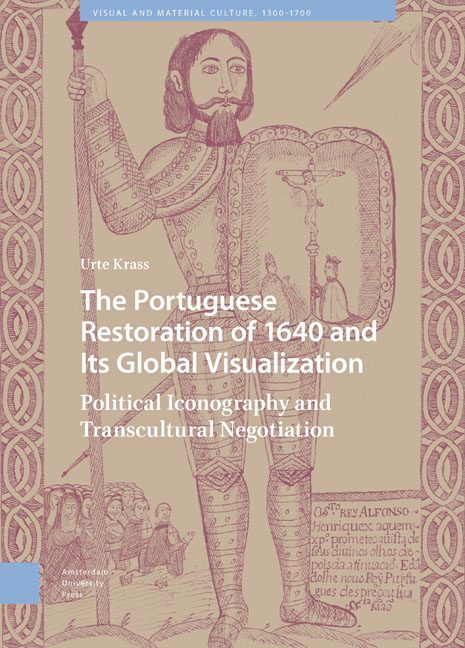

The Portuguese Restoration of 1640 and Its Global Visualization

The Portuguese Restoration of 1640 and Its Global Visualization Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 February 2024

Abstract: It is not only due to the destruction of the city of Lisbon by the earthquake of 1755 that we find hardly any architectural or urban planning traces of the Restoration. Other reasons for this void are the financial strain placed on the new dynasty by the Restoration War as well as the problem that many of the artists and architects who had previously worked in Portugal had become suspect through their cooperation with the Spanish Habsburgs. Furthermore, a conscious decision was made to continue using buildings that had been erected under the Castilian rulers and thus to “rewrite” them. The chapter discusses the difficulties of art patronage for a new dynasty that had to situate itself between tradition and innovation.

Keywords: Lisbon, Restoration monuments, architecture, royal palace chapel, central plan buildings

Breaks and Continuities: The Absence of the Monumental

We learn from Luís de Moura Sobral that in order to legitimize his rule, John IV initiated “an immense propaganda campaign using all available means and media”—an assessment that arguably is somewhat exaggerated. The principle media used were printed texts and images. Much of this material was printed in Paris, or else in London, as was the Lusitania Liberata of 1645, whose engravings rendered it the most ambitious work promulgating the Restoration in iconographical terms. About how the new power structures were visualized in Lisbon, we know relatively little. Has much been lost during the 1755 earthquake and fire of the city? Or can we assume that this branch of the “propaganda campaign” received relatively little attention by the king and his advisors? This is hinted at in a treatise of 1652 entitled Arte de furtar (Art of stealing). In an entirely nonironic way, the text with this great title is dedicated to King John IV and is committed to furthering his memory. The author, presumably the Jesuit Manuel da Costa, recommends that the king, among other things, place statues on Lisbon's rossios and squares. This had, then, apparently not been done twelve years after the revolt. In the years after 1640 hardly any use was in fact made of Lisbon's space to visualize the Restoration. The monument we see today on the Praça dos Restauradores, consisting of an obelisk flanked by the personifications of Independence and Victory, was dedicated in 1886.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle.

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox.

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive.