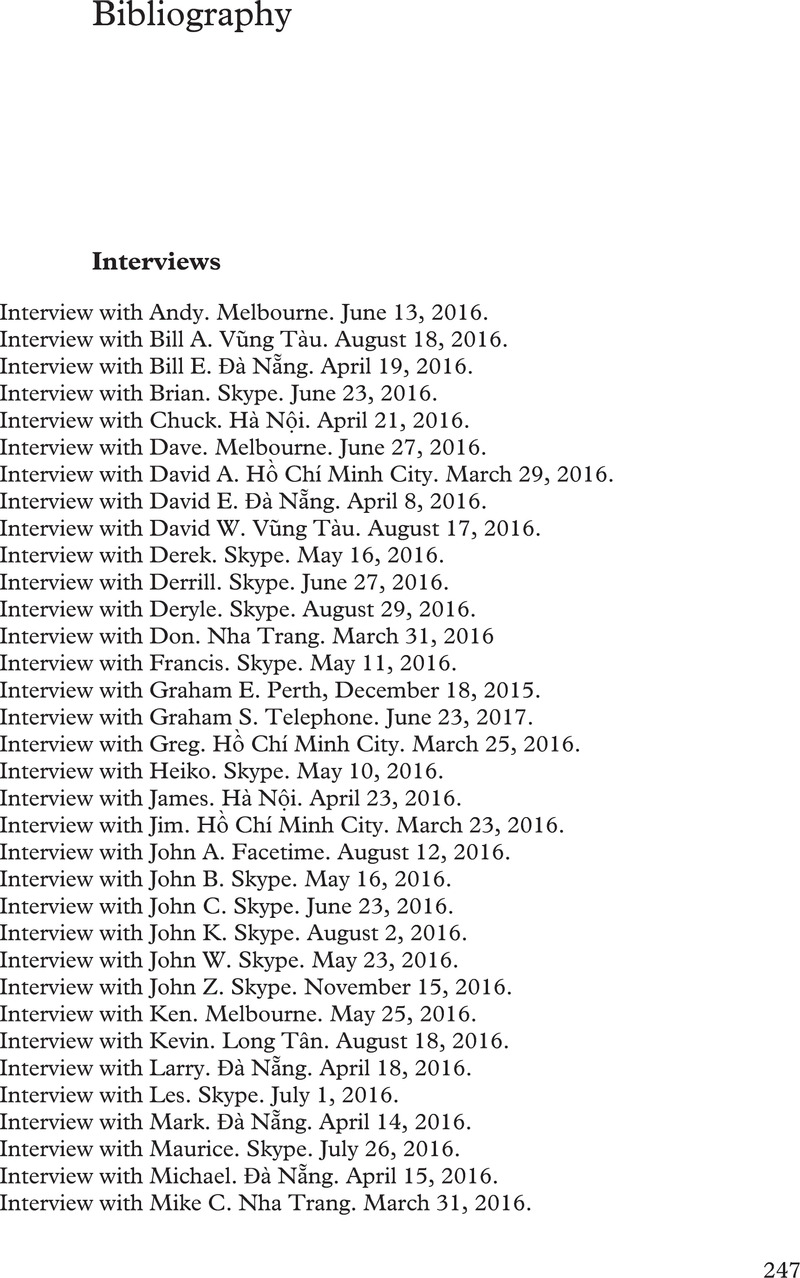

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 October 2021

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Return to VietnamAn Oral History of American and Australian Veterans' Journeys, pp. 247 - 267Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2021