Book contents

- Second Language Identity

- Second Language Identity

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 On Actors, Architecture, and L2 Advancedness in Higher Education

- Part I Advancedness and the L2 Learner

- Part II Variable Notions of Advancedness

- Part III Assessment, Identity, and Critical Language Awareness As Markers of Advancedness

- Book part

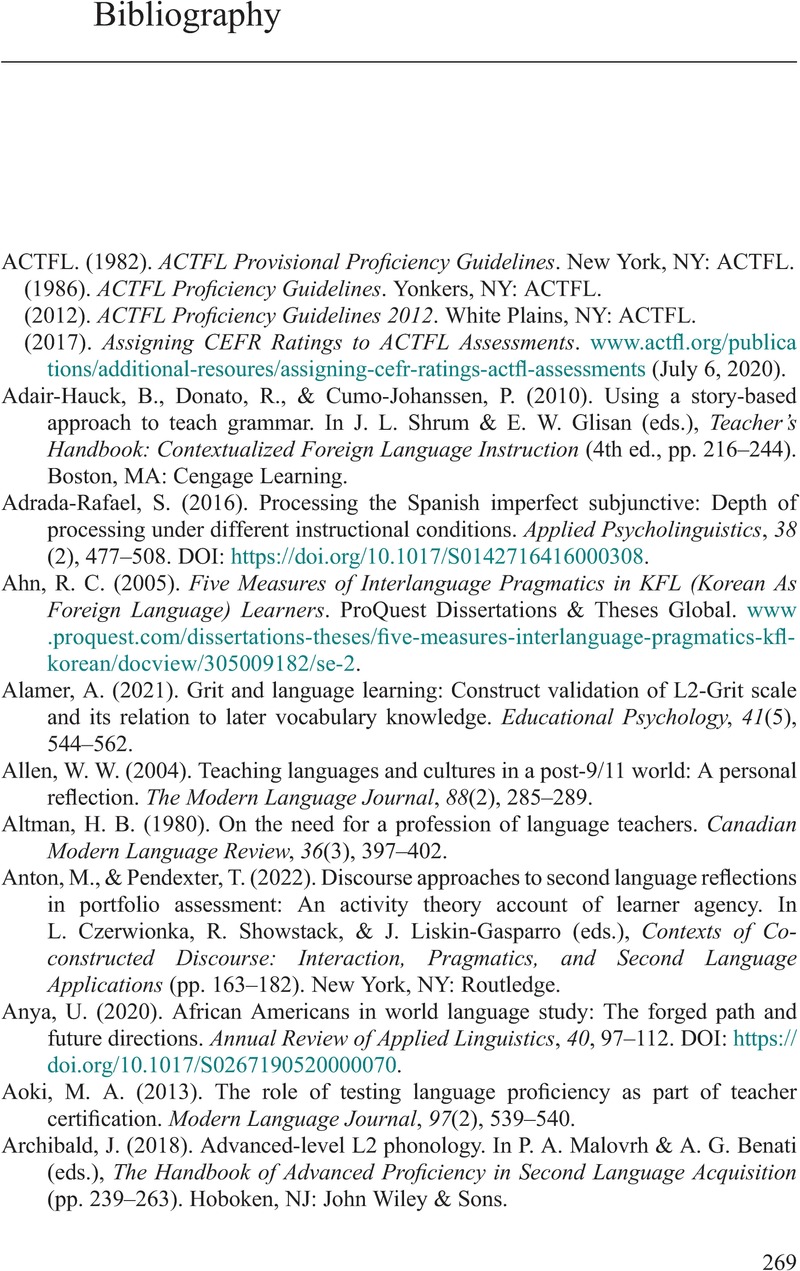

- Bibliography

- Name Index

- Subject Index

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 July 2023

- Second Language Identity

- Second Language Identity

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 On Actors, Architecture, and L2 Advancedness in Higher Education

- Part I Advancedness and the L2 Learner

- Part II Variable Notions of Advancedness

- Part III Assessment, Identity, and Critical Language Awareness As Markers of Advancedness

- Book part

- Bibliography

- Name Index

- Subject Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Second Language IdentityAwareness, Ideology, and Assessment in Higher Education, pp. 269 - 287Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2023