Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Part I Introduction

- Part II Asian primates

- Part III African primates

- 7 Lemurs and tourism in Ranomafana National Park, Madagascar

- 8 Some pathogenic consequences of tourism for nonhuman primates

- 9 Baboon ecotourism in the larger context

- 10 Mountain gorilla tourism as a conservation tool

- 11 Evaluating the effectiveness of chimpanzee tourism

- Part IV Neotropical primates

- Part V Broader issues

- Part VI Conclusion

- Index

- References

9 - Baboon ecotourism in the larger context

from Part III - African primates

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 September 2014

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Part I Introduction

- Part II Asian primates

- Part III African primates

- 7 Lemurs and tourism in Ranomafana National Park, Madagascar

- 8 Some pathogenic consequences of tourism for nonhuman primates

- 9 Baboon ecotourism in the larger context

- 10 Mountain gorilla tourism as a conservation tool

- 11 Evaluating the effectiveness of chimpanzee tourism

- Part IV Neotropical primates

- Part V Broader issues

- Part VI Conclusion

- Index

- References

Summary

Introduction

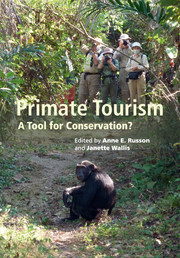

Biodiversity conservation is a growth industry. Controversies abound over approaches and philosophies and about whose rights and whose ethics should apply. In this chapter we address some of these issues based on 38 of our 42 years of experience on the ground, conserving baboons in the face of threats resulting from change in land use, rapid human population growth, escalating rates of poverty, sedentarization of people, and human–baboon conflict – over crops and livestock. One of our strategies has been to promote primate-based tourism. “Walking with Baboons,” our ecotourism product, is distinctly different from other well-known types of primate tourism because it takes place in the arid savannah, in contrast to the more usual forest-based primate tours. The project is located in Kenya which has a well-developed tourism industry with a history of ecotourism among Maasai livestock pastoralists who traditionally were not hostile to baboons.

The baboon ecotourism venture came late in the history of the long-term baboon research. Moreover, it has unique aspects that may not be replicable in other primate settings. Nonetheless, we have been successful in building conservation momentum within the neighboring community. Unintentionally, we expanded and intensified our interactions with it not just around primate-focused tourism but in areas of mutual interest and concern. The process built inter-individual and inter-community bonds which increased the community’s motivation to conserve. We discovered that activities apparently tangential to conservation can make important contributions. This implies that, to succeed as a conservation technique, primate ecotourism needs to be embedded in the larger local social and cultural contexts. This chapter presents the larger context for “Walking with Baboons” as well as the specifics.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Primate TourismA Tool for Conservation?, pp. 155 - 176Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2014

References

- 3

- Cited by