to understand freedom as a legal category that could be proven or unproven through paperwork. Chapter 2 plays with micro and macro scales and a spatial approach to a history of ideas by collating kaleidoscopic fragments about freedom as part of disjointed collective memories and the emotional histories of freedom, tracing how enslaved people held out hope for their liberation from slavery and the myriad ways in which they discussed and plotted for their liberty. Chapter 3 charts an economic history to document how enslaved people fought against all the odds to raise capital to purchase their freedom and the liberty of their loved ones. Chapter 4 explores how free Black people conceptualized freedom politically as they sought to make sense of repression and persecution against free Black people in the Spanish empire. Charting a history of Black petitioning for royal justice, the chapter traces how free Black people and communities across the Spanish Atlantic sought to reshape the political meanings of Black freedom and political belonging in the Spanish empire. Chapter 5 traces how enslaved and free Black people regarded freedom as an item that people possessed and that had to be carefully guarded, for it could be stolen from them. Tracing legal cases in which enslaved people argued that this had occurred, this chapter approaches freedom from a juridical point of view, tracing discussions among enslaved and free people about the laws of slavery and freedom and the strategies they shared about how to retrieve the freedom they had lost. Finally, Chapter 6 explores how free people, especially women, invested copious resources to live and practice freedom in their daily lives so that they could be seen to be living with freedom, namely by becoming active economic actors who judiciously recorded their economic activities and their practices of freedom by engaging in cultures of paperwork. The Coda introduces readers to two rare surviving epistles that constitute the earliest known private letters written by an enslaved Black woman in the Atlantic world. Owing to their immense historical value, these letters are printed in Spanish and English translation. As I have managed to locate the precise location where the author of these letters dwelt in Sevilla, I have drawn a map to visualize her possible social ties among her Black neighbors who were alive in her lifetime (Figures C.1.1–2). Readers will note that I also refer to these letters and Figure C.1.1 throughout earlier chapters in the book.

Figure 1.2 Map of shipping routes in the sixteenth-century Spanish and Portuguese Atlantic world, principally depicting the Spanish crown’s Carrera de Indias routes, including the Flota de la Nueva España and the Flota de Tierra Firme, as well as broadly representing the principal shipping routes of European ships that forcibly displaced enslaved people from West Africa and West-Central Africa to Spanish and Portuguese Americas and Europe (often described as the “Middle Passage”).

Terms and Omissions

The book explores the intellectual legacies of people whom the Spanish monarchy racialized in the sixteenth and seventeenth century as Black. Some of the people studied in this book were born in West Africa or West-Central Africa where they were enslaved and forcibly displaced to Europe or the Americas. Others were born enslaved or free in Castilla or the Americas. The ethnonyms that appear throughout this study represent different political and linguistic communities in West Africa (Bañol, Biafara, Bran, Casanga, Cocoli, Jolofe, Mandinga, Valunka, Yalonga, Zape) and in West-Central Africa (Angola, Congo), but are only a fraction of the ethnonyms used to describe African diasporic peoples in the early modern Atlantic world.Footnote 43 Most often, these ethnonyms appear in historical documents when an enslaved or free person was referred to (or referred to themselves) by a first name followed by an ethnonym that indicated the person’s place of birth or where their parents descended from. As this is not a study of the diverse meanings of ethnonyms and their survival and transformation in the Americas, the ethnonyms are presented in the text with minimal translation or interpretation. Similarly, because this study focuses on ideas about slavery and freedom in Black thought, and not the history of ideas about race in Iberian thought and the diverse and often contested meanings of racial markers and how these meanings varied across different sites, I have also retained the vocabulary of racial markers deployed in the historical documents without translating the varied and often contradictory meanings of these terms.Footnote 44 Instead of offering interpretations of these terms, when scribes, notaries, or enslaved or free people used the terms such as atezado (description of someone as very Black), bozal (often used to indicate an enslaved person who could not speak Spanish), mulata (usually referring to a person of Afro-European heritage), negra (Black), and more ambiguous terms sometimes used to describe people of Black heritage, such as lora and morena, I have used these same terms on the first occasion when introducing the person in the text to indicate to the reader the ways that the person under discussion was being racialized in their own lifetime. In those instances, I have translated negro/negra through the text to the English word, Black, while I have retained the original Spanish terms for atezada, lora, mulata, and morena. In the cases where the same person was referred to with more than one racial marker, or where they themselves used a different term, I have made this difference clear in the text. When I use the term horro or horra it is to signify to the reader that the person under discussion has been liberated from slavery under Castilian laws of slavery within their lifetime in a legal act known as alhorría, and usage of the term usually follows the language of the sources – although sometimes I have added the term to indicate or clarify that the person has been liberated from slavery. When referring to an alhorría that resulted from an enslaved person or a third party furnishing sufficient funds to pay the market price of the enslaved person’s value to an enslaver with the purpose of liberating the enslaved person from slavery, this payment is referred to throughout the text as a rescate, following the legal meaning of the term and common usage across testimonies in the sixteenth century.

