Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I The Age of Enlightened Rule?

- 1 Women's Political Authority in Maria Antonia Walpurgis von Sachsen's Talestris: Königin der Amazonen (Thalestris: Queen of the Amazons, 1763)

- 2 Maxims of Leadership for a Silent Readership: Sophie von La Roche's Pomona für Teutschlands Töchter and Mein Schreibetisch

- 3 Marcus Aurelius, Also for Girls: Discussions on the Best Form of Government in Enlightenment Hamburg

- 4 Dux Femina Facti: Gender, Sovereignty, and (Women's) Literature in Marie Antonia of Saxony's Thalestris and Charlotte von Stein's Dido

- 5 Crossing the Front Lines: Female Leadership, Politics, and War in Die Familie Seldorf

- 6 Power Struggles between Women in Schiller's and Jelinek's Works

- Part II Leadership as Social Activism around 1900

- Part III Women and Political Power in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries

- Bibliography

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

5 - Crossing the Front Lines: Female Leadership, Politics, and War in Die Familie Seldorf

from Part I - The Age of Enlightened Rule?

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 October 2019

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I The Age of Enlightened Rule?

- 1 Women's Political Authority in Maria Antonia Walpurgis von Sachsen's Talestris: Königin der Amazonen (Thalestris: Queen of the Amazons, 1763)

- 2 Maxims of Leadership for a Silent Readership: Sophie von La Roche's Pomona für Teutschlands Töchter and Mein Schreibetisch

- 3 Marcus Aurelius, Also for Girls: Discussions on the Best Form of Government in Enlightenment Hamburg

- 4 Dux Femina Facti: Gender, Sovereignty, and (Women's) Literature in Marie Antonia of Saxony's Thalestris and Charlotte von Stein's Dido

- 5 Crossing the Front Lines: Female Leadership, Politics, and War in Die Familie Seldorf

- 6 Power Struggles between Women in Schiller's and Jelinek's Works

- Part II Leadership as Social Activism around 1900

- Part III Women and Political Power in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries

- Bibliography

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

Summary

THERESE HUBER'S 1795 novel Die Familie Seldorf has been the subject of much feminist scholarship, with varying results. Elisabeth Krimmer calls the novel “extraordinary” for the ways in which it “foils many of the expectations that we bring to eighteenth-century literature by women writers,” pointing out that “Sara is a positive character in spite of all her violations of the codes of proper femininity.” Stephanie Hilger offers an analysis that reads Sara Seldorf's “mutilated body” as “question[ing] the ideal of wholesome femininity portrayed in bourgeois tragedy and sentimental fiction” and thereby illuminating the failure of the post-Revolutionary body politic to include women. But others see Huber's critiques as insufficient: Inge Stephan argues that the novel fails to challenge prevailing models of femininity, while Wulf Köpke reads Huber as a conservative author. Still others take the ambiguity of Huber's depiction of both femininity and political activity to be typical of the “double-voiced discourse” of women authors around 1800, whose work is marked by “emancipatory elements which coexist with the conventional ones.” These questions become further vexed when one takes into account not only Huber's use of her husband's name to publish her novels (which was not at all unusual for the period) but also her far more conservative and sometimes even misogynistic comments about women writers (in correspondence and in her literary works), the importance of housekeeping, and perhaps especially her remarks about her own mother, whom she excoriated as “gar keine Hausfrau, wir wurden in Schmutz und Unordnung erzogen…. Sie war eine Schwärmerin, war an kein Hausgeschäft gewöhnt, liebte keine weibliche Arbeit” (not at all a housewife, we were brought up in filth and disorder … she was a dreamer, accustomed to absolutely no household duty, loved no feminine work). Even if, as Barbara Becker-Cantarino suggests, this kind of critique is rooted at least partially in Huber's great admiration for her father, the eminent Göttingen professor Christian Gottlob Heyne, it is difficult to square with any notion of Huber as a particularly (proto-)feminist author.

I want to suggest that viewing Die Familie Seldorf in terms of female leadership offers a new way of understanding the work that Huber's novel does without simply falling back on the further contradictions and difficulties of Huber's biography (personal and political).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

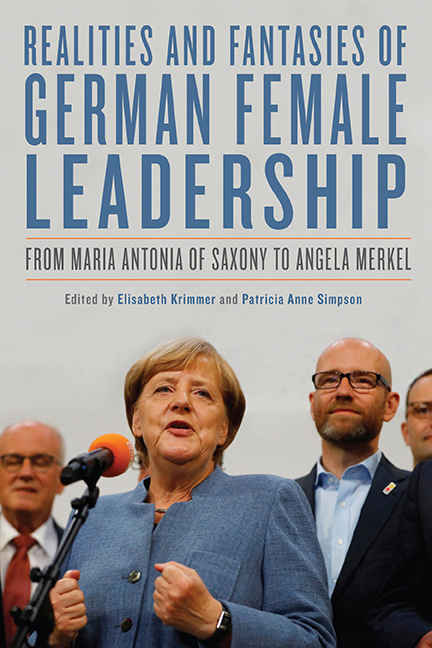

- Realities and Fantasies of German Female LeadershipFrom Maria Antonia of Saxony to Angela Merkel, pp. 113 - 130Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2019