Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Notes on the Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Idealism from Kant to Hegel

- 1 The Unity of Nature and Freedom: Kant's Conception of the System of Philosophy

- 2 Spinozism, Freedom, and Transcendental Dynamics in Kant's Final System of Transcendental Idealism

- 3 Is the Critique of Judgment “Post-Critical”?

- 4 The “I” as Principle of Practical Philosophy

- 5 The Practical Foundation of Philosophy in Kant, Fichte, and After

- 6 From Critique to Metacritique: Fichte's Transformation of Kant's Transcendental Idealism

- 7 Fichte's Alleged Subjective, Psychological, One-Sided Idealism

- 8 The Spirit of the Wissenschaftslehre

- 9 The Beginnings of Schelling's Philosophy of Nature

- 10 The Nature of Subjectivity: The Critical and Systematic Function of Schelling's Philosophy of Nature

- 11 Substance, Causality, and the Question of Method in Hegel's Science of Logic

- 12 Point of View of Man or Knowledge of God: Kant and Hegel on Concept, Judgment, and Reason

- 13 Kant, Hegel, and the Fate of “the” Intuitive Intellect

- 14 Metaphysics and Morality in Kant and Hegel

- Bibliography

- Index

8 - The Spirit of the Wissenschaftslehre

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 03 December 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Notes on the Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Idealism from Kant to Hegel

- 1 The Unity of Nature and Freedom: Kant's Conception of the System of Philosophy

- 2 Spinozism, Freedom, and Transcendental Dynamics in Kant's Final System of Transcendental Idealism

- 3 Is the Critique of Judgment “Post-Critical”?

- 4 The “I” as Principle of Practical Philosophy

- 5 The Practical Foundation of Philosophy in Kant, Fichte, and After

- 6 From Critique to Metacritique: Fichte's Transformation of Kant's Transcendental Idealism

- 7 Fichte's Alleged Subjective, Psychological, One-Sided Idealism

- 8 The Spirit of the Wissenschaftslehre

- 9 The Beginnings of Schelling's Philosophy of Nature

- 10 The Nature of Subjectivity: The Critical and Systematic Function of Schelling's Philosophy of Nature

- 11 Substance, Causality, and the Question of Method in Hegel's Science of Logic

- 12 Point of View of Man or Knowledge of God: Kant and Hegel on Concept, Judgment, and Reason

- 13 Kant, Hegel, and the Fate of “the” Intuitive Intellect

- 14 Metaphysics and Morality in Kant and Hegel

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

“The letter killeth, but the spirit giveth life”

(2 Cor. 3:6)“The letter kills, and this is especially true in the case of the Wissenschaftslehre. Part of the reason for this lies in the nature of this system itself, but part of it may also lie in the particular form taken by the previous ‘letter’ of the same.”

(J. G. Fichte to E. C. Schmidt, 1–6 September, 1798)“Spirit” versus “Letter”

To distinguish the “spirit” from the “letter” of a philosophical text or system is always to ask for trouble, since this distinction can all too easily excuse an indifference to what a particular thinker may actually have said and written and often reveals an attitude of cavalier disregard for questions of documentary evidence. Yet it is equally true that a refusal to rise above the most literal construal of a text can all too easily transform the study of the history of philosophy into a lifeless exercise in “the history of ideas” or reduce it to a branch of philology that remains blithely indifferent to the philosophical issues at stake.

The hermeneutic problem that presents itself here is simply another way of describing the relationship between understanding a portion of a text and the text as a whole. Without an appreciation of the “spirit” of a philosophy or of a philosophical work, one can scarcely understand or appreciate the “letter” of the same, and yet it is equally true that there is, in this case, no path to the spirit except through the letter, just as there is no way to grasp “the whole” except by means of the parts.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

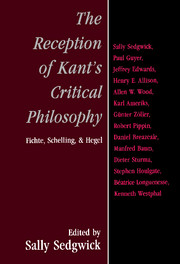

- The Reception of Kant's Critical PhilosophyFichte, Schelling, and Hegel, pp. 171 - 198Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2000

- 4

- Cited by