Throughout the text, I have also used the terms “Spanish empire,” “imperial context,” “imperial institutions,” and “colonial society,” even though I am aware that contemporaneous political thinkers and the Habsburg crown and its deputies did not define or envision the Spanish Americas as a colony of the crown, but rather as a series of dependent viceroyalties, and nor did they see the crown as an empire.Footnote 45 Nonetheless, for people whose lives were violently ruptured by slavery, dispossession, and physical extraction from their homelands, and who bore generational trauma as they were forced to live in societies where their enslavement was justified and codified in law, the difference between a kingdom composed of viceroyalties or an empire was perhaps irrelevant. Instead, they knew and understood that a conquering state in the name of the Spanish crown had conquered, waged wars, and devastated existing Indigenous societies across the Americas, while participating in and legitimizing – through legal codes and customs – the forced removal of millions of enslaved Africans to fill labor shortages resulting from the crown’s ambition to extract natural resources from the newly conquered lands and build imperial societies. The use of the terms “empire,” “imperial,” and “colonial” are purposeful reminders to the author and the readers of the violence experienced by the subjects of this book, rather than an assessment of the nature of the polity or state in the period under study.

Any frame of analysis inevitably excludes important histories, and this study is no exception. In this book, the focus on African Diasporic people and their ideas across vast spaces in the Spanish Atlantic world in the long sixteenth century excludes the histories of many other people who inhabited these sites and who were engaged in similar reckonings with ideas about slavery and freedom. For example, from the early sixteenth century onwards, hundreds of thousands of Indigenous people were enslaved, dispossessed, and displaced by Spanish colonists. Indigenous communities played a key role in rebelling against their enslavement by Spanish colonists, and in contributing to debates about the illegitimacy of enslaving Indigenous Americans led by Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas (1484–1586). These debates eventually led to the crown’s introduction of the New Laws in 1542, which outlawed the enslavement of Indigenous Americans, with the exception of people captured in a just war.Footnote 46 Similarly, this study also omits the lives and ideas of diverse subaltern people in Castilla who pressed royal courts for the expansion of their rights and privileges.Footnote 47 Such omissions include the vast and important history of non-Christians who were captured in what the Spanish termed as “just wars,” as well as the histories of Jewish and Muslim people whom the Spanish crown expelled from its kingdoms in successive waves of repression and intolerance throughout the late fifteenth and late sixteenth century, as well as the lives of those who agreed to convert to Christianity and remain in Castilla as New Christians, namely conversos (converts from Judaism to Christianity and their descendants) and moriscos (converts from Islam to Christianity and their descendants).Footnote 48

Finally, in a significant, yet inevitable omission, the study does not include any sites in the Lusophone Atlantic world within the key frames of analysis. During the period of this study, the Portuguese crown established colonial entrepôts and settlements in islands near West Africa, including Madeira (1420), the Azores (1439), Cape Verde (1462), and further south along the coastline towards Central Africa, the island of São Tomé (1486), and in mainland West Africa, including in Upper Guinea (Cacheu, 1588) and on the Gold Coast (São Jorge da Mina, in 1482), and later also in West-Central Africa, present-day Angola, including in Luanda (1576) and Benguela (1617). Scholars of slavery in Brazil and West-Central Africa, especially in later periods, have traced the emergence of cultural and political corridors between Brazil and West-Central Africa.Footnote 49 In addition, between 1580 and 1581, the Spanish and Portuguese crowns became unified through the Iberian Union and Philip II of Spain became the ruler of Portugal and the Portuguese empire, an arrangement that lasted until 1640.Footnote 50 The fragmentary archival work undertaken for this project meant it was not feasible to include Spanish and Portuguese cities and their respective rules of law and legal customs in the study. However, Black people who dwelt in Portuguese polities appear throughout the study, often sharing ideas about slavery and freedom that they accrued in each polity.