Chapter 9 - Music and Memory in Mozart’s Zauberflöte

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 January 2021

Summary

As an art working with time and addressing the ear, music, like poetry, requires and challenges memory. As early as the fourth century, Augustine used the example of music to illustrate his meditations on time and memory, describing the process of understanding a melody that unfolds in time, and Edmund Husserl, in his Untersuchungen zur Phänomenologie des inneren Zeitbewußtseins, used music as the most obvious example of how memory and expectation or, in his terminology, retention and protention, cooperate in the perceptive construction of a melody. Perceiving and understanding a melody requires memory, the same kind of short-term memory which is required to understand a sentence. We are dealing here with a form of memory that accompanies and enables cognition, but not ‘remembering’ in the proper sense. Remembering requires a kind of ‘past’ to refer to by an act of remembering. Short-term memory and the interplay of retention and protention have nothing to do with the past, rather, they constitute the present. Music, it is true, has much to do with performing the present as an aesthetic idea and making the present aesthetically sensible. Music is per se an art of memory; it requires memory to be perceived, enjoyed, and understood; it creates and works upon what could be called the memory of an implied listener.

Music draws on two different forms of memory. On the one hand, it employs almost regularly, at least until the twentieth century, certain traditional rhythmic and melodic gestures which are easily identified as allusions to or evocations of certain moods and tempers without functioning as real ‘signifiers’ and may even quote well-known formulae or tunes, or refer to other musical styles or pieces by ways of intertextuality. On the other hand, under certain conditions it may create a ‘past’ and a memory of its own as it unfolds in time. We may call the first form ‘extratextual’ memory, because it refers to elements outside the musical text itself, and the second form ‘intratextual’ memory, since the elements referred to belong to what the listener has already heard within the same piece some minutes ago.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

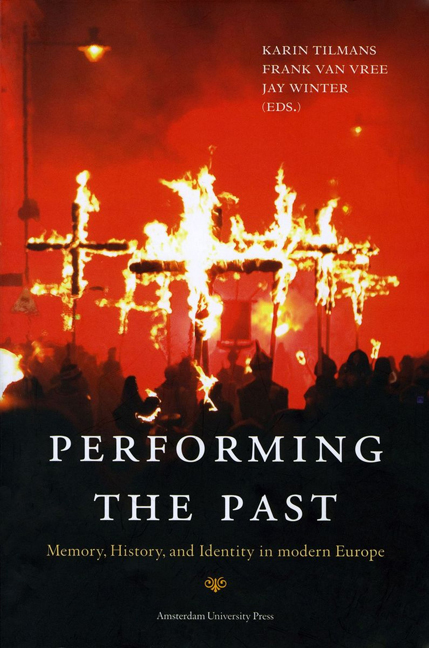

- Performing the PastMemory, History, and Identity in Modern Europe, pp. 187 - 206Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2